Although Frenchman Nicolas Flamel perished in 1417, myths surrounding his work to decipher an alchemical text that would reveal the secret of the Philosopher’s Stone live on. “Guest Book for the McGregor Room” (RG-12/36/1.141).

Now, what if I said the magic does not stop at the McGregor Room gates? What if I told you that deep under Grounds in the bowels of Archives & Special Collections, fantastic beasts hide, spells are cast, and mischief is made?

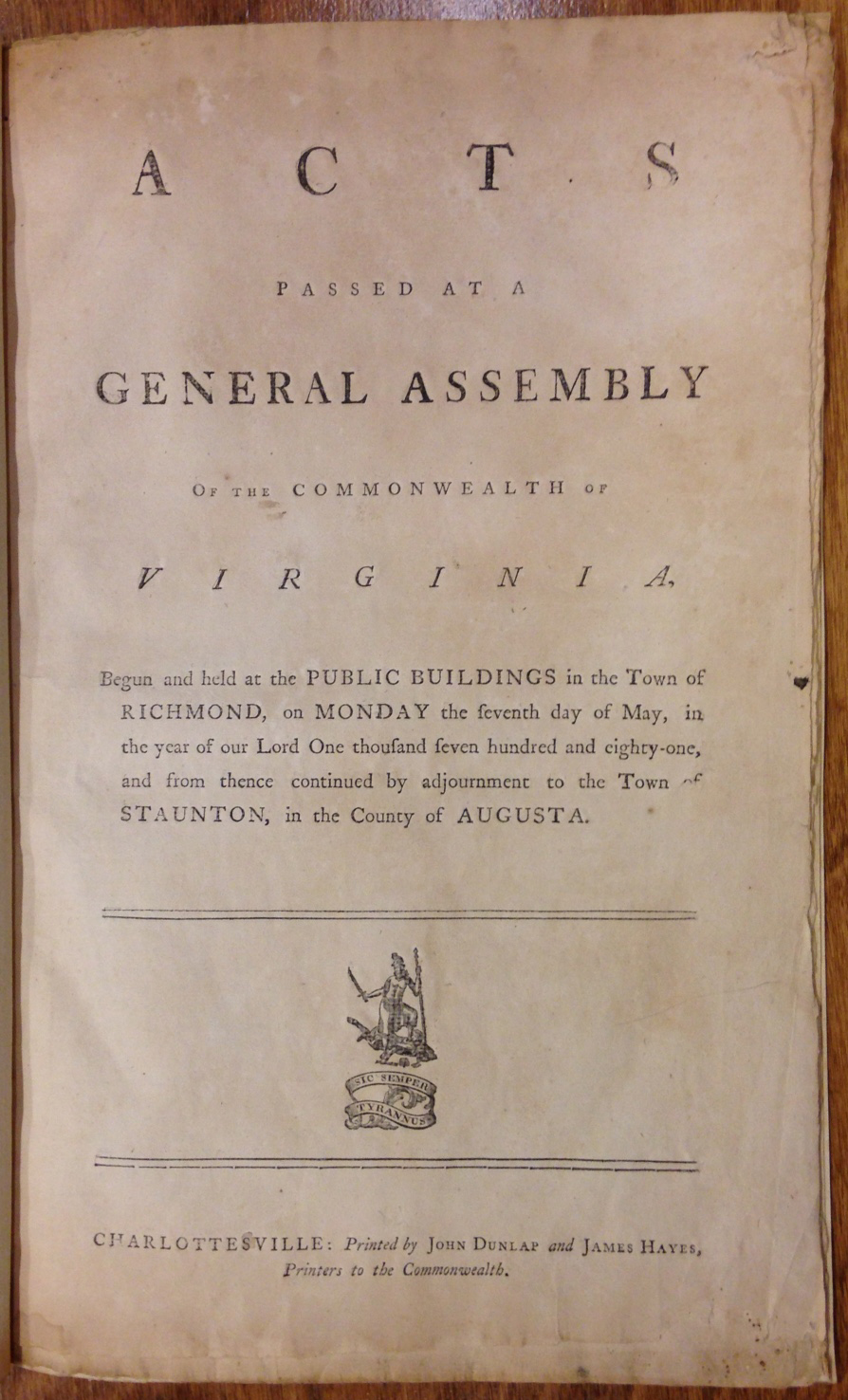

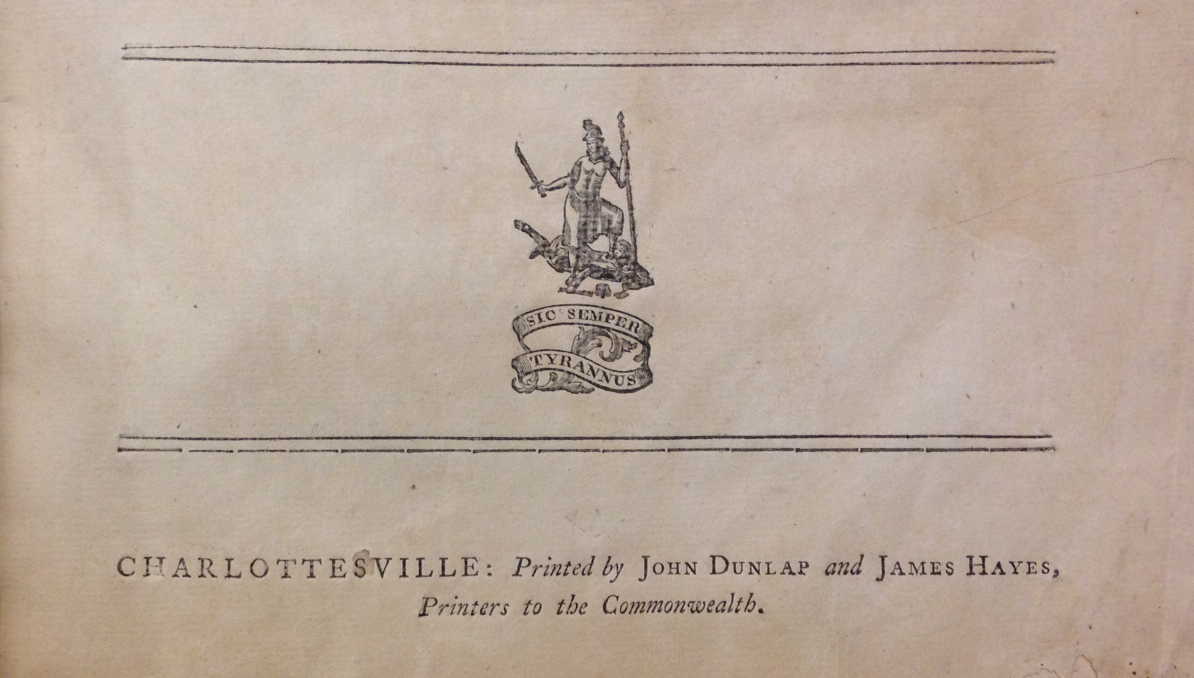

The Discoverie of Witchcraft, published in 1584 by Englishman Reginald Scot.

With a tone reminiscent of Vernon Dursley, Scot set out to prove that there was no such thing as magic. And while his text was central to debates about the implausibility of witchcraft, it also proved to be a useful if not always accurate source on supernatural beliefs and practices

Pages from “The Discoverie of Witchcraft” addressing the disposition and aspects of the planets (M 1584 .S36).

Magical botanicals

While you are unlikely to encounter the mandrake in modern medical texts, Hermione’s definition of the root as “restorative” is historically accurate. Both early Greek and Latin texts, as well as medieval naturalists document the root as being a cure for all diseases, barring death. Ground up the root could even be used in wine, which when drunk could numb patients enough for amputation.

The human-like appearance of the Mandrake in Harry Potter is rooted in first-century Greek physician, Dioscurides’ description of the root as resembling the human form. This belief was reinforced by the medieval doctrine of signatures, which claimed that when eaten, plants that looked like certain body parts could cure what ails those body parts. “The Clutius Botanical Watercolors…” (QK98 .S93 1998).

Magizoology

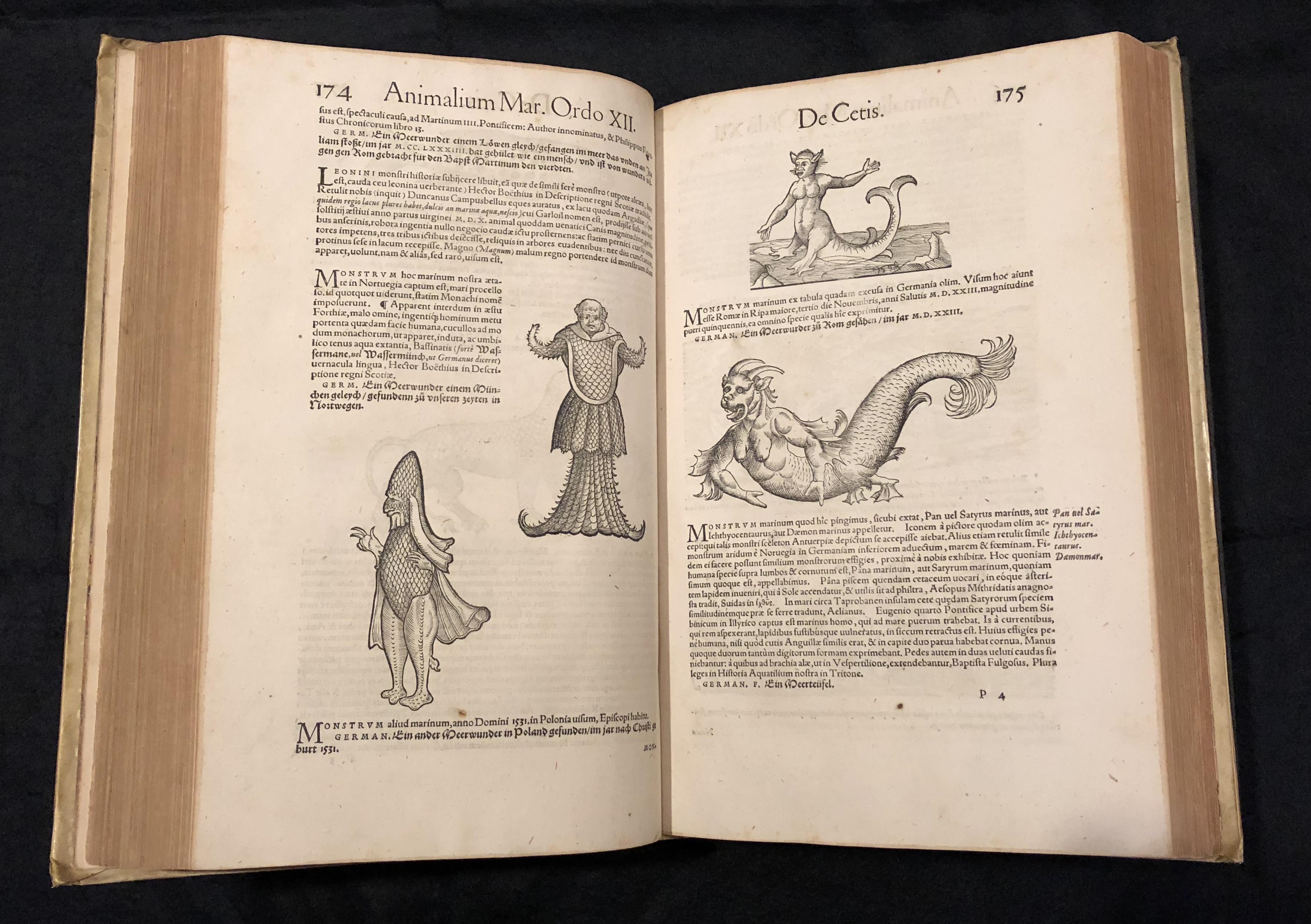

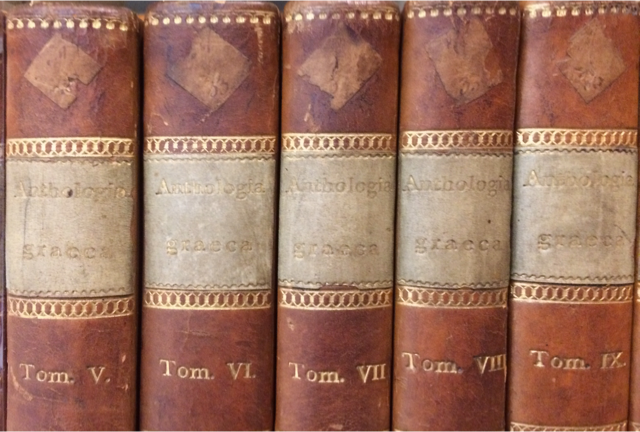

On the subject of magical beasts, Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner authored one of the most widely read natural histories of the Renaissance. Historiae Animalium published from 1551-1558 is a zoological inventory and depicts everything from the mythical to the factual. I have no doubt that this four volume set would have found a place on the shelves in Magizoologist, Newt Scamander’s library.

A book that bites–literally

I know for a fact that we could find this uniquely bound copy of Fantasy & Nonsense: Poems gracing the shelves of our favorite “mad and harry” Professor’s library. This striking book of poetry is the embodiment of what Hagrid considered funny and Malfoy considered hand severing.

Leather bound, edged with shark teeth, and filled with literary references to fantastic beasts, James Whitcomb Riley’s “Fantasy & Nonsense: Poems” is the quintessential “Monster Book of Monsters” (PS2702 .T77 2001). Binder Gabby Cooksey dreamed up this gorgeously executed volume, which actually bites you a little bit every time you turn a page. Come check it out and feel the pain yourself!

Peevish phantoms

He may have been fond of mischief and caused all sorts of trouble, but it was hard not to love Peeves the Poltergeist. Besides, according to Lewis Carroll’s longest poem, Phantasmagoria, ghosts simply have one job to do and that job is to haunt.

Here the ghost from Carroll’s second canto “Hys Fyve Rules” shows his host just how he feels about being treated so rudely (PR4611 .P6 1869).

Horcrux or just an old cup?

You do not need to use the Imperio curse on any of our staff to get your hands on this goblet given to Dr. Gessner Harrison by UVa students attending the 1858-59 class session. Visit the reference desk and we will happily pull it for use in the Reading Room. While we do require you to wear gloves when handling this goblet, I can assure you that it is not because it could be one of Lord Voldemort’s horcruxes.

One of two goblets presented to Dr. Gessner Harrison by UVa students attending the 1858-59 session (MSS 12762).

Weapons against the dark wizard

Harry Minor Wilson, Grand Commander of the Knights Templar of Virginia may not have used his regalia sword to help defeat the most powerful dark wizard of all time, but it would make a fine stand-in for the sword of Gryffindor. The sword will appear to anyone who asks for it. We cannot, however guarantee that when requested, the sword will be delivered in a magical hat by Faux the phoenix.

Harry Minor Wilson’s ceremonial sword as Grand Commander of the Knights Templar of Virginia (MSS 8977-a).

“Happiness can be found, even in the darkest of times, if one only remembers to turn on the light.”

– Albus Dumbledore

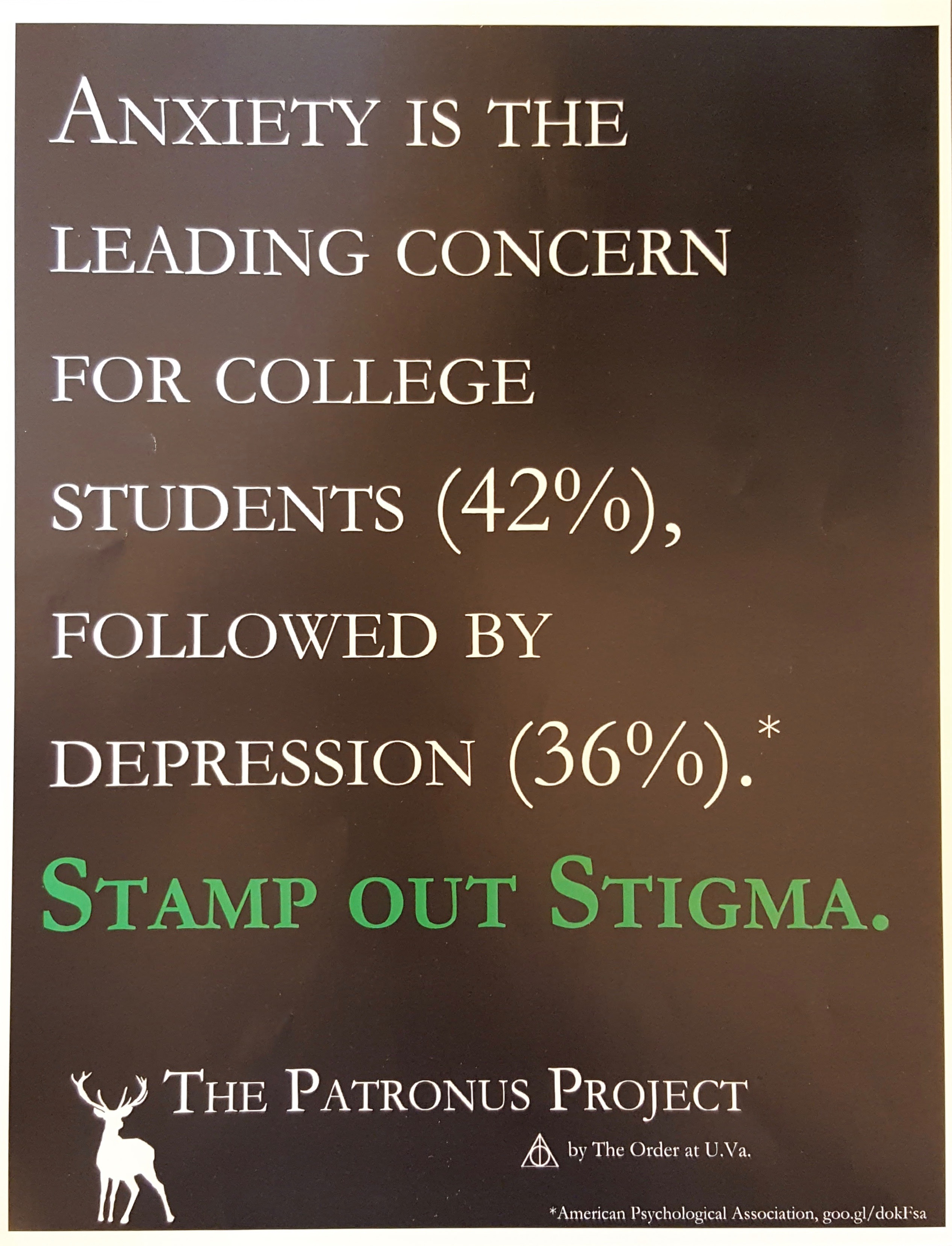

Like Hogwarts end of the year exams, college can be frightful. Not all of us possess Hermione’s zeal for learning, or her time-turner, which would no doubt help with the overwhelming workload. Thankfully, The Order at UVA, the University’s only Harry Potter secret society, established The Patronus Project, which seeks to educate and change the way people talk about metal illness and wellness.

Started by a group of University students who love Harry Potter, The Patronus Project’s mission is to illuminate and banish the stigma surrounding mental illness like Expecto Patronum expels Dementors (Broadside 2015 .O73 no.01).

These are only a few of the many Harry Potter-esque collection items at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. Want to uncover more magical materials? Ask a staff member how! No invisibility cloak required.

Nox!