Today, the folks over at UVA’s facebook page invited curator Molly Schwartzburg to share with them some of her favorite items in the miniature book collection on the Facebook Live streaming video platform. For those of you not on Facebook, here’s the video. We’re impressed that those teeny tiny books are actually in pretty good focus! Check out some of our beautiful and unusual minature treasures.

Category Archives: General

John O’Brien’s Literature Incorporated Wins the Louis Gottschalk Prize

It is one thing to write a book. It is quite another for that book to receive widespread acclaim from one’s peers, as is the case with Literature Incorporated: The Cultural Unconscious of the Business Corporation, 1650-1850, the most recent work by John O’Brien, NEH Daniels Distinguished Teaching Professor in U.Va.’s Department of English. Literature Incorporated has been awarded the Louis Gottschalk Prize, presented annually “for an outstanding historical or critical study on the eighteenth century” by the American Society for Eighteenth Century Studies.

One need not be aware of the Supreme Court’s 2010 ruling in Citizens United or of Mitt Romney’s statement that “corporations are people” to benefit from a close reading of Literature Incorporated. Its subject is the corporation, “an abstraction that gathers up a long history of institutions and practices as varied as city governance, guild organization, state-sponsored colonial exploration, money lending, insurance, slave trading and university funding.” Its method is to trace the trope of incorporation in a wide range of Anglo-American texts, including “economic tracts, legal cases, poems, plays, essays, novels, and short stories.” And its goal “is to discover some of the ways in which language has ‘repeated’ the influence of the corporation to us, given it form in our imaginations.”

The U.Va. Library is proud to have earned a place in the book’s Acknowledgements. Indeed, most of the works discussed in Literature Incorporated (and many more that inform and amplify its arguments) can be found in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. Here is a modest selection, which we invite you to come explore in more depth.

King as corporation, comprised of the bodies of his subjects. Detail from the engraved title page to Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (London, 1651). (E 1651 .H658; Tracy W. McGregor Library of English Literature)

Literature Incorporated begins with Thomas Hobbes’ work of political theory, Leviathan (1651). Its famous engraved title page “offers an image of incorporation, of the people of a realm incorporated into the sovereign.” Although Hobbes viewed private corporations as potential rivals to government, O’Brien shows how Alexander Hamilton and John Marshall, among others, appropriated Hobbes’ language in support of corporations.

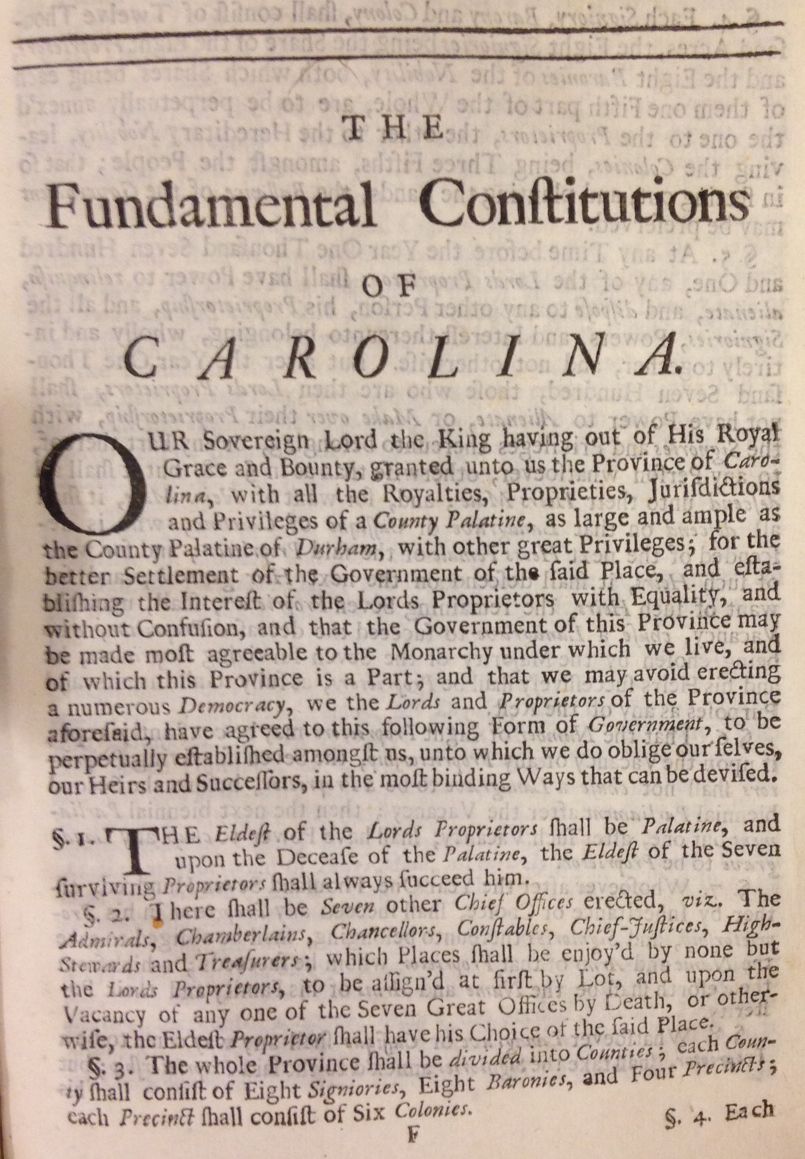

The Carolina Company’s vision for its American colony, drafted in large part by John Locke. The Two Charters Granted by King Charles IId to the Proprietors of Carolina (London, 1698). (A 1698 .G746; Tracy W. McGregor Library of American History)

Among the earliest English corporations were entities such as the Carolina Company, chartered by the sovereign to promote colonial settlement and trade. The philosopher John Locke was instrumental in developing the English mercantilist system, and O’Brien traces Locke’s crucial role in drafting the company’s Fundamental Constitutions (1669; final edition 1698), in which the Carolina proprietors envisioned the society they hoped to establish in the New World. Indeed, Locke’s empiricist philosophy permeates the document.

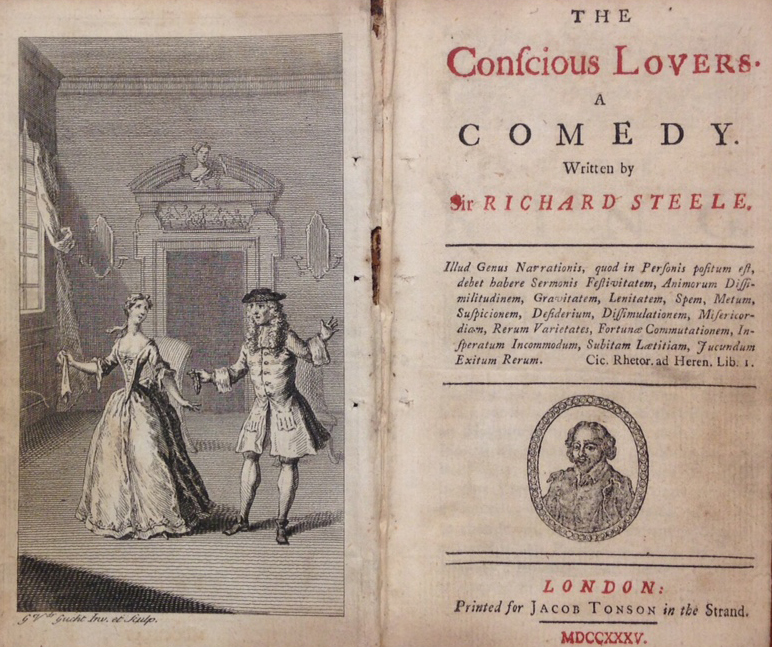

Frontispiece and title page to an early edition of Richard Steele’s The Conscious Lovers (London, 1735). (PR3704 .C66 1735)

Another such company, the South Sea Company, was at the heart of one of the greatest financial bubbles of all time, the South Sea Bubble of 1720. The speculative frenzy and resulting financial crash can be traced in many contemporary literary works, such as Sir Richard Steele’s play, The Conscious Lovers (1720). To the familiar plot lines of marriage and mistaken identity Steele added innovative complications concerning property rights. Steele also found himself accused publicly, through his involvement with the Drury Lane Company, of creating a theatrical equivalent of the South Sea Bubble to unfairly inflate the play’s ticket prices.

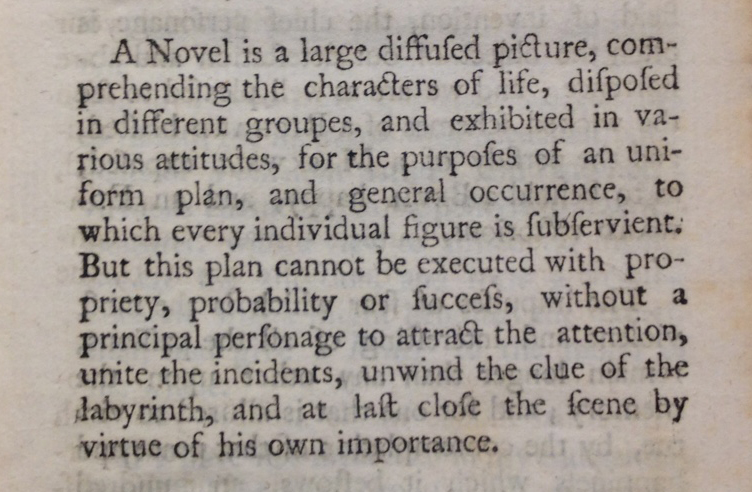

Tobias Smollett on why a novel needs a “principal personage,” from The Adventures of Ferdinand Count Fathom (London, 1753). (PR33694 .F54 1753 v.1)

The 18th century also saw the rise of insurance companies, which offered protection from risk and the fickle winds of divine providence. O’Brien demonstrates how contemporary English fiction’s “well-known investigations of risk and reward look different when they are read in the context of insurance history.” A perfect example is Tobias Smollett’s Adventures of Peregrine Pickle (1751), in which the plot is driven by Peregrine’s involvement with two different insurance policies. O’Brien also invokes Smollett’s famous statement, in the preface to The Adventures of Ferdinand Count Fathom (1753), that a novel requires “a principal personage to attract the attention, unite the incidents, unwind the clue of the labyrinth, and at last close the scene by virtue of his own importance.” In O’Brien’s words, the protagonist of a novel “resembles the corporation itself, a prosthetic person who helps bring the broader organization of a specific kind of economic activity into representation.”

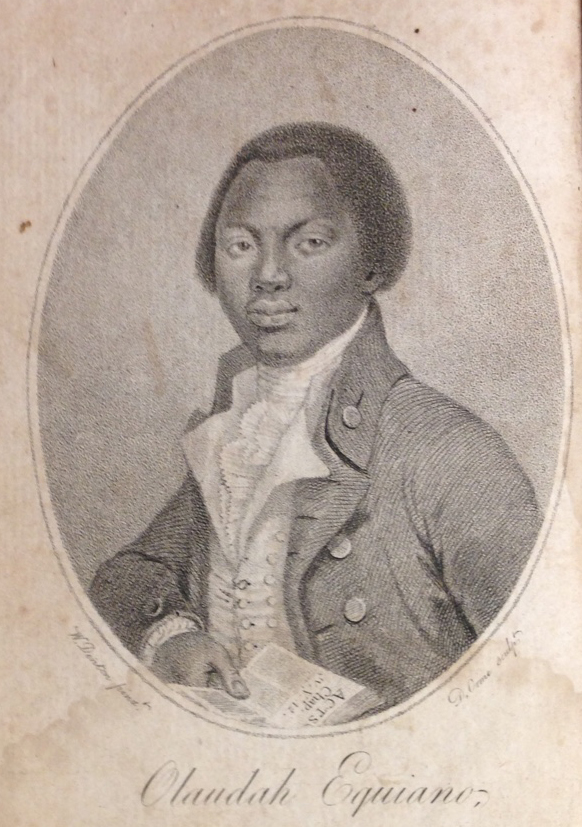

Frontispiece to The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano (London, 1789). (CT2750 .E7 1789; Gift of Mrs. Emily D. Kornfeld)

During the late 18th century, the London Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade waged a successful abolitionist campaign. O’Brien traces how “the society became a corporate voice that found itself emulating the very entities that it sought to attack,” for example, through its frequent use of an emblem featuring a supplicatory slave on bended knee. However, one key abolitionist publication—The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano (1789)—deliberately separated itself in form and content from this corporate voice, instead establishing itself “as a kind of corporate representative [of] ‘the African.’”

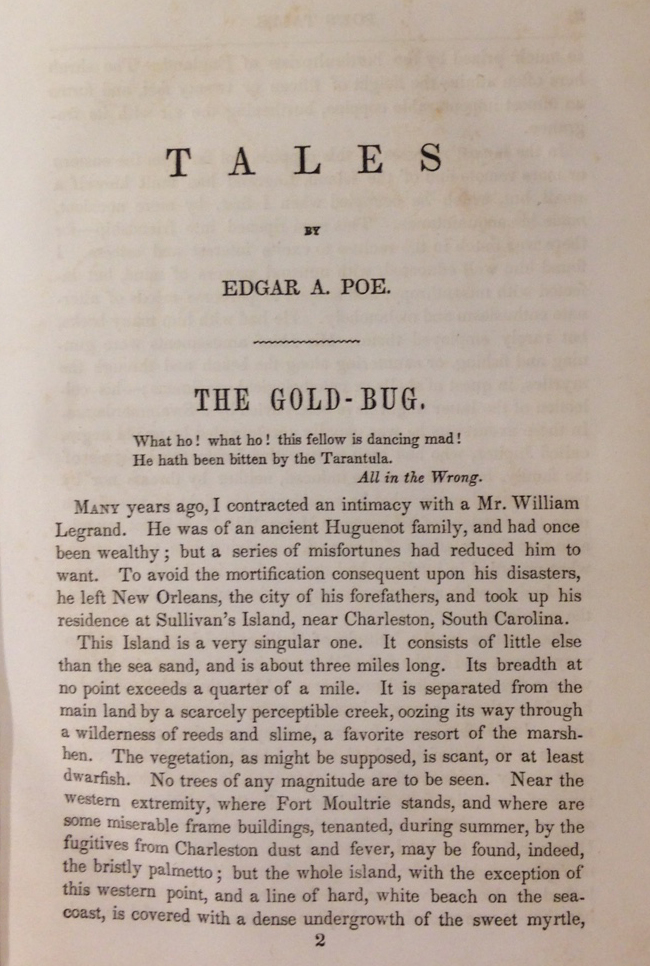

Beginning of Edgar Allan Poe’s story, The Gold-Bug, which leads off his Tales (New York, 1845). (PS2612 .A1 1845 copy 3; Gift of D. N. Davidson)

Literature Incorporated concludes with a discussion of Anglo-American literary responses to the fiscal and banking crises of the 1820s, 1830s, and 1840s. In particular, O’Brien offers a close reading of The Gold-Bug, the lead-off story in Edgar Allan Poe’s Tales (1845) and his most popular with contemporaries.

And to wrap up: hold the date! Another recent recipient of the Louis Gottschalk Prize—David Hancock, Professor of History at the University of Michigan—will deliver this year’s Thomas Jefferson Foundation Lecture on Wednesday, April 5, 2017 at 4:00 p.m. in the auditorium of the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. His talk, “The Man of Twists and Turns: Personality, Portrait & Power in the Re-Shaping of Empire,” concerns the 2nd Earl of Shelburne, the British prime minister who helped negotiate an end to the American Revolution. The lecture is co-sponsored by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation and the U.Va. Library.

…And to all a Good Night! —that means you, John Boy

The holidays are upon us! As we watch the students head home, the weather cool (well…not as much as we might like), and twinkling lights appear all over town, we are adding to the holiday mood with a special post from Reference Coordinator Regina “Ms. Claus” Rush. Enjoy, and be sure to check our website for holiday hours in the next couple of weeks. Thanks for the movie recommendation, Regina!

Inquire of any of my colleagues at Special Collections Library and they will attest that I govern my life by the Golden Rule. No, not that Golden Rule. I follow the Golden Rule according to Ebenezer Scrooge. Allow me to clarify further: not the Bah-Humbug Scrooge, but the kinder-gentler-post-three-ghostly-visitations Scrooge. His Golden Rule reads, “I will honour Christmas in my heart and try to keep it all year!”

Throughout the year, my colleagues can count on me to daily mention a Christmas movie, sing a verse or two from a favorite Christmas carol, or contemplate my plans for the coming year’s Christmas tree themes for my home. These are ways that I keep the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Future at bay. So when asked by my colleague Molly Schwartzburg to write a post highlighting an item from our collection pertaining to Christmas, quicker than “Jack Frost can nibble at your nose,” I. WAS. ON. IT!

Regina, at right, with fellow snow fan and Reference Coordinator Anne Causey. They both wish that the claim made on this Reading Room holiday decoration was TRUE!

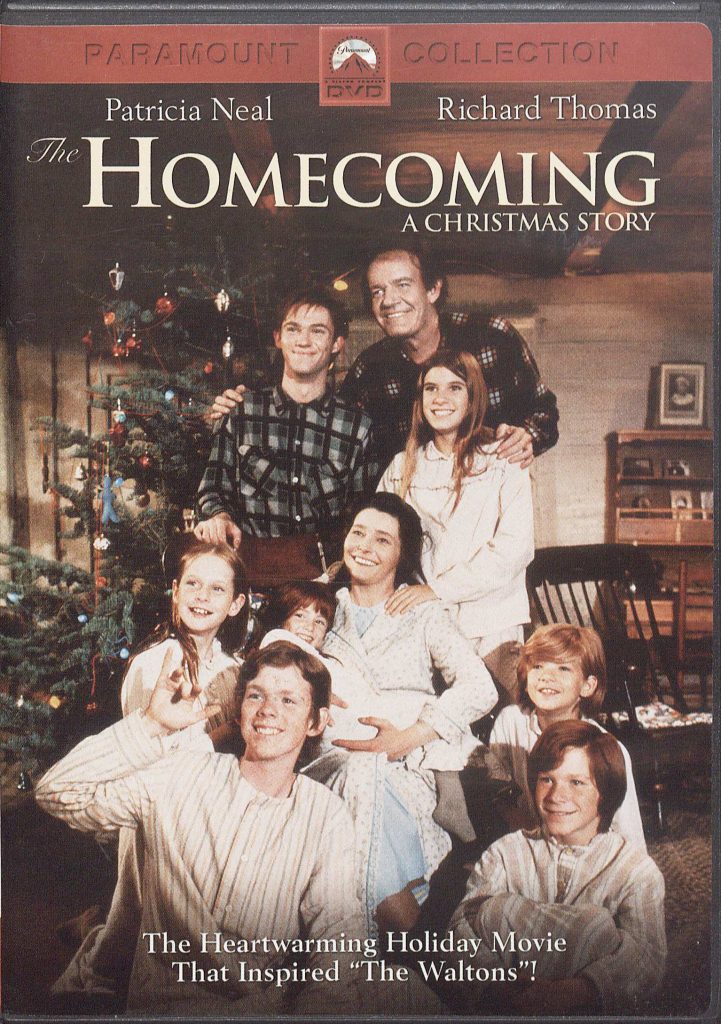

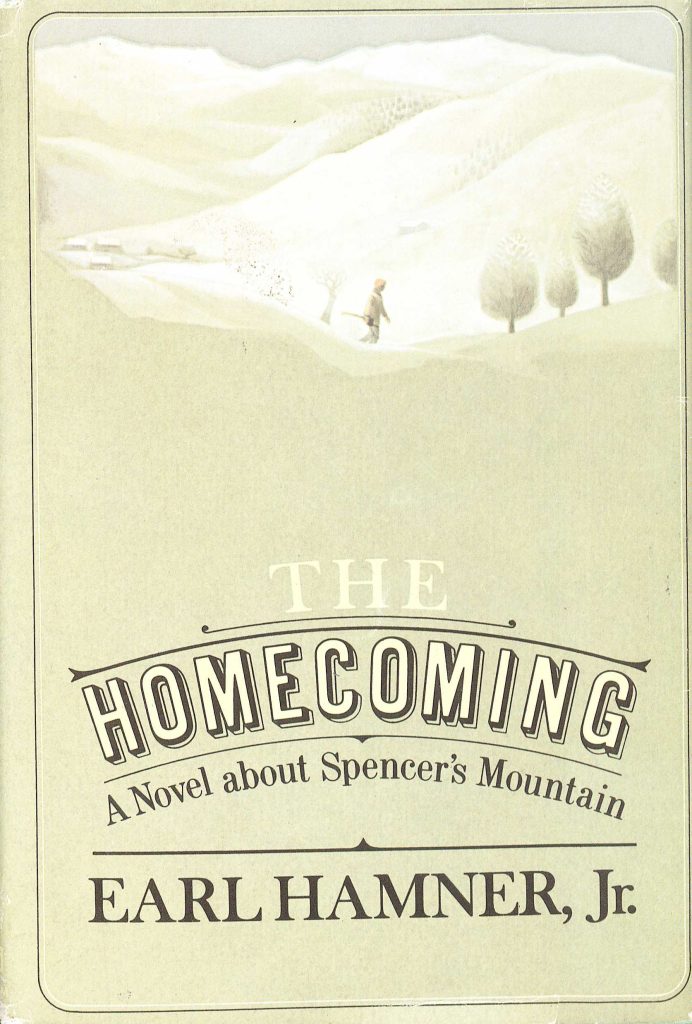

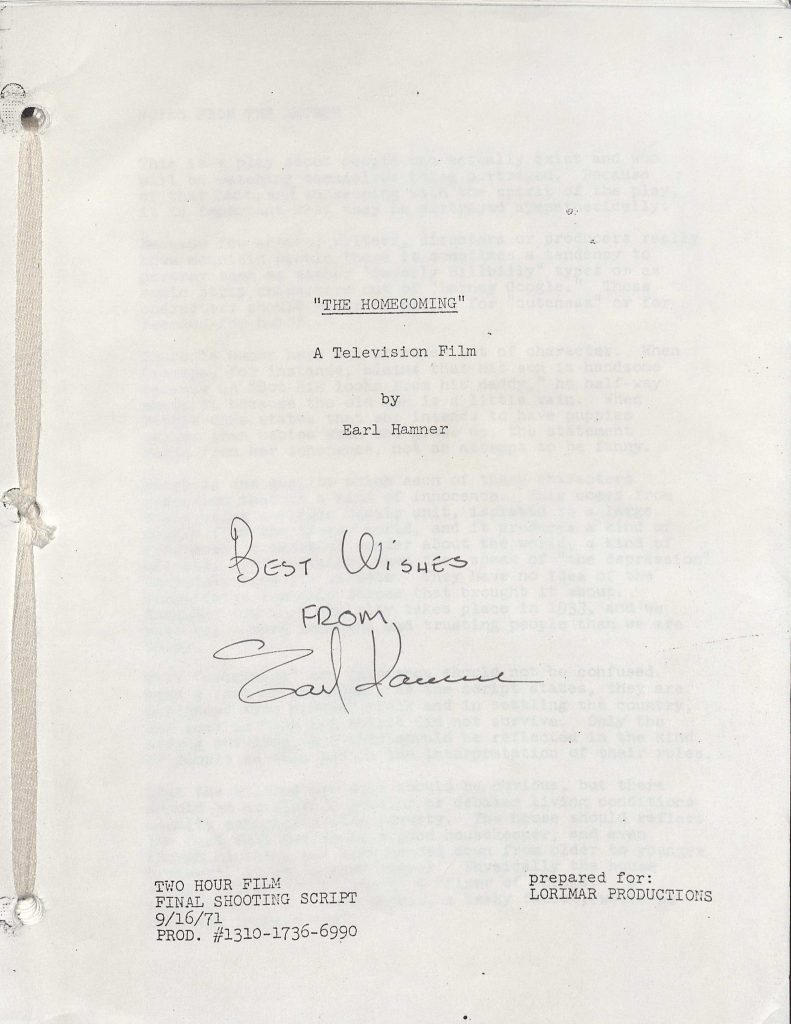

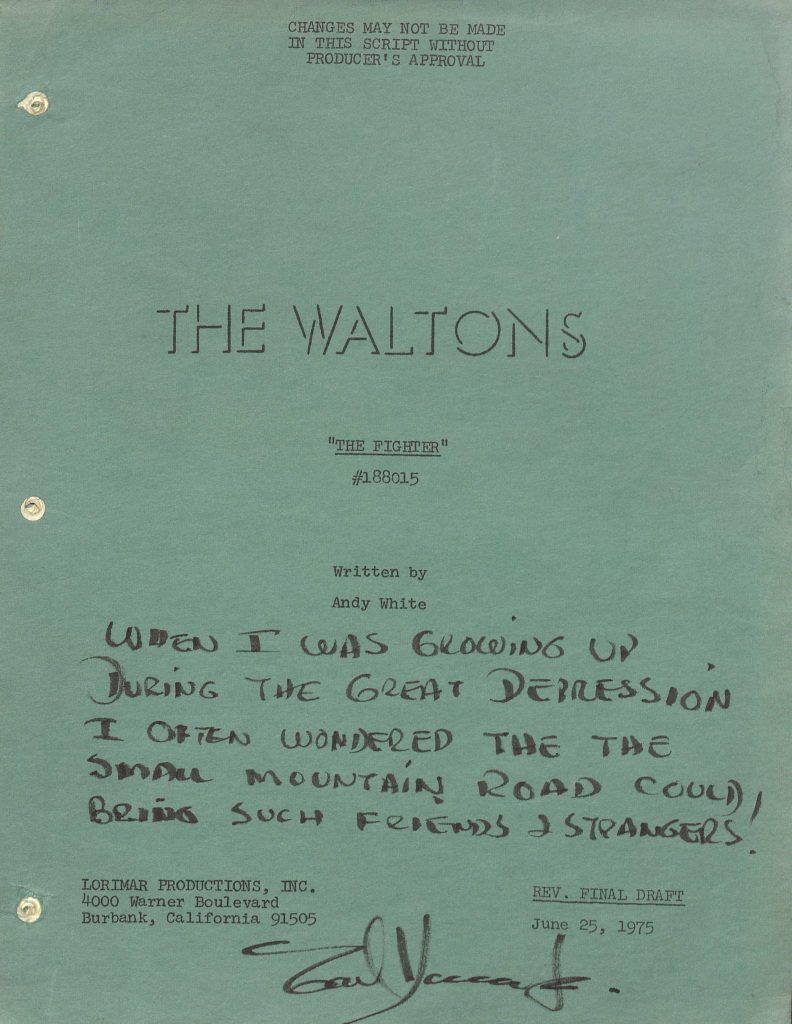

Shortly after I began looking into the Small Library’s treasure troves, I was delighted to discover that we hold a small but rich collection of Virginia native Earl Hamner Jr., an Emmy-winning television writer and director during the 1970’s and 80’s. The collection includes a first edition of Hamner’s 1970 novel, The Homecoming: A Novel about Spencer’s Mountain, the final shooting script for the 1971 film The Homecoming: A Christmas Story and television scripts for three mid-1970s episodes of The Waltons.

Earl Hamner, Jr. The Homecoming: A Novel about Spencer’s Mountain. (PS3558 .A456 H6 1970). The novel’s epigraph reads, “It is remembered in my family that Christmas Eve of 1933 my father was late arriving home. That, along with the love he and my mother bestowed upon their eight red-headed offspring, is fact. The rest is fiction.”

The novel, drawn from Hamner’s childhood experiences growing up in Schuyler, Virginia during the Great Depression, was the impetus for the film. Originally aired on CBS on December 19, 1971, the movie was so popular that it spun off a series, “The Waltons’, which aired on CBS in September 1972 and became wildly popular, lasting nine seasons.

Cover of the Final Shooting Script for the Lorimar Productions film “The Homecoming” (MSS 10380,-a,-b)

Cover of the television script for an episode of “The Waltons.” This is the revised final draft of episode #188015, “The Fighter” by Andy White (MSS 10380,-a,-b)

Christmas fans like myself know that the film that started the Waltons’ phenomenon is a holiday must-see. Included in the final script of the 1971 film ‘The Homecoming’ is a section entitled “Notes from the Author”:

[The] Christmas Season and Christmas has become a nightmare for most people. The packed stores, the enraged crowds, the stalled traffic and money worries that are common to our audience for the most part produce a national insanity. Yet underneath there is a pathetic wish that they can really experience something, maybe “The Christmas Spirit” something that no other time provides.

This holiday classic is a great start toward achieving that “Something.” So, shut out the madness of the holiday hustle and bustle. Pour yourself a BIG glass of egg-nog, get comfortable in your favorite chair and lose yourself in this wonderful coming-of-age Christmas classic. By the film’s end, I guarantee you will feel all warm and fuzzy inside (though that BIG glass of rum-infused egg nog may be partly responsible!). Wishing my colleagues and all the loyal readers of ‘Notes from Under Grounds’ a very safe and happy Holiday!

“Good Night, Penny”

“Good Night, Edward”

Good Night, David”

“Good Night, Heather and Gayle”

“Good Night George, Petrina, and Molly”

“Good Night E.J., Sharon, Ellen, Barbara, Jane…………”

Good Night, “Notes from Under Grounds” Readers!

Exhibition Prep Special: Translating Shakespeare’s Sonnets into…Morse Code?

This week we are pleased to feature the third guest blog post from graduate curatorial assistant Kelly Fleming, who will be sharing selected treats from our upcoming exhibition, “Shakespeare by the Book,” over the coming months. The exhibition opens February 22, 2016.

Most readers of Shakespeare’s sonnets associate his poetry with love. In films and literary works of all kinds, Shakespeare’s sonnets are quoted and used to confirm the love between two people. Sonnet 116 (“Let me not to the marriage of true minds”) is probably one of the most popular readings on the wedding circuit. As much as Shakespeare’s sonnets are about love, time is more likely to be the subject of the poet’s meditations. The first seventeen—“the procreation sonnets”—urge a young man to make much of time, to get married, and to procreate so that he can live forever through his children. Many of the sonnets after 17 continue to address, to personify, and to apostrophize time, as these first lines illustrate: “Against that time, if ever that time come” (Sonnet 49); “That time of year thou mayst in me behold” (Sonnet 73); “No, Time, thou shalt not boast that I do change” (Sonnet 123).

Knowing the sonnets’ preoccupation with time, I completely “nerded out” when I discovered that someone had turned Shakespeare’s sonnets into a watch. My own scholarship has nothing to do with Shakespeare, but every time Molly, our curator here at Special Collections, mentioned the watch to me, I would get so excited that I would say in a high-pitched voice, “But Shakespeare’s sonnets are all about time!” I cannot imagine a more perfect way to represent his sonnets than a watch.

The Sonnets Watch Book is book inside a watch; it is a watch that ticks out Shakespeare’s sonnet 18 (“Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”) and sonnet 130 (“My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun…”) in Morse code. It was dreamed up and built by three Seattle teenagers (credited on the watch as “Alex, Clara, and Nicholas”) and published by miniature-book publisher and technologist Robert Orndorff (who happens to be the father of two of the makers). Only eighteenth copies of The Sonnets Watch Book are in existence and number eighteen will appear in our exhibition. Bright lights flicker out the letters and punctuation marks of each sonnet. Even though I can’t understand Morse code, there is something incredibly moving about watching the lights change and knowing that Shakespeare’s words are still slowly being repeated throughout time.

Last week, I spent a full hour close reading Shakespeare’s Sonnet 65 and talking about time with my ENGL 3810 students. We were stuck on the following lines for a while:

O, how shall summer’s honey breath hold out

Against the wreckful siege of battering days,

When rocks impregnable are not so stout,

Nor gates of steel so strong, but Time decays?

Shakespeare’s answer to this question is his sonnet. Unlike the sea, stone, or shining metals, his “black ink” may be able to withstand the rages of time. His “black ink” will continue to “shine bright” and tell of his love. As my students will tell you, this is exactly what happened. We spent twenty-five minutes of our class on four lines because his “black ink” does still “shine bright” in the history of literature.

Imagine, then, an object that literalizes the hope, the wish of this sonnet. Shakespeare’s words, his “black ink,” actually “[shining] bright” in little yellow, green, and red blinking lights on the face of a watch.

Now, who is excited?

Click on the link below for a video of the watch in action and proof that Shakespeare’s sonnets are now more portable than ever before. The Sonnets Watchbook will be on view—alive and ticking—in “Shakespeare by the Book: Four Centuries of Printing, Editing, and Publishing,” which runs February 22-December 2016 at the University of Virginia Library.

Oh, and in case you are wondering about the history of literature translated into code, perhaps you would like to see Monty Python’s take on the topic. They start with Wuthering Heights and go on from there…make sure to stay to the end!:

Exhibition Prep Special: Searching for Shakespeare in Booksellers’ Records

This week we are pleased to feature the second guest blog post from graduate curatorial assistant Kelly Fleming, who will be sharing selected treats from our upcoming exhibition, “Shakespeare by the Book,” over the coming months. The exhibition opens February 22, 2016.

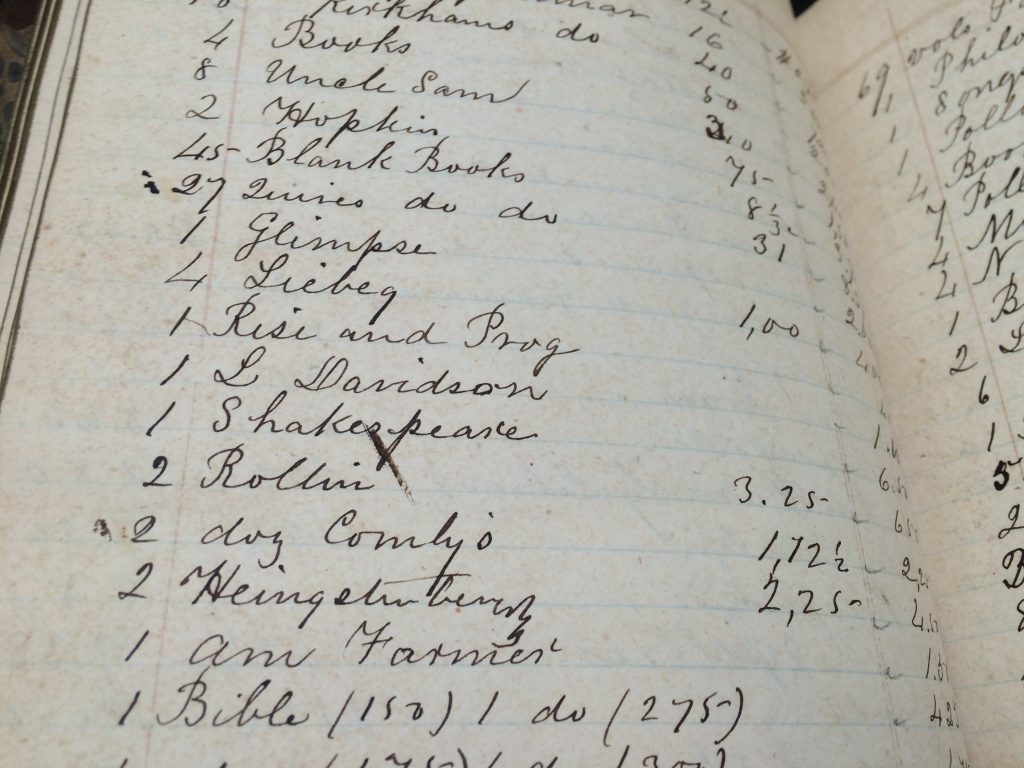

My first two weeks at Special Collections were spent hoisting hulking ledgers from the stacks and placing them gently onto cradles to investigate whether two early booksellers in Virginia sold Shakespeare. After the first day, I found my legs covered in wisps of binding and my hands stained with “red rot” from the ledgers’ leather bindings. Thank goodness for gloves.

Here’s what my gloves looked like after several ledgers. Imagine what my bare hands looked like before I put them on.

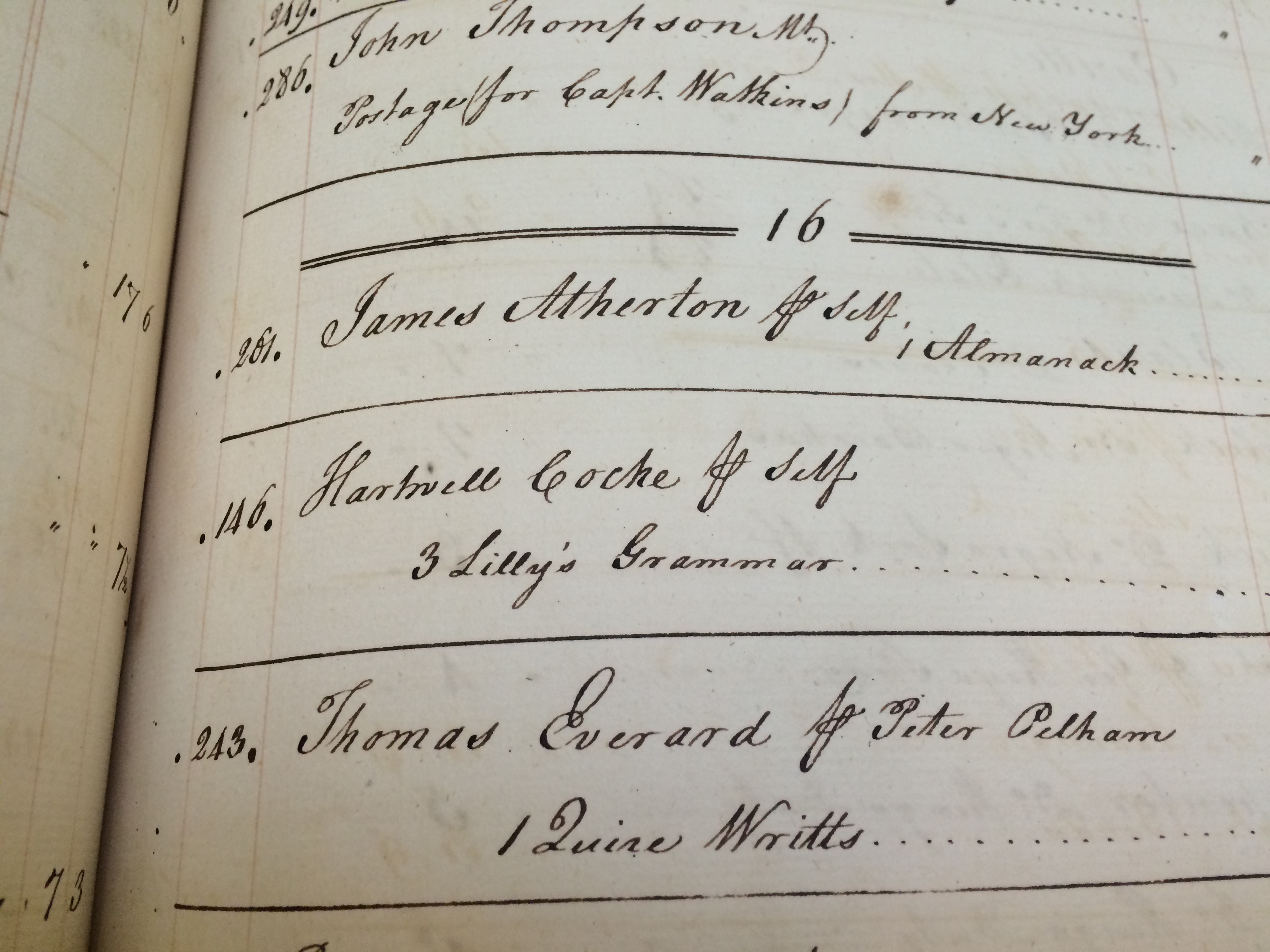

I combed through the account books of Bell & Co., a printer in Alexandria, Virginia active in the nineteenth century and the Virginia Gazette, a newspaper and printer active in Williamsburg, Virginia in the eighteenth century. My eyes sought any spelling variation of the name “Shakespeare” amidst endless purchases of envelopes and paper. Despite our modern perception that Shakespeare’s works are “classics” and that he is a father of the English language, his place in the literary canon was yet to be defined in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. As my findings attest, Virginians chose to read a myriad of other things more frequently than Shakespeare.

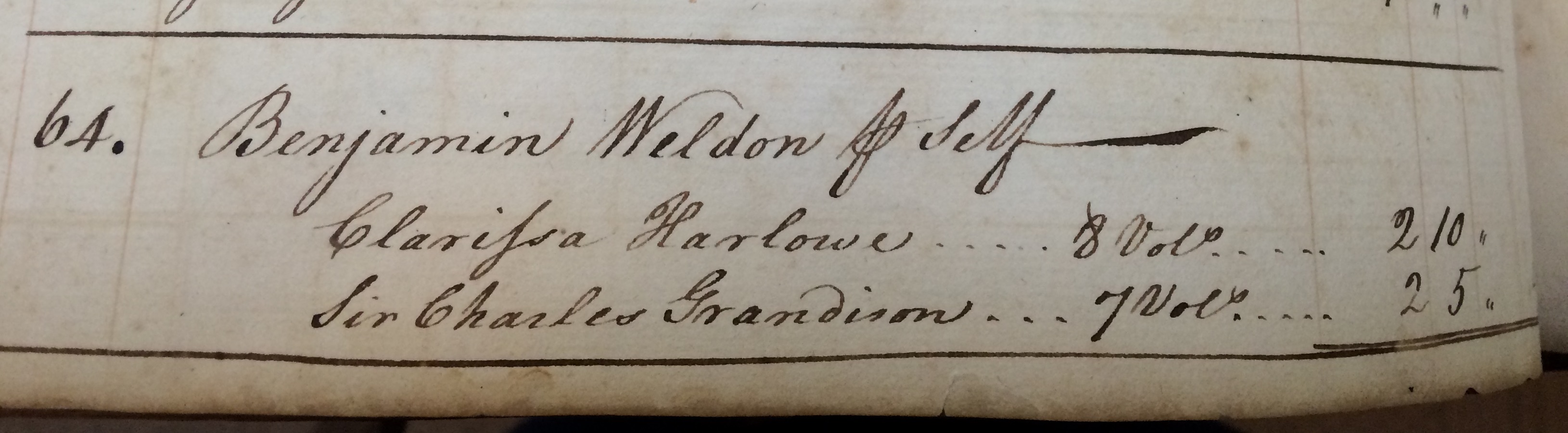

Only one copy of Shakespeare was sold by the Virginia Gazette in the years 1750–1752 and 1764–1766. Even though David Garrick was busily working to increase the popularity of Shakespeare in London at this time, the colonies seem to have been a step behind. Since Williamsburg was home to the Virginia legislature and the College of William & Mary, it is not surprising that the books sold by the Virginia Gazette were largely educational: Latin grammar textbooks, dictionaries, and religious texts like the Book of Common Prayer. Despite the fact that Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (a book the Virginia Gazette also sold) marks Shakespeare’s works as the first usage of many English words, students were not studying Shakespeare. The education system in the eighteenth century trained students (that is to say, young men) in what they considered the “classics”: philosophical and literary texts from ancient Greece and Rome. When students did read literary texts in English, it seems that they read English epics, which use classical elements to describe contemporary England. The epic works of Milton, Dryden, and Pope, for example, appear numerous times in the accounts of the Virginia Gazette. In addition to English epics, we find our copy of Shakespeare alongside another genre excluded from the education system: the novel. In the ledger in our exhibition, we find popular English novels such as Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa and Tobias Smollett’s Roderick Random.

![Joseph Hutchings purchased 8 volumes of of Shakespeare "for [his] self" (MSS 467).](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/theobalds_shakespeare.jpg)

The Virginia Gazette records show Joseph Hutchings purchasing 8 volumes of Shakespeare “for [him] self” (MSS 467).

Alongside Shakespeare in the Virginia Gazette records are two of Samuel Richardson’s novels, “Clarissa: Or, the History of a Young Lady” (1747-8) and “The History of Sir Charles Grandison” (1753). (MSS 467)

Alongside Shakespeare in the Virginia Gazette records are many educational texts such as Lilly’s Latin Grammar. (MSS 467)

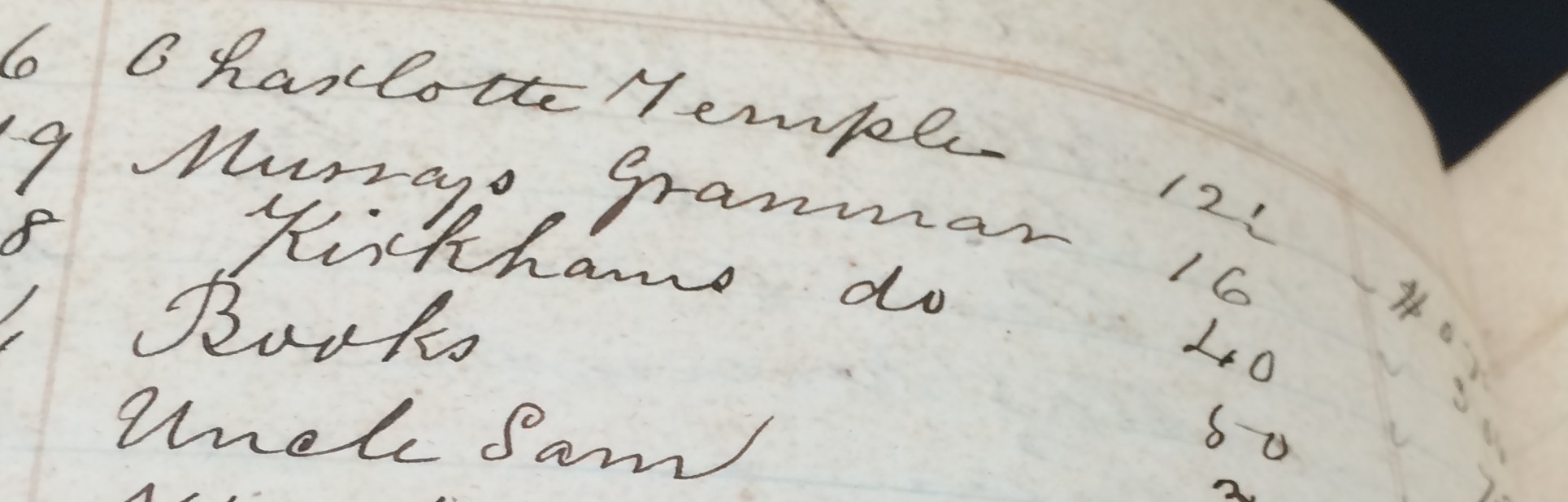

Thanks largely to new performances of Shakespeare plays, Garrick’s Shakespeare Jubilee, and new editions of Shakespeare works in the eighteenth century, Shakespeare’s words come alive by the nineteenth century. The accounts of Bell & Co. reflect this increasing popularity. I found seven copies of Shakespeare sold at Bell & Co. over the course of the nineteenth century (1809–1899). The specific ledger we are using in the exhibition shows Shakespeare alongside Susanna Rowson’s novel Charlotte Temple, Wordsworth, Cooper’s Virgil, and the Bible.

Bell & Co. sold Shakespeare for “6.50.” Different types of currency were in use in the colonies at this time. Without further research, all we can tell from this record is that it is expensive and suggests that the reader bought a multi-volume set (MSS 2989).

On the same page as Shakespeare, Bell & Co. recorded the purchase of Susanna Rowson’s novel “Charlotte Temple” and two grammar books. (MSS 2989)

Finally, in the twentieth century, Shakespeare begins to be studied and to be studied as a father of the English language. Today, Shakespeare is probably the most often memorized, most often recited English author in schools. I still can recite the famous speech of Titania’s from A Midsummer’s Night Dream that I memorized in the tenth grade and that begins “Set your heart at rest.” But as the exhibition at the Special Collections Library will show us in February, our hearts do anything but rest when we hear the heartbeat of Shakespeare’s iambs, even four hundred years after his death.

Lafayette at U. Va.

This summer the French frigate Hermione—a reconstruction of the vessel which, in 1780, brought the Marquis de Lafayette back to the United States with welcome news of French aid, and which then helped to secure final victory at Yorktown in 1781—made a triumphal voyage to the United States. Built in France between 1997 and 2012 at a cost of over $20 million, the Hermione—measuring 213 x 37 feet, its center mast reaching 177 feet—takes pride of place as France’s grandest “tall ship.” After arriving at Yorktown, Va., to a gala reception on June 5, the Hermione stopped at a dozen ports of call along the eastern seaboard before departing for France on July 18.

As a memento of the Hermione’s visit, the U.Va. Library’s devoted friend and generous supporter Albert H. Small has presented us with a photograph of the reconstructed ship at anchor in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. Mr. Small’s gift prompted us to search Under Grounds for rare books, manuscripts, and other artifacts relating to Lafayette, and we located much of interest! Following is a brief sampling of what Lafayette enthusiasts will find in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

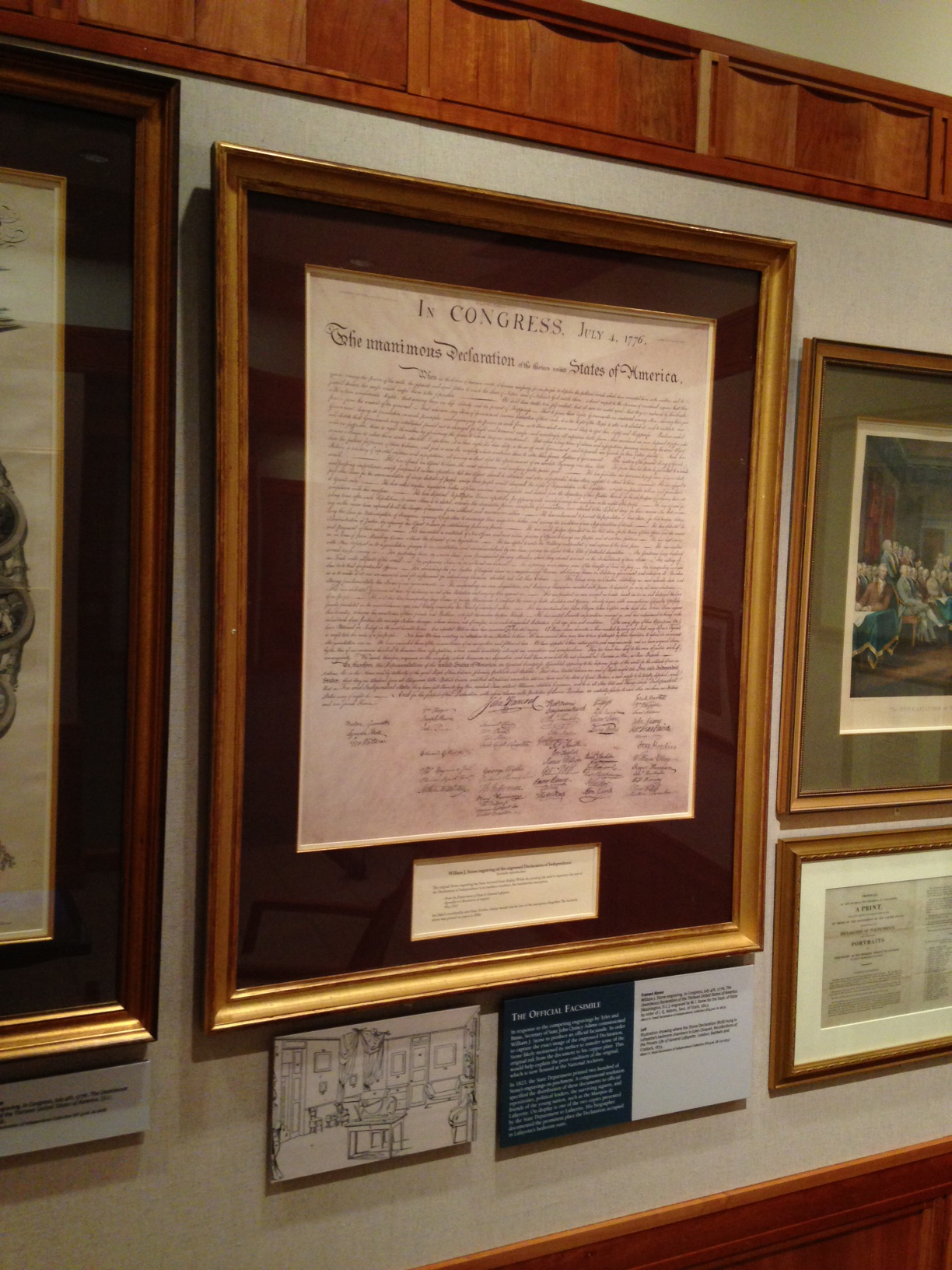

The Marquis de Lafayette – Albert H. Small copy of the 1823 “Stone” facsimile of the Declaration of Independence, on display in the Small Special Collections Library’s Declaration Exhibition Gallery. (KF4506 .A1 1823; Gift of Albert H. Small)

Perhaps pride of place should go to Lafayette’s own copy of the Declaration of Independence—the document he devoted his life to defending and disseminating. During Lafayette’s triumphal tour of the United States in 1824-1825, he was presented with an official full-size engraved facsimile, printed on vellum, of the original Declaration now on display in the National Archives. Lafayette treasured this copy of the “Stone printing,” hanging it in his bedchamber after returning to France. Eventually acquired by Albert H. Small, Lafayette’s copy now resides at U.Va., where it forms part of Mr. Small’s superlative Declaration of Independence collection. Visitors may view it (or rather, for conservation reasons, an exact facsimile of the original) in the Small Special Collections Library’s permanent exhibition of highlights from Mr. Small’s collection.

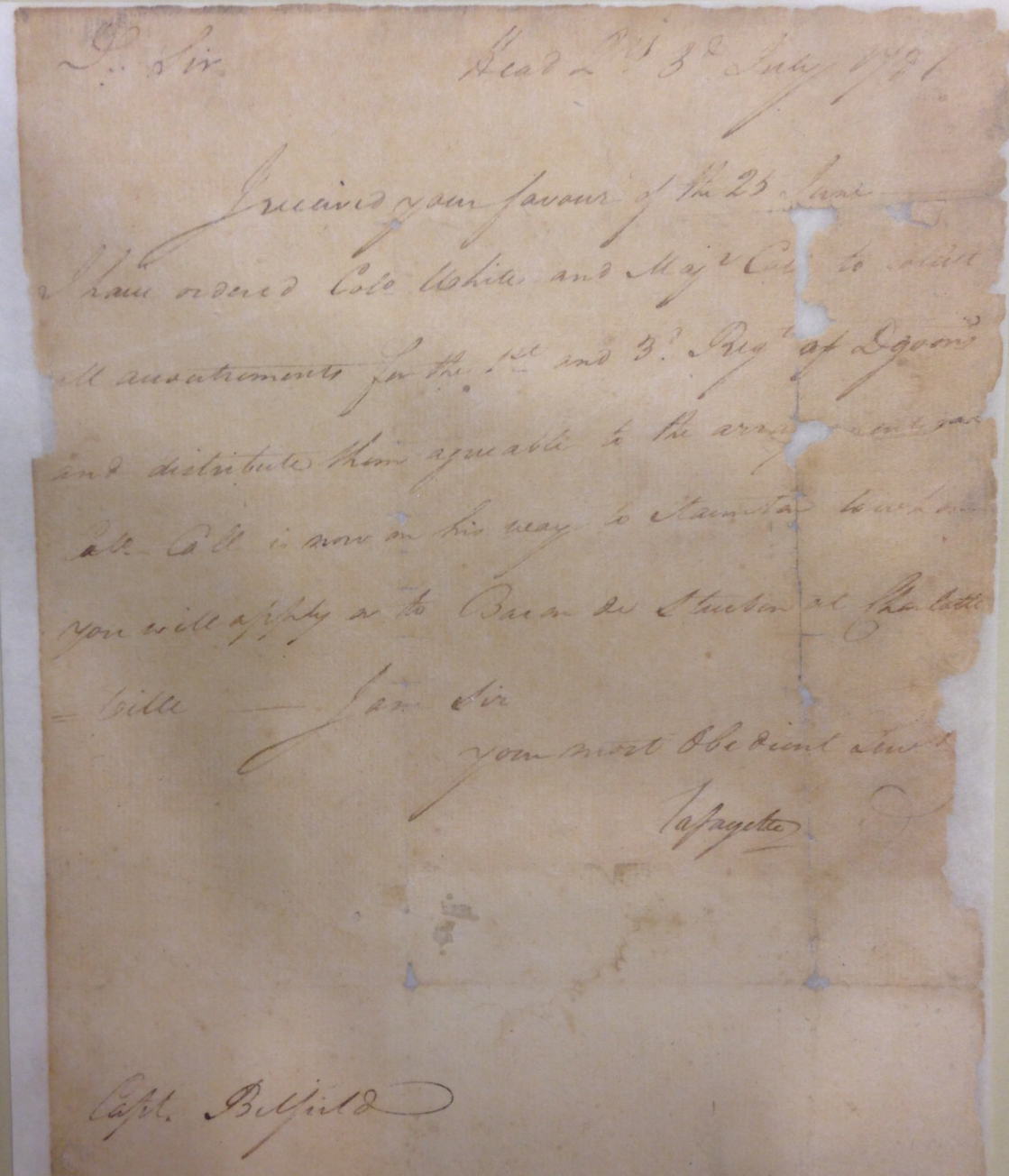

Arriving in the U.S. in 1777 as a newly commissioned officer, the 19-year-old Lafayette soon won the respect and friendship of George Washington while contributing significantly to the American cause. In the early summer of 1781, Lafayette played a critical role in skirmishing with British forces in Virginia until Washington had time to spring his trap at Yorktown. On July 3, 1781, Lafayette sent the orders shown above to a Capt. Belfield at Staunton, Va., also noting the presence of Baron von Steuben in Charlottesville.

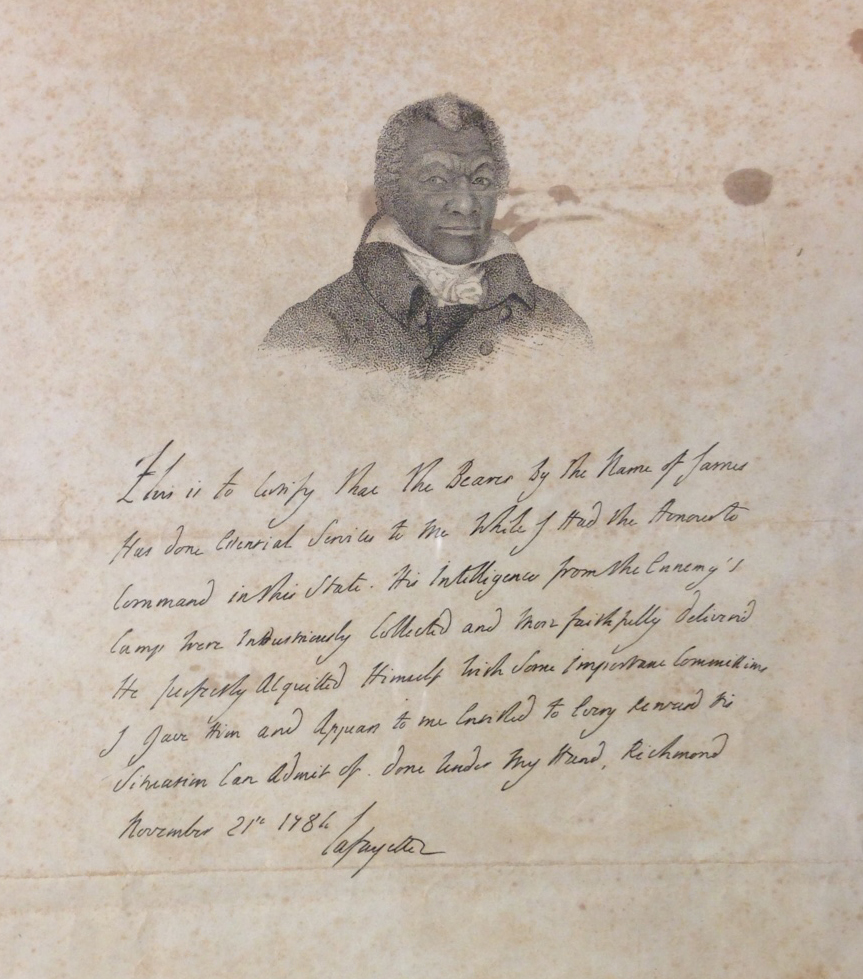

An engraved facsimile, ca. 1824, of Lafayette’s 1784 testimonial letter on behalf of James Armistead Lafayette, with added portrait. (Broadside 1824 .L25)

Another Virginian in Lafayette’s service was James, a slave permitted by his master to serve as an American spy behind British lines by posing as a fugitive. In 1787, with his owner’s support and a testimonial letter from Lafayette, James was freed by the Virginia Assembly and took the name James Armistead Lafayette. When Lafayette returned to the U.S. in 1824, his kindness to James—and his ardent support for the as-yet-unrealized ideal that “all men are created equal”—were commemorated in an engraved print bearing James’s likeness above a facsimile of Lafayette’s testimonial letter.

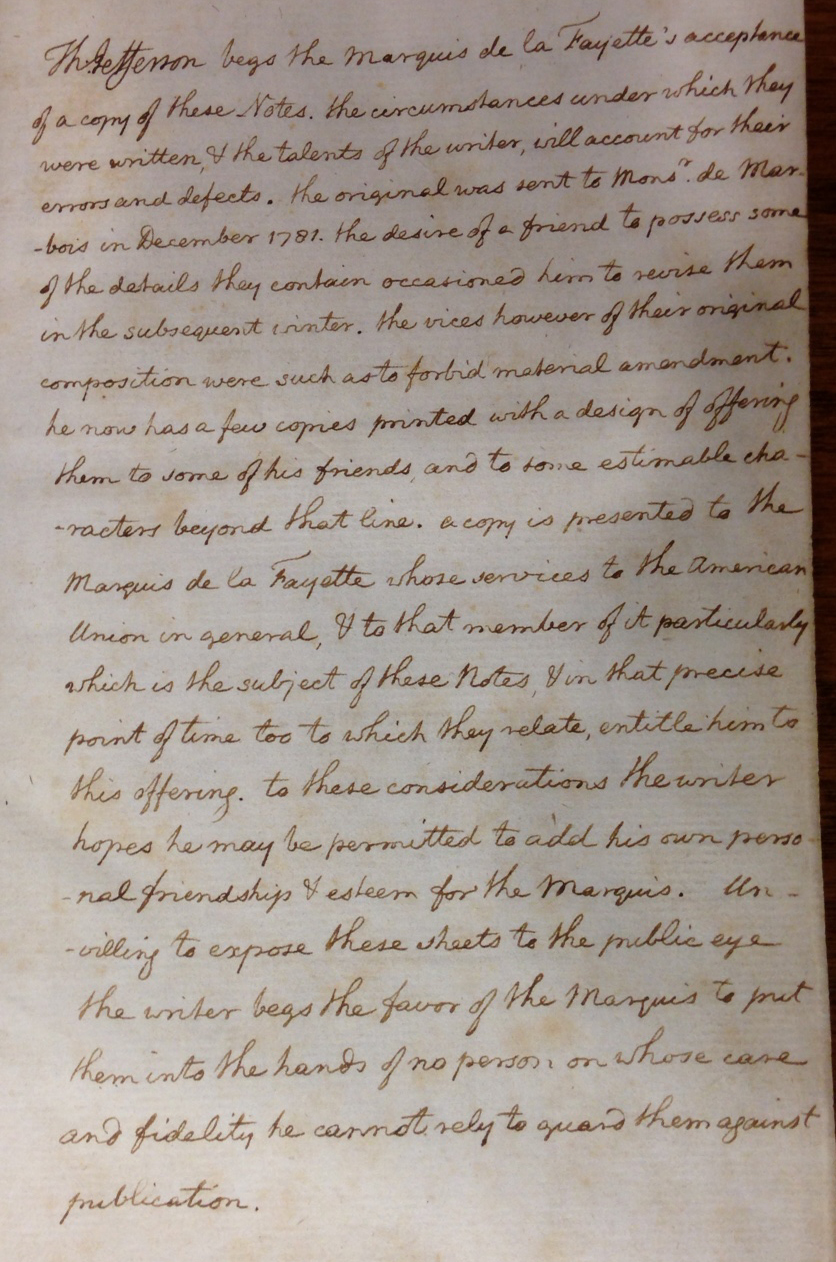

Jefferson’s presentation inscription to Lafayette in a gift copy of Notes on the State of Virginia (Paris, 1784-1785). (F230 .J4 1785; Gift of William Andrews Clark, Jr.)

While James sought his freedom another Virginian, Thomas Jefferson, was in Paris, where he arranged to print 200 copies of his book, Notes on the State of Virginia, during 1784-1785. These he privately distributed as he saw fit on both sides of the Atlantic. To a small number of specially bound presentation copies, including one sent to Lafayette, Jefferson added long, personal inscriptions. Lafayette’s copy now resides at U.Va., the gift of William Andrews Clark, Jr.

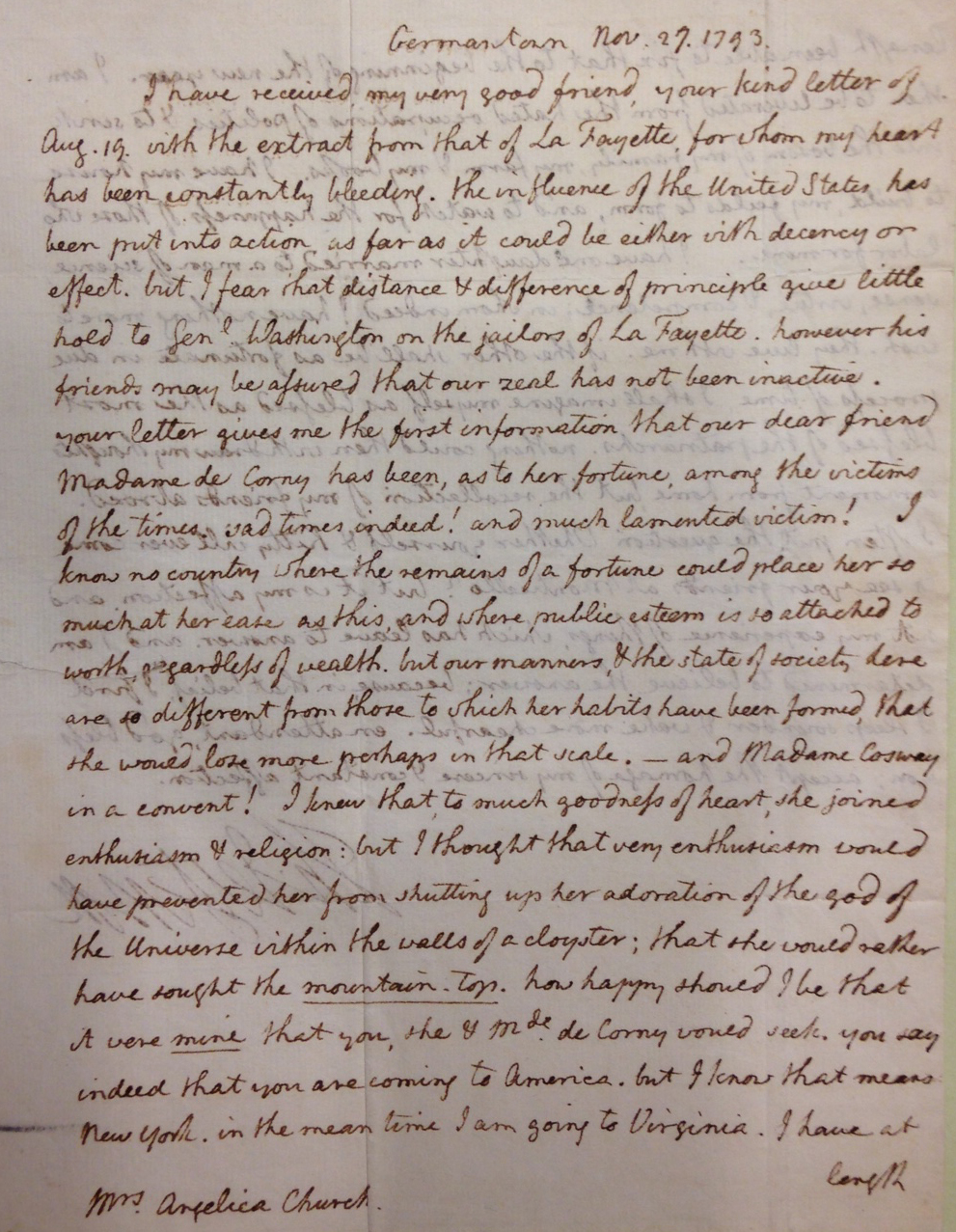

Thomas Jefferson’s letter of November 27, 1793 to Angelica Schuyler Church, in which he discusses American efforts to free Lafayette from a French prison. (MSS 11245-b)

Among the many friendships Jefferson cultivated in Paris was that of American expatriate Angelica Schuyler Church, wife of an American diplomat and Alexander Hamilton’s sister-in-law. Church later moved to London, where she monitored with increasing dismay the unfolding French Revolution and its tragic consequences for her friends. In her unceasing efforts to aid one imprisoned friend—the Marquis de Lafayette—Church was ultimately successful, as documented in an extraordinary cache of correspondence obtained by U.Va. a few years ago. Included is a 1793 letter from Jefferson, then Secretary of State, who thanks Church for forwarding a letter from “my very good friend” Lafayette, and informs her that “the influence of the United States has been put into action as far as it could be either with decency or effect.” (Sharp-eyed readers will also note a fascinating reference to Maria Cosway.)

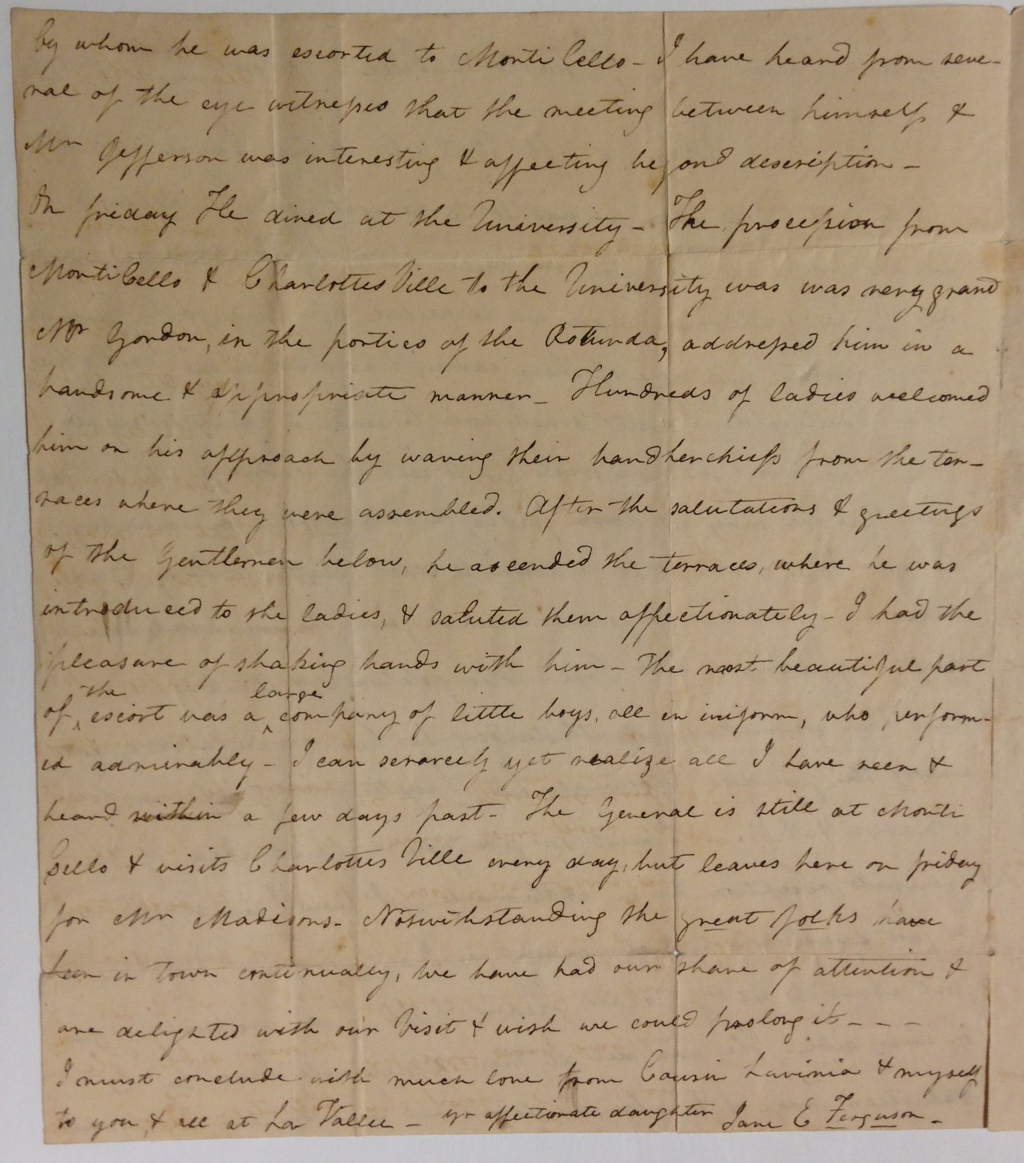

Most of our Lafayette holdings, however, relate to his extended American tour, from July 1824 to September 1825, during which he received the proverbial hero’s welcome from Americans in 24 states. In Special Collections one will find a diverse assortment of primary sources documenting Lafayette’s American travels, ranging from commemorative silk ribbons worn in his honor to eyewitness accounts of local festivities in letters sent to friends and family. From November 4-8, 1824, Lafayette was in Charlottesville where, after an emotional reunion with Jefferson at Monticello, Lafayette was fêted at a banquet held in the still-unfinished U.Va. Rotunda. Many interesting details of the event were conveyed in this letter from local resident Jane E. Ferguson to her father.

Jane E. Ferguson’s account of Lafayette’s reception at the U.Va. Rotunda on November 8, 1824. (MSS 38-122-a)

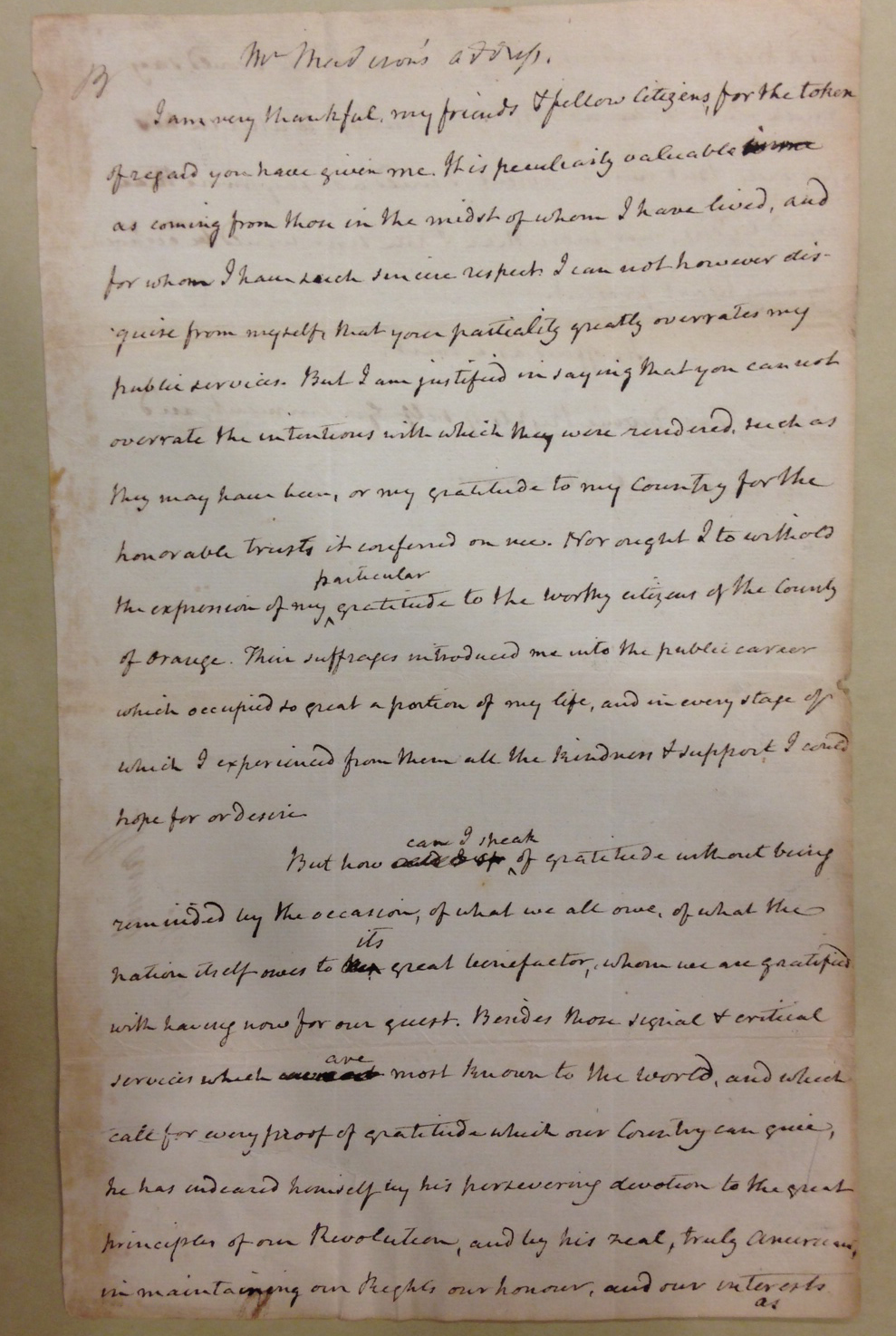

From Charlottesville Lafayette journeyed overland to Orange, Va., where on November 25, 1824, he was received with great ceremony. Making the public introduction was former president (and local resident) James Madison, whose remarks are preserved in the holograph draft to be found in the Small Special Collections Library.

James Madison’s remarks introducing Lafayette to the citizens of Orange, Va., November 25, 1824. (MSS 4677)

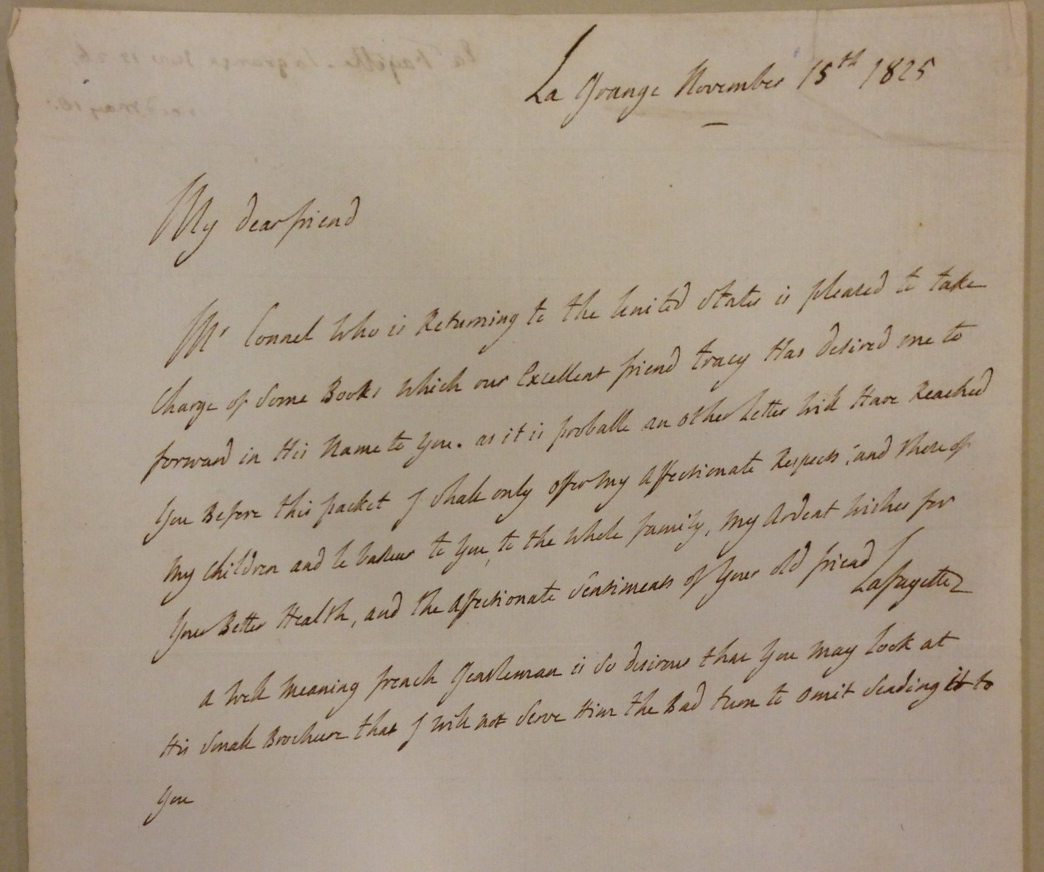

Nearly a year later Lafayette was back in France. On November 5, 1825, Lafayette wrote to Jefferson from his home in La Grange, advising him of a shipment of, what else but books, and sending “my ardent wishes for your better health, and the affectionate sentiments of your old friend.” On the reverse Jefferson noted the letter’s receipt at Monticello on May 18, 1826—perhaps the final communication he would receive from Lafayette.

Collecting History in Real Time

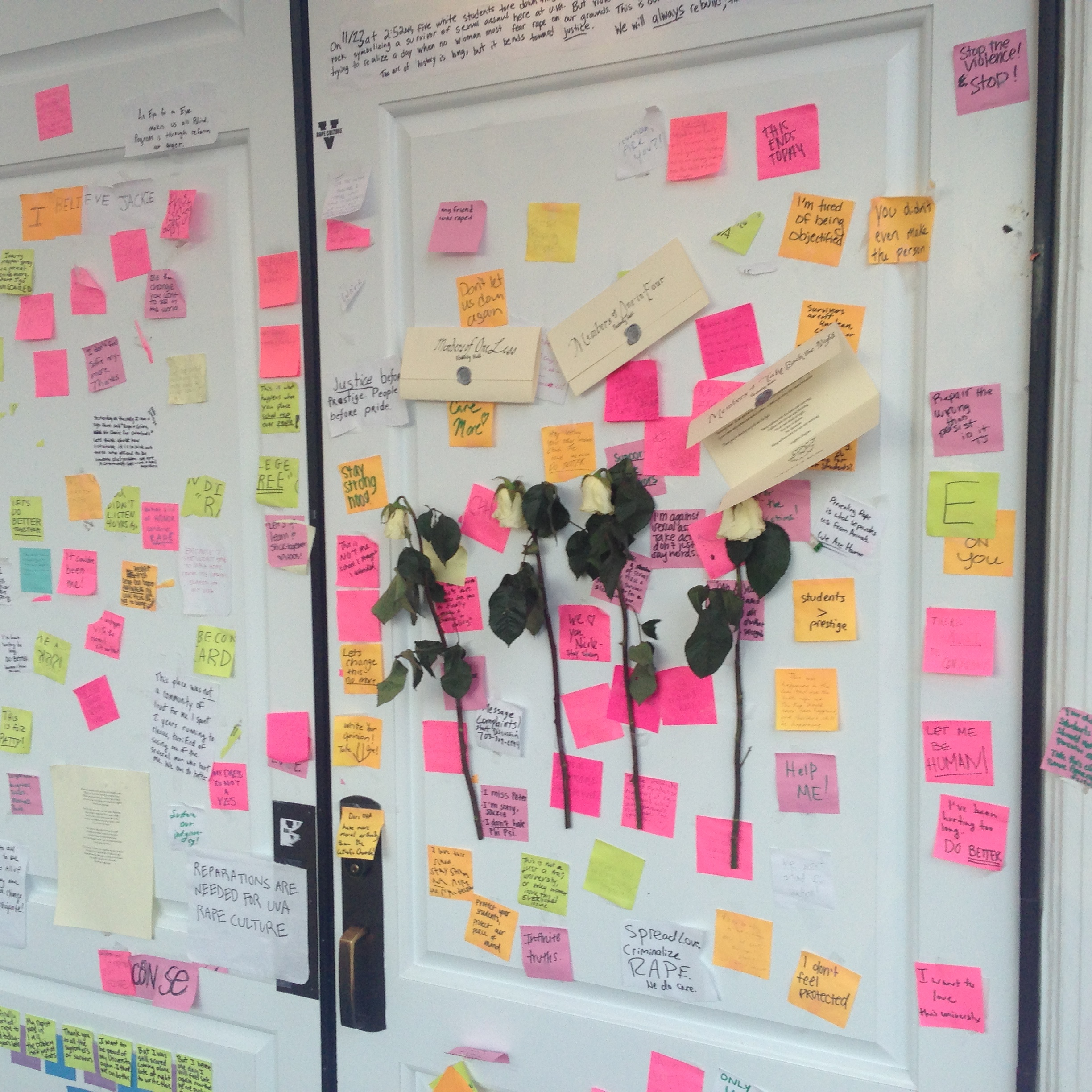

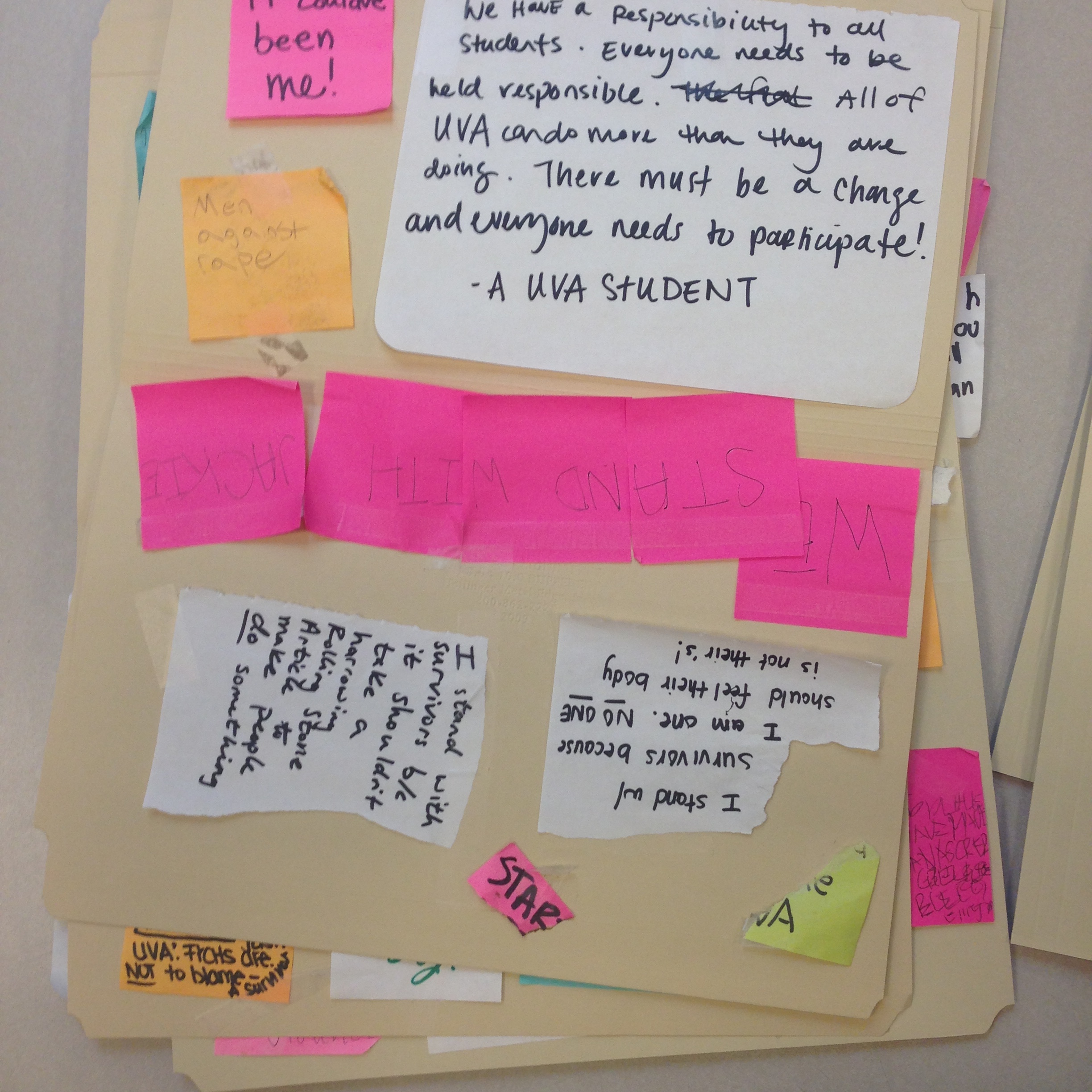

As early as November 21st, a spontaneous display of notes, supporting rape survivors and expressing grief and anger, began appearing at the entrance of Peabody Hall, home of the Office of the Dean of Students and Undergraduate Admissions. The display was the result of the controversial Rolling Stone article, “A Rape on Campus: A Brutal Assault and Struggle for Justice at UVA” by Sabrina Rubin Erdely.

Staff at special collections and archives across the country, including the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, have become increasingly active in collecting material, ephemeral and otherwise, born out of crises that have rocked their communities. These records–be they notes, flowers, posters, photographs, poems, press releases, online articles, etc.–help to document and provide insight into the actions, reactions, and emotions of the people, institutions, and their associated communities as they are impacted by each wave of the event. We know from experience that our own students and faculty are deeply interested in researching events from the university’s past, distant and recent alike, and we want to ensure that we can provide future generations with a rich record of our present.

During U.Va. finals week, the Dean of Admissions contacted Library Administration, who in turn contacted Special Collections staff, to start the process of removing the notes for permanent preservation. On Wednesday of finals week, Librarian for Virginiana and University Archives Edward Gaynor and Rare Books Cataloger Gayle Cooper removed the notes and other ephemera from the doors and brought them to Special Collections.

To get the materials researcher-ready, staff had to answer questions, like “How do you preserve it?” and “How do you capture something so ephemeral?” The first step was to temporarily house them by sticking them to archival folders.

Notes from the Peabody Hall door, temporarily housed on archival folders, 10 December 2014. (Photograph by Edward Gaynor)

The second step was to consult Library Conservator Eliza Gilligan for guidance in permanently housing and treating the items. She suggested transferring the notes to pieces of archival mat board cut to the size of our standard document box, and then shelving them in the University Archives. She recommended methyl cellulose as the adhesive and determined that placing each piece of mat board in a labelled folder would best support later scanning, display, and researcher use. What about the flowers? They will be freeze-dried in the Preservation Department’s freezer.

Now that the preservation and housing methods have been decided upon, our manuscripts and archival processing staff will begin arranging and describing the notes so that they will be fully processed and accessible to the public spring semester 2015.

***

Do you have fliers, posters, signs, or other materials related to the current events surrounding sexual violence at U.Va.? If so, please consider donating them to Special Collections. Just drop them by the reference desk, or contact Edward Gaynor at efg2f@virginia.edu.

Sugar High: A Curator’s Halloween Musings

In the throes of a pleasant candy-corn headache the other day, I wondered what we should post to the blog in celebration of tomorrow’s big holiday. What does the library hold related to candy, I wondered? So I opened Virgo, put on my headphones and hit play. On deck was the Flaming Lips’ cover of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album. Research always benefits from an apt soundtrack, and this over-the-top techno-celebration suited my purposes.

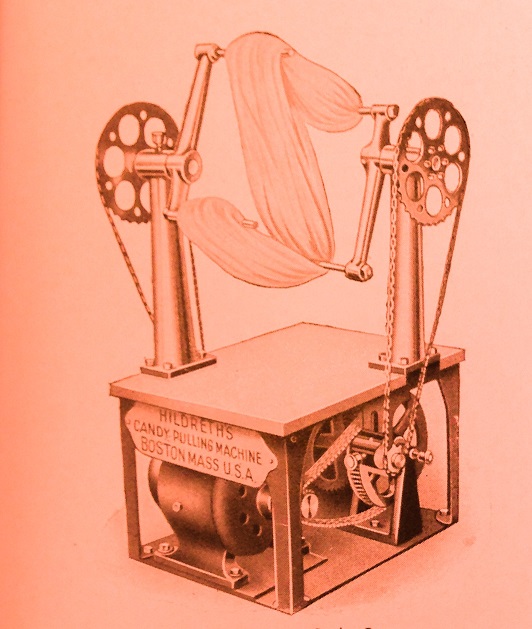

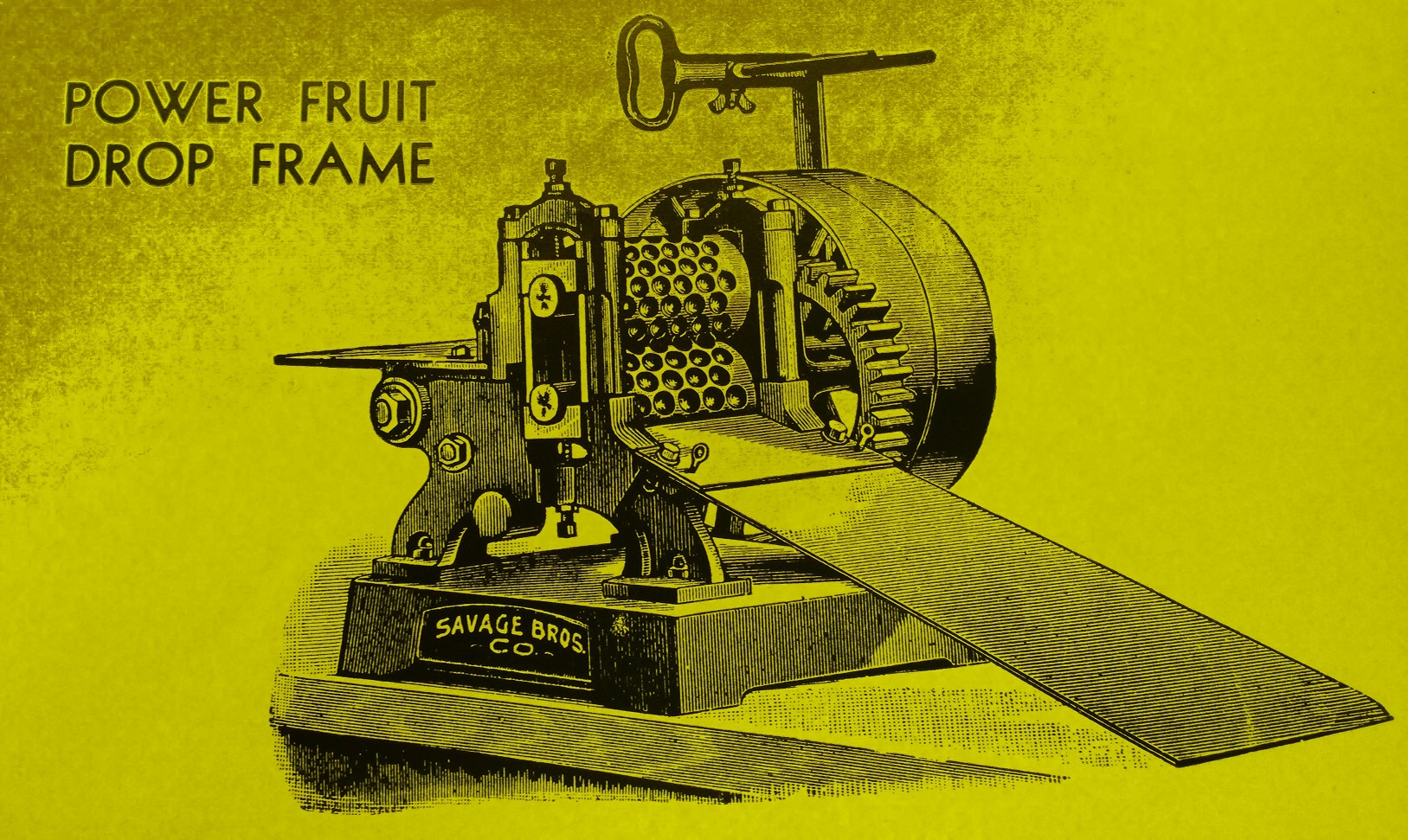

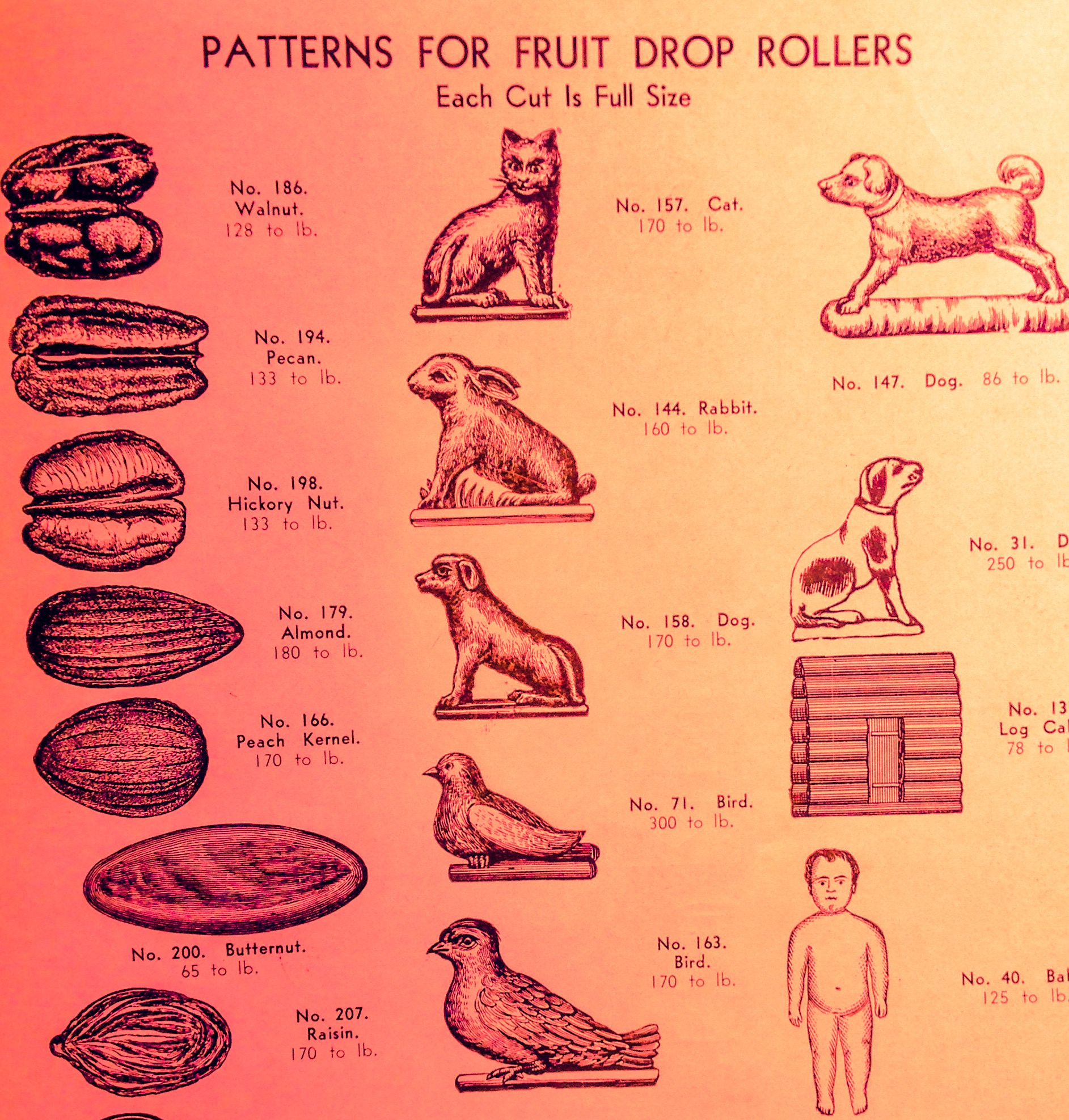

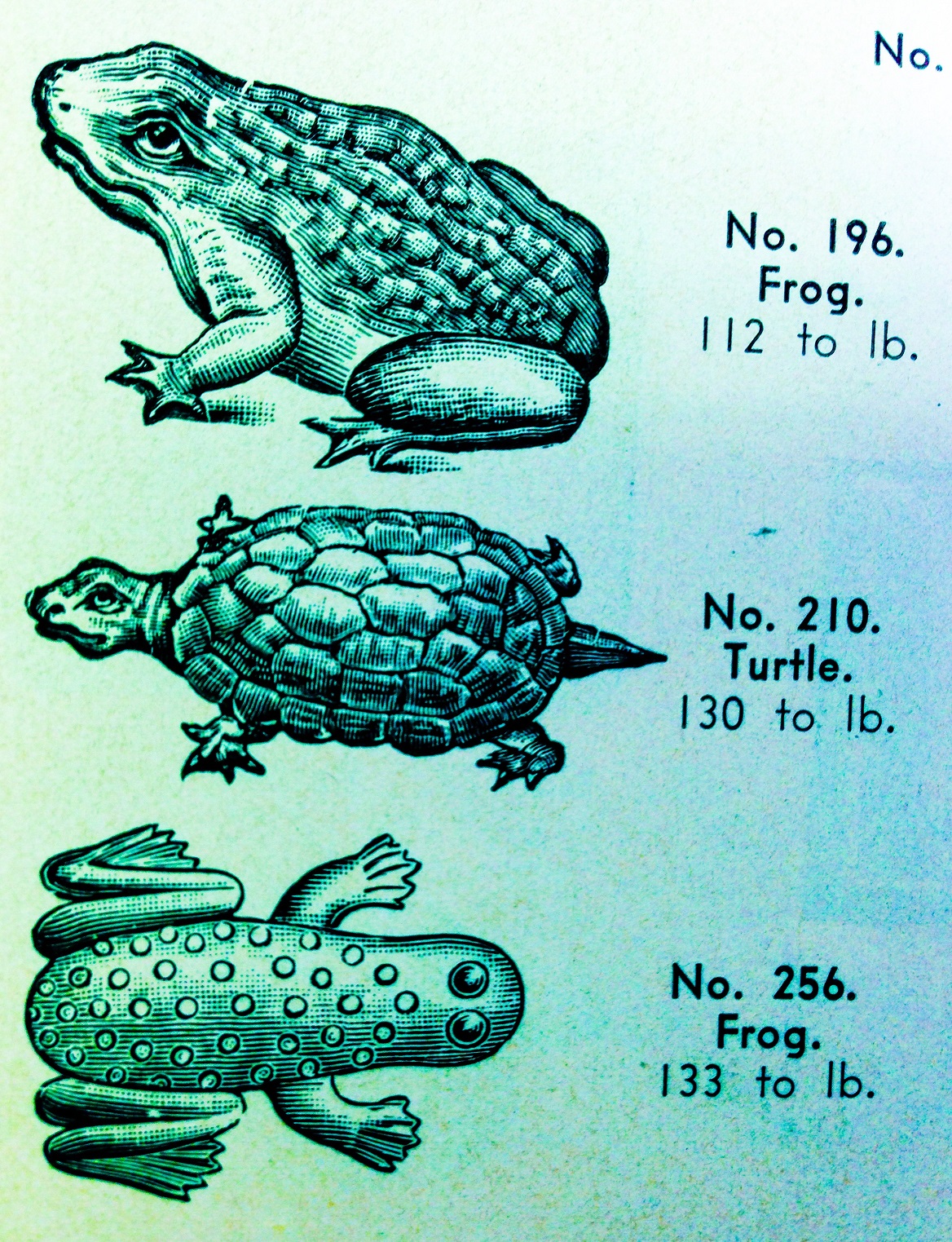

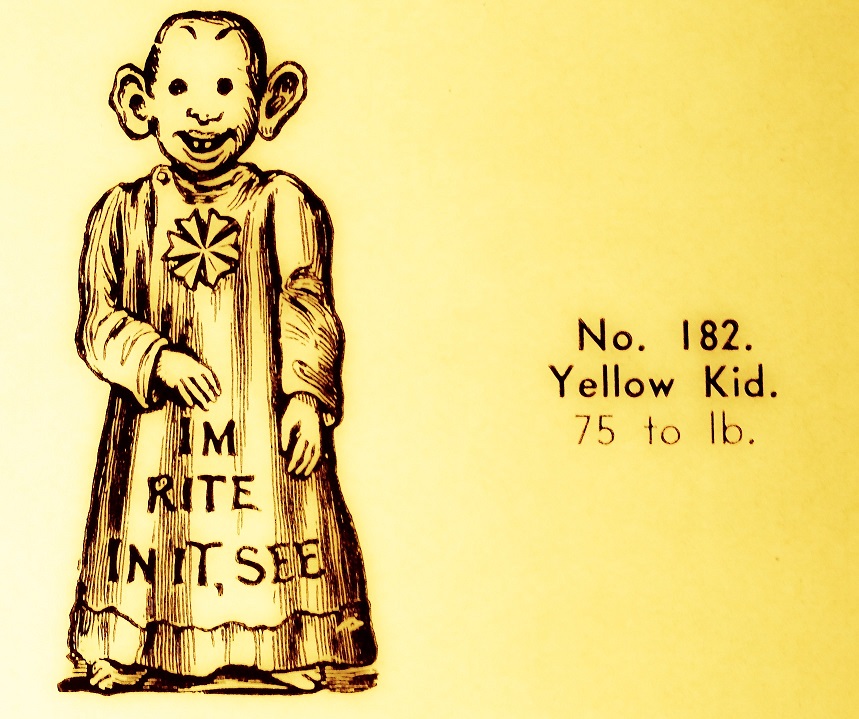

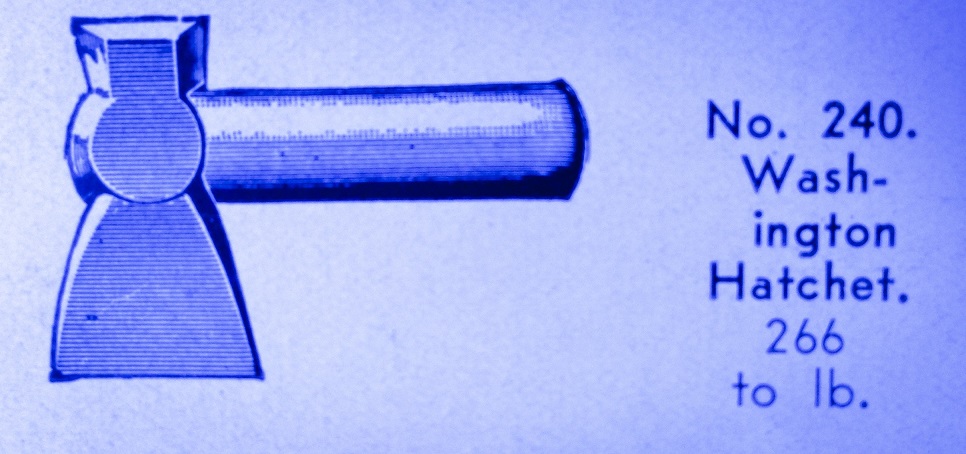

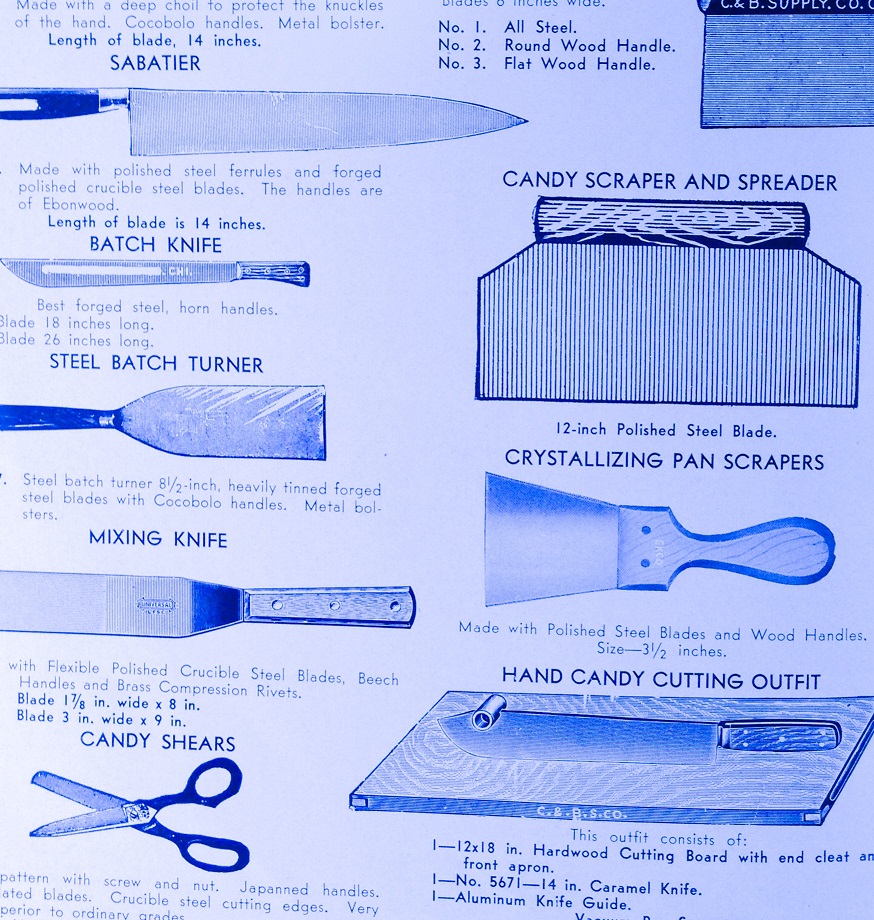

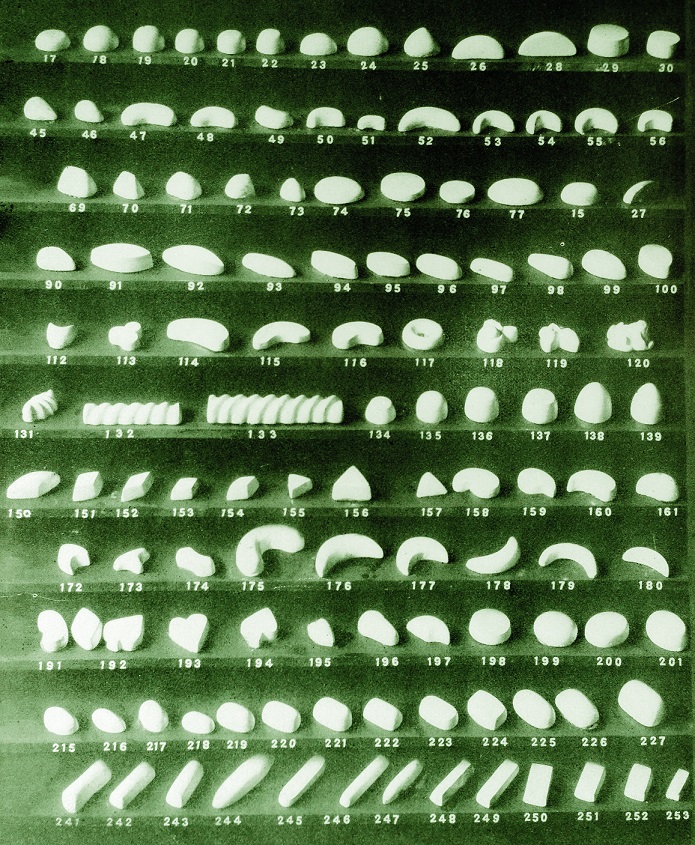

With a list of possible items in hand, I wandered the stacks, wishing I had a stash of Junior Mints in my pocket for this journey (but never fear, even Junior Mints cannot tempt me to break our no-food-in-the-stacks rule). Among the treasures I discovered, one in particular made my tastebuds buzz: a turn-of-the-century trade catalogue of the Savage Bros. Co., a Chicago manufacturer of candy-making machines since 1855 (They’re still in business today!). Enjoy the following selection of images (preferably while consuming something terribly bad for you) and have a happy Halloween!

Ah, pulled taffy. Who hasn’t enjoyed the unique pleasure of stumbling across one of these machines in action in an olde candy shoppe in a seafront or mountain resort area? Truly, only the Zamboni exceeds it in mesmeric power. Note the manufacturer name on the image here: perhaps Savage Bros. distributed this east-coast product to the Midwestern market.

Fruit-drop candy machinery is well-represented in the catalog, and this example clearly reveals the production method. Sugary goodness goes in on the left as the two rolls turn, popping out shaped candies on the other side, which roll down the plank, cooling as they go. Yum.

This alphabet fruit-drop roller mechanism is DIVINE! What bibliophile wouldn’t want to receive a gift of a bag of alphabet candies?

Few things are as creepy as baby dolls that have the faces of adults. But I think maybe baby candy with this problem is creepier.

The catalog makes me want to take up candy-making. These tiny creatures would make wonderful Halloween treats, especially if they were made in a creepy brownish-green. Deeeeee-licious!

There was even a fruit-drop mold for the Yellow Kid, a popular cartoon character of the period. Seventy-five of this odd little figure could be rolled out of a pound of sugary goodness.

Hundreds of fruit-drop patterns were available to the Savage Co.’s customers, including odd ones like this Washington Hatchet. Somehow, I can’t quite imagine wanting to suck on a hatchet blade. But now that I think of it, there would be something very halloweeny about it, wouldn’t there? Puts a whole new twist on the whole razor-blade Halloween paranoia…

Speaking of blades, all sorts of candy-making hand tools are available in the catalog, alongside large and small industrial machines.

These lovely “plaster paris starch moulds” resulted in highly detailed shaped bonbons. No candy corn shape, alas. Savage only offered molds for an entire ear of corn.

Some products feature factory workers for scale. Here, a woman places pans of chocolate candies in a cooling cabinet; a block of ice is visible in the open door on the left. Maybe I’ll dress as her for Halloween next year.

Blogger’s note: all images have been shamelessly cropped and altered for full sugar-high effect. No images are left unscathed. To view the book in its original condition, request TS199 .A5 H4 no. 24 in the Special Collections reading room. As always, please wash your hands of all candy residue before entering the reading room.

Finding Humanity in the Past

This week, we are pleased to feature a guest post by Gayle Jessup White, who is a Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies Fellow for 2014. Ms. White researched the collections of Thomas Jefferson, the Edgehill Randolph family, and the Nicholas family while at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

It was jarring to read. “Dear Sir:” began the 1814 letter from P. Randolph (possibly Peyton Randolph, son of U.S. Attorney General Edmund Randolph, acting Virginia governor from 1811–1812, and cousin of Thomas Jefferson) written to Wilson Cary Nicholas, 19th governor of Virginia and Jefferson in-law:

“I beg leave to enquire of you what disposition you intend to make of William? If you do not wish to keep him, I am anxious to have him sold, in order to meet the note … which will shortly become due…I would thank you to employ some one to sell him immediately… Be so good as to let me hear from you on that subject.”

The polite exchange between the two white southern patricians left me feeling sick as I read about William, the enslaved man whose life meant little more to them than settling a financial obligation. I bristled while contemplating that both white men, public servants of a fledgling democracy, founded on the proclamation that “all men are created equal,” held in the balance a black man’s future, a man who would probably die a slave, as would his children, and grandchildren. My twenty-first-century mind couldn’t wrap itself around his nineteenth-century condition. Yet, I held in my hand this letter, a letter that’s part of the University of Virginia Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library’s rich archive about Jeffersonian history.

I spent long happy days at the Small Special Collections, poring over letters, official documents, old photos, even examining locks of Thomas Jefferson’s hair, in search of my own family’s ties to Jefferson and his extended family. Oral history, fragmented documentation, and DNA testing indicate that my African American family is directly descended from Thomas Jefferson and his wife Martha. Research points to my great-grandmother Rachael Robinson having several children with Jefferson’s great-great-grandson Moncure Robinson Taylor shortly after the Civil War. It’s a relationship that seems to have begun when the couple was young and appears to have lasted decades. Perhaps they bonded during and after the harrowing years of the war. Whatever the case, I have come to believe theirs was a love relationship, one that brought me to U.Va. to learn more about them and the times in which they lived.

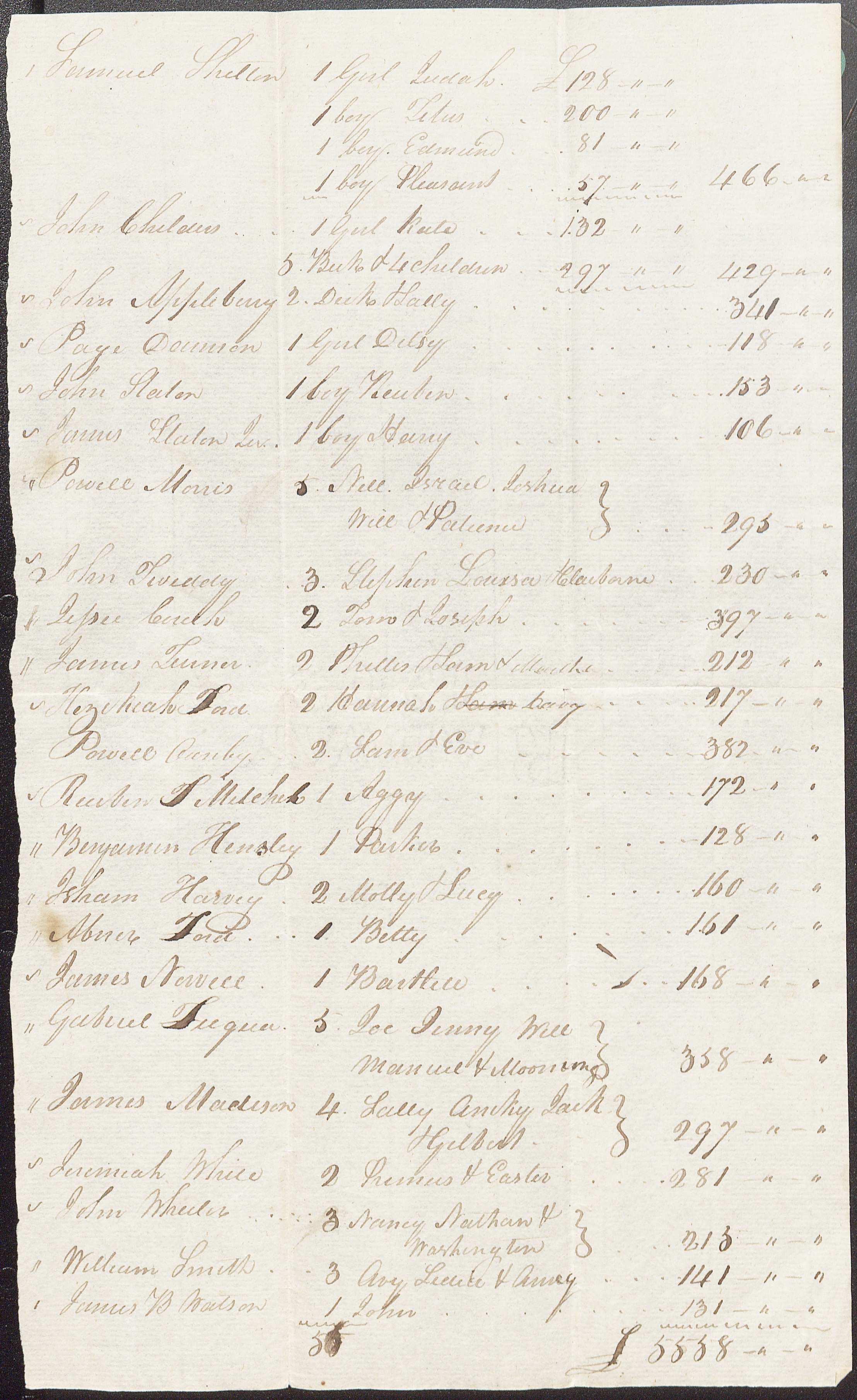

An Account of Slaves, n.d. (MSS 5533. Papers of the Randolph Family of Edgehill and Wilson Cary Nicholas. Gift of Misses Margaret and Olivia Taylor and Mrs. Mary Mann Moyer. Image by Petrina Jackson)

What I found was a record of lives interrupted and altered by disease, early deaths, war, and chattel slavery. And while I felt resentment and bitterness toward the people who owned William and others who wrote dismissively of their enslaved people, I also found myself captivated by and at times sympathetic to the tragedy of their lives. For example, Jane Hollins Nicholas Randolph, wife of Thomas Jefferson’s grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph and my great-great-great-grandmother, lost five of her 13 children.

Portrait of Jane Hollins Nicholas Randolph, n.d. (MSS 5533-c. Additional Papers of the Randolph Family of Edgehill on deposit from Steven M. Moyer. Image by Petrina Jackson)

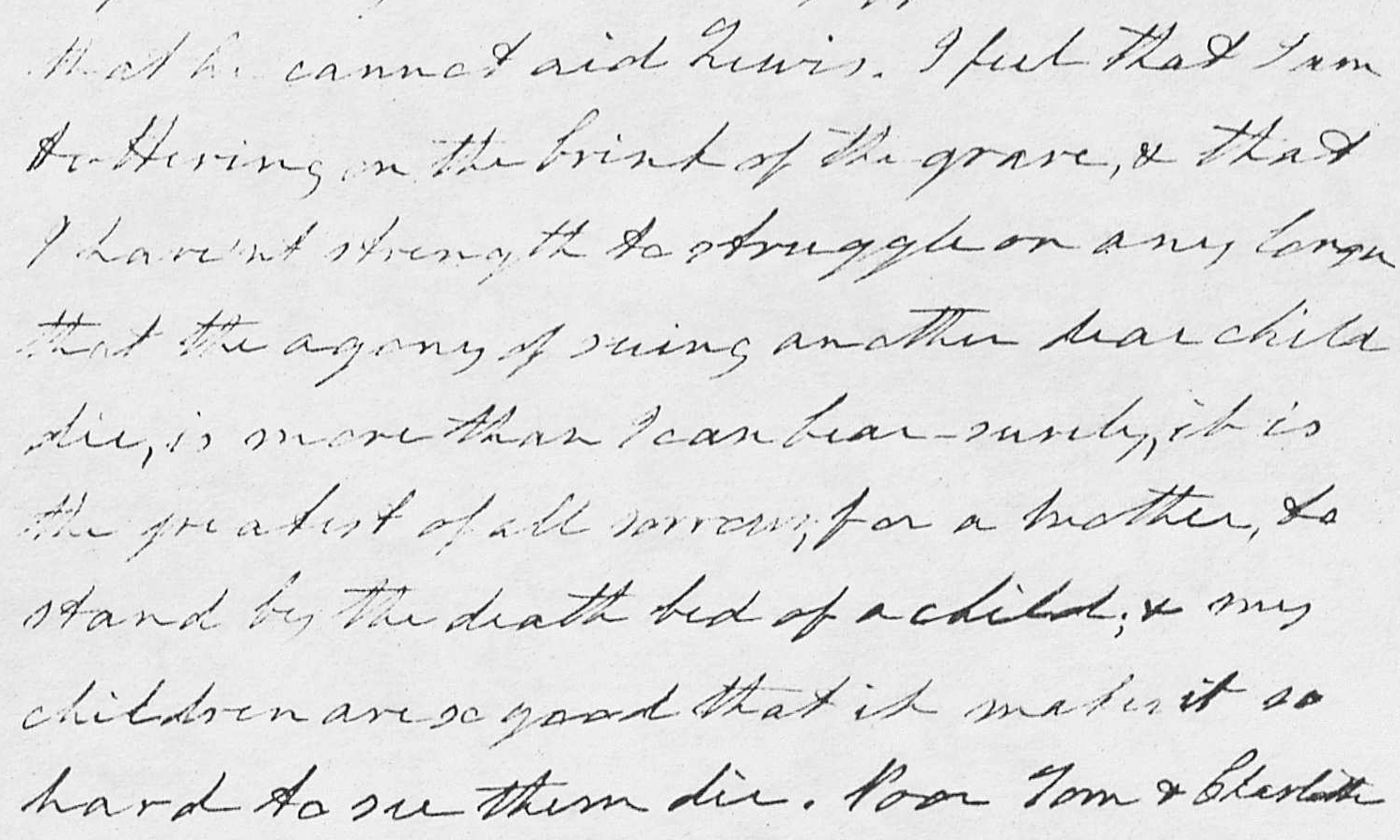

The Civil War shattered her life–she and her family were, after all, on the wrong side of history. Still, I couldn’t help but feel sympathy for her as I read the words of this November 15, 1870 letter from her to her cousin Mary:

“You have probably heard from others, dearest Mary of Lewis, I fear almost desperate state of health, caused by taking cold last December which he never got rid of which has brought him to a most alarming state…

I feel that I am teetering on the brink of the grave, & that I haven’t strength to struggle on any longer that the agony of seeing another dear child die is more than I can bear – it is the greatest of all sorrows for a mother… to stand by the death bed of a child & my children are so good that it makes it so hard to see them die.”

Detail of copy of letter from Jane Hollins Nicholas Randolph to her cousin Mary, 15 November 1870. (MSS 9828-a. Additional Papers of the Randolph-Nicholas Family. Image by Petrina Jackson)

Jane Randolph died two months later, struck down by the news that her youngest child Lewis, the one whose life-threatening illness had her “teetering” at the grave, would soon succumb to “consumption.” How could I not feel for her–I, too, am a mother.

Yet this woman, my ancestor, owned slaves, some of whom may have been my ancestors as well. Jane’s former enslaved people were said to have wept at her gravesite. I too wept as I read her plaintive letter, one of many she had written and that are housed at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. For me, Jane’s letters gave her a humanity that history had stolen. Poor William and other enslaved people will never have theirs restored.

Vintage Cameras, Modern Art, and U.Va.’s Secret Gardens: Eight Questions for Penny White

This week we introduce you to another of our wonderful new hires in Special Collections, Penny White, Reference Coordinator, who began her new position this summer. Penny is an Ohio native (Go Browns!) and received her B.A. in Art History from Wright State University in 2009. She came to librarianship after beginning a graduate program in Art Education and Museum Studies at the Ohio State University. Her interest in libraries and public service led her to change majors and transfer to Kent State University, where she received her M.L.I.S. in 2013. While at Kent State, she jumped at the chance to gain experience processing archival collections, working the reference desk, and curating an exhibit as a graduate student in the Special Collections and Archives department. She told us, “I am excited to continue sharing in the Special Collections experience with all of you here at U.Va.” We asked Penny to answer a few questions and she obliged with her customary warmth and humor.

What was your first ever job with books or libraries?

My first ever job with books was as a page in my local public library during high school. I worked in the children’s department, which was tremendous fun!

What was the first thing you collected as a child? What do you collect now? (oh, c’mon, admit it).

I remember having a stamp collection when I was younger, but I don’t believe I was an avid stamp collector. What does stand out from those early years is a memory of my sister Corey and I collecting tiny toys–though now it seems more like hoarding. We had at least two huge tins full of everything from trolls and My Little Pony, to Happy Meal toys and Matchbox race cars.

Now I collect vintage cameras. I did a series of prints using images of Kodak Brownie Junior and Hawkeye cameras, among others, for my screen-printing final project senior year of undergrad. After that, I was hooked. I love the way they look, like art pieces themselves. The evolution of design and technology over time is fascinating.

Hopefully you’ve been roaming Grounds and Charlottesville a bit since your arrival. What’s your favorite new discovery other than Special Collections?

I really love all of the outdoor seating and green space that Central Grounds has to offer. The gardens behind the Pavilions are an excellent place to eat lunch; they have a very serene atmosphere. When I first saw them, they reminded me of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden.

Name something about Special Collections or U.Va. that is different from what you expected.

I think it can be very nerve-wracking coming to a new place because you do not know what to expect. Your opinions have yet to be formed–how well will you do? what ill the people will be like?–but that is half the fun.

The depth of history here is much more prominent than where I came from. The lingo, too, was unexpected. I was hard pressed at first trying not to use “campus” and “freshman” when referencing the grounds and first-years. But while there have been differences, there have also been a great number of similarities. The University’s drive to share in the learning process is a familiar one as is the great emphasis Special Collections puts on public service.

If you could be locked in any library or museum for a weekend, with the freedom to roam, enjoy, and study to your heart’s content, which one would you choose?

The Tate Modern, hands down! London is probably my favorite city and the Tate Modern inspired my interest in exploring the relationship between museum and community. When the museum was being constructed, the project managers got the community involved with the planning and construction of the building as well as events and programs. All of this contributed to the ongoing Southwark Regeneration program.

Besides, the collections and installations would take weeks to see and fully appreciate!

When you came to interview, we showed you the miniature book collection. If you can remember, tell us what you thought to yourself when you found out we had 14,000 miniature books.

To be honest, my mind was still wrapping itself around the size of the stacks and the sheer size and variety of the overall collection. It wasn’t until I met a patron working with miniatures that I really found them to be amazing. She very excitedly displayed a tiny book, the size of a button. It was much smaller than I would have expected but full of intricate detail. After that, I found myself in awe of the craftsmanship involved in turning out beautiful works in such tiny frames.

Tell us your go-to Thomas Jefferson quote (if you don’t have one, get one. You’ll need it!).

What really drew me to this position was the fact for Jefferson, learning was a lifelong and shared process. This thought is so befitting a library– what is a library without books?:

“Some of the most agreeable moments of my life have been spent in reading works of imagination.”

Our collections happen to be filled to the brim with history and imagination.

You’ve chosen to work in Public Services, so clearly you like to communicate! Pick one form of communication:

Tumblr

Texting

Landline

U.S.P.S.

carrier pigeon

other: _____________

Explain your choice:

I have been fortunate to meet people from all over the world through my studies and Facebook allows me to keep in contact with them regularly: following travels, planning get-togethers, sharing photos, and catching up. Facebook has also been a wonderful platform for information sharing, networking with other professionals, and staying abreast of new developments in my areas of interest.

As you can imagine, we are thrilled to have such a culture vulture joining our staff! Be sure to say hi to Penny next time you’re in the reading room. And stay posted–we’ll be back with a third new-staff welcome post in a few weeks.