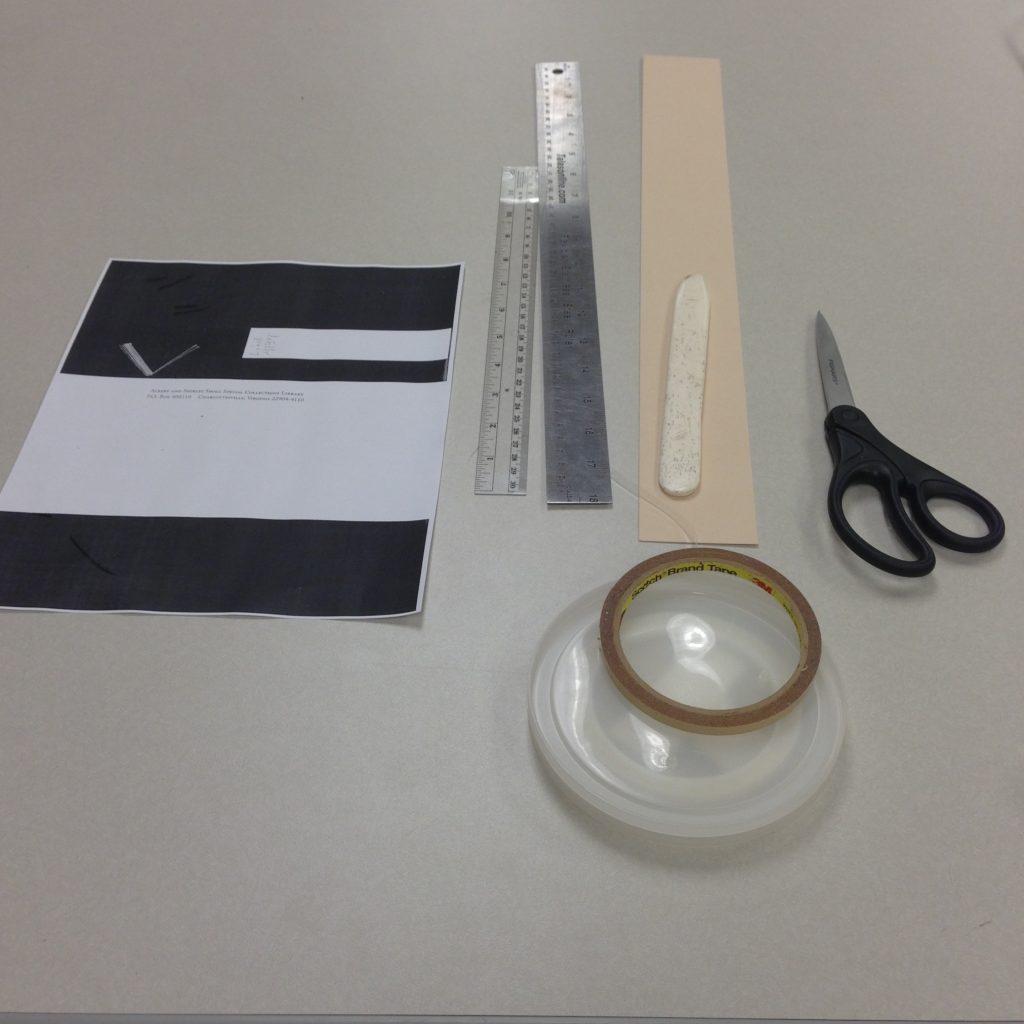

This week Nicole Bouché, Director of Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, relates the story of how a major new acquisition came to U.Va.:

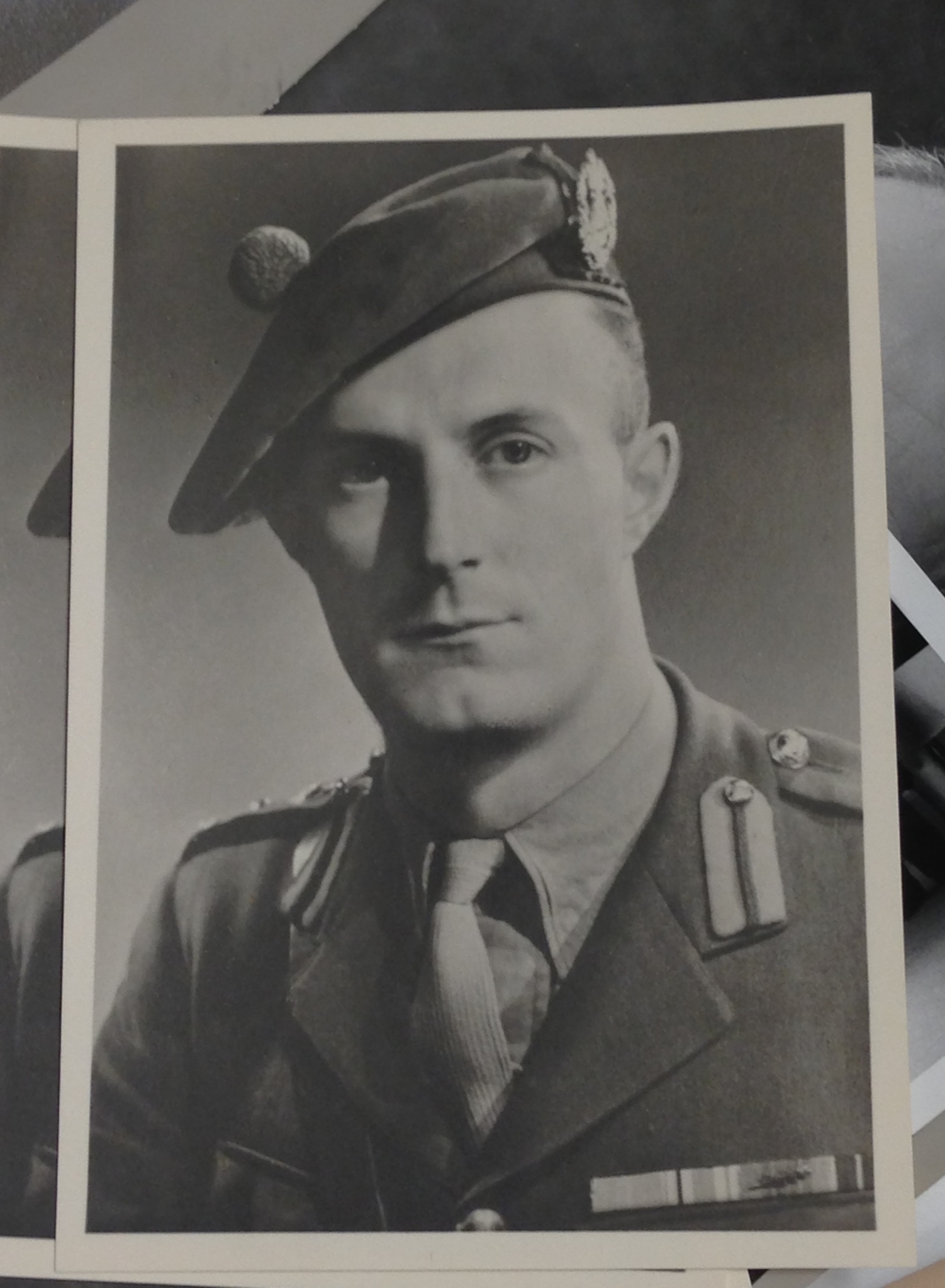

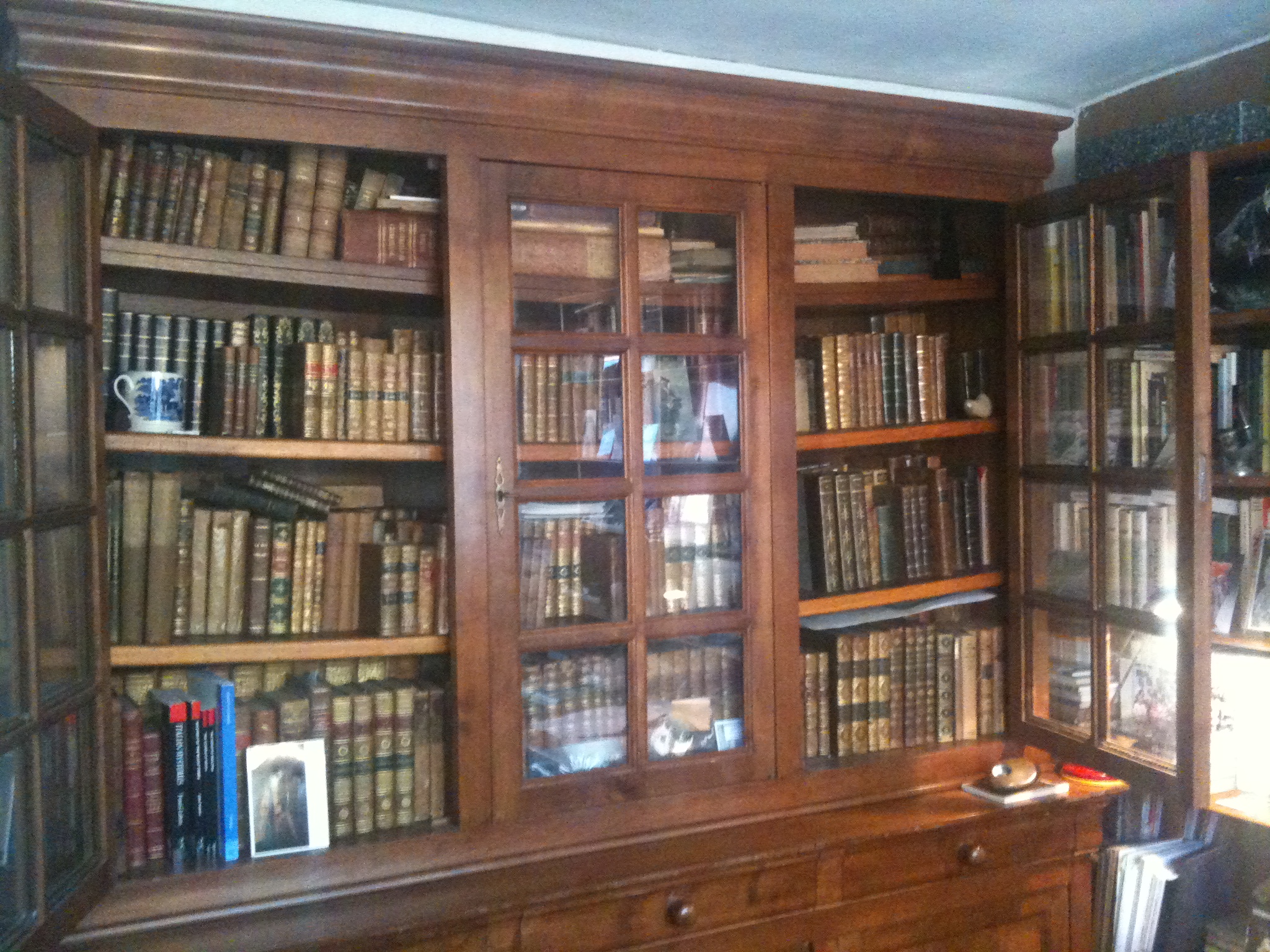

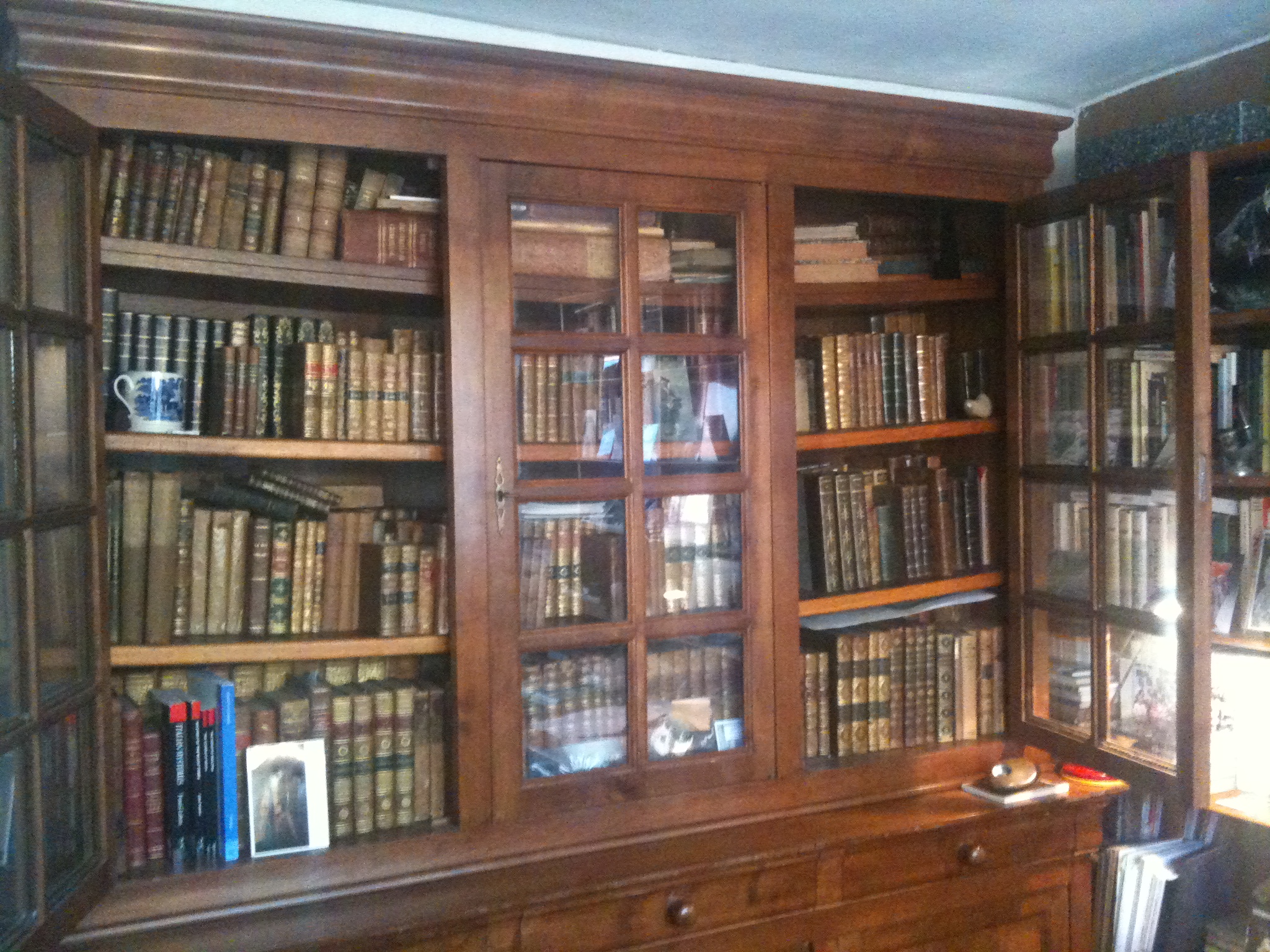

Maurice Lévy in his Toulouse study, seated before the glass-front bookcase containing his French Gothic collection.

“I have now reached a time in life where one inevitably ponders over the fate of the books one may have had the good fortune to collect over the years.” —Maurice Lévy

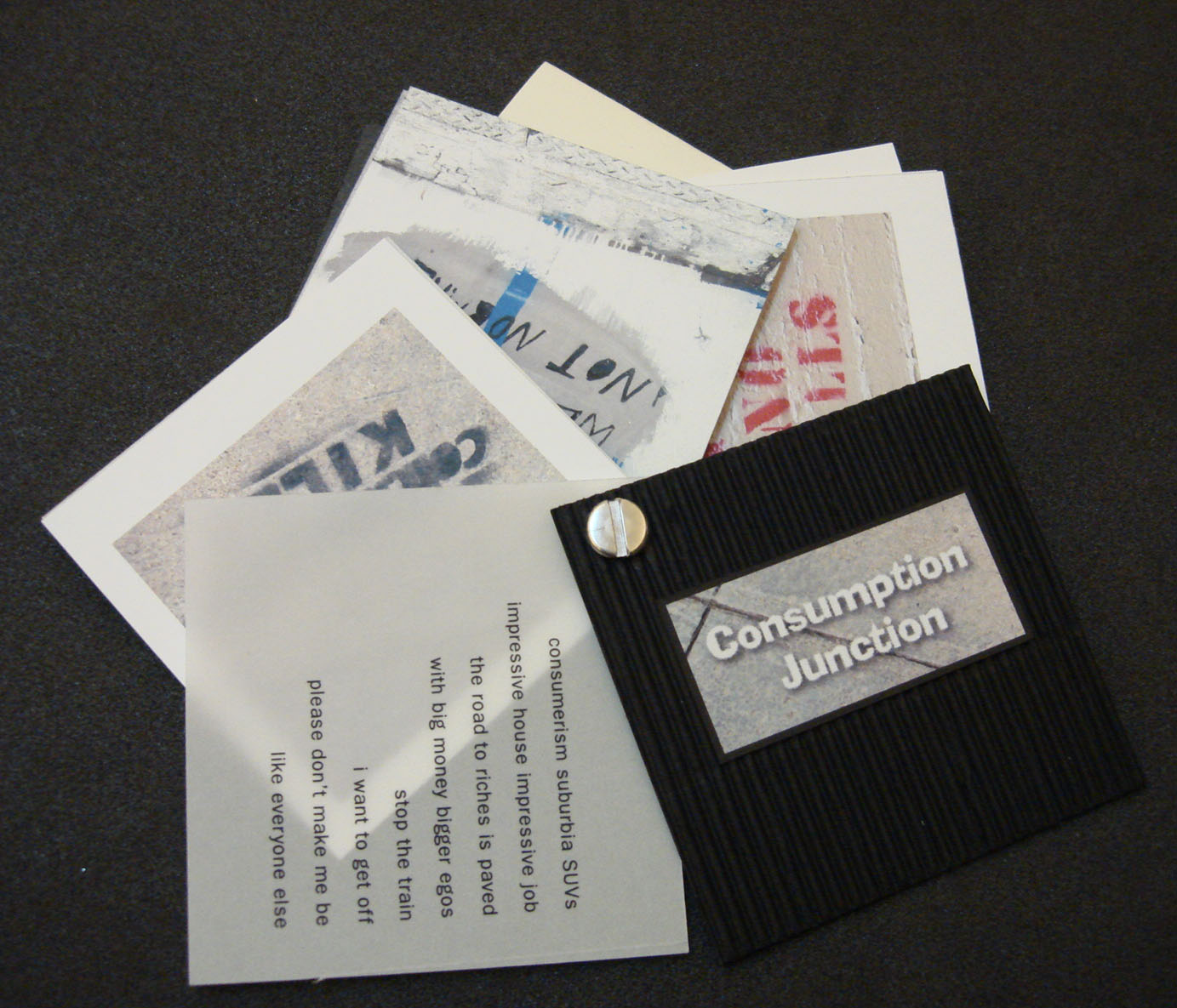

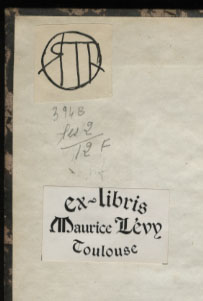

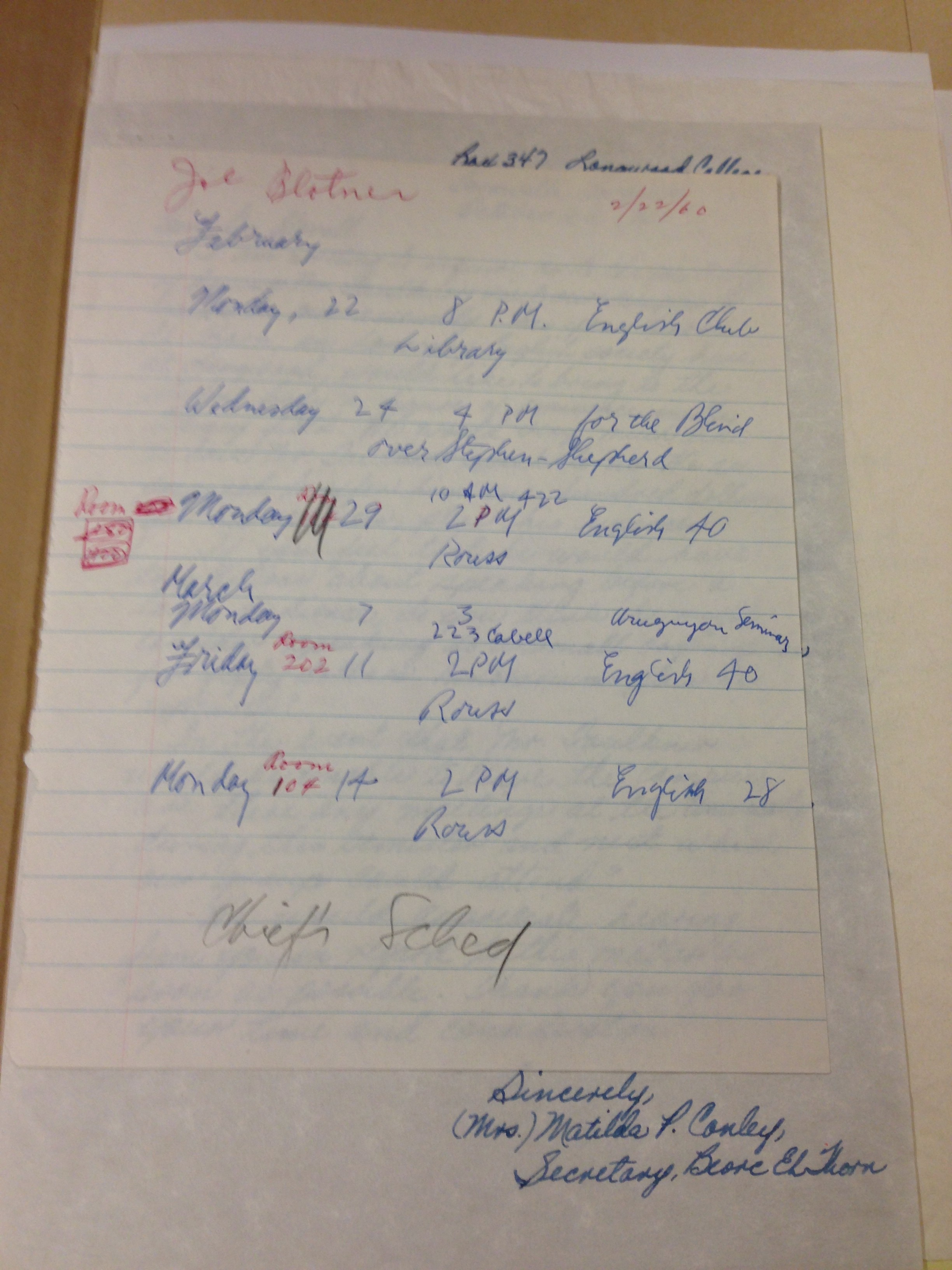

Serendipity often plays a role in building great library collections, and a chance encounter between an institution and a scholar can yield an extraordinary and wholly unanticipated legacy years, sometimes decades, later. Such is the story of the Maurice Lévy Collection of French Gothic, a recent bequest of over 450 rare books now housed in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

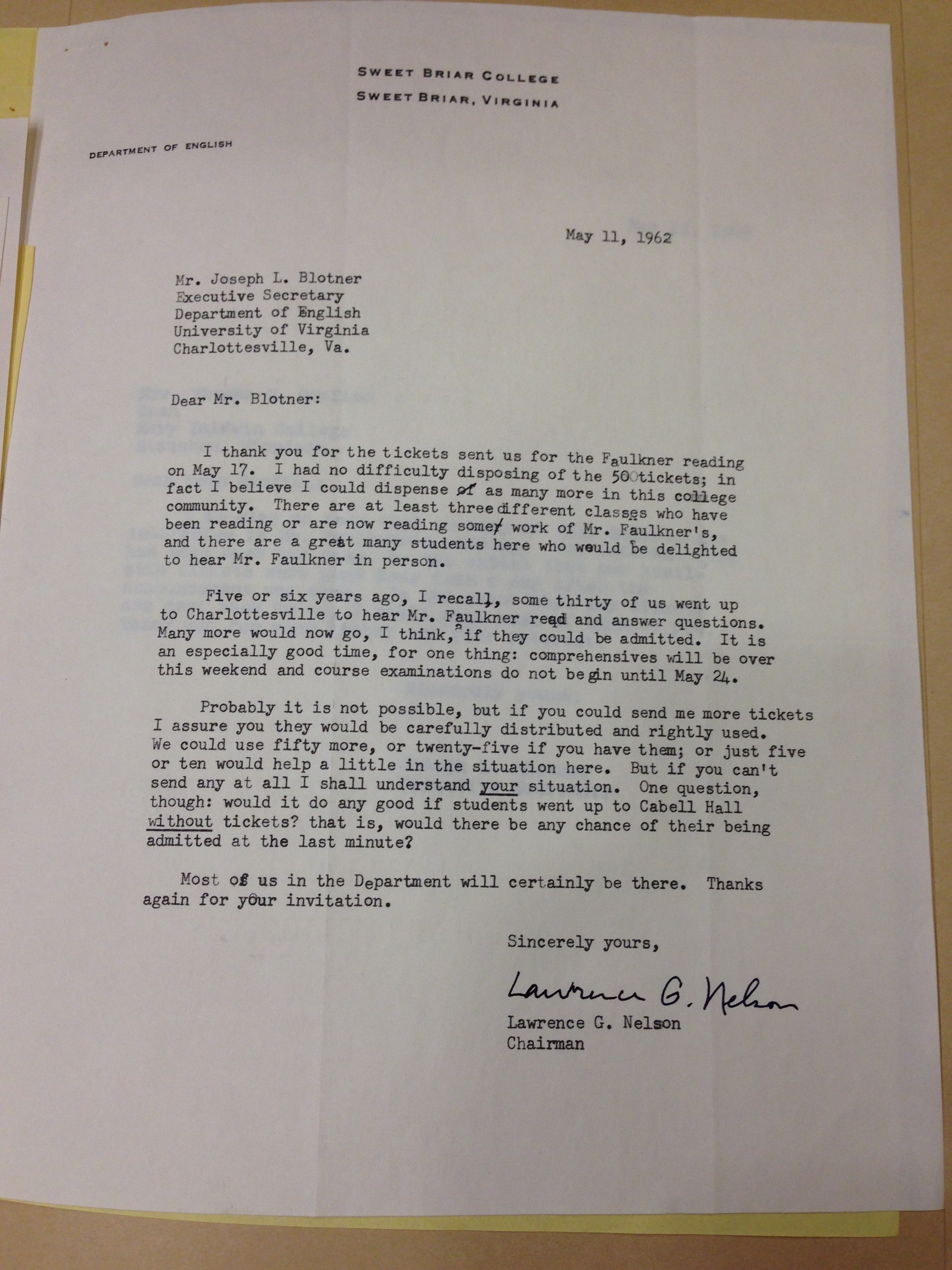

Sometime in the early 1960s, Maurice Lévy (1929-2012), then a graduate student of English Literature at the Sorbonne in Paris, proposed to write his dissertation on the American writer, William Faulkner. “Ah, but we don’t write dissertations on living authors” was the (predictable) reply from the French academy.

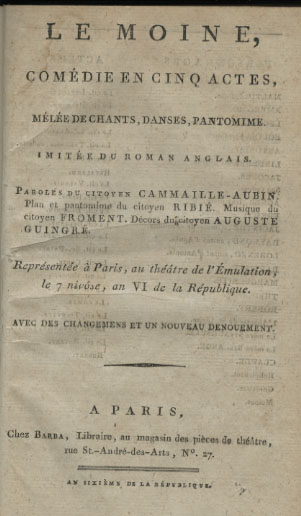

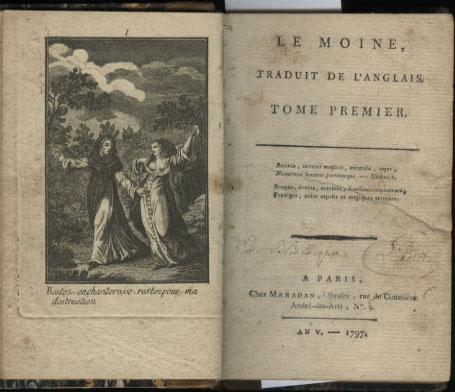

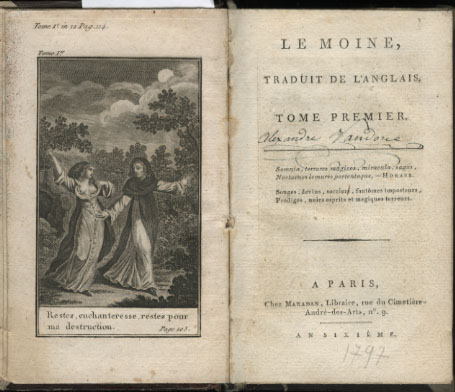

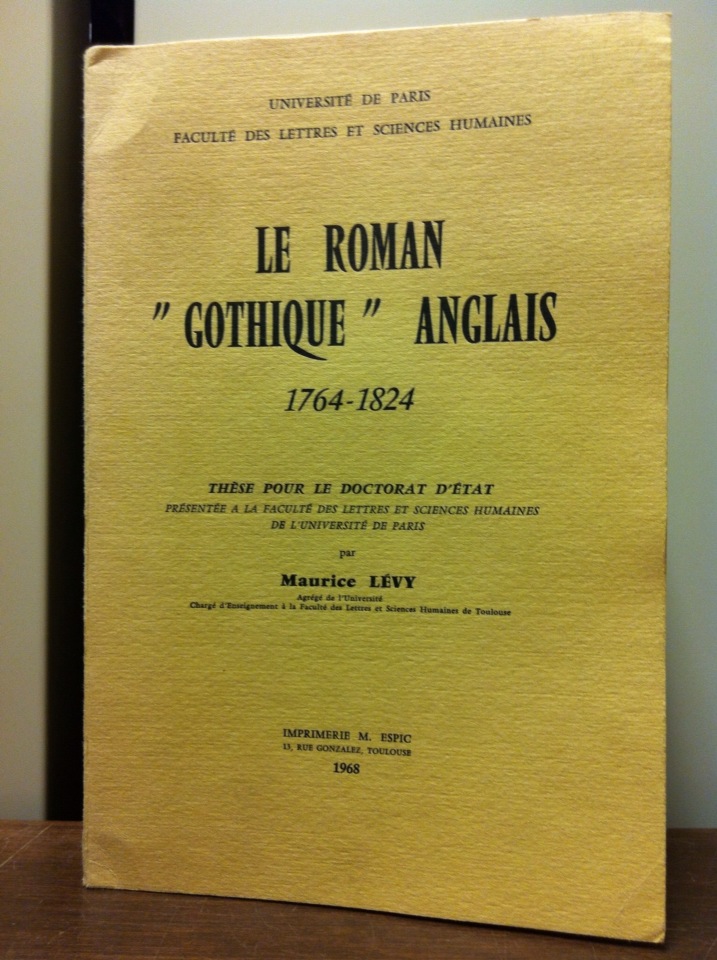

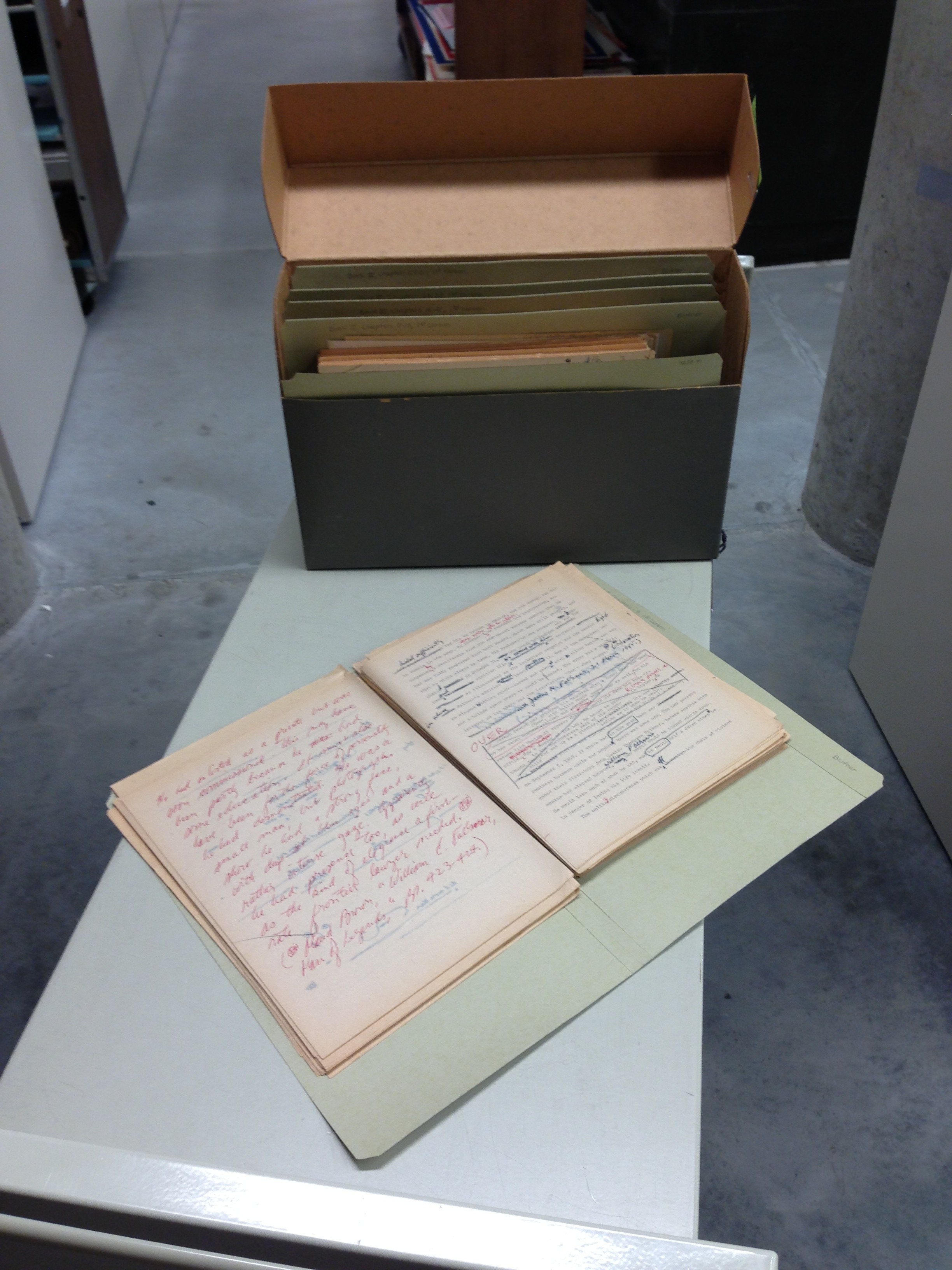

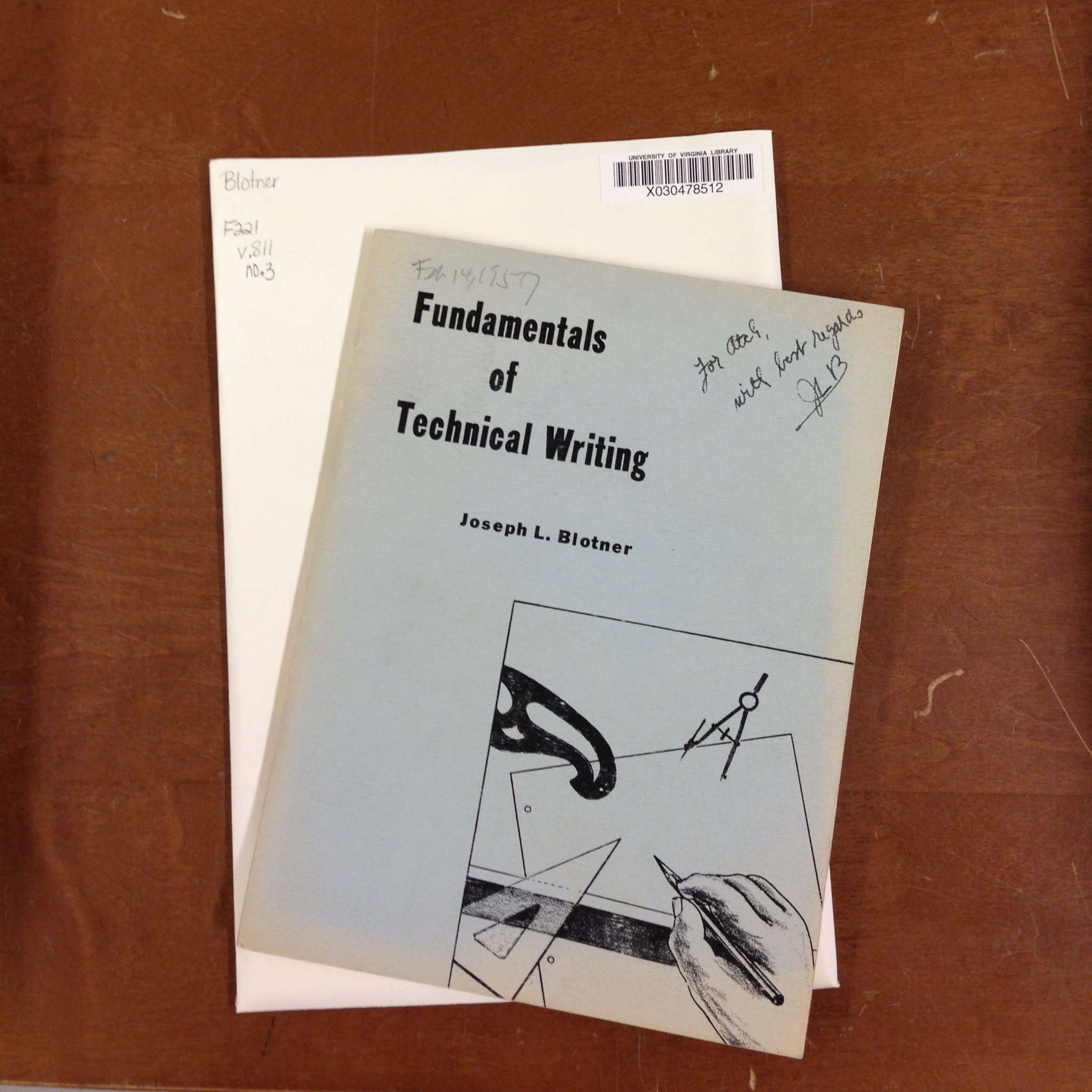

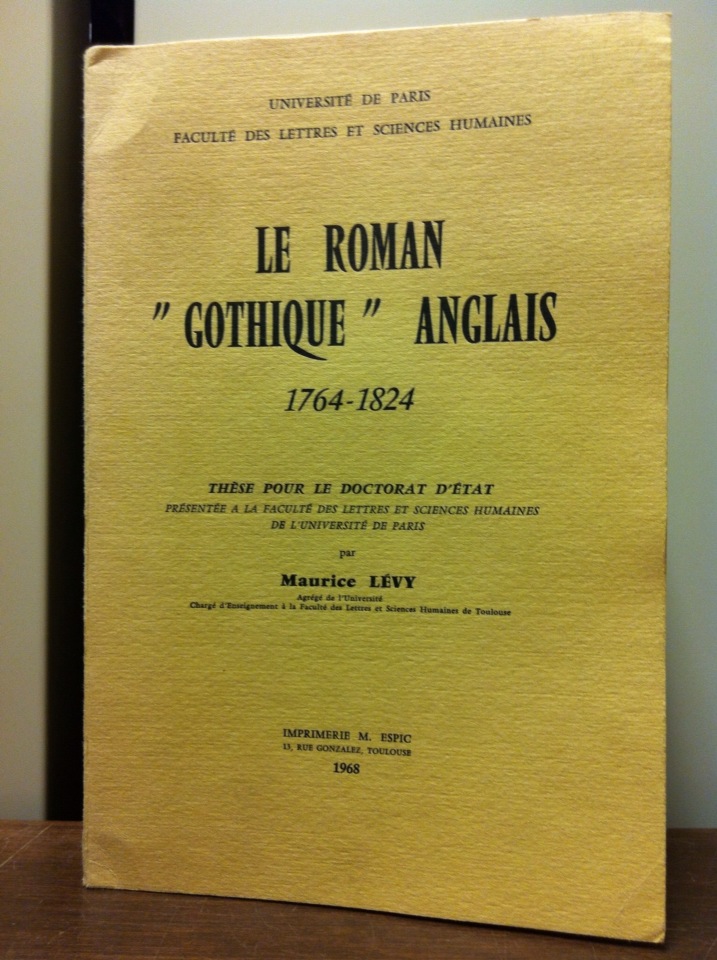

Instead, the young scholar was assigned to write about English gothic literature. With the help of a summer fellowship Lévy found his way to U.Va., where he spent three months immersed in an intensive study of the Sadleir-Black Collection of Gothic Fiction, among the world’s finest collections on the gothic genre. Lévy’s dissertation, Le Roman “Gothique” Anglais, 1764-1824, became a standard source and helped to revive scholarly interest in the field, and Lévy became a recognized authority on the gothic genre. Maurice’s final work, a scholarly edition of Matthew Gregory Lewis’ classic gothic tale, The Monk, was published posthumously in 2012.

Maurice Lévy’s doctoral dissertation, based in part on research done with U.Va.’s Sadleir-Black Collection of Gothic Fiction.

At the end of his fellowship, Lévy returned to France, never to return to Charlottesville, but with fond memories of his summer on Grounds. By his own account, he was never again in contact with the U.Va. Library, or with the Rare Book Department staff that had been so welcoming and helpful during his stay.

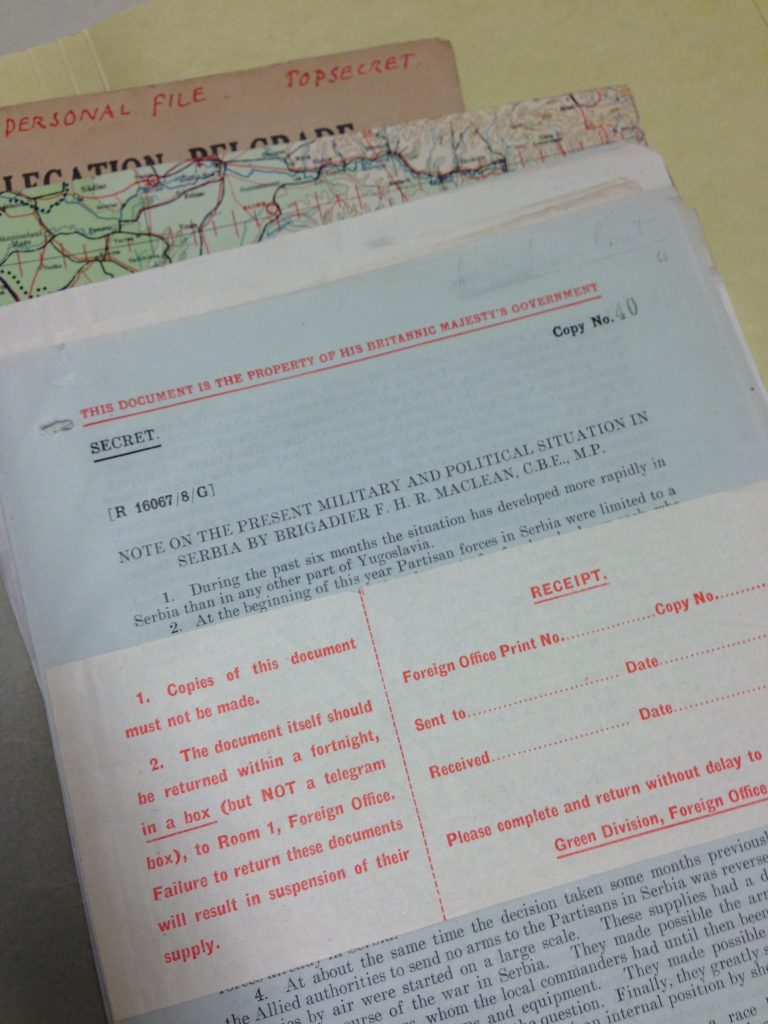

Jump forward several decades: Lévy, now an emeritus professor of the Université de Toulouse, “pondered” what do with the treasured collection of French editions of gothic novels that he had painstakingly assembled. An American colleague recalled how Maurice frequently spoke with deep appreciation of his summer spent in Charlottesville. Might U.Va. be a possibility? And thus, in the fall of 2009, an e-mail arrived in Special Collections from an “unknown” French scholar, inquiring whether the library might perhaps be interested in acquiring his collection.

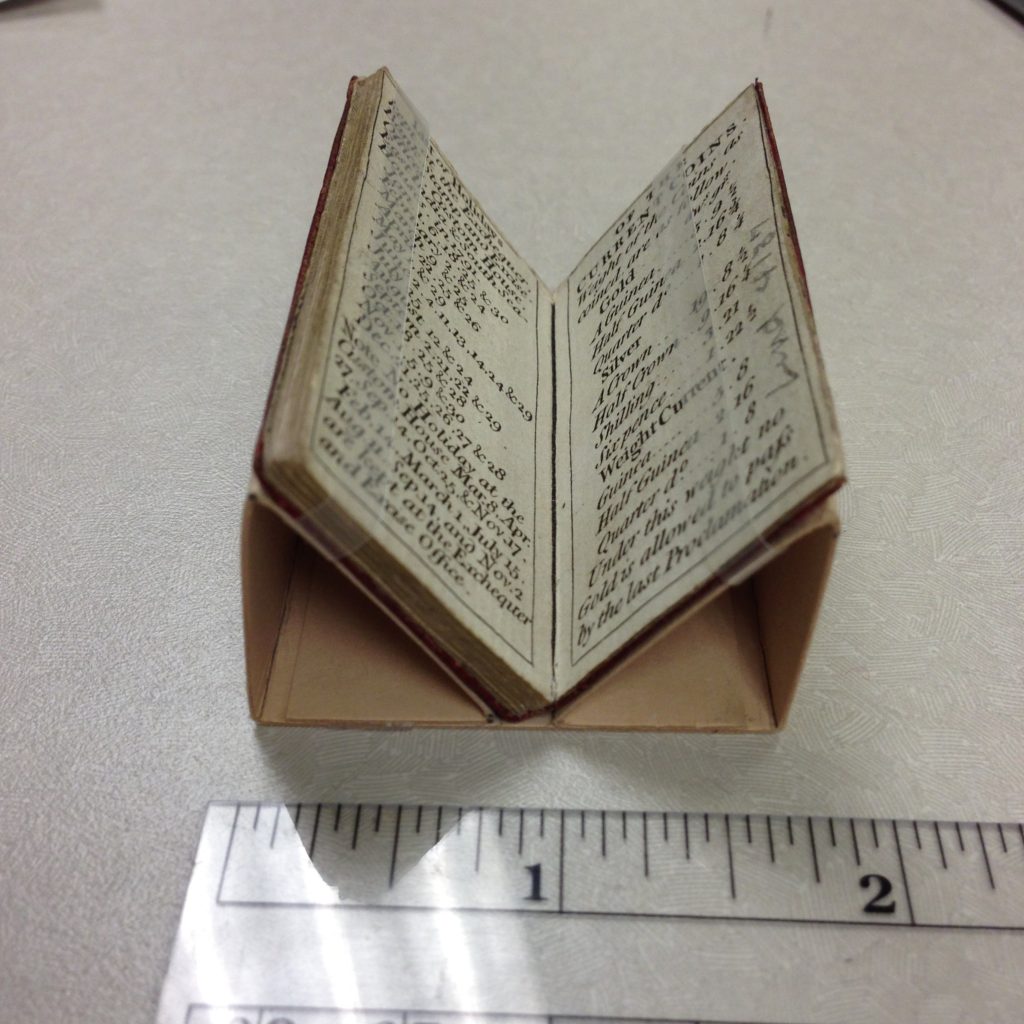

… most of them first or early editions: about 60 titles, representing something like 200-250 volumes …. which compose, literally speaking, the French side of the same literary movement and could perhaps be considered by future researchers as a helpful complement, however modest and limited in size, of the prestigious Sadleir-Black collection.

I am currently looking for a home for this collection, which, although relatively modest in size when compared to others, has the advantage of illustrating the extraordinary vogue of the “roman noir” during the French Revolutionary period, and of including volumes which offer the distinctive feature (not shared by corresponding English volumes) of being individually illustrated with frontispieces by (most of them) reputed engravers. To pay homage to their talent, I published Images de Roman Noir in 1973 [Paris, Losfeld].

Should you be interested in this donation, I would take the necessary legal steps to ensure that they eventually come into your possession after my demise, so that they may be made available to future students.

If, on the occasion of a visit to France, you wished to inspect the books, you would be very welcome to do so.

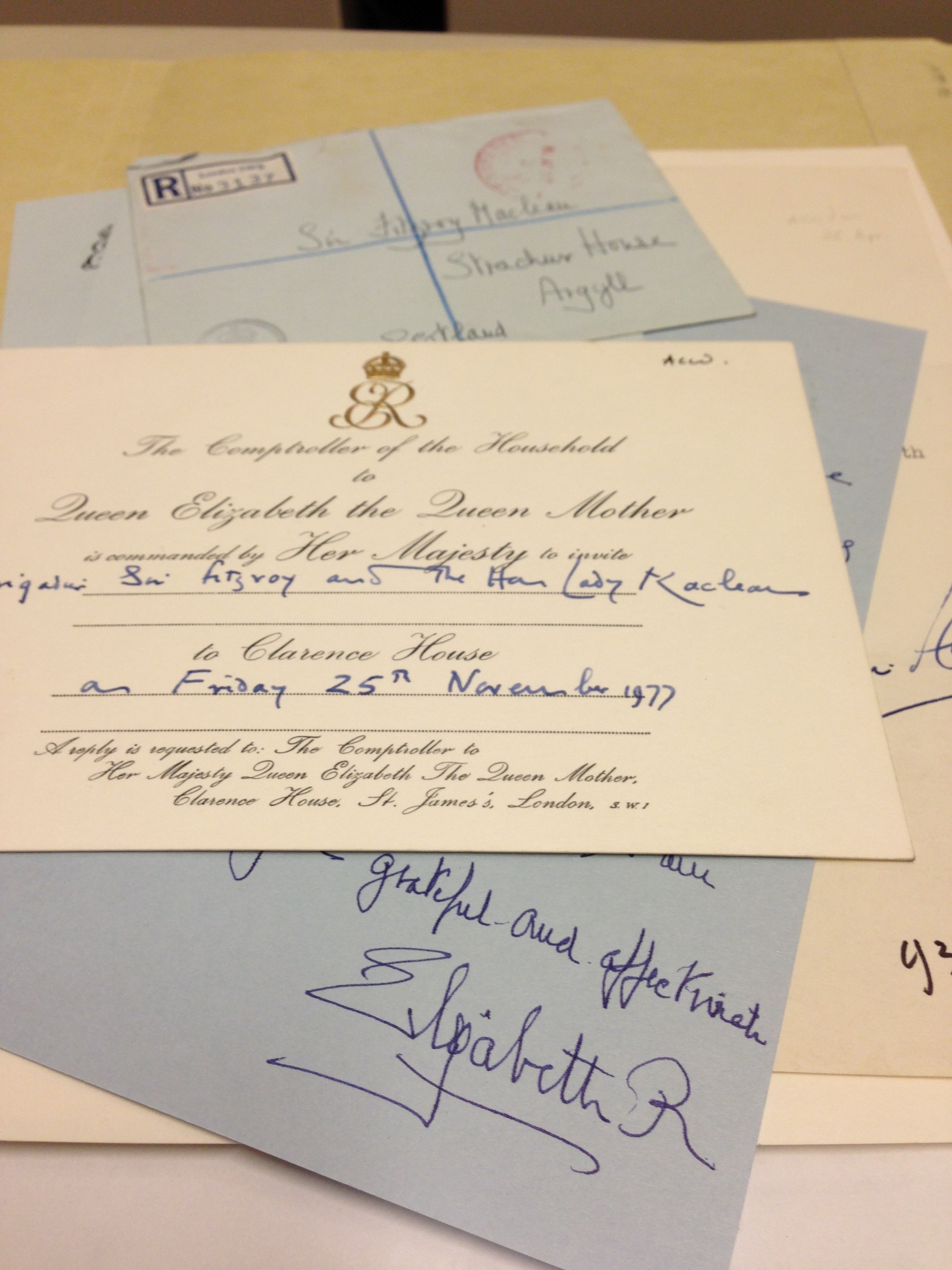

Lévy’s letter included a detailed title list. We were instantly intrigued, and our interest was quickly echoed by members of the English and French faculty. Whatever the likely costs (not to mention bureaucratic hassles) associated with shipping a large antiquarian book collection from overseas, this offer clearly merited serious consideration. A site visit was definitely in order. Happily, I had already planned a visit to France; a detour to spend a few days in Toulouse with Professor Lévy and his wife, Ellen (an American) was easily added to the schedule. Professor Lévy would meet me at the train station in Toulouse, where I would recognize him by the sign (“GOTHIC”) that he would be carrying.

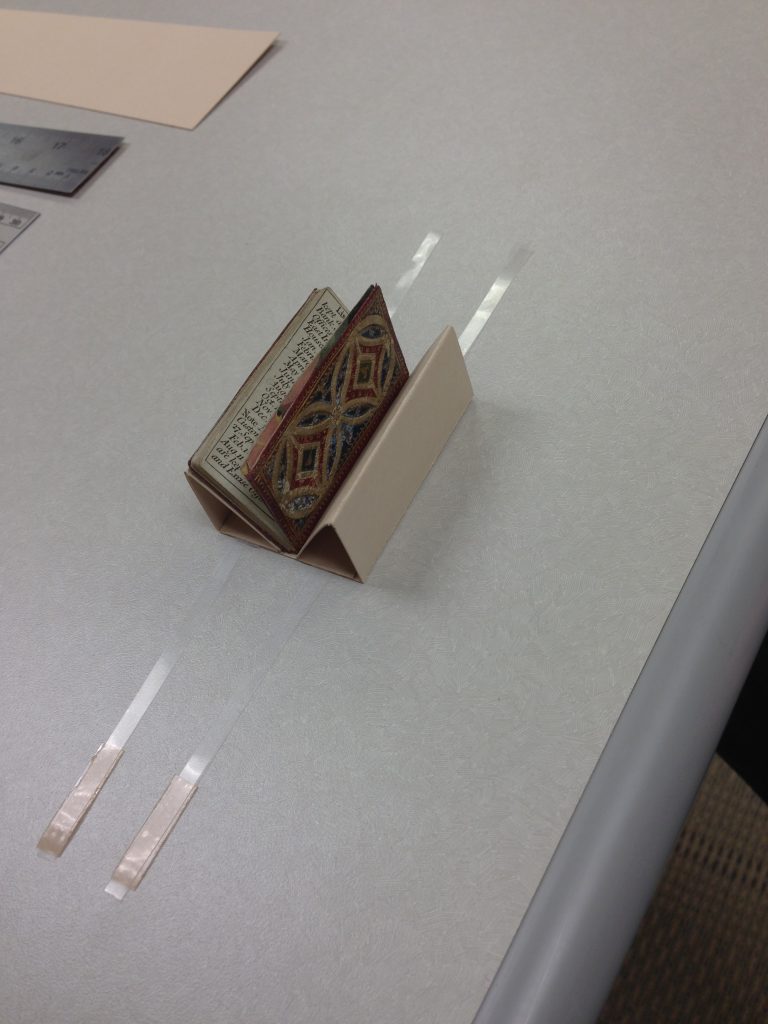

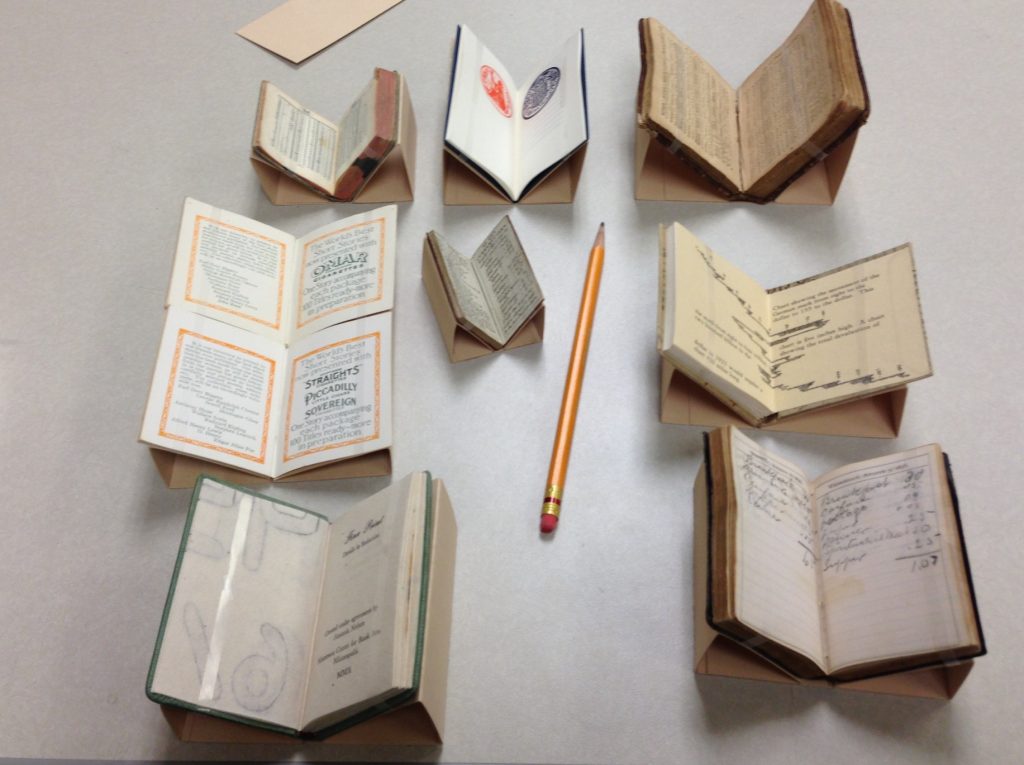

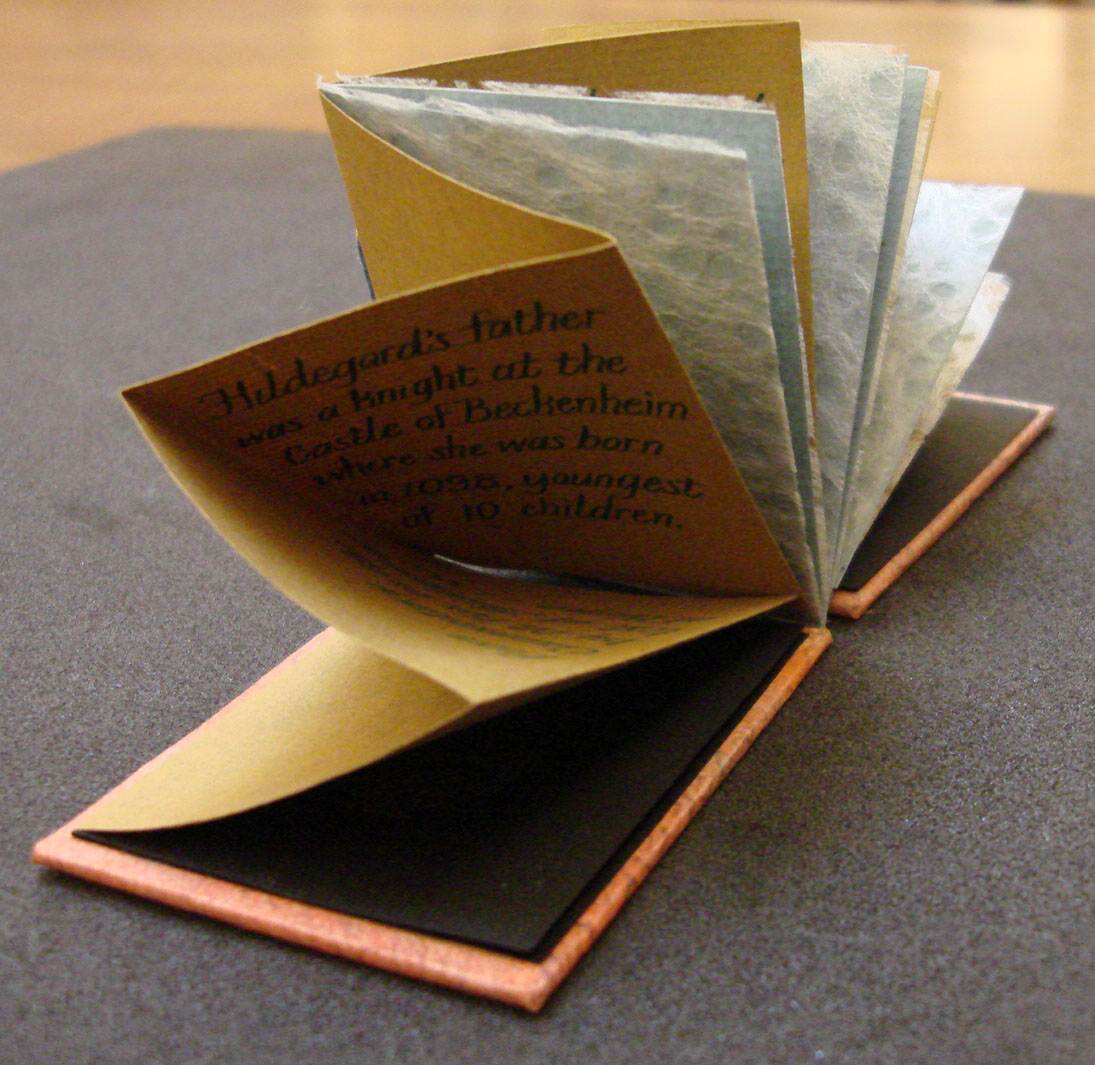

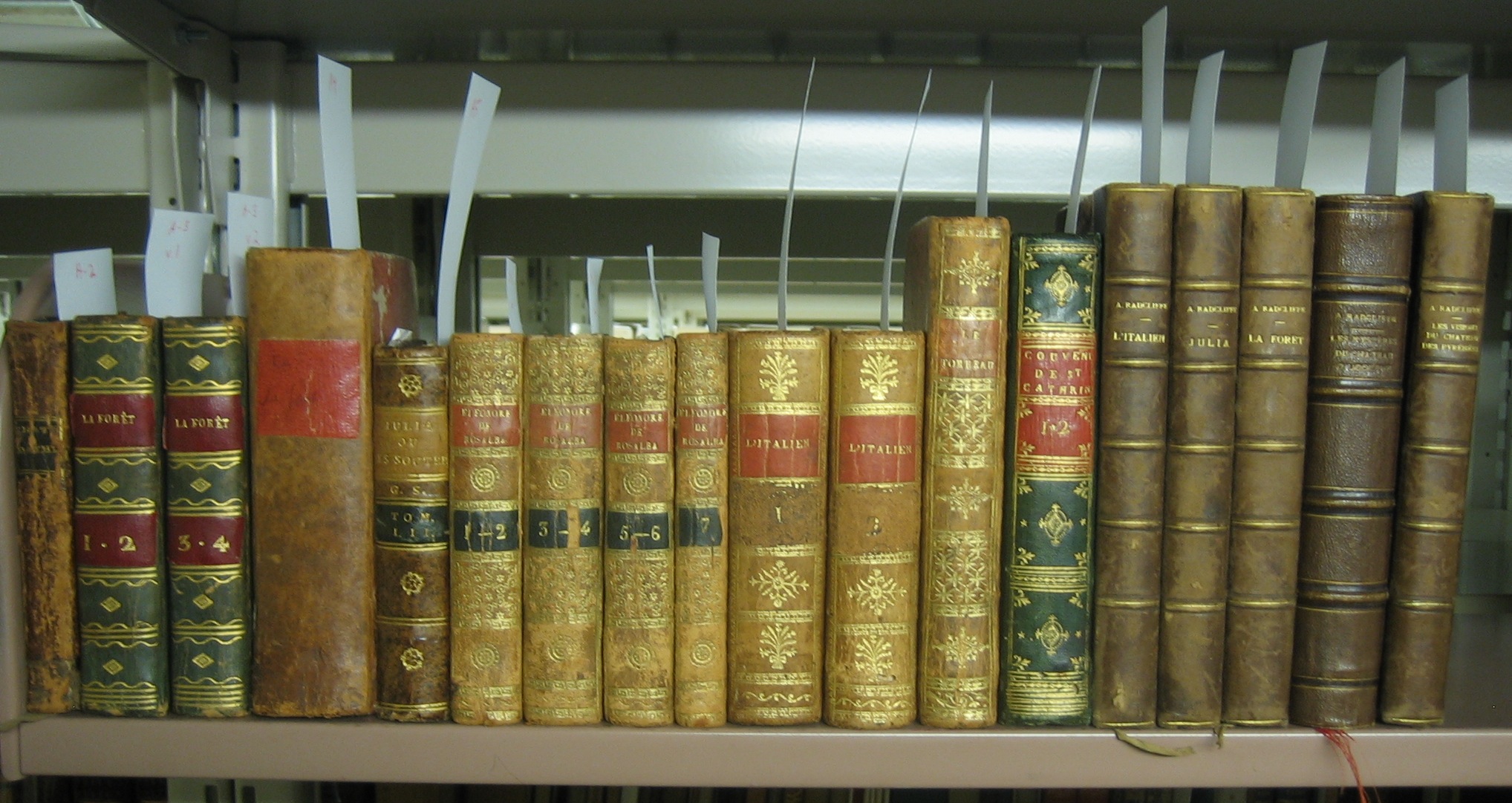

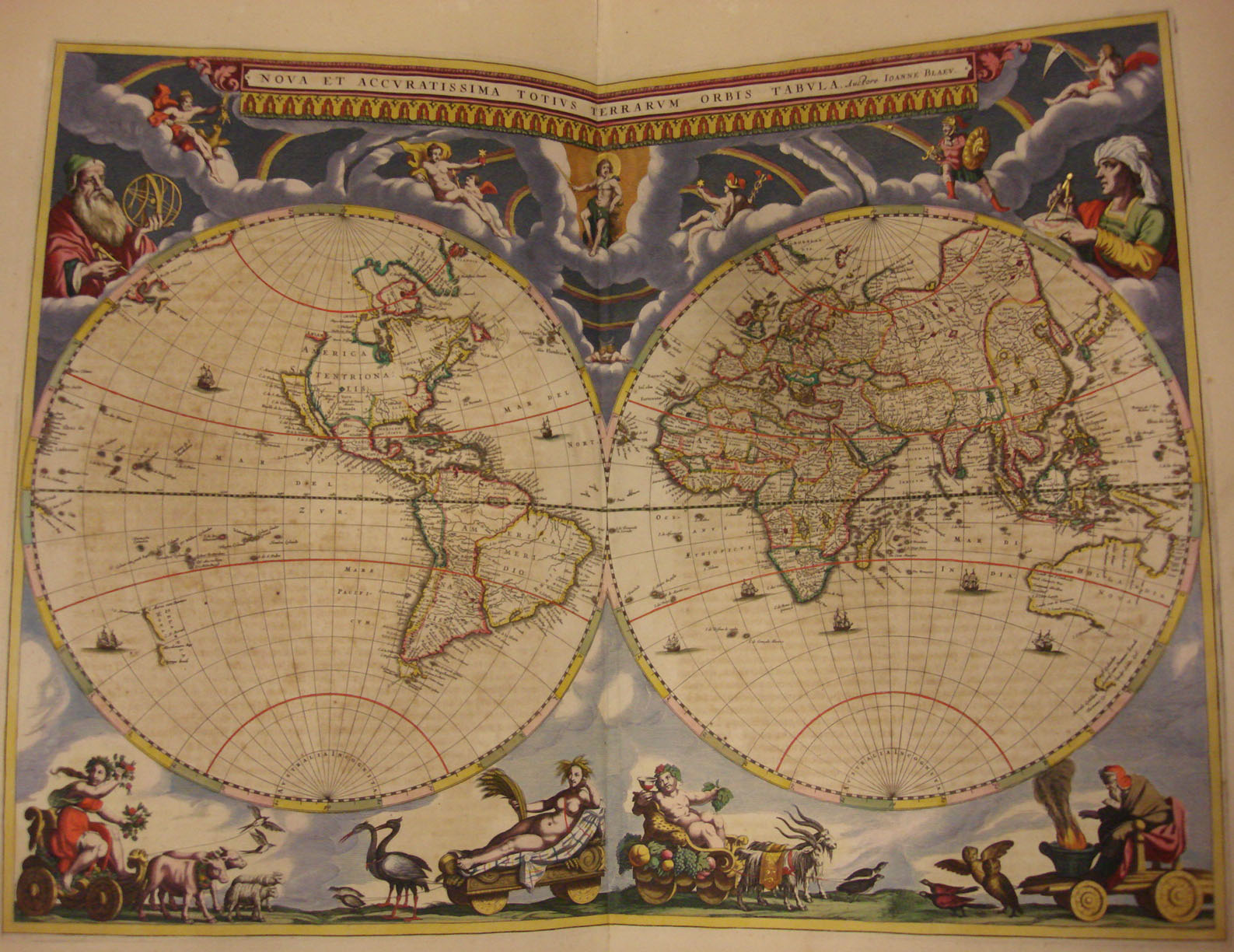

As we conversed on our first evening together at the Lévy home, warm memories of Charlottesville, surrounded by the riches of the Sadleir-Black Collection and the gracious hospitality of then Rare Book Librarian John Cook Wyllie and his colleagues, were still vivid in Maurice’s mind. It took very little time to confirm our interest in accepting the Lévy collection. And so we spent two enjoyable days reviewing and inventorying a seemingly endless stream of compact little volumes from the late 18th and early 19th century, almost all in their original, often quite striking French bindings.

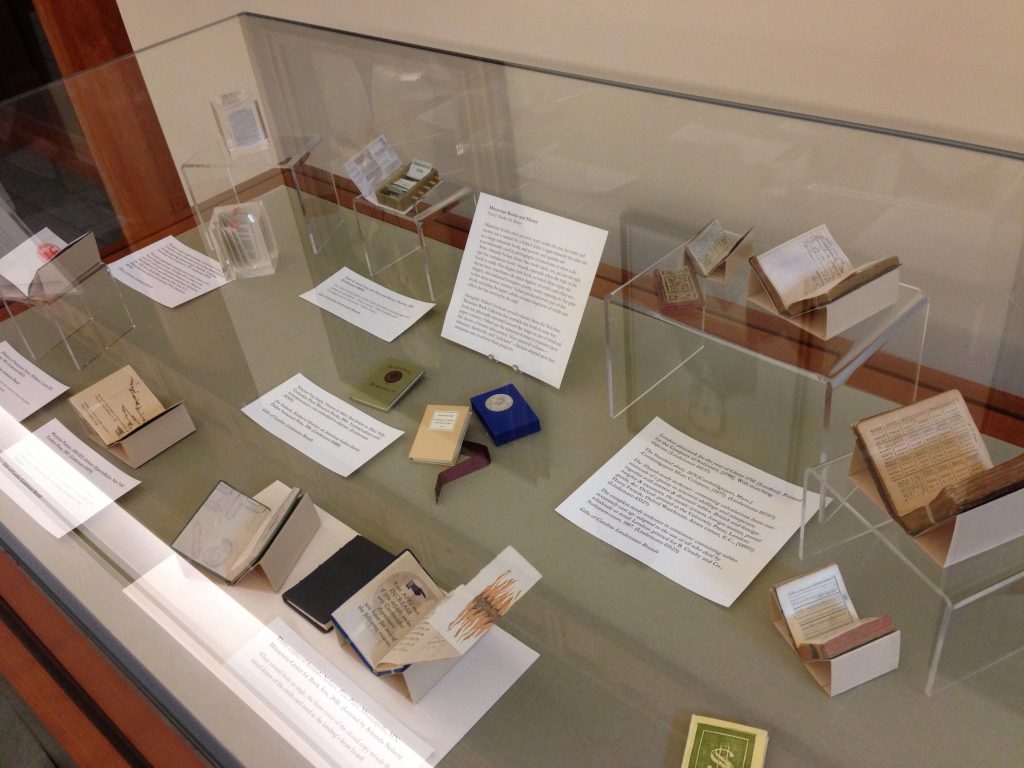

“Oh, the horror!” groan the sagging shelves of Maurice Lévy’s bookcase.

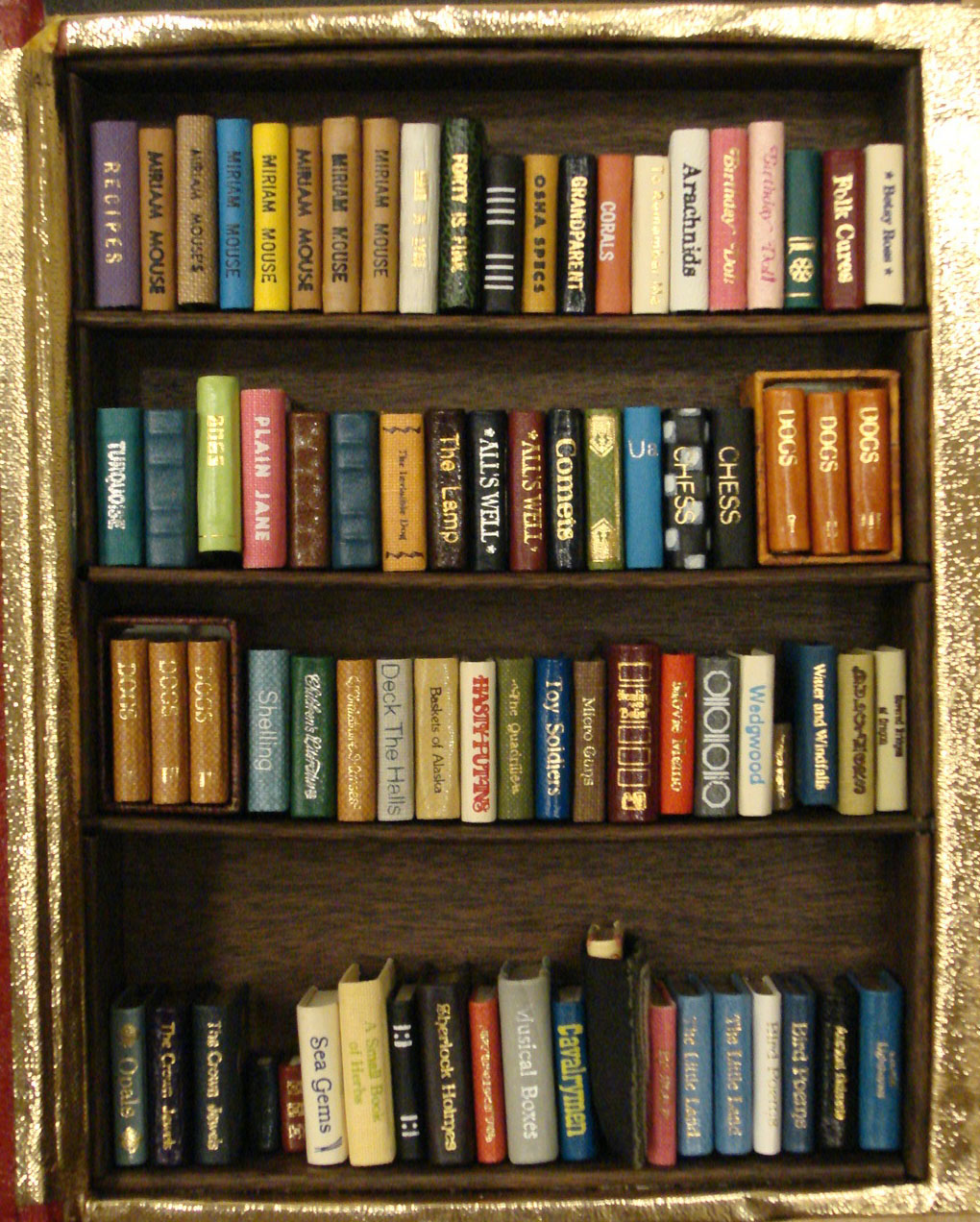

The large, glass fronted, wooden book cabinet in which they were stored occupied an entire wall of his study. It was tightly packed two, sometimes three, rows deep, and its thick wooden shelves were so full that they bowed at the center, giving the impression that the entire bookcase was weighed down by the burden of keeping these precious volumes safe from harm.

Maurice removed each work as though he were encountering an old friend. He would pause for a moment to recall the circumstances of their first acquaintance: when, from whom, and where had he acquired the title? What drew them together, and what special significance justified the volume’s retention and inclusion in the “special” bookcase? After a moment’s quiet reflection, Maurice would “introduce” the book to me, and we would add it to our growing list of titles destined for Virginia.

As our work progressed, it became clear that Maurice’s collection of French gothic accounted for only a small portion of the overtaxed bookcase’s contents. The remaining titles, he explained, were not his “French gothic collection” and would no doubt eventually find a home in France. There was neither time (nor encouragement) to explore these volumes: Maurice, after all, was still consulting his library for ongoing research.

I devoted a return visit in 2011 to assessing Maurice’s extensive reference library on the gothic. No further reference was made to the other, intriguing “old” volumes, which remained undisturbed in the bookcase. However, Maurice had decided that it was nearly time to see the French gothics safely installed at U.Va. We therefore said our good-byes with the understanding that I would return the following summer to oversee packing and shipment. Tragically, Maurice did not live to see the final transfer of his collection to U.Va. He succumbed to a long illness only weeks before my return to Toulouse in the summer of 2012. It remained for his widow, Ellen, his children, and the U.Va. Library to follow through on the terms of Maurice’s bequest.

But there was a new twist. Shortly before his death, as Maurice still had not arranged for the disposition of the remaining rare books in the old bookcase, his wife Ellen asked him about them. What should she do with them? “Offer them first to Virginia,” was his reply. And so she did. It was an interesting prospect, but just what books were they? Ellen could tell me little, occupied as she was with other family and personal matters. And so I arrived in Toulouse late last July to arrange for the final packing and shipment of the ca. 250 volumes in the Lévy French gothic collection, and to ascertain which, if any, of the remaining books might be of interest to the U.Va. Library.

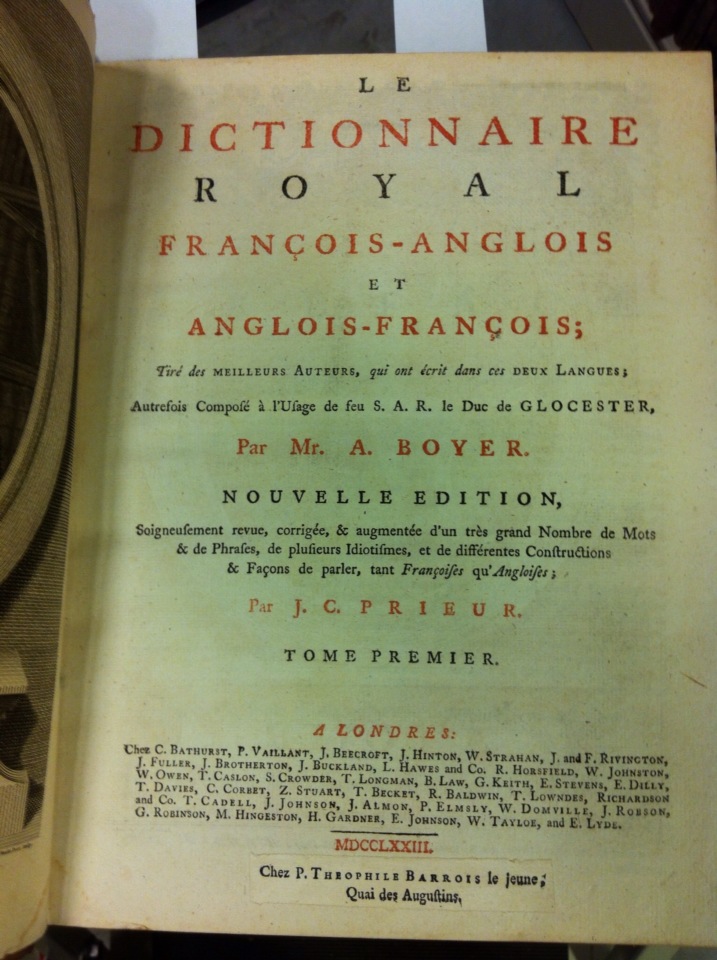

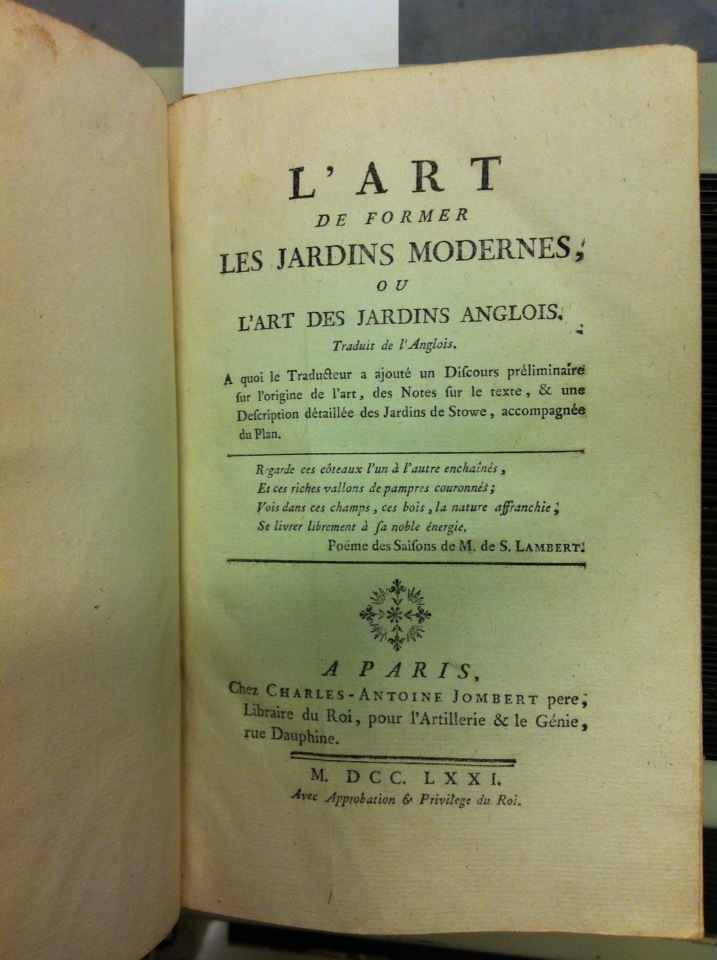

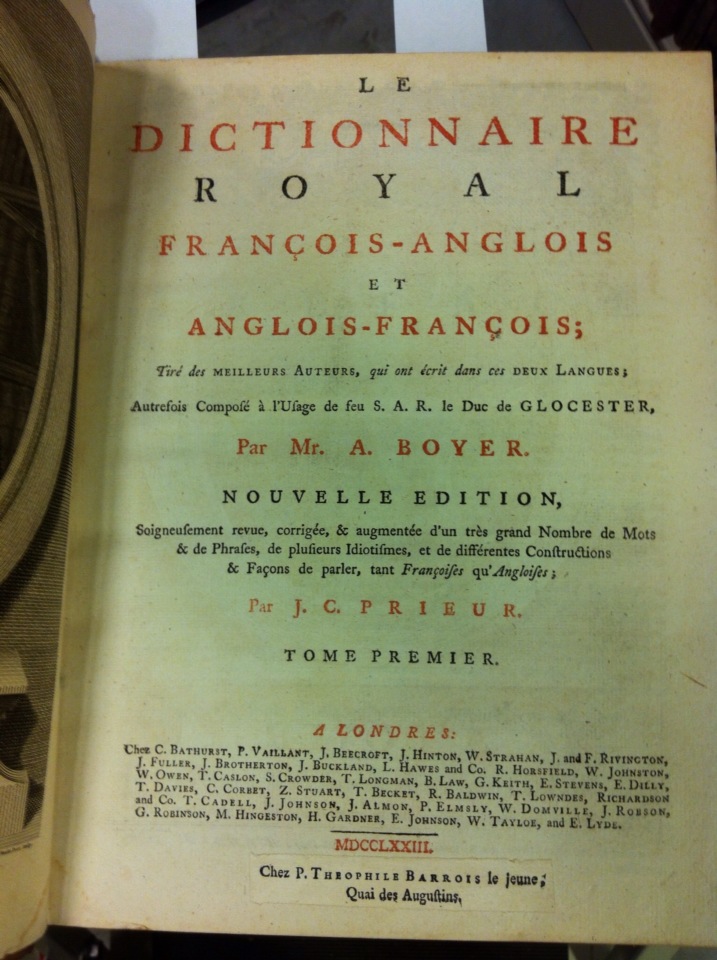

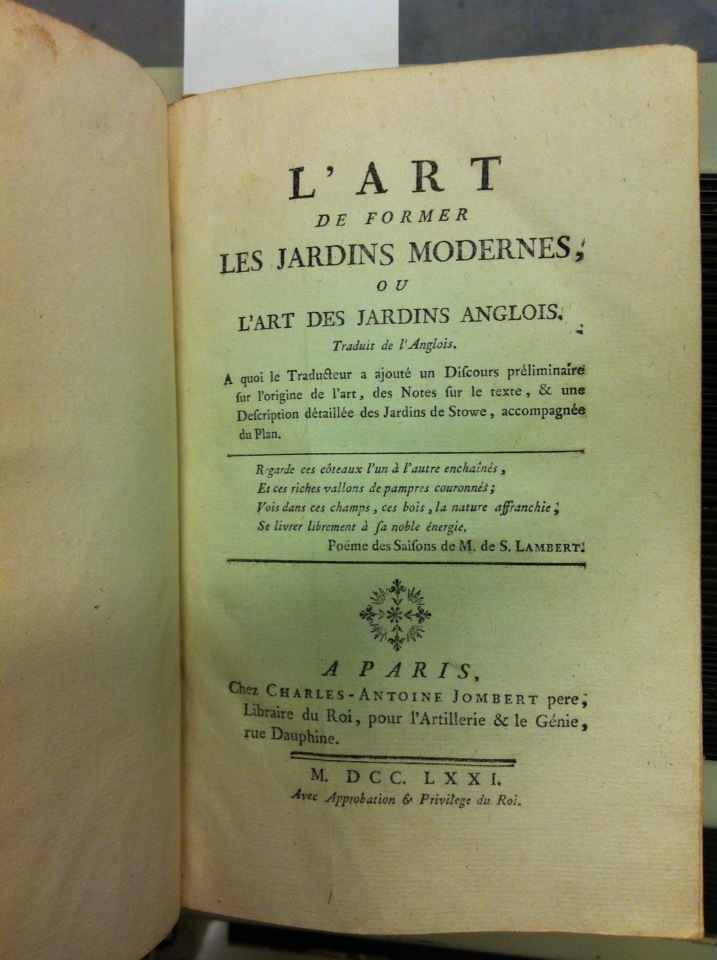

What I encountered was a revelation and delight! As I made my way systematically through the bookcase, a pattern slowly but unmistakably emerged. This was not a miscellaneous assortment of old books, but a complementary collection of rare (some extremely rare) and early works of gothic literature, many in English, augmented by various 18th-and 19th-century source materials used and cited in Maurice’s scholarly writings. The supplementary material included such works as Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Idea of the Sublime and the Beautiful (London, 1801), and Edward Mangin’s An Essay on Light Reading, as it May be Supposed to Influence Moral Conduct and Literary Taste (London, 1808). Maurice’s copy of the Dictionnaire royal françois-anglois, et anglois-françois (London, 1773) would have been an invaluable resource for study of translations, and then there was L’Art de former les jardins modernes; ou l’art des jardins anglois (Paris, 1771). What gothic novel doesn’t have a garden as a significant “setting”!

What I encountered was a revelation and delight! As I made my way systematically through the bookcase, a pattern slowly but unmistakably emerged. This was not a miscellaneous assortment of old books, but a complementary collection of rare (some extremely rare) and early works of gothic literature, many in English, augmented by various 18th-and 19th-century source materials used and cited in Maurice’s scholarly writings. The supplementary material included such works as Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Idea of the Sublime and the Beautiful (London, 1801), and Edward Mangin’s An Essay on Light Reading, as it May be Supposed to Influence Moral Conduct and Literary Taste (London, 1808). Maurice’s copy of the Dictionnaire royal françois-anglois, et anglois-françois (London, 1773) would have been an invaluable resource for study of translations, and then there was L’Art de former les jardins modernes; ou l’art des jardins anglois (Paris, 1771). What gothic novel doesn’t have a garden as a significant “setting”!

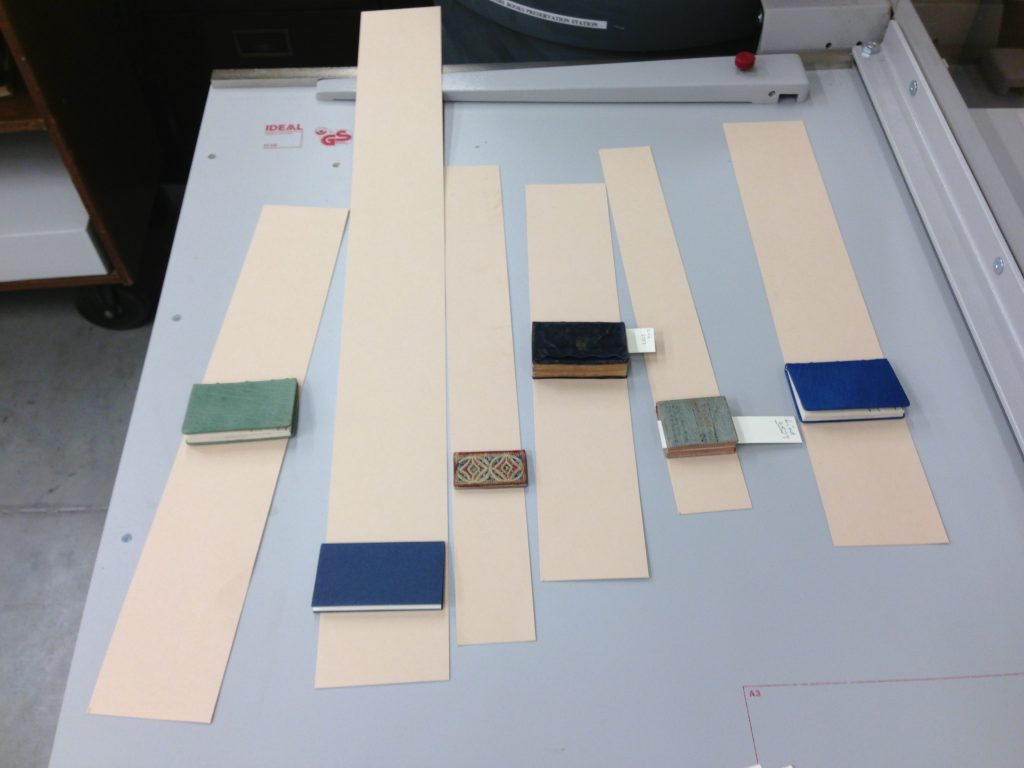

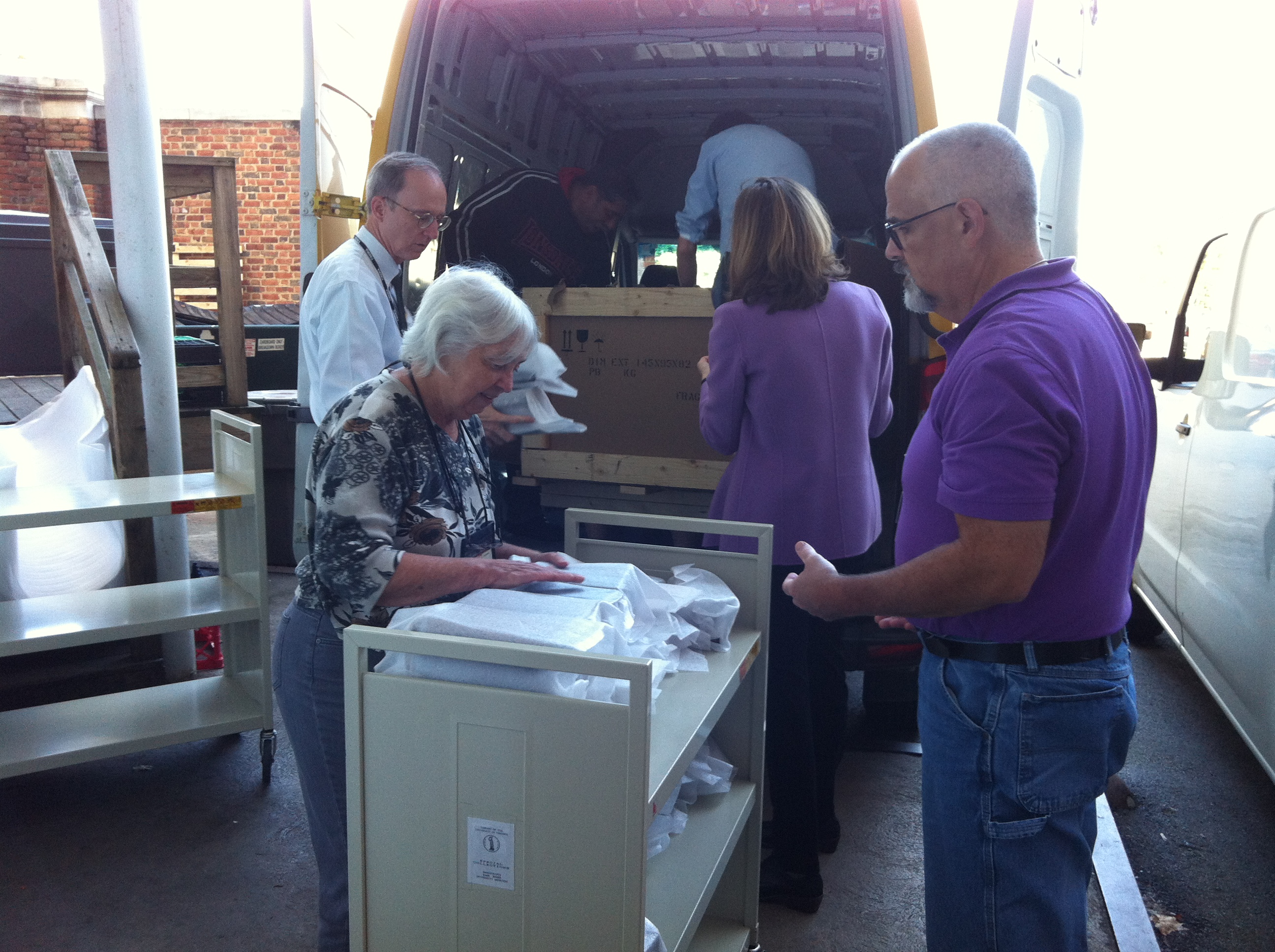

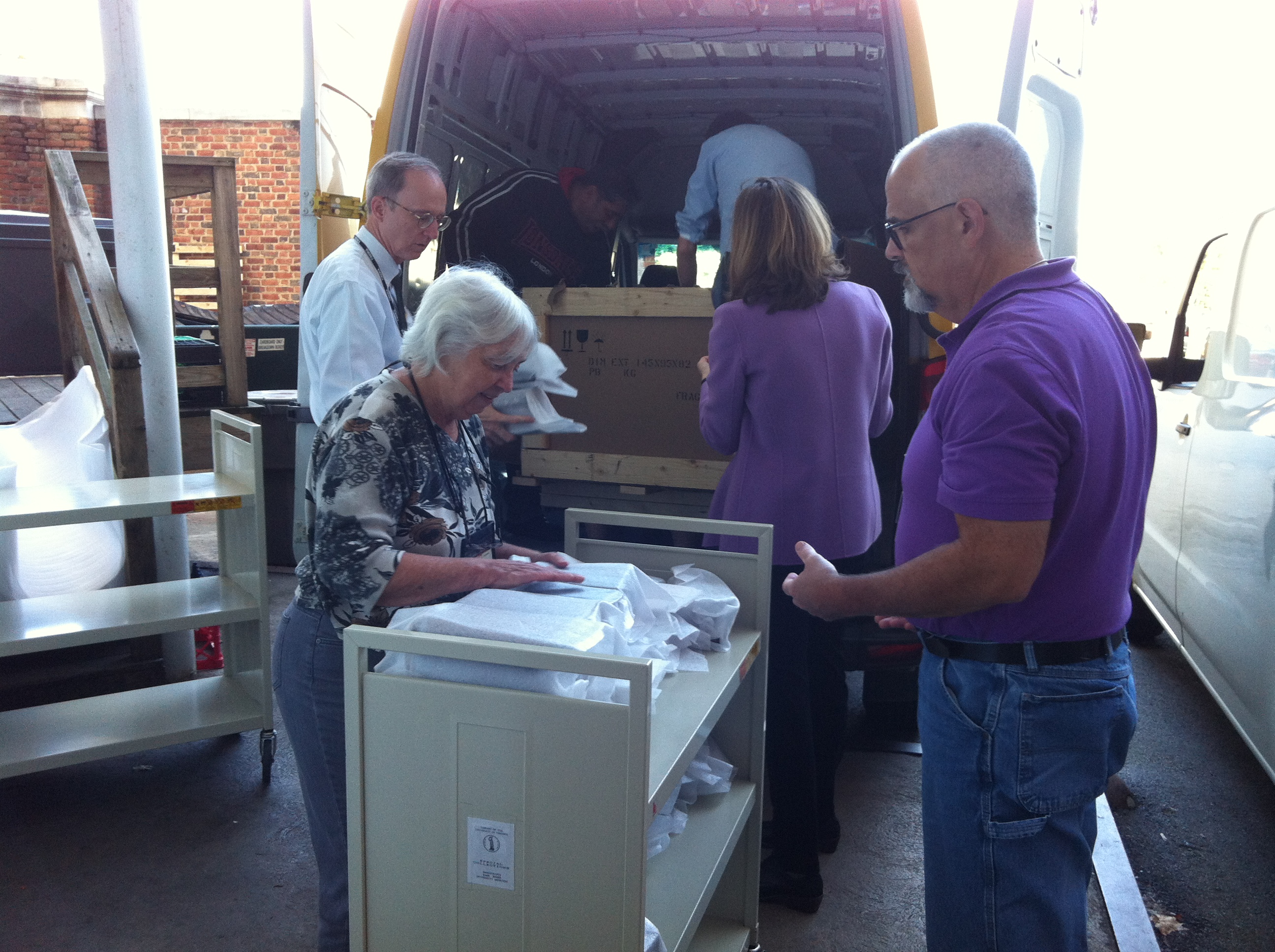

We were delighted by the new discoveries, and the possibilities that this expanded universe of resources would offer to students of gothic and related themes. It was quickly decided that virtually the entire contents of the bookcase would be packed and shipped to Charlottesville. In due course, and with only the usual customs and other delays, the collection arrived last fall at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, where it now waits patiently in the cataloging queue.

We were delighted by the new discoveries, and the possibilities that this expanded universe of resources would offer to students of gothic and related themes. It was quickly decided that virtually the entire contents of the bookcase would be packed and shipped to Charlottesville. In due course, and with only the usual customs and other delays, the collection arrived last fall at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, where it now waits patiently in the cataloging queue.

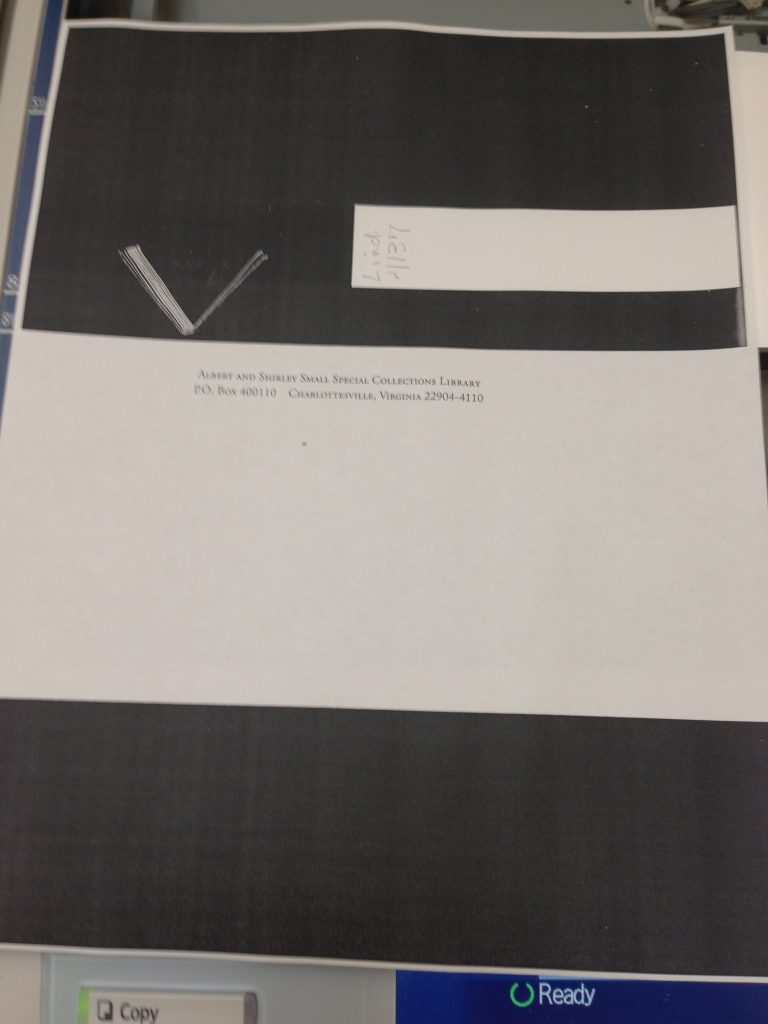

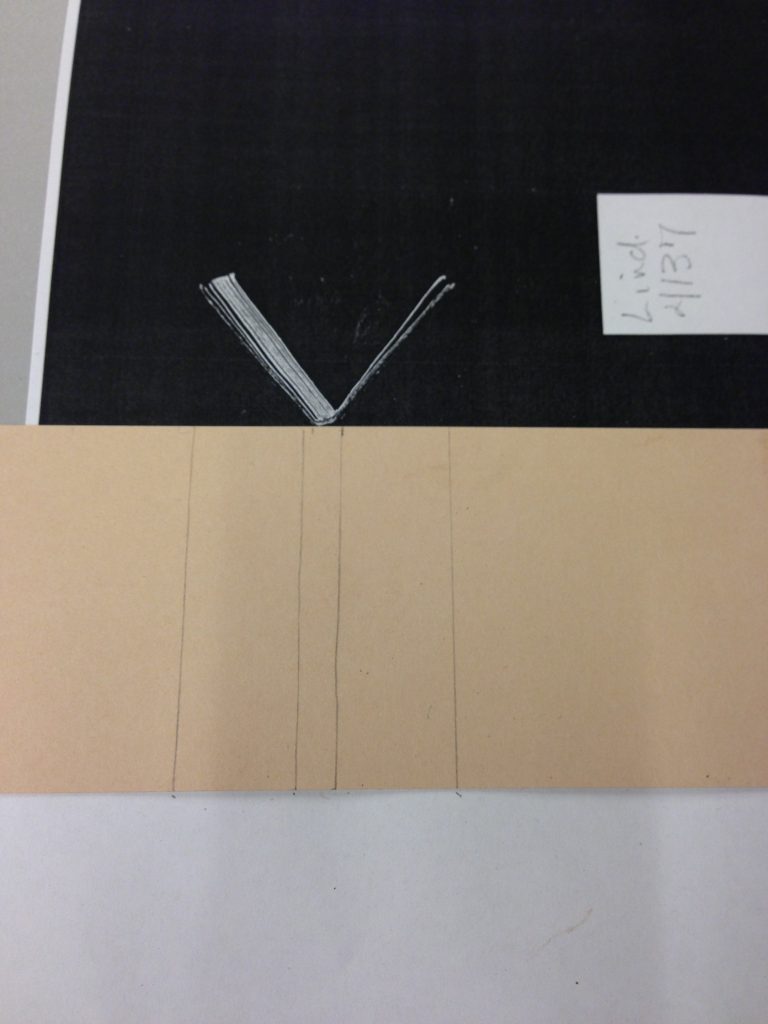

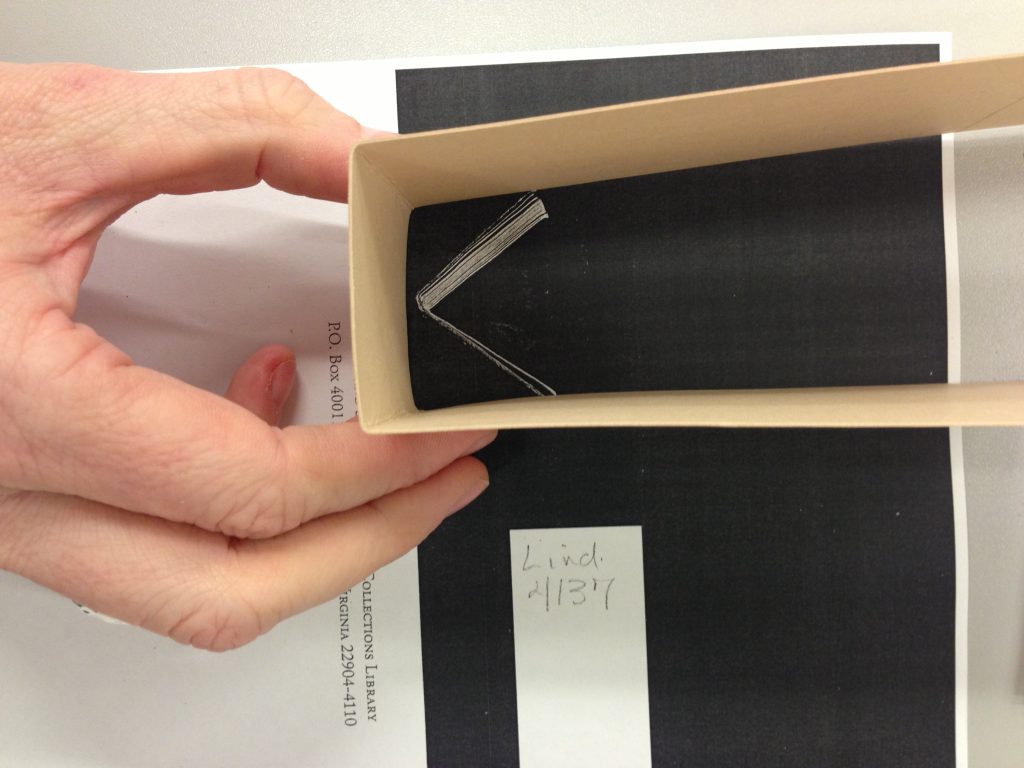

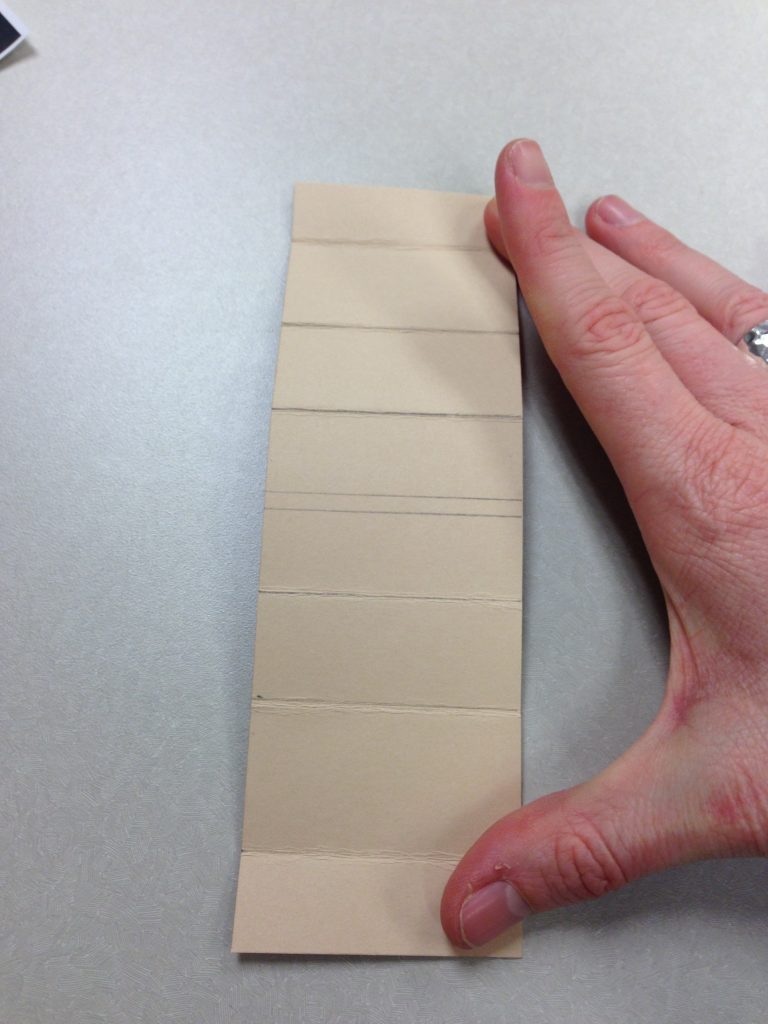

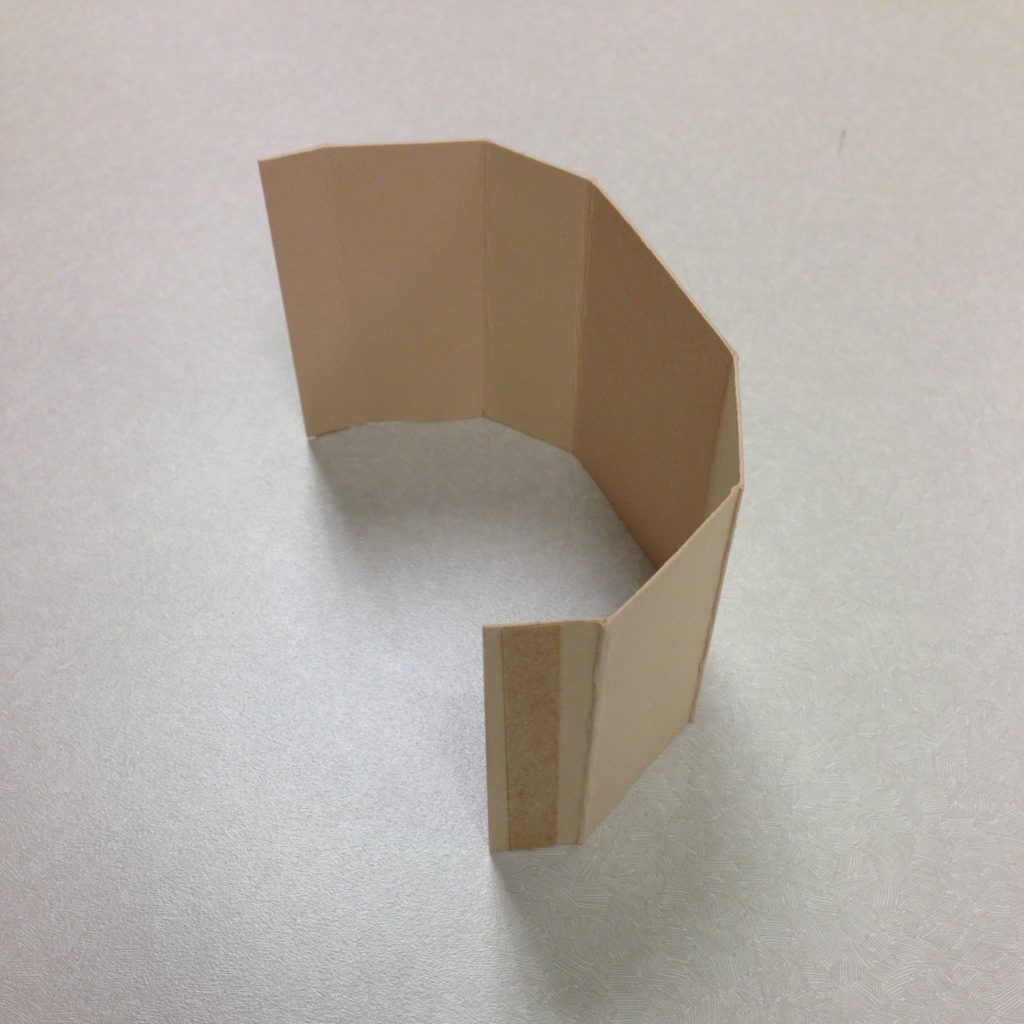

Special Collections staff unload the Maurice Lévy French Gothic collection, October 9, 2012.

The Lévy family, for their part, was delighted and relieved to see Maurice’s treasured “rare book cabinet” transferred virtually intact to its new and permanent home at U. Va., where it will be consulted by future generations of students and scholars of the “gothic,” and serve as a permanent tribute to Maurice’s life and career as a scholar, teacher, and mentor. Nothing, they felt, would have pleased Maurice more. And like many other collections “under Grounds,” the Lévy collection also serves as an instructive reminder of how great library collections may be built, to a significant degree, by the cumulative legacies of chance encounters.

(A future posting will feature more highlights from the Lévy collection.)

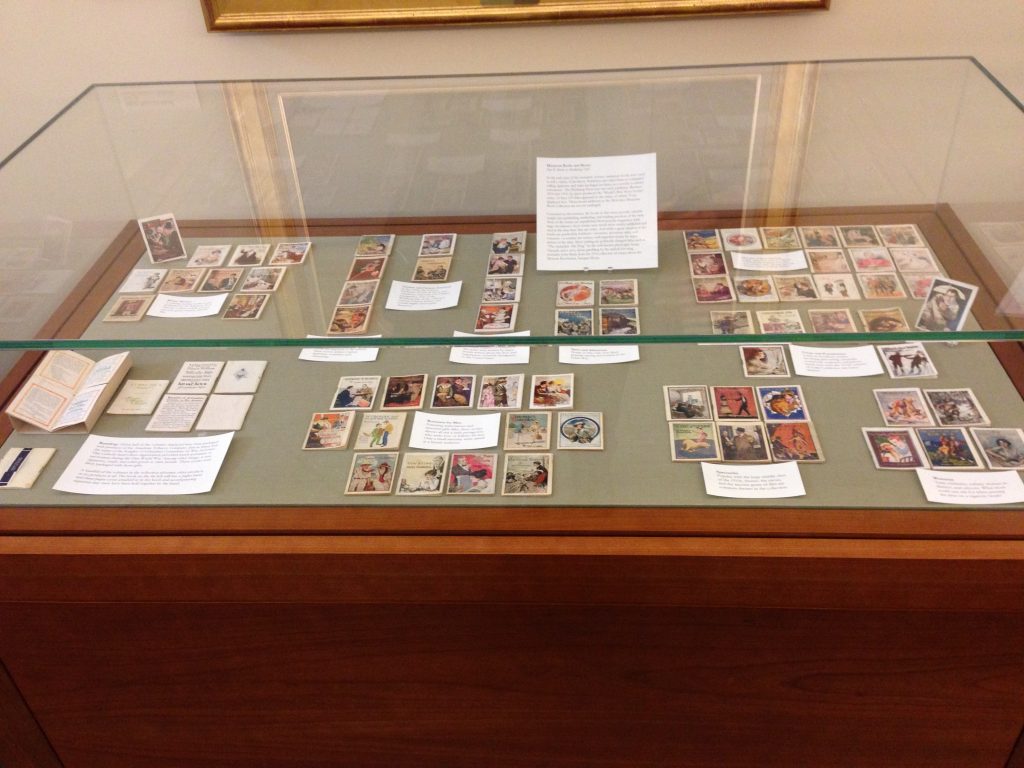

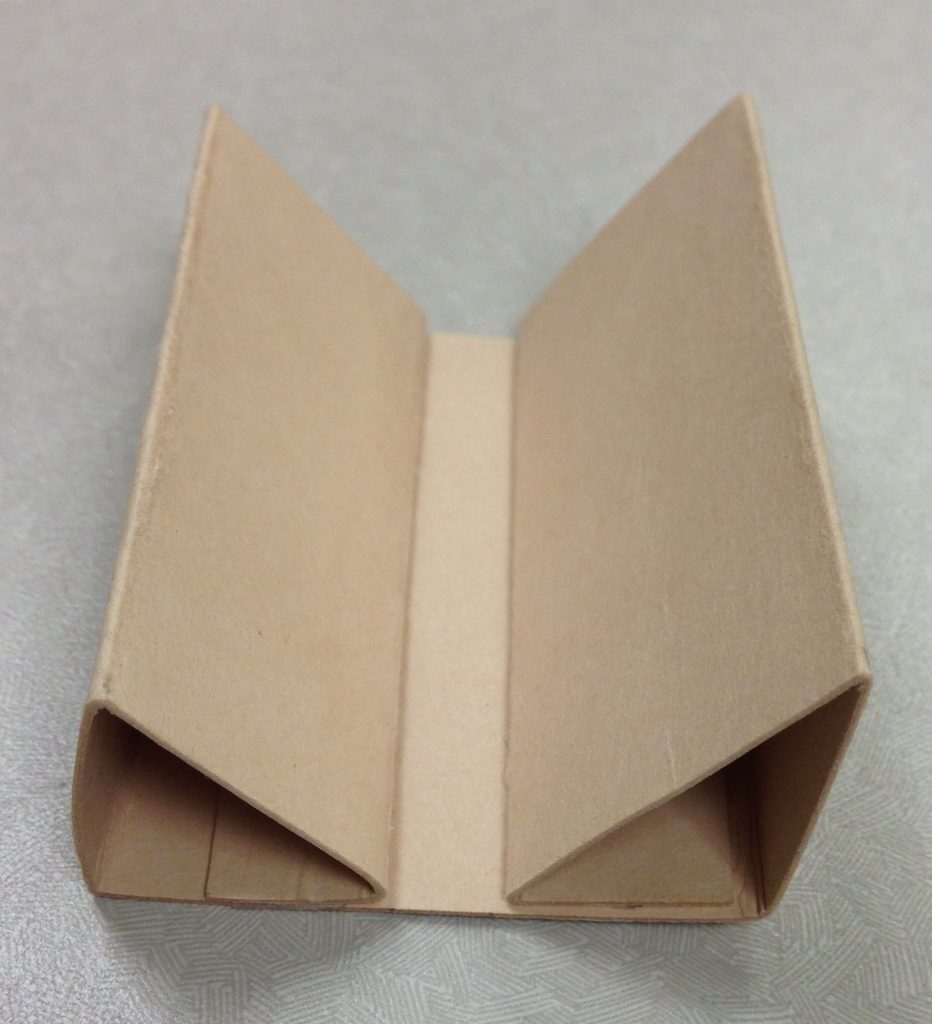

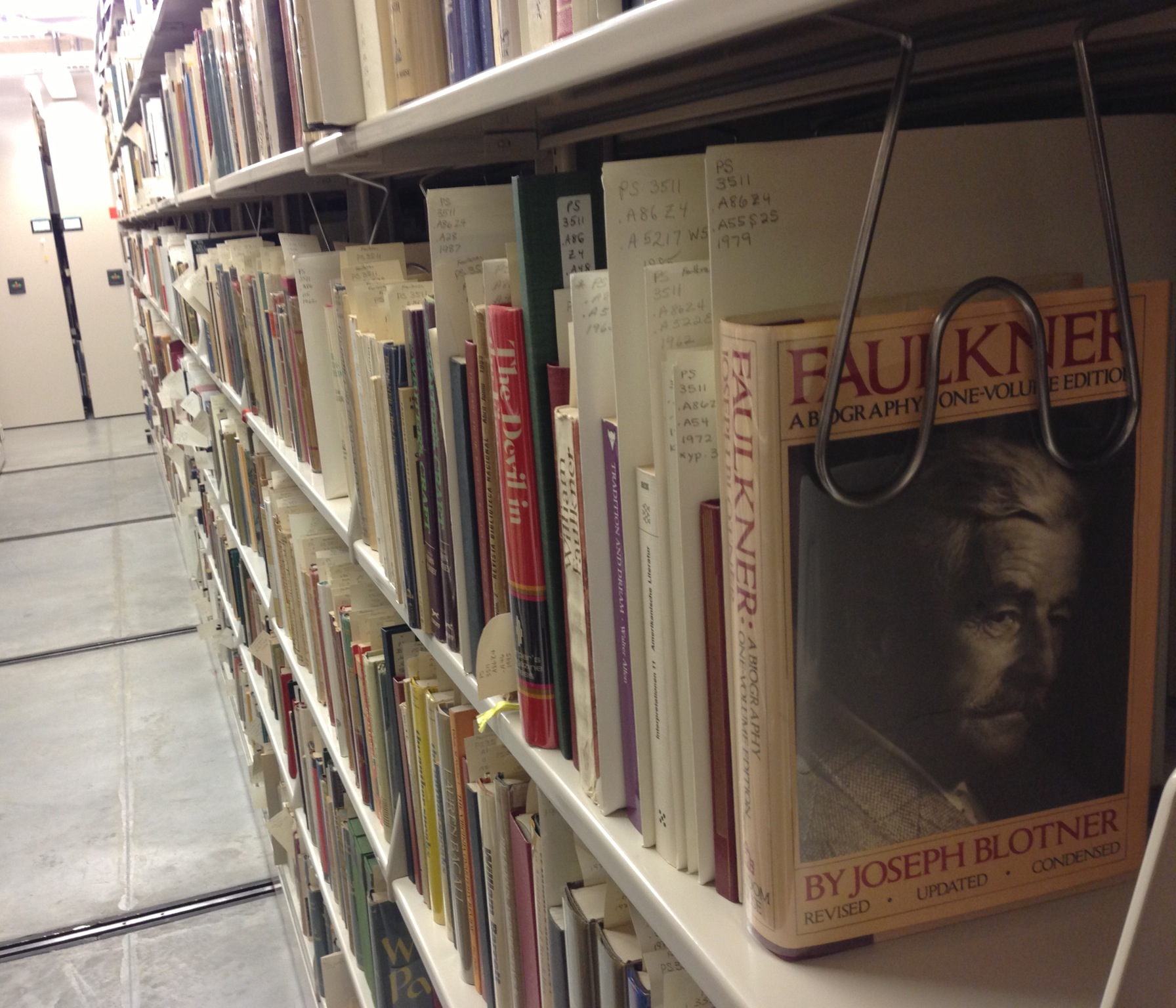

The Maurice Lévy French Gothic collection as it looks today, under Grounds.