This week’s post is contributed by two visiting undergraduate researchers, Megan Flanery and Hunter Walsh, who traveled all the way from Southern Georgia University to examine our Breece D’J Pancake manuscript collection. They represent a growing demographic of Special Collections researchers, and one that we value deeply here at UVA: undergraduates with an understanding of the importance and value of archival research. Thank you, Megan and Hunter, for sharing your experience with us here on the blog!

Megan:

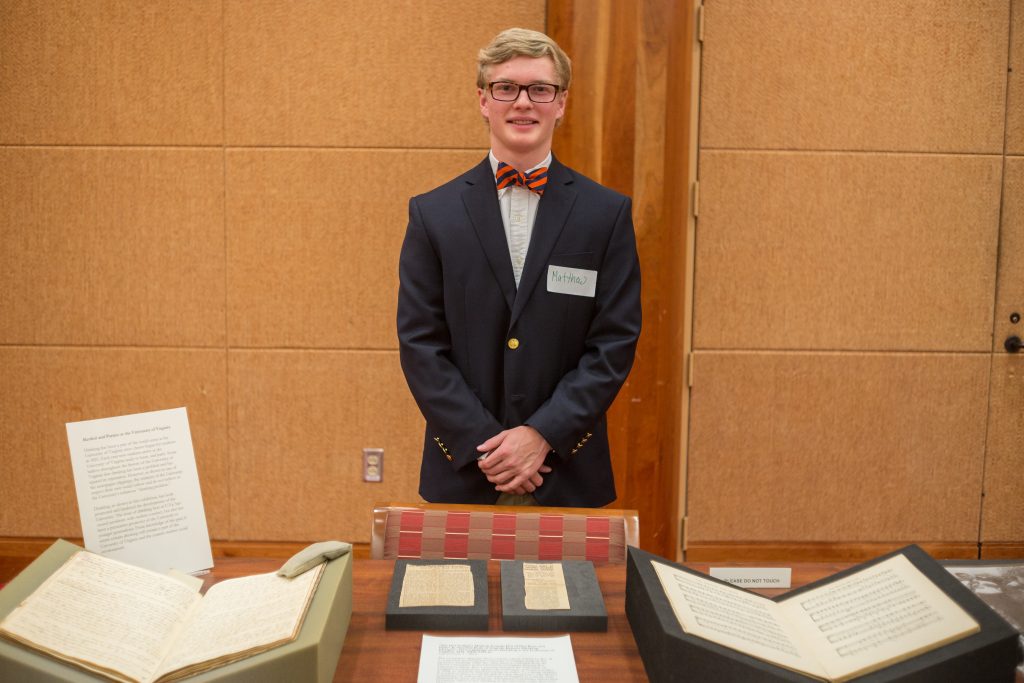

My colleague, Hunter Walsh, and I are both fourth-year undergraduate students at Georgia Southern University, and we will be graduating in the fall of this year. We were first introduced to Breece Pancake’s short story collection in 2014, when we studied his text under the direction of Dr. Olivia Carr Edenfield during her course on the American short story. Although we approach Pancake’s fiction from very different angles, both Mr. Walsh and I will present our undergraduate capstone projects on Pancake’s work. Our archival work at The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library has broadened our understanding of Pancake’s short, yet accomplished life. Our ultimate goal is to shed light on Breece Pancake, an under-appreciated Appalachian author, and we hope to bring new perspectives to the limited critical conversation that surrounds his fiction.

Originally from Michigan but now a Georgia resident, Megan Flanery is 21 years old and currently a senior at Georgia Southern University. Here, she will earn a BA in English with a minor in Philosophy, and she plans to continue her studies by attending graduate school at East Carolina University. The focus of her scholarship is American literature, particularly that of the twentieth century. She enjoys reading the works of authors such as Sherwood Anderson, Ernest Hemingway, J.D. Salinger, Eudora Welty, Raymond Carver, Cormac McCarthy and, especially, Breece Pancake.

Hunter:

Megan and I uncovered a countless amount of material. We found family photographs, postcards, interviews, and even personal letters from and to Breece Pancake. For me, these are all extremely interesting artifacts and sources that have really molded my study of Pancake’s work. The material I recovered has shed new light on his personal life and his relationships. Since I am interested in the family unit in Breece Pancake’s short fiction, this research has really opened up my reading. Breece’s biographical accounts of his life and his own admission to incorporating true elements into his writing offered even more insight into the familial relations in his writing. This was my first time doing archival research and I cannot thank the University of Virginia and Professor John Casey enough for allowing me this opportunity. The staff at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library were friendly and a tremendous support as well.

Hunter Walsh is an English major and Writing minor. He hails from Bristol, Virginia and is recipient of the 2015 Powell Award for Fiction Writing. His paper, “The Family in the Life and Works of Breece D’J Pancake,” examines the life and writings of Breece D’J Pancake. It documents Pancake’s personal experience with family and isolation, while highlighting these themes, via his experiences and perceptions, in his short fiction.

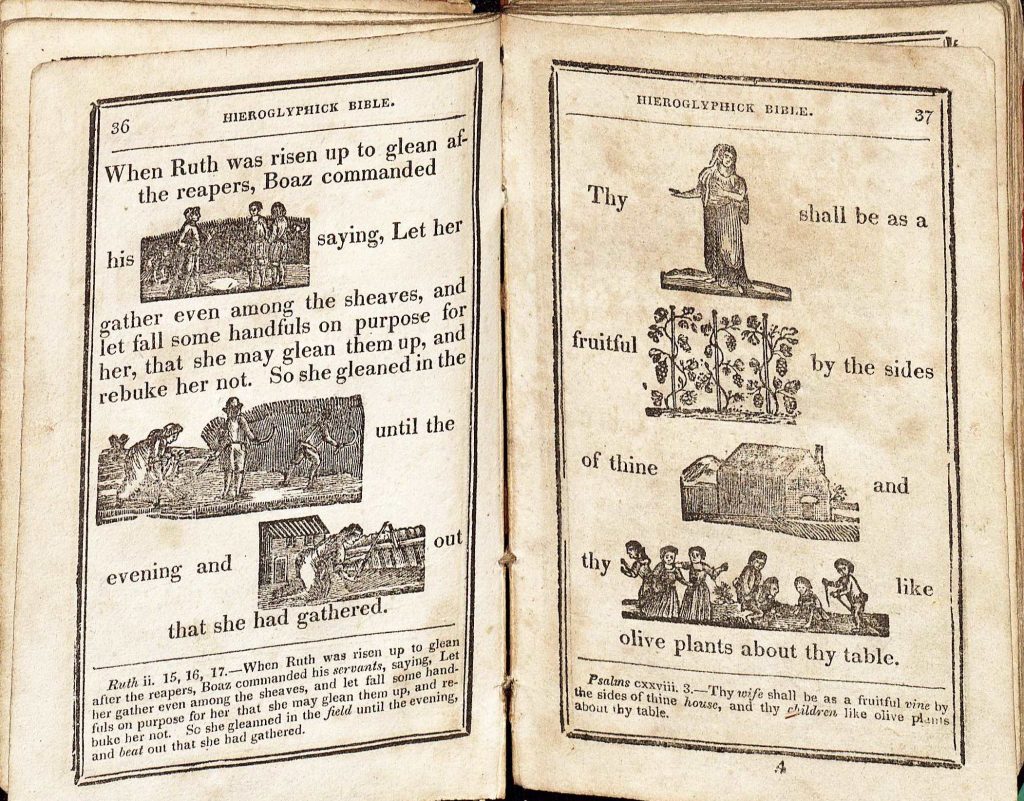

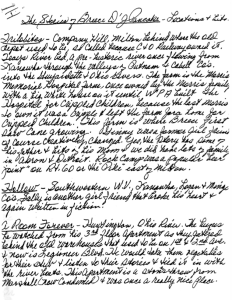

One of the most useful documents we unearthed is a catalog of the real sites and locations that have been included in Pancake’s work, written by his mother, Helen Frazier Pancake:

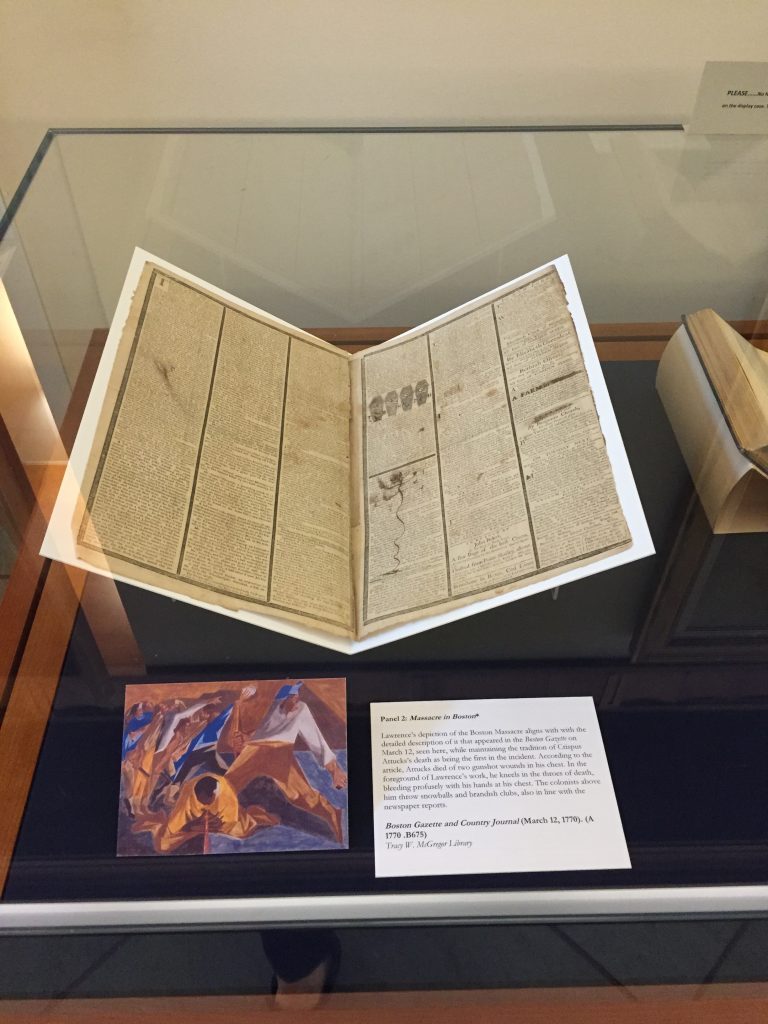

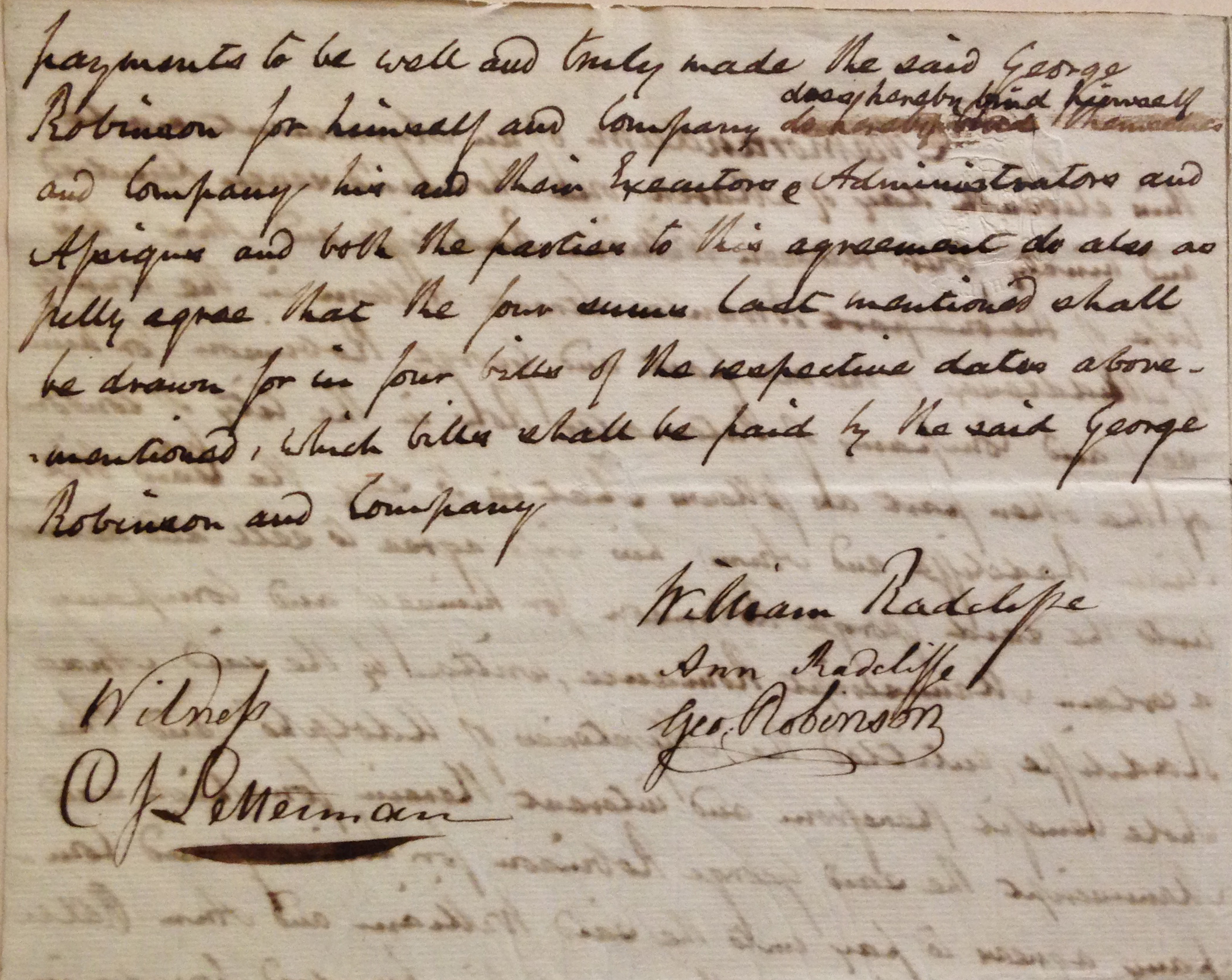

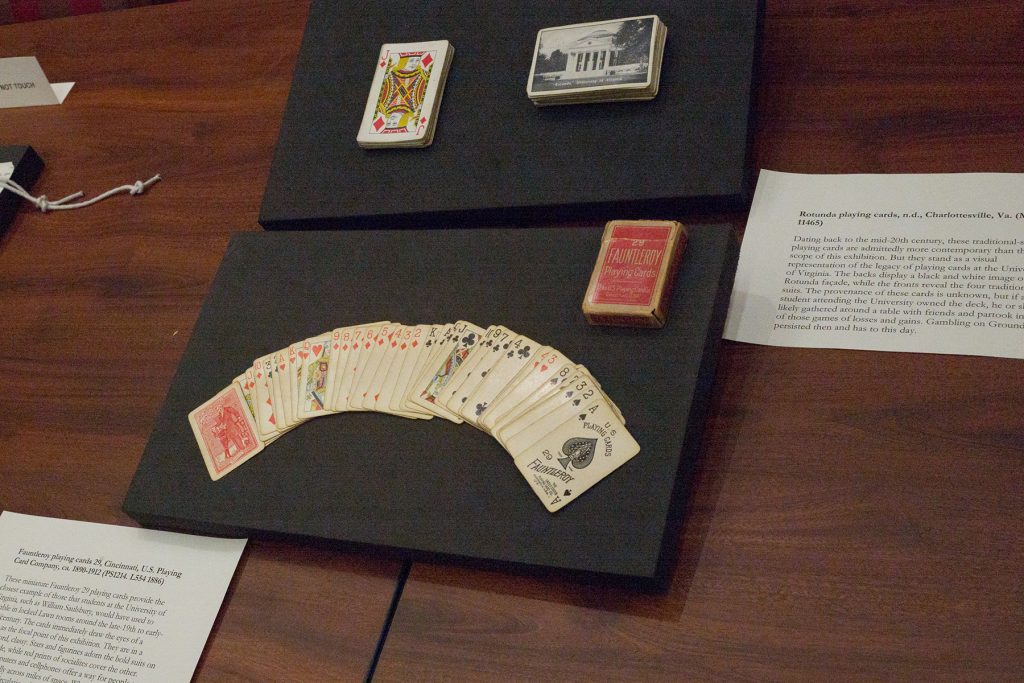

“The Stories of Breece D’J Pancake – Locations and Sites,” written by Helen Pancake, Breece’s mother. The various sites, with which Pancake was well-acquainted, reveal how Pancake weaved his own memories into his fiction. (MSS 10975-e 1.5)

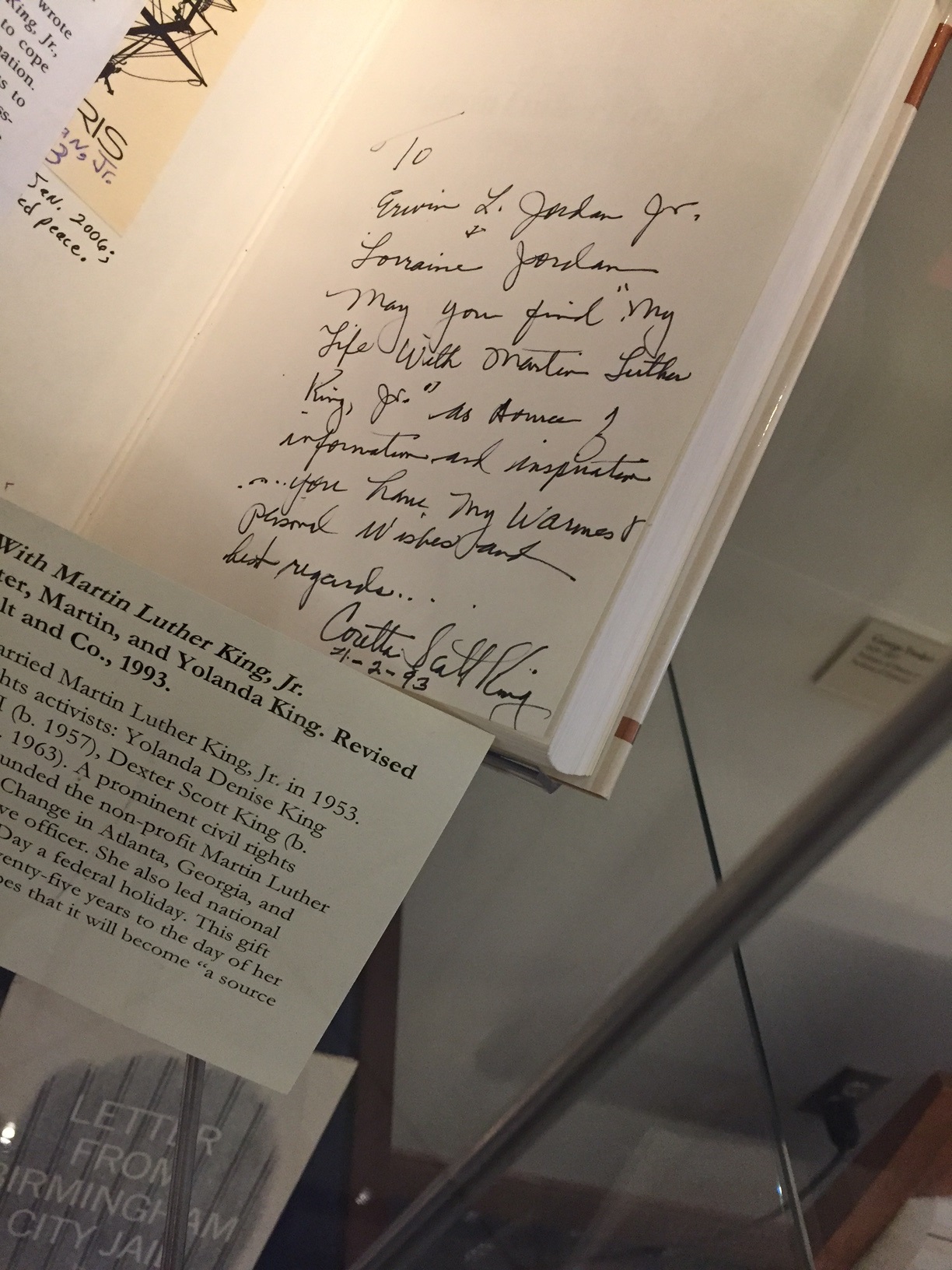

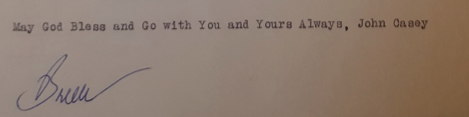

My thesis is centered on memory and the negative effects of rumination and obsessive nostalgia; therefore, my research on Pancake’s own life has been crucial to understanding the ways in which memories affected him. His last letter, written to his major professor, Dr. John Casey, is filled with memories that Pancake was fixated upon:

Box 1 of MSS10975-a, folder 5, holds Breece Pancake’s last piece of correspondence. Shown here is the signature line, where he thanks the recipient, UVA’s Henry Hoynes Professor of Creative Writing John Casey. In the body of tje letter, he lists the various dates of the significant, yet traumatic, events that weighed on him. Two weeks after this letter was composed, Breece took his own life.

Megan:

Although our study of Pancake’s life was dejecting at times, it allowed us both to appreciate Breece Pancake as a person, and not just as a writer. For now, our findings will be applied to some aspects of his fiction to highlight Pancake’s vexing themes; however, I plan to use this wealth of information to compose eventually a book-length study of Pancake’s life and works.