In mid-February, I took a trip out to the San Francisco Bay Area to attend the biennial Codex International Book Fair, which began in 2007 and has emerged as the premier venue for artists, printers, and dealers to display and sell artists’ books, fine press editions, and book art, with a particular emphasis on fine limited editions. Held this year at the beautiful Craneway Pavilion in Richmond, which overlooks the San Francisco Bay, the fair was a light-filled, dazzling display of creative production and craftsmanship. This new venue was necessitated by the growing number of visitors and exhibitors at the last fair. If, as they say, the book is a dying medium, “they” haven’t seen the diverse productions of book artists in recent decades, nor have they observed the increasing visibility of artists’ books beyond the small world of book artists and collectors.

I went to the fair seeking items that would help us expand Special Collections’ already robust and diverse collection of artists’ books and fine press editions, which are used widely in teaching by academic and Rare Book School faculty alike. I left having met dozens of artists, printers, and publishers from around the world, and waited eagerly for the arrival of my various purchases for the collection.

A great artist’s book is like a great poem. When you read such a poem the first time, you see it whole, appreciate its beauty and formal sophistication, grasp it fully on some level. When you reread it, you suddenly find that you do not understand it at all, and you’re not even sure what questions you need to ask of the poem before you can begin to understand it again. The deep pleasure that poetry brings me begins when I start formulating these questions, and it does not end until I must put down the poem to go wash the dishes or answer my email. It is this type of engagement I seek when I am selecting artists’ books for the collection.

I had this kind of experience when I came across the elegant Spandrel, a collaboration between Frank Giampietro and Denise Bookwalter, published by Small Craft Advisory Press at Florida State University, which had a booth at the fair:

The front cover of Spandrel. The book is very thick and has the appearance of great heft, but is surprisingly light when you pick it up. This is due to the cut interior and the Hosho paper, which is thick and fluffy. (Photo by Molly Schwartzburg)

The title is an architectural term that refers to the empty space at the side of an arch (I can’t seem to explain this in words–I recommend that you Google it!). The press provides an excellent description of the book’s form: “Spandrel uses traditional and non-traditional processes to play with the reading of a poem. One poem is on the first page and slowly transforms through the 150 pages into the second poem, which is on the last page. In the middle of the book the text is unreadable but as the viewer nears the end the text comes back into focus.”

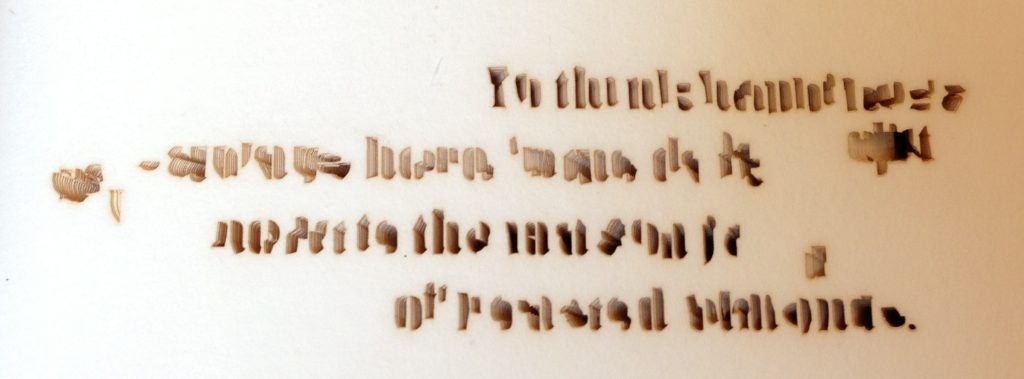

What this description doesn’t note is that none of this is printed: the text is an absence, cut out of the book with a laser, its font like a stencil. The shadows produced by the stacks of slowly shifting cuts on subsequent pages produces the visible text:

A detail view of two words on the first page of the book reveals the edges of cuts below. (Photo by Molly Schwartzburg)

The laser printing very slightly singes the page, producing a tinge of brown around each letter. Near parallels between the text of the poem and the form of the book begin to emerge as one considers the opening page: the singed pages and “roasted almonds” share the same color. The receding darkness behind each cut on the page seems somehow connected to the “dark cabinet.” There are disjunctions too: laser cutting is a relatively new technology associated with high-tech industry, while mason jars evoke homemade preserves. But this jar doesn’t hold preserves, just as this book doesn’t hold printing. Both hold something singed by heat. There is a sort of symmetry here.

But what happens next is more interesting. Looking at the first page, one might imagine that the entire text block (the “stack” of all of the book’s pages), was laser cut in one step. Page after page, the same poem appears again and again, but soon, it begins to shift slightly, and then more, until it moves towards illegibility and then back to legibility. Each page is cut separately from a series of digitally generated tempates:

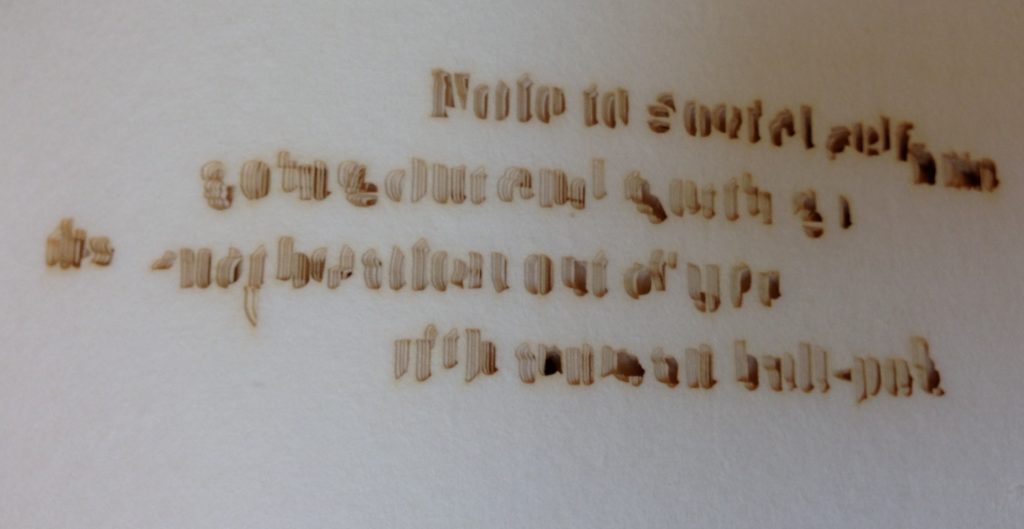

In the final pages, the text becomes clearer and clearer, and lighter and lighter, as there are fewer shadows to define the text. It finally resolves into this chilling poem, which takes more effort to read than the first one did:

The image of domestic comfort in the opening poem is replaced by one of urban violence in the latter: ball-peen hammers are a dangerous weapon. The poem’s opening symbol of happiness–whole almonds protected in a clear jar inside a closed cupboard inside a home–is replaced by an image of the layers of someone’s skin, then skull, then brain being violently broken, shattered, and compressed respectively by a heavy blow. The lack of human actors in the first poem suddenly becomes apparent.

The second poem seeks actively to shock: mason jars are replaced by snot, and the strange elegance of the opening page is utterly lost.The reader begins shifting back and forth between the two poems, seeking to understand the differences between them, the justification for their juxtaposition, the physical location in which one word or phrase replaces another. I find my own mind running down multiple interpretive paths: which wins out in this book, happiness or the social self? What would happen if the two poems traded places, and it began with the social self and ended with happiness? Once I come to the word “ball peen” this suddenly seems to be a book about a man, since I only associate this kind of violence with men. Is he the subject of both poems? Is there a woman in the domestic space of the kitchen? And why are there almonds in the jar instead of preserves? And while I’m at it, what does any of this have to do with spandrels? It has something to do with empty spaces, with round holes produced by a hammer, with jars, cupboards. With absence–an empty house with an empty space in a cupboard, and a “social self” who experiences only violence. What lesson am I to learn from all of this? What is the poet telling me? What is the book telling me?

There are likely no clear answers to these questions; the two poems are not entirely symmetrical, do not have some kind of straightforward causal relationship. If they did, the book would fail because it would be clever, even smug. Instead, its mysterious, discomfitting texts and physical form together produce a fertile space for contemplating the poetry, heightening the reader’s capacity to observe the very specific elements of sentences, phrases, and lines. It is a dazzling example of the productive relationship that can exist between a book and its contents.

This is just one of the many wonderful items found at the fair. Too bad I have to wait two years for the next one!

If you get overwhelmed looking at books at Codex, step just outside and take in the view. The Bay Bridge may be seen on the left. (Photo by Molly Schwartzburg)