Welcome to our third installation of the ABCs of Special Collections! We give you the letter:

C is for Condensed French, which is one of 75 alphabets represented in Frank H. Atkinson’s Atkinson Sign Painting up to Now: A Complete Manual of Sign Painting. Chicago: Frederick J. Drake & Co., 1915 (not yet catalogued. Gift of Nicholas Curtis. Photograph by Caroline Newcomb).

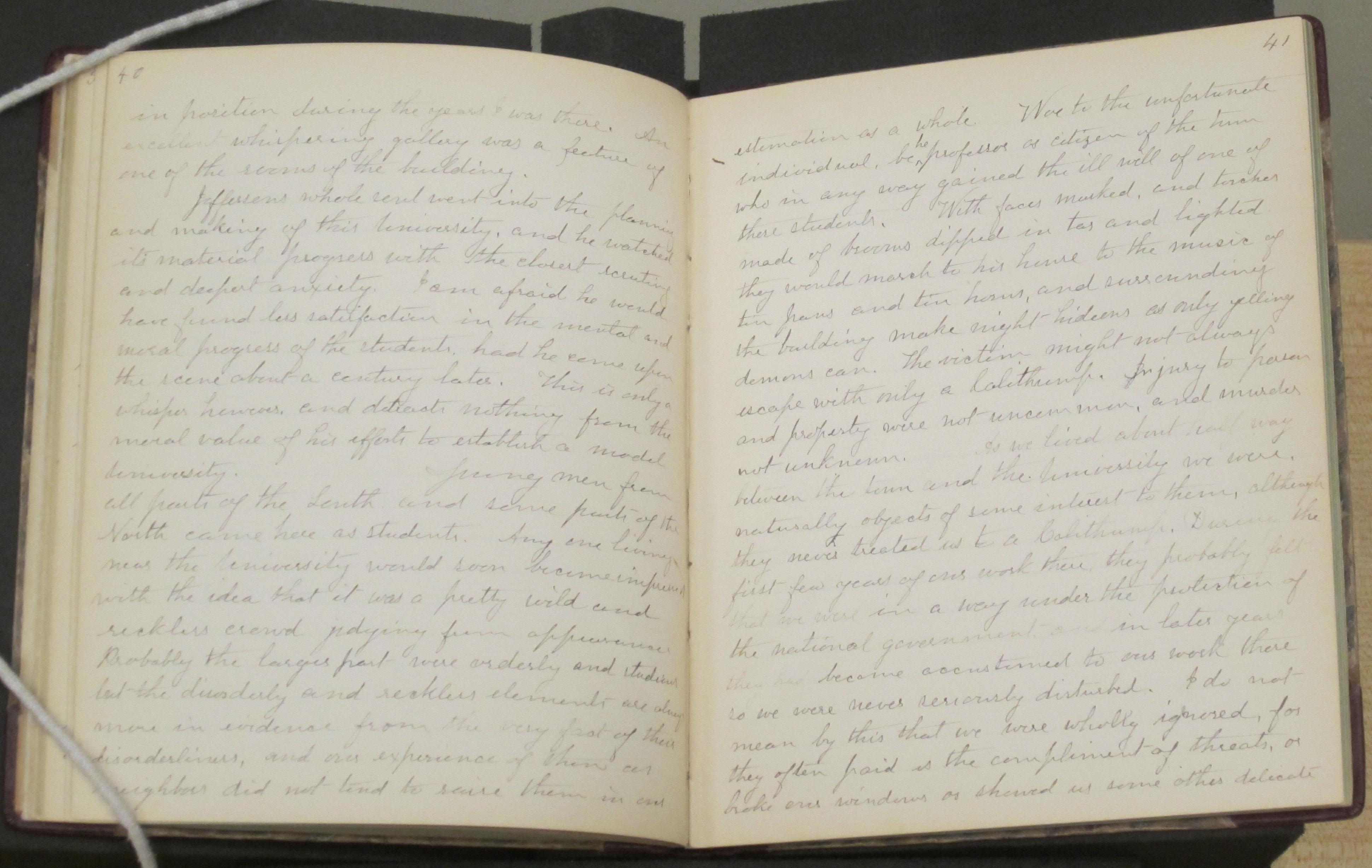

C is for “Calithump”

Webster’s defines “calithump” (variant spellings callithump and calathump) as a somewhat riotous parade, accompanied by the blowing of tin horns and other discordant noises.

Philena Carkin was a young schoolteacher from Massachusetts who came to Charlottesville, Virginia in 1866 as a representative of the American Freedmen’s Aid Commission to teach the newly freed slaves during Reconstruction. Her Reminiscences of my Life and Work among the Freedmen of Charlottesville, Virginia, from March 1st 1866 to July 1st 1875 (MSS 11123) is a no-nonsense description of Charlottesville, its inhabitants, the University of Virginia, and the surrounding area. In Chapter five she describes the “calithump” tradition among the University students:

Young men from all parts of the South and some parts of the North came here as students. Anyone living near the University would soon become impressed with the idea that it was a pretty wild and reckless crowd judging from appearances. Probably the larger part were orderly and studious but the disorderly and reckless elements are always more in evidence from the very fact of their disorderliness, and our experience of them as neighbors did not tend to raise them in our estimation as a whole. Woe to the unfortunate individual, be he professor or citizen of the town who in any way gained the ill will of one of these students. With faces masked, and torches made of brooms dipped in tar and lighted they would march to his house to the music of tin pans and tin horns, and surrounding the building make night hideous as only yelling demons can. The victim might not always escape with only a Calithump. Injury to person and property were not uncommon, and murder not unknown.

Contributed by Margaret Hrabe, Reference Coordinator

Carte de visite of Philena Carkin taken by William Roads. (MSS 11123. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

C is for Chinese Seals

Chinese seals are personal name stamps or signatures used on art, contracts, documents, etc. to signify authorship. Seals are created from a variety of materials, including stone, wood, and ivory. The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library holds well over 300 Chinese seals, representing individuals from the richest and most powerful (such as emperors) to the ordinary (such as merchants). John Maphis donated the collection in memory of his uncle, Charles Gilmore Maphis.

Contributed by Petrina Jackson, Head of Instruction and Outreach

Chinese Seals, 800 B.C. – 1800 A.D. (MSS 6678. Gift of John Alan Maphis. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Chinese Seals, 800 A.D. – 1800 A.D. (MSS 6678. Gift of John Alan Maphis. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

C is for Cotton

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a runaway best-seller, second only to the Bible in the number of copies sold in the nineteenth century. Stowe’s publisher commissioned John Greenleaf Whittier, a stalwart abolitionist, to write a poem about the character Little Eva and subsequently printed the words and music on a cotton handkerchief. This artifact of fervent capitalism shows just how deeply slavery was entrenched throughout American society: even the most zealous abolitionist message shamelessly profited from slave labor.

Contributed by Edward Gaynor, Head of Description and Specialist for Virginiana and University Archives

One score of Little Eva Song, printed on a cotton handkerchief. The words are by John G. Whittier, and the music is by Manuel Emilio. 1852. (Broadside .S68 Z99 1852c. Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

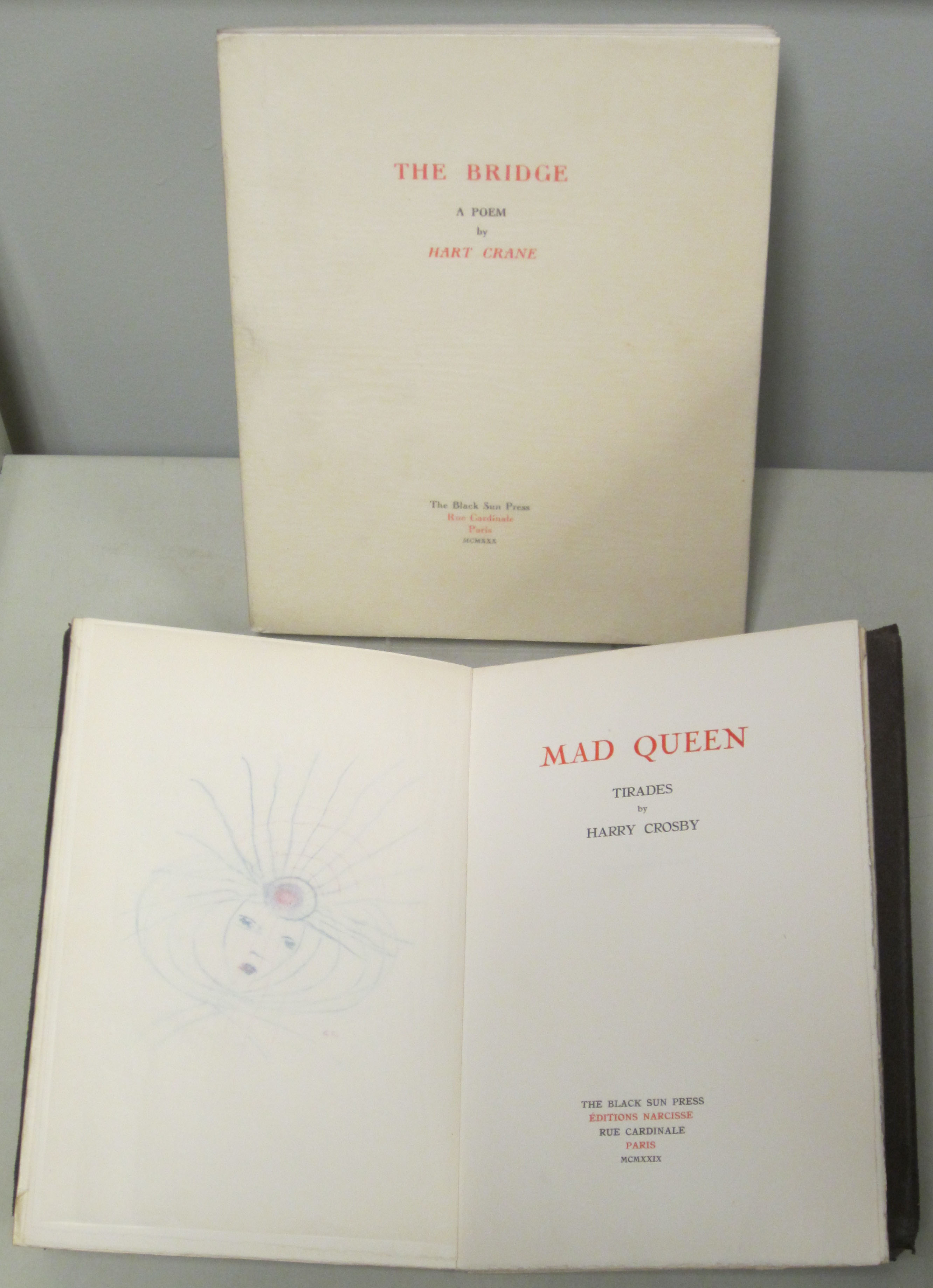

C is for Harry and Caresse Crosby

Perhaps no couple epitomized the Lost Generation in Paris of the twenties more than Harry and Caresse Crosby. Famously wealthy, the two hosted many social events for their artist friends, and pushed the limits of acceptable behavior to the delight of a scandalized public. In 1928 they founded The Black Sun Press in Paris. This highly influential small art press published, among others, James Joyce, Kay Boyle, Ernest Hemingway, Ezra Pound, Hart Crane, and William Faulkner, as well as editions of their own work. Caresse Crosby continued publishing after Harry’s dramatic suicide in 1929. Special Collections houses more than two dozen titles published by the press.

Contributed by George Riser, Collections and Instruction Assistant

Shown here is an edition of Hart Crane’s The Bridge, 1930, and Harry Crosby’s Mad Queen: Tirades, 1929. (PS 3505 .R272B7 1930b and PS 3505 .R883M3 1929 and, respectively. Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

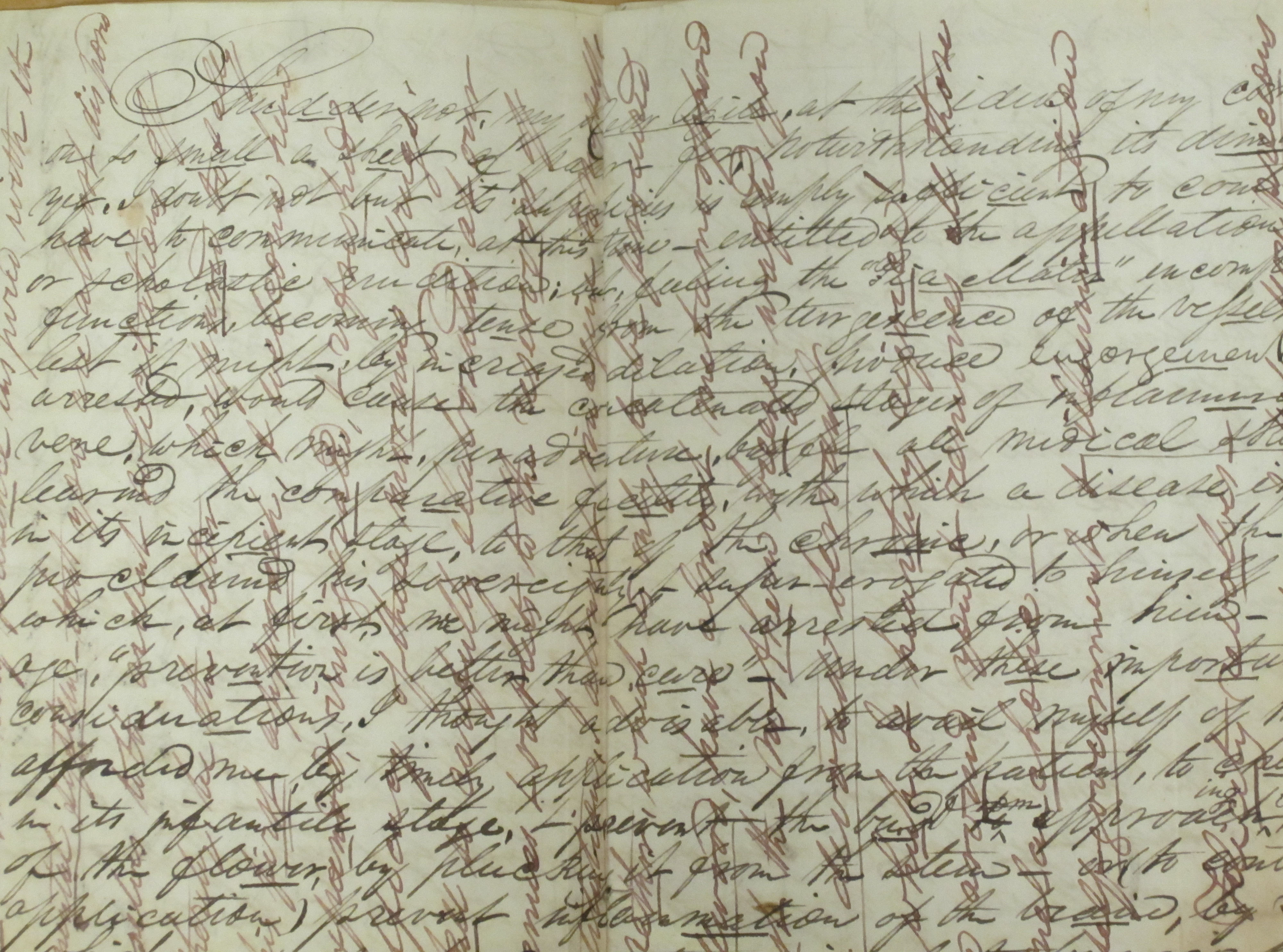

C is for Cross-Hatching (sometimes called cross writing)

Cross-hatching was a letter-writing practice popular in the nineteenth century. In a hand-written letter, the correspondent wrote across the paper in one direction and then turned the paper sideways to write across it at right angles to the original writing on the same page. This both conserved scarce paper and saved on postage costs.

C is also for cross, which is how an archivist trying to read cross-hatched letters feels at the end of the day.

C is also for cross-eyed; see above.

Contributed by Sharon Defibaugh, Manuscripts and Archives Processor

Cross-hatching used in a letter written by J. S. Wilson to Miss E. E. Richards, no date (MSS 5410. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Don’t forget to catch us next time when we cover the letter “D”!

Hello – I VERY much enjoyed this article on cross-hatching, which I found in a search because I was writing a poem about recycling scrap paper on which to compose, and I compared that thrifty habit to the cross-hatched writing of “olden days.”