This week we are pleased to feature a post from Nora Benedict, who will receive a Ph.D. in Spanish this Saturday. Nora’s research for her dissertation, “The Fashioning of Jorge Luis Borges: Magazines, Books, and Print Culture in Argentina (1930-1951),” serves as the inspiration for her exhibition in our First Floor Gallery, open through July 7, 2017.

Nora has been a constant presence here in Special Collections for many years as a researcher, a Bibliographical Society Fellow, a Rare Book School staff member tasked with working in our stacks to prepare materials for classes, and as a graduate assistant to staff member Heather Riser. Thanks, Nora, for all you’ve done for the library–and for providing us with your blog entry in two languages! (To read Nora’s post in English, scroll to the end of the Spanish version.)

Borges, libros y bibliografía

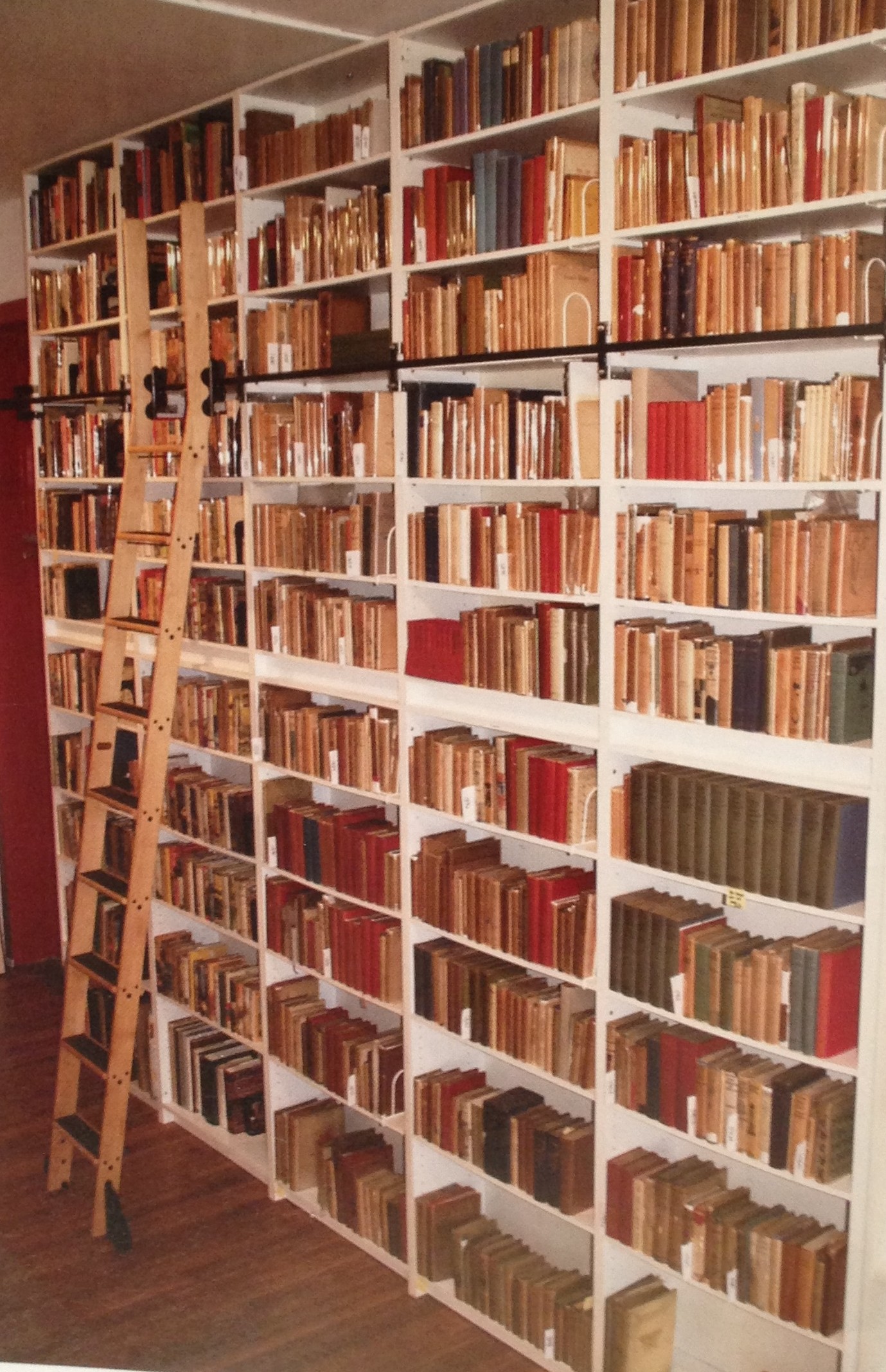

Casi tres cuartos de siglo después de la primera publicación de sus laberintos vertiginosos y bibliotecas sin límites en Ficciones, Jorge Luis Borges y sus libros siguen despertando el interés de ambos investigadores y aficionados. Como la mayoría de las personas que pasan por la Universidad de Virginia, descubrí su Borges Collection por casualidad. Aparte de la experiencia inverosímil de tocar e hojear los manuscritos y cartas escritos por Borges mismo, lo que más me llamó la atención de la colección en sí es el nivel de completitud. Desde un punto de vista bibliográfico, todo lo que hay en la colección sirve, de manera ideal, para cualquier tipo de investigación textual. Además de los manuscritos valiosos y periódicos raros, hay por lo menos una copia de cada edición de cada libro que Borges publicó durante su vida (¡en algunos casos hay más de una copia de ciertas obras que son aún más raras que los manuscritos!). En cierto sentido, es el lugar perfecto para estudiar la evolución de su proceso de escribir desde los manuscritos hasta las primeras y posteriores ediciones.

Dado que he pasado la mayor parte de cinco años estudiando todo el contenido de la colección, siempre me encanta hablar de los tesoros maravillosos que se pueden encontrar aquí, lo cual generalmente lleva a varias personas a preguntarme cómo estas cosas llegaron a la Universidad de Virginia. Me pregunté eso también cuando vi, por primera vez, los manuscritos originales de Fervor de Buenos Aires, copias prístinas de la revista mural Prisma y dibujos impresionantes en la mano distinta de Borges. Dicho eso, de pronto aprendí que la presencia de esta colección en la Universidad de Virginia tiene sentido por varias razones. En primer lugar es su vínculo con la fortaleza sobresaliente de las colecciones especiales de la universidad: la historia y literatura americana. Sin lugar a dudas, no se debe restringir esta categoría a las obras norteamericanas, sino hay que extenderla lógicamente a la producción cultural de todas las Américas. Junto a esta conexión bien clara, también veo la historia de la bibliografía en la Universidad de Virginia y el estudio del libro como objeto como elementos esenciales para entender la decisión de incluir a estos materiales en las colecciones de Virginia a causa de que se puede seguir e identificar cualquier cambio textual dentro de una obra (ya sea verbal o la presentación física de un texto).

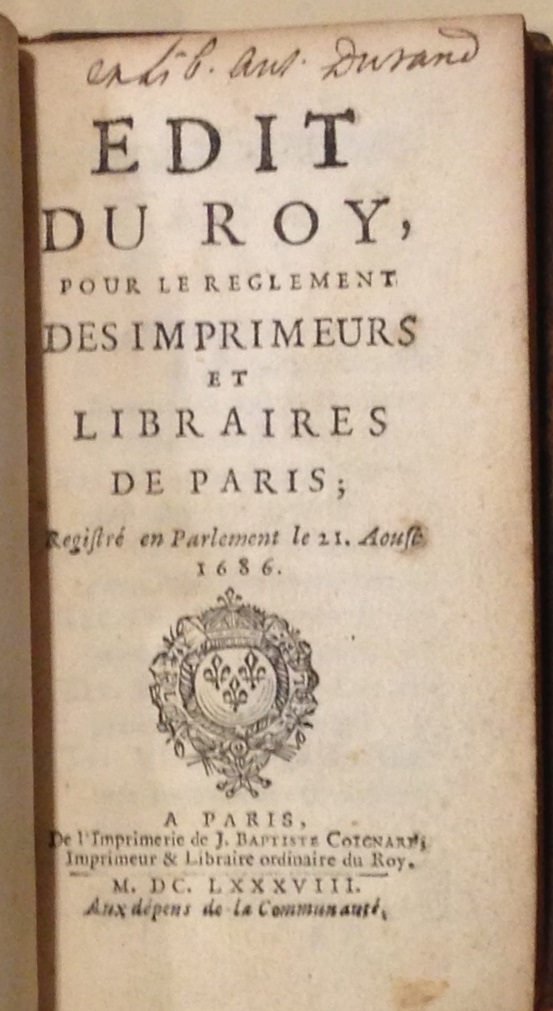

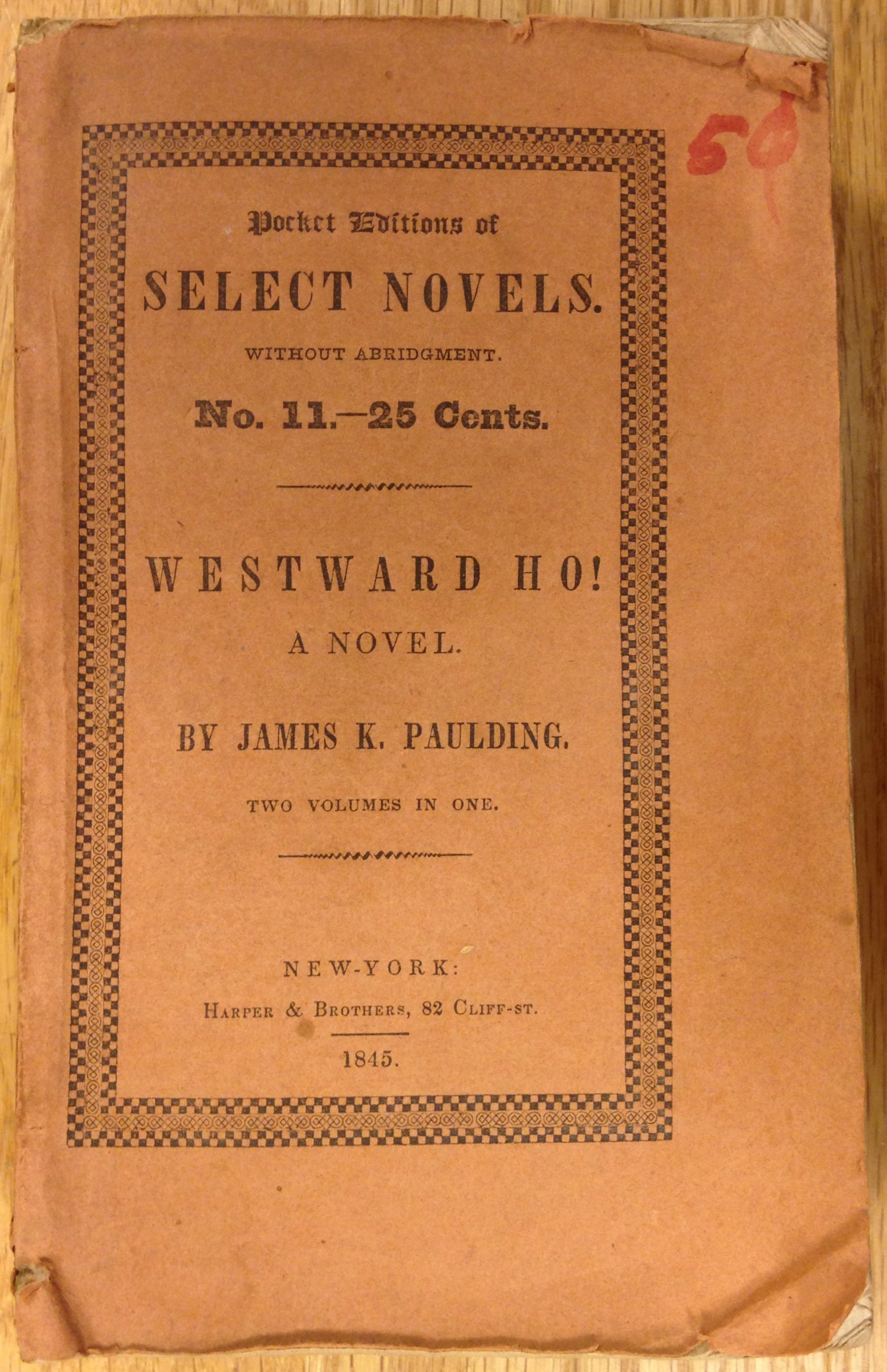

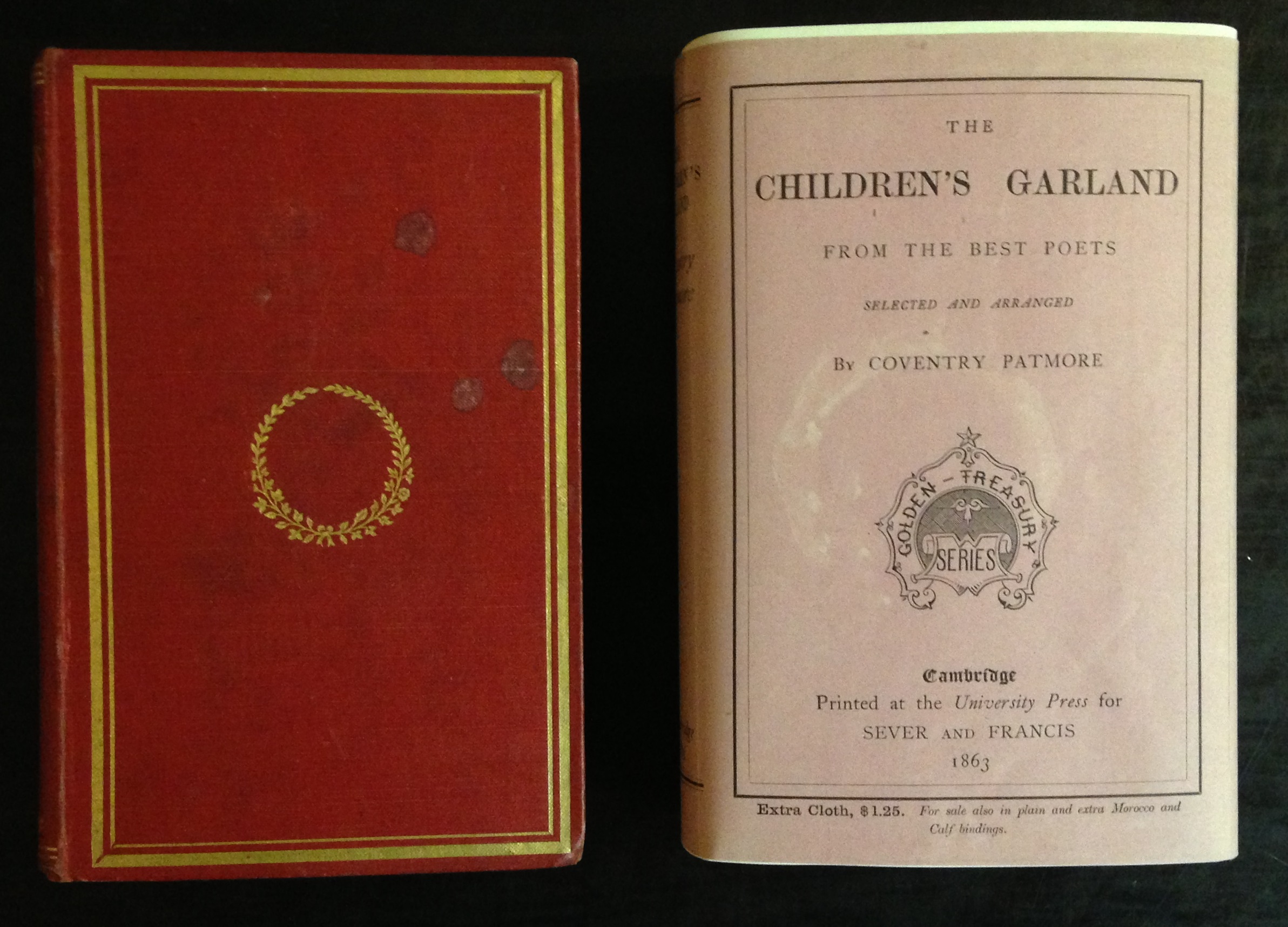

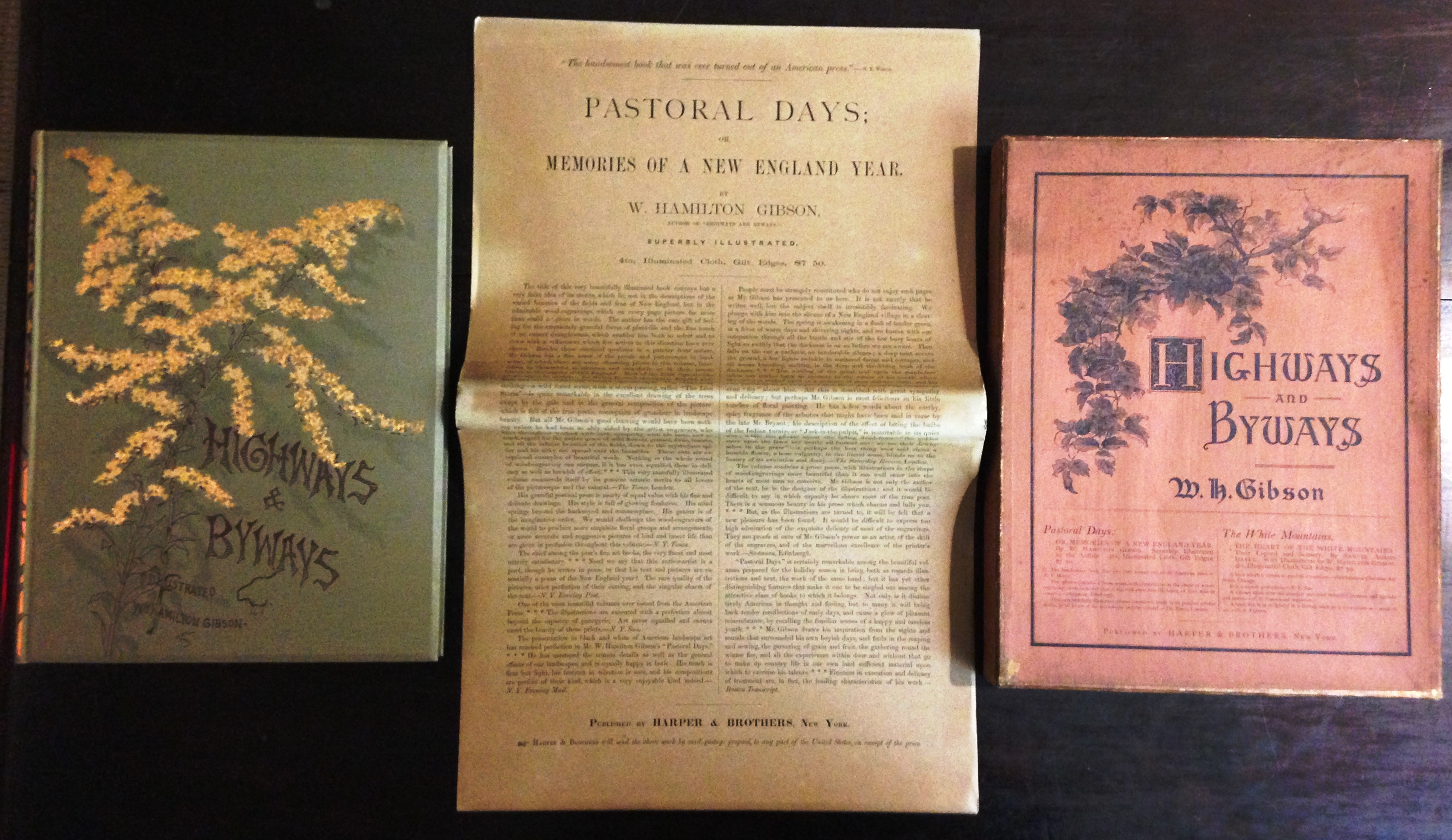

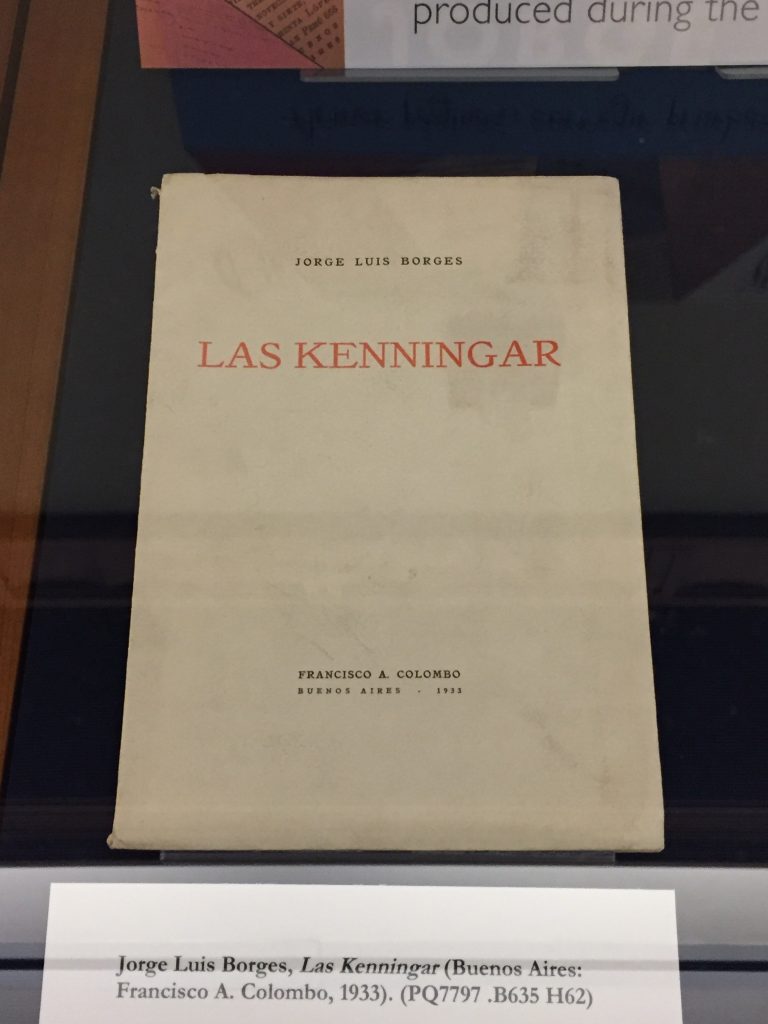

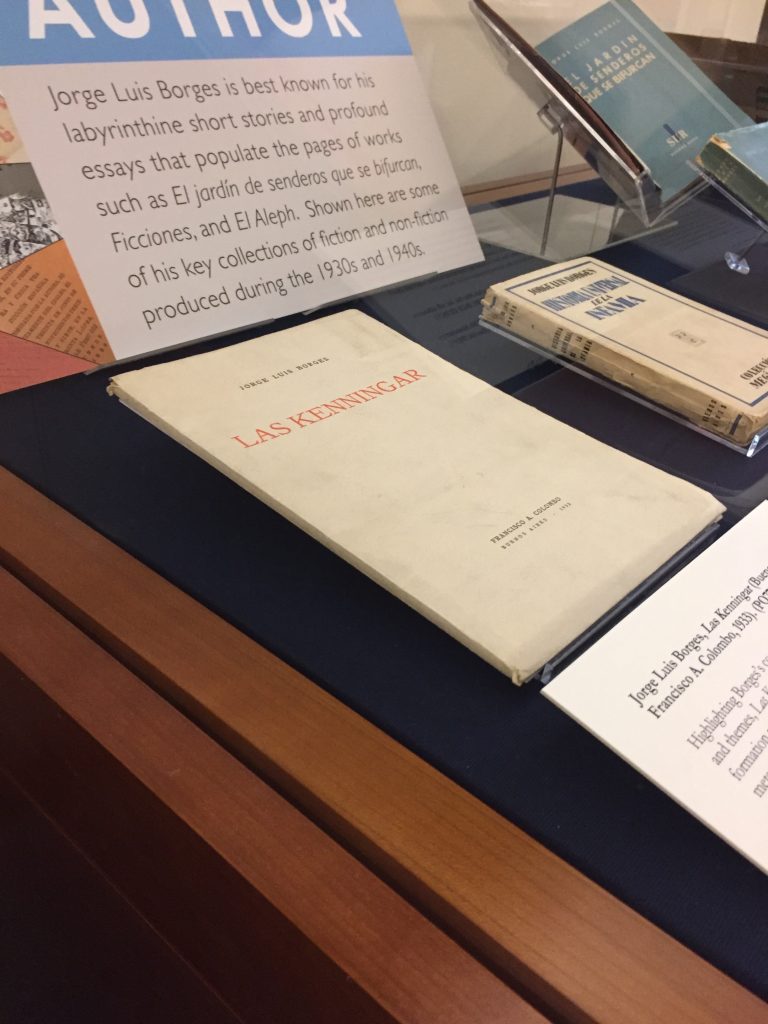

“Las Kenningar” se publicó por primera vez en una revista literaria. Borges lo imprimió de nuevo unos años más tarde con Francisco A. Colombo, un impresor de lujo. (PQ7797 .B635 H62)

Mi exhibición, “‘Armar páginas, corregir pruebas’: Jorge Luis Borges as Author, Editor, and Promulgator,” recurre a las investigaciones para mi tesis doctoral sobre Borges y sus roles diversos dentro de la industria editorial en Buenos Aires. También hace hincapié en los tesoros menos conocidos de la colección en la universidad y las posibilidades para investigaciones futuras. Además de escribir prosa y poesía espléndida, a Borges le interesan los aspectos técnicos de la producción de libros, periódicos y revistas literarias. Desde un momento muy temprano en su carrera literaria estaba muy involucrado en corregir pruebas y aún armar páginas para las varias obras que escribió o editó.

Para mí lo más difícil de ser curadora de esta exhibición fue seleccionar un número limitado de cosas y crear una narrativa lógica que interesaría a expertos en Borges y, a la vez, a estudiantes que no sepan nada de él. Finalmente visualicé tres categorías vinculadas que ilustrarían cómo Borges navegó elegantemente las formas públicas y privadas de la escritura: Autor, Editor, Promulgador. Más específicamente, cada una de las cajas explora un rol distinto que Borges tenía en la industria editorial porteña durante los años 1930 y 1940 con el fin de enfatizar su impacto en los cánones literarios y los estándares educacionales. “Autor” presenta una selección de las colecciones de ficción y no ficción de Borges como Ficciones, El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan y Historia universal de la infamia.

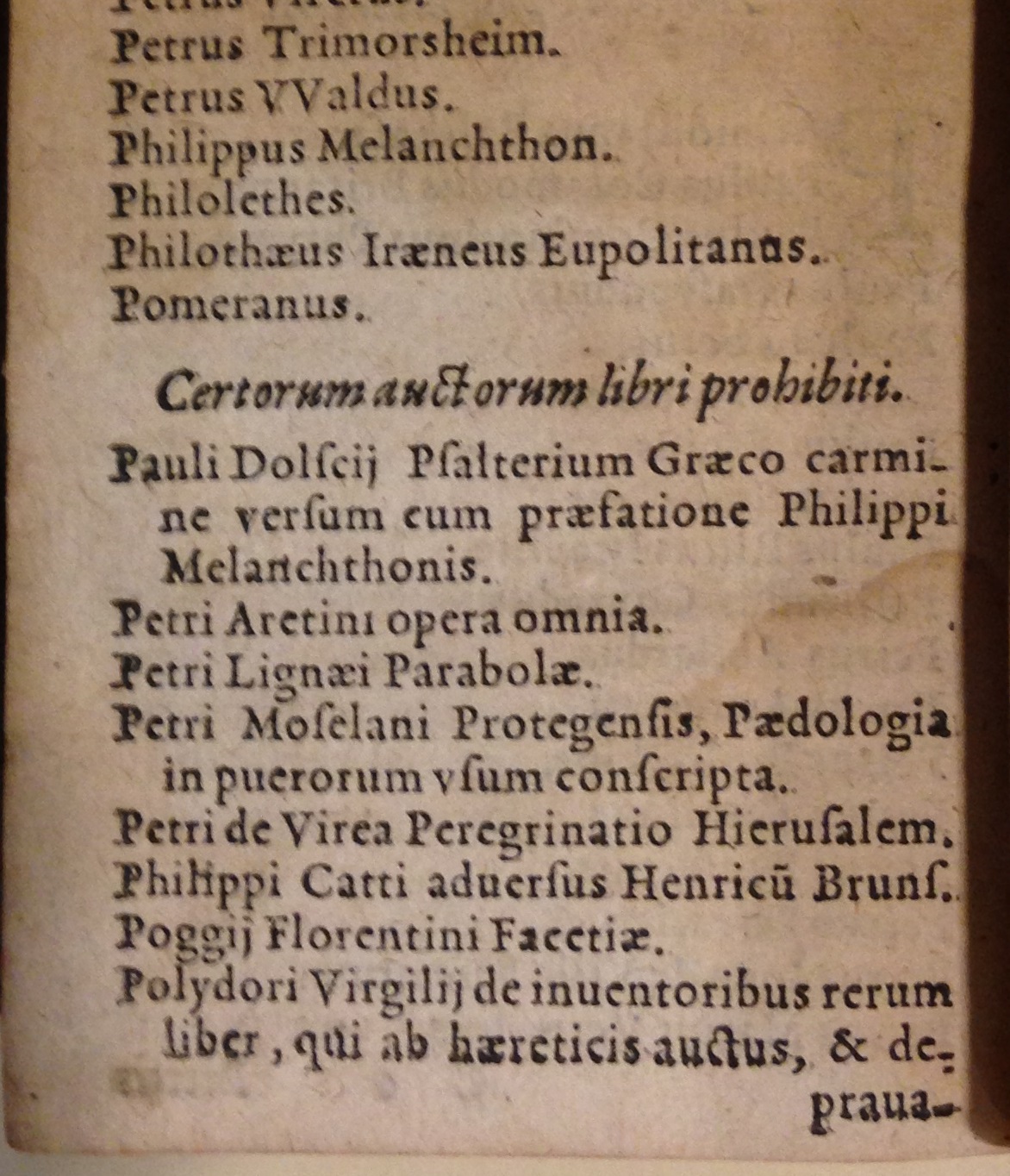

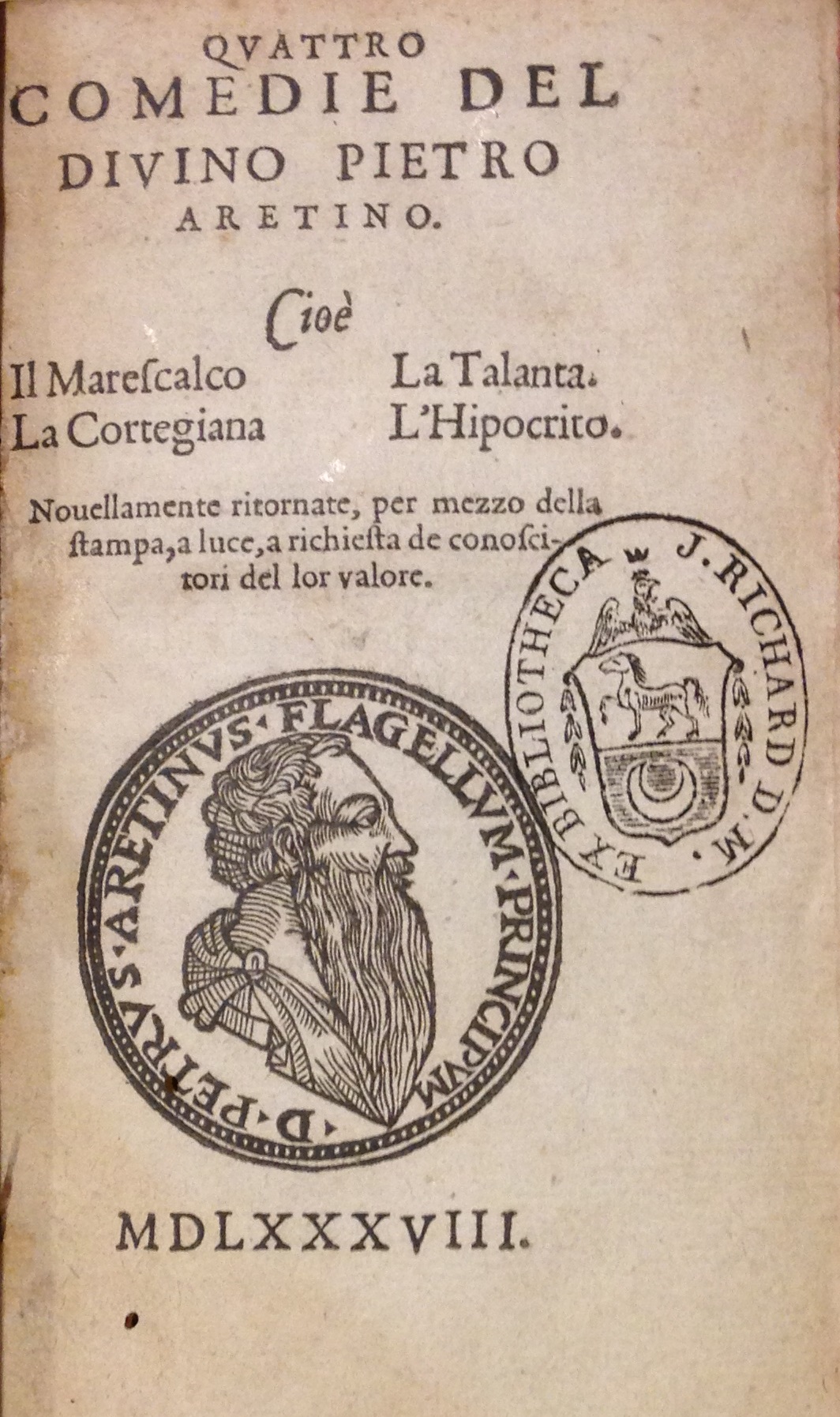

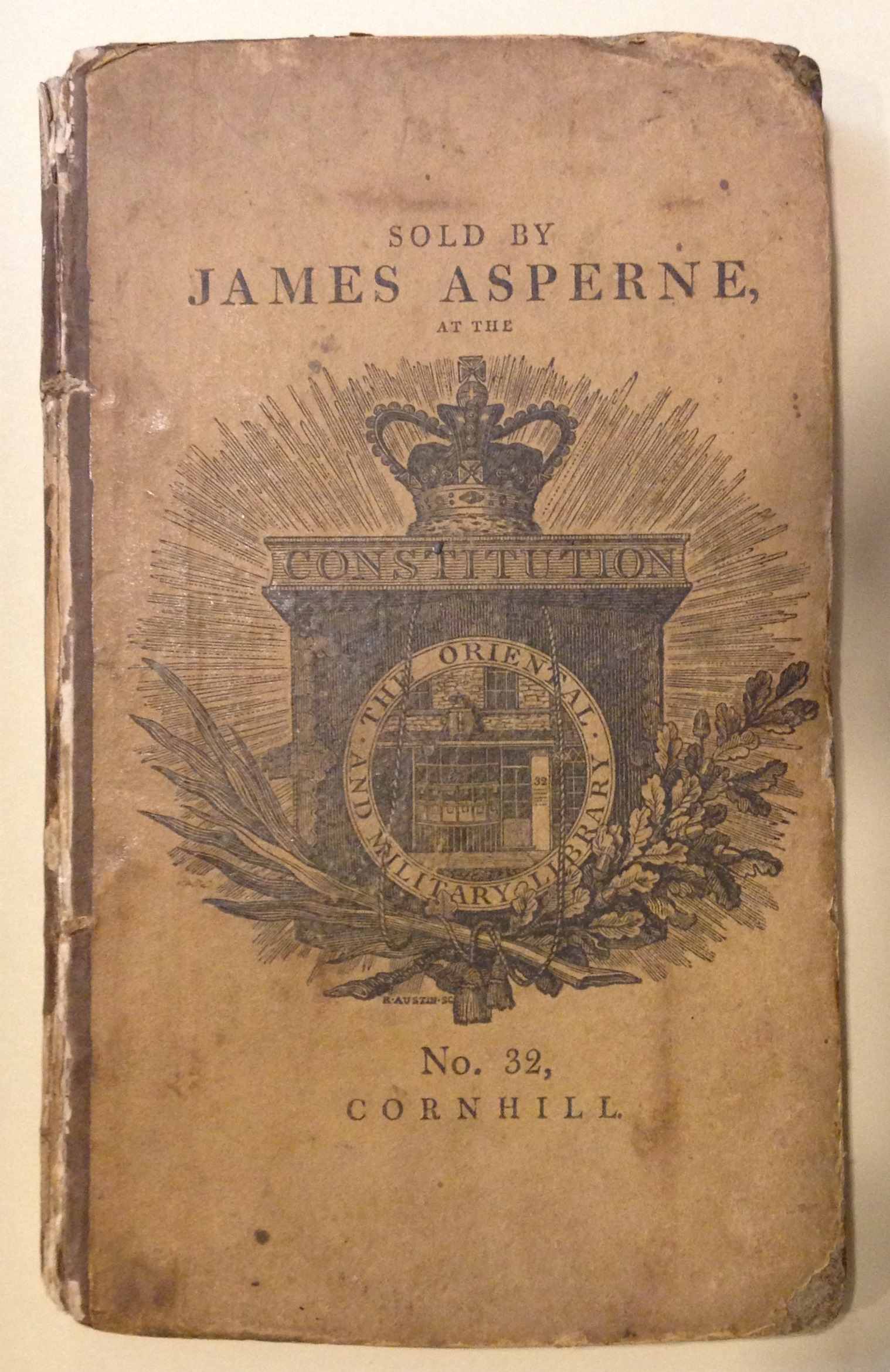

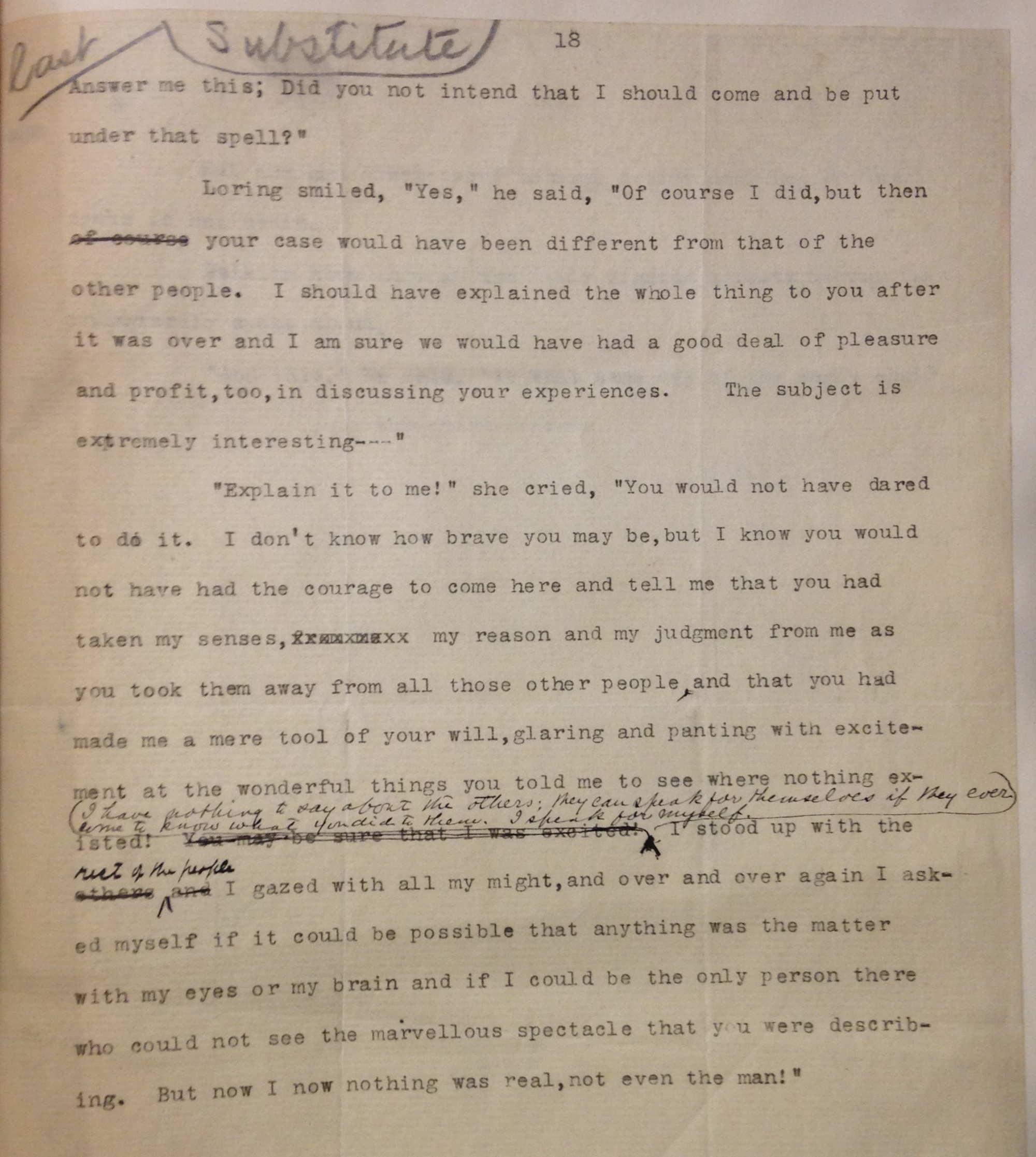

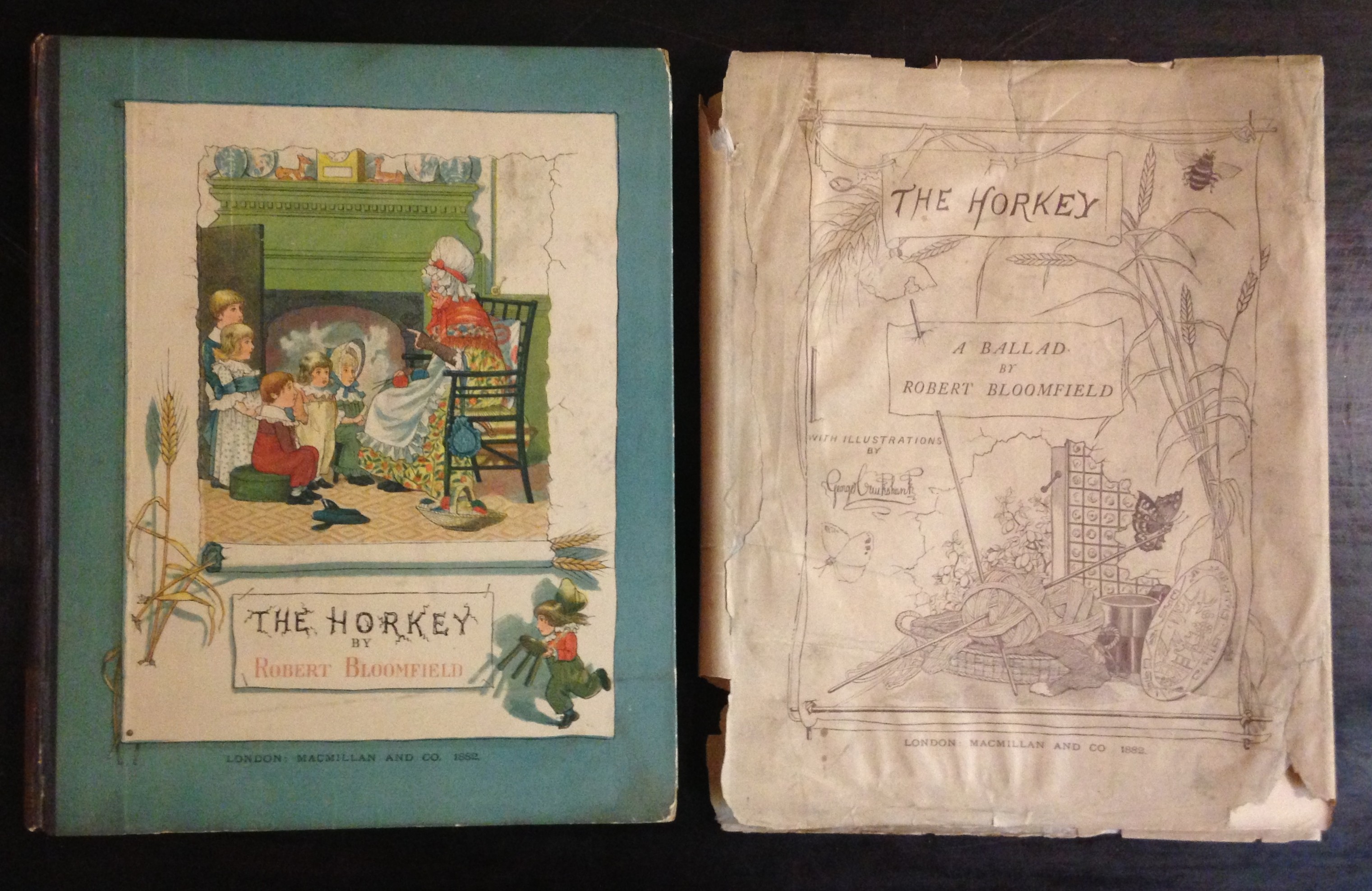

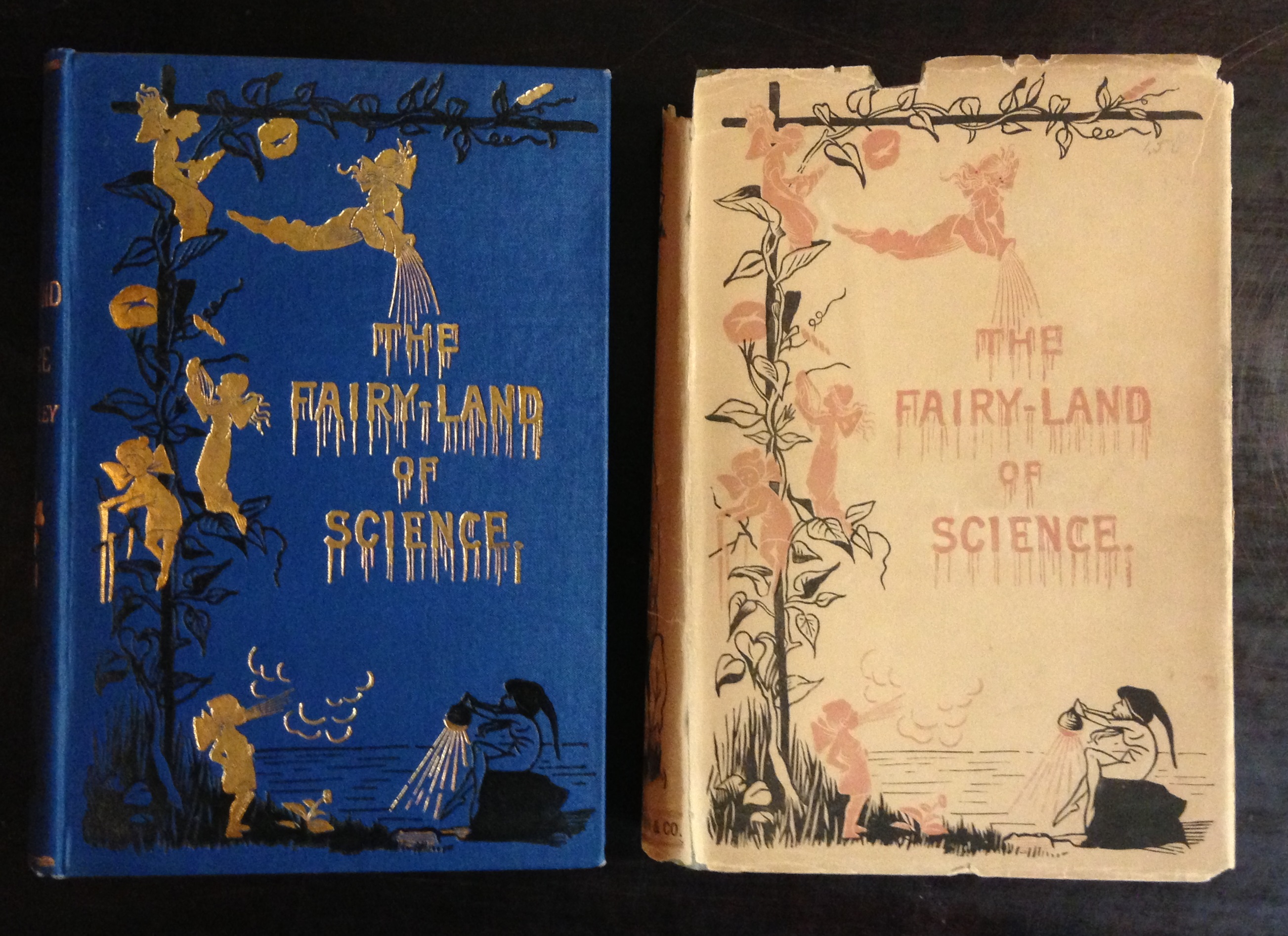

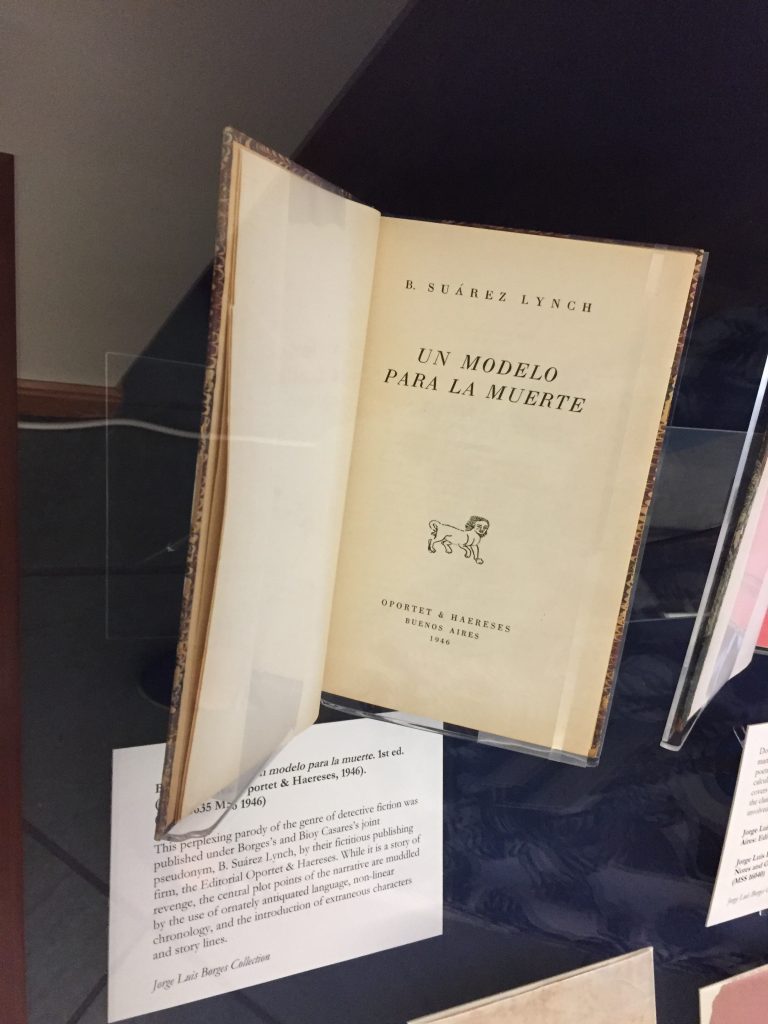

“Editor” demuestra las conexiones arraigadas que Borges tenía con la forma física del libro a través de unos ejemplos de las obras publicadas con sus dos editoriales (ficticias), la Editorial Destiempo y la Editorial Oportet & Haereses.

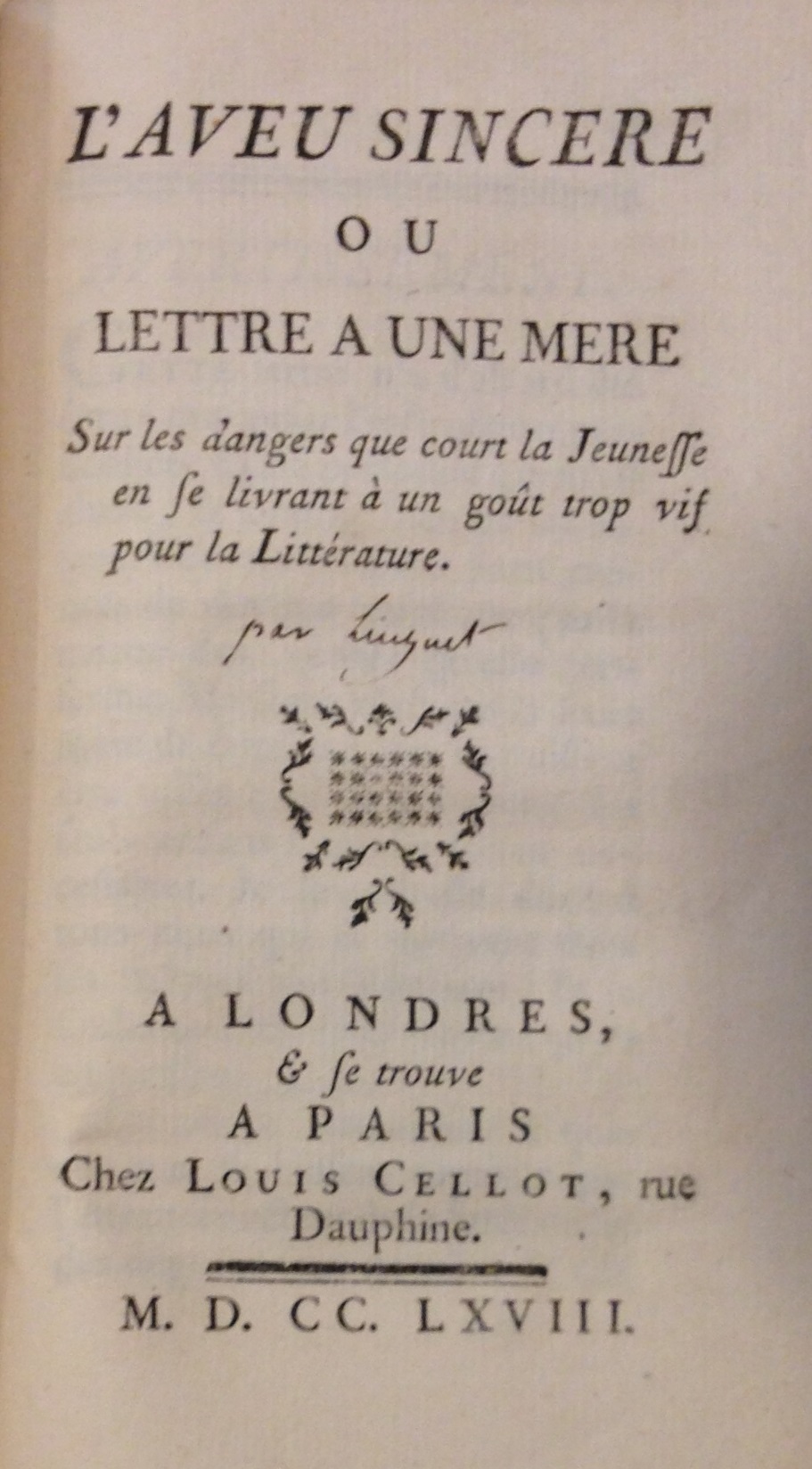

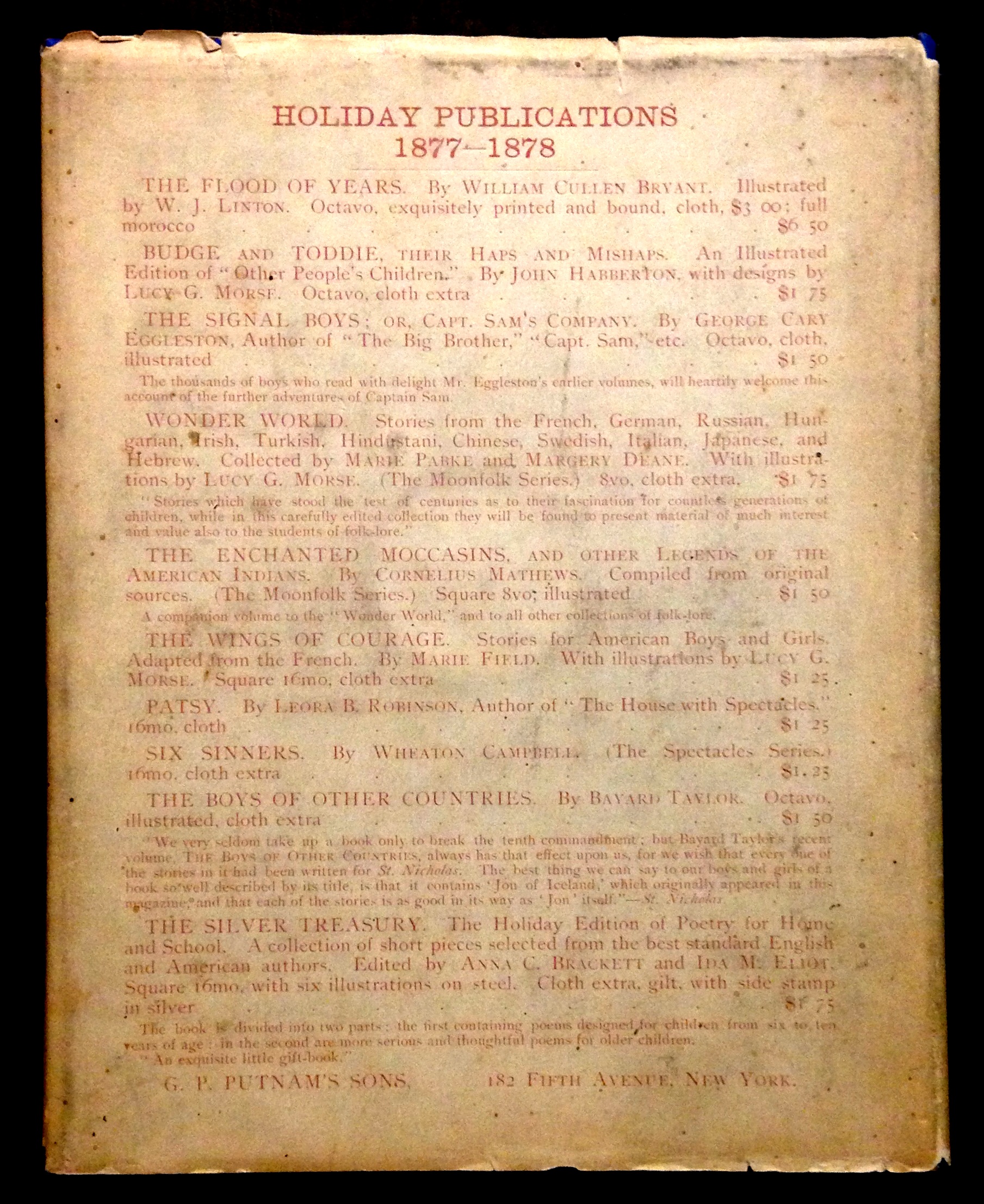

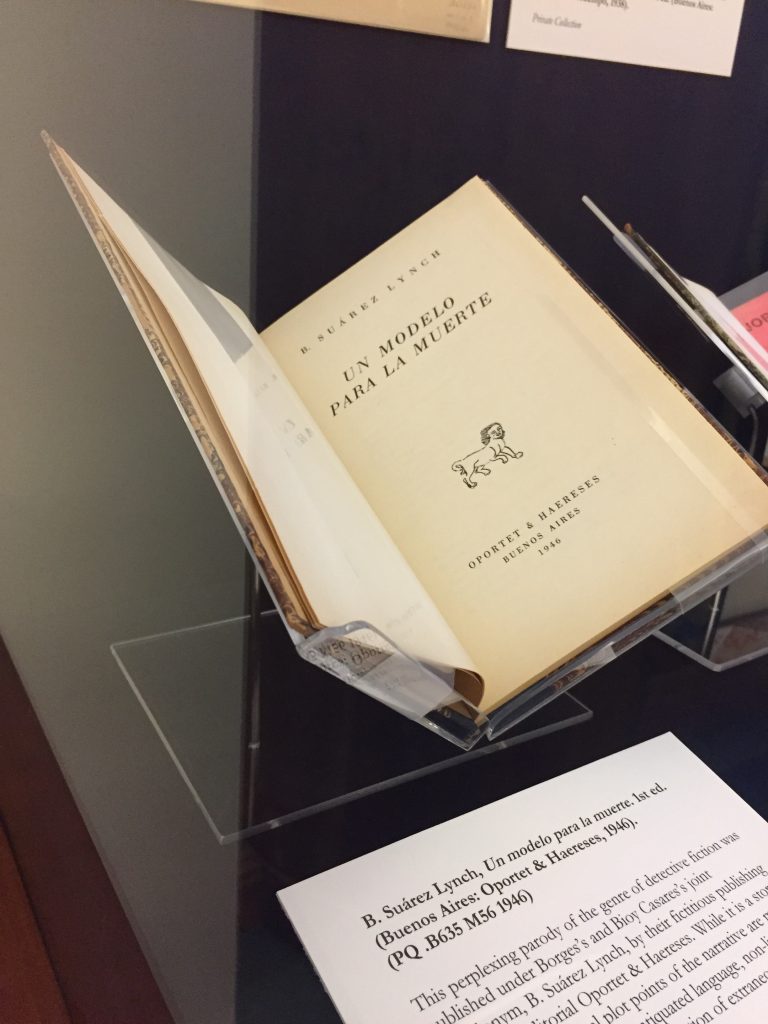

“Un modelo para la muerte,” una parodia desconcertante del género detectivesco, se publicó bajo un seudónimo de Borges y Adolfo Bioy Casares, B. Suárez Lynch, con su editorial ficticia, la Editorial Oportet & Haereses.(PQ .B635 M56 1946)

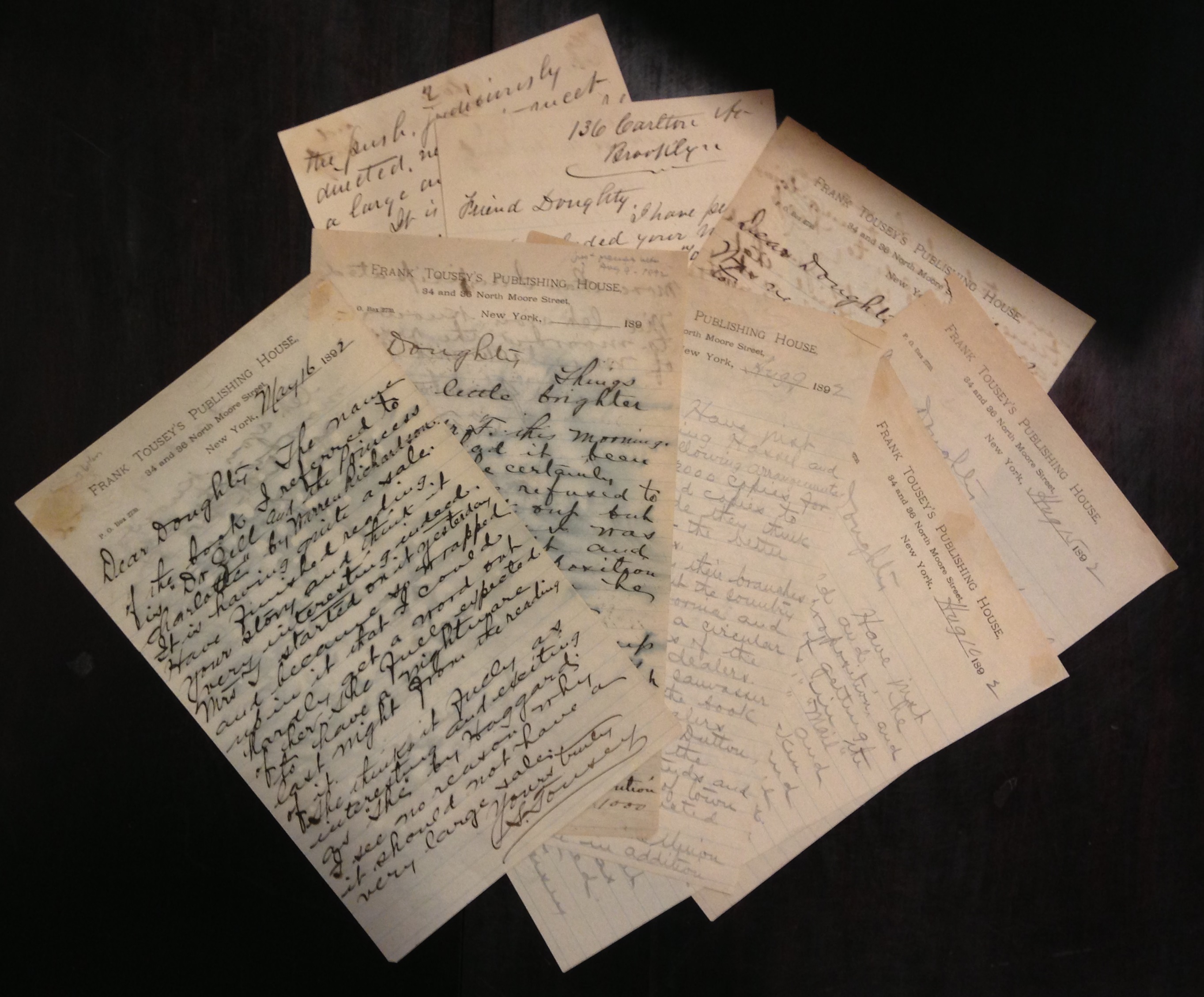

También incluí dos manuscritos originales de Borges que hacen hincapié en sus vínculos bien fuertes con otras editoriales y su trabajo frecuente de escribir prólogos para las obras de otros autores.

“Promulgador” destaca su trabajo editorial, a veces bajo cuerda, en traducir, editar y prologar para varias editoriales argentinas.

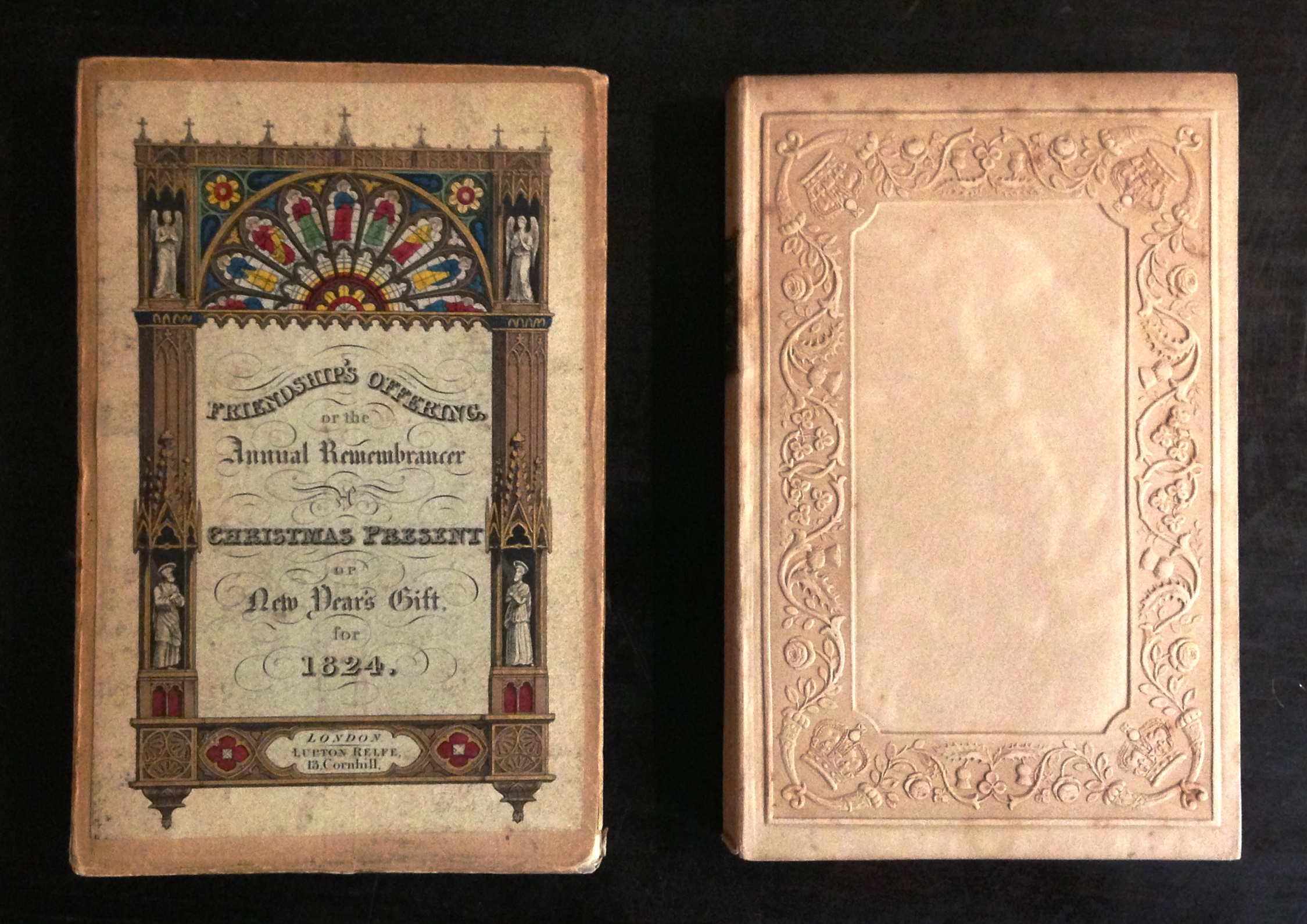

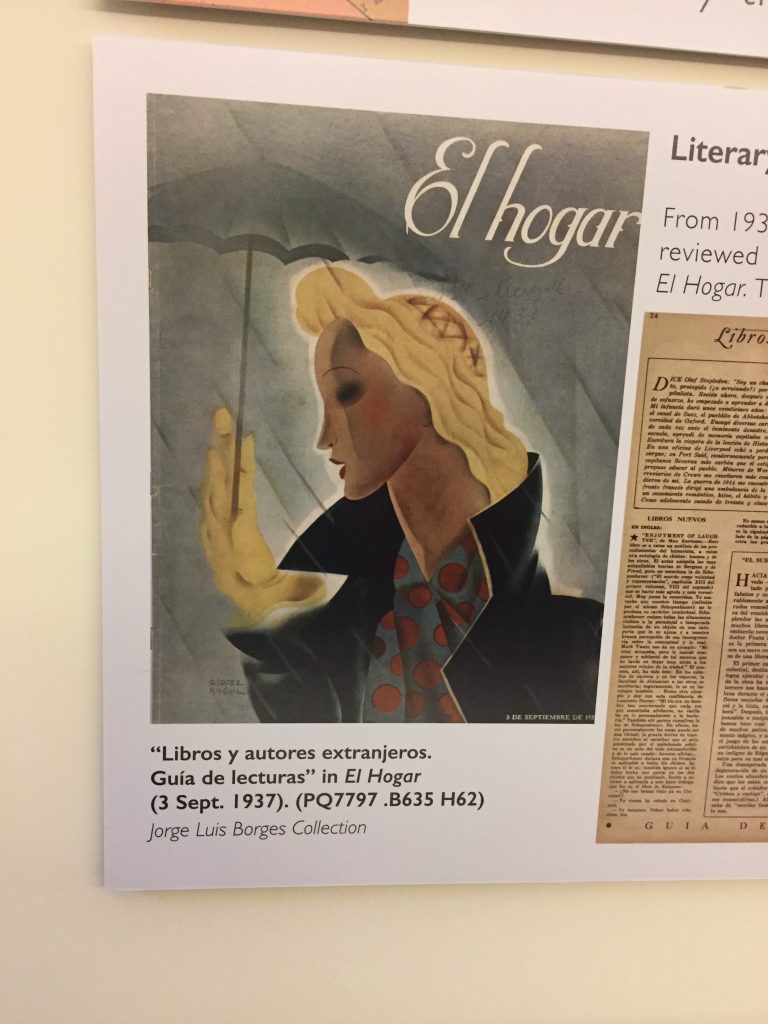

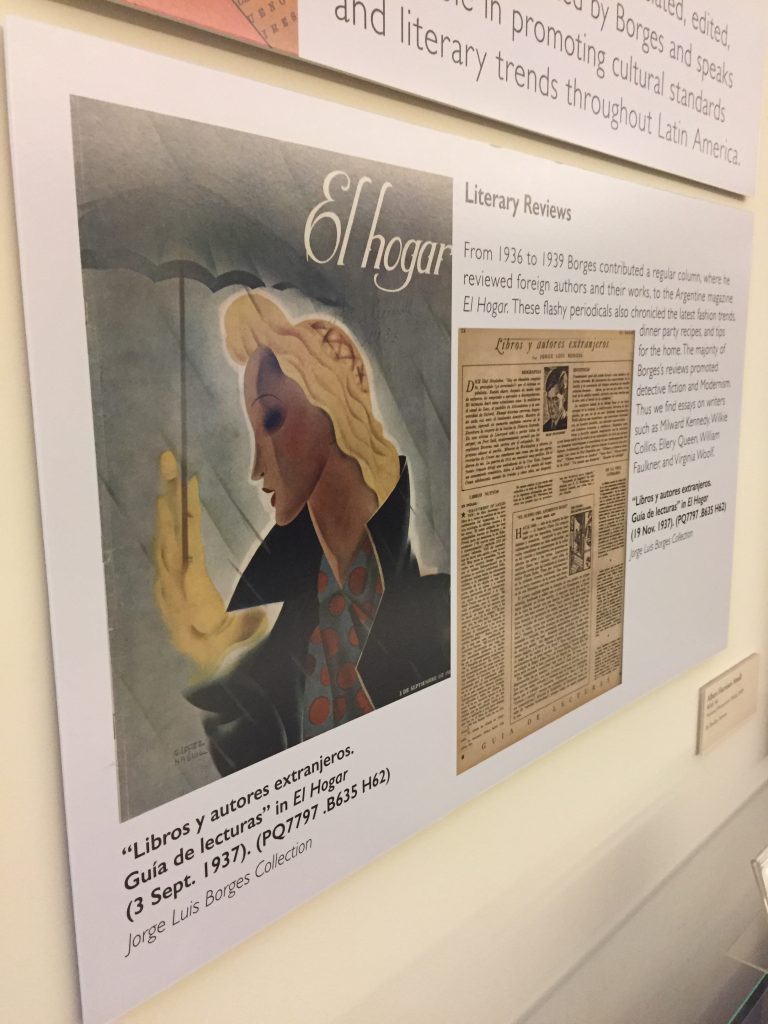

Borges empieza a introducir obras extranjeras al público argentino a través de sus reseñas literarias en el periódico “El Hogar.” (PQ7797 .B635 H62)

Borges empieza a introducir obras extranjeras al público argentino a través de sus reseñas literarias en el periódico El Hogar.

A pesar de que esta exhibición presenta un número limitado de materiales que hay dentro de la colección más grande, mi deseo es proveer un bosquejo provocativo de uno de los muchos caminos de investigación inexplorados dentro de su jardín de senderos que se bifurcan.

“Borges, Books, and Bibliography”

Nearly three-quarters of a century after the first appearance of his dizzying labyrinths and limitless libraries in Ficciones, Borges and (his) books continue to pique the interest of scholars and aficionados. Like most, I first encountered the University of Virginia’s Borges Collection by happy accident. Aside from the incredible experience of leafing through manuscripts and letters written by Borges himself, what struck me most about the collection was its extreme level of completeness. From a bibliographical standpoint, the holdings are ideal for any type of textual investigation. In addition to the rich manuscripts and rare periodicals, there is also at least one copy of each and every edition that Borges ever published throughout his lifetime (in some cases there are multiple copies of works almost as rare as the manuscripts!). In a sense, it is the perfect place to study the evolution of his writing process from manuscript to first edition to subsequent editions.

Having spent the better part of five years “under grounds” with the collection’s holdings, I’m always eager to talk about the unique treasures that one might find here, which, more often than not, leads others to ask, time and time again, how these items ended up at UVA. I, too, wondered this when I first laid eyes on original manuscripts from Fervor de Buenos Aires, pristine copies of the rare Prisma mural magazine, and incredible drawings in Borges’s distinctive hand. That said, I soon discovered that the presence of this collection at UVA makes perfect sense for a number of reasons. First is its link to the university’s largest collection strength, American history and literature, which should not be restricted to North America, but must logically extend to all of the Americas. Alongside this clear connection, I also see the university’s rich history of bibliography and the study of the book as object as crucial to understanding the decision to make UVA the home for these materials since they easily allow scholars to trace and identify any changes in a work (whether it be in wording or in the physical presentation of the text).

“Las Kenningar” was first published in a literary magazine before Borges had it printed separately by Francisco A. Colombo, a fine press printer. (PQ7797 .B635 H62)

My exhibition, “‘Armar páginas, corregir pruebas’: Jorge Luis Borges as Author, Editor, and Promulgator,” draws heavily on my dissertation research surrounding Borges and his various roles within the Argentine publishing industry, and it also speaks to the lesser-known strengths of the UVA collection and the potentials for future investigations. In addition to crafting superb prose and poetry, Borges was interested in the technical production of books, magazines, and literary journals. From early in his career he was deeply involved with correcting proofs and even setting type.

For me the hardest challenge of curating this exhibit was selecting a limited number of items and creating a logical narrative that would speak to Borges experts as well as students that have never heard of him. I eventually landed on three linked categories that would seamlessly illustrate his graceful navigation of private and public forms of writing: Author, Editor, Promulgator. More specifically, each of these three cases explores a different role that Borges held in the Argentine publishing industry during the 1930s and 1940s, in an effort to emphasize his impact on literary canons and educational standards.

“Author” presents a sampling of Borges’s collections of fiction and non-fiction such as Ficciones, El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan and Historia universal de la infamia.

“Editor” explores Borges’s deep-seated engagement with the physical form of the book with samplings from his two unique (fictitious) publishing houses, the Editorial Destiempo and the Editorial Oportet & Haereses.

“Un modelo para la muerte” a perplexing parody of the genre of detective fiction, was published under Borges’s and Bioy Casares’s joint pseudonym, B. Suárez Lynch, by their fictitious publishing firm, the Editorial Oportet & Haerese. (PQ .B635 M56 1946)

I’ve also included two original manuscripts that speak to his connections to other publishing houses and his writing of prologues for other authors’ works.

“Promulgator” highlights Borges’s behind-the-scenes editorial work in translating, editing, and prefacing works for various Argentine publishing firms.

Borges slowly began to introduce foreign works to Argentine readers through initial reviews in the magazine “El Hogar.” (PQ7797 .B635 H62)

While this exhibit features just a small number of items from the larger Borges collection, my hope is that it provides a thought-provoking snapshot of one of the many avenues of unexplored investigation into this writer’s garden of forking paths.