Are you ready for our last letter of the year? We present you with the letter

“R” from Otto Hupp’s “Alphabete und Ornamente” face in the third edition of Alphabets Old and New by Lewis F. Day, 1920. (Typ 1920 .D39. Stone Typography Collection. Image by Petrina Jackson)

R is for the Richmond Theatre Fire

William Dunlap in his A History Of The American Theatre (1832), described the Richmond theatre fire of December 26, 1811:

The house was fuller than on any night of the season. The play was over, and the first act of the pantomime had passed. The second and last had begun. All was yet gayety, all so far had been pleasure, curiosity was yet alive, and further gratification anticipated… when the audience perceived some confusion on the stage, and presently a shower of sparks falling from above… Some one cried out from the stage that there was no danger. Immediately after, Hopkins Robinson ran forward and cried out ‘the house is on fire!’ pointing to the ceiling, where the flames were progressing like wild-fire. In a moment, all was appalling horror and distress.

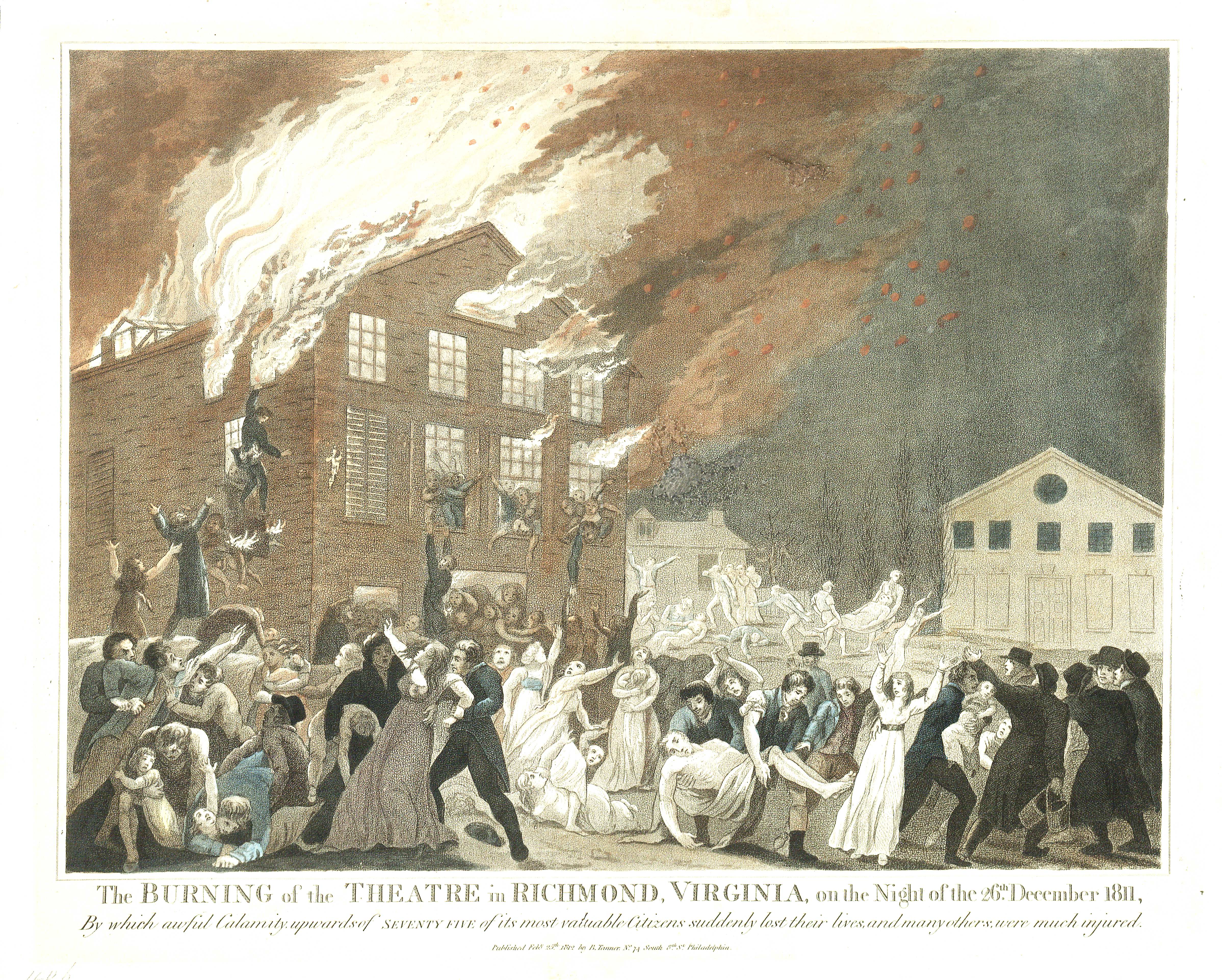

Noted as the worst American urban disaster at the time, the fire was caused by the hoisting of a lit chandelier over the stage which, in turn, set the scenery ablaze. A full house of an estimated 600 spectators scrambled to escape, but 72 playgoers perished including the Governor of Virginia, George William Smith. The Monumental Church was erected on the site of the fire in 1812 as a memorial to those who died.

Contributed by Margaret Hrabe, Reference Coordinator, who is retiring this month. We will miss her!

Lithograph of the Richmond Theatre Fire, undated. (MSS 9408. Merritt T. Cooke Memorial Virginia Print Collection. Image by Petrina Jackson)

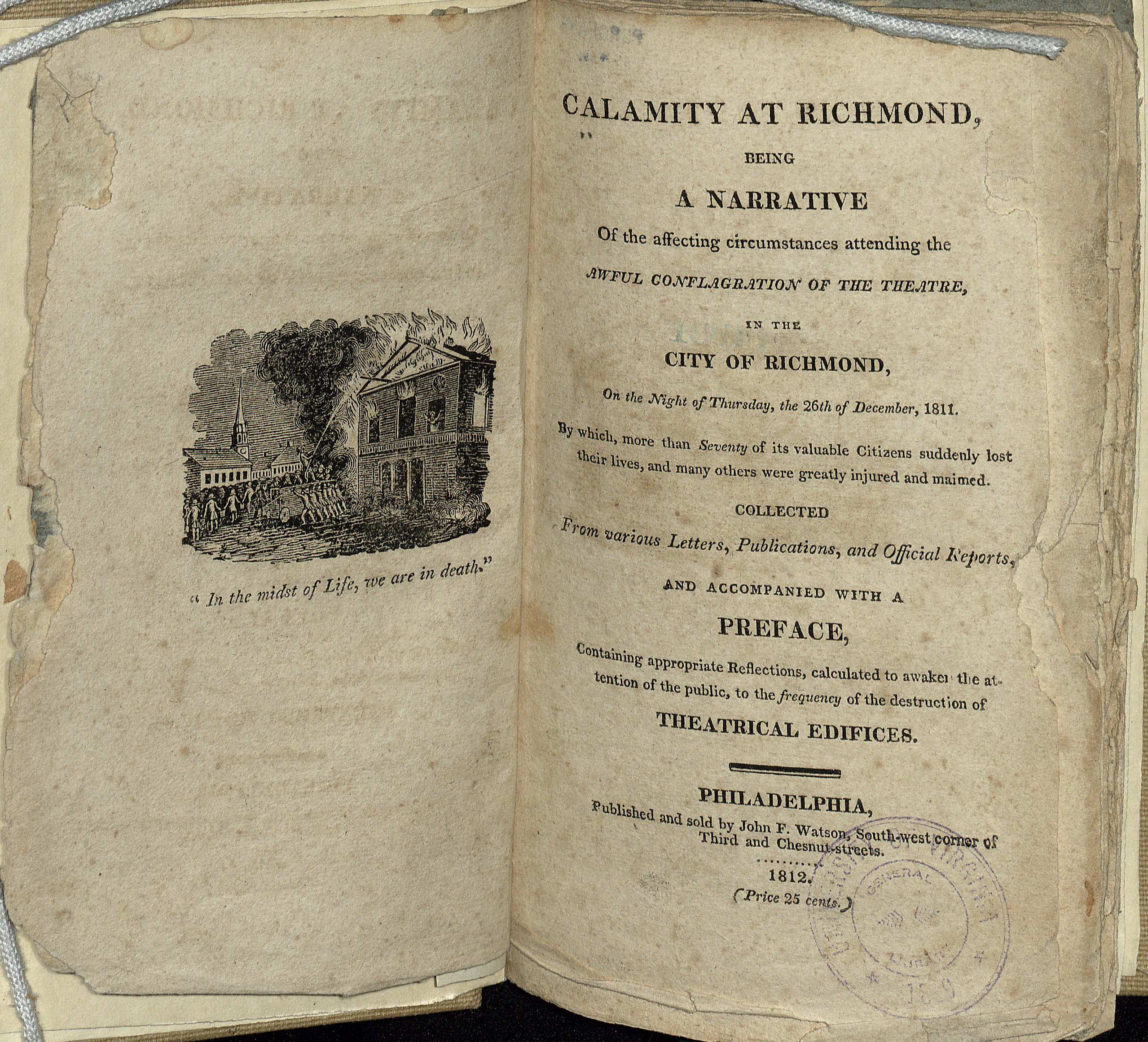

Calamity at Richmond, being a Narrative of the affecting circumstances attending the Awful Conflagration of the Theatre in the City of Richmond, on the Night of Thursday, the 26th of December, 1811. Philadelphia, published and sold by John F. Watson, 1812. (F234 .R5C2 1812. Image by Petrina Jackson)

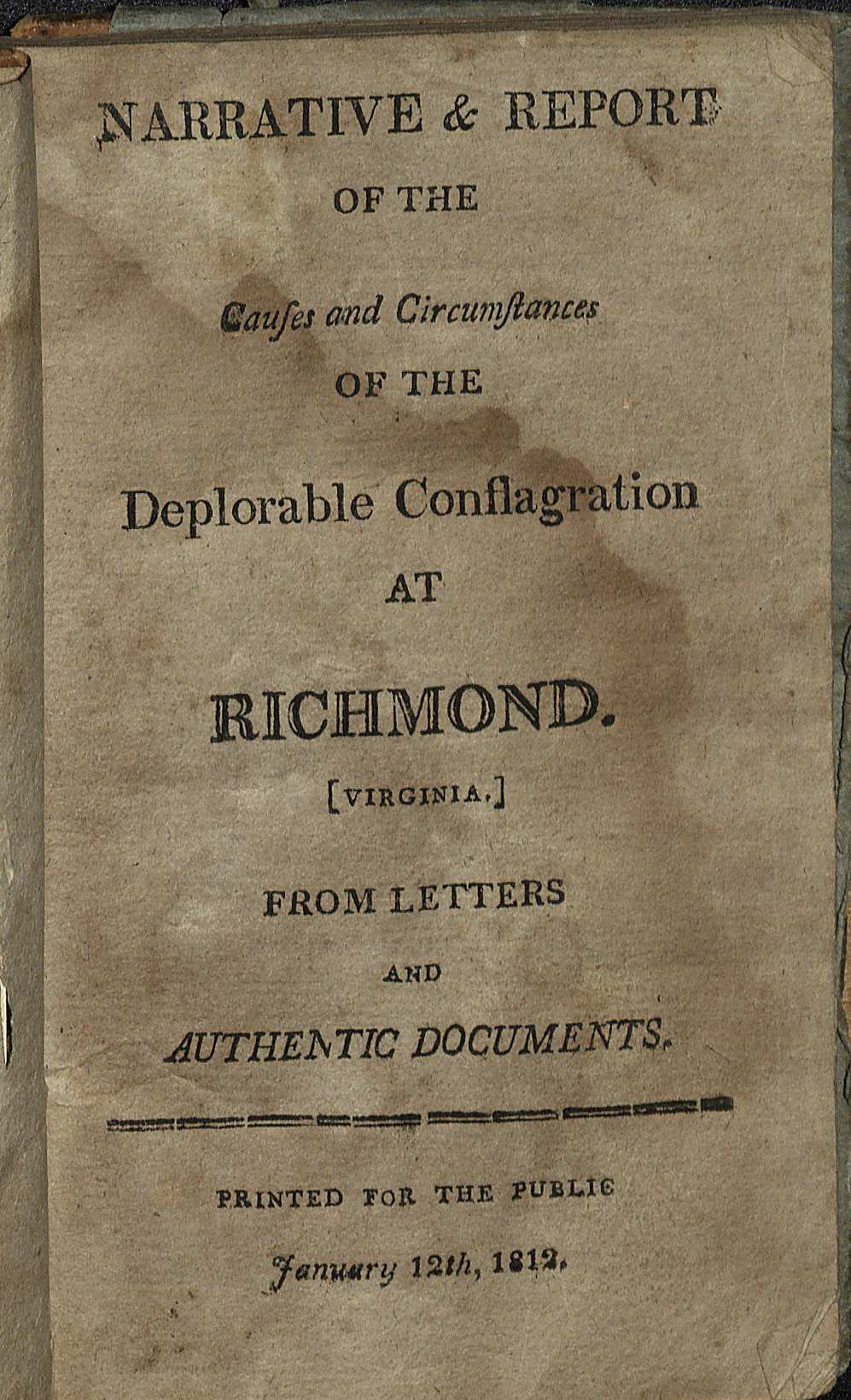

Narrative & Report of the Causes and Circumstances of the Deplorable Conflagration at Richmond. [Virginia.] From Letters and Authentic Documents. Printed for the Public, January 12, 1812. (F234 .R5 N2. Library of Edward L. Stone. Image by Petrina Jackson)

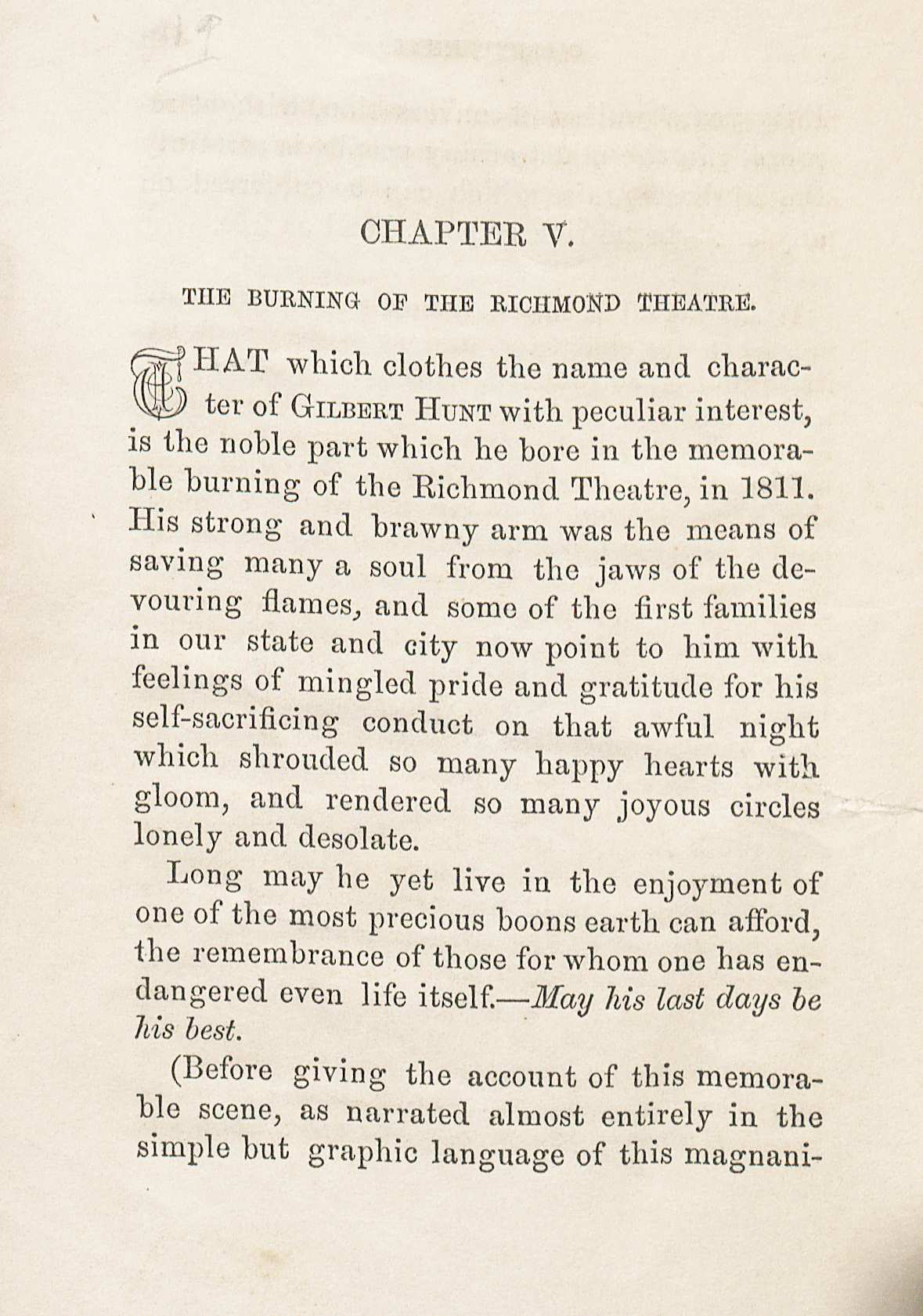

Gilbert Hunt, the City Blacksmith by Philip Barrett. Richmond: James Woodhouse & Co., 1859.

Gilbert Hunt was a freedman who had a blacksmith shop in Richmond and assisted in the rescue and saving of many of the survivors of the fire. (E444 .H9 1859. Image by Petrina Jackson)

Chapter V, “The Burning of the Richmond Theatre” of Gilbert Hunt, The City Blacksmith. (E444 .H9 1859. Image by Petrina Jackson)

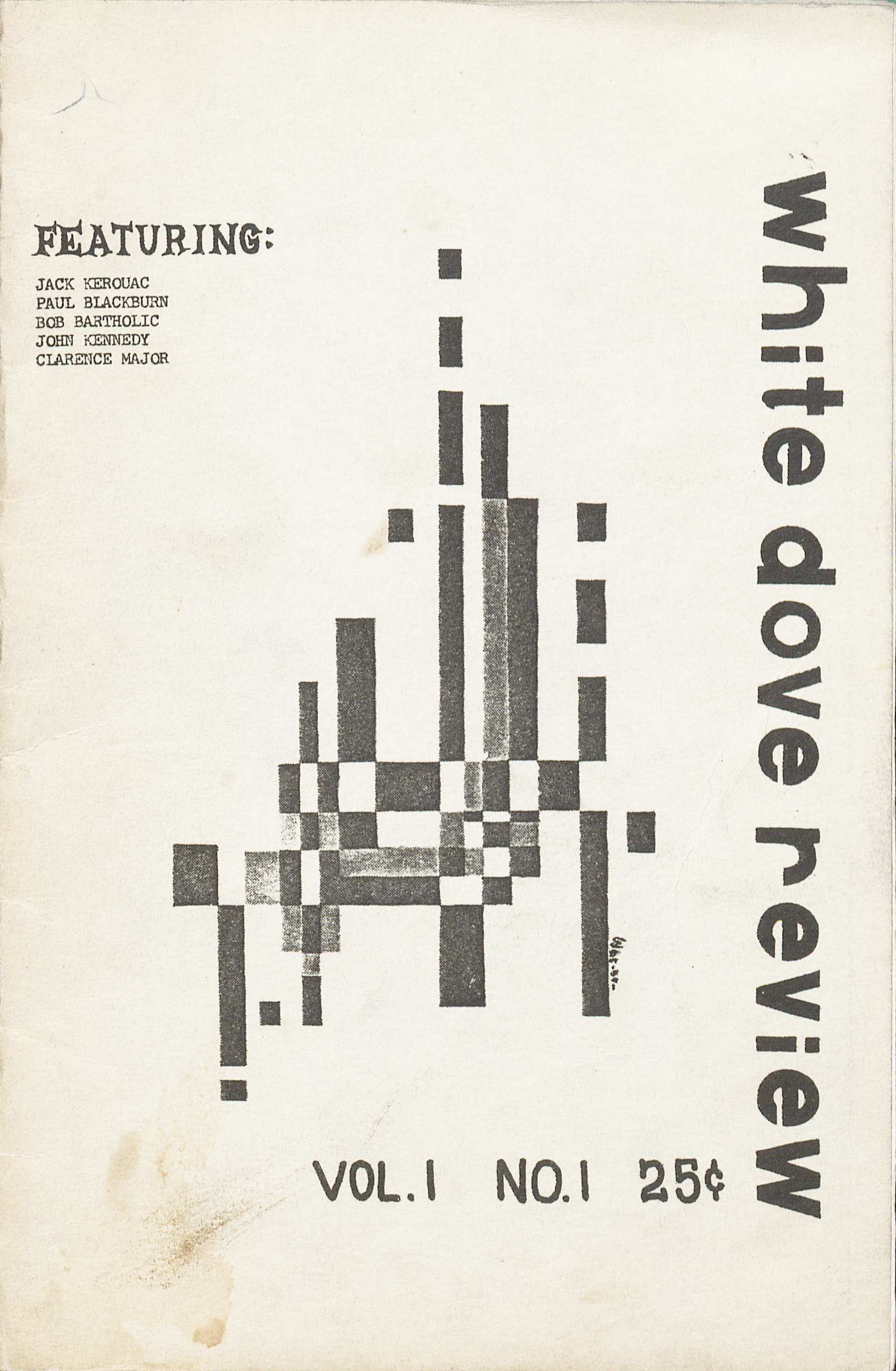

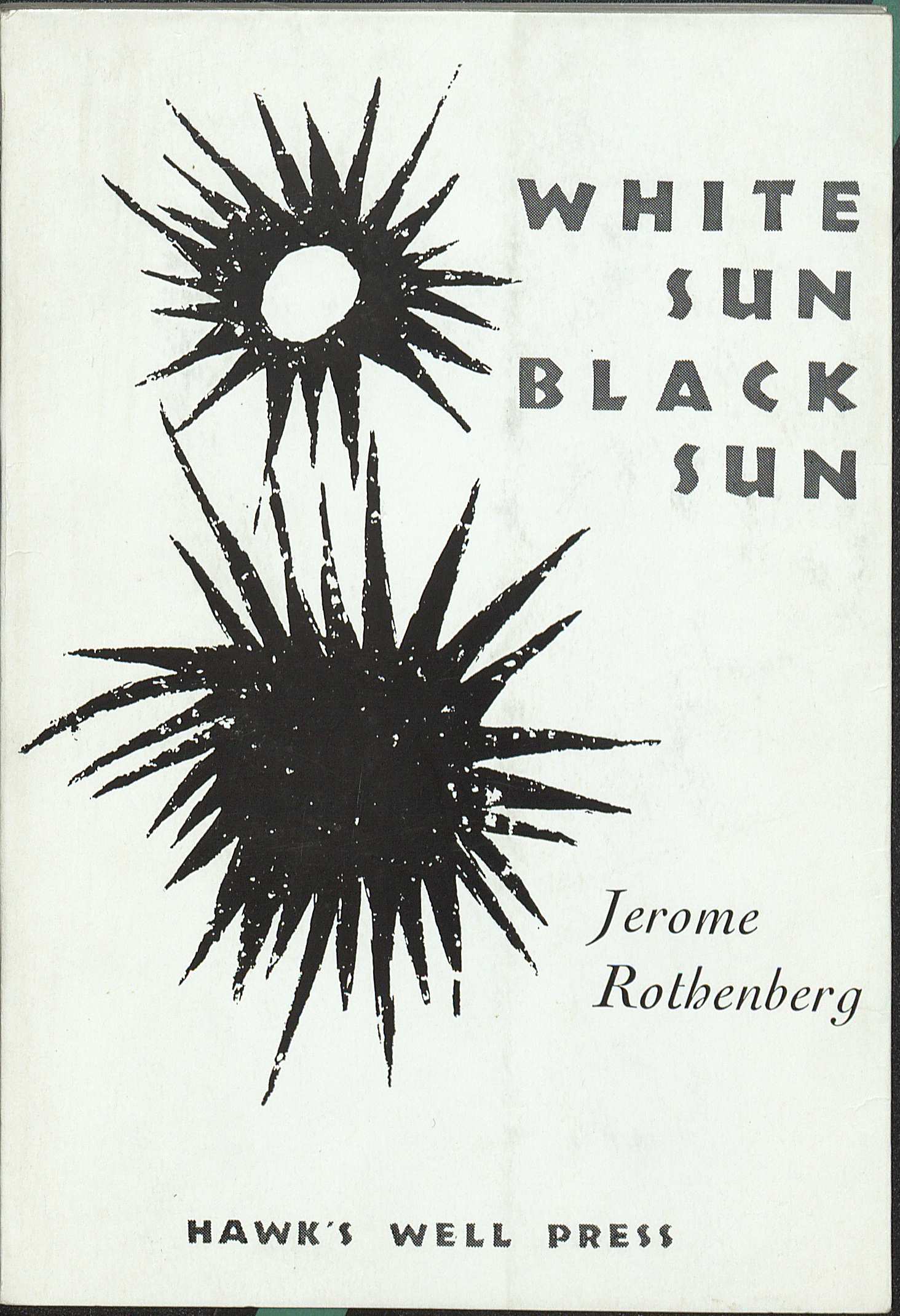

R is for Jerome Rothenberg

Jerome Rothenberg began his writing career translating German poets, notably Gunter Grass and Paul Celan. He published his first book of poetry, White Sun Black Sun, under his own imprint, The Hawk’s Well Press, in 1959. The press published a number of works by beat and avant-garde poets, including Diane Wakoski and Robert Kelly. Rothenberg also co-founded two poetry magazines, Poems from the Floating World and Some/thing. A search of our online catalog shows 27 hits for Jerome Rothenberg, 12 for Hawk’s Well Press, four volumes of Poems from the Floating World, and several issues of Some/thing.

Contributed by George Riser, Collections and Instruction Assistant

White Sun Black Sun by Jerome Rothenberg. (PS3568 .O86W5 1960. Marvin Tatum Collection of Contemporary Literature. Image by Petrina Jackson)

Poems from the Floating World, a magazine co-founded by Jerome Rothenberg. (PS580 .P63 v.3. Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature. Image by Petrina Jackson)

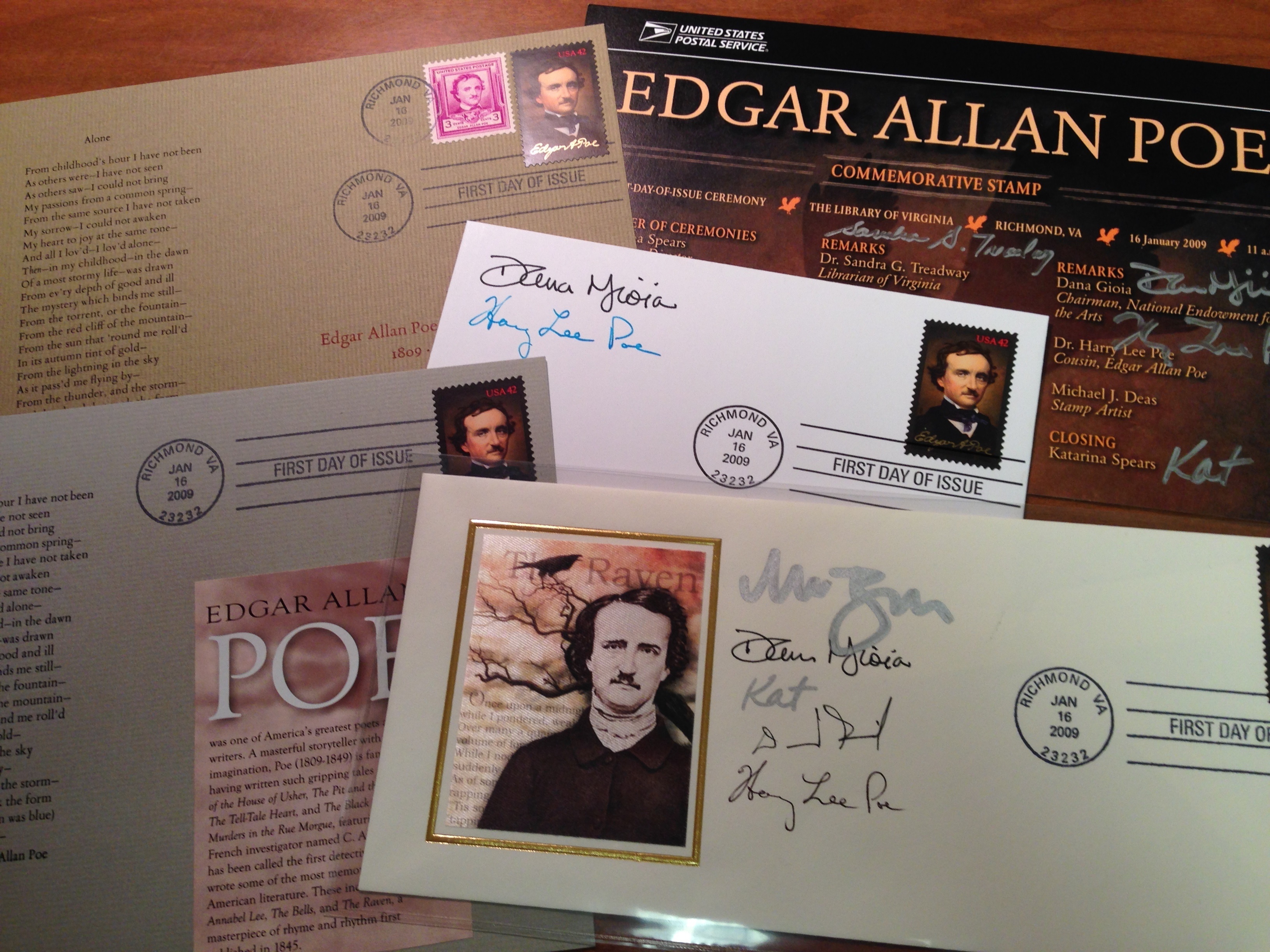

R is for Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám

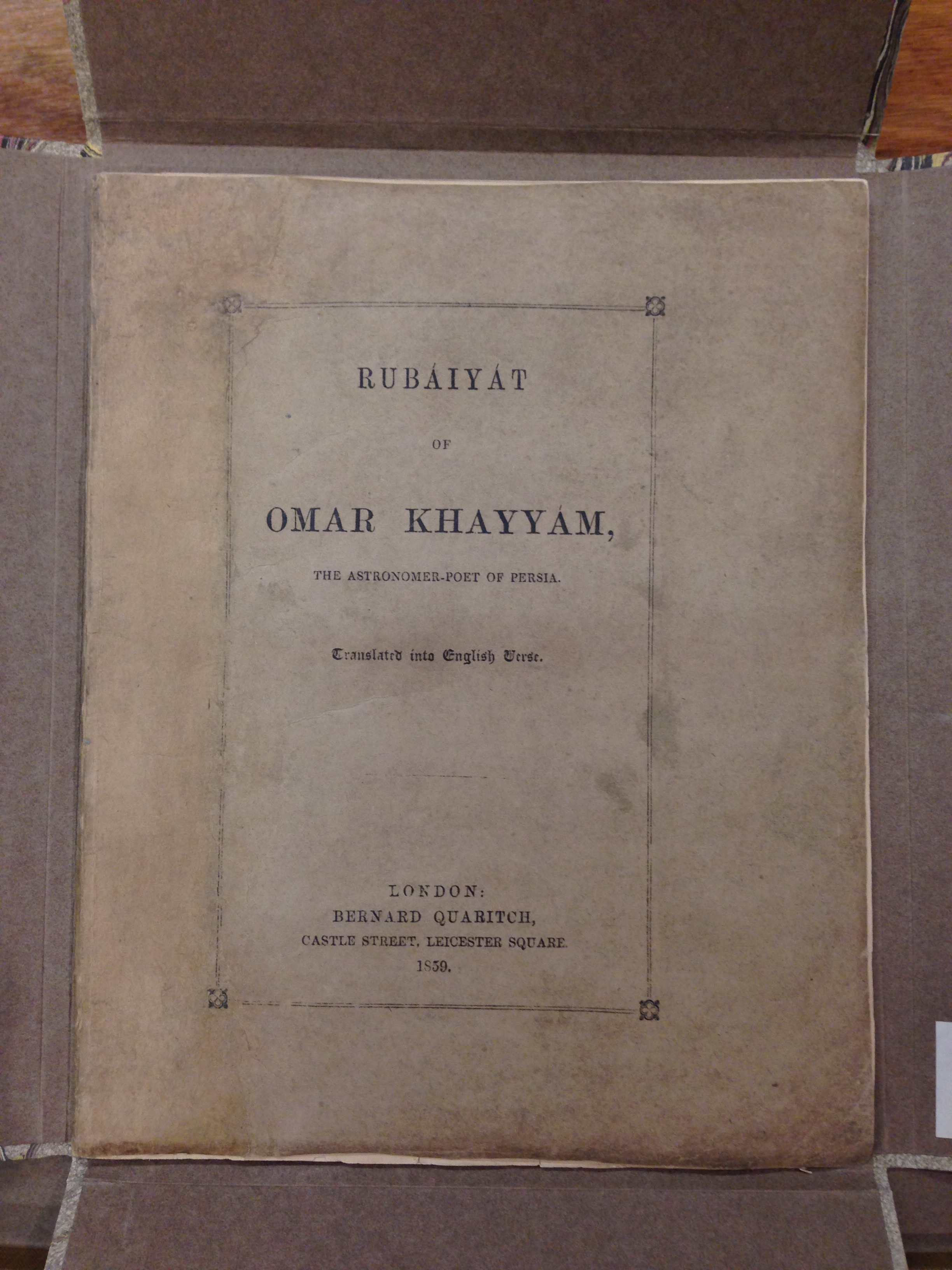

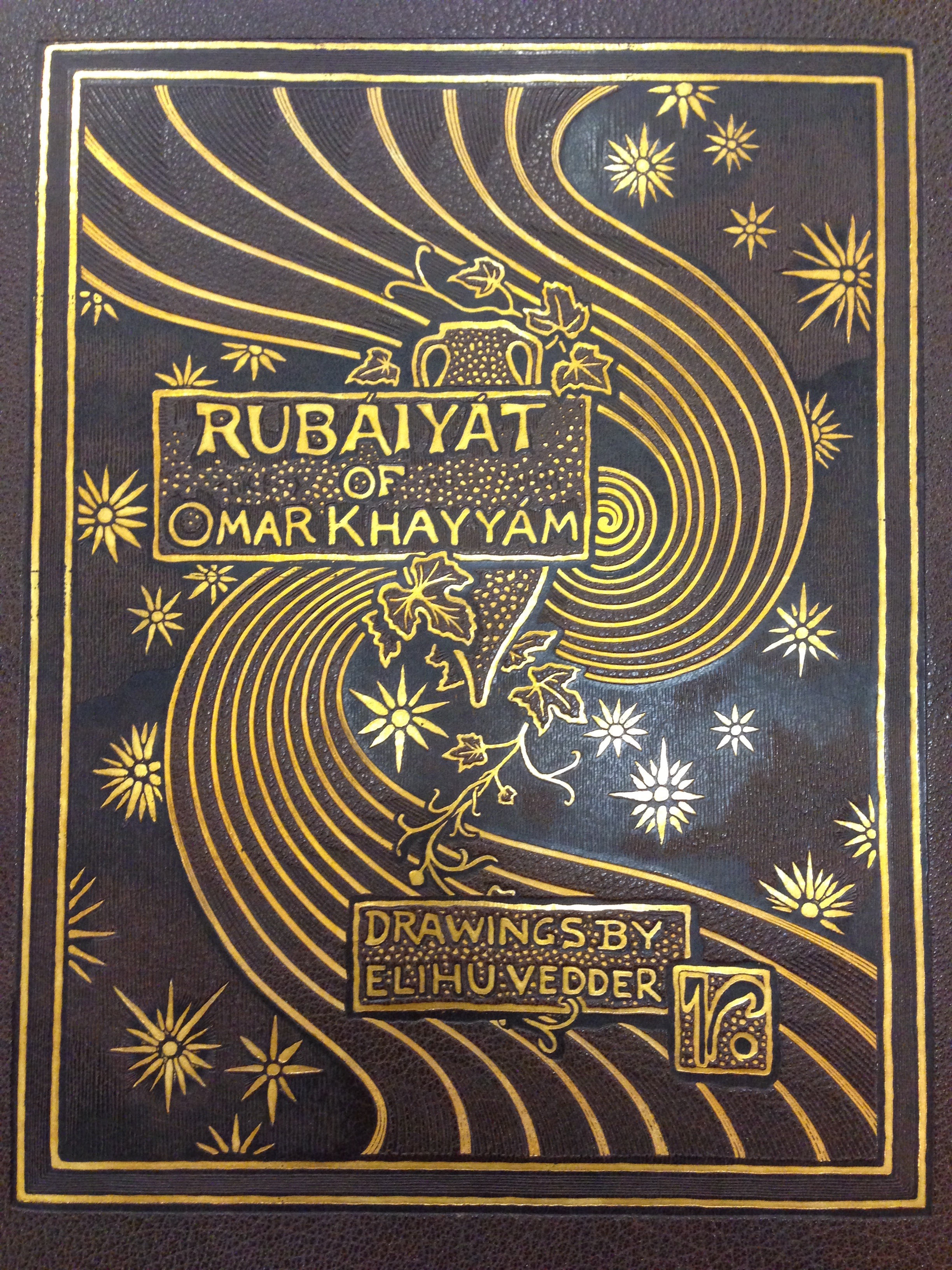

One of the most famous translations in the English language is Edward Fitzgerald’s 1859 Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, a loose interpretation of the Persian astronomer’s eleventh-century verses. It became wildly popular in the United States in the early part of the twentieth century. Eminently collectible, the Rubáiyát was published in hundreds of editions in the late-nineteenth and twentieth centuries—many lavishly illustrated—and was quoted and paraphrased throughout popular culture. Today, it has lost its broad appeal, but libraries like ours contain marvelous materials that document the history of this publishing phenomenon. Special Collections holds more than 400 Rubáiyát editions, of which the two most important are shown here.

Contributed by Molly Schwartzburg, Curator

The first edition of Edward Fitzgerald’s translation (London: Bernard Quaritch, 1859). A great rarity that is virtually unattainable today, the translation went almost unnoticed until two years after its publication, when it was “remaindered” and a copy purchased as a gift for Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who shared it with his friends Charles Algernon Swinburne and William Morris. It swiftly became a popular text among Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic intellectuals. (E 1859 .O53. Tracy W. McGregor Library of English Literature. Image by Molly Schwartzburg)

The first American edition of the Rubáiyát (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1884). This edition has arguably never been surpassed in beauty. Elihu Vedder’s majestic illustrations captured the attention of audiences, and were reprinted in smaller, affordable editions. This copy, of the limited first edition, was printed on Japanese paper and is number 100 of an edition of 100. (PK 6513 .A1 1884. Gift of Mrs. Thos. V. Dudley. Image by Molly Schwartzburg)

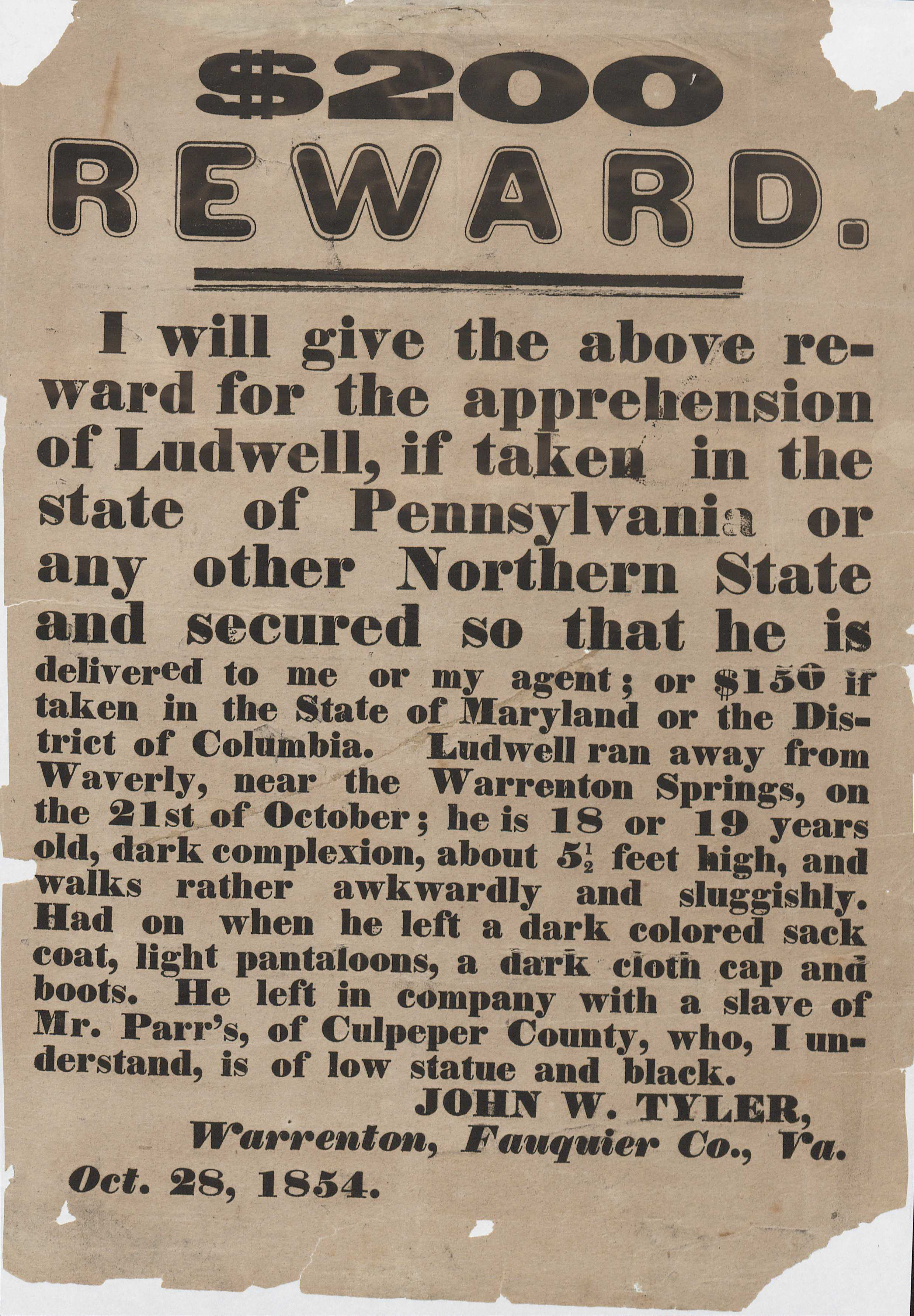

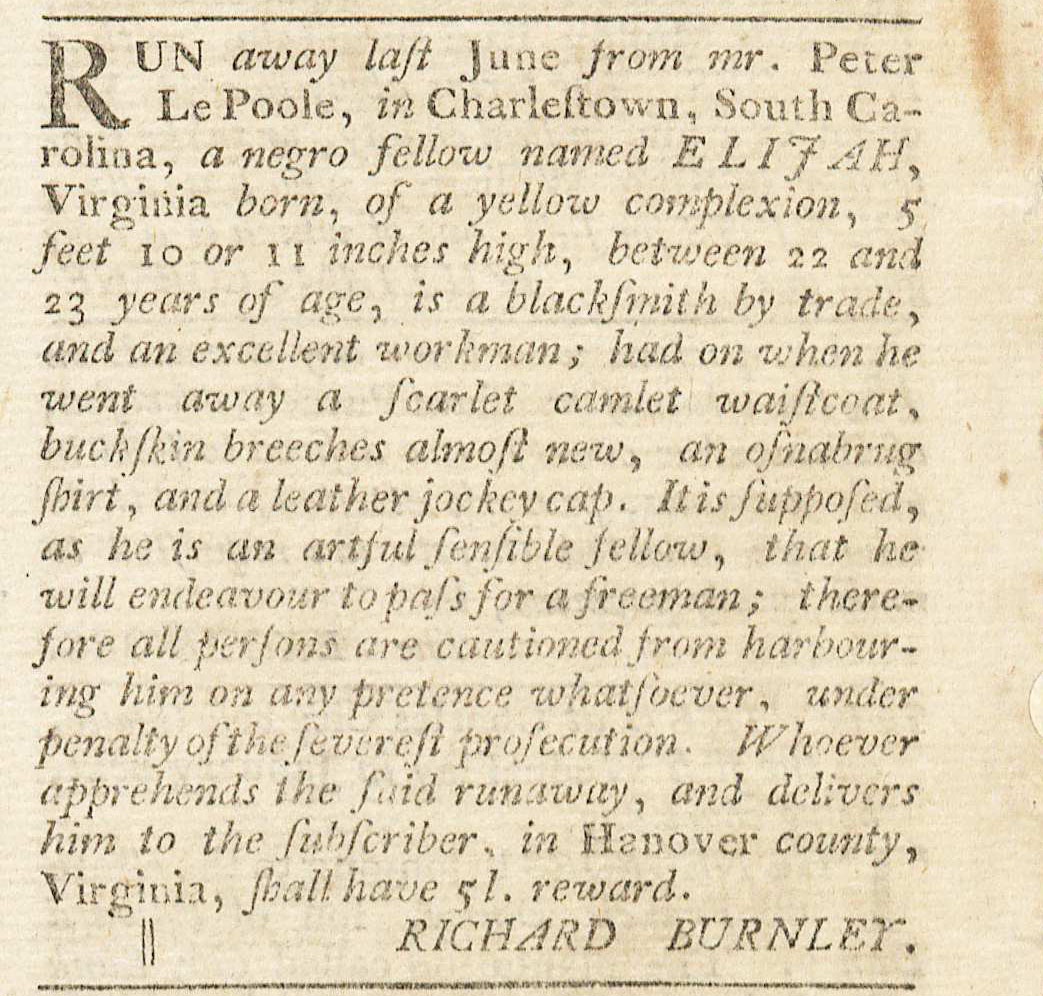

R is for Runaway

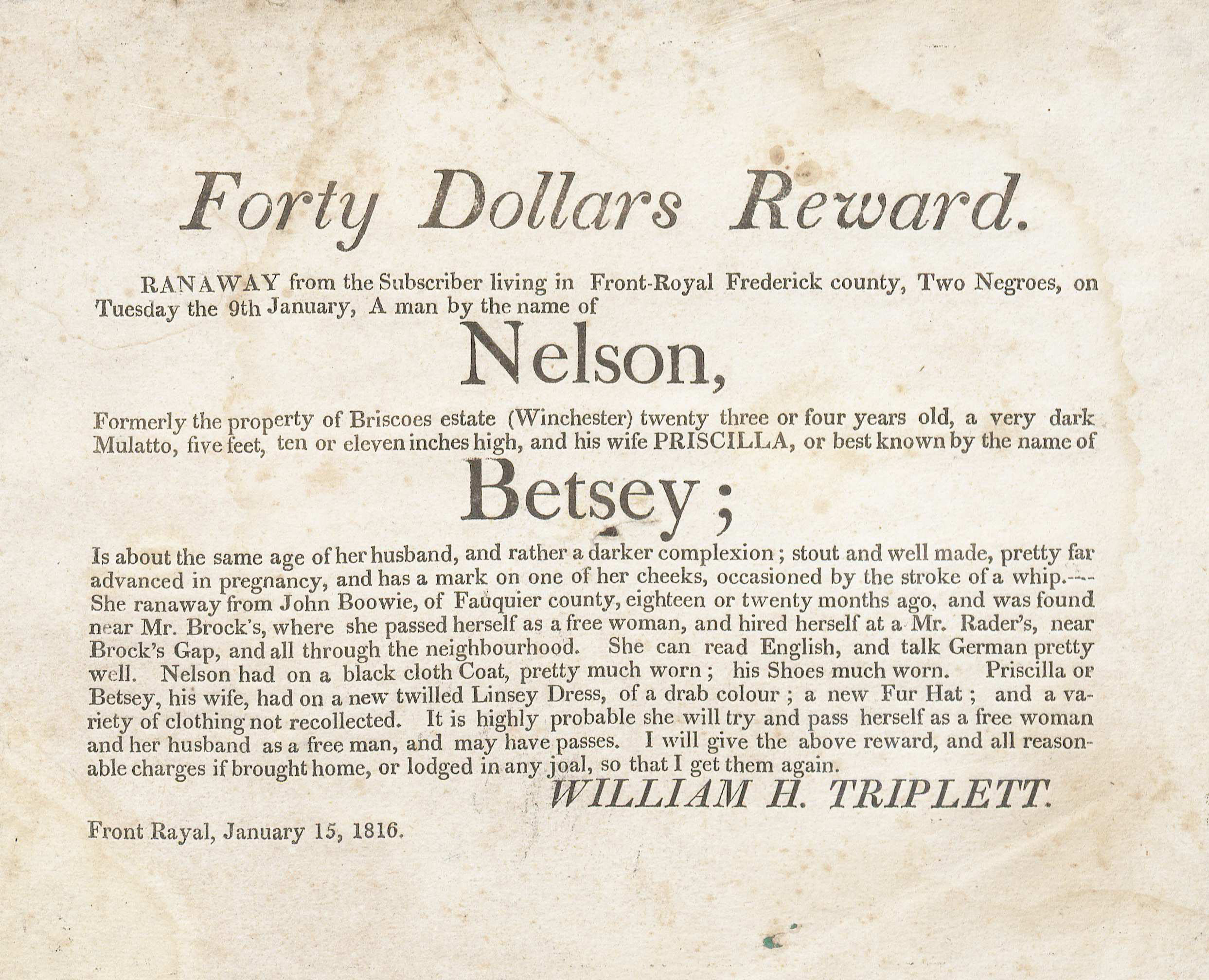

In the antebellum South advertisements seeking to retrieve fugitive slaves were a common part of life. These advertisements were printed in newspapers and as broadsides that were posted in public locations such as courthouses and post offices. The advertisements provide some of the very few instances of personal descriptions of enslaved individuals. In addition to physical description, the advertisements often include description of clothing, tools, and equipment taken by the fugitive, special skills, and, possible destinations. Virginia was well-positioned geographically for escape attempts and some fugitives were able to reach free states.

Contributed by Edward Gaynor, Head of Description and Specialist for Virginiana and University Archives

Runaway advertisement, 1816. (Broadside 1816. T75. Purchased from the Byrd Fund, 2001/2002. Image by Petrina Jackson)

Runaway advertisement, 1854. (Broadside 1854 .T95. Purchased from the Robert and Virginia Tunstall Trust Fund, 2011/2012. Image by Petrina Jackson)

Runaway advertisement from the the Virginia Gazette, November 29, 1776. (Virginia Gazette. Image by Petrina Jackson)

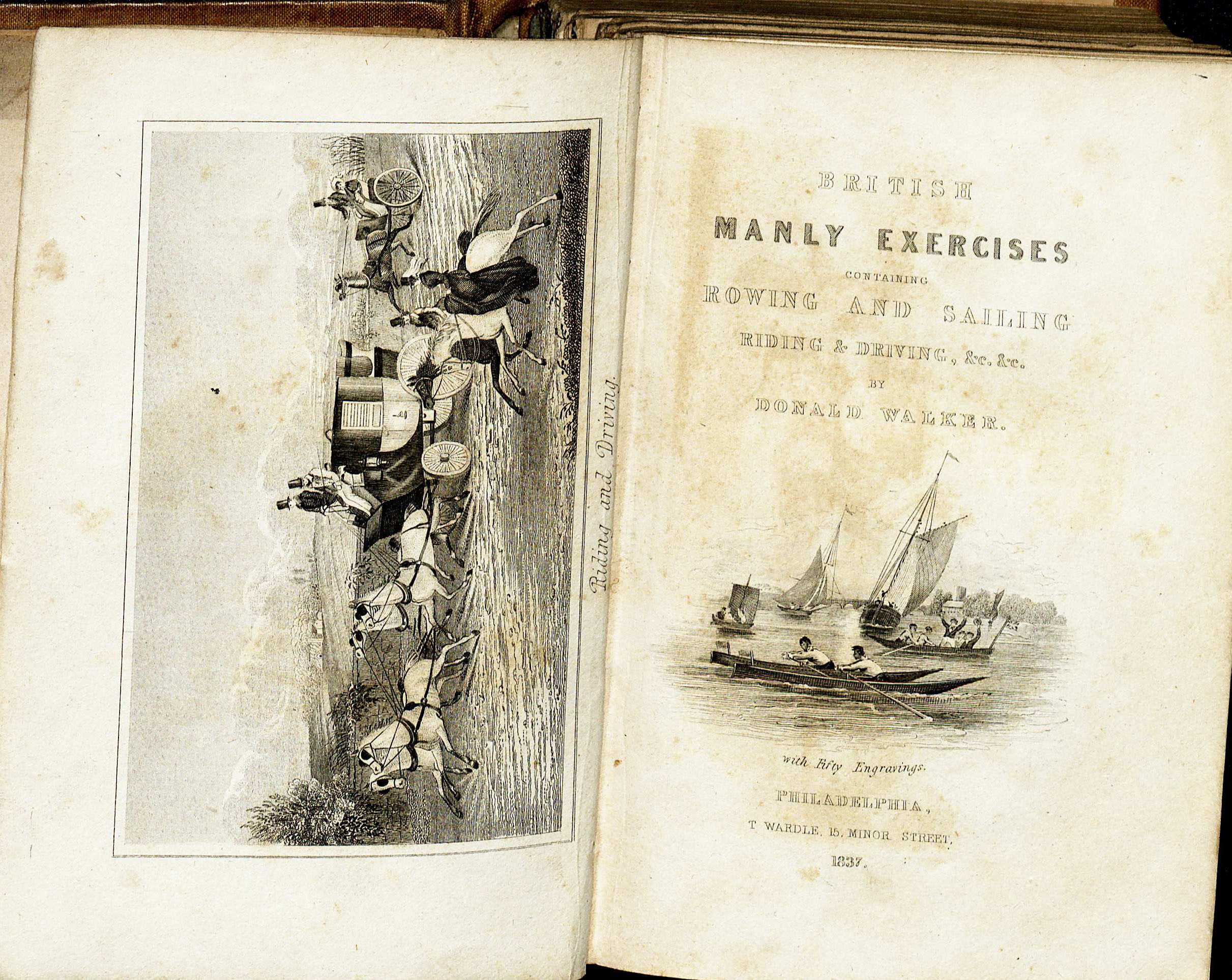

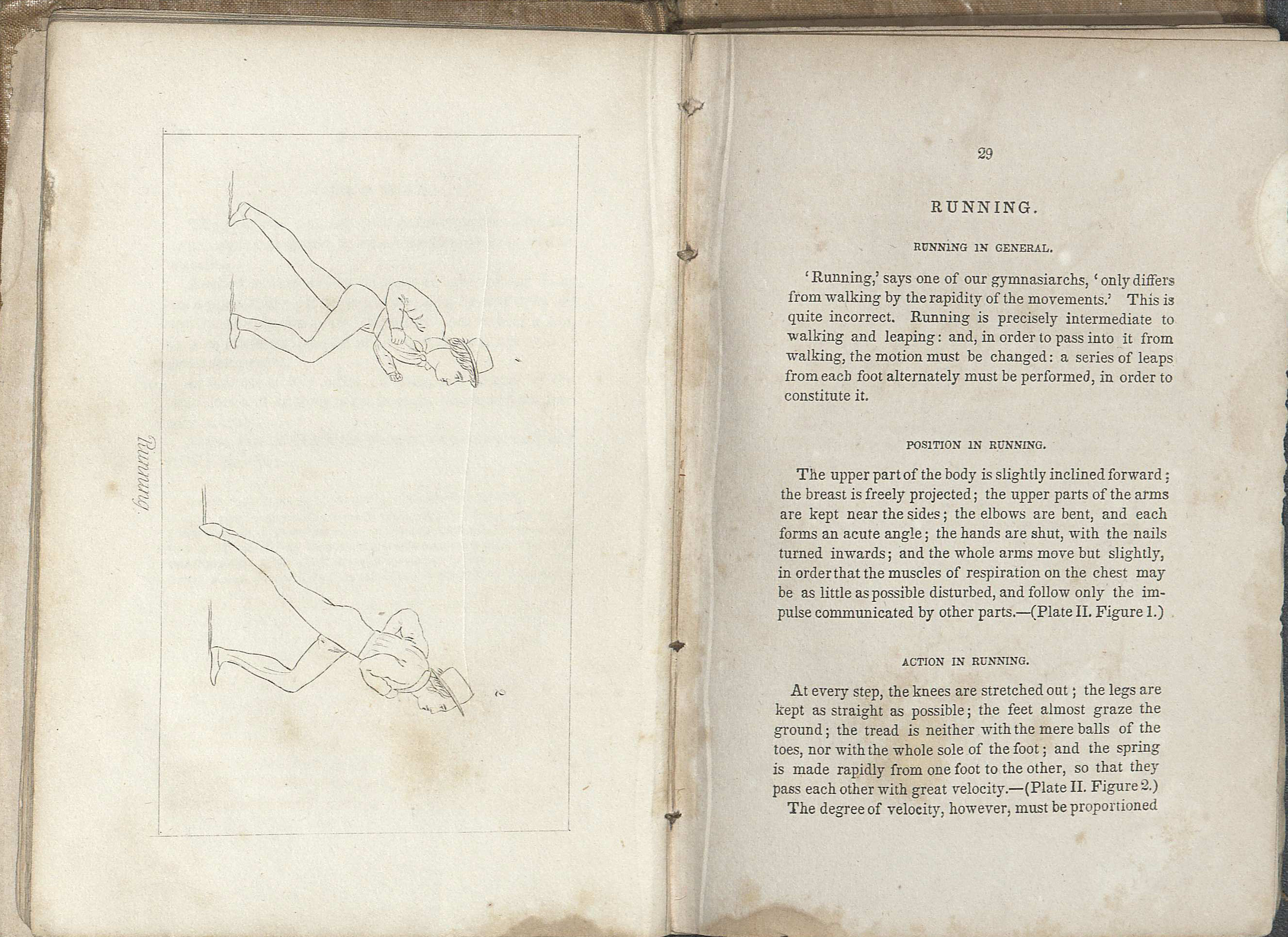

R is for Running

Our online catalog findings are few when it comes to running as a hobby or sport, but they include wonderful images of running, such as at U.Va. track meets and a 1915 Sussex County Virginia School Fair with boys in billowing clothes. When performing a keyword search using the word “running,” approximately 2,000 hits appear. The top hit, appropriately, is “Running Shorts,” a newsletter by the local track club.

Contributed by Anne Causey, Public Services Assistant

Frontispiece and title page of British Manly Exercises by Donald Walker. (GV703.W3 1837. Image by Anne Causey )

Running illustration and description from British Manly Exercises (GV703.W3 1837. Image by Anne Causey)

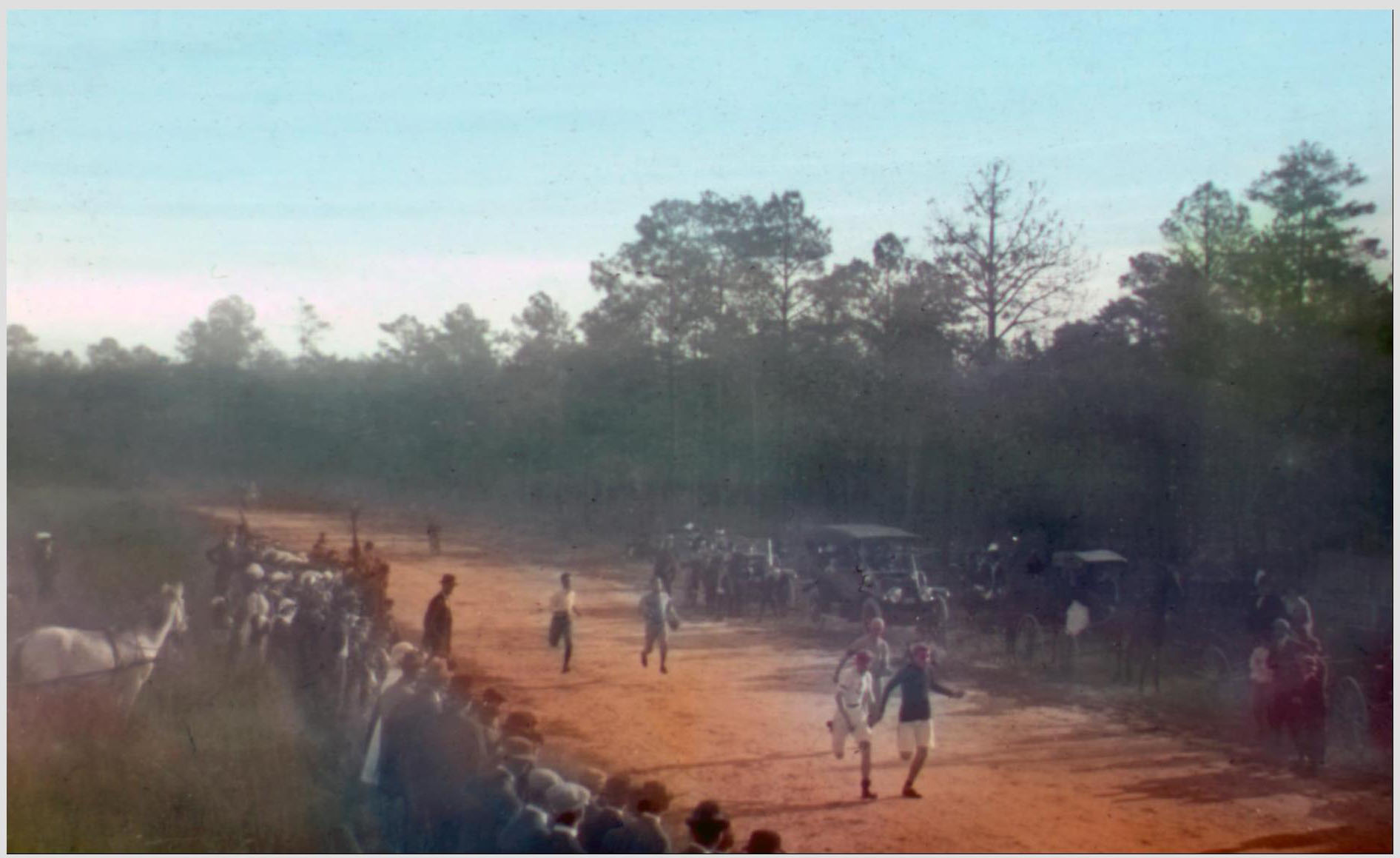

Track Meet, 1915. (MSS 3072, 3072-a. The Jackson Davis Collection of African American Photographs. Image by Digital Curation Services)

This concludes “R,” the last alphabetical installation of 2013. See you again in the new year when we continue with the letter “S.”