Here at U.Va. Thomas Jefferson looms large both on, and under, Grounds. It is only fitting that the Small Special Collections Library holds one of the world’s best collections of Jefferson manuscripts. Some form part of the U.Va. Archives, for Jefferson founded the university and served as its first Rector from 1816 until his death in 1826. Others have been placed in our care by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, which owns and operates Monticello. Still more have been acquired over the years through the generosity of many donors, who have either entrusted their Jefferson manuscripts to us or given funds for new acquisitions.

Jefferson is estimated to have written some 19,000 letters during his lifetime. A great many survive, and a significant number of Jefferson letters and documents remain in private hands. Given our finite resources, Special Collections can by no means acquire every Jefferson manuscript that comes on the market. Instead we patiently seek items of high research value, especially the previously unknown and unpublished. Our latest Jefferson acquisition arrived just last week, and it fits the bill perfectly: an early and highly significant manuscript, previously unknown and unpublished, which is the mate of a manuscript already at U.Va.

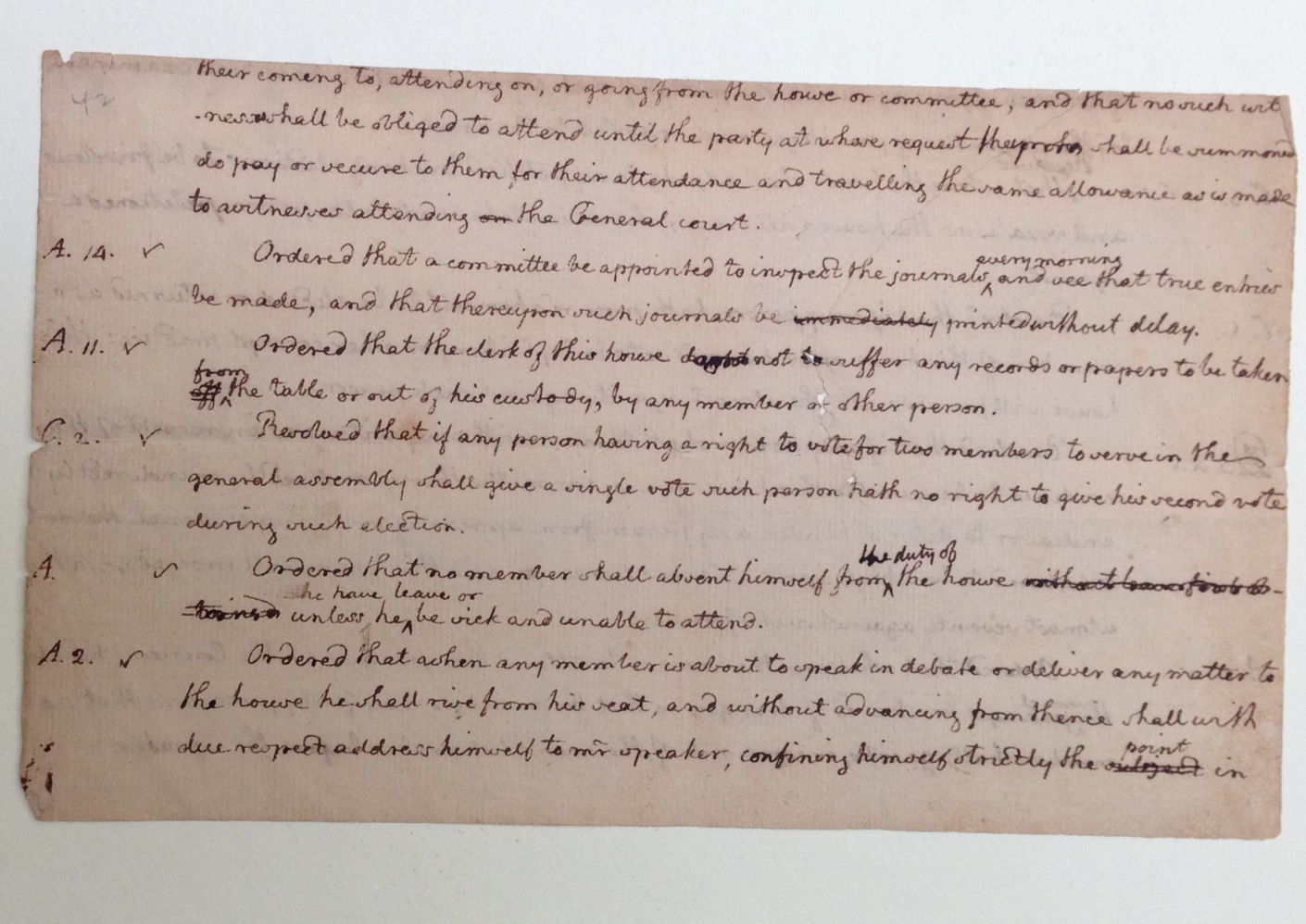

Our newly acquired Thomas Jefferson manuscript: the bottom half of a leaf containing his draft revision (ca. November 1769) of the rules under which the Virginia House of Burgesses conducted its business. (Photo by Molly Schwartzburg)

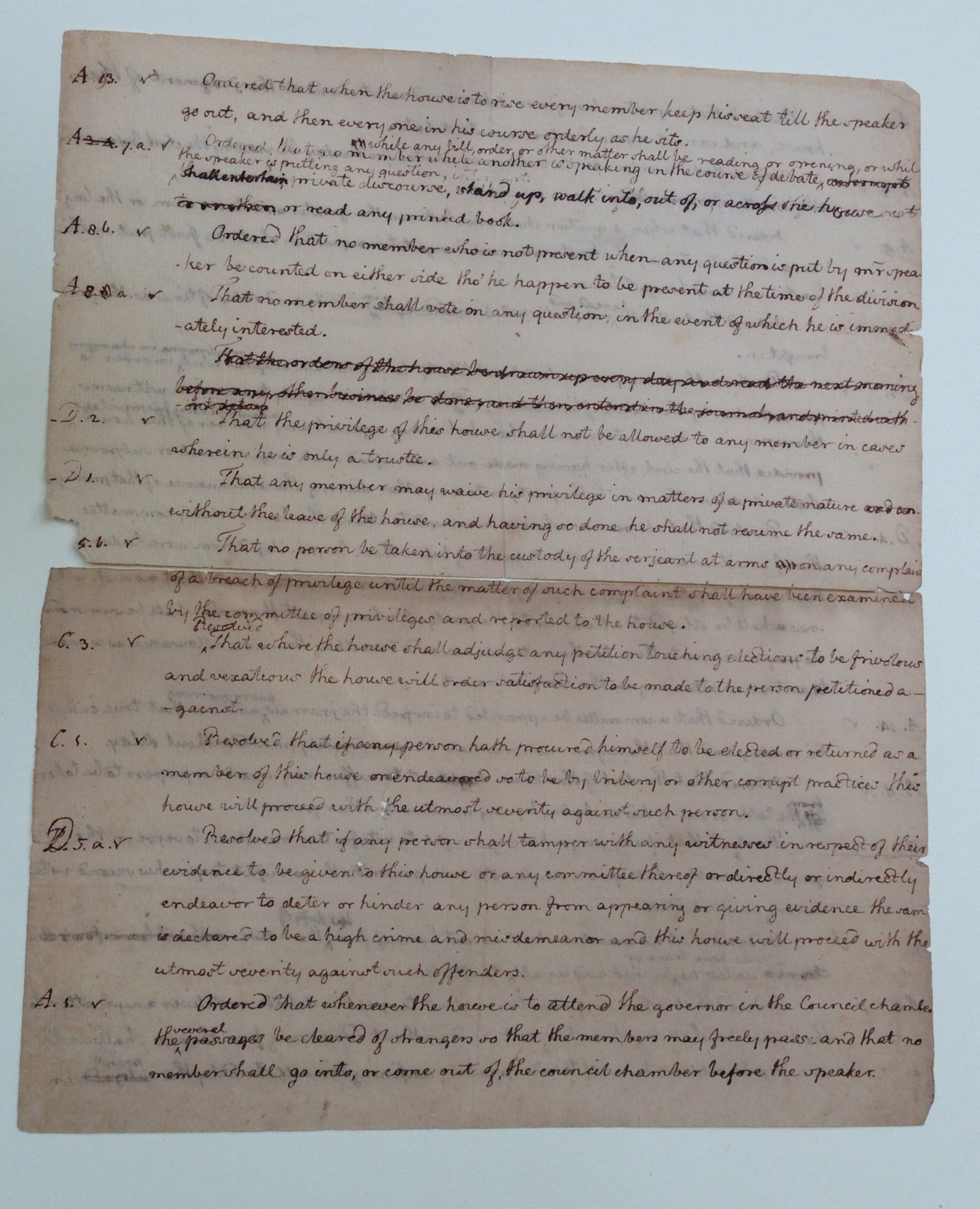

But the story begins in 1988, when Special Collections learned of an unrecorded Jefferson manuscript being offered in an upstate New York auction. The document, for which we were high bidder, was identified by editors at the Papers of Thomas Jefferson as the top half of a leaf, written on both sides, containing Jefferson’s draft revision of the rules by which Virginia’s House of Burgesses conducted its business. Jefferson began his political career in 1769 when, at the age of 26, he took a seat in the House of Burgesses in Williamsburg. In November of that year he was appointed to a committee chaired by Edmund Pendleton, who assigned Jefferson the task of drafting new rules for the House. Jefferson’s draft was refined in committee before being approved by the House of Burgesses on December 8, 1769. These rules guided its deliberations in the crucial years leading up to the American Revolution.

In 1997 U.Va.’s incomplete manuscript was published in volume 27 of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, where it was described as Jefferson’s “earliest surviving documentary contribution as a public official to promoting the orderly conduct of legislative business, a subject of enduring interest that culminated during his vice-presidency with the publication in 1801 of his Manual of Parliamentary Practice, which still helps to guide parliamentary procedure in the United States Congress today.” In some respects it also prefigures Jefferson’s later committee assignment, in June of 1776, to draft another key document: the Declaration of Independence.

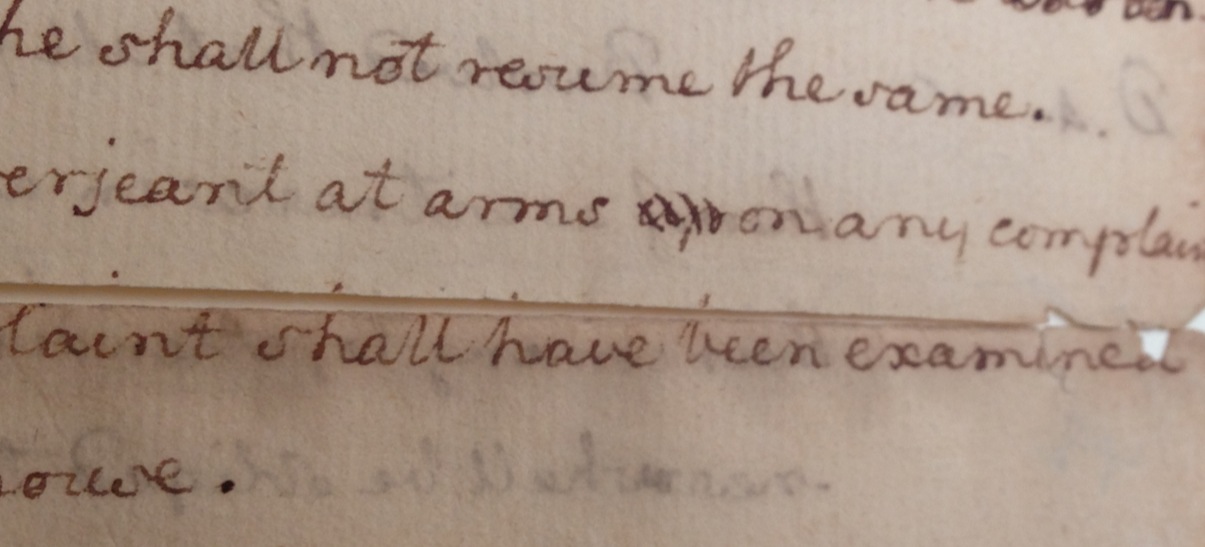

Proof that the document’s top and bottom halves were once joined: from left to right, note how the dot of the i and ascenders of the letters h, h and b align perfectly across the divide. (Photo by Molly Schwartzburg)

Last month, on the opening night of the New York Antiquarian Book Fair, I was called over to a dealer’s booth, where a modest scrap of paper was placed in my hands. It was none other than the missing bottom half of Jefferson’s 1769 draft! Negotiations were quickly concluded, and last week the two halves were happily, and permanently, reunited. Once the newly acquired manuscript is fully studied and published, we will know far more about this key episode in Jefferson’s nascent political career and the development of his political thinking.

Reunited at last! The top half is cataloged as MSS 10803; the newly acquired bottom half is presently being accessioned. (Photo by Molly Schwartzburg)

Coincidentally, an exhibition of some of our best Jefferson manuscripts is on view under Grounds through June 8. Curated in cooperation with Monticello staff, “Thomas Jefferson Revealed” briefly surveys Jefferson’s pre-presidential years and his life at Monticello. Highlights include a ledger recording Jefferson’s Williamsburg book purchases from 1764-1766; his annotated copy of the London, 1787 edition of Notes on the State of Virginia; a lock of Jefferson’s hair taken on his deathbed, and a letter describing his last hours; and the manuscript autobiography of Isaac Jefferson, a Monticello slave.