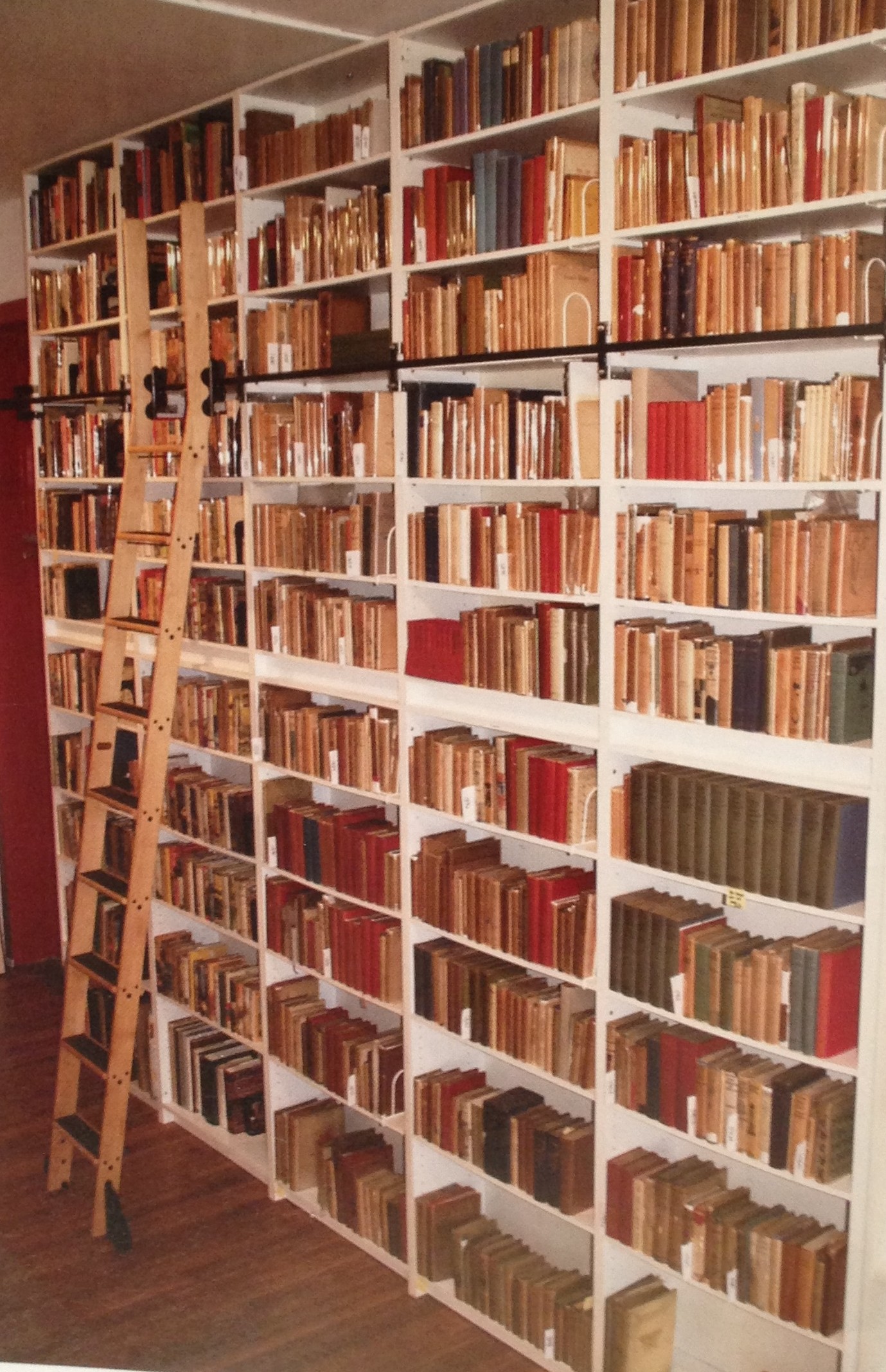

The Congalton collection of 19th-century books in original dust jackets and/or removable coverings as it looked before shipment to Charlottesville.

Yes, you read that correctly: the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library has implemented a dress code. Um, for books, that is. Henceforth all future book acquisitions from, say, 1880 to the present are requested to arrive suitably attired in original dust jackets whenever possible. Readers may continue to come as they are (within reason).

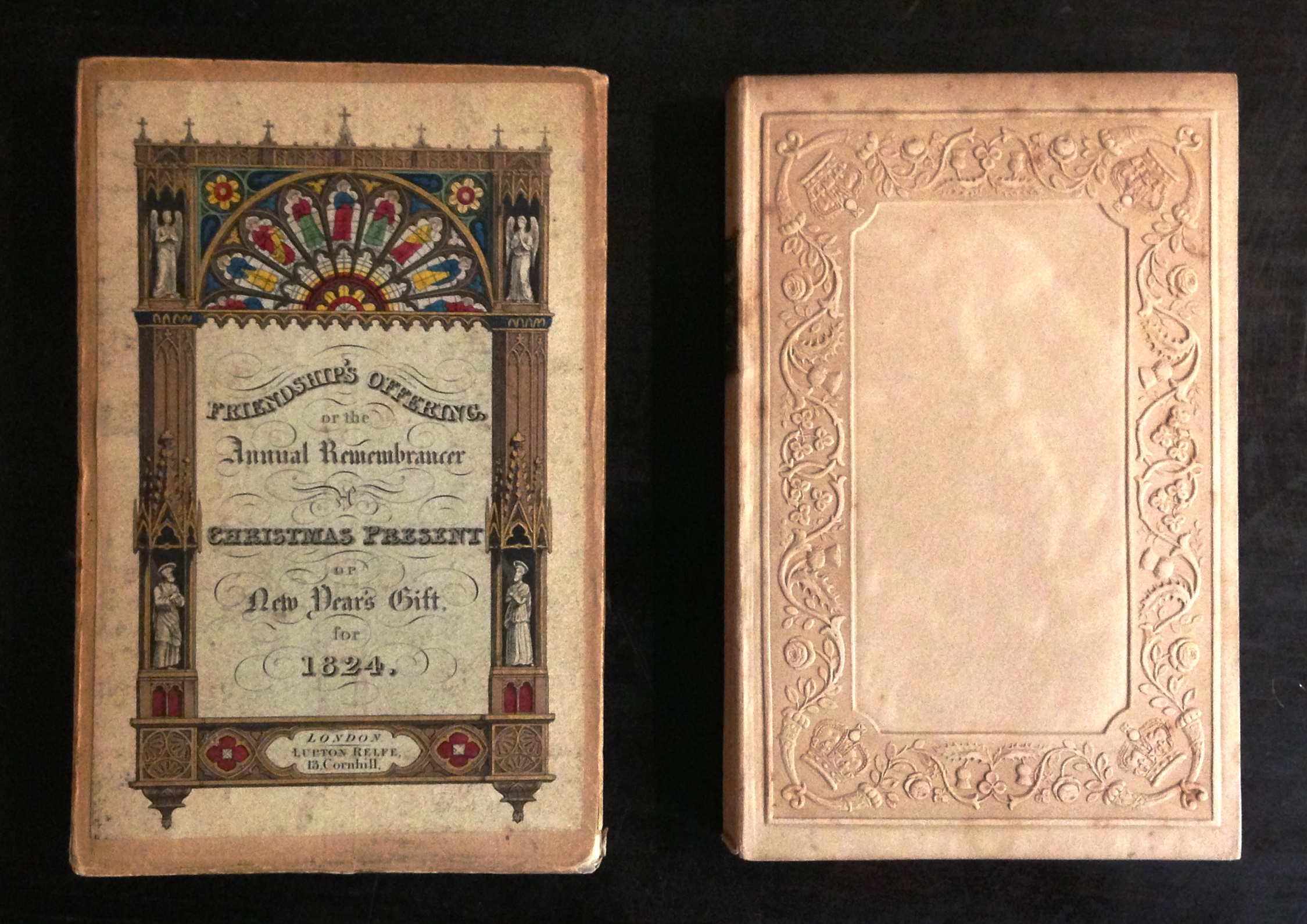

Friendship’s Offering, or the Annual Remembrancer, a Christmas Present or New Year’s Gift (London: Lupton Relfe, 1823) was one of the earliest English “gift books,” The fragile binding of embossed paper boards was given added protection (and a marketing boost) by a protective cardboard case, onto which was pasted a hand-colored engraved title.

Our new policy reflects one of three major acquisitions made this spring: a collection of 700 titles (in 829 volumes) of 19th-century American and English books (with a few European imprints) in original dust jackets and/or removable coverings. Formed over the past two decades by Tom Congalton, proprietor of Between the Covers Rare Books in Gloucester City, NJ, the collection is quite simply the largest such holding ever documented. Add to this the Small Special Collections Library’s existing holdings of nearly 200 19th-century titles, and the combined collection is—by far—the largest known in public or private hands.

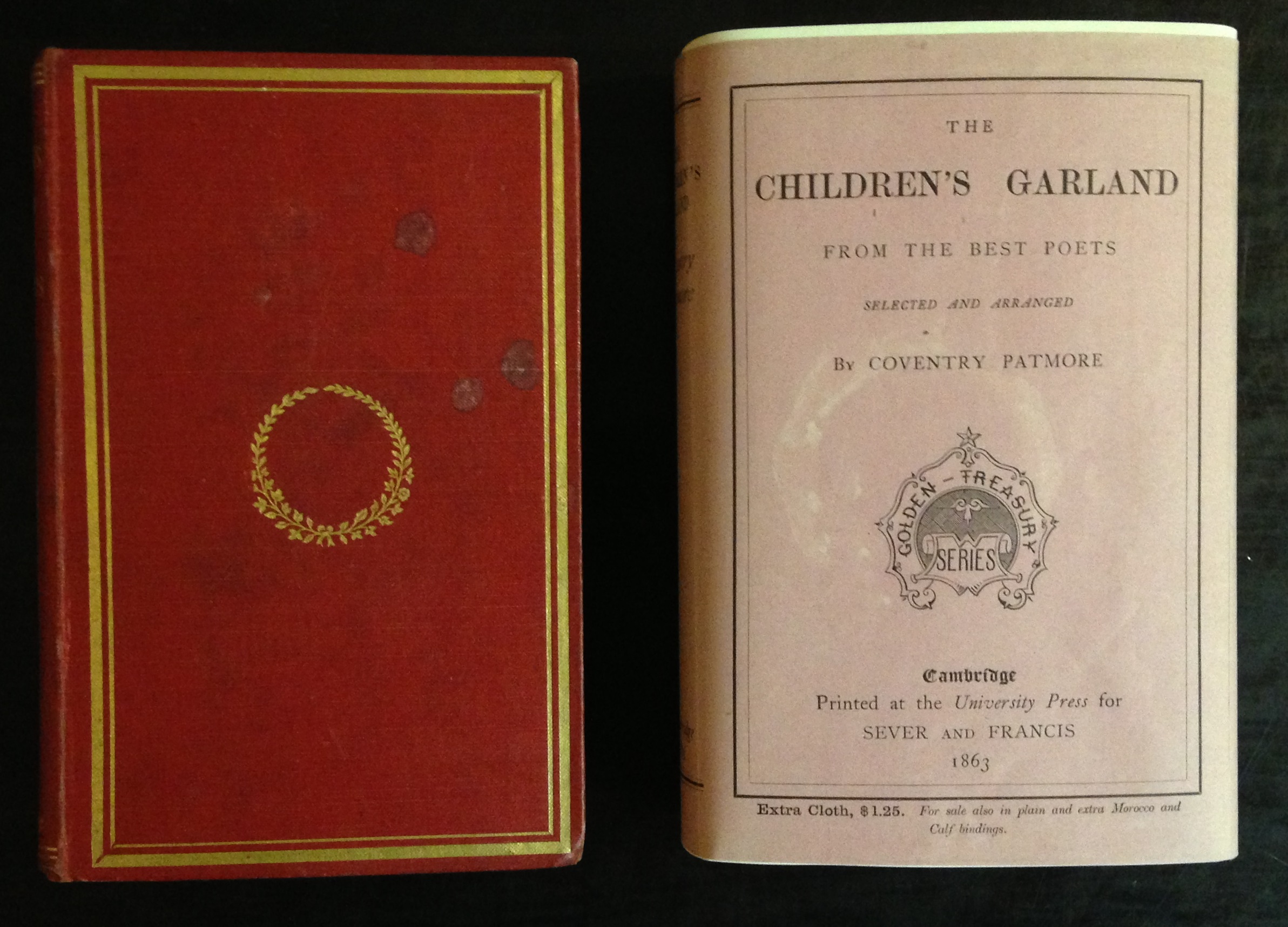

A fine example of one of the earliest surviving American dust jackets. The Children’s Garland from the Best Poets (Cambridge, Mass.: Sever and Francis, 1863) was issued in several binding styles, as advertised on the front of the dust jacket; this copy is bound in “extra cloth” and was priced at $1.25. The fragile jacket is printed on the spine and front panel only, and it is in the form of a wrap-around band sealed on the reverse. This example was torn open rather than slipped off the book, but otherwise it has been carefully preserved.

Given the ubiquity of dust jackets on 20th– and 21st-century books, how, you might well ask, could a collection of only a thousand volumes rank as the world’s largest for the 19th century? The answer lies in the changing views of collectors and libraries toward the preservation of these ephemeral coverings. The origins of the dust jacket remain murky—indeed, our new acquisition may now enable scholars to write an authoritative account of its early history—but we can trace dust jackets back to the introduction of publishers’ cloth and printed paper bindings during the 1820s. It was not until a century later, however, that some collectors and libraries began to reconsider their longstanding practice of routinely discarding dust jackets. Today few collectors and special collections libraries would consider throwing away dust jackets—especially early ones—but the damage has been done. Relatively few 19th-century jackets survive in institutional collections, and fewer still are available on the market. Acquiring and preserving these for research purposes will be slow and painstaking work.

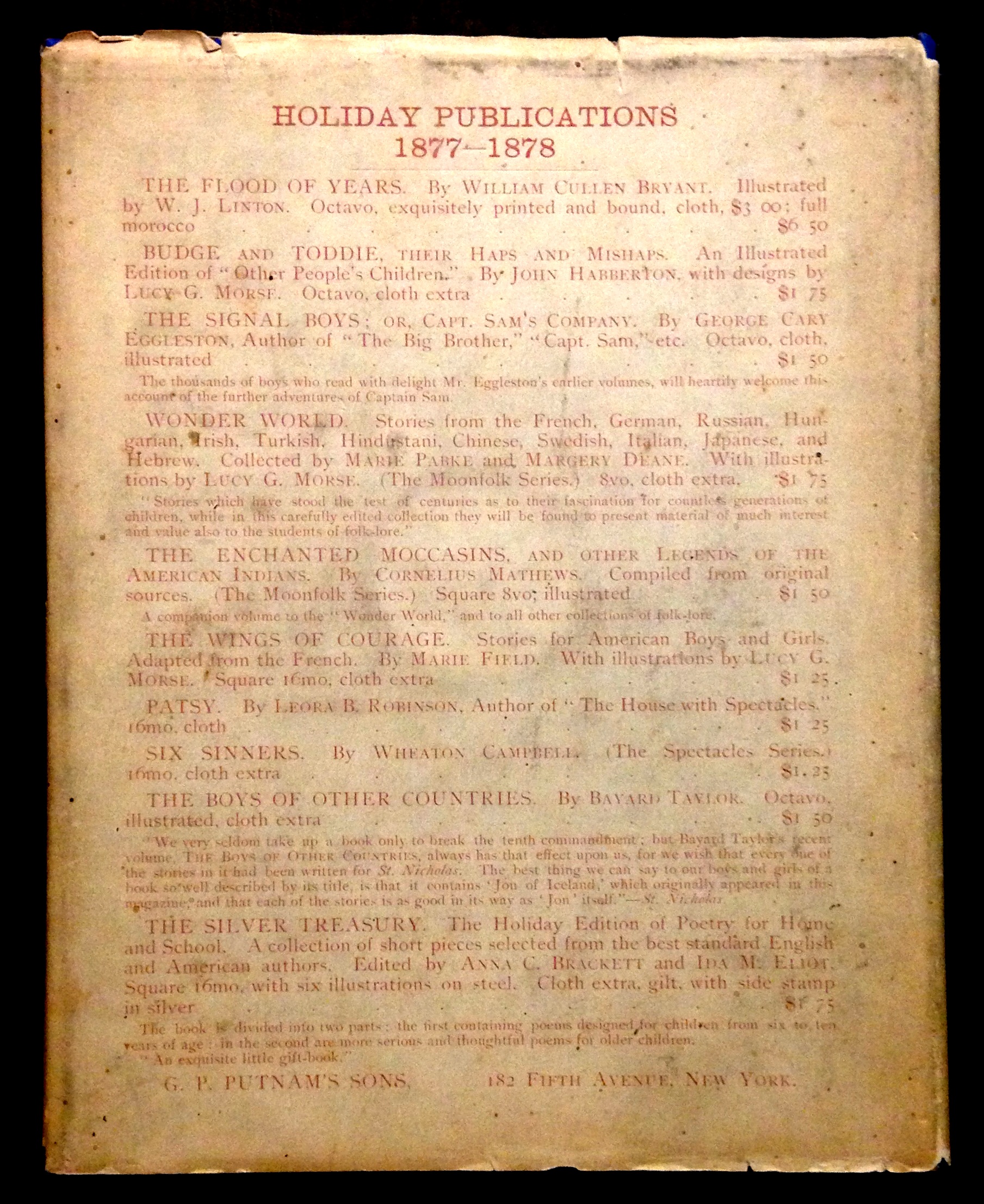

The back panel of this dust jacket, on a presentation copy of William Cullen Bryant’s The Flood of Years (New York: G.P. Putnam’s sons, 1878) is devoted to ads for this and other Putnam titles, with a new marketing innovation: smaller-print “blurbs” have been added for several books.

Dust jackets and removable coverings originally protected publishers’ bindings, especially those made of more expensive and fragile materials, from fading and excessive wear. When, in the mid-1820s, British and American publishers adopted the German practice of offering “gift books” and annuals bound in silk or fancy printed boards, they also provided decorative cardboard sheaths to protect the delicate bindings. Some publishers also sold books in sealed printed wrappings, which by definition had to be opened and discarded before the book could be read. These wrappings soon evolved into paper jackets with tucked-in flaps, but their adoption by publishers was slow and haphazard until the 1880s. Before then dust jackets tended to be plain or simply printed, carrying little more than author, title, and publisher on the spine and/or front cover.

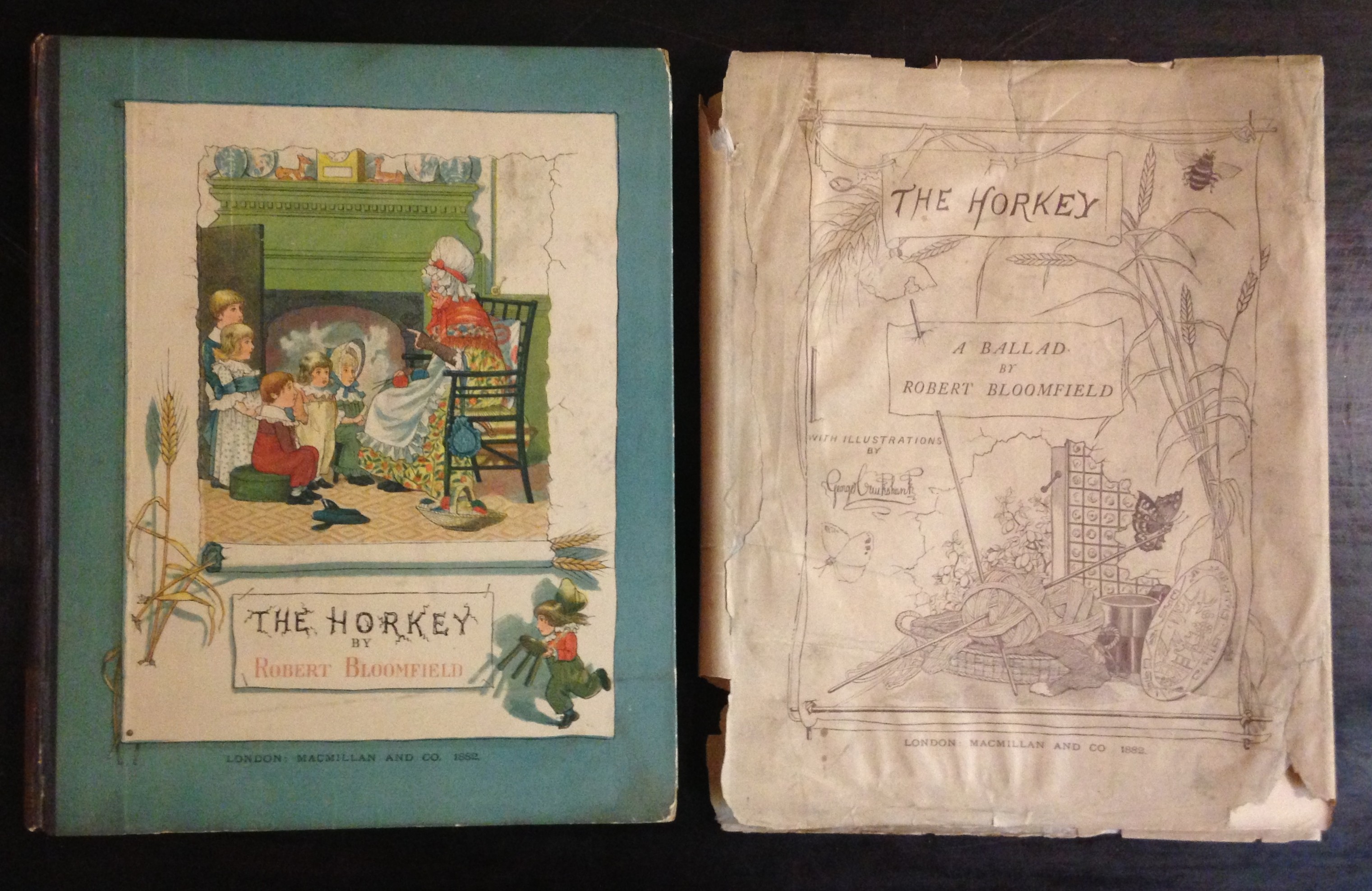

This color-printed children’s book–Robert Bloomfield’s The Horkey (London: Macmillan, 1882)–is bound in color-printed paper boards. The dust jacket replicates the color-printed title page design in a single color–perhaps color was considered an unnecessary extravagance for this ephemeral covering.

Dust jackets came into their own during the 1880s when many publishers adopted the practice. Most continued to be rather plain in design, serving a basic marketing function by identifying the author, title, and sometimes the price. Publishers often used the back panel to advertise their other recent publications, sometimes glossed with promotional “blurbs.” During the 1890s dust jackets were increasingly viewed by publishers as integral components of their marketing efforts. Many were pictorial in nature, often replicating a book’s decorative binding as closely as possible, though publishers freely experimented with dust jacket design. The previously plain jacket flaps were increasingly filled with publishers’ advertisements, blurbs, and other promotional text. Continuing a practice dating to the 1860s, publishers issued some titles for the holiday and gift markets in deluxe bindings protected by dust jackets and/or cardboard boxes. By the early 20th century, publishers began to favor plain edition bindings wrapped in highly decorative dust jackets.

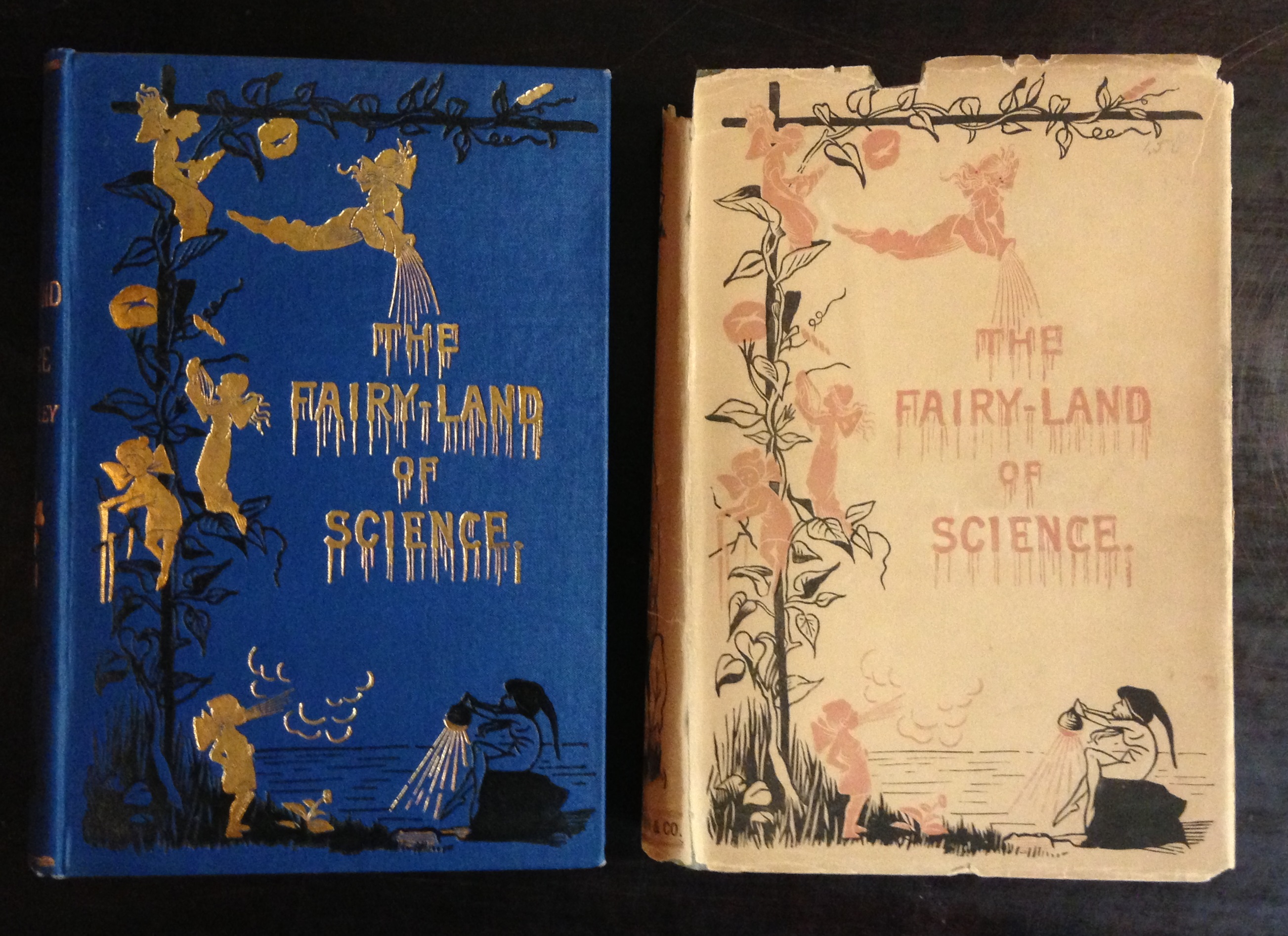

The dust jacket on Arabella Buckley’s The Fairy-Land of Science (New York: D. Appleton, 1881) is a very early example of a design which closely replicates in print the elaborate publisher’s cloth binding, here stamped in gilt and black ink.

Why collect dust jackets at all? The status of modern dust jackets as significant examples of graphic design worthy of serious study and collecting is now firmly established, as is our respect (some might say fetish) for the dust jacket covering a literary first edition. But in the words of G. Thomas Tanselle, dean of American bibliographers, president of the Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia, and author of Book-Jackets: Their History, Forms, and Use (Charlottesville, 2011): “less serious bibliographical attention has been paid to [dust jackets], it is probably safe to say, than to any other prominent feature of modern book production.” The Small Special Collections Library has long collected materials relating to the printing, publishing, distribution, and reception of texts, and it is only fitting that we strengthen our already formidable holdings with the primary sources necessary for studying this neglected aspect of the modern book.

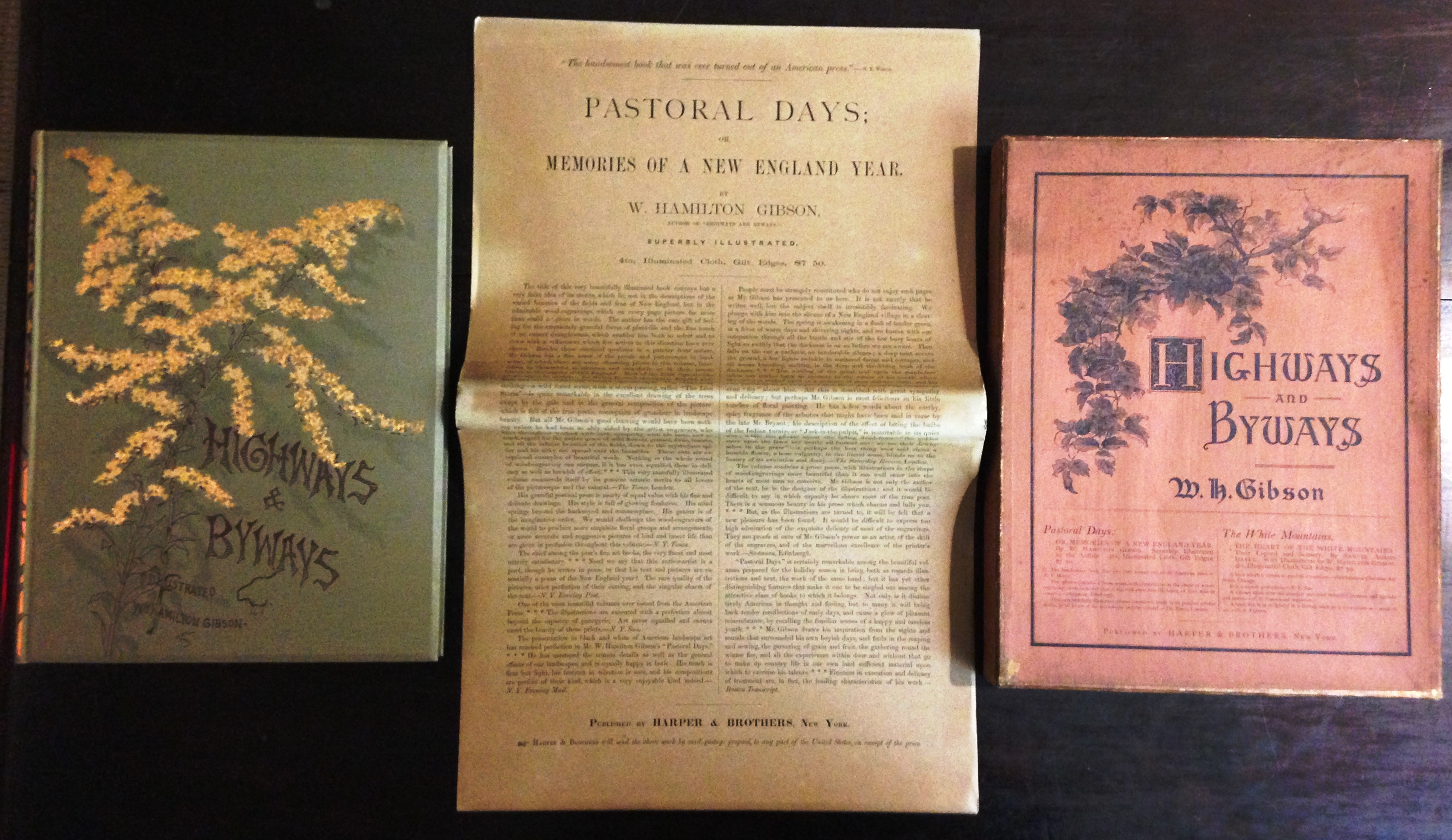

This expensive ($7.50) deluxe copy of W.H. Gibson’s Highways and Byways, or Saunterings in New England (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1883) received elaborate and unusual packaging. The publisher’s richly gilt binding is stamped on high-quality bookcloth. Protecting the binding is a dust jacket consisting of a large printed advertisement for another Gibson work published by Harper in similar format. The book is laid in the publisher’s protective cardboard box bearing advertisements for two Gibson works issued in matching format.