This week we are pleased to feature a guest post by Christy Pottroff, who was in residence at the library last year as a Lillian Gary Taylor Visiting Fellow in American Literature, Mary and David Harrison Institute. Christy is an Andrew W. Mellon Dissertation Fellow in Early Material Texts at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies at the University of Pennsylvania and a Ph.D. candidate in English at Fordham University. Her dissertation is entitled “Citizen Technologies: The U.S. Post Office and the Transformation of Early American Literature.” Thanks so much to Christy for sharing with us her experience studying in our marvelous collections of letters from Liberia.

In 1833, Peyton Skipwith and his family set foot on African soil for the first time. After enduring decades of slavery in the United States, the Skipwith family was eager to start a new life in Liberia. But, after a harrowing fifty-six day journey across the Atlantic Ocean, they soon discovered the conditions were much more difficult than they had been led to believe. The Skipwiths endured disease, harsh climate, inadequate supplies, and conflict with local African tribes–experiences chronicled in a small collection of letters held at the University of Virginia Special Collection Library. These letters, addressed to the Skipwiths’ former owner General John H. Cocke, are at times relentlessly hopeful and at other moments filled with despair. This dissonance between hope and despair is in many ways representative of Liberian Colonization.

[Life Membership Certificate for American Colonization Society], ca. 1840. Certificate. American Colonization Society Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

Each new Liberian had deep roots in the United States; many left behind friends and family they would never see again. And yet, despite the strong ties between Liberia and the United States, very few letters passed between the two countries. The Skipwith letters housed at the University of Virginia Special Collections Library are special indeed.

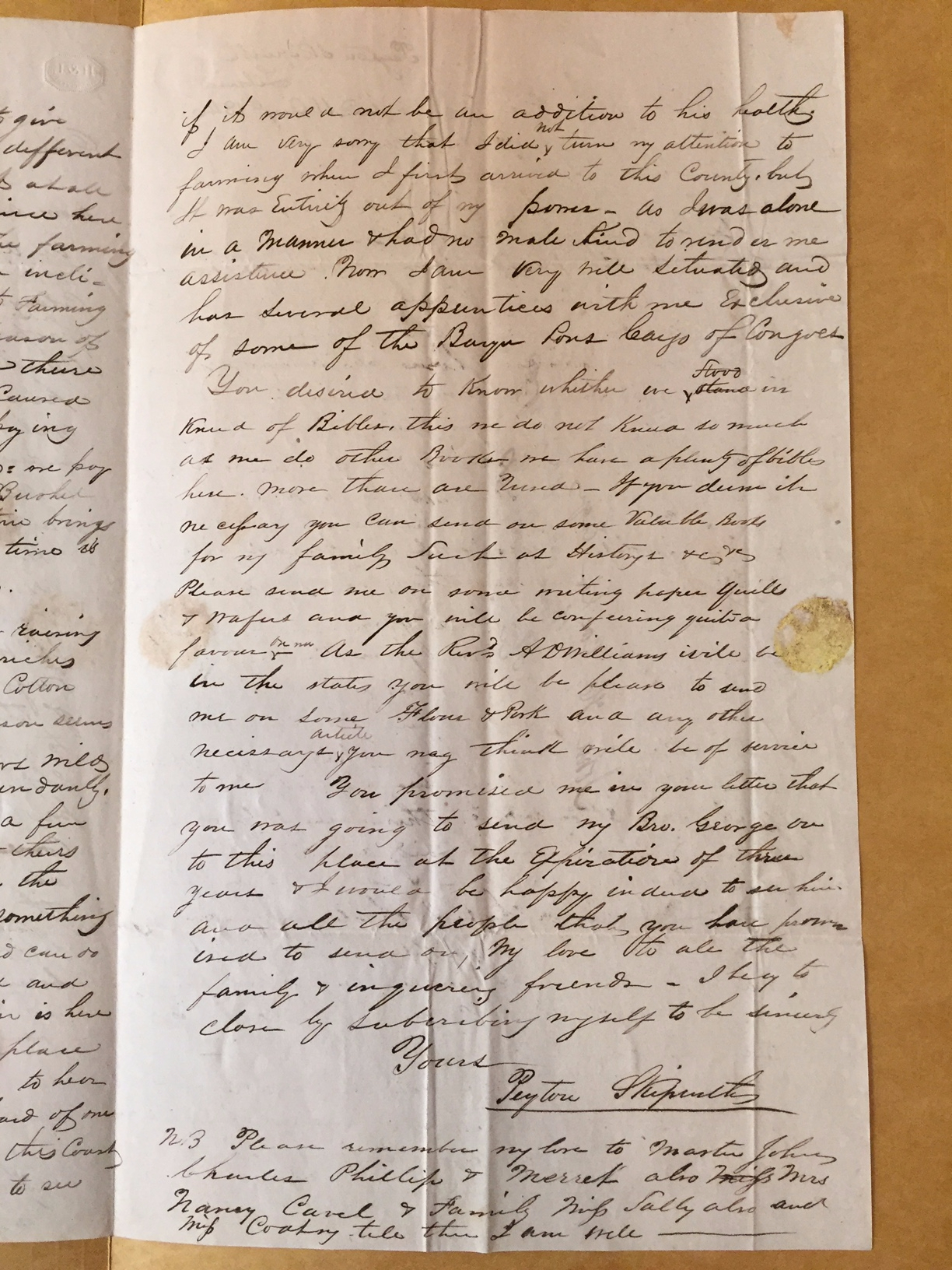

Letter from Peyton Skipwith in Monrovia, June 25th 1846. Cocke Family Papers (MSS 640). Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. Topics covered in the portion shown here are his wish for more farming knowledge and for books other than the Bible, which is widely available.

The dearth of letters between Liberia and the United States is curious. In the middle decades of the nineteenth century, the United States postal system delivered more letters than ever before, and an increasing number of those letters were from countries across the globe. The U.S. Post Office Department facilitated international mail by entering into bilateral postal treaties that guaranteed easy and inexpensive communication and commerce beyond the nation’s borders. In 1851, the United States maintained postal treaties with every country in Europe. The Postmaster General was proud to report new treaties with Algeria, Hong Kong, St. Kitts and Nevis, Beirut, and many more.

The United States did not enter a postal treaty with Liberia until 1879 (when Liberia was admitted to the newly established Universal Postal Union). Despite the special relationship between the two countries in the first half of the nineteenth century, there was no standardized way to send a letter between them. Liberia did have a rudimentary postal system, though its origins and development are difficult to track. In the 1850s, the Liberian government entered into postal treaties with Great Britain, France, and Germany. It was through these roundabout channels that the existing Liberian letters to the United States traveled. As a contemporary American Colonization Society member writes:

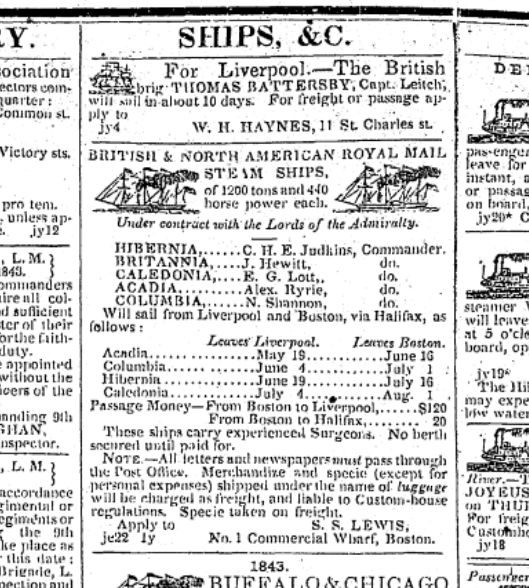

Great Britain…sends a weekly line of steamers to the Western Coast of Africa, which touch at Liberia. In fact, by a postal treaty, the mails between Liberia and America go by these steamers, and then by the British steamships between England and the United States!

This roundabout mail channel between the U.S. and Liberia meant that letters were twice as expensive (as they needed postage in two different postal systems) and were at much greater risk for delay, loss, or misdelivery.

Advertisement for mail transport in The New York Herald, November 12, 1844. (Source: Readex Early American Newspapers Database. Accessed: October 23, 2016)

For Peyton Skipwith and his family, the absence of a postal treaty had great consequences. They left behind their homeland, friends, and family–and had no reliable way to communicate with loved ones left behind. One of the most striking things about the Skipwith family letters is the frequent reference to lapses in communication. In an 1835 letter, Peyton writes “This is the third letter that I have wrote to you and have received no answer.” And a year later, he expresses frustration because “I write by almost every opportunity but cannot tell how it comes to pass that only two of my letters have been received.” Later, in 1839, he writes “Reverend Colin Teague should have brought [your letter] to me but he did not reach his home but died…which was a great disappointment to me…I am always anxious to hear from you all.”

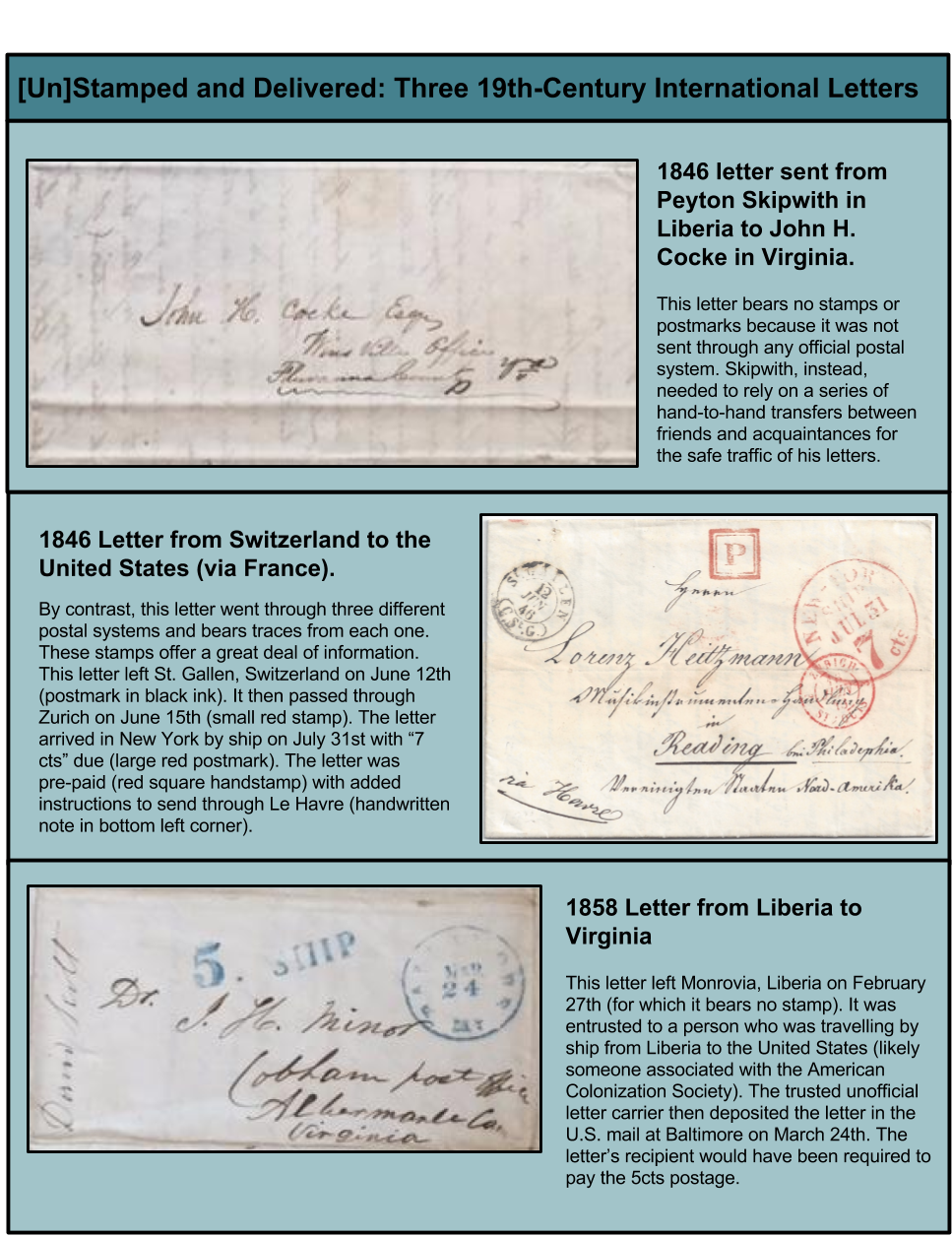

Top: Letter from Peyton Skipwith to John Hartwell Cocke, June 25, 1846. John Hartwell Cocke Papers 1725-1949 ( MSS 640, etc. Box 117). Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

Center: Letter from Switzerland, via France, to U.S. Schaefer Collection. (Source: Frajola Philatelist. Accessed: October 23, 2016. http://www.rfrajola.com/sale/RFSaleP6.htm)

Bottom: Letter from Judy Hardon to Howell Lewis, Dr. James H. Minor, and Frank Nelson, February 27 1858. Letters From Former Slaves of James Hunter Terrell Settled in Liberia. 1857-1866 (MSS 10460, 10460-a). Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

The absence of any American-Liberian postal treaty is perplexing. Both countries had entered into other postal treaties during the period, and the United States was sending mail steamers across much greater distances for postal purposes. This unsettled postal state was most likely the result of an ideological problem.

The same rationale for sending free African Americans to Liberia likely permeated into contemporary international postal policy. Free people of color were thought to threaten the stability of slave society, and their proximity to enslaved Americans was considered dangerous. A single letter cannot collapse geographical distance, but it can do a great deal to shrink ideological distances. With a postal treaty, new Liberians would have had the freedom to send letters to free and enslaved friends and family members in the United States. They could have shared ideas, money, or other resources with privacy, dispatch, and ease. The thought of regular correspondence between free and enslaved African Americans is very likely what kept the United States Post Office Department from opening up any reliable public channel of communication to and from Liberia.

The absence of an American-Liberian postal treaty did not solve a real problem; the likelihood of conspiratorial international communication between African Americans was quite slim. Instead, the treaty’s absence created countless problems for the Skipwiths and their fellow Liberian emigrants. Peyton, for example, tried in vain to send a letter to his brother George before his death. Another Americo-Liberian, William Douglass, desperately sought $50 that had been lost in transit between Liberia and the United States (worth over $1,300 in today’s currency). Without a reliable international postal treaty these instances of lost letters and impossible communication were dishearteningly common. In light of these institutional barriers, that these letters from Liberia ever arrived at the University of Virginia Special Collections Library is itself a small miracle.