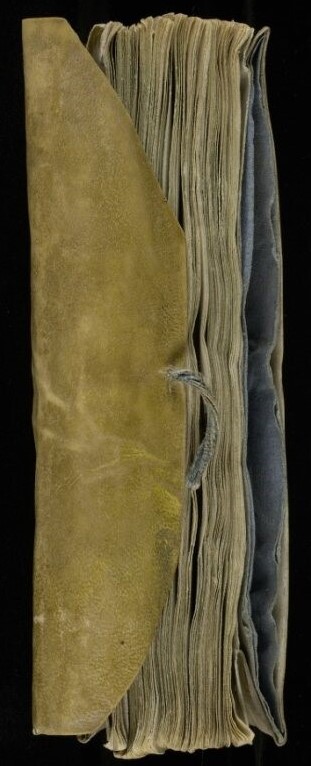

This post, by Ellen Welch, Manuscript and Archives Processor, is about the recent acquisition: Illustrated Manuscript Confessory for Deaf People (MSS 16803).

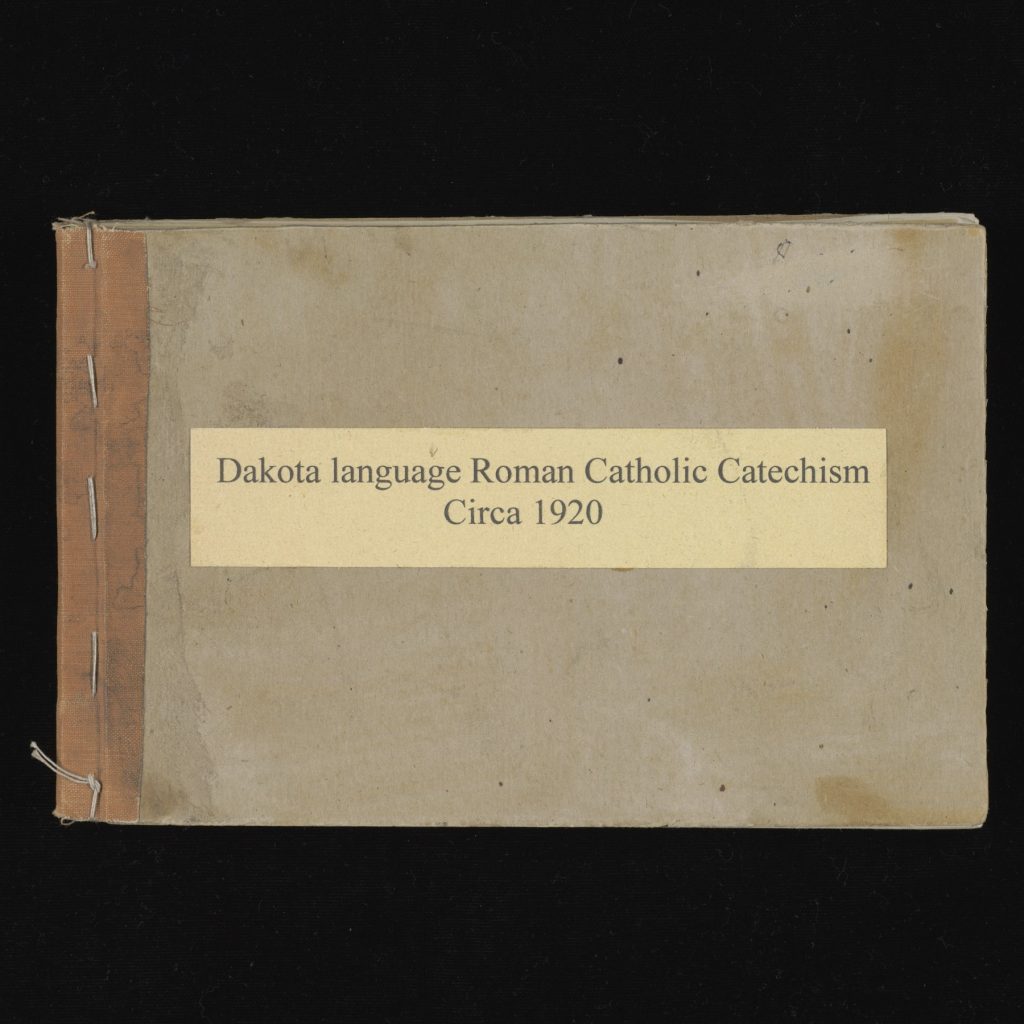

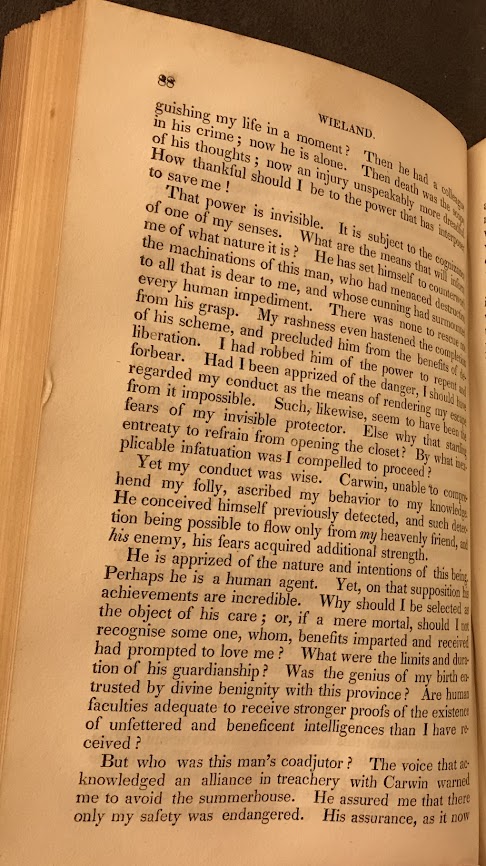

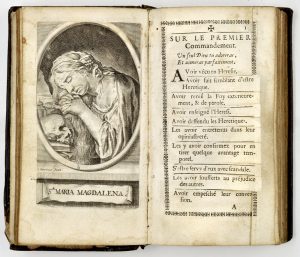

A single leather-bound illustrated manuscript for Deaf persons to confess their sins. They could identify their sins by the illustrations and ask to be absolved. Called a Confessory, it was made in Flanders or the Netherlands roughly between 1770 and 1790.

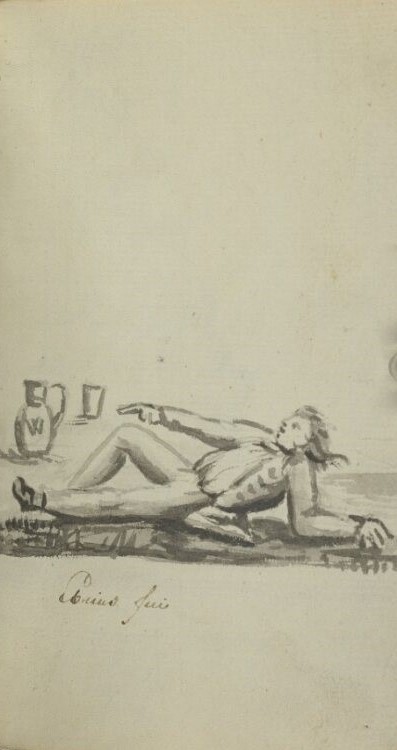

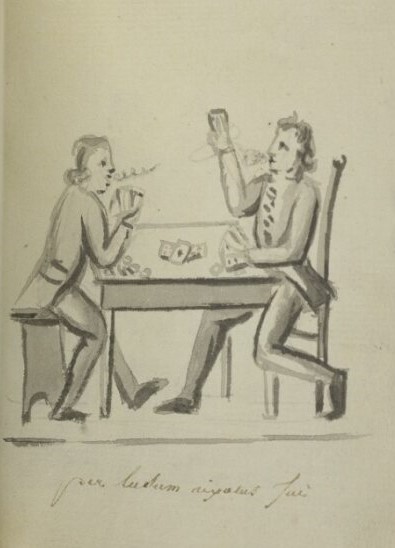

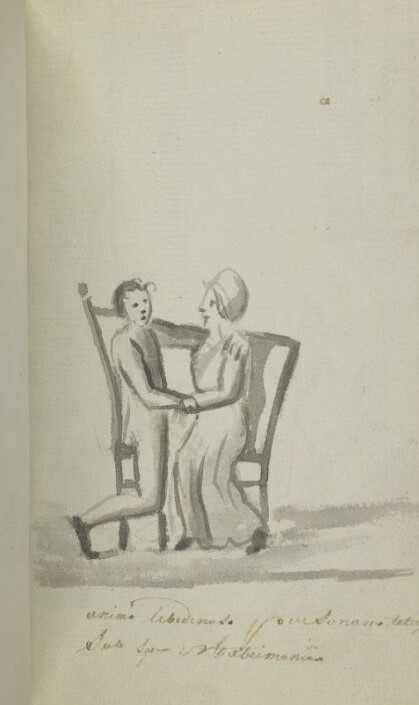

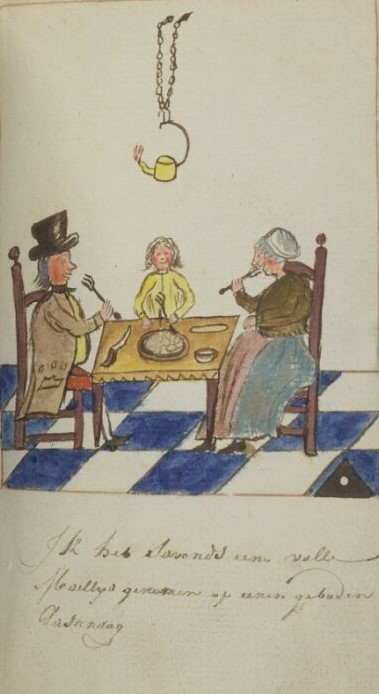

This leather-bound manuscript serves as a confessional aid, containing illustrations depicting a variety of sins from which a Deaf individual could show a picture of their sin to the priest and ask for absolution. The simple drawings depict sins such as being distracted in or late for church, missing confession, gluttony, gossip, theft, gambling, drunkenness, fighting, wishing another person dead, and lust, or “inappropriate libido”! This illustrated confessory was made in either Flanders or the Netherlands, between 1770 and 1790, and was probably created at a school for Deaf people.

Throughout history, societies have misunderstood and mistreated Deaf people because they could not communicate in the same way others could. As long ago as antiquity, influential figures like the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC) falsely believed that Deaf people were incapable of reason (1). Legal tradition across Europe barred Deaf people from inheriting property, purchasing land, and getting married. Within Christian communities, Deaf people were often excluded because it was wrongly believed that they were not able to receive the word of God and the sacraments, especially confession, which would absolve them of their sins. In the Bible, Paul reveals in Romans 10:17 “So faith comes from what is heard, and what is heard comes through the word of Christ.” (New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, Romans, Chapter 10, Verse 17). This type of message alienated Deaf people from collective worship and their religious community and insinuated that without the ability to hear or speak, they could not receive salvation in this life or the next (2).

Illustrated Confessory Manuscript: A Way to Confession and Absolution

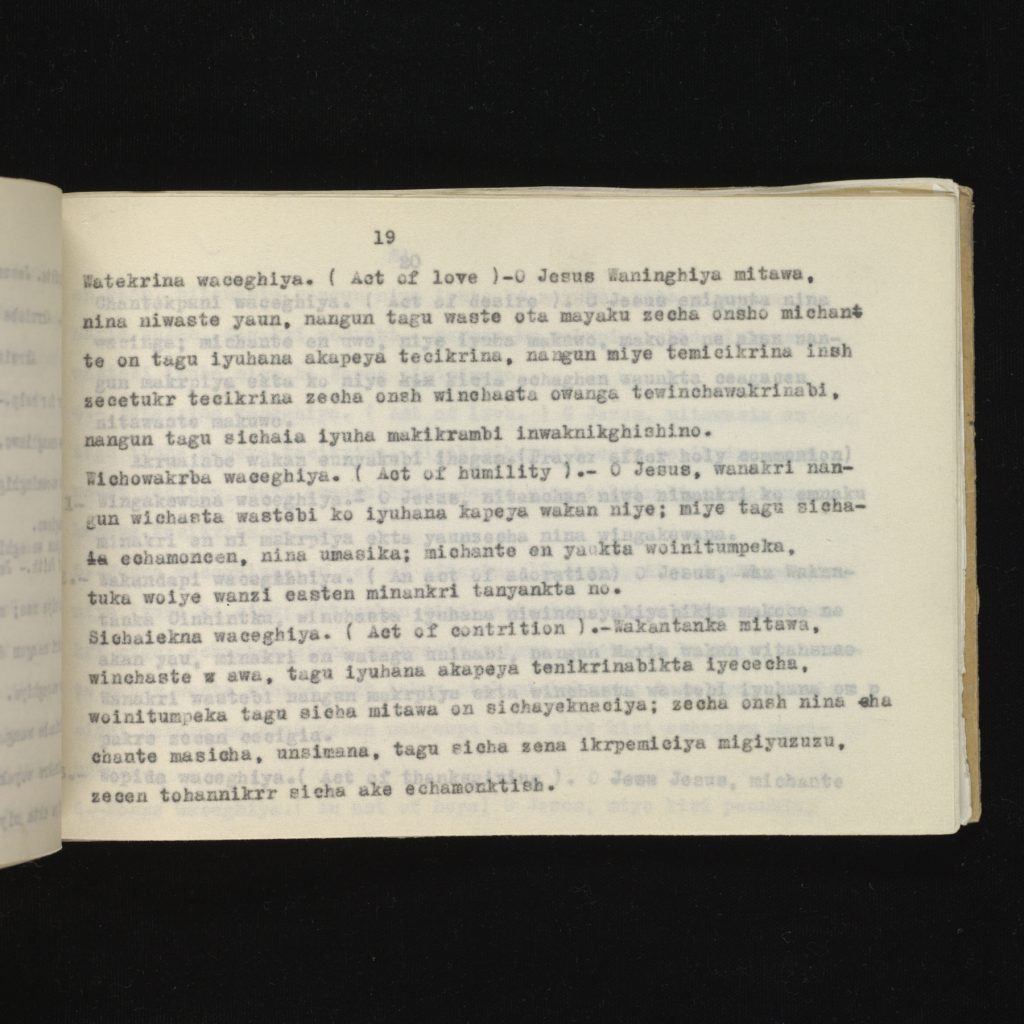

The manuscript is composed of ninety-two leaves, with ten leaves left blank (possibly to leave room for sins yet to be illustrated). It contains two sets of drawings composed by different hands: the first set illustrated in black and white featuring a man and Latin captions, and the second in color picturing women with captions in Dutch.

The first set includes thirty-six drawings of sins with a man as the subject, completed in pen and ink with pale washes of black and gray.

The second series includes forty-six drawings of similar sins with women as the subjects, done in iron-gall ink and colored with gouache and watercolor.

Priests and Deaf Educators

In 1519, Protestant reformer Martin Luther (1483–1546) addressed the theological question of how Deaf people could hear God by turning to the teachings of Saint Jerome (347–420 BC), the patron saint of translators and librarians. Saint Jerome recognized Deaf people as God’s children. He said, “…to the word of God nothing is ‘deaf’ if only the inward ‘ears’ are willing to hear.” The answer for Jerome (and later, Martin Luther) lay in the figurative ears of the soul: “Whosoever has these,” Jerome wrote, “will not need physical ears to apprehend the Gospel of Christ.” In one of his sermons on Galatians, Martin Luther expanded upon Jerome’s reasoning: “…the word of God is not heard even among adults and those who hear, unless the Spirit promotes growth inwardly.” (2)

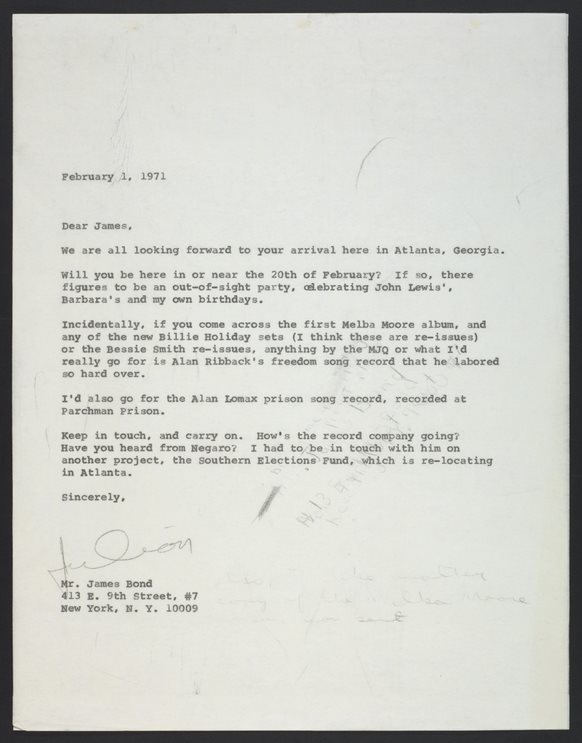

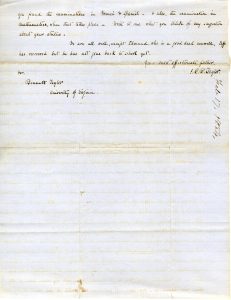

In the 1670s, the French Franciscan friar Christophe Leutbrewer created a confessory manual that featured definitions of sins that were printed on pre-cut paper. This allowed Christians who were Deaf to pull the slips up individually so that they extended over the paper margin, thereby serving as topical reminders for reflection and confession, which could be tucked under the margin again after the confession (3) (4)

Christophe Leutbrewer’s confessory book, with sins defined and printed on pre-cut paper, Leutbrewer, Christophe, “BRB1072,” https://bridwell.omeka.net/items/show/1693.

Hand Gestures and Sign Language (vs. Oralism)

French abbot Charles-Michel de L’Épée (1712-–1789), was the founder of the first free public school for deaf children in the world, the National Institute for Deaf Children of Paris (5). In 1755, he demonstrated that Deaf people could communicate among themselves and with the hearing world through a system of conventional gestures, hand signs, and finger spelling, much like modern French Sign Language. Following L’Épée’s work, there were other educators and theologians, including Roch Ambroise Cucurron Sicard, principal of L’Épée’s school after his death (6), Roch Ambrose Auguste Bébian, who was fluent in sign language (7), Laurent Clerc, a French man who was the first Deaf teacher of Deaf students and taught in America (8), Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, who started the first Deaf school in America (9), and Jean Massieu, a Deaf person who taught Deaf children and formalized French Sign language (10). These educators fought for Deaf people to have their own language of hand signs and were opposed to the teaching method of Oralism, which banned sign language and tried to force Deaf people to conform by making them use lipreading or oral speech. Oralism was an oppressive method, as it infringed on deaf peoples’ ability to use their own language—sign language. Instead of bringing hearing and non-hearing people together, Oralism hindered Deaf people and stripped them of their identity, culture, and community (11).

In 1817, Roch Ambrose Auguste Bébian (1789–1839), the author of an important book of sign language titled Mimographie, wrote, “We do not speak, it is true; but still do you think us unable to express ourselves as well with our eyes, our hands, our smiles, our lips? Our most beautiful discourse is at the tips of our fingers, and our language is rich in secret beauties that you who speak will never know. And have we not our own art of Phoenicia to paint the words that speak into our eyes?” Bébian points out that Deaf people and their use of sign language are resilient. They can see the world more visually and have a sharper focus on communication and listening which gives them a unique and valuable perspective.

In 1850, French author and political activist Victor Hugo (1882–1885) wrote to his close friend, Deaf educator Ferdinand Berthier, who was a student of Bébian and a recipient of the French Legion of Honor for his activism of Deaf peoples’ linguistic rights. Hugo wrote, “You, Sir, who have the rare talent of being at once [Deaf] and eloquent, please tell your friends . . . that in my eyes the accession of the [Deaf] to civic and intellectual life must be counted among the most magnificent and decisive accomplishments in the history of the progress of humanity.” Hugo added, “What matters deafness of the ear, when the mind hears? The only deafness, the true deafness, the incurable deafness, is that of the mind.” Hugo’s message embraces the concept that Deaf people and those with hearing loss can see the world more visually, and have a sharper focus on communication and listening. They can thrive in a hearing-centric world by using other means of communication, embracing new ideas, and accepting different approaches, which can lead to more inclusive engagement with the world (12).

Honor and Awareness of Deaf persons and their Culture

Today, Deaf culture is a vibrant and diverse community that spans the globe. Deaf people have their own unique language, customs, and traditions and are proud of their identity and heritage. From Deaf artists and musicians to Deaf athletes and entrepreneurs, people who are Deaf continue to make important contributions to society and to shape the world around them (13).

Despite these gains, however, there is still much work to be done to fully recognize and honor the contributions of the Deaf community (13). Collections like this manuscript mark a beginning in sharing more materials that include Deaf people. Similar to this acquisition is a manuscript titled Emblems on Christian Doctrine for use by Deaf People (MSS 16804) [Emblemi sulla Dottrina Cristiana ad uso de’ Sordo-Muti Ottavio Giovanni Battista Assarotti (1753–1829), which is another recent addition that represents the identity of Deaf persons in our collections and community.

Deaf Awareness Month, which is celebrated in September, provides an important opportunity to learn more about the history, culture, and achievements of the Deaf community. The Community Services for the Deaf (CSD) website states, “Deaf history is a testament to the strength and resilience of the human spirit. Despite centuries of discrimination and marginalization, Deaf people have persevered and created a culture that is vibrant, unique, and enduring. By celebrating Deaf history and culture, we can honor the contributions of Deaf people and promote a more inclusive and compassionate world for all” (13).

Ways to support Deaf Awareness

- Watch Deaf films and documentaries, such as 2021 film CODA by Sean Hader, 2009 film See What I’m Saying by Kaycee Choi, and 2023 film The Hammer about wrestler Matt Hammil

- Read books by Deaf authors or that accurately depict Deaf character

- Support Deaf-owned businesses in your area

- Learn Sign Languages

- Donate to organizations that advocate for the deaf community

- Advocate for improved accessibility, education, and workplace protections for deaf people

- Listen to and share the stories of Deaf creators

Sources:

- Gannon, Jack, R. “Deaf Heritage: A Narrative History of Deaf America.” Gallaudet Classics in Deaf Studies Series, Volume 7, June 30, 2012

- Oates, Rosamund. “Speaking in Hands: Early Modern Preaching and Signed Languages for the Deaf.” Past and Present. Oxford Academic. Volume 256, Issue 1, August 2022, Pages 49–85 Accessed 7/24/23

- Smyth, Adam. “Slicing the Page: Christophe Leutbrewer and Raymond Queneau” Text! April 22, 2022.

- Leutbrewer, Christoph. “BRB1072,” Bridwell Library Special Collections Exhibitions, Southern Methodist University. accessed September 19, 2023,

- “Charles-Michel de l’Épée.” Wikipedia. Accessed 9/19/23

- “Roch Ambrose Cucurron Sicard.” Wikipedia. Accessed 9/19/23

- “Roch-Ambroise Auguste Bébian.” Wikipedia. Accessed 9/19/23

- “Louis Laurent Marie Clerc.” Wikipedia. Accessed 9/19/23

- “Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet” Wikipedia. Accessed 9/19/23

- “Jean Massieu.” Wikipedia. Accessed 9/19/23

- “Oralism.” Wikipedia. Accessed 9/19/23

- The Mind Hears Mission Statement, a blog by and for deaf and hard of hearing academics. The Mind Hears website. Accessed 9/19/23

- Community Services for the Deaf (CSD) website. “Exploring the Rich Heritage of Deaf People.” Accessed 7/24/23