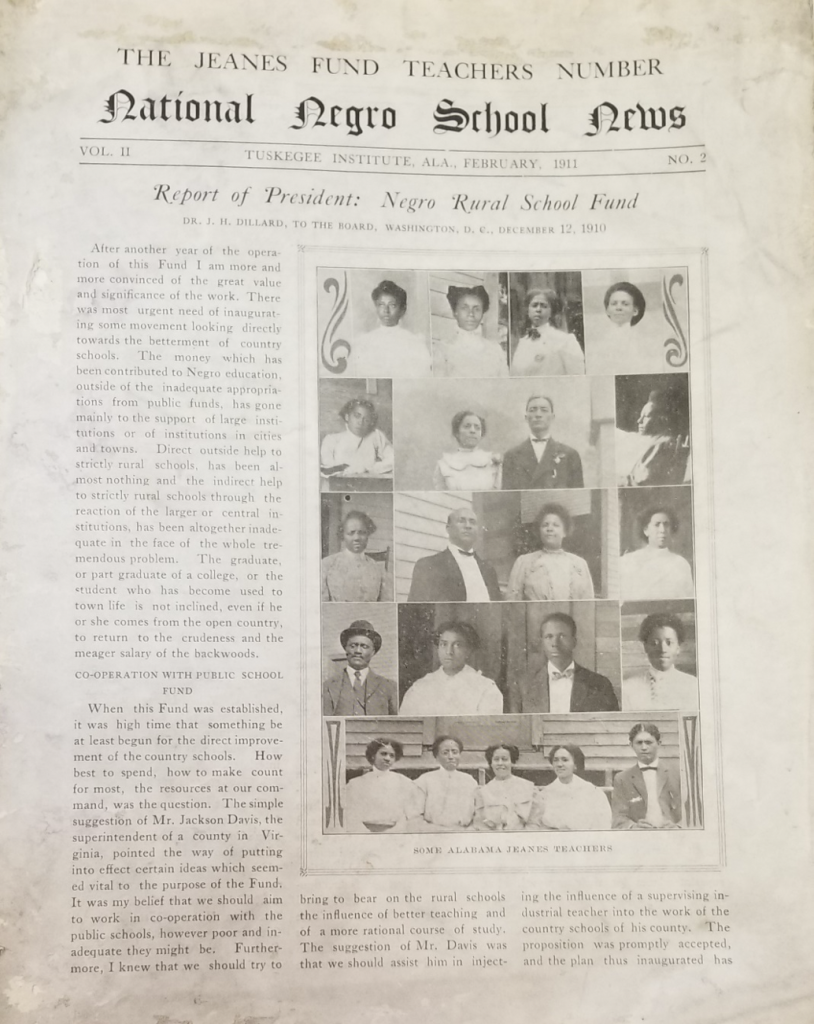

We are very excited to share some photographs of the 1981-1982 Virginia Cavaliers Men’s basketball team transferred from the University’s Athletic department and now housed in our Small Special Collections Library. This blog post was contributed by Ellen Welch (Manuscripts and Archives Processor at the Small Special Collections Library) and her husband, Peter Welch (University of Virginia Library Information Technology Department). Both Ellen and Peter are longtime fans of UVA basketball and have attended games since the 1970s!

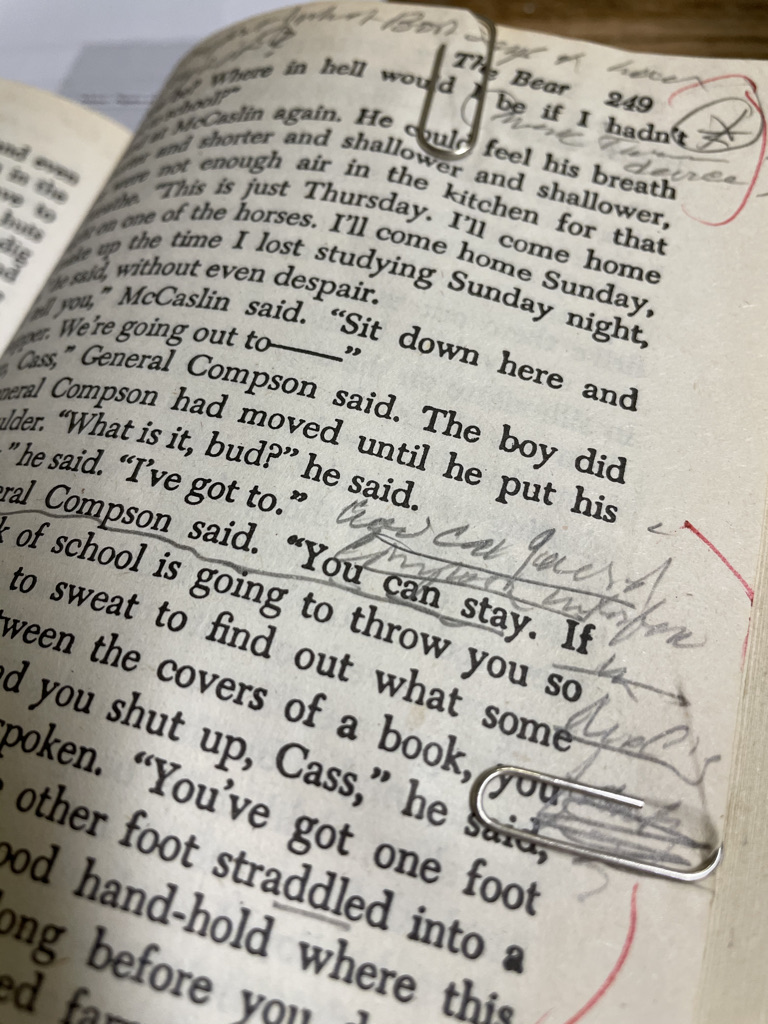

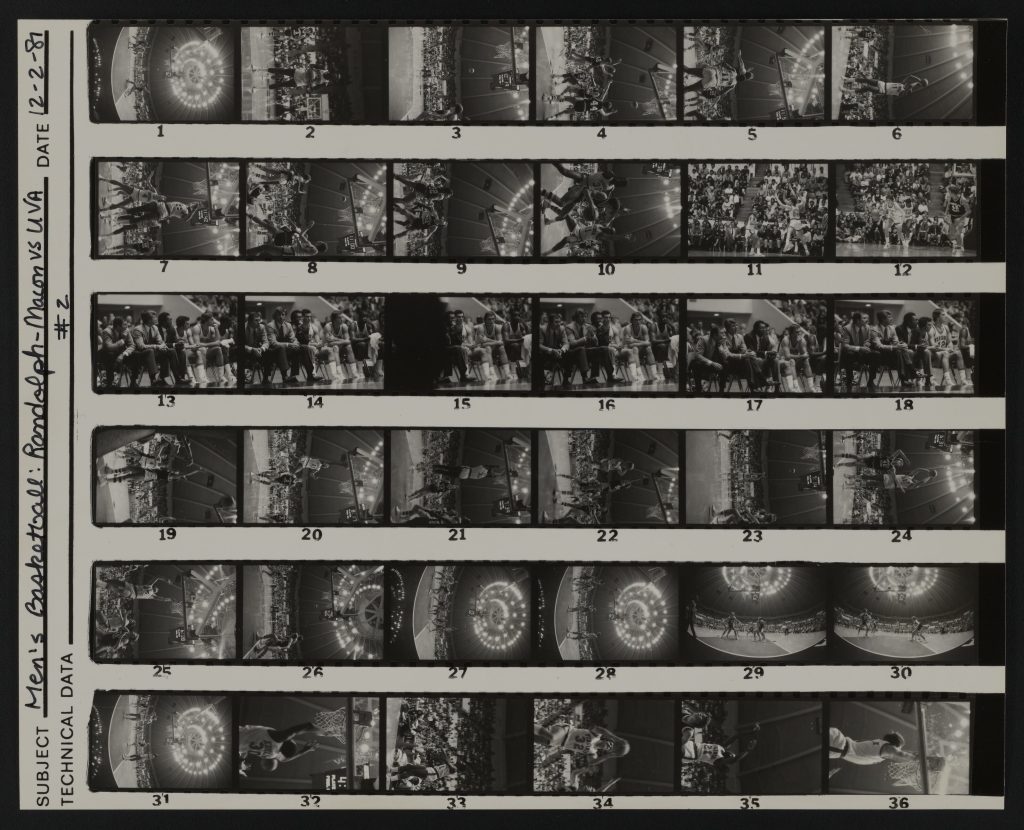

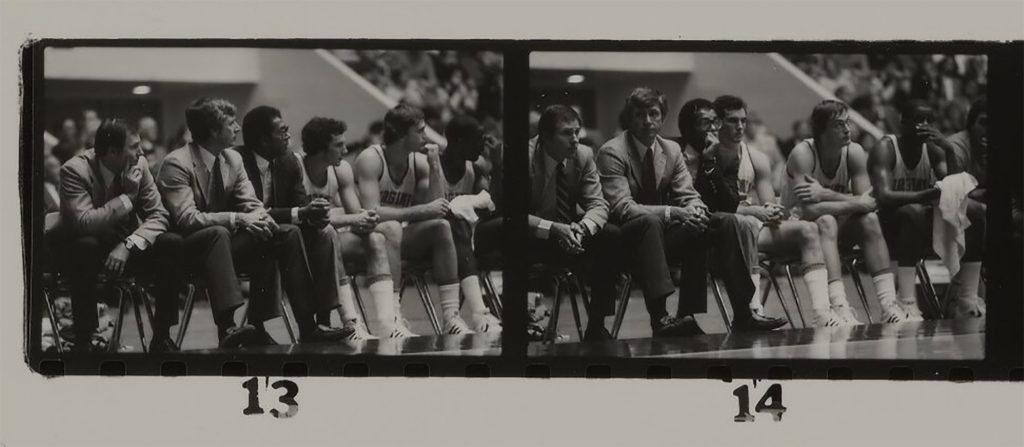

A contact sheet of photographs from the December 2, 1981 UVA game against Randolph-Macon College in Ashland, Virginia. There are thousands of photographs of UVA sports, events, and life from 1965 – 1973 in the photographic files of University photographer Dave Skinner / University of Virginia Printing Services Photograph File and Index (RG-5/7/2.762).

The 1981–82 University of Virginia Cavaliers Men’s basketball team—members of the Division 1 ACC (Atlantic Coast Conference)—held the top seed in the Mideast Region of the 48-team NCAA Tournament (National Collegiate Athletic Association) and made it to the Sweet Sixteen until they were upset by just two points, losing to the University of Alabama-Birmingham (UAB). The Mideast bracket followed with UAB losing to Louisville 75-68 and Georgetown beating Louisville 50-46. In the finals of the tournament, Georgetown lost 63-62 against UVA’s longtime rival, Dean Smith’s University of North Carolina Tar Heels. Many basketball players who later rose to national prominence were introduced that year, including UVA’s Ralph Sampson, who played for the University from 1979-1983 before going professional in the National Basketball Association (NBA); North Carolina Tar Heel and Los Angeles Laker James Worthy (“Big Game James”); Sam Perkins; and one of the greatest athletes of all time, Michael Jordan.

In the 1981-82 NCAA tournament, Curry Kirkpatrick’s article “Sweet 16 and the 32 Who Missed” describes Virginia’s win over Tennessee to get into the round of sixteen:

…Give the Cavaliers a D—D for the desire of Othell Wilson, who played on one leg and with one painful thigh bruise, and D for the determination of Ricky Stokes, who drilled the two winning free throws in Virginia’s 54-51 escape in Indianapolis from the mechanical clutches of Tennessee. Oh yes, and add another D for Ralph Sampson’s defense on Dale Ellis, who shot up the Cavaliers until Sampson shut him down. Jeff Jones suggested the move in the huddle and what it did was disrupt the Tennessee tempo—”He made Dale pull the string,” said Vol Coach Don DeVoe—wipe out a 10-point deficit and give control of the game to the Cavs. …Four straight Sampson buckets, a 51-51 tie and shortly a Virginia freeze. Stokes got a high-five from Wilson just before he went to the line for his crucial free throws.

Ricky Stokes (who clocked in at a height of 5’ 10) said, “Ralph and I have the same initials, I can use his monogrammed handkerchiefs, but not his shirts.” Ralph Sampson was the tallest player on the team (7′ 4).

The 1981-82 team had several freshman recruits—including Jimmy Miller, Tim Mullen, Dan Merrifield, and Kenny Johnson—because Jeff Lamp, Lee Raker, and Terry Gates had graduated. Mullen and Miller were solid role players for the next four years. The surprise player that season was walk-on Kenton Edelin (#30) who played good defense off the bench as a backup forward and center behind basketball star Sampson. Edelin went on to be a good role player the next two years and eventually played in the NBA. Jeff Jones was the starting point guard with Ricky Stokes backing him up and Othell Wilson was the other starting guard. They all played good defense and good team basketball. Tim Mullen started every game that year as a freshman. Craig Robinson was the other starter at forward. They won 30 games but had a disappointing loss in the NCAA tournament to UAB in the 2nd round. They had to play UAB on their home court at Birmingham so that didn’t help. Ralph Sampson averaged 15 points per game that season, which is high scoring, but only taps the potential for a guy who could dominate the game. He scored up to 30 points when he played in the NBA. Sampson declared for the NBA draft after the 1981-1982 season but ultimately decided to return for one more season with the Cavaliers. His final season was the last before the institution of the shot clock rule which kept teams from unfairly holding the ball until the last second of the game. The 3-point shot was also introduced that year in ACC games. The next year—their first year after Sampson had graduated—UVA made it to the Final Four. Go figure? Great things were to come for the Virginia Cavaliers, particularly winning the NCAA tournament in 2019 under coach Tony Bennett.

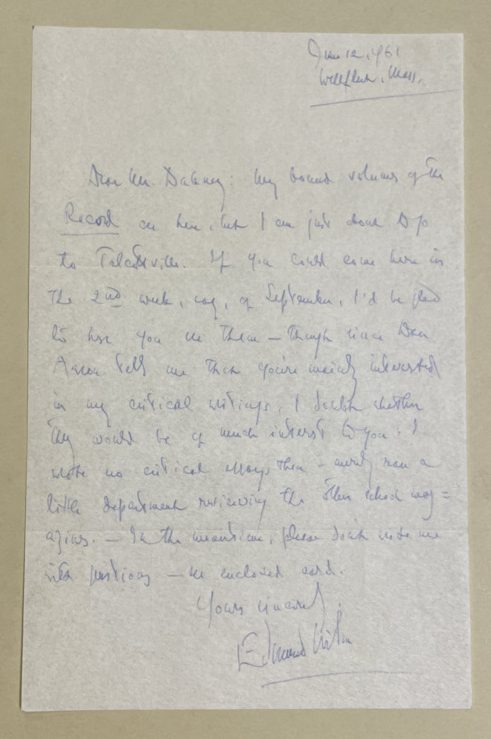

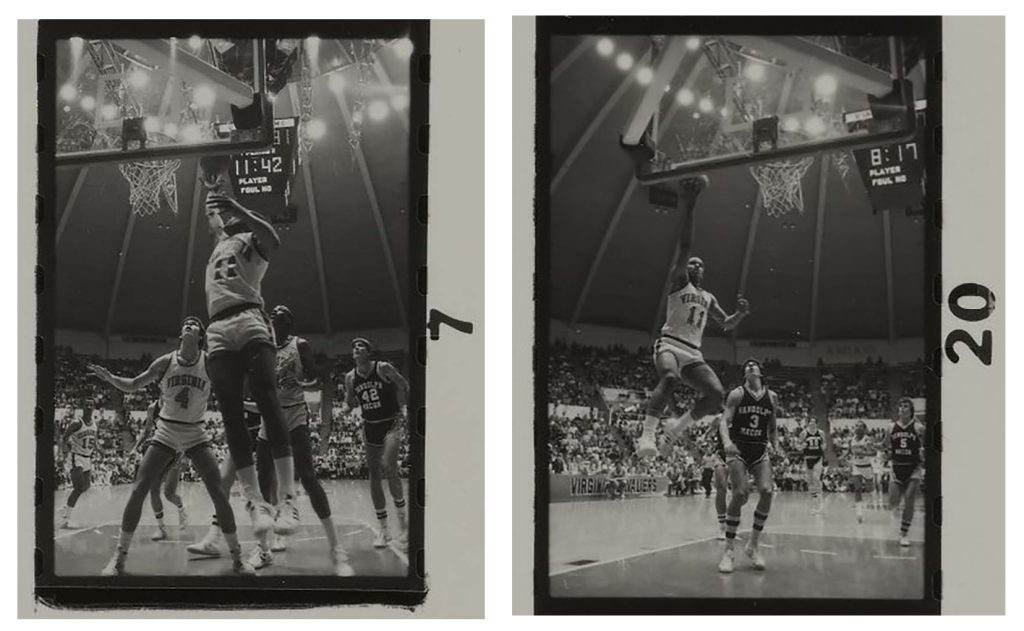

Left: Othell Wilson (#11) goes for a dunk with freshman forward Jim Miller(#4) assisting on the shot. Right: Wilson makes another shot. Two points! From the University of Virginia Printing Services Photograph File and Index (RG-5/7/2.762).

Shown here are scenes from a regular season game on December 2, 1981 where the UVA Wahoos (formally called the Cavaliers, but familiarly called the “Wahoos” or “Hoos”) defeated Randolph-Macon in Ashland, Virginia 82-50. The Cavaliers were coached by Terry Holland with assistant coaches Craig Littlepage and Jim Larranaga. It was star player Ralph Sampson’s sophomore year although he was not in the lineup for this game. High scorers of the 1981-82 season were Ralph Sampson (15.8 points per game), Othell Wilson (11.4), Craig Robinson (9.7), and Jeff Jones (8.2). Jeff Jones was a prolific passer and had 598 assists.

The team members consisted of:

- Number 4 Jim Miller, forward 6’8 Freshman

- Number 10 Craig Robinson, forward 6’8 Junior

- Number 11 Othell Wilson, guard 6’0 Sophomore

- Number 12 Dean Carpenter, forward/center 6’9 Senior

- Number 14 Ricky Stokes, guard 5’10 Sophomore

- Number 21 Jim Runcie, guard 6’1 Freshman

- Number 24 Jeff Jones, point guard and team captain 6’4 Senior

- Number 30 Kenton Edelin, forward 6’7 Sophomore

- Number 32 Doug Newburg, guard 6’2 Junior

- Number 33 Kenny Johnson, guard 6’0 Freshman

- Number 42 Peter MacBeth, forward 6’9 Junior

- Number 45 Tim Mullen, guard, forward 6’5 Freshman

- Number 51 Dan Merrifield, forward 6’6 Freshman

- Number 55 Ralph Sampson, center 7’4 Junior

UVA Basketball History:

Henry “Pop” Lannigan started the University of Virginia basketball program in 1905 and had a successful season until his death in 1930. He accumulated a dominant overall record of 254–95 (.728 winning percentage) over twenty-four seasons as the UVA head coach.

Gustave “Gus” Kenneth Tebell was the coach from 1930 to 1951, achieving his first championship in just his second year. During his tenure, he compiled a 240–190 record, including a National Invitation Tournament berth in 1941.

After a series of coaches with more losses than wins, the Cavalier regained success under Terry Holland who began coaching in 1974. He had a winning record of 326–173. His tenure at Virginia (through 1990) also included 1981 and 1984 Final Four appearances, a 1980 National Invitation Tournament championship, Virginia’s first of three ACC Tournament championships (1976), and two ACC Coach of the Year awards. In addition to all-star Ralph Sampson, there were many great basketball players during Coach Holland’s career, including brothers Ricky and Bobby Stokes, Barry Parkhill, Marc Iaveroni, Lee Raker, John Crotty, Wally Walker, Jeff Lamp, and many others.

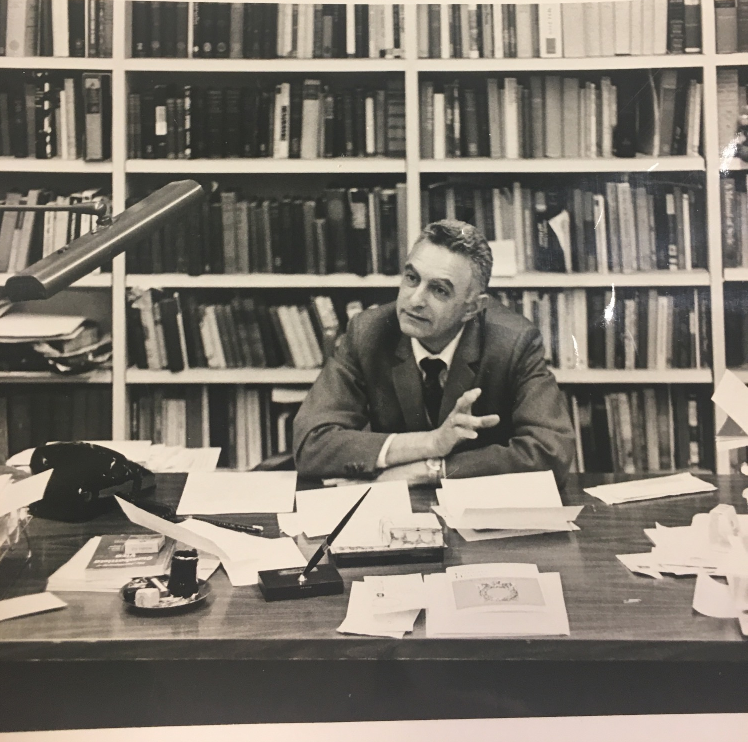

Coach Terry Holland (second to the left) with the Virginia Cavaliers coaching staff at the Randolph-Macon College game, December 2, 1981.

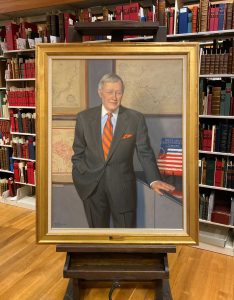

Coach Tony Bennett became head basketball coach at UVA in 2009 and led the Cavaliers to their first NCAA Tournament Championship in 2019. Bennett came to Charlottesville after spending the previous three seasons as the head coach at Washington State, where he was the 2007 National Coach of the Year. Bennett was named one of the 2011 Summit League’s (formerly the Mid-Continent Conference) Top 30 Distinguished Contributors for the league’s first 30 years at the Division I level. In January of 2016, Bennett was part of the Summitt League’s inaugural Hall of Fame class. Bennett is a three-time recipient of the Henry Iba Award, two-time Naismith College Coach of the Year, two-time AP Coach of the Year, and four-time ACC Coach of the Year. He was named to a list of the World’s 50 Greatest Leaders by Fortune magazine. By 2019, Bennett was a three-time National Coach of the Year. This year, he enters his 13th year as the Dean and Markel Families Men’s Head Basketball Coach at the University of Virginia. As of the 2021-22 season, Virginia has had ten consecutive winning conference seasons, the longest active streak among ACC programs.

Tony Bennett, Dean and Markel Families Men’s Basketball Head Coach. (Photo by Matt Riley, UVA Athletics)

Tonight—November 9, 2021— the Virginia Cavaliers Men’s basketball team opens their season with a game against Navy at John Paul Jones Arena. We hope to see you there!

Sources:

“Ala-Birmingham, Louisville get by Sampson, Breuer” Reading Eagle. (Pennsylvania). Associated Press. March 19, 1982. p. 24.

1981–82 Virginia Cavaliers men’s basketball team, Wikipedia. Retrieved 9/27/2021.

Martin, Steve, “UAB Blazers slay giant Virginia”. Tuscaloosa News. (Alabama). March 19, 1982. p. 12.

Wilson, Austin, “UAB stuns Virginia with 68-66 triumph”. Free Lance-Star. Fredericksburg, Virginia. Associated Press. March 19, 1982, p. 10

Jeff Jones Basketball, Wikipedia. Retrieved 9/28/2021.

Wysong, David, “The Game Michael Jordan Changed Everyone’s Perception of Him” Tweet and Facebook, March 29, 2020

Teel, David, “Victory over UNC elevates UVA’s Bennett into rare company“. Richmond Times-Dispatch, February 13, 2021. Note that the article mentions it was the second-longest at the time, before Duke failed to achieve a winning record in that season

Tony Bennett, Dean and Markel Families Men’s Head Basketball Coach. Virginia Sports.

Payne, Terrence, “Tony Bennett signs a seven-year deal with Virginia.” NBC Sports Jun 3, 2014.