The Harrison/Small First Floor Gallery is excited to announce our two summer exhibitions: “My Own Master: Resistance to American Slavery” and the mini-exhibition “‘Read, Weep, and Reflect’: Creating Young Abolitionists through Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” Together these two exhibitions extend some of the themes explored in our Harrison Gallery exhibition, “Who Shall Tell the Story: Voices of Civil War Virginia. ” Come in out of the heat and spend some time with these marvelous exhibitions. Some images to tempt you follow…

The larger exhibition, “My Own Master,” is of particular note because it is the first exhibition in memory that the University of Virginia Library has mounted on the topic of slavery (a fact discovered in discussions with long-time Special Collections staff). Though artifacts relating to slavery have been included and the topic discussed in past exhibitions, slavery has not been the sole subject of an exhibition here. We are very pleased to end that tradition this summer. Even more exciting, in 2018 we will mount a major exhibition on the topic of slavery at the University of Virginia in the Harrison Gallery, in support of the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University.

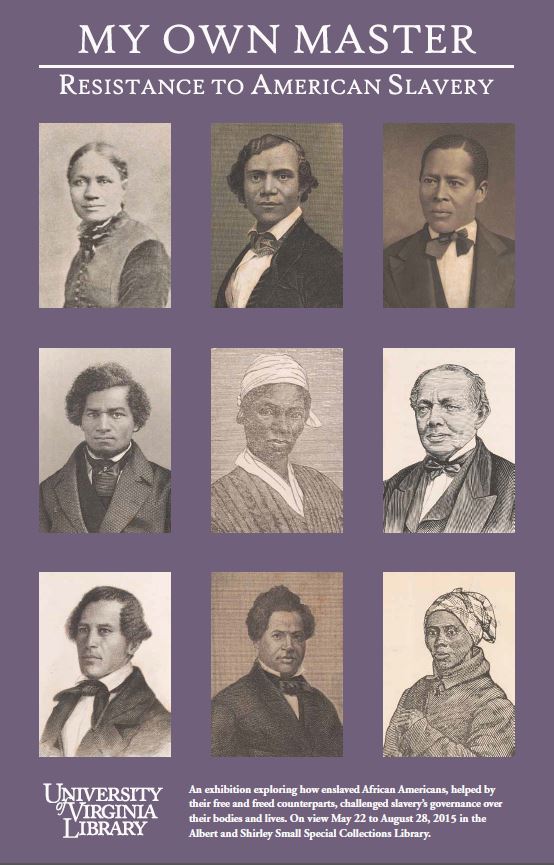

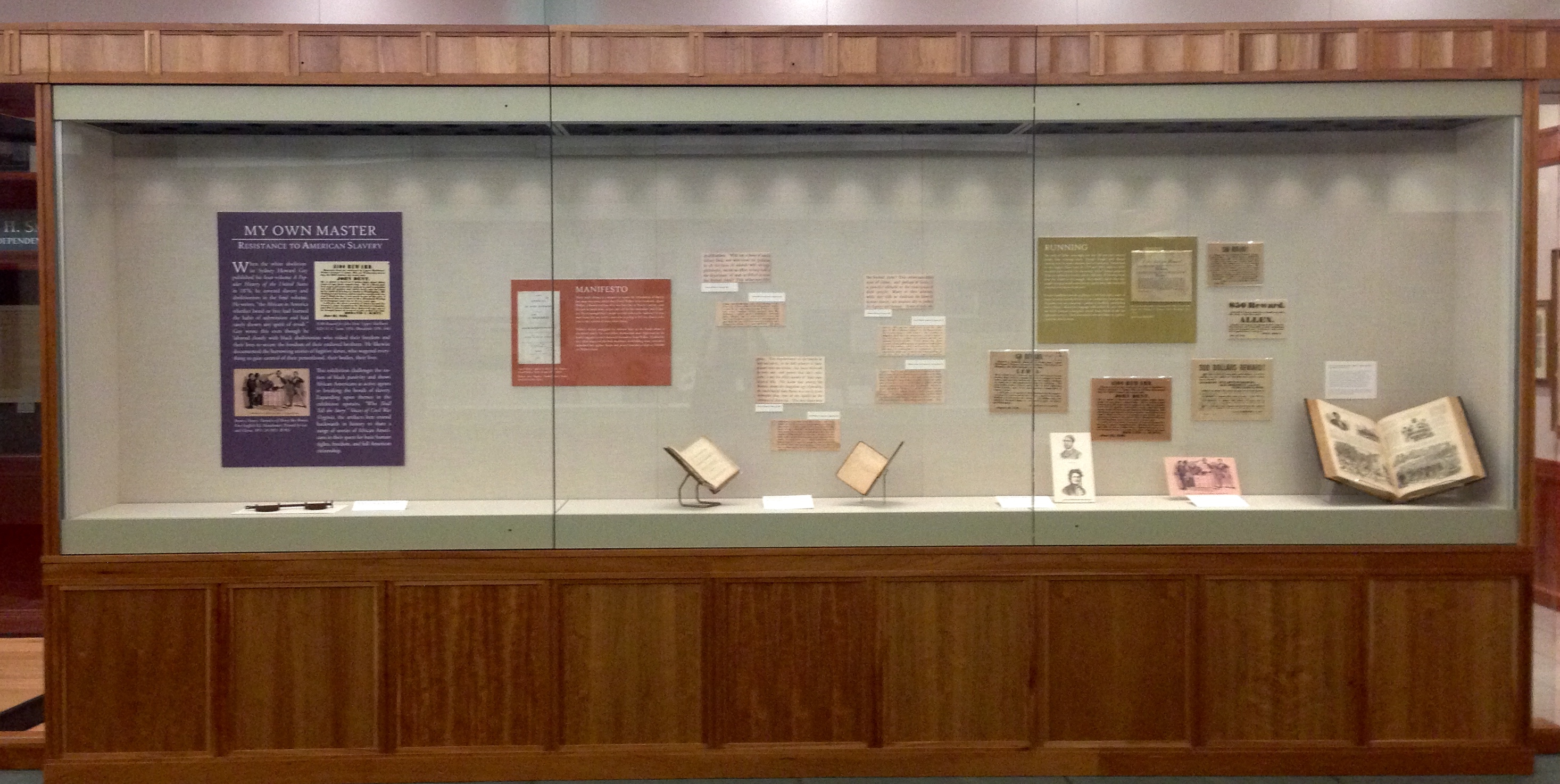

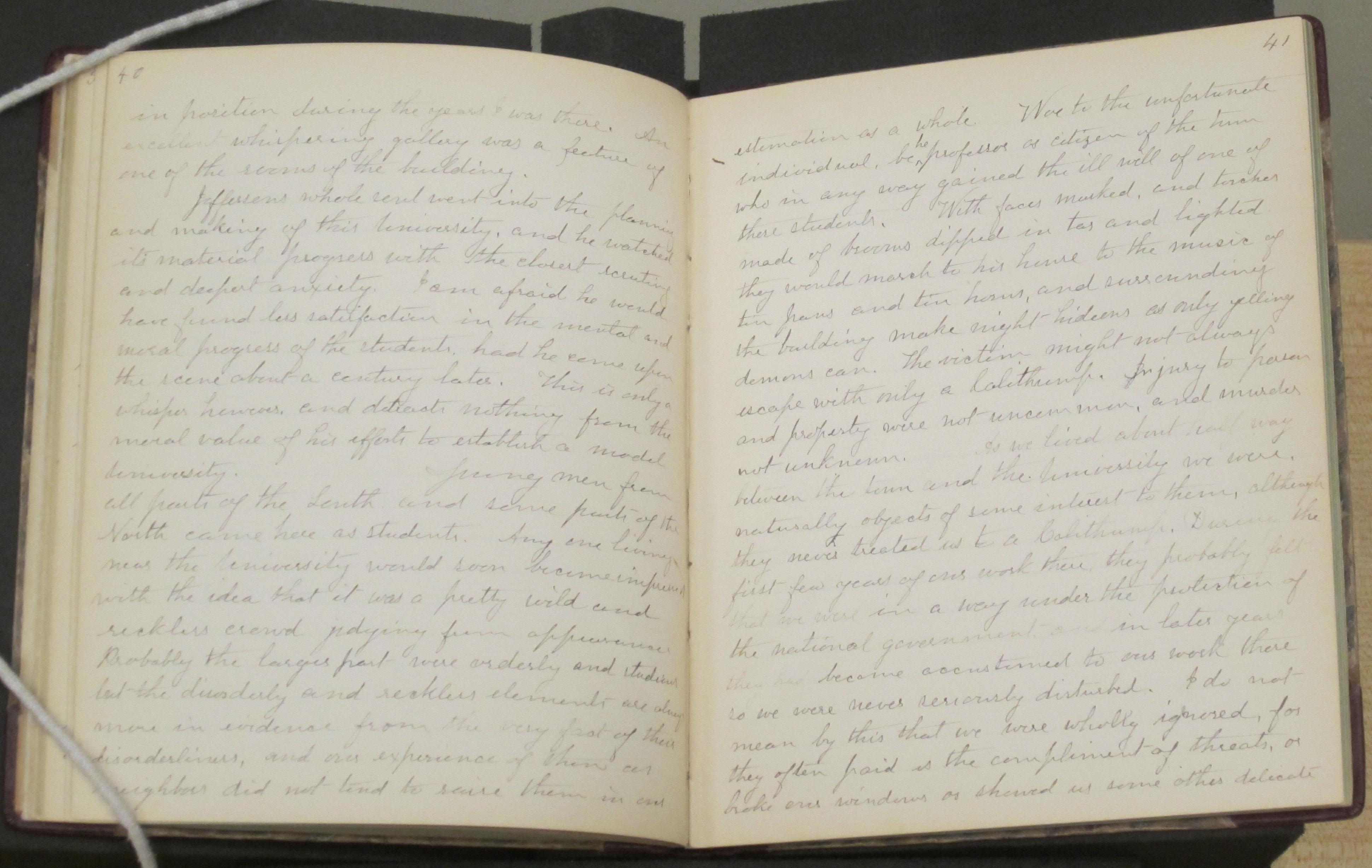

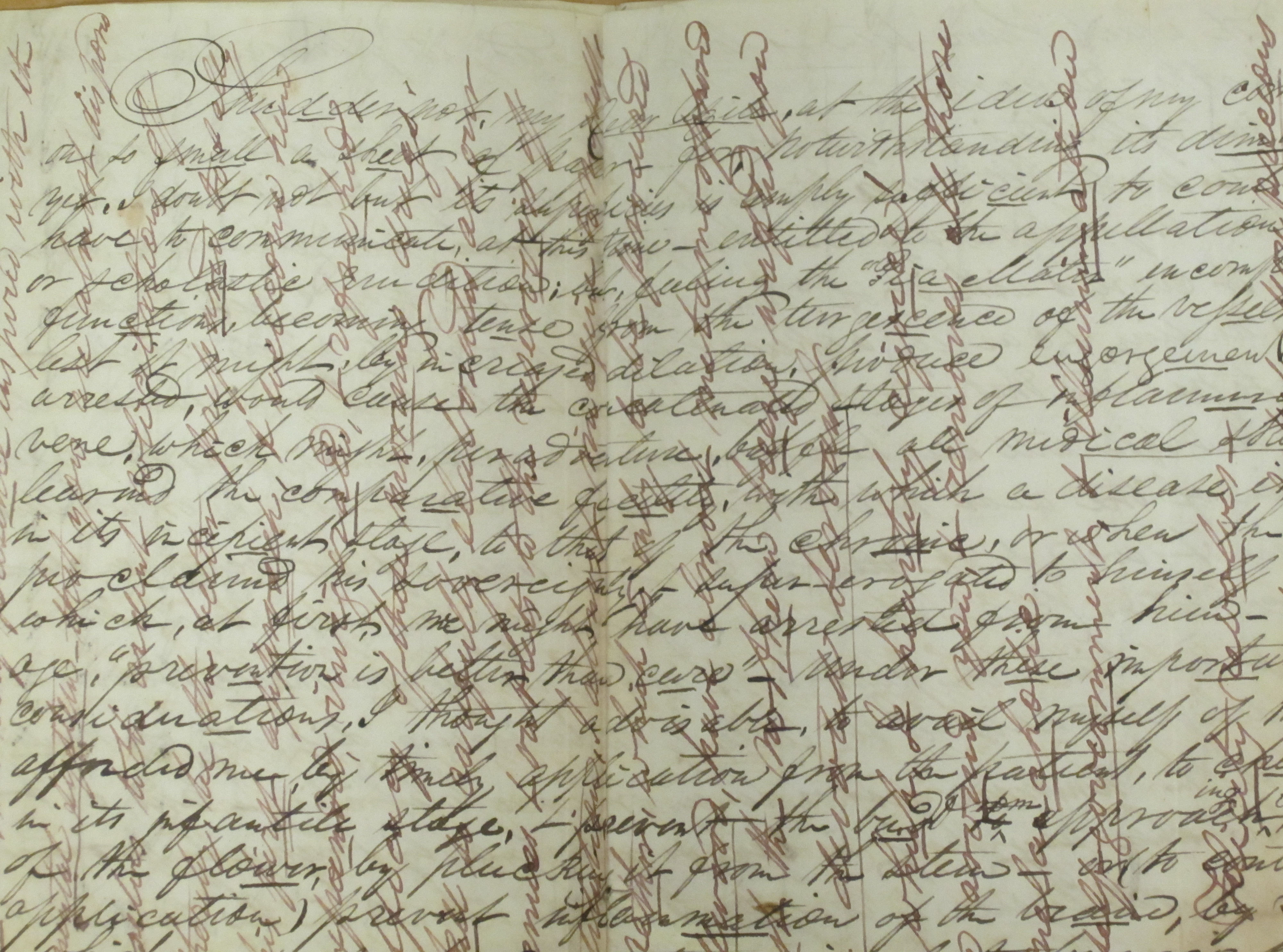

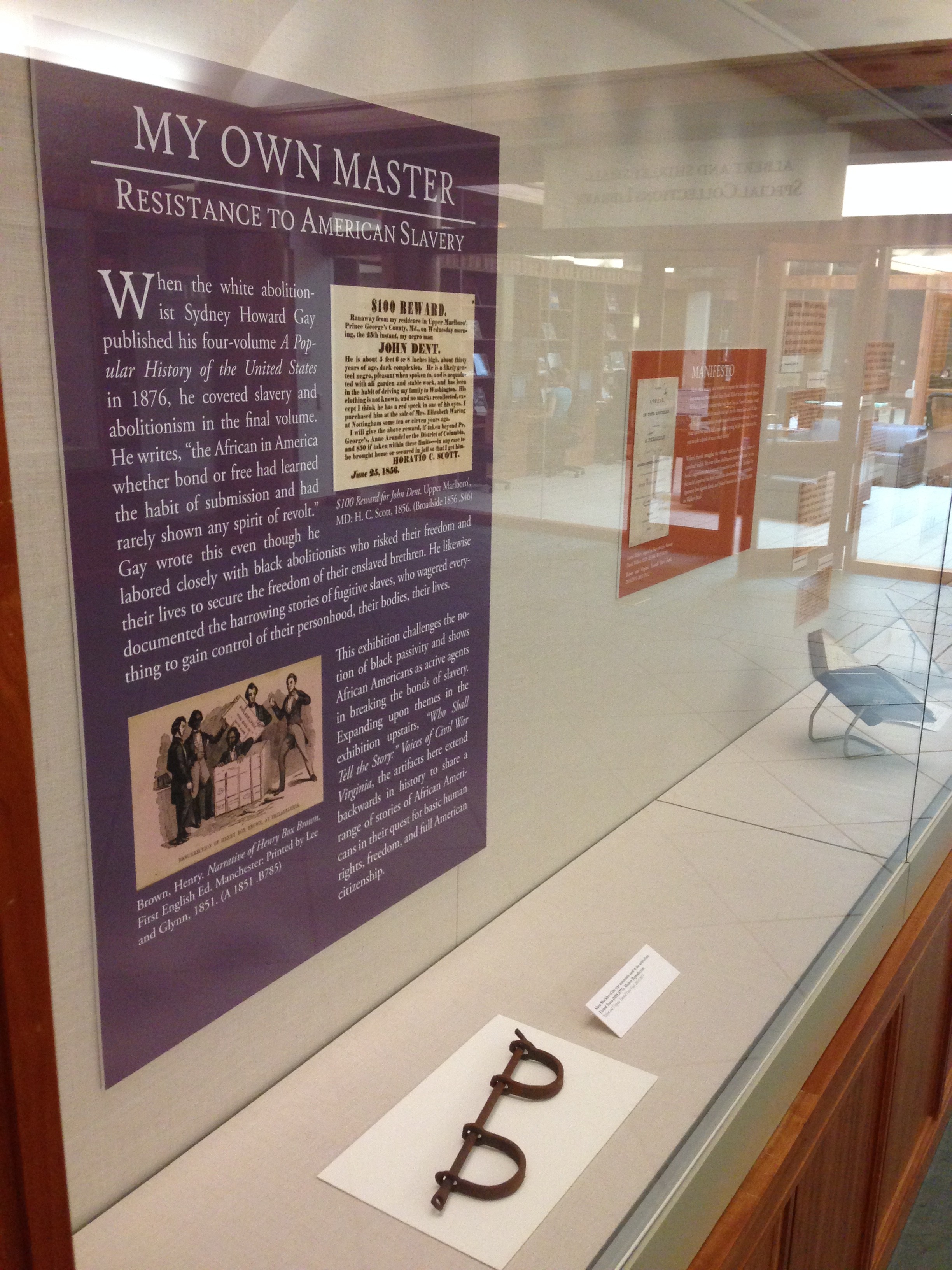

“My Own Master” showcases thirty remarkable items from the collections demonstrating some of the ways that blacks–slave, free, and freed–fought against slavery. Curator Petrina Jackson describes the exhibition’s project as follows: “When the white abolitionist Sydney Howard Gay published his four-volume A Popular History of the United States in 1876, he covered slavery and abolitionism in the final volume. He wrote, ‘the African in America whether bond or free had learned the habit of submission and had rarely shown any spirit of revolt.’ Gay wrote this even though he labored closely with black abolitionists who risked their freedom and their lives to secure the freedom of their enslaved brethren. He likewise documented the harrowing stories of fugitive slaves, who wagered everything to gain control of their personhood, their bodies, their lives. “My Own Master” challenges the notion of black passivity and shows African Americans as active agents in breaking the bonds of slavery.”

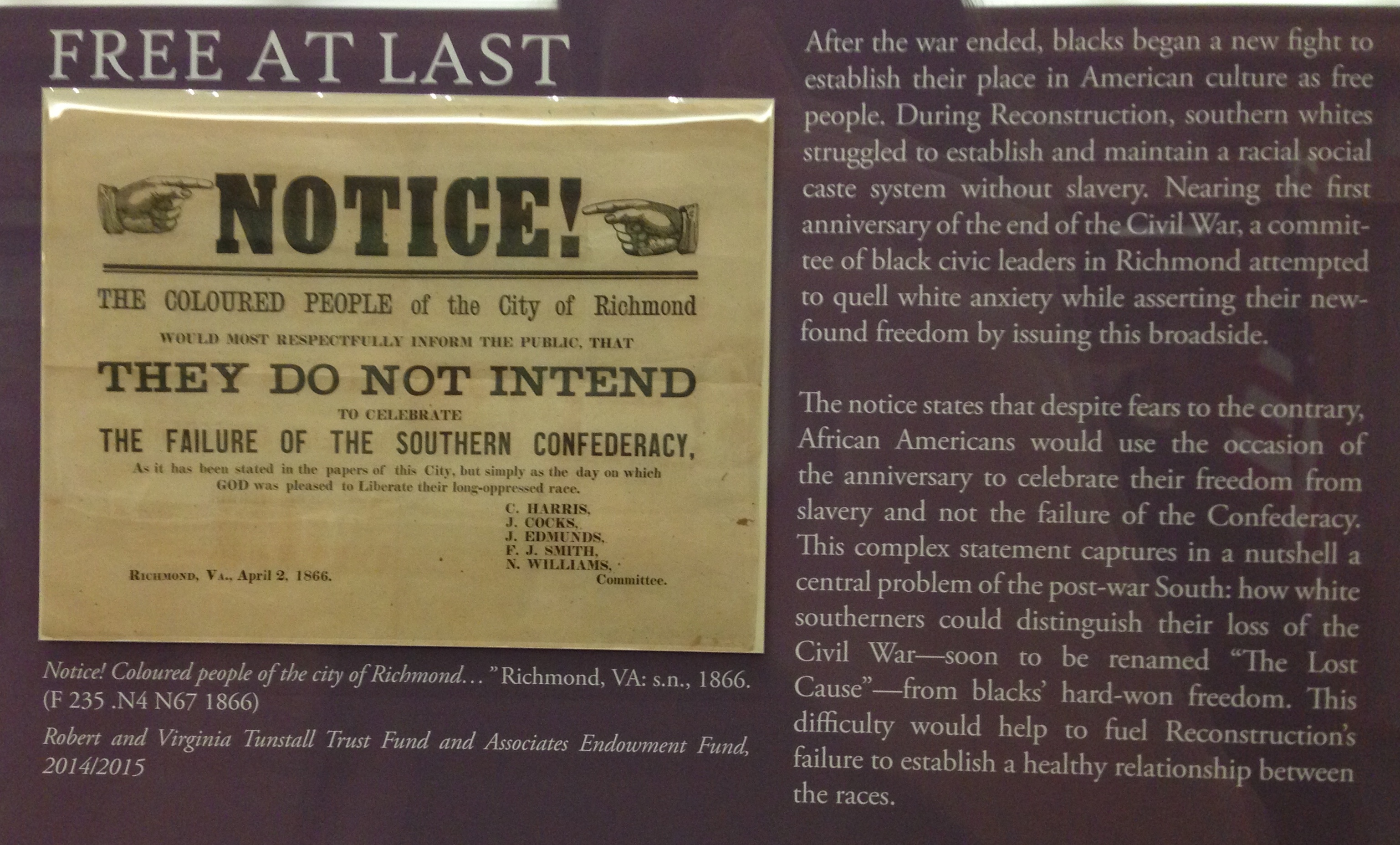

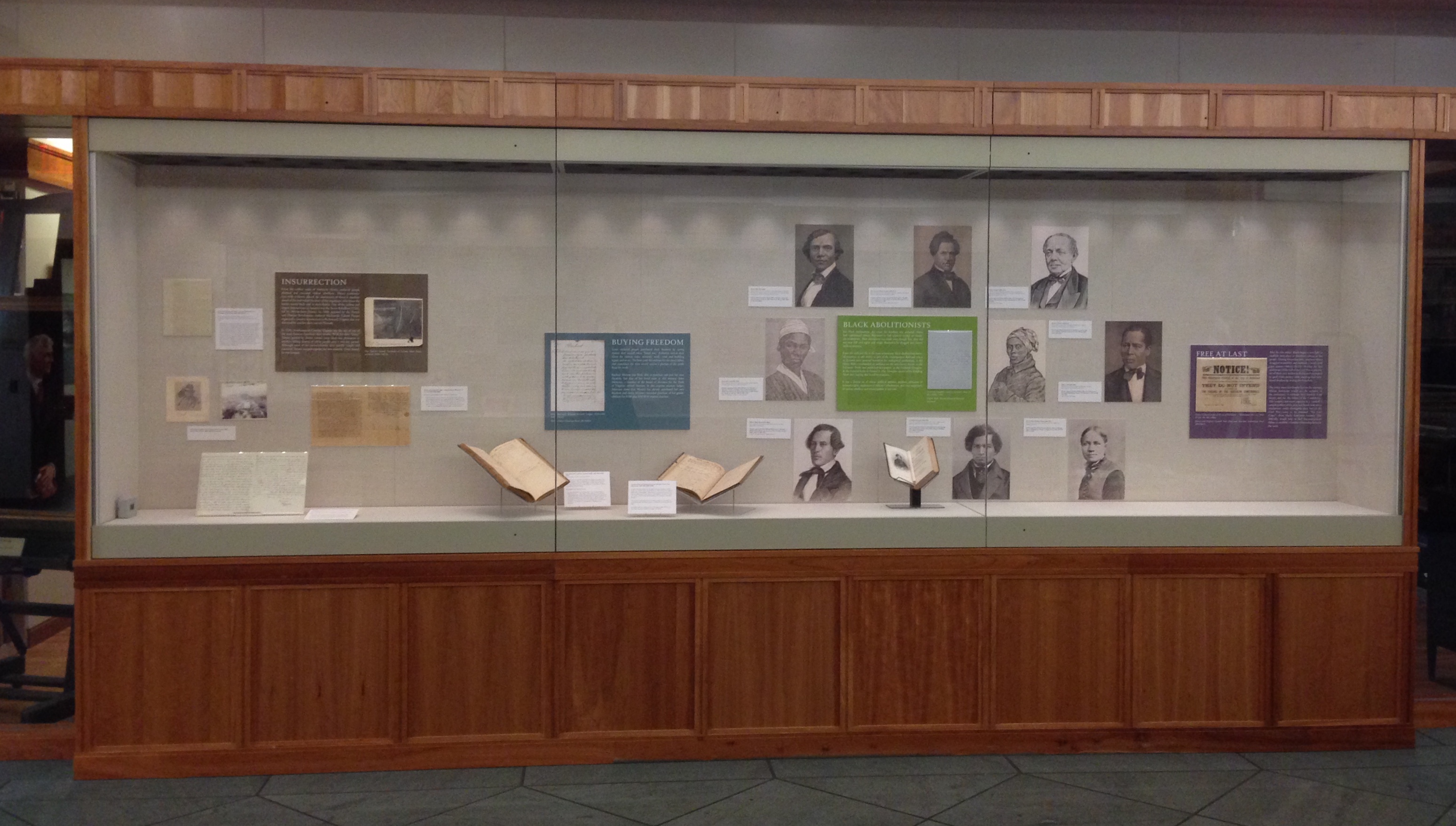

The exhibition displays artifacts that document a variety of forms of rebellion: running away, planning insurrections, writing abolitionist works and manifestoes, and buying one’s own and one’s family’s freedom. It concludes with a recently acquired broadside printed by African-American leaders in Richmond a year after the city surrendered.

The exhibition displays artifacts that document a variety of forms of rebellion: running away, planning insurrections, writing abolitionist works and manifestoes, and buying one’s own and one’s family’s freedom. It concludes with a recently acquired broadside printed by African-American leaders in Richmond a year after the city surrendered.

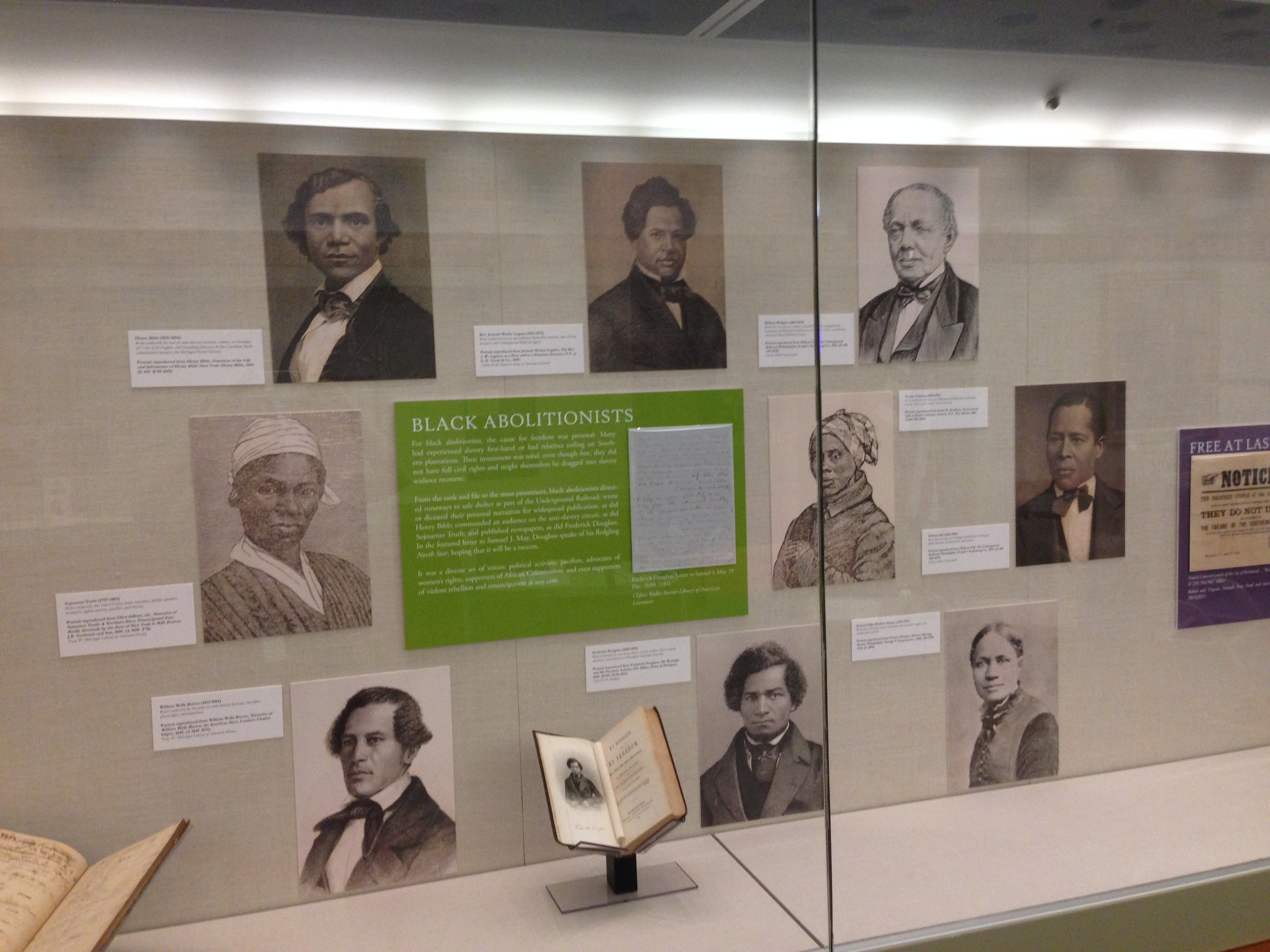

Portraits of black abolitionists from books in our collections are featured in the gallery and on the poster.

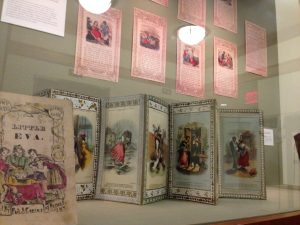

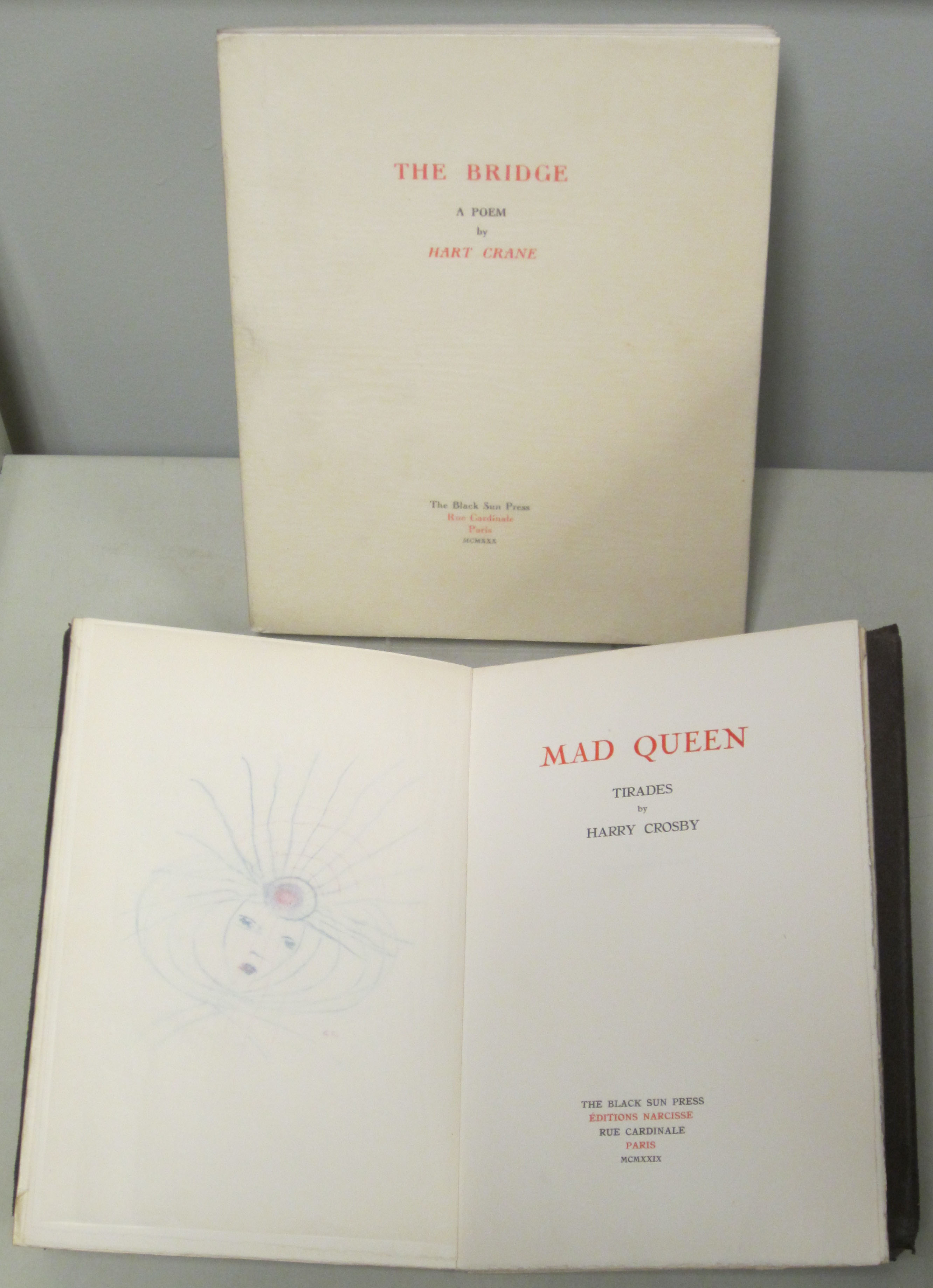

Our mini-exhibition, “Read, Weep, and Reflect: Creating Young Abolitionists through Uncle Tom’s Cabin” was curated by undergraduate Wolfe Docent Susan Swicegood (CLAS 2015, Curry 2016). Curator Molly Schwartzburg asked Susan to develop an exhibition around a recently acquired early puzzle about Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel, which is our second such puzzle. Susan tracked down a wonderful range of children-related publications and “tie-in products” from the nineteenth century. It is not to be missed!