My previous post on the acquisition of U.Va.’s first papyrus manuscript has been a popular one, made more so by a subsequent U.Va. news release. Two readers have since contacted me with a question unaddressed in the blog post and news release (the latter now amended): What is the document’s provenance, that is, its recent ownership history? This follow-up post seeks to summarize what little is known at this point about its provenance, acknowledge an error of judgment in this instance, and touch upon an important ethical issue concerning the antiquities trade.

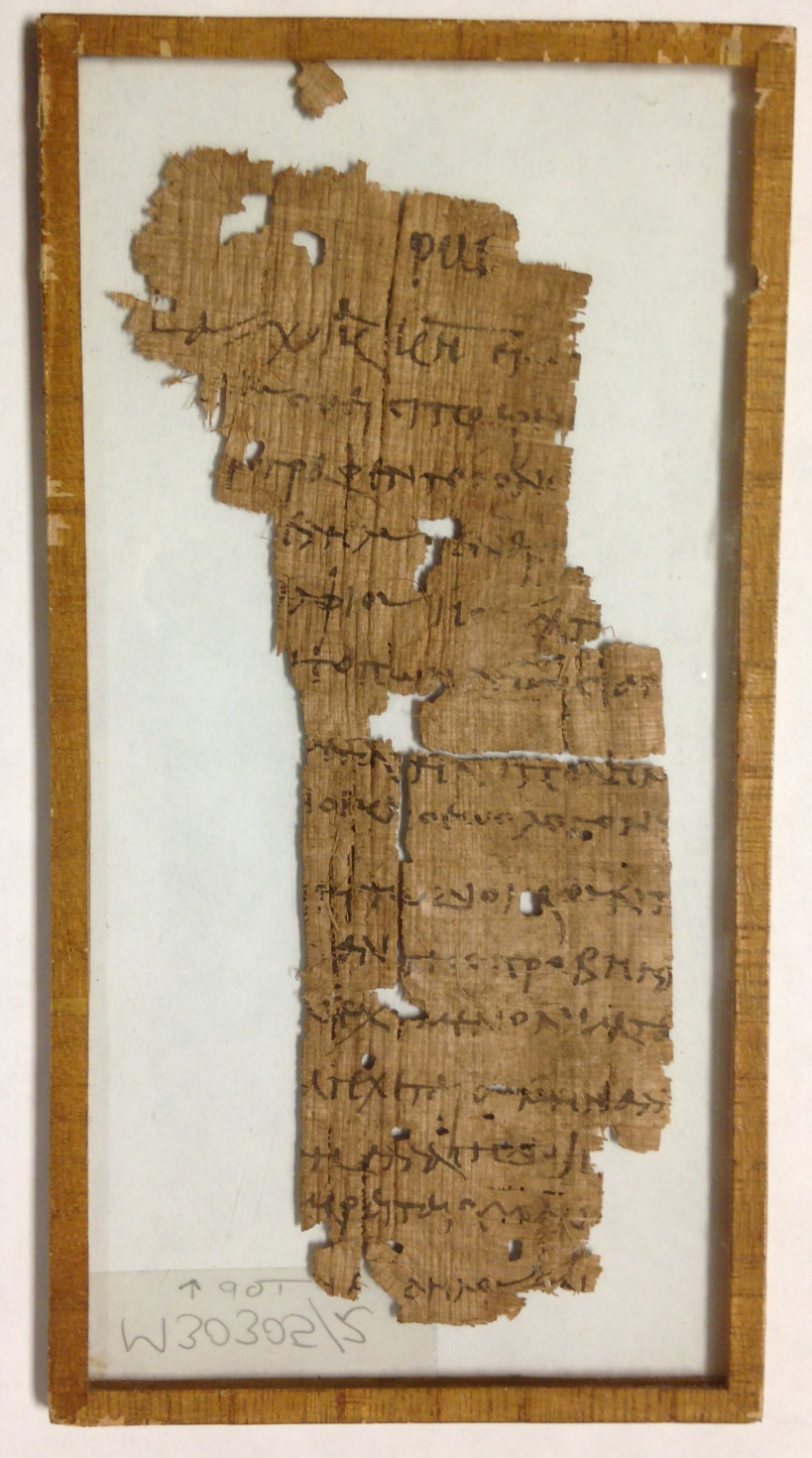

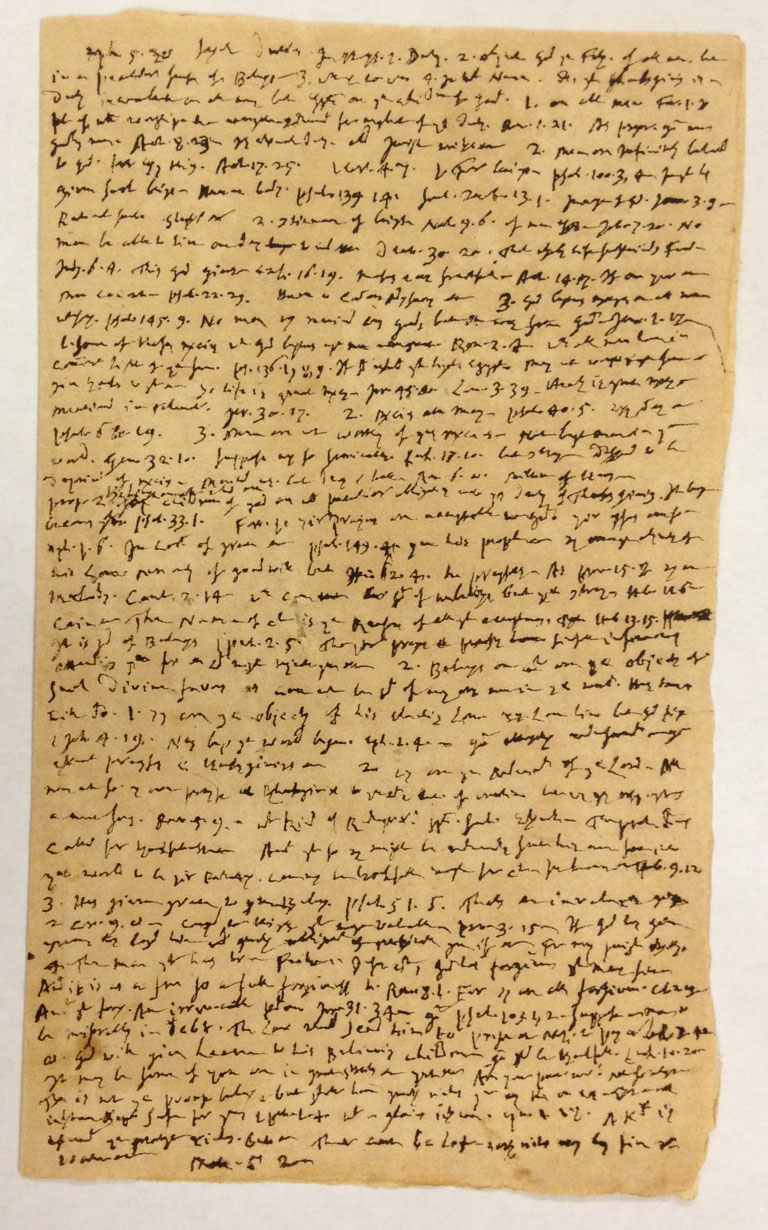

P. Virginia 1, U.Va.’s first papyrus document, measures 16.5 x 8 cm. It was written in Greek, probably in Egypt during the 3rd century CE. Purchased on the Associates Endowment Fund.

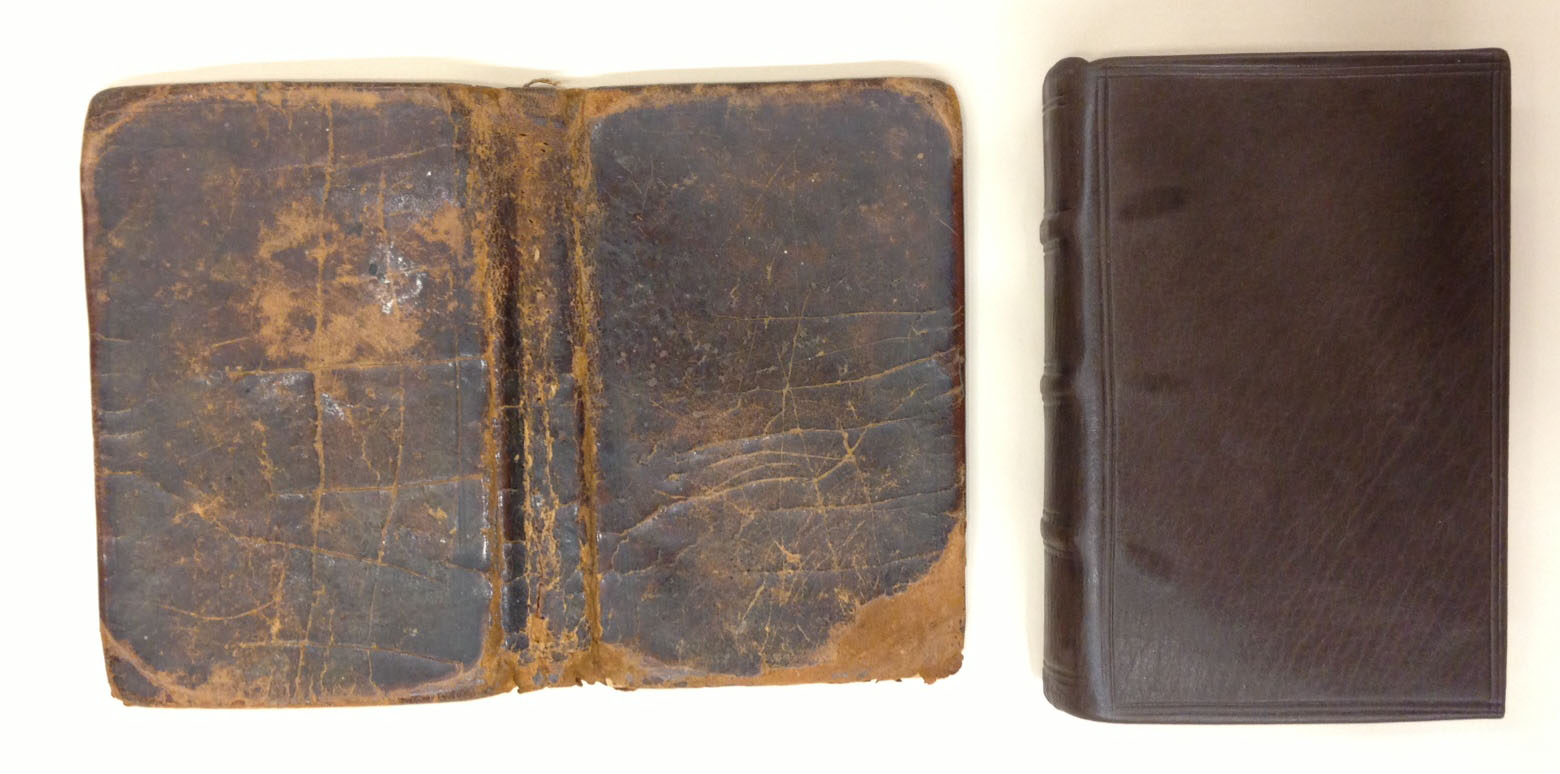

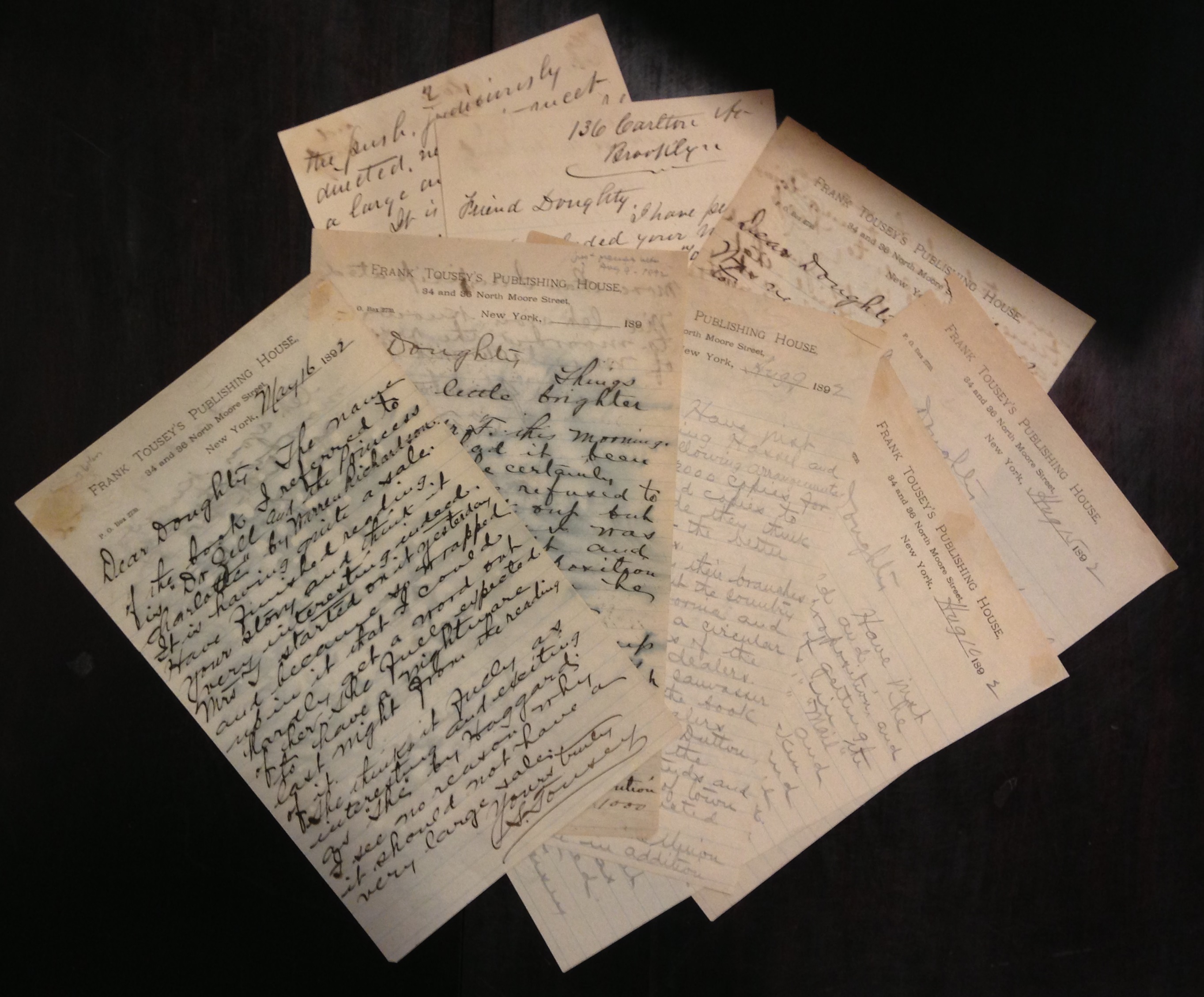

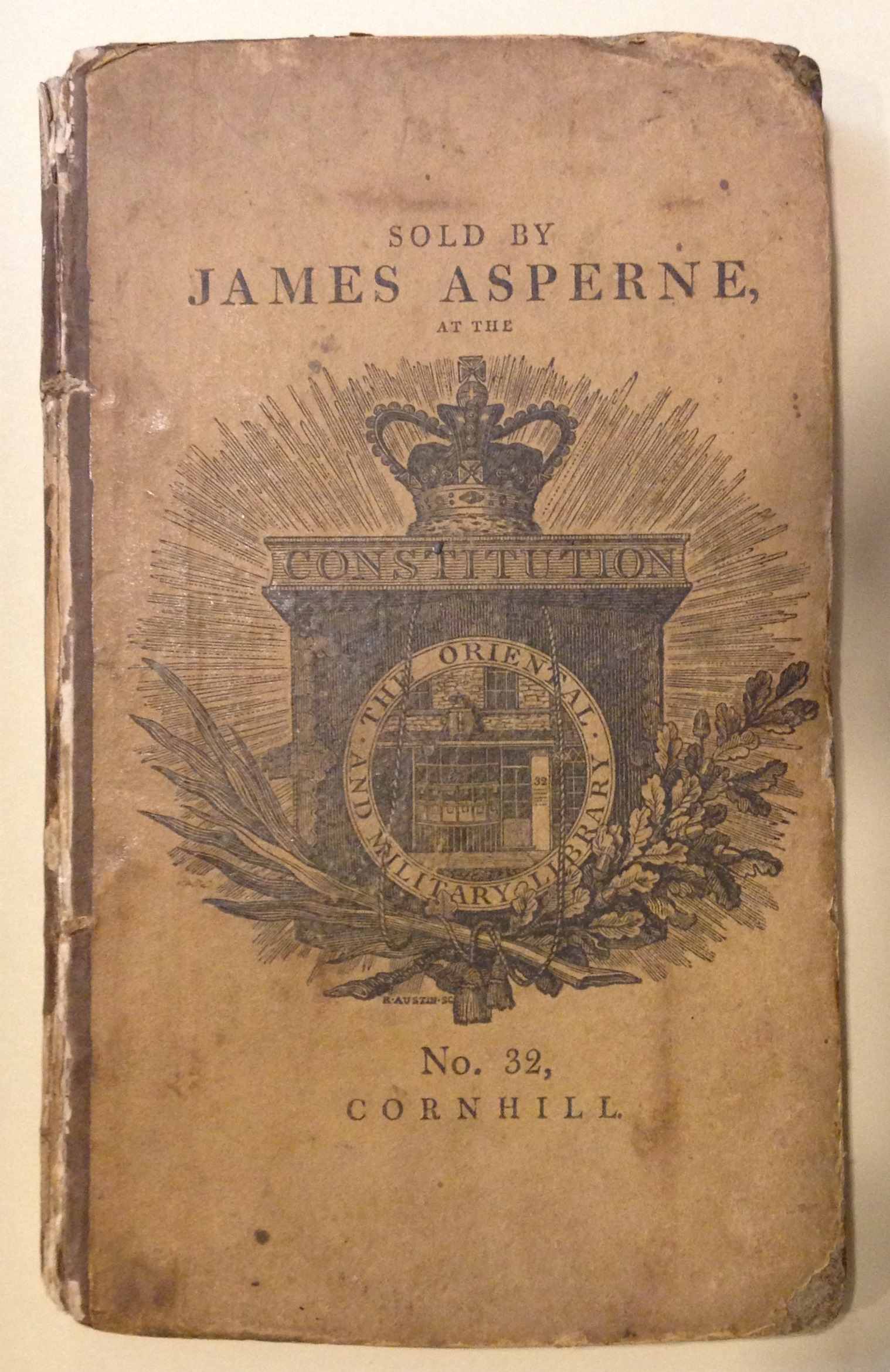

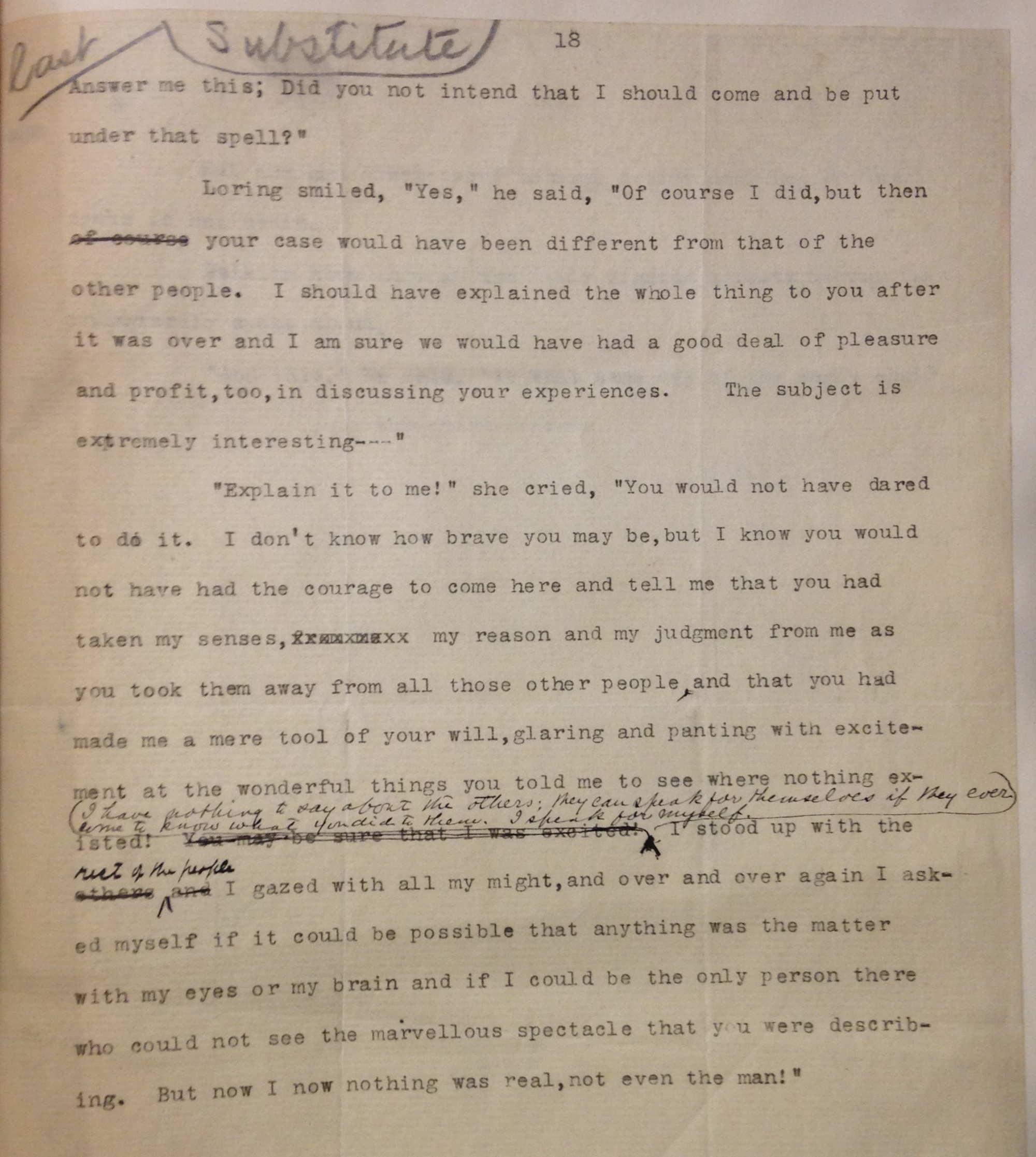

UVa’s papyrus fragment was purchased at the March 19, 2015 public auction (lot 71) of Swann Galleries, a major New York auction house. The lot description offered no provenance information, nor (as is common in the auction trade) was the consignor identified. When the papyrus was unpacked at U.Va. on May 7, I saw on the glass mount, sealed with a distinctive “papyrus”-patterned tape, an identification label with the handwritten notation “M30305/2.” Neither feature had been visible in the cropped image accompanying the lot description. Was this a collection inventory number, or, more likely, a dealer or auction house number? I have since done what I should have done initially, prior to bidding, and that is to contact the auction gallery for all documentation the gallery and the consignor may have on the papyrus’s ownership over the last several decades. Swann Galleries has confirmed that the label bears its “internal cataloguing number.” Swann has also requested documentation from the consignor, “a dealer with whom we have done business on a number of occasions,” and we are awaiting a response.

So far my other efforts to trace this fragment to a known collection, to a previous auction or trade sale, or to other pieces have been fruitless. If readers have any knowledge of other papyrus documents in mounts sealed with the same tape (visible in the attached images), I would be grateful to hear from you.

Provenance is no small matter, for we want to avoid acquiring, whether through purchase or gift, collection items for which we do not have clear title. The matter is a complicated one, for we obtain a wide chronological and geographical range of materials, in a variety of formats, from many different sources. In the case of antiquities (and certain categories of books and manuscripts), provenance is paramount, for many countries now require a license for the export of such objects, or for export after a specified date from their country of origin.

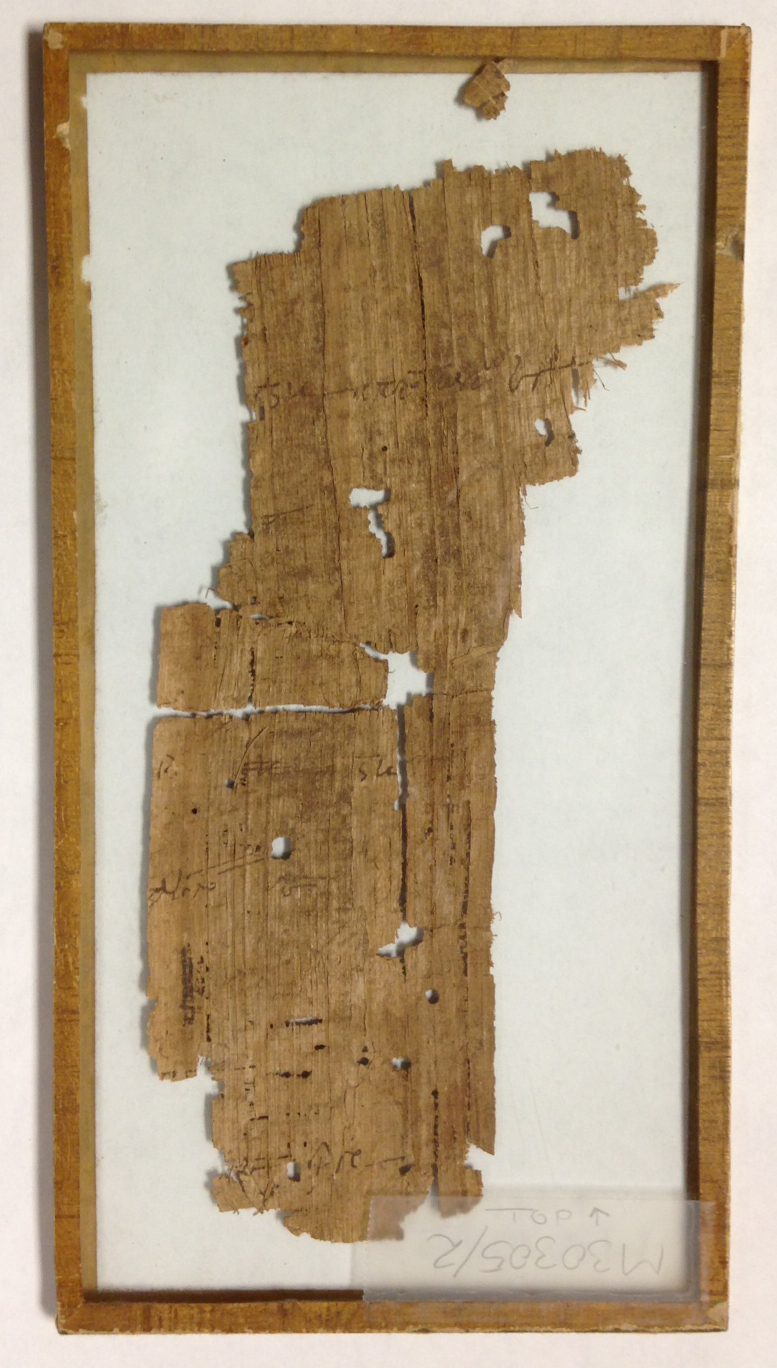

The verso of P. Virginia 1 clearly shows the vertical papyrus strips which form the document’s secondary layer. Additional lines of Greek text–perhaps docketing, or unrelated manuscript notes–are also visible.

For papyrus documents of Egyptian origin, the primary statute is Egypt’s 1983 law on the protection of antiquities, which henceforth prohibited their export without a proper license. Many, of course, were exported before the law took effect. What if we cannot trace the document’s ownership prior to 1983? That would neither prove nor disprove that the papyrus was properly exported. Here, however, assuming proper export in the absence of contrary evidence is not sufficient, for ethically we would want assurance that U.Va. was not supporting, in even the smallest way, the illegal antiquities trade.

The situation could have been avoided, of course, had I sought provenance information prior to bidding; if the document’s history could not be verified earlier than 1983, there would be no point in bidding. To my regret, I did not. I am deeply indebted to the readers who have enlightened me by sharing information on what is apparently an active, illegal market in papyrus manuscripts, online and elsewhere, conducted by dealers outside the established antiquities and manuscripts trade channels. Accounts such as those posted by Brice Jones and Dorothy King present a disturbing picture of this market, which is likely replenished by continuing illegal exports and supported by buyers who neither demand full documentation, nor convey it to the next owner. Often the provenance information supplied is either insufficient or dubious.

It may take some time to complete our investigation into the document’s provenance and then settle on a course of action. Readers will receive an update in a future blog post.

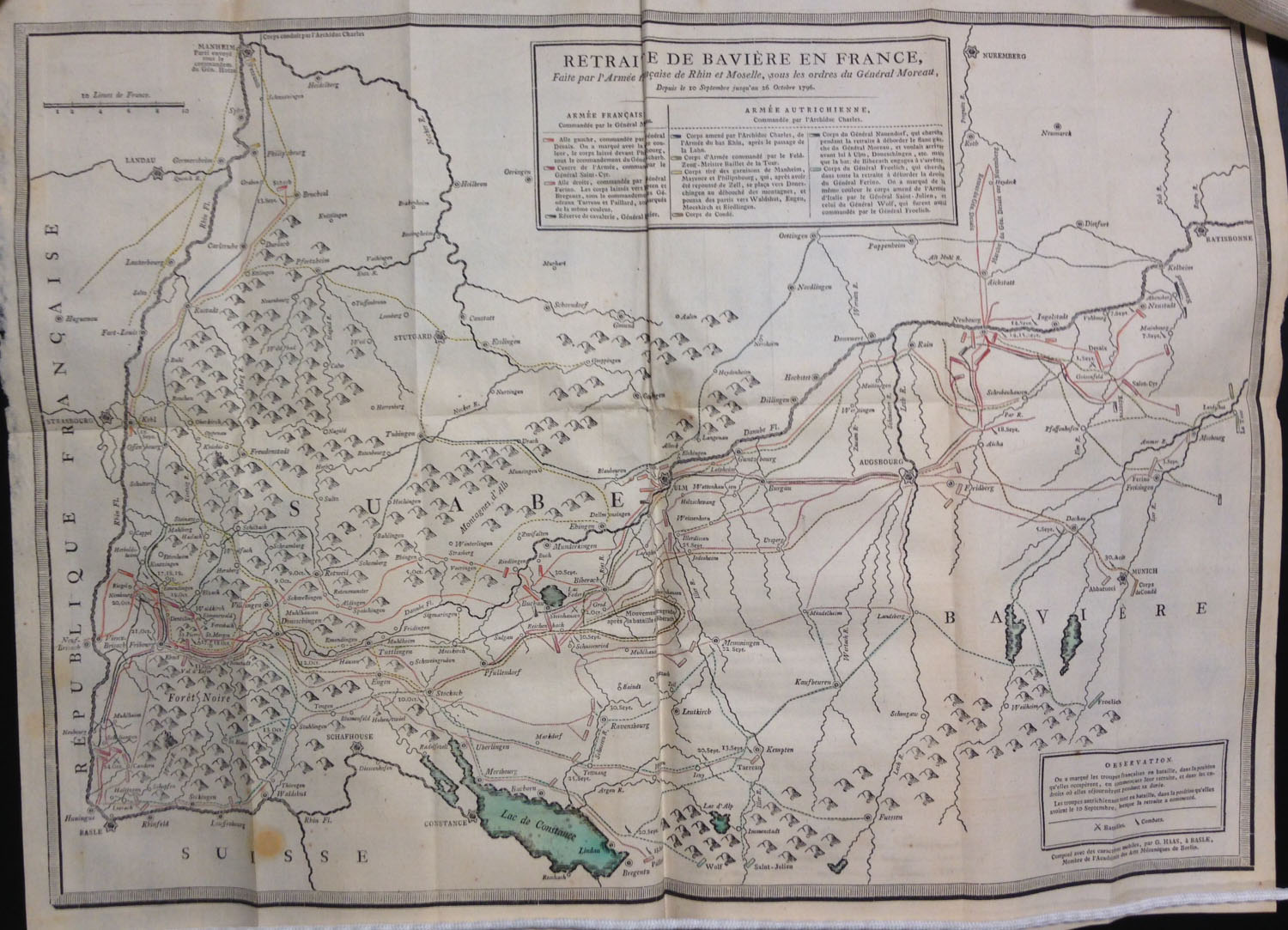

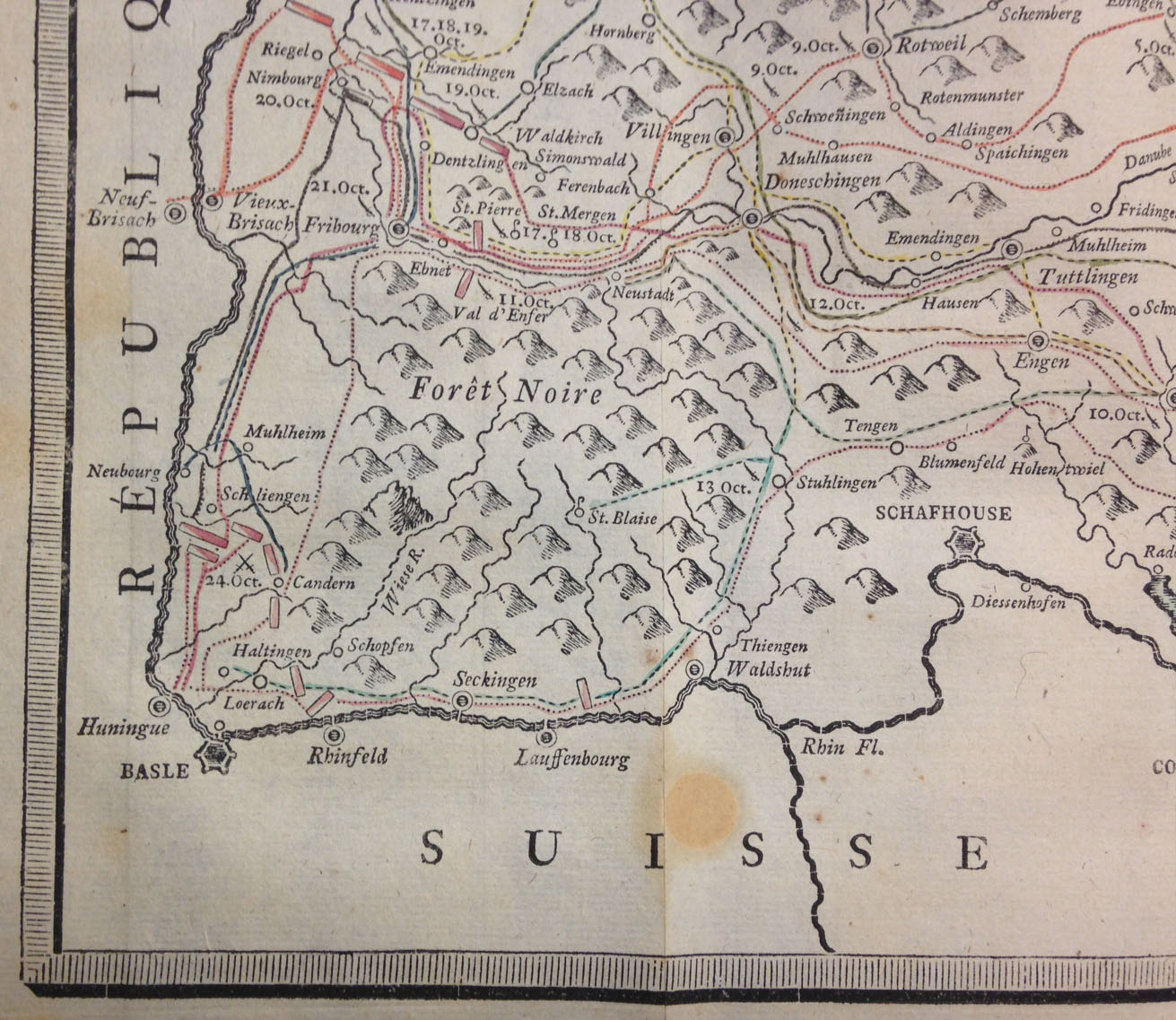

![The map, "composed with movable types," bears the imprint of G[uillaume, i.e. Wilhelm] Haas, the Basel [Switzerland] typefounder who cut and cast the special cartographic font.](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Map2.jpg)

![Public lands in Illinois: January 17, 1839 ... [Vandalia, Ill., 1839] (A 1839 .I55)](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/MG1.jpg)

![Augustus Q. Walton [i.e. Virgil Stewart], A history of the detection, conviction, life and designs of John A. Murel ... (New York, 1839) (A 1839 .W26)](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/MG2.jpg)

![The grant of the Venezuelian Emigration Company, with full explanation of their laudable object ... [St. Louis?, 1866] (A 1866 .G73)](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/MG4.jpg)

![Engraved reproduction of the famous Dove Mosaic discovered by Giuseppe Alessandro Furietti at Hadrian's Villa and now in Rome's Capitoline Museum. Furietti believed it to be the actual mosaic created by Sosus for the royal palace at Pergamon, as described by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History. Giuseppe Alessandro Furietti, De musivis (Rome, 1752), plate [1]. (NA3750 .F8 1752)](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/X1.jpg)

![Two stages in the creation of a lithographic image, from Alphonse Chevallier, Mémoire sur l’art du lithographe (Paris, [1829]) (NE2420 .C54 1829)](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/B5.jpg)