This week, we are pleased to feature a guest post by Caroline Newcomb, 4th year student in the College of Arts and Sciences and Special Collections instruction assistant.

***

Most students at U.Va. never have the opportunity to enter the stacks at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. As such, most students have no idea what it’s like down there. Let me give you a description. The place is practically a bomb shelter. Accessible only with a security badge, the stacks are well underground, designed to preserve and protect the collection of over 13 million manuscripts, 325,000 rare books, 5,000 maps, 3.6 million University Archives items, 250,000 photos, 4,000 broadsides and countless other items from all matters of destruction. If things went wrong on Grounds, I would hide in the stacks. That being said, the stacks can also be a bit scary. Especially late at night, after most people have left, you are one of only two people “under grounds,” and you’re searching for a gun.

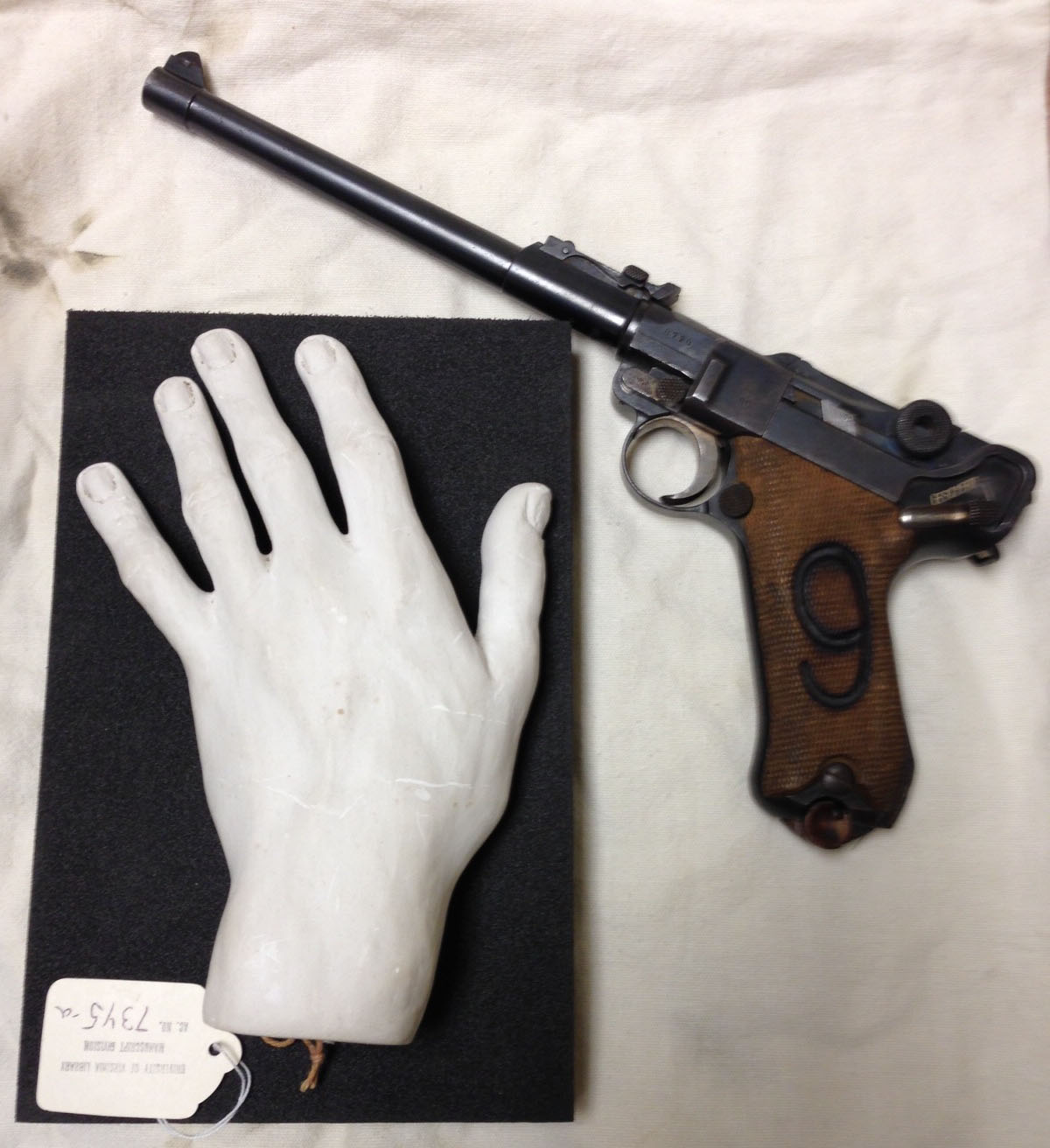

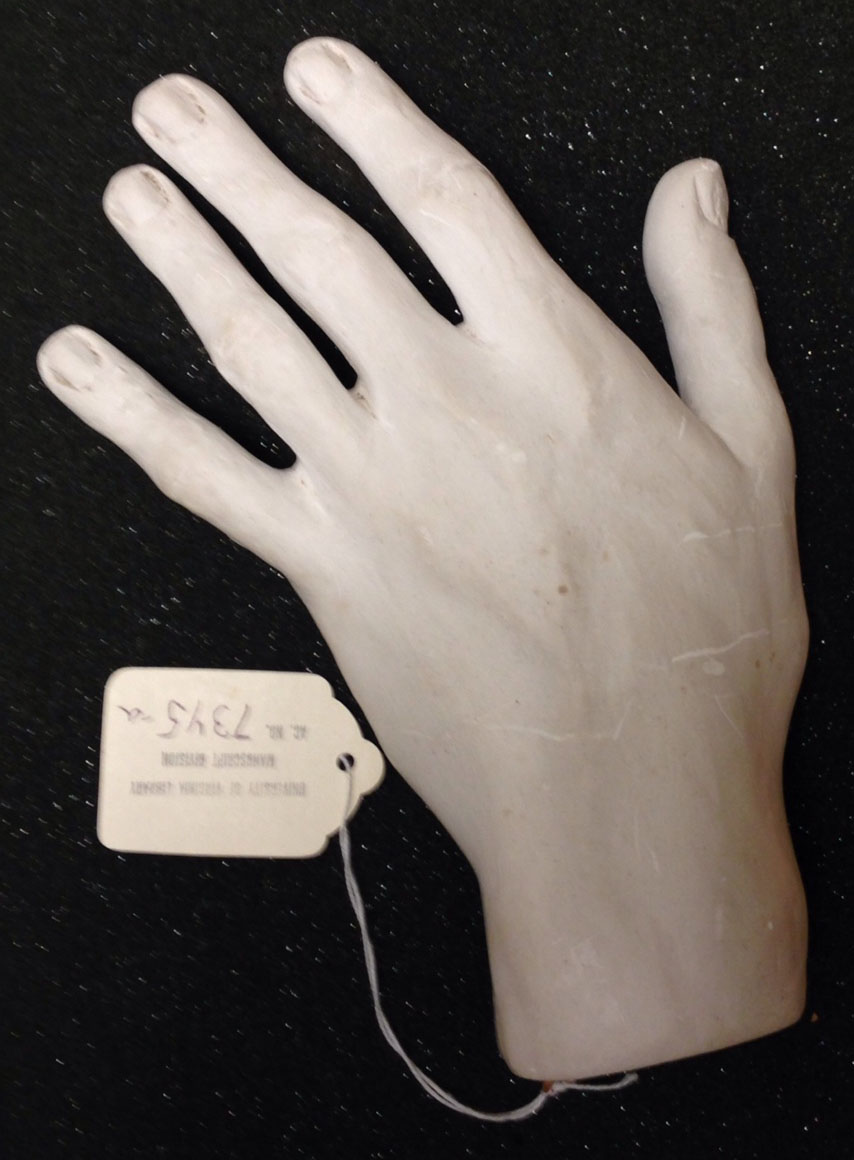

Yep. That’s right, a gun. Petrina Jackson, my boss, had sent me on a mission to find the German Luger the library holds for her USEM the next day. Naturally, it was in the far-off corner of the stacks furthest from any doors, where people rarely go. Just where I wanted to look for a gun that belonged to a German officer in World War I—please note my sarcasm. Nevertheless I steeled myself, and searched that isolated corner and found the box where I thought the gun was kept. Not wanting to have to embark on this gun-finding mission a second time, I wanted to ensure that the gun was actually in this particular box. So I pulled it down in that isolated corner, set it down, and lifted off the lid–only to find a preserved human hand inches from my face.

Needless to say, I screamed. And being in an isolated corner of stacks, no one came to my rescue. OK, “screamed” might be a bit of an exaggeration, but the fact that I found a hand in the process of looking for a German Luger was enough to shake me up.

Upon closer inspection, I ascertained that this particular hand was not petrified; but rather, was a cast of someone’s hand– albeit a very convincing cast. Regardless, I wasn’t about to search the box any further for the gun, which, as it turns out, wasn’t even in that box anyway.

But why on earth does the Special Collections library hold a cast of a hand? Whose hand was it?

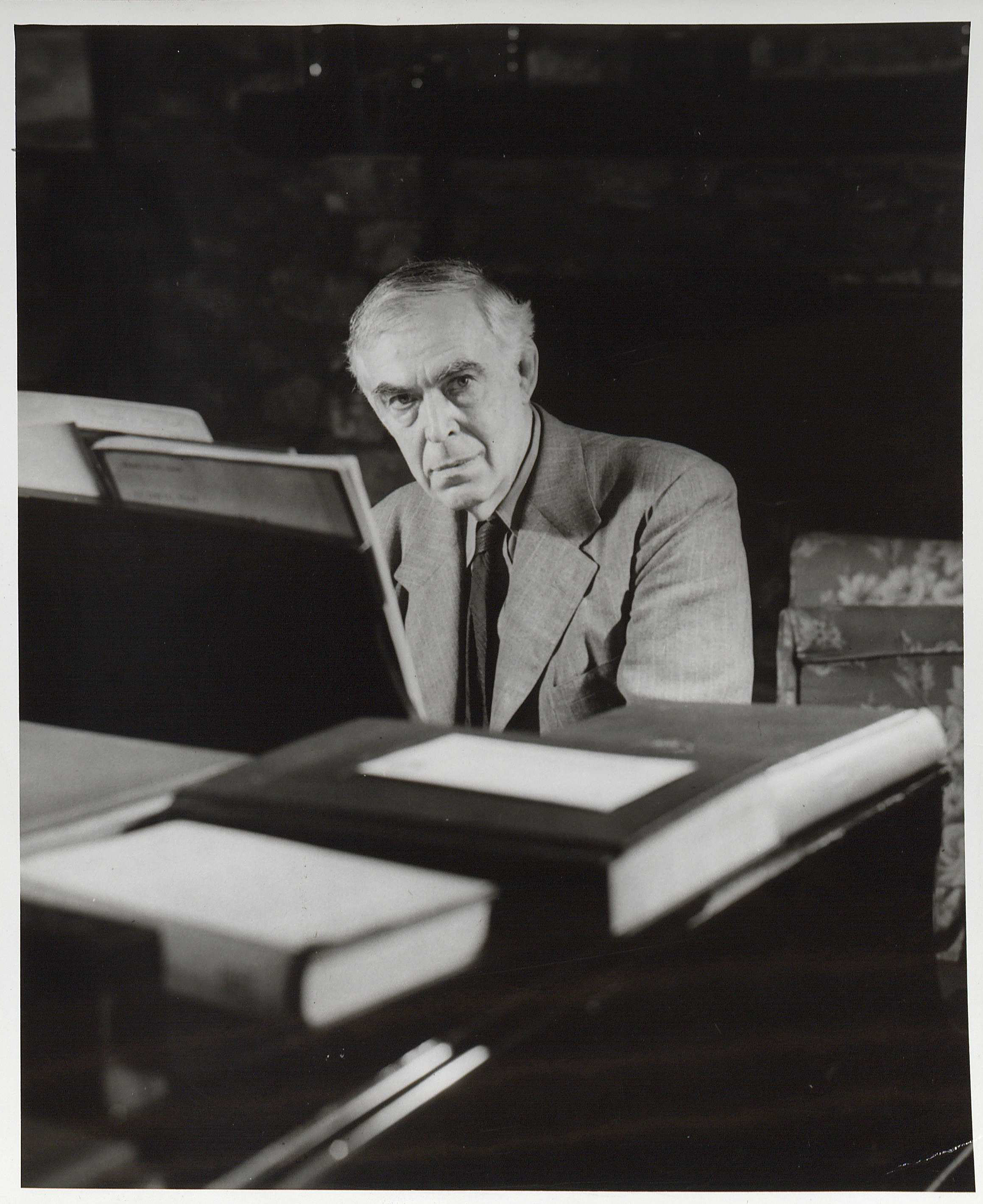

As it so happens, this particular hand belonged to the well-known John Powell, whose extensive personal papers are housed in Special Collections.

John Powell devoted much of his life to music. In addition to trying to establish a chair of music here at U.Va., he wrote and performed music around the country.

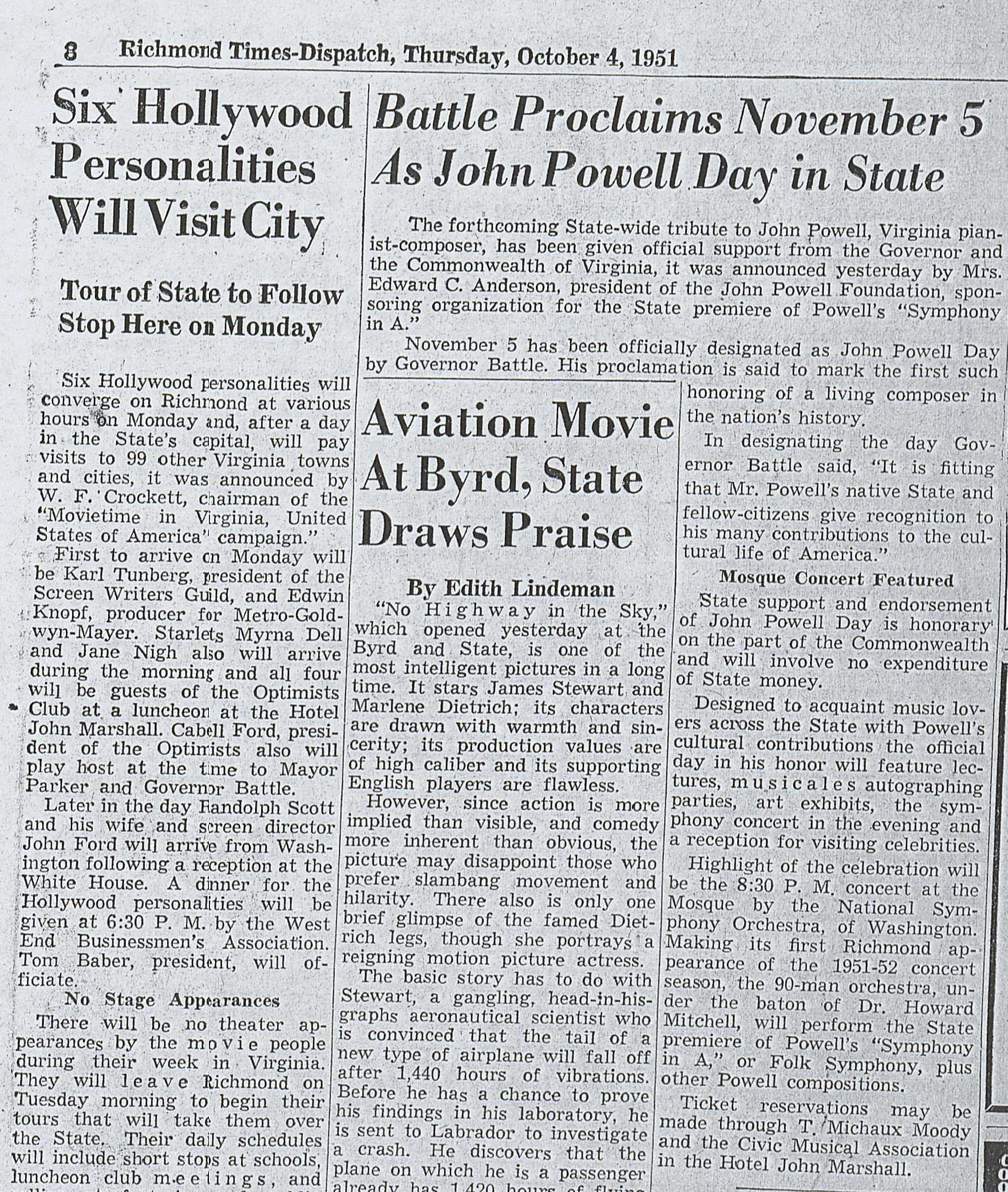

In fact, he was so talented and well-known that when his Symphony in A premiered on November 5, 1951, the governor declared it “John Powell Day.” “It is fitting,” Governor Battle said, “that Mr. Powell’s native State and fellow-citizens give recognition to his many contributions to the cultural life of America”

Newsclipping about “John Powell Day,” featured in the Richmond Times-Dispatch, 4 October 1951. (MSS 7284. Image by Caroline Newcomb)

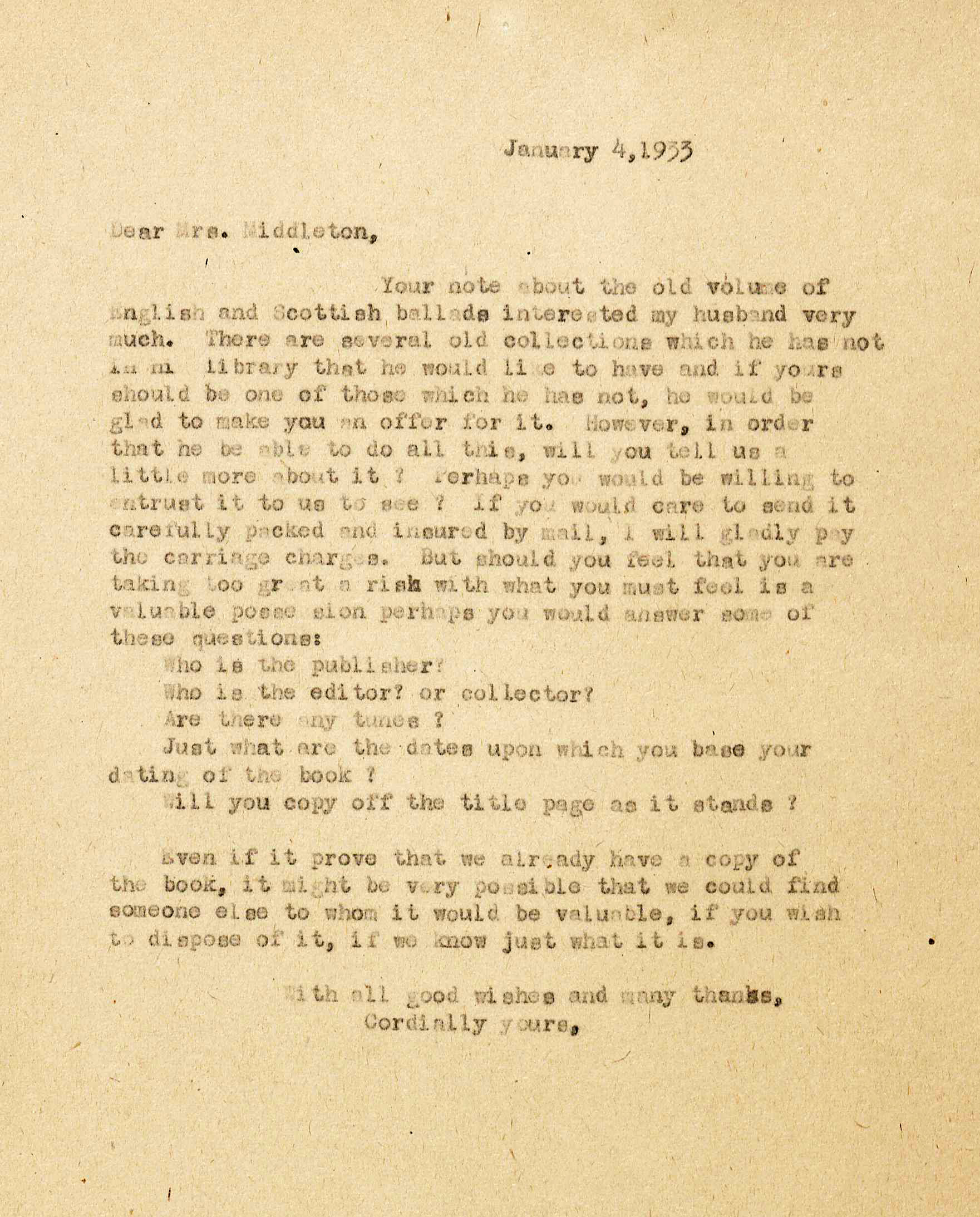

Mr. Powell did more than write and perform music; he also collected it. As an ethno-musicologist, he gathered music written by Anglo-Saxons in an effort to prove not only that his contemporary Anglo-Saxons could write valuable music, but also that Anglo-Saxons had a history of musicianship.

Here is a letter written by John Powell’s wife, Louise, to Mrs. Middleton, detailing a potential purchase of Anglo-Saxon music, 4 January 1933. (MSS 7284. Image by Caroline Newcomb)

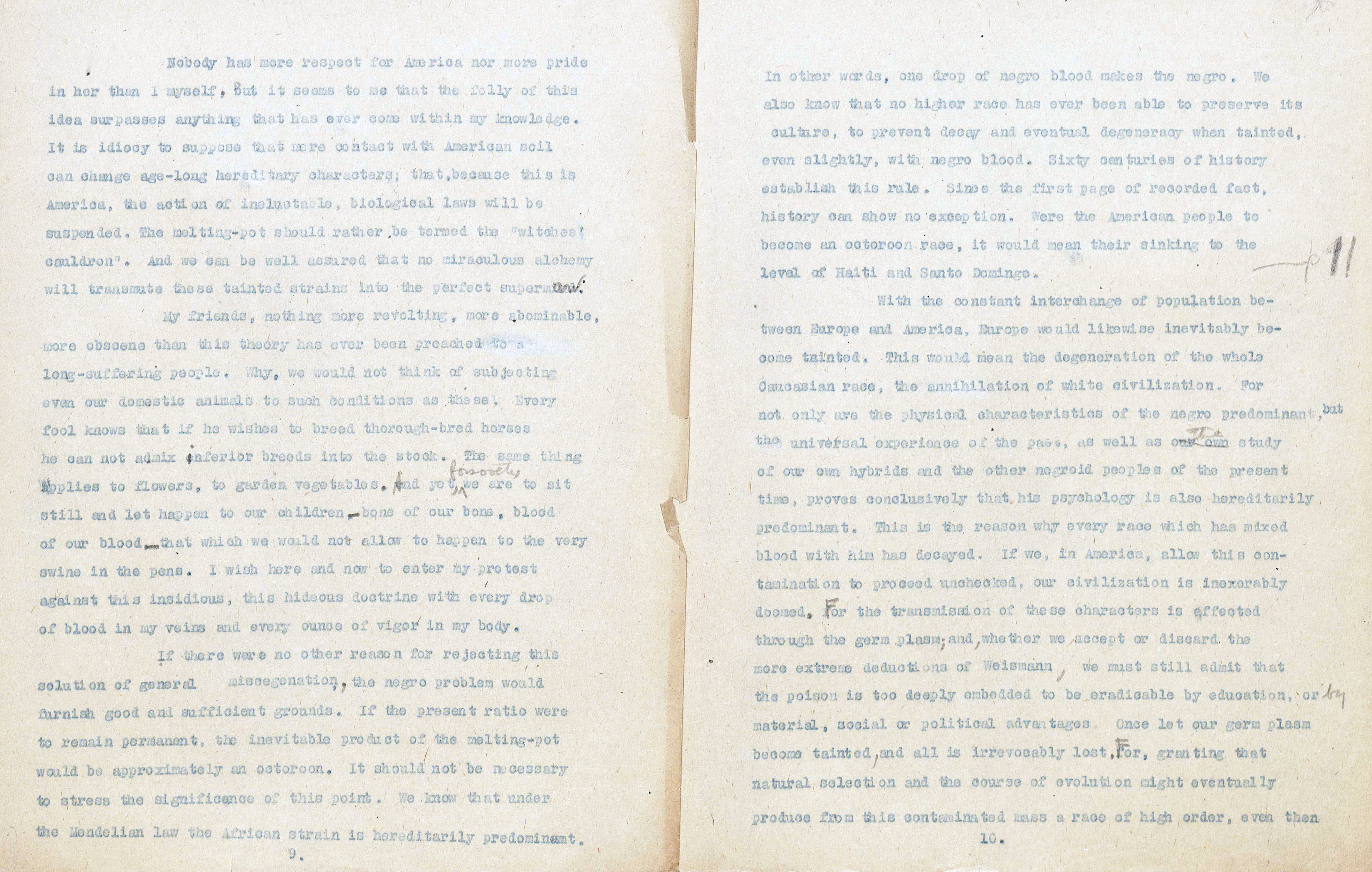

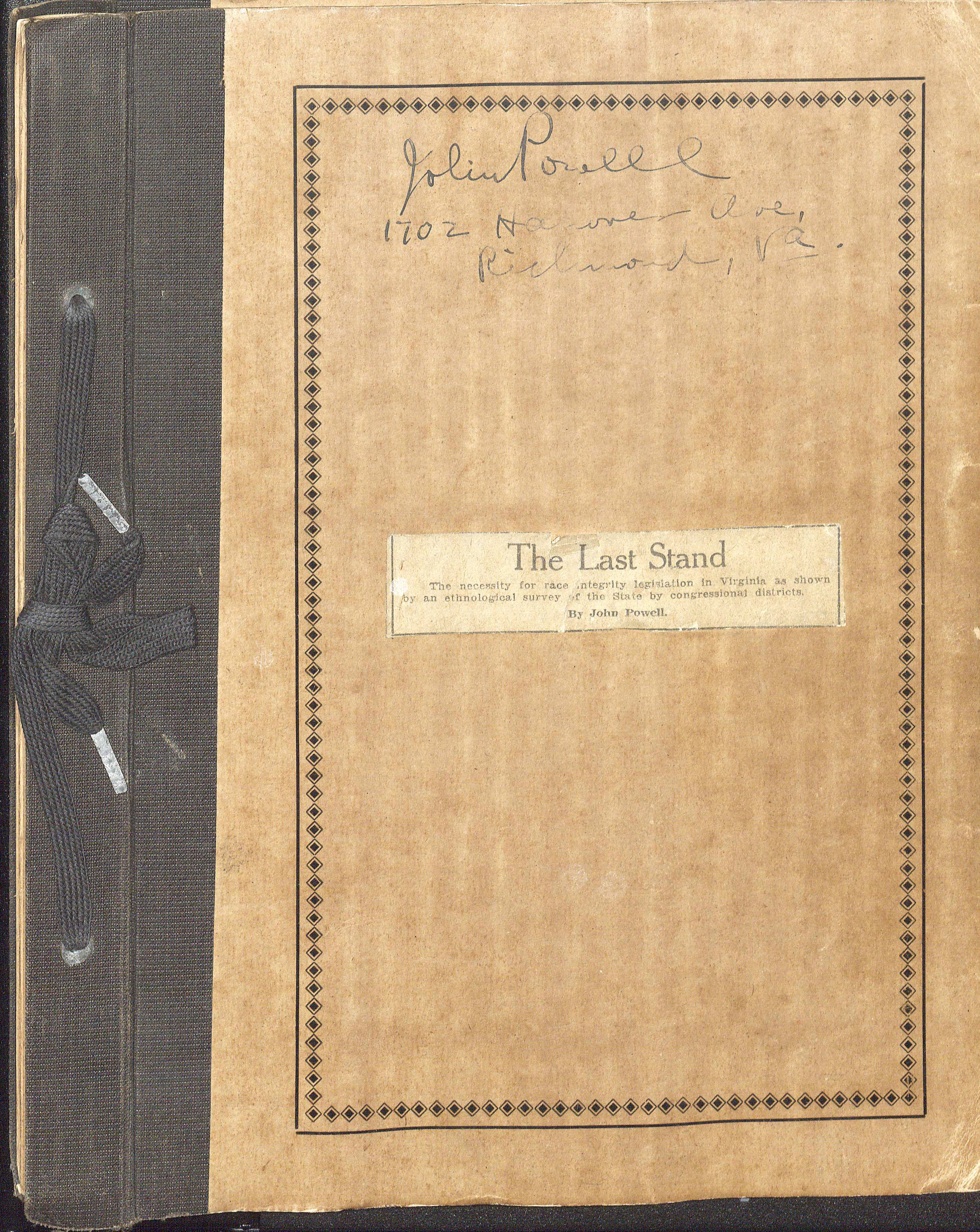

If it seems a bit strange to you—as it did to me—that Powell advocated for and collected specifically Anglo-Saxon music, then your intuition would be right on track. John Powell’s life revolved around more than music. Perhaps even more than a musician, John Powell was a eugenicist. The reason he collected Anglo-Saxon folk music was more about establishing this music as the music of the American Nation, supreme over all other music, than it was about proving Anglo-Saxon musical ability.

In “Music and the Nation” [above], Powell argued that the United States at the time was not a nation, because a nation could only exist when it comprised a population homogeneous in blood, language, culture, and values. America, he further argued, used to be a nation, but ceased to be so when non-Anglo-Saxon immigrants and slaves were permitted or forced to enter the country, respectively. Comparing America’s population unfavorably to thoroughbred horse breeding, he argued, “the immense influx of the lower elements of the European and other continents…debase the average level of intelligence and character of the population.” He pushes for the deportation of non-Anglo-Saxon individuals and groups, as well as for stricter immigration laws, to prevent the further “degradation of white civilization.”

This puts a whole new perspective on the “many contributions to the cultural life of America” that Governor Battle extolled in John Powell.

Writings such as “Music and the Nation” and “The Last Stand” do not even begin to cover the massive efforts Powell made to render The United States an entirely Anglo-Saxon nation. Many of his letters, writings, and other works detail his opinions on the superiority of individuals of so-called “Anglo-Saxon stock” in terms of intelligence, language, and culture. What makes John Powell stand out even more is that his approach to eugenics used not only the usual arguments, but also intersected with music—the other love of his life. Not only did he believe that Anglo-Saxon individuals could compose music; he also believed that Anglo-Saxon music constituted the only true music—the best music.

I never found that German Luger I was looking for that day, but instead spent several days exploring Powell’s collection. Each time I found myself leaving feeling angry and sick to my stomach. Part of me wanted to burn the entire thing—all 47 boxes. However, the reality stands that eugenics constitutes an important part of our history in both Virginia and America—important in its danger, and the fact that notable individuals subscribed to this view. There are 47 boxes in Special Collections dealing with just one of the countless eugenicists in Virginia and America’s history. I may have started out looking for an example of racism, oppression, and genocide abroad, but the reality, as well all should know, is that these horrors exist(ed) here too, and constituted the ideals of touted individuals. That is not something we should ignore, but something we can learn from instead.

Cast of John Powell’s hand and German Luger from a collection of German World War I and II materials, 1917. (MSS 7345-a and MSS 9405-u. Image by Caroline Newcomb)

***

Thanks for this article. I share your feelings about Powell. Doing some research on the history of the Virginia Glee Club, I came across him and read further with a mix of fascination and horror.

As with so much that relates to what Faulkner called the “original sin” of the South, the good he did (big donations to the University, his work as a teacher) is inextricably bound with the more horrifying parts of his legacy, like his contribution to the Racial Integrity Act of 1924 via the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America.

I wrote a bit about him on the Virginia Glee Club Wiki (http://virginiagleeclub.wikia.com/wiki/John_Powell) – they made him an honorary member in the 1930s, presumably for his support of music at the University rather than his eugenics views, but I suppose you never know.