The following miscellany of recent book acquisitions is intended, not for those basking and basting on a sandy beach, but for those who prefer the cool, calm, and comfortable surroundings of the Special Collections reading room under Grounds. Take a break from tanning and pay us a summer visit!

Plate 13 in William M. Woollett, Old homes made new: being a collection of plans … illustrating the alteration and remodelling of several suburban residences (New York: A. J. Bicknell & Co., 1878).

A new addition to our extensive architecture holdings reminds us that architecture can be a process of renovation as well as creation. In Old homes made new (New York: A. J. Bicknell, 1878), Albany, N.Y. architect William M. Woollett offers remodeling advice to American homeowners. Stuck with a New England saltbox, Federal mansion, Greek Revival temple, or Gothic Revival embarrassment? Through before-and-after floor plans and exterior views, Woollett shows how to update one’s ancestral family home to the then-fashionable Queen Anne style. The work closes with exterior photographs of a mid-18th-century home in Ridgefield, Conn. that Woollett had transformed into a Victorian showpiece. Architectural historians, historic preservationists, and others charged with reverse-engineering historic structures may find Woollett’s approach illuminating.

When money is THE object: one way to select a spouse in the Antebellum South, as explicated in S. S. Hall, The bliss of marriage: or, How to get a rich wife. (New Orleans: J. B. Steel, 1858)

But the nest must be built before it can be renovated. Populating that nest is the subject of S. S. Hall’s rare and unusual Bliss of marriage: or, How to get a rich wife (New Orleans: J. B. Steel, 1858). In some respects similar to the many courtship guides published in Antebellum America, Hall’s work is in other ways different in claiming to be written for a Southern audience. A New Orleans attorney (and not the prolific dime novel writer “Buckskin Sam” Hall, as often claimed), Hall based this work on three years’ “personal experience and general observation.” After offering advice such as “Marry no woman who sleeps till breakfast,” Hall devotes most of the book to the art of marrying well, and well-to-do. At the end is a 15-page appendix of nearly 400 wealthy “unmarried young ladies and gentlemen”—the former identified only by initials, the latter by full name—residing in various Louisiana, Mississippi, and Kentucky towns, with their estimated net worth. One wonders how successfully Hall followed his own advice.

Title page to Wänskaps och handels tractat emellan Hans Maj:t konungen af Swerige och the Förente staterne i Norra America … = Traité d’amitié et de commerce entre Sa Majesté le roi de Suède et les Etats-unis de l’Amérique septentrionale … (Stockholm: Kongl. Tryckeriet, 1785)

To the McGregor Library of American History we have added the rare Swedish printing (Stockholm, 1785) of the landmark 1783 Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Sweden and the United States. In September 1782, with the American Revolution drawing to a close, Congress empowered John Adams, John Jay, Henry Laurens, and Benjamin Franklin to negotiate peace with Britain. At the same time Franklin was appointed minister to Sweden, and he quickly entered into discussions with his Swedish counterpart. A treaty was concluded on April 3, 1783, and ratified by both countries later that year. Sweden thus became the first neutral country to officially recognize the United States. The treaty’s text is printed in parallel columns in Swedish and French, with Congress’s act of ratification appended in English.

![A detail from one of the massive (53 x 36 cm.) engraved plates in André François Roland, Le grand art d’ecrire. (Paris: Chez Esnauts et Rapilly, [between 1777 and 1791]](https://smallnotes.library.virginia.edu/files/2013/06/xyz_0001.jpg)

A detail from one of the massive (53 x 36 cm.) engraved plates in André François Roland, Le grand art d’ecrire. (Paris: Chez Esnauts et Rapilly, [between 1777 and 1791]

![[Harvey Newcomb], The "Negro pew": being an inquiry concerning the propriety of distinctions in the House of God, on account of color. (Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1837)](https://smallnotes.library.virginia.edu/files/2013/06/def_0002.jpg)

[Harvey Newcomb], The “Negro pew”: being an inquiry concerning the propriety of distinctions in the House of God, on account of color. (Boston: Isaac Knapp, 1837)

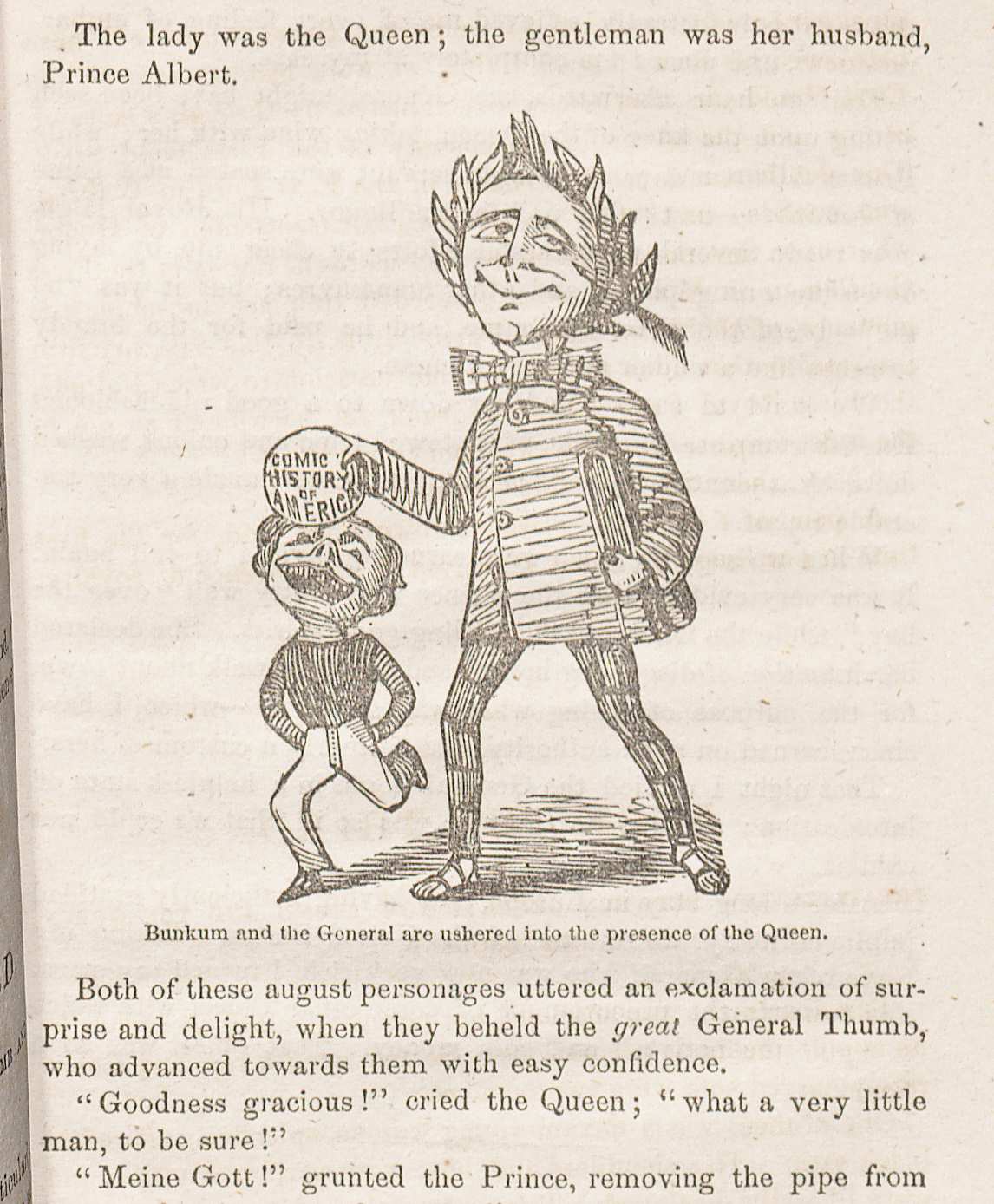

P. T. Barnum (er, Petite Bunkum) and General Tom Thumb make the acquaintance of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, in The autobiography of Petite Bunkum, the showman. (New York: P. F. Harris, 1855)

The great American showman P. T. Barnum makes innumerable cameo appearances under Grounds in Special Collections’ rich holdings relating to 19th-century American literature and culture, hence we were happy to acquire a rare Barnum parody. In 1855, just before financial reversals added further notoriety to his name, Barnum published a best-selling autobiography “written by himself.” The book was quickly and affectionately parodied in The autobiography of Petite Bunkum, the showman (New York: P. F. Harris, 1855), also (and anonymously) “written by himself.” “In these pages I have adhered to the truth as closely as might suit my purpose,” Bunkum allows, before relating his comical rise to fame and fortune. Of the supporting characters, only General Tom Thumb retains his full name. Others receive a modest fig leaf—Joyce Heath (for Joyce Heth, billed as George Washington’s 160-year-old nurse), Jenny [Lind] the Swedish Nightingale, the Fudge Mermaid, the Whiskered Woman—and all are caricatured in image as well as in word.

It’s 5 p.m. and we must close for the day, but perhaps there’s still time for the beach?