This week, we are pleased to feature a guest post from Amanda Stuckey, who visited the collections earlier this year as a Lillian Gary Taylor Fellow in American Literature Mary and David Harrison Institute

In an undated (ca. early 20th-century) letter tucked into the first edition of Hannah Foster’s bestselling novel The Coquette (1797) in the Small Library, reader Robert Taylor questions the judgment of the novel’s heroine. Taylor writes that he perused the story of Eliza Wharton, found it “interesting reading,” and even shed a tear or two when he reached the novel’s final lines consisting of the unfortunate protagonist’s epitaph. Yet, Taylor notes, even as he mingled his tears “with those shed upon the tombstone of the ill-fated Eliza; and observe her age as inscribed therein, I am constrained to contend that she was old enough to know better.”

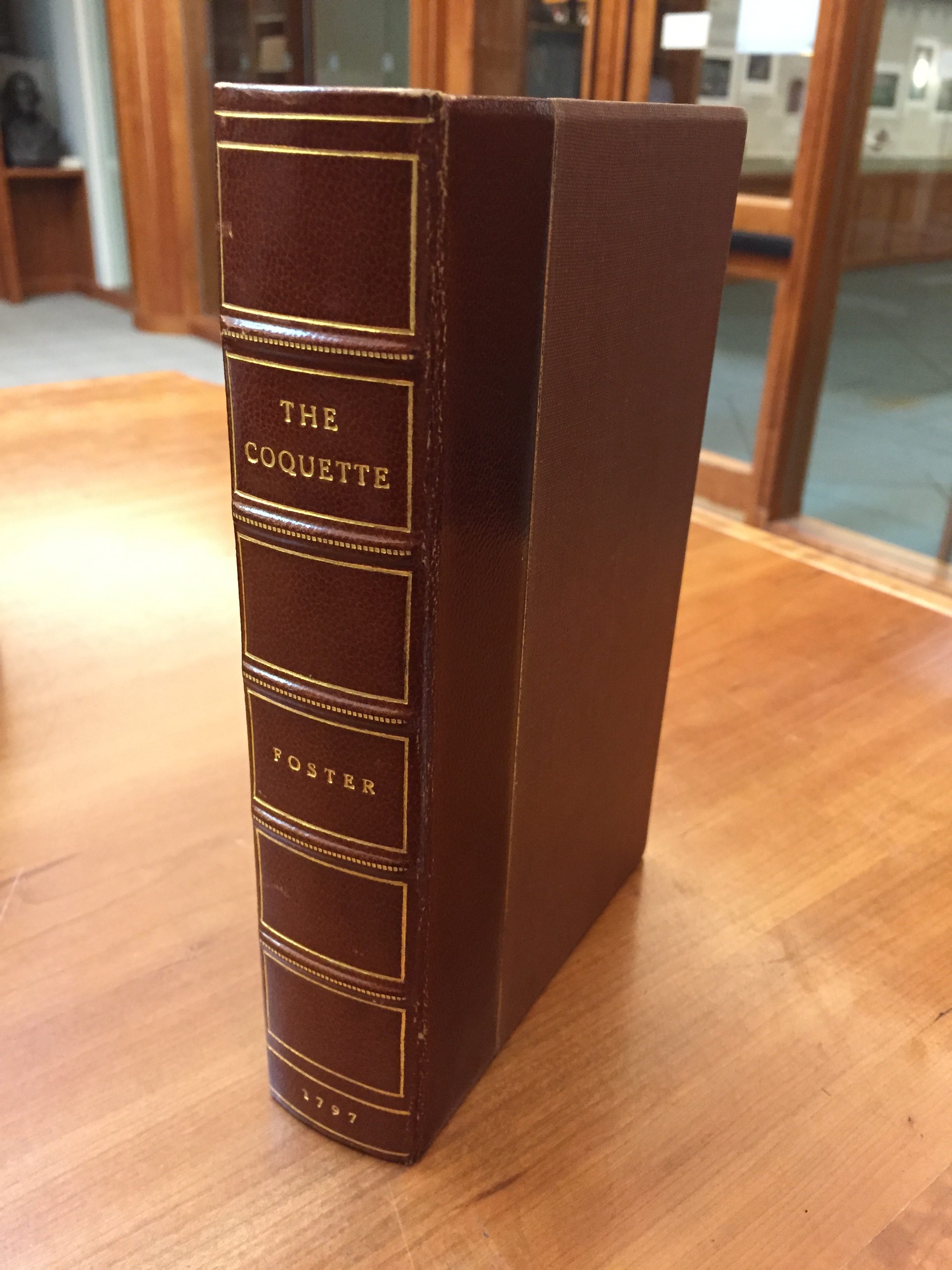

Even though “the book” seems to have all but disappeared in an age of digital reproduction and online catalogues, as contemporary readers we nonetheless exist in a world saturated with text. So much text to be scrolled, contemplated, “liked,” re-tweeted, or simply ignored, that the line between “seeing” text and “reading” it can become unclear. Yet the act of requesting and opening a book like The Coquette from a library that so values the material and physical presence of words, of texts, reminds us that we are here to read. Only seventeen first editions of The Coquette remain, and like many first editions, UVA’s copy has an aura surrounding it; carefully lifting it out of the box cut to fit its exact dimensions, an eager reader might wonder how many other people like Taylor have lifted the unassuming, dulled brown cover to turn tenderly through the weathered but still-sturdy pages. How many others have read on those very pages the story, over two centuries old, of Eliza Wharton, who struggles on the marriage market during the years after the nation-defining struggle of the American Revolution.

The custom box holding the library’s copy of the first edition of The Coquette (Taylor 1797 . F68 C6). Photograph by Molly Schwartzburg

Eliza, an unmarried woman from Connecticut, finds herself caught between two suitors: the rational, respectable Reverend Boyer and the dashing but reprehensible Major Sanford. Just as Eliza’s friends – and her readers – think she is going to make the “right” decision and accept Boyer’s hand in marriage, he catches her in compromising circumstances (by late eighteenth-century standards, at least) in a secluded garden with Sanford. Boyer rescinds his marriage proposal, and by the end of the novel Eliza finds herself pregnant, close to death, and all but abandoned by Sanford, the seducing rake who never planned to marry her in the first place. The catch to which reader Robert Taylor referred? Eliza was thirty-seven when she became pregnant and subsequently died, seemingly bereft of the innocence, virtue, and education that almost four decades of sound friendship and parental guidance sought to instill in her. Eliza’s fatal carelessness in her choice of suitors seemed, to Taylor at least, befitting of a younger woman, one less familiar with the treacherous wiles of men. Indeed, Eliza Wharton could have been mother of her fictional contemporary Charlotte Temple, whose similar fate of seduction, pregnancy, and death at the ripe age of fifteen was the subject of another bestselling novel of the late eighteenth century. “Old enough to know better,” perhaps, Eliza nonetheless is doomed from the novel’s start. Even Foster’s title, a reference to behavior that eighteenth-century audiences associated with flirtatiousness, promiscuity, and an inability to commit, seems to belie the years Eliza had to walk a straight course.

Whenever I read The Coquette, I find myself frustrate–not with Eliza’s seeming inability to make the “right” decision between two men of completely opposite character, but more so with the fact that even now, ten years after I first read the novel, I still read it with a sense of dread, with the feeling that if she’d just settle down with Boyer, she might have a shot at making it out of the novel alive. The genre of seduction fiction into which The Coquette falls is a supremely predictable one, and Eliza is perhaps its most famous example. Each time I read the novel I ask myself, how can I possibly read this differently? How can I assign new meaning to Eliza’s doomed thirty-seven years? What more can I say about her all-too-certain fate, a fate that even Eliza seems to sense as the novel comes to a close?

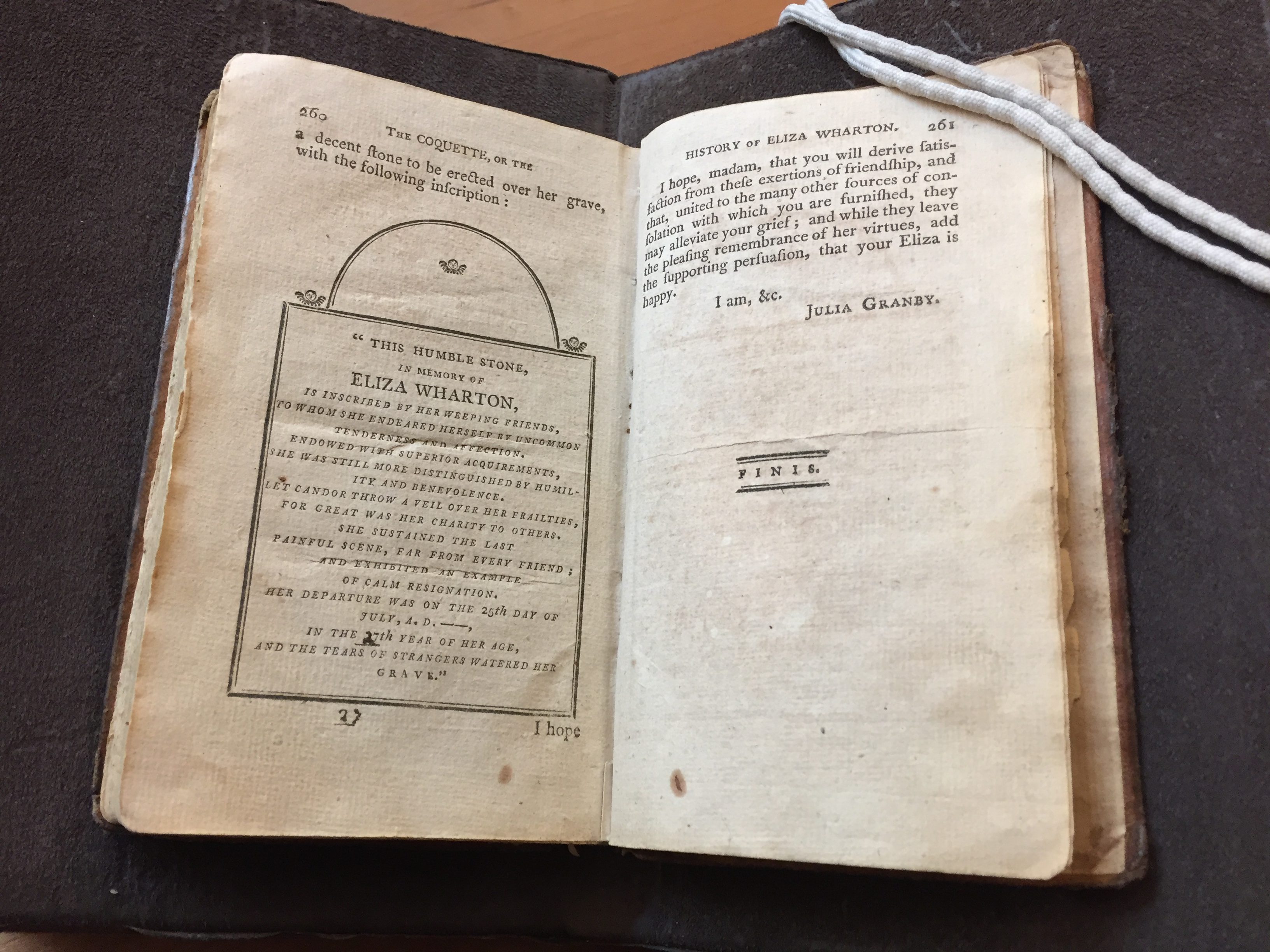

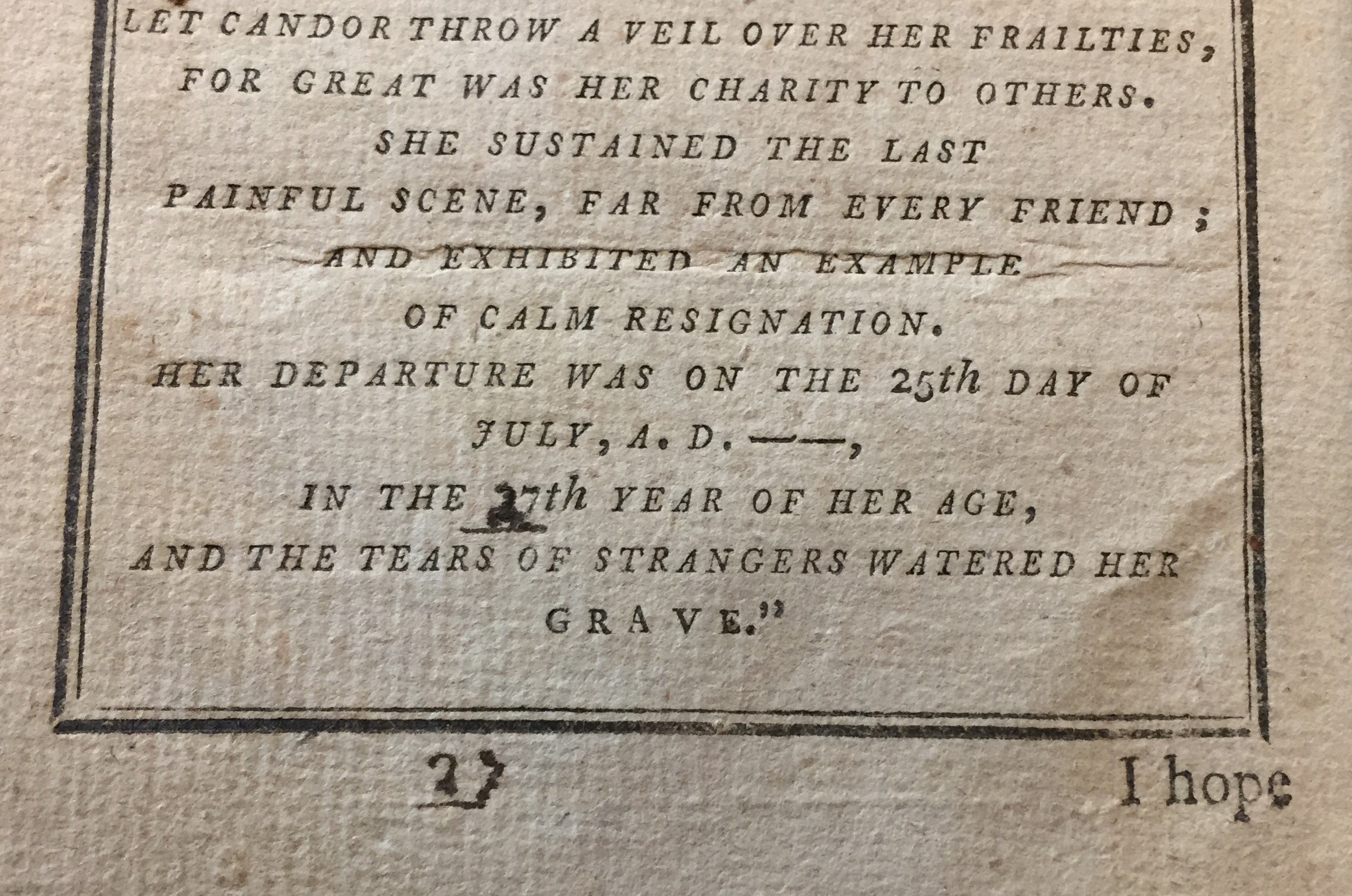

With those questions in mind, I pondered each of the novel’s 242 pages, seeking answers and new clarity. It was not until I reached very last page that I sat up a little straighter in my chair, pulled out of my contemplations by three simple characters in ink:

The final two pages of “The Coquette,” which include a rendering of the text on Eliza’s gravestone. Photograph by Molly Schwartzburg

A detailed image showing where a reader has edited Eliza’s age from 37 to 27. Photograph by Molly Schwartzburg

Twenty-seven? One reader felt so convinced that a woman of thirty-seven could not possibly have fallen victim to one man’s practiced, seductive wiles that this reader had to “correct” the official record of Eliza’s age? So convinced that this reader not only altered Eliza’s epitaph but also felt the need to write it again, to underline it, in case we had any doubt that thirty-seven is way too old to be hanging out in gardens with a known libertine.

Whenever I teach an early American work of fiction, one that is likely digitized through my institution’s library or other vast internet repository, I encourage my students to seek out a physical copy of the book, preferably a first or early edition, housed in a nearby archive or in their university’s own special collections. If we’re lucky, the university’s special collections library will have a first edition, and I ask students to first read a digitized or contemporary scholarly edition of the work and to think about the experience of reading in their present moment. Then students venture out to their special collections library to request a first or early edition of the same novel, to gently lift the cover softened by wear, to delicately turn the pulpy yellowed pages, and to imagine what it might have meant to be reading this work in, say, 1797. Afterward, they write up a brief comparison of the two reading experiences, discussing what surprised them or caught their attention in reading the same book two different ways. These assignments repeatedly demonstrate to me the importance of paying attention to the experience of reading, an experience that today can take so many forms that we almost don’t even notice that we’re reading something when we’re reading it. These assignments have taught my students and me that the experience of reading means different thing to different people, and that we bring our own frames of reference to the text each time we read a book. There is a saying attributed to a Greek philosopher that you can’t step into the same river twice, and the archive continually shows my students and me that you can’t always step into the same book twice. It is different each time we read it, and often that difference comes not from the answers we demand from the book but from the way we let the book speak to us.

And, as it turned out, I’d been asking the wrong questions. I needed to start not with “I” the reader, but with a broader sense of readership, of a recognition that this novel, though it has ridden high crests and low troughs of popularity throughout its life, nonetheless has been read for over two hundred years. The solitary figure of the reader – the “I” – shrinks before The Coquette’s well-worn pages in recognition of just how many fingers have turned them. From the copy in Small Special Collections, modified so minimally yet so insistently, I find myself asking questions that start not with “I” but with how. How have people read this novel? How might previous ways of reading this novel change, affect, influence, the way we read –not just this novel but any text, any book, periodical, or blog? These interjections from the past into our present invite us to look at a familiar text differently, and moreover they invite us to consider the act of reading itself. In a world saturated with multimedia text, the physical presence of the book makes us aware that we’re reading.

That’s what these two numbers, three inked characters, did when I finished up the first edition of The Coquette in Small Special Collections. They spoke to me, caught me off guard, even in the final, oh-so-predictable (I thought) words of the novel. They made me envision another person holding that volume, made me wonder about someone so certain that Eliza just had to be twenty-seven, while I had paid at best scant attention to her age. I have other questions for this novel and its reader(s) – why, for example, was it Eliza’s responsibility to “know better?” For that matter, is thirty-seven really old? Why aren’t we talking about how old Sanford is here? But more important, once I turned the final page, was the way in which this volume – with Robert Taylor’s enclosed letter and the marginalia of an unknown reader – generated these questions from a book I had stepped into once again, a book made almost entirely new thanks to the readings of other readers.

Thanks, Amanda, for sharing your reading room “aha” moment with the blog!