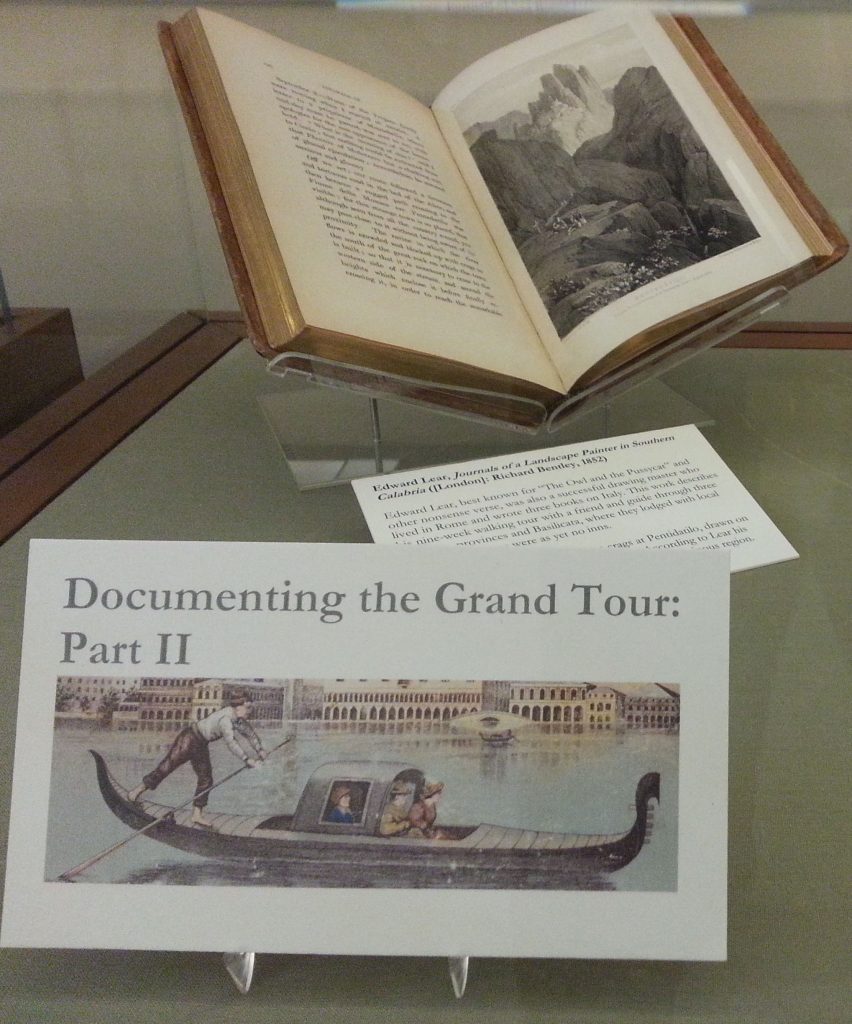

This is the final in a series of three posts, spotlighting the mini-exhibitions of students from USEM 1580: Researching History, Fall 2015.

***

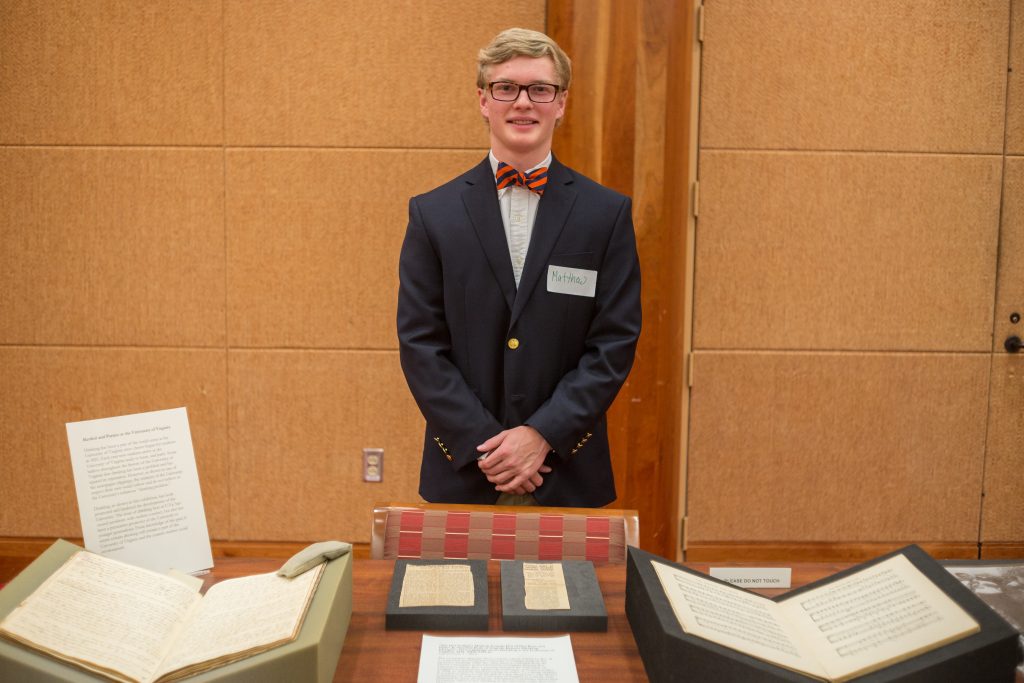

Matthew Parker, First-Year Student

Alcohol and Parties at the University of Virginia

Drinking has been a part of the social scene at the University of Virginia since classes began for students in 1825. Each year new students arrive at the University of Virginia ready to learn, and party. Some believe throughout the history of the University of Virginia that drinking has been a problem and has injured its reputation. However, as shown in one of the newspaper clippings, the students of the University respect their own social culture and do not believe in the University’s infamous “drinking problem.”

Drinking, as shown in this exhibition, has both promoted and hindered the development of the University. The issue of drinking here at U.Va. has caused problems with student conduct, but also has been a persuasive promoter of the University to younger generations. From knowledge of the past, it seems certain drinking will remain a part of the University of Virginia and the current student social environment.

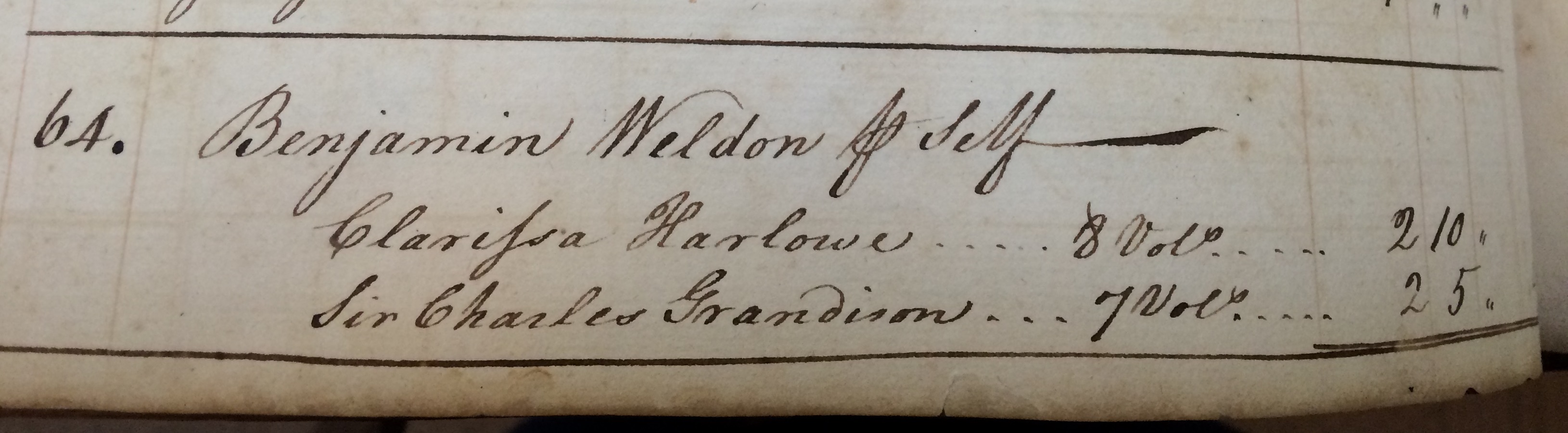

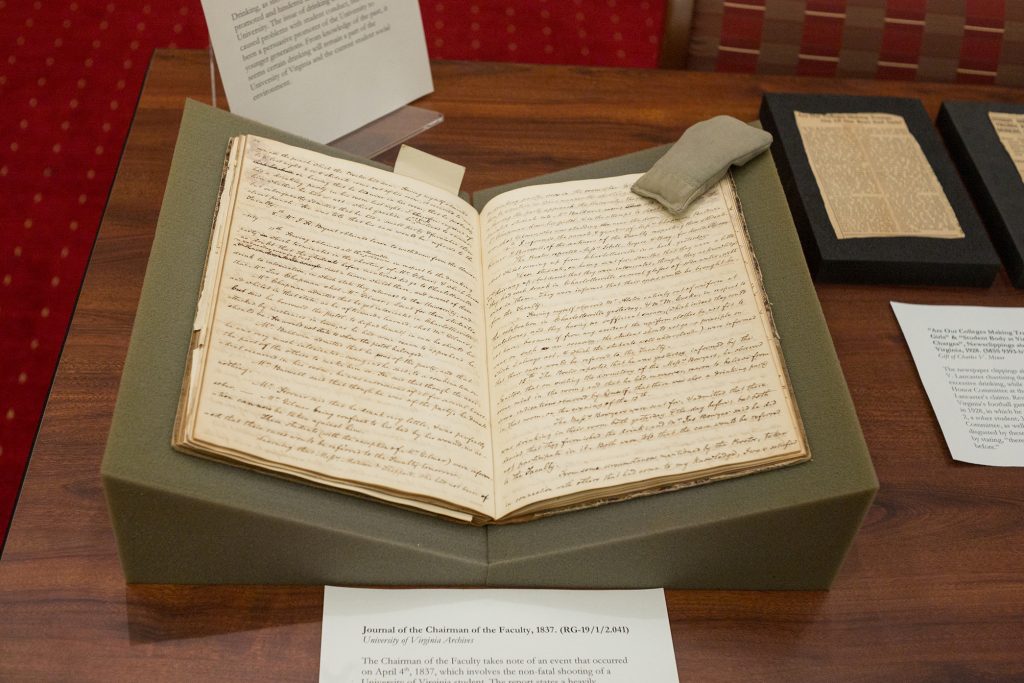

Journal of the Chairman of the Faculty, 1837. (RG-19/1/2.041)

University of Virginia Archives

The Chairman of the Faculty takes note of an event that occurred on April 4th, 1837, which involves the non-fatal shooting of a University of Virginia student. The report states a heavily intoxicated student shot another fellow student inside his dormitory. The investigation of the event unfolds throughout the following weeks, and the Chairman of the Faculty writes down every aspect of the event as it becomes uncovered. On April 11th, the investigation into the shooting found all available evidence, and the Board of Visitors penalized the students involved. (Photograph by Sanjay Suchak, November 17, 2015)

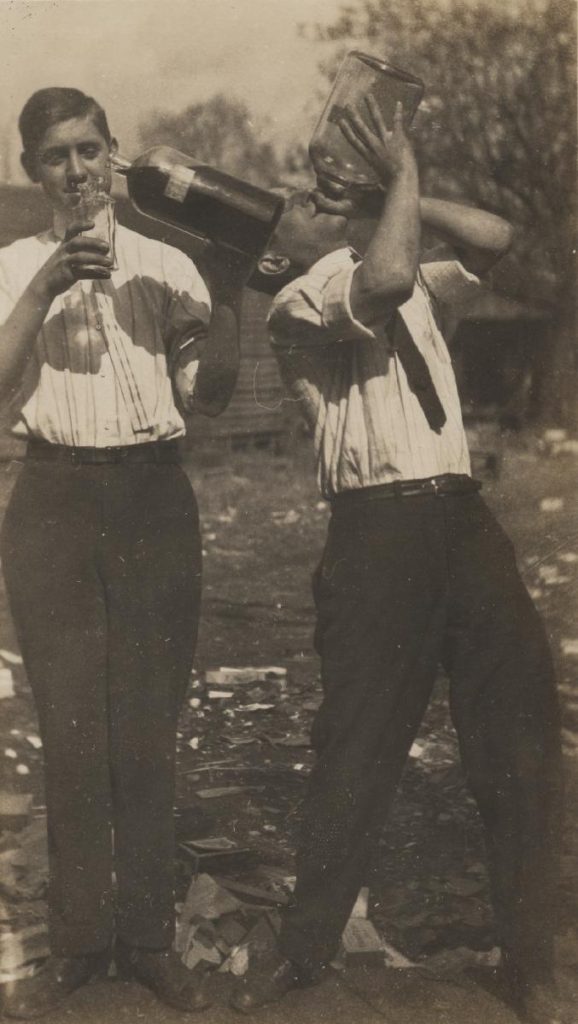

“Guys Drinking.” Hot Foot Society, 1903. (RG-23/46/1.971)

University of Virginia Visual History Collection

This photograph shows two University of Virginia students drinking alcohol straight from handles. These students were members of a society at the University of Virginia, formally known as the Hot Foot Society. The Hot Foot Society, which began in 1902, was known for its heavy participation in drinking. After their first suspension in 1908, the Hot Foot Society decided to disband in 1911, following a prank which resulted in the expulsion of four members and one-year suspensions for another four members. In 1913, the society reincarnated itself into the IMP Society, which remains active today. (Image by Digital Production Services)

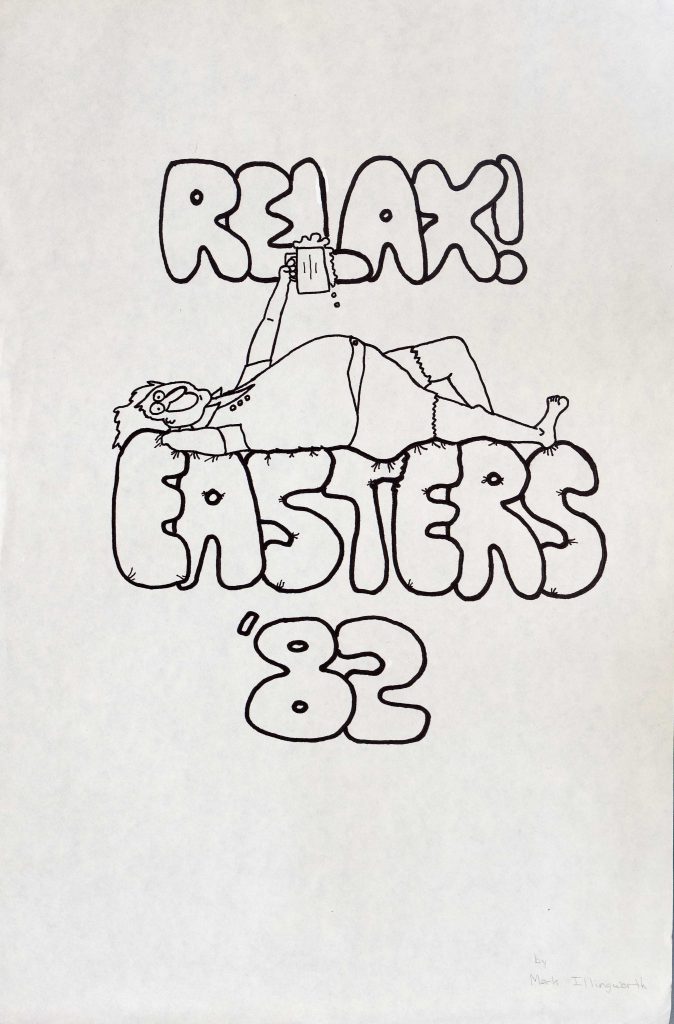

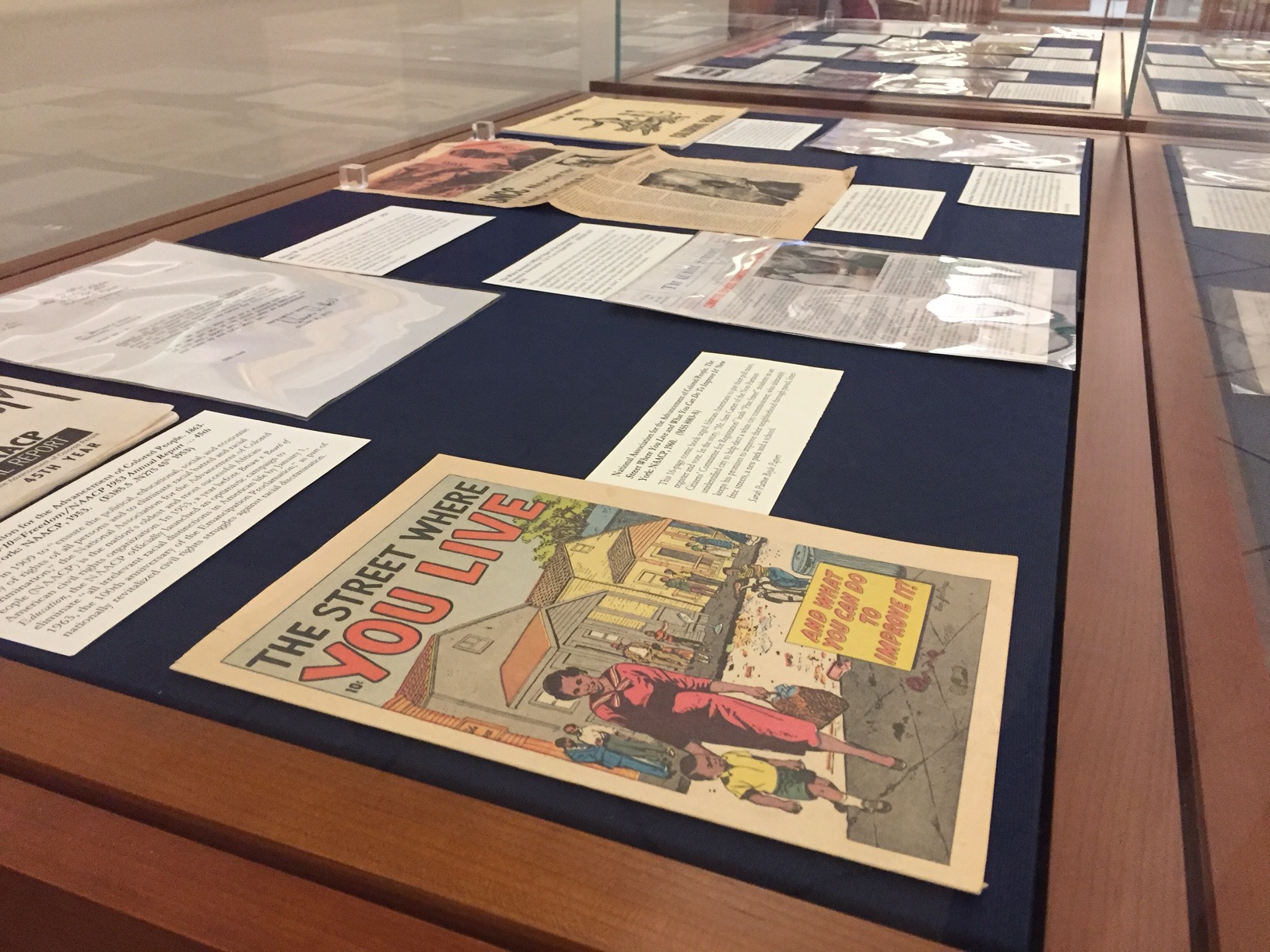

Mark Illingworth. Easters T-shirt Contest Entry, 1982. (RG-23/17/3.881)

University of Virginia Archives

The logo shown above is one of many entries for the Easters T-shirt Contest in 1982. Easters started as a formal dance in the late 19th century, but slowly transitioned into a massive party at the University of Virginia that reached its prime in the 1970s. During the 1970s, the Easters party took place on the rugby field beside Rugby Road, known as Mad Bowl. Thousands of students would file into the field and drink. All the surrounding fraternities would participate in the party and supply a large amount of the alcohol. Many of the logos for the t-shirt contest contain depictions of alcohol in some fashion. The winning entry, however, did not depict alcohol in the illustration. (Image by Penny White)

***

Grant Gossage, Second-Year Student

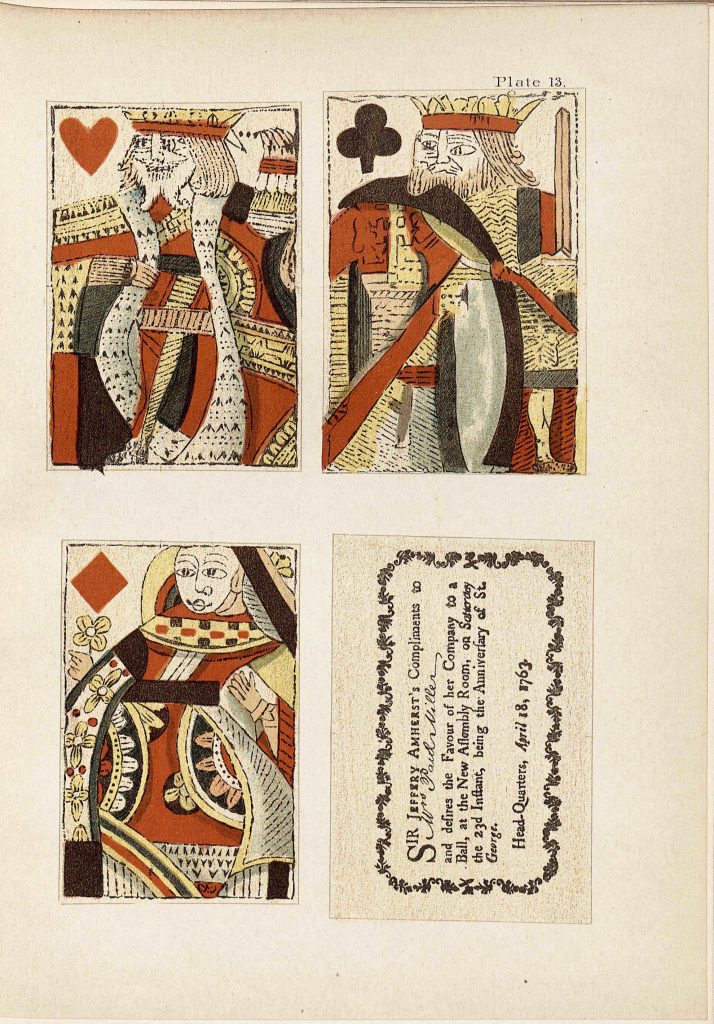

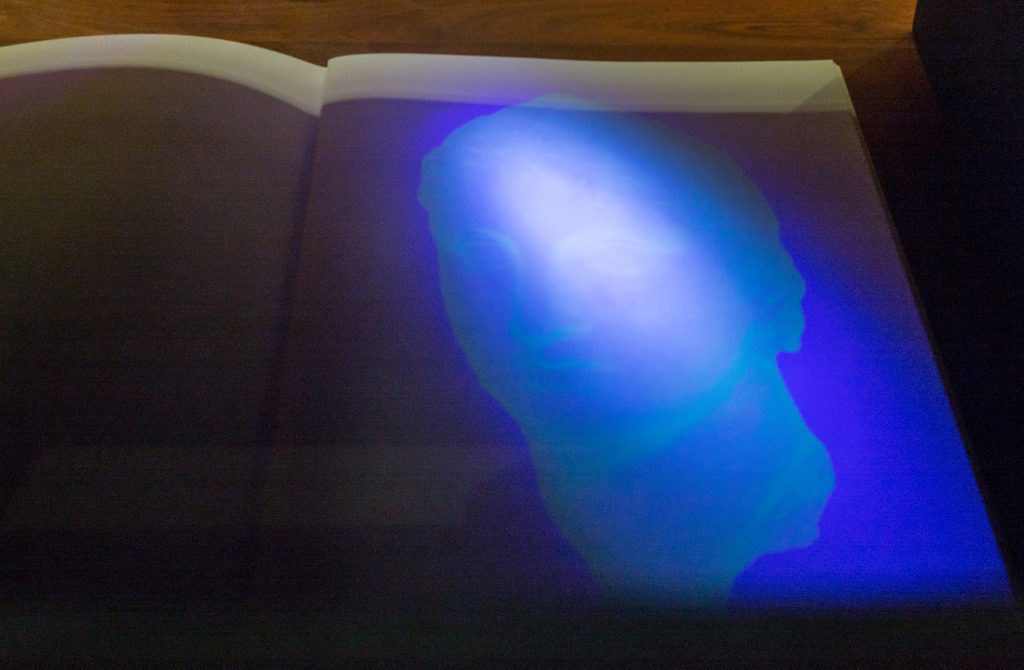

Mrs. John King Van Renssalaer. The Devil’s Picture Book: A History of Playing Cards. New York, Dodd, Mead and Company, ca. 1890. (Z5481.V35 1890)

Gift of the Stone family

A storied history of playing cards presented in this book by Van Renssalaer created an aura around the act of gambling in the 19th century and beyond. The devil’s picture book depicts 18th century French, English, American, and German playing cards as artful possessions of the aristocracy. Students at the University of Virginia in the 19th century were mainly southern gentry. They wore over-the-top clothing until the uniform law. They fought to preserve their honor. They drank and chased women to impress. They gambled to reveal their wealth and to take power from others. The young men venerated the noble past of gambling that the images and text in this book exhibit. (Image by Penny White)

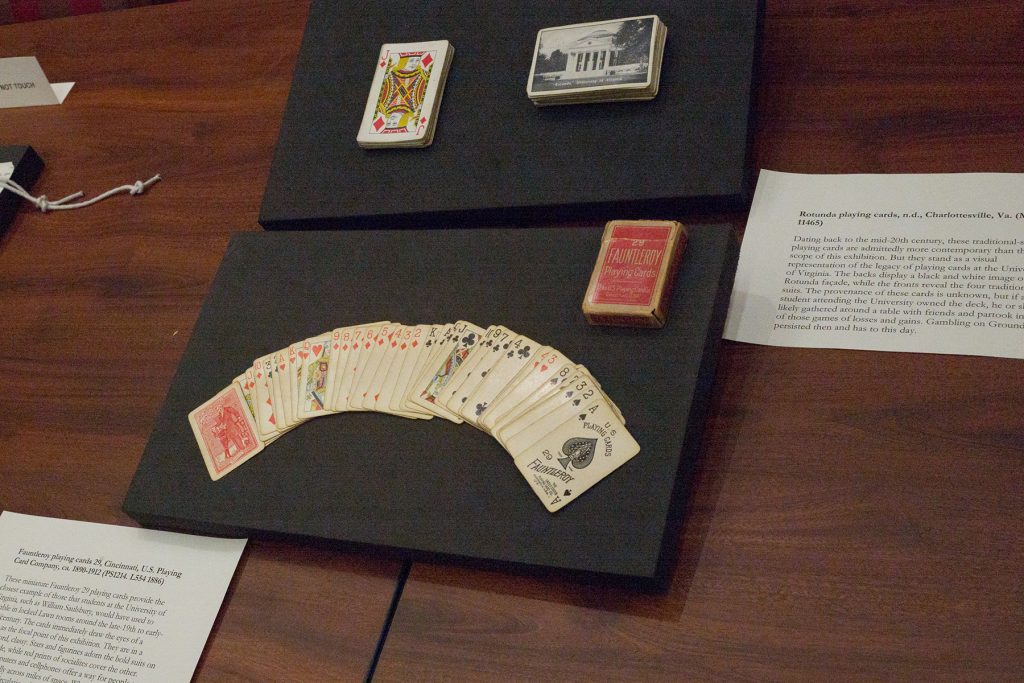

Fauntleroy playing cards 29, Cincinnati, U.S. Playing Card Company, ca. 1890-1912 (PS1214. L554 1886), (Foreground).

These miniature Fauntleroy 29 playing cards provide the closest example of those that students at the University of Virginia, such as William Saulsbury, would have used to gamble in locked Lawn rooms around the late-19th to early-20th century. The cards immediately draw the eyes of a viewer as the focal point of this exhibition. They are in a single word, classy. Stars and figurines adorn the bold suits on the one side, while red prints of socialites cover the other. Today, computers and cellphones offer a way for people to gamble virtually across miles of space. When these Fauntleroy cards were in circulation, Saulsbury and other university students gathered around a table, stared each other in the face, and went about taking money. (Photograph by Sanjay Suchak, November 17, 2015)

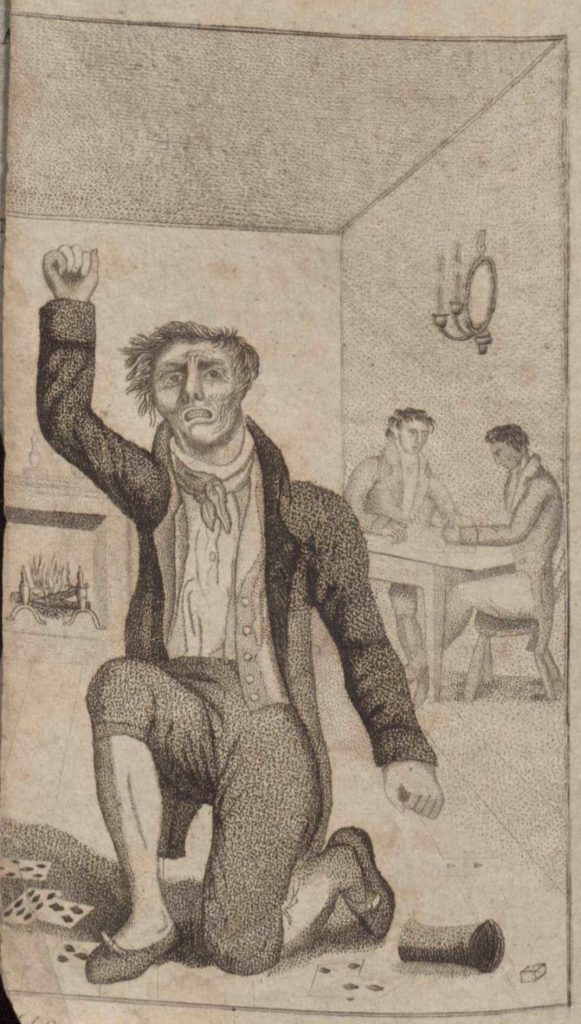

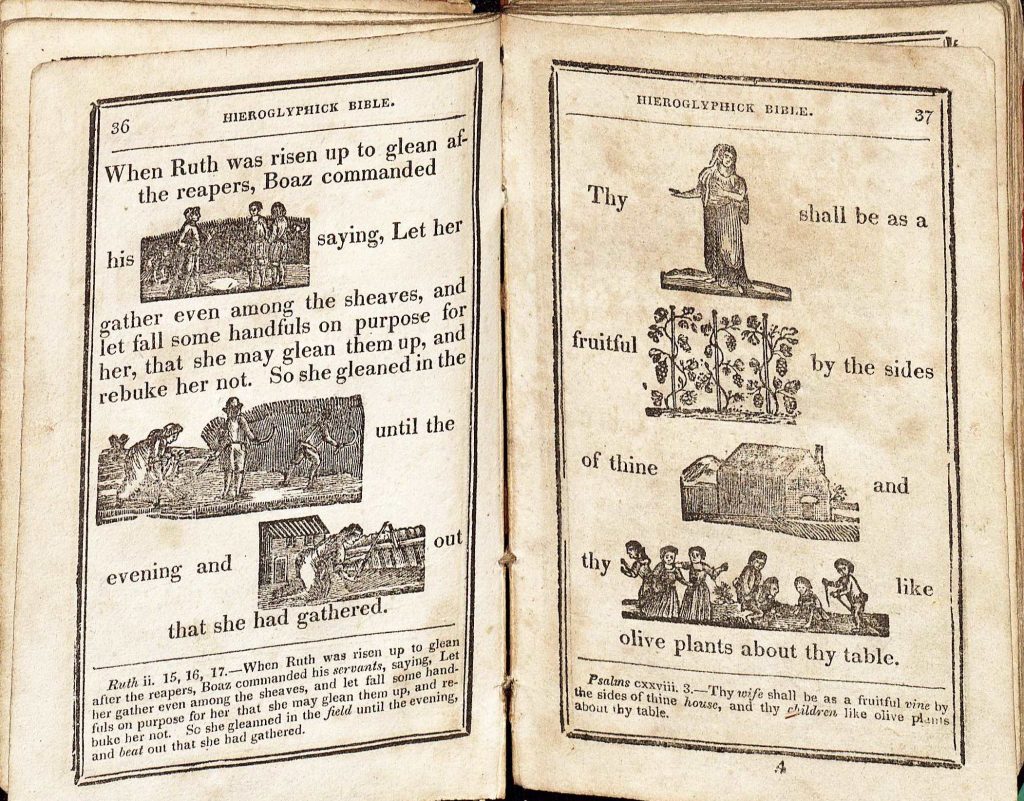

M.L. Weems. God’s revenge against gambling: Exemplified in the miserable lives and untimely deaths of a number of persons of both sexes, who had sacrificed their health, wealth, and honour, at gaming tables. Philadelphia, ca. 1822. (A1822.W43)

Around 1822, the former rector of Mount Vernon Parish, M.L. Weems wrote about the deaths of more than six individuals, which he believed was the result of gambling. His book condemns an immoral generation of gamblers as sinners before God and criminals in society. Showing a measure of empathy, Weems seeks to dissuade innocent, young people, including his son for whom he addresses the book, from falling for this temptation at gaming tables. Past the frontispiece, which depicts a deformed man on bended knee cursing cards and dice, Weems writes, “I conjure my boy to shun the gambler’s accursed trade; for its, ‘way is the way to hell, going down in the chambers of death.” (Image by Penny White)

![Joseph Hutchings purchased 8 volumes of of Shakespeare "for [his] self" (MSS 467).](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/theobalds_shakespeare.jpg)