This post was contributed by Ellen Welch, Manuscripts and Archives Processor with reparative comments from Whitney Buccicone, Director of Technical Services and edits by Katie Rojas, Archival Processing and Discovery Supervisor, all staff of the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

Note: Many years ago, the Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia Library was fortunate to receive the papers of Senator Carter Glass, a Virginia politician for fifty years with international and presidential influence. His papers were recently reprocessed so that banking legislation could be kept together in one series and legislation and political content could be separated, allowing researchers to identify these parts of the collection more easily (revised finding aid now available). It is a large collection of 283 document boxes containing his original correspondence, legislative drafts, printed bills, newspaper clippings, and speeches. In reprocessing the collection, it has been fascinating to gain a glimpse of some of the major events in the nineteenth and twentieth century history through his eyes. This was sometimes daunting and illuminating at the same time.

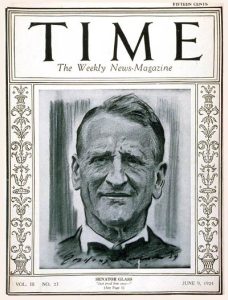

Carter Glass (January 4, 1858 – May 28, 1946) was born in Lynchburg, Virginia to Robert Henry Glass and Augusta Elizabeth Christian. He became one of the longest serving politicians of his time—Senator of Virginia from 1920 to 1946, nominee for President of the United States in 1924—and successfully drafted and oversaw passage of some of the hardest fought and heroic banking legislation in history: the Federal Reserve Act (1913) and the Glass-Steagall Act (1932). However, he also helped to create the racist 1902 Virginia Constitution that disenfranchised the Black vote in Virginia.

Childhood

Carter Glass was a small but raucous country boy. Older boys in the neighborhood thought that they could pick on him because of his size, but he would fight them off with stones—they quickly learned to leave him alone. He earned the life-long nickname of Pluck because he refused to be bullied. Glass was a white child of privilege, and it was during this time that the foundation of Glass’s racism was built and was further cemented when his childhood was suddenly cut short by the outbreak of the Civil War. He had to quit school and apprentice at his father’s newspaper to help his family. The Civil War and Reconstruction period had a profound effect on Glass, shaping his early political views based on his memories that outsiders and African Americans were taking over the state of Virginia and responsible for its impoverished conditions. In typical Glass verbiage, the young boy claimed he was going to grow up and shoot “dadgum” Yankees.

Newspaper Career

From a young age, Carter Glass wanted to become a reporter for his father’s newspaper. At age thirteen, he apprenticed for the newspaper and read books from his father’s library to augment his formal education. Glass had an impressive vocabulary which he used to his advantage throughout his career. Father and son shared the same political thinking but worked at different newspapers, often sparring with each other on specific issues much to the entertainment of the local Lynchburg public. One day his father stormed into his son’s office after reading an offensive article in the newspaper, saying “Where did you get that?” Young Glass responded that he kept a scrapbook. “You wrote that about three years ago.” His father turned and stomped out of the office, snorting as he went, “I have no respect for a person who keeps a scrapbook.”

Political Career

Following his success in the newspaper business, Carter Glass turned his attentions to politics. After hearing a speech by William Jennings Bryan in 1896, he was moved by Bryan’s oration and felt called to enter politics as a delegate in the 1901-1902 Virginia Constitutional Convention. He was a strong supporter of fiscal conservatism and states’ rights. A Southern Democrat, a Jeffersonian, and a supporter of segregation and Jim Crow laws, Glass served as a United States Senator from Lynchburg, Virginia starting in 1920 and was re-elected every term (running mostly unopposed) until his death in 1946. Many of his supporters have said that, at 5 foot 4 inches tall, his speeches and political prowess made him seem larger than life. Glass is described as having a ready wit, a combative personality, and a caustic tongue that spared no feelings—yet he was easily offended by any criticism of his positions, and often responded vindictively and meanly. Carter Glass thrived under the support of President Woodrow Wilson, but felt challenged under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He was opposed to many of Roosevelt’s policies and needed to balance his convictions with diplomacy to preserve his relationship with the President.

While Carter Glass is well-known for his banking reforms, it is not as well publicized that, as a member of the Virginia State Senate from 1899-1902, he led the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1901-1902 that produced the Virginia Constitution of 1902 and placed severe new restrictions on voter eligibility—specifically targeting African Americans voters. The Virginia Constitution of 1902 instituted a poll tax and a literacy test to determine voter eligibility.

When questioned as to whether these measures were potentially discriminatory, Glass exclaimed, “Discrimination! Why that is exactly what we propose. To remove every [African American] voter who can be gotten rid of, legally, without materially impairing the numerical strength of the white electorate.”

Indeed, the number of African Americans Virginians qualified to vote dropped from 147,000 to 21,000 immediately— and until the 1965 Voting Rights Act, discriminatory practices such as the poll tax and literacy tests continued in Virginia and other southern states.

Banking legislation

Glass was appointed Chairman of the House Committee on Banking and Currency in 1913. He played a major role in the establishment of the U.S. financial regulatory system, which was strongly supported by Woodrow Wilson. Their goal was to remove power from the bankers and place it in a separate agency to supervise the banks. His influence is reflected in the current structure of the Federal Reserve System today, which consists of twelve regional Reserve Banks and the Board of Governors in Washington, D. C.

Glass believed that the bankers kept finding ways around the banking legislation—and that this is what caused the stock market crash in 1929. After the crash, Glass-Steagall legislation focused on more bank regulation, separating investment banking firms and commercial banks and creating the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation).

His banking reforms earned him gratitude across the country, landing him on the cover of Time magazine twice, and many universities bestowed him with honorary degrees. Glass had a way of speaking out of one side of his mouth; after he successfully fought for the Federal Reserve Act, President Woodrow Wilson marveled at what Glass would be able to do using both sides of his mouth!

In 1918, President Wilson appointed Glass Secretary of the Treasury, where he marketed Victory Liberty Loans for World War I debts. He was also a representative for the peace talks after World War I and was determined to keep loans out of negotiations.

Photograph of Carter Glass with poster for Victory Loan program: “Bring Them Home.” (Library of Congress: Harris & Ewing Collection)

Glass had suffered from ill health throughout his life, and usually walked on tip toes because he believed that would help with his indigestion. He was often so ill that he travelled between the hospital and Capitol Hill to stay ahead of the fight on banking legislation. He died in his hotel apartment in Washington, D.C. on May 28, 1946. History remembers Carter Glass as the Father of the Federal Reserve Act, but today we also consider his role in the 1902 Virginia Constitution that disenfranchised every black voter in the state. Historian J. Douglas Smith cites him as “the architect of disenfranchisement in the Old Dominion.” In the late 1920s, Harvard University named their business school, Glass Hall, after his achievements in banking, but in 2020 they changed the name to Cash House for James Cash, the first African American tenured professor at Harvard.

Carter Glass was the one of the most influential politicians of his time, yet at the beginning of his young life, he noted, “after the fullest deliberation I have cheerfully concluded that I was not cut out for a politician.” At 88 years of age, he still refused to retire from the Senate even though he had not attended the Senate floor proceedings for years. At many points during his political career he claimed that he would have been happy to stay at home on his farm, buying his jersey cattle, and yet he never gave up his public service until death took it from him on May 28,1946.

For more information about Carter Glass:

- Guide to Carter Glass Papers at the Small Library at the University of Virginia Library: https://archivesspace.lib.virginia.edu/resources/206/edit#tree::archival_object_209477

- Mathew Fink talks about his book The Unlikely Reformer: Carter Glass and Financial Regulation: https://www.c-span.org/video/?468166-1/legacy-financial-reformer-senator-carter-glass

- James Mcaffe fictional interview with Carter Glass (at age 139) in 1997: https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/1997/a-conversation-with-carter-glass

Sources:

- Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carter_Glass

- Rixey Smith, Carter Glass: A Biography

- Joe Stinnett, retired editor of The News & Advance and The Roanoke Times

- The Roanoke Times

- Constitution of Virginia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constitution_of_Virginia