Every autumn the U.Va. Library hosts the annual Tracy W. and Katherine W. McGregor Distinguished Lecture in American History. This year the speaker was Edward L. Ayers, President of the University of Richmond and formerly professor of history at U.Va., who on October 28 delivered a brilliant talk on “The Shape of the American Civil War.” October is also the month during which we compile a listing of books and manuscripts added over the past year to the Tracy W. McGregor Library of American History. Here are a few highlights.

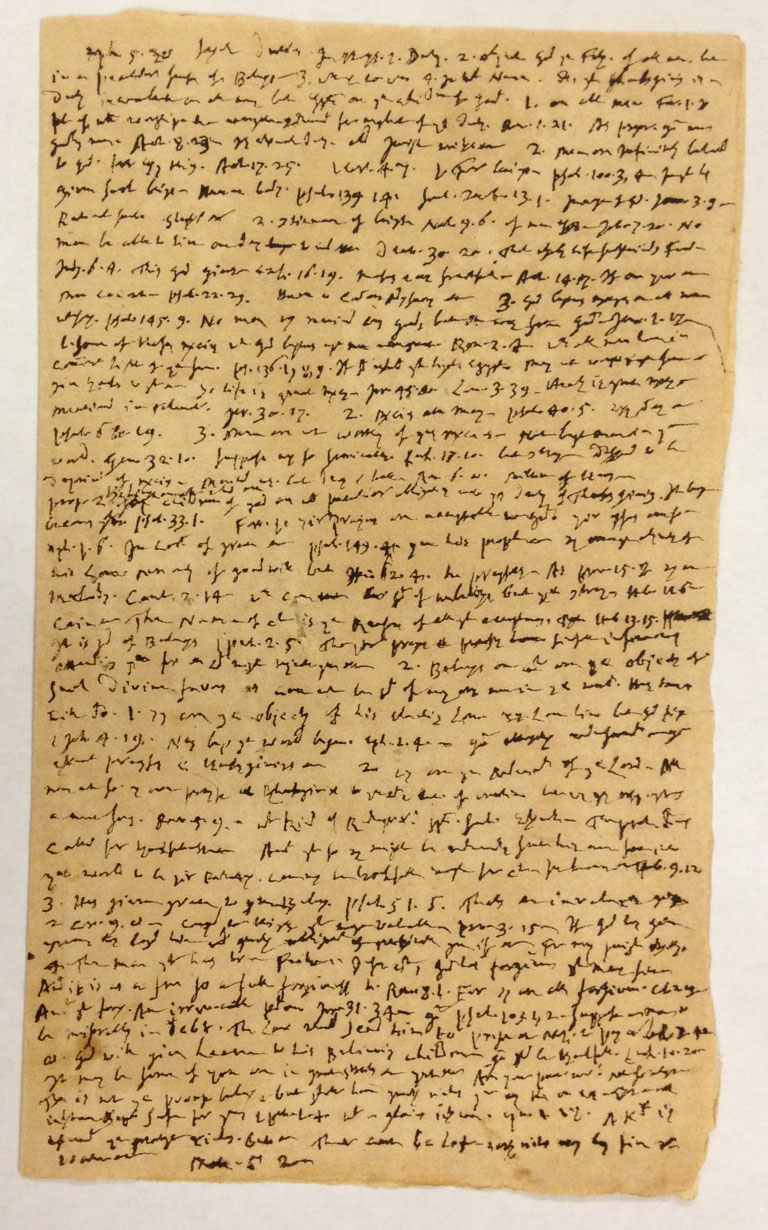

Manuscripts by the Puritan minister Increase Mather are of great rarity, hence we were delighted to acquire these notes for a sermon, “Thanksgiving throughout ye province,” delivered in Boston on December 2, 1718. Written when Mather was 79, these notes confirm contemporary accounts of his working methods. After decades of experience, Mather no longer needed to write out sermons in full; rather, he preached from memory after sketching out sermons in notes such as these, which he carried to the pulpit as a memory aid. What makes this acquisition even more special is that it had once resided in the celebrated Mather collection formed by a descendant, William G. Mather. When Tracy McGregor purchased Mather’s collection in 1935, he permitted Mather to retain a few items, including this manuscript. Now that it was once again available, we promptly reunited it with the Mather Collection after, coincidentally, a 79-year absence.

Woodcut of a Sioux Indian “queen” from Der Reisen der Capitaine Lewis und Clarke … (Lebanon, Pa., 1811) (A 1811 .T73)

Perhaps the year’s most gratifying acquisition has been Die Reisen der Capitaine Lewis und Clarke, which had long been on our desiderata list. Given that Meriwether Lewis and Thomas Jefferson both had deep Charlottesville roots, we have long been interested in the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Thanks to the McGregor Library, U.Va. has a superb collection of primary printed sources relating to the expedition. The only significant lacuna was this very rare work—a gap now filled. Lewis and Clark returned home in 1806, but publication of the official expedition report was delayed until 1814. Meanwhile the public’s intense interest in the expedition and what it found out west was whetted piecemeal by expedition participants’s published memoirs, newspaper articles, and the like. In 1809 an unauthorized account, culled from published sources, was issued in Philadelphia under the title, The Travels of Capts. Lewis & Clarke. Two years later this abridged German translation helped spread news of the expedition to the Mid-Atlantic’s substantial German-American population. Included are four full-page woodcut Indian portraits copied from the Philadelphia edition.

This unprepossessing (and very rare) three-page Illinois state document, Public lands in Illinois: January 17, 1839, might not seem of much interest. However, it takes pride of place as item #1 in the standard bibliography of Abraham Lincoln’s writings, being his first separate publication. Then a 29-year-old Illinois state legislator, Lincoln urges that Illinois borrow $5 million to purchase the 20 million acres of state land then held by the federal government. Income from land sales would fund the state’s ambitious program of public works while simultaneously paying off the loan. The resolution was approved, but Illinois’s senators and congressmen were unable to secure passage in Congress of the requisite federal law.

![Augustus Q. Walton [i.e. Virgil Stewart], A history of the detection, conviction, life and designs of John A. Murel ... (New York, 1839) (A 1839 .W26)](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/MG2.jpg)

Augustus Q. Walton [i.e. Virgil Stewart], A history of the detection, conviction, life and designs of John A. Murel … (New York, 1839) (A 1839 .W26)

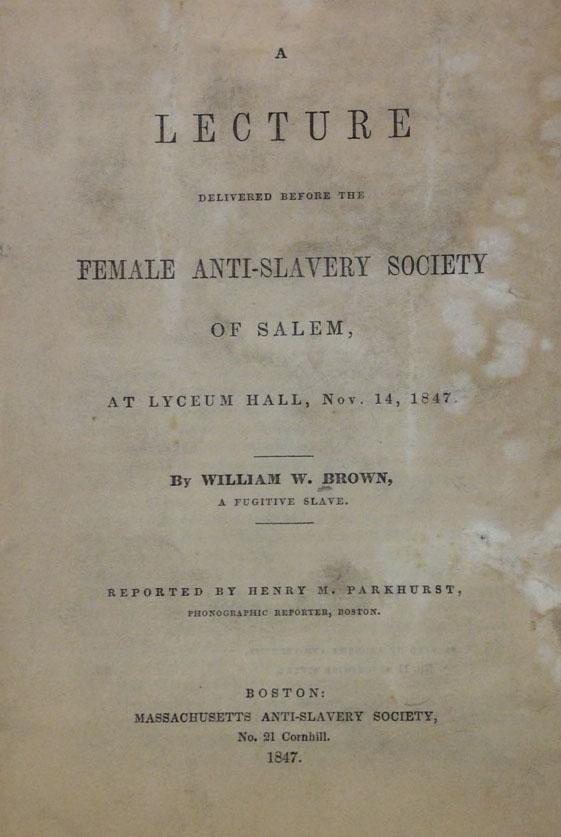

William Wells Brown, A lecture delivered before the Female Anti-Slavery Society of Salem … Nov. 14, 1847 … (Boston, 1847) (A 1847 .B74)

A lecture delivered before the Female Anti-Slavery Society of Salem at Lyceum Hall, Nov. 14, 1847 is the second published work by William Wells Brown, one of the most prominent African Americans of the 19th century (and the subject of a newly published biography). Born into slavery in 1814, Brown escaped to Ohio in 1834 and soon joined the abolitionist movement. In 1847, shortly before delivering this impassioned lecture, Brown published an autobiography, which for a time made him as prominent a figure in abolitionist circles as Frederick Douglass. Brown was in England when the Fugitive Slave Act was passed in 1850, and he remained abroad rather than return and risk capture. There, in 1853, he published what is considered the first novel written by an African American, Clotel. Brown eventually returned to Boston, where he was prominent in its African American community and published several more books.

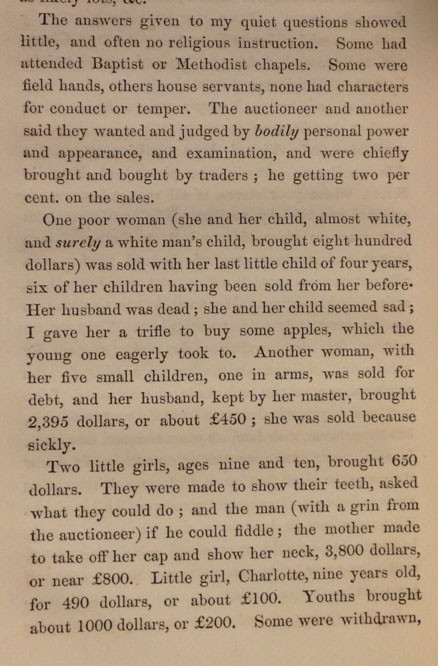

Robert A. Slaney’s account of a Richmond, Va. slave auction, from his Short journal of a visit to Canada and the states of America, in 1860 (London, 1861) (A 1861 .S53)

A new addition to the McGregor Library’s comprehensive collection of American travel narratives is this fascinating and candid diary kept by Robert A. Slaney, a member of Parliament, while traveling in the entourage of the 18-year-old Prince of Wales during his 1860 American tour. From Boston the prince traveled to Niagara and then to Detroit, where Slaney found the residents to be “all pale, none fat. How is this? … Detroit is laid out with noble, wide streets … there are many nice villas, as of retired or rich persons, in and about this flourishing town.” In Chicago they witnessed a torchlight procession supporting Abraham Lincoln’s presidential bid. From St. Louis the party journeyed overland by train to Washington, DC, which they explored at length. President Buchanan’s White House reception for the prince was somewhat disappointing: “No refreshments but two large bowls of punch.” Perhaps of greatest interest is Slaney’s disapproving account of the slave auctions he witnessed in Richmond, Va., which reflects his liberal leanings. Indeed, this rare work was one of the first printed at the Victoria Press, established by English women’s rights advocate Emily Faithfull and entirely staffed by women.

![The grant of the Venezuelian Emigration Company, with full explanation of their laudable object ... [St. Louis?, 1866] (A 1866 .G73)](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/MG4.jpg)

The grant of the Venezuelian Emigration Company, with full explanation of their laudable object … [St. Louis?, 1866] (A 1866 .G73)

![Public lands in Illinois: January 17, 1839 ... [Vandalia, Ill., 1839] (A 1839 .I55)](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/MG1.jpg)