In recent months U.Va. has had unusual opportunities to enhance its already strong collections on 19th-century planographic printing. Prior to the invention of lithography by Alois Senefelder in 1796, printers used a variety of relief (letterpress, woodcut &c.) and intaglio (engraving, etching &c.) processes for replicating text and image. Senefelder’s innovative method of printing from a flat surface offered printers a new tool which, thanks to continuing refinement during the 19th century, emerged as the leading method for printing multicolor illustrations. And by the later 20th century, offset lithography would supplant letterpress as the preferred method for printing text.

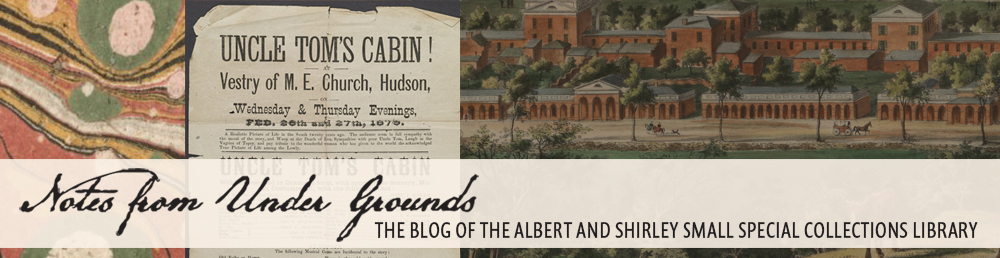

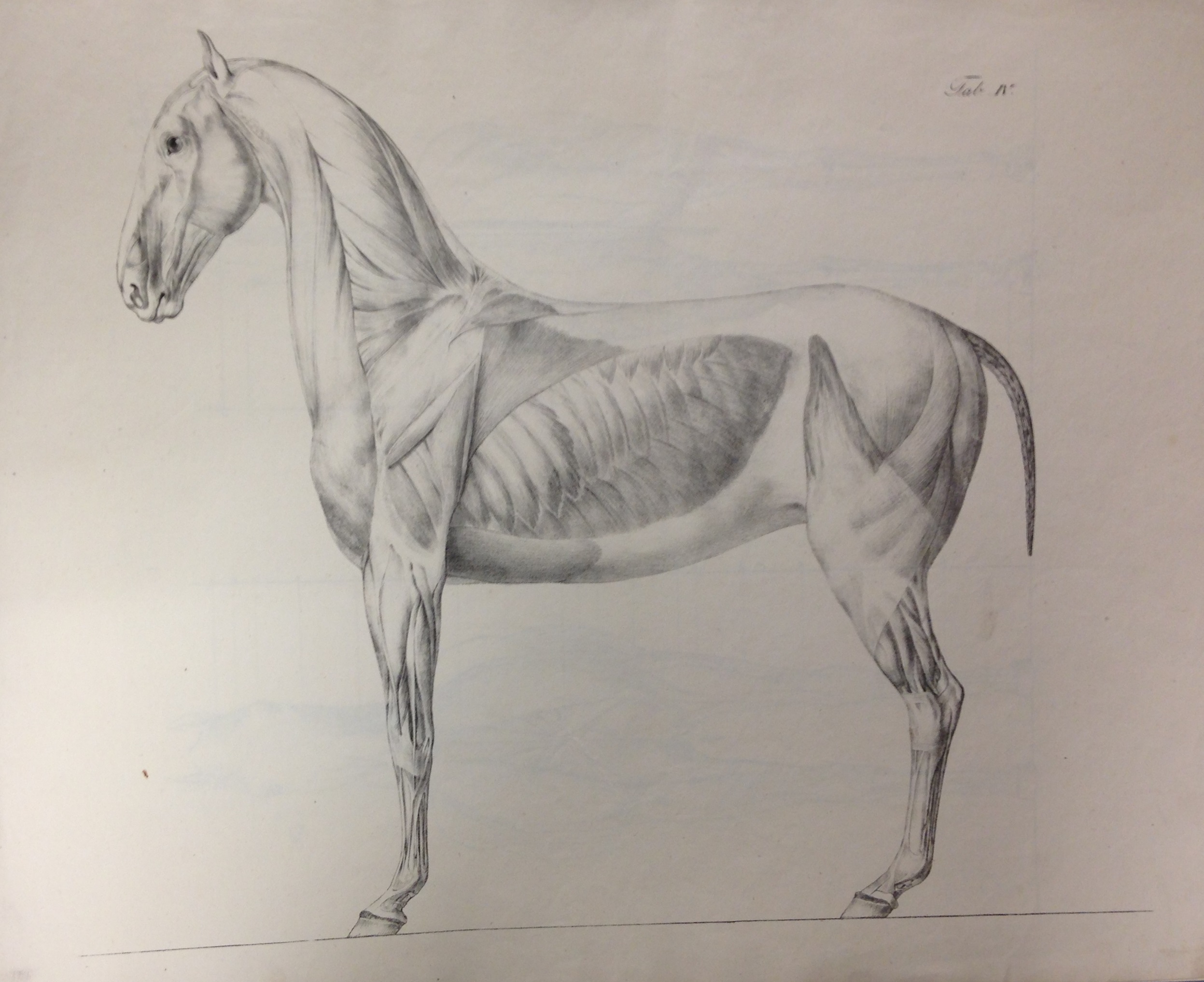

A lithographed plate from Konrad Ludwig Schwab. Anatomische Abbildungen des Pferdekörpers (Munich, 1820 ) (SF765 .S45 1820)

Because the technologies of lithography inform many aspects of 19th-century printing, the graphic arts, and book culture, the Small Special Collections Library has long sought to acquire a representative collection of technical manuals and printing specimens documenting lithography’s gradual ascendancy. Included are rare lithographic “incunabula” printed up to ca. 1820. Five years ago we were fortunate to acquire a fine copy of Konrad Ludwig Schwab’s Anatomische Abbildungen des Pferdekörpers (1813) published (as were many of the earliest lithographed books) in Munich, and illustrated with several large plates depicting horse anatomy. To it we have now added the equally rare second edition (Munich, 1820). This is no mere reprint, for the plates have been redone in more accomplished fashion, demonstrating how far lithography had progressed in only a few short years.

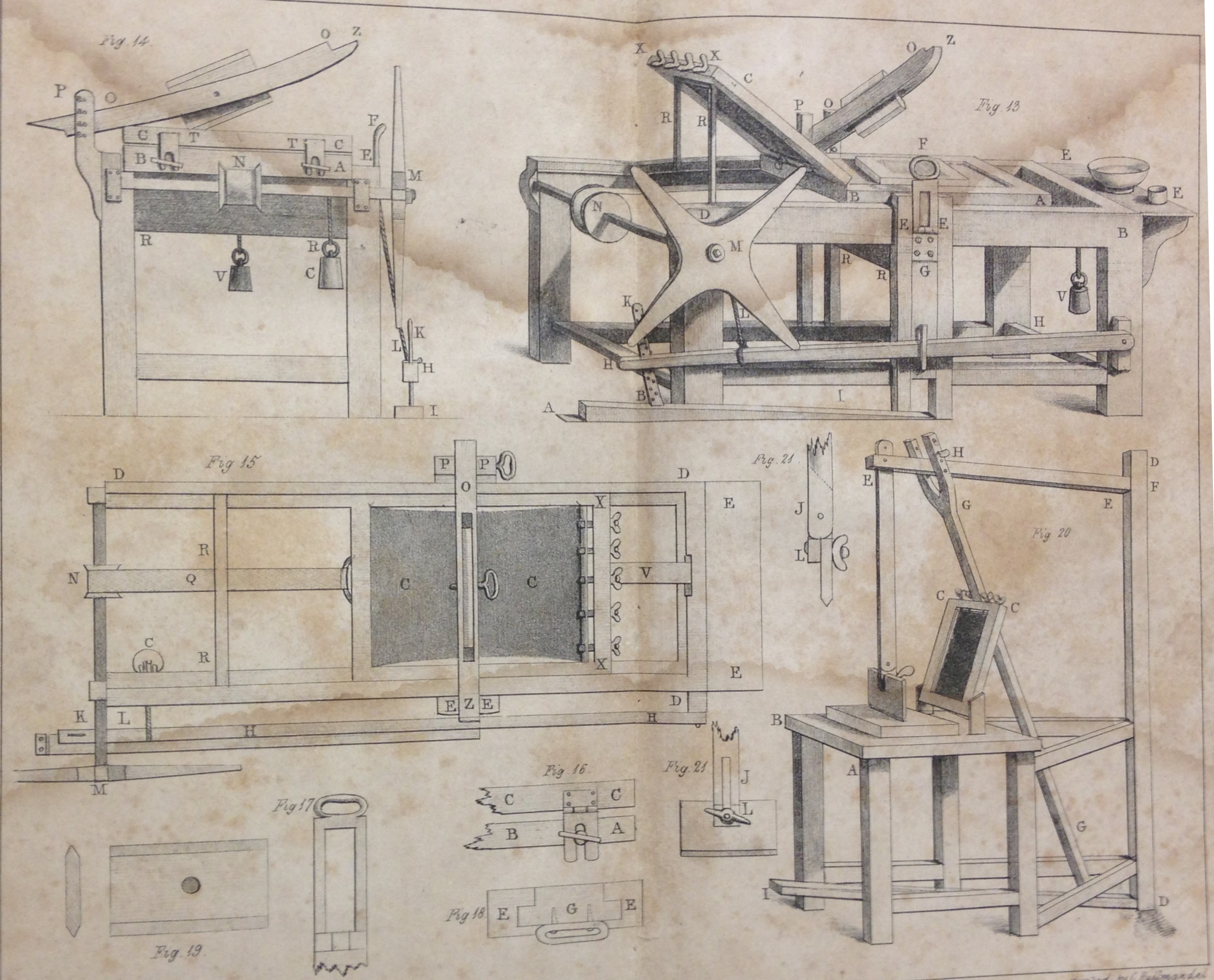

An early lithographic press and related equipment as depicted in Antoine Raucourt de Charleville, A manual of lithography, or memoir on the lithographical experiments made in Paris (2nd ed., London, 1821) (NE2420 .R25 1821)

Lithography quickly spread throughout Europe and beyond, particularly after 1818 when Senefelder published the first comprehensive manual. Others followed in quick succession, and through these we can trace the many technical innovations introduced during the 1820s and 1830s. By 1819 English printers could read not only Senefelder’s work, but also the leading French manual (by Antoine Raucourt de Charleville) in an English translation prepared by the London lithographer Charles Hullmandell. We recently acquired the second edition (1821), to which Hullmandell appended plates depicting a lithographic press, which looked and operated far differently from relief and intaglio presses. Another recent acquisition is the very rare Mémoire sur l’art du lithographe (Paris, [1829]) of Alphonse Chevallier. Included is a set of progressive plates illustrating Chevallier’s methods for creating certain artistic effects lithographically.

![Two stages in the creation of a lithographic image, from Alphonse Chevallier, Mémoire sur l’art du lithographe (Paris, [1829]) (NE2420 .C54 1829)](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/B5.jpg)

Two stages in the creation of a lithographic image, from Alphonse Chevallier, Mémoire sur l’art du lithographe (Paris, [1829]) (NE2420 .C54 1829)

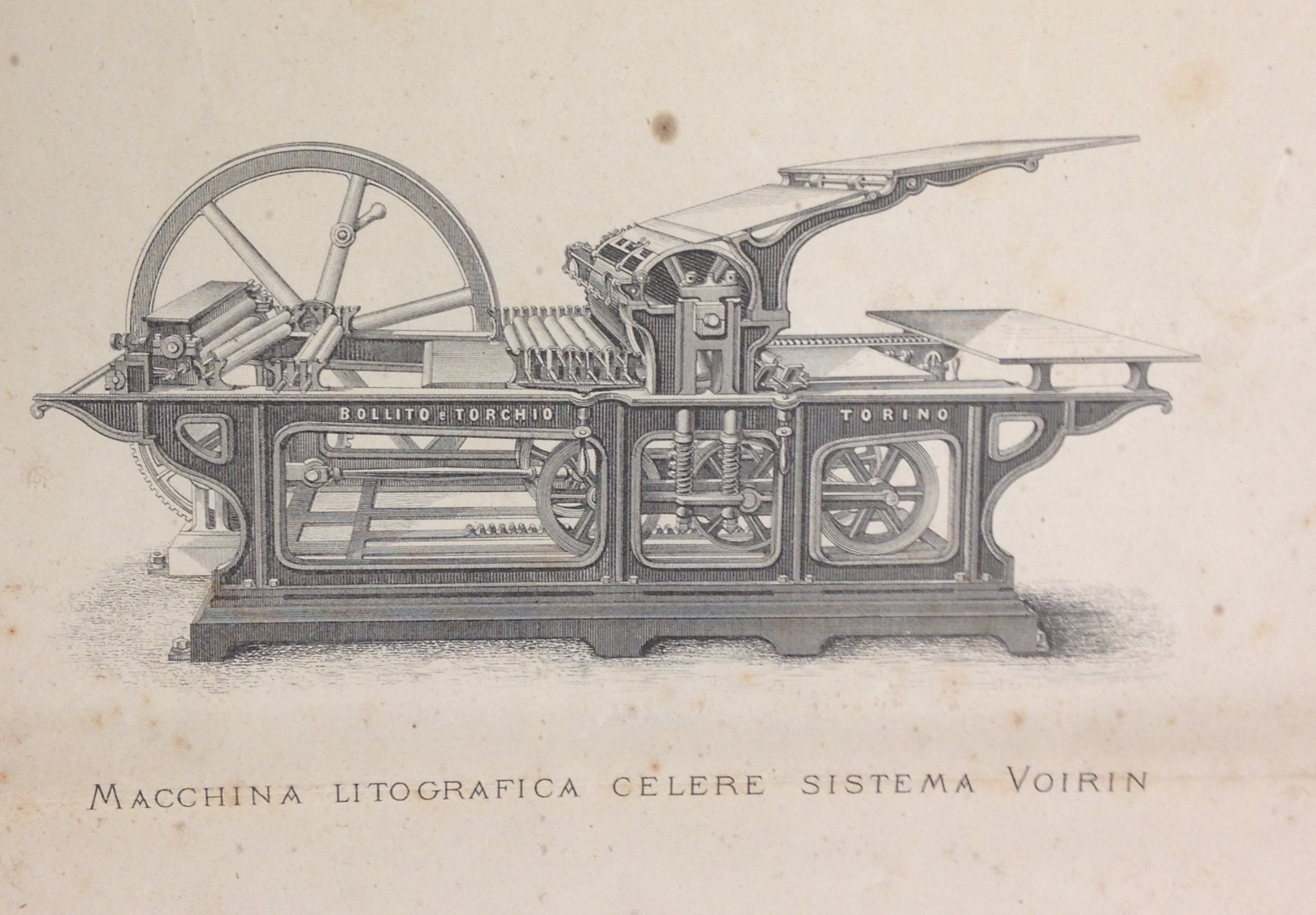

A steam-powered lithographic press illustrated in Camillo, Doyen, Trattato di litografia: storico, teorico, pratico ed economico (Turin, 1877) (NE2425 .D68 1877)

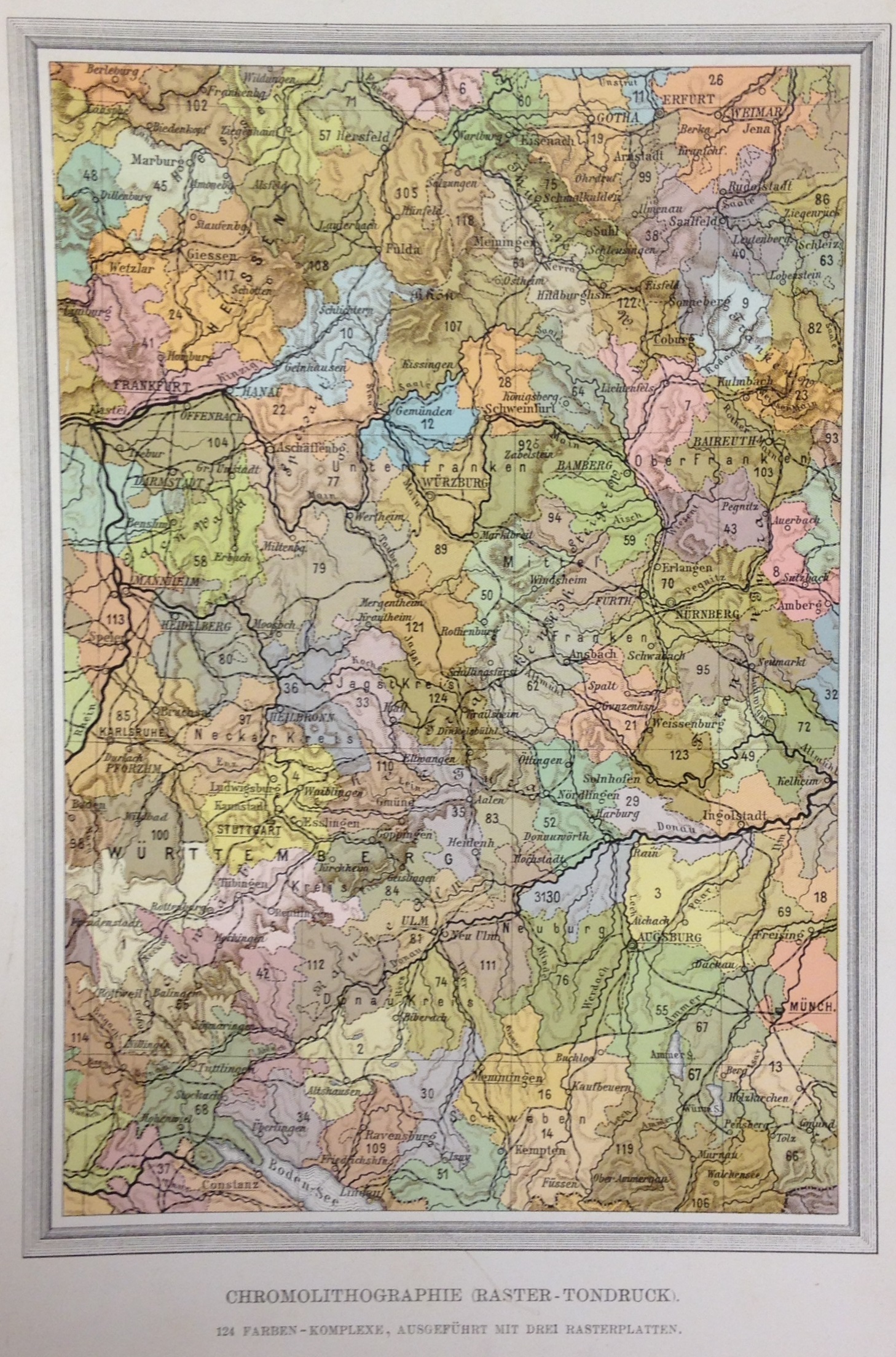

By 1900 German and Austrian lithographers were perhaps the most accomplished in Europe, producing high quality book illustrations and other work for publishers as far afield as the United States. The text and sample plates to Friedrich Hesse’s Die Chromolithographie (2nd ed., Halle, 1906) are important for understanding and identifying the many variant processes in the commercial lithographer’s toolkit.

A specimen chromolithographed map inserted as a plate in Friedrich Hesse, Die Chromolithographie (Halle, 1906) (NE2500 .H47 1906)

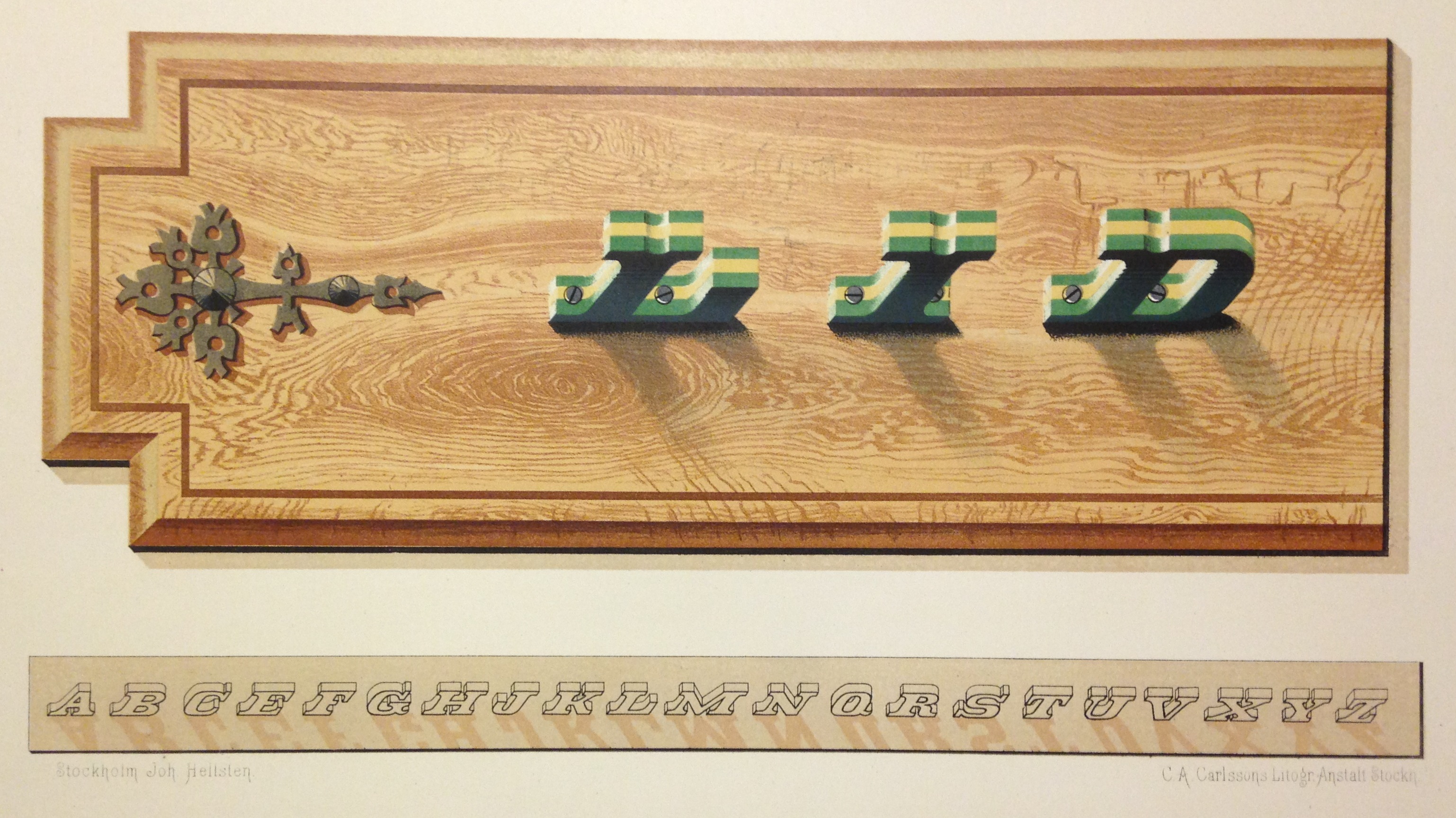

Printers have long sought to demonstrate and advertise their prowess through specimen work, and lithographers have been no exception. Perhaps the finest early chromolithographic printing was that executed by the Strasbourg firm of Frédéric Émile Simon. During the 1830s Simon teamed with the innovative calligrapher Jean Midolle to issue three extraordinary specimen books, one of which we have now acquired: Album du Moyen Âge (1836). That many of its plates are heightened with dusted gold, silver, and bronze powders, and even some discreet hand coloring, does not detract from their beauty and technical mastery. Fifty years later the Swedish sign painter advertised his work to potential clients by issuing Skyltmotiv (1884), a very rare portfolio containing 30 sample designs of his best work. Here the ability of Stockholm chromolithographer C. A. Carlsson to reproduce woodgraining and three-dimensional effects planographically is nothing short of miraculous.

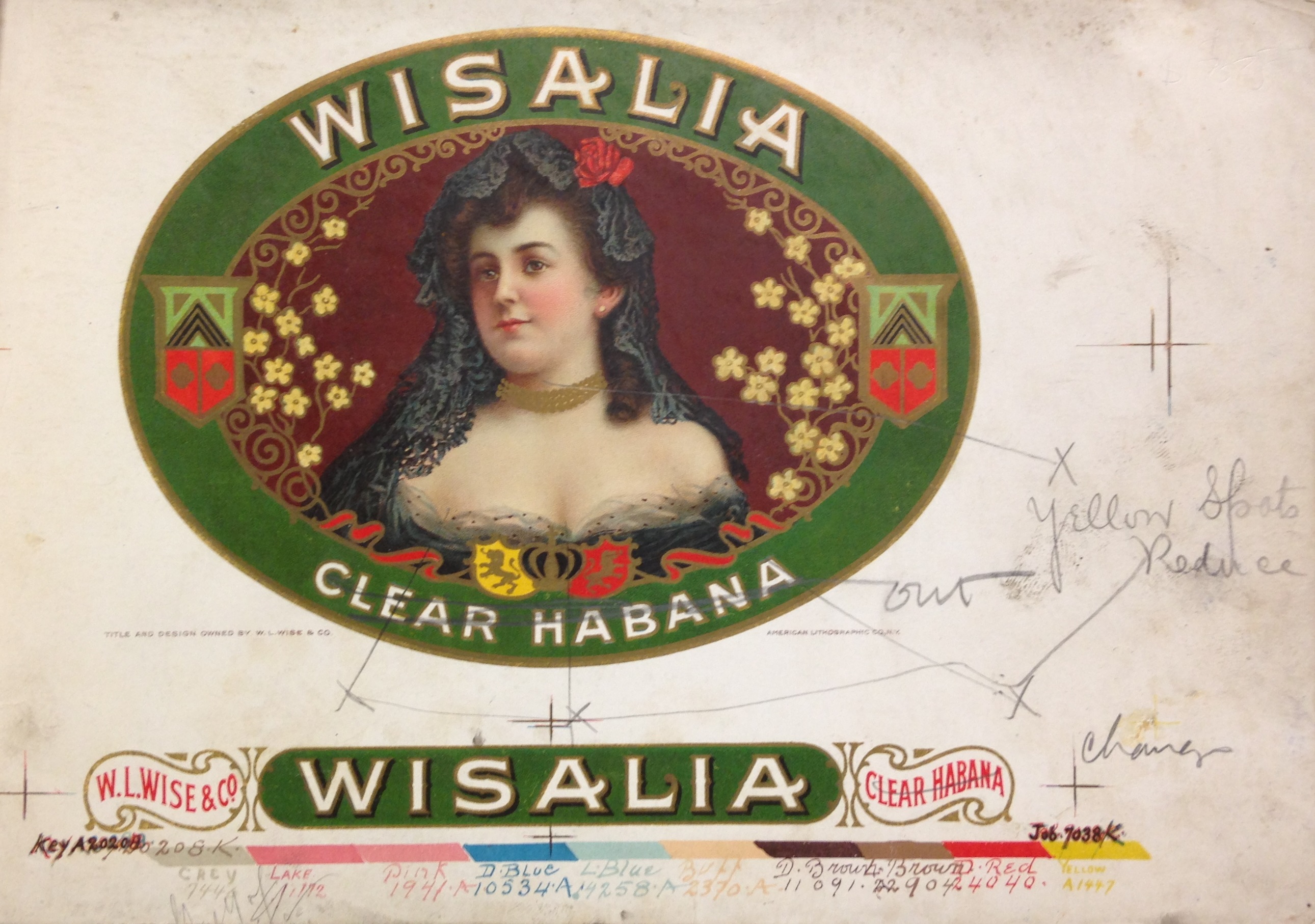

By 1900 it was not unusual for lithographers to print chromolithographic images in 20 or more colors, each applied with a different lithographic stone. A successful image required not only perfect registration, but the careful application of colors in proper sequence to achieve the desired effect. How this was done is illustrated through a set of progressive proofs we recently acquired. Formerly in the archive of the American Lithographic Co., it comprises the firm’s official set of 39 proofs documenting job no. 7038K: a cigar box label printed ca. 1900. Many proofs bear annotations indicating corrections to be made, followed by the corrected proofs. At front is the completed image (still marked for correction) showing at bottom a color bar with the ten hues employed, applied in sequence from right to left.