Content Warning Note: The blog about this collection contains racial terminology and imagery typical for the time that contemporary viewers may find offensive. The purpose of this note is to give users the opportunity to decide whether they need or want to view these materials, or at least, to mentally or emotionally prepare themselves to view the materials.

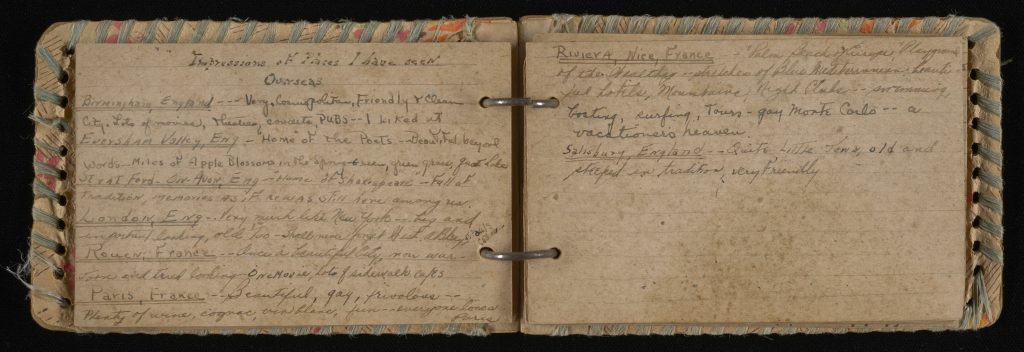

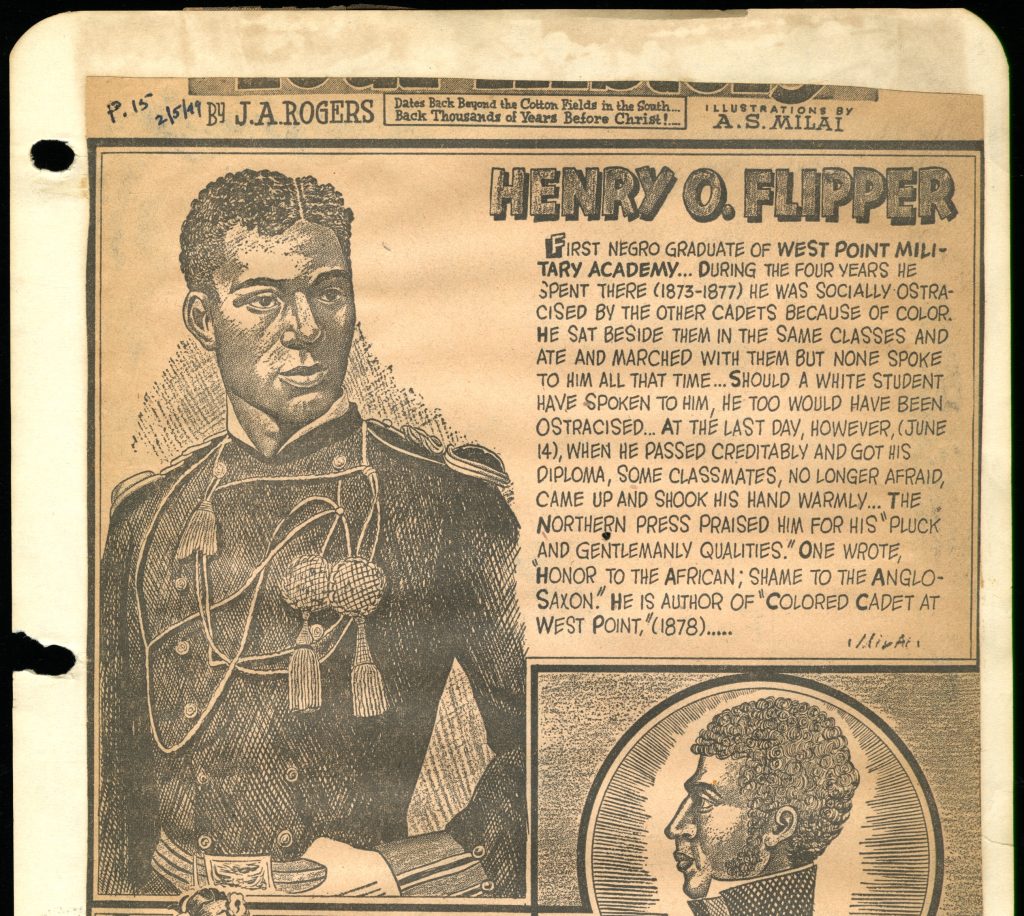

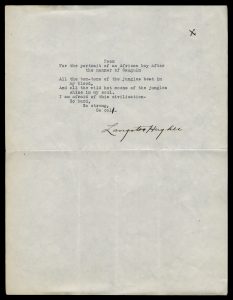

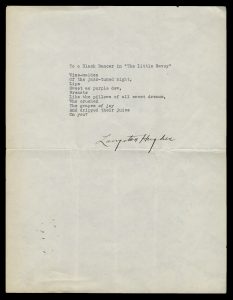

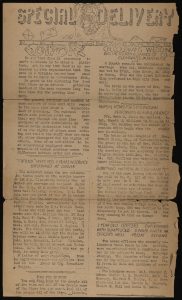

This post by Manuscripts and Archives Processor Ellen Welch introduces a recent acquisition: a scrapbook labeled “Negro History” (MSS 16835) compiled by Bernard Proctor, a celebrated World War II captain in the Tuskegee Airmen and a descendant of the West Indies. (See this oral history video series by the Visionary Project for more about Proctor and his life.) The scrapbook consists of cartoons detailing historical vignettes about Black history from a weekly newspaper series—”Your History” published by the Pittsburgh Courier, an African American newspaper and edited by Robert L. Vann. The series was written by Jamaican American journalist Joel Augustus Rogers (1880-1966) and illustrated by Samuel Milai during the years 1940-1950 and then by George Lee from 1934-1937. Proctor collected, cut out, and pasted the cartoons on paper and placed them in a 3-ring binder. The series in this archive includes the dates 1948-1950; the newspaper ran the series from 1934-1966.

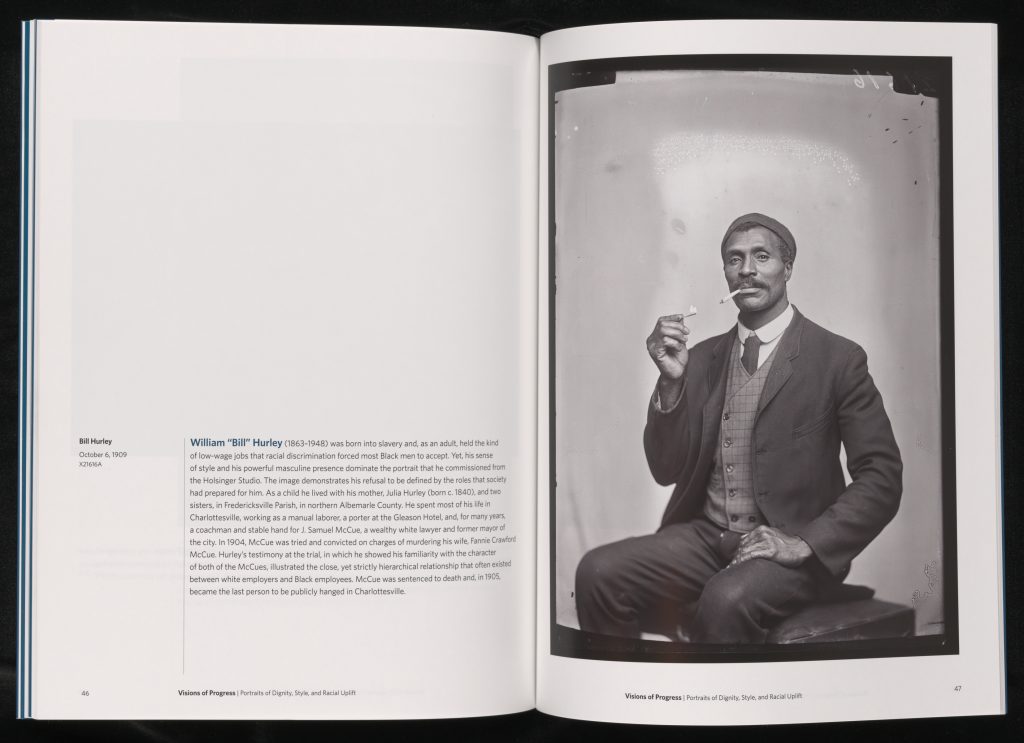

While working as a Pullman porter in Chicago, Joel Augustus Rogers travelled across the country before he launched his career as one of the leading Black journalists of his generation. [1] He wrote regularly for many newspapers including the Pittsburgh Courier (1921-1966) and the New York Amsterdam News (1920-1935). Moving to New York in 1921, Rogers wrote and published at least sixteen different books and pamphlets, “a significant body of work that covered the global African community from ancient to modern times and the diaspora.” [2]

Dr. William E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963), a scholar in American history, wrote, “No man living has revealed so many important facts about the Negro race as has Rogers. He traveled to sixty different nations, studying civilizations, highlighting achievements of ethnic Africans, and challenging prevailing ideas about the social construction of race.” [2, 3]

The illustrations and descriptive texts in “Your History” span the history and achievements of Black figures in many key events, such as the birth of Buddha, the birth of Christ, the United States Civil War, Antebellum, and American Reconstruction. Rogers states that Black people were rulers of Africa and were revered as Gods (before the transatlantic slave trade began in the sixteenth century). His historical vignettes are mostly true facts, but some are embellished because he used extremes to counter the severe racism embedded in Western culture. The text of Rogers’s cartoons frequently begins with superlatives like “one of the most honored,” “one of the best known,” “one of the greatest,” or “one of the first.” Scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. asserts, “J. A. Rogers was as serious a researcher as they come, as serious as W.E.B. Du Bois and Carter G. Woodson.” He explained that, even though Rogers embellished some of the stories, he raised questions that would stimulate other researchers to dig deeper into Black history. [3] Gates characterized Rogers’s work as an invaluable resource:

“[Rogers was] a major—in many cases the only—source for the ordinary Black person to learn of their history from the 1920s through the ’70s. They certainly did not get it in their schools and universities or find out about it in mainstream newspapers and books. Rogers brought the idea of Black history to the fore, maintaining that the conventional scholars had a blind spot…” [4]

The series depicts Black men and women as leaders of every field: doctors, nurses, preachers, teachers, lawyers, property owners, politicians, planters, farmers, athletes (Olympians), artists, scientists, mathematicians, archeologists, dentists, musicians, and astronomers. The historical vignettes are patterned after Robert Ripley’s “Believe it Or Not” style of cartoons. They are brief, easy to read, and designed to capture attention.

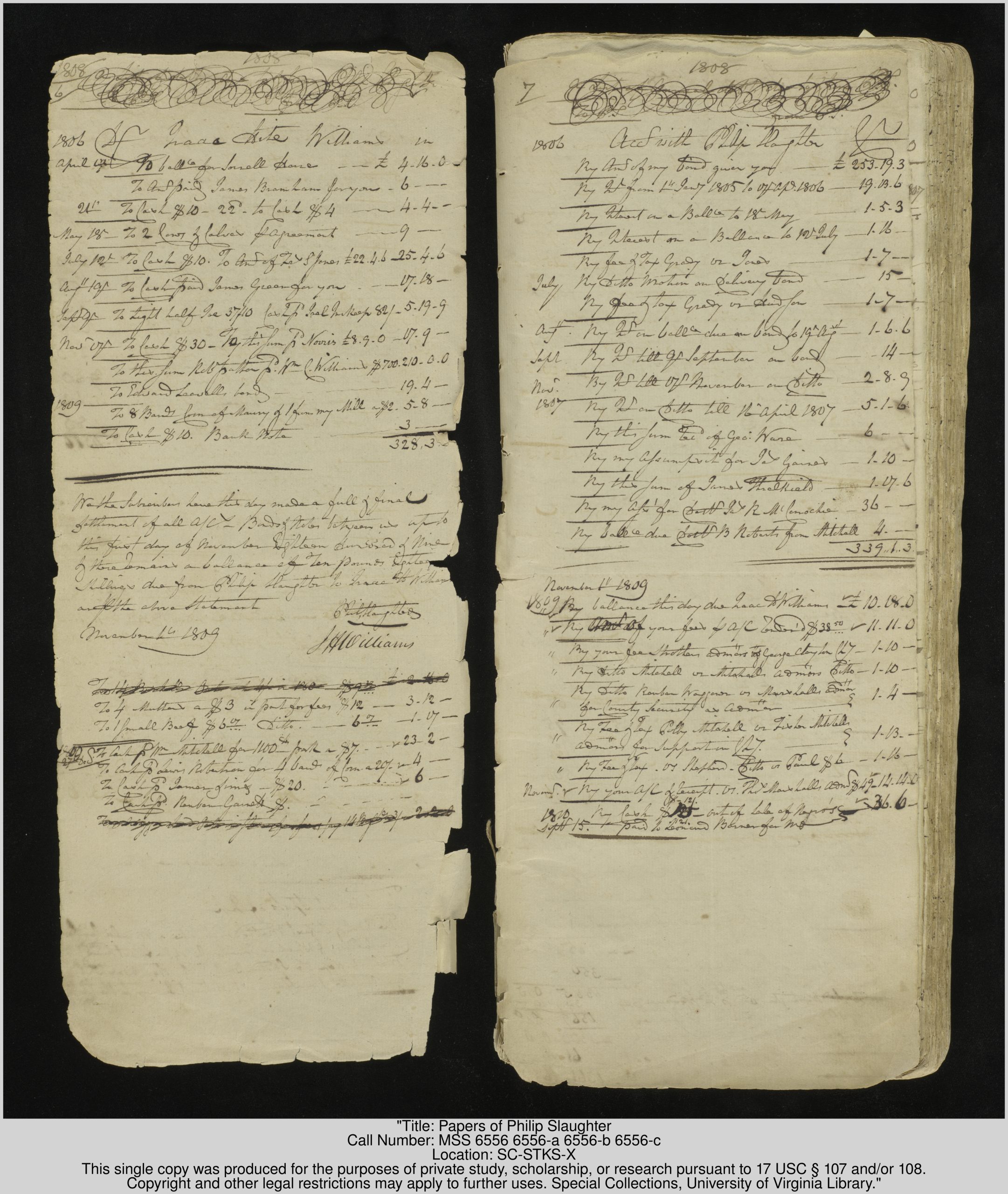

Included in the collection are articles from the Chicago Defender about Black people in history and another series written in the Pittsburgh Courier by James M. Rosbrow (also illustrated by Samuel Milai) titled “Negroes in the Halls of Congress.” This column is about Black men who were born into enslavement and became United States senators and congressmen in the Republican Party during Reconstruction (1865-1877). They championed legislation to further civil rights and improve conditions for Indigenous people until the southern white Democrats regained their political platforms and ousted them. However, their efforts greatly contributed to the civil rights movement by establishing racial equality and citizenship in the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments.

This description of the Pittsburgh Courier characterizes the importance of this archive:

“Through thirty years of persistence, Vann’s paper ultimately helped change the moral tone of American race relations for future generations. Dozens of editorial campaigns and thousands of newspaper articles, features, and cartoons slowly chipped away at the edifice of white supremacy and affected the way people discussed race, rights, and human dignity. This collective effort pushed multiculturalism closer to the mainstream of American political culture outside the South and helped make possible the formation of powerful interracial coalitions during the civil rights years.” [5]

Explore some of Rogers’s cartoons in the collection below. There are hundreds more of the cartoons, too many to mention and yet too fascinating to omit. This archive is a must see! In the words of Dr. John Henrik Clarke (1915–1998), a prominent African American historian, professor, and pioneer in Afrocentrism and Pan-African studies, Rogers “looked at the history of people of African origin and showed how their history is an inseparable part of the history of mankind.” [2]

“Elizabeth Keckley” transcription

Elizabeth Keckley (1818-1907). One of the ablest women, though but an employee, who ever lived in the White House. Closest friend and confidante of Mary Todd, wife of Abraham Lincoln, She had been born a slave and had bought her freedom. A skilled dressmaker, she had worked in the South for Jefferson Davis and coming to Washingtonshe worked for rich families until she came to Mrs. Lincoln, who became extremely attached to her. She was tall, stately, cultured, one writer said, “She would have been an outstanding personality at the court of Louis XIV.” Her book, “Behind the Scenes,” dealing principally with Mrs. Lincoln, was the literary sensation of 1868. Later, she taught domestic science at Wilberforce University and prepared the Negro exhibit for the Columbian Exposition…….

Keckley wrote a popular book about her experiences with Mary Todd Lincoln at the White House, featuring anecdotes such as the one below:

“In 1863 the Confederates were flushed with victory, and sometimes it looked as if the proud flag of the Union, the glorious old Stars and Stripes, must yield half its nationality to the tri-barred flag that floated grandly over long columns of gray. These were sad, anxious days to Mr. Lincoln, and those who saw the man in privacy only could tell how much he suffered. One day he came into the room where I was fitting a dress on Mrs. Lincoln. His step wasslow and heavy, and his face sad. Like a tired child he threw himself upon a sofa and shaded his eyes with his hands. He was a complete picture of dejection. Mrs. Lincoln, observing his troubled look, asked:

“Where have you been, father!”

“To the War Department,” was the brief, almost sullen answer,

” Any news!”

“Yes, plenty of news, but no good news. It is dark, dark everywhere.”

— Excerpt from Elizabeth Keckley, Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House (New York: G.W. Carleton & Co, 1868). (A1868.K42)

“Africa” transcription

Africa: Mother of Western Culture… Home of religion, medicine, art, science, and music… First to discover and use iron. Its temples, pyramids, and wealth of its pharoahsuneclipsed after 5000 years. Led in world culture for the first 6000 years … Its people invaded Europe several times improving it … They also contributed immensely to the development of nearly all the countries of the New World. Africa is today the world’s greatest region of untapped wealth … (This reproduction is from a drawing of the Middle Ages.)

“Henry O. Flipper” transcription

Henry O. Flipper. First Negro graduate of West Point Military Academy… During the four years he spent there (1873-1877) he was socially ostracised [sic] by the other cadets because of color. He sat beside them in the same classes and ate and marched with them, but none spoke to him all that time… Should a white student have spoken to him, he too would have been ostracised [sic] … At the last day, however, (June 14), when he passed creditably and got his diploma, some classmates, no longer afraid, came up and shook his hand warmly… The Northern Press praised him for his “pluck and gentlemanly qualities.” One wrote, “Honor to the African; shame to the Anglo-Saxon.” He is the author of “Colored Cadet at Westpoint,” (1878).

Excerpt from Henry Ossian Flipper, The Colored Cadet at West Point: Autobiography of Lieut. Henry Ossian Flipper, U. S. A., First Graduate of Color From the U. S. Military Academy (New York: Lee, 1878). (U410.P1 F6 1878):

CHAPTER X: TREATMENT

“A brave and honorable and courteous man

Will not insult me; and none other can.”—Cowper.“How do they treat you?” “How do you get along?” and multitudes of analogous questions have been asked me over and over again. Many have asked them for mere curiosity’s sake, and to all such my answers have been as short and abrupt as was consistent with common politeness. I have observed that it is this class of people who start rumors, sometimes harmless, but more often the cause of needless trouble and ill-feeling. I have considered such a class dangerous, and have therefore avoided them as much as it was possible. I will mention a single instance where such danger has been made manifest.

A Democratic newspaper, published I know not where, in summing up the faults of the Republican party, took occasion to advert to West Point. It asserted in bold characters that I had stolen a number of articles from two cadets, had by them been detected in the very act, had been seen by several other cadets who had been summoned for the purpose that they might testify against me, had been reported to the proper authorities, the affair had been thoroughly investigated by them, my guilt established beyond the possibility of doubt, and yet my accusers had actually been dismissed while I was retained.* This is cited as an example of Republican rule; and the writer had the effrontery to ask, “How long shall such things be?” I did not reply to it then, nor do I intend to do so now. Such assertions from such sources need no replies. I merely mention the incident to show how wholly given to party prejudices some men can be. They seem to have no thought of right and justice, but favor whatever promotes the aims and interests of their own party, a party not Democratic but hellish.

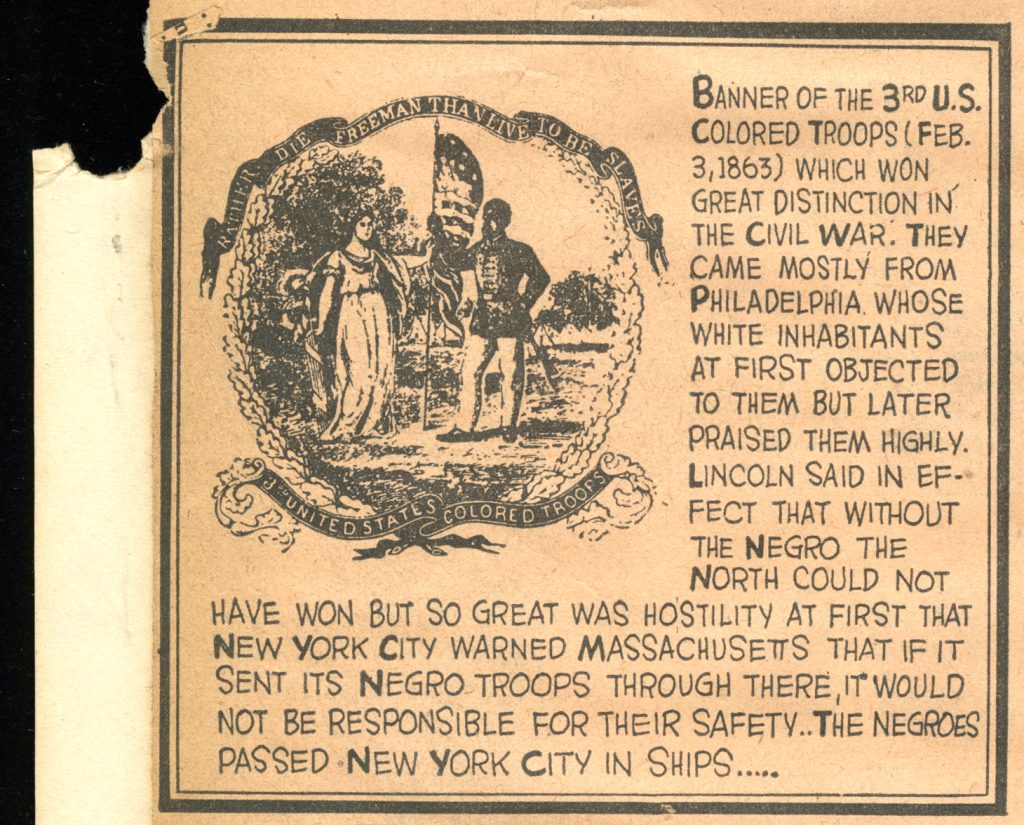

“Banner of the 3rd U.S. Colored Troops” transcription

Banner of the 3rd U.S. Colored troops (Feb. 3, 1863) which won great distinction in the Civil War. They came mostly from Philadelphia whose white inhabitants at first objected to them but later praised them highly. Lincoln said in effectthat without the Negro the North could not have won but so great was hostility at first that New York City warned Massachusetts that if it sent its Negro troops through there, it would not be responsible for their safety…The Negroes passed New York City in ships…..

“Alfred Wood” transcription

Alfred Wood (Old Alf), of the 3rd U.S. Colored Cavalry was one of the greatest scouts of the Union Army in the Civil War… Was of mixed Negro, white and Indian stock..Operated chiefly around Vicksburg, Miss… Once, captured, he imitated so well the talk and manner of a plantation slave, that when he claimed he had shot a union soldier and was running away, he was allowed to go… Thanks to his light skin and long hair, he once joined the TexasRangers and learnt their plans… He is credited with withmuch of the success of the Union Army in Mississippi…..

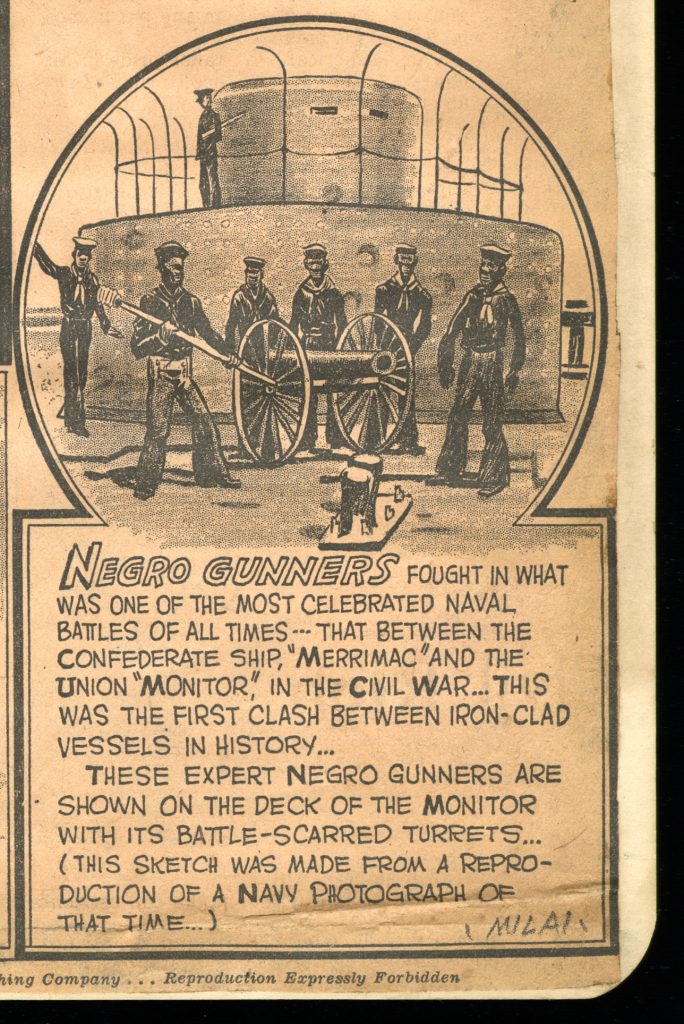

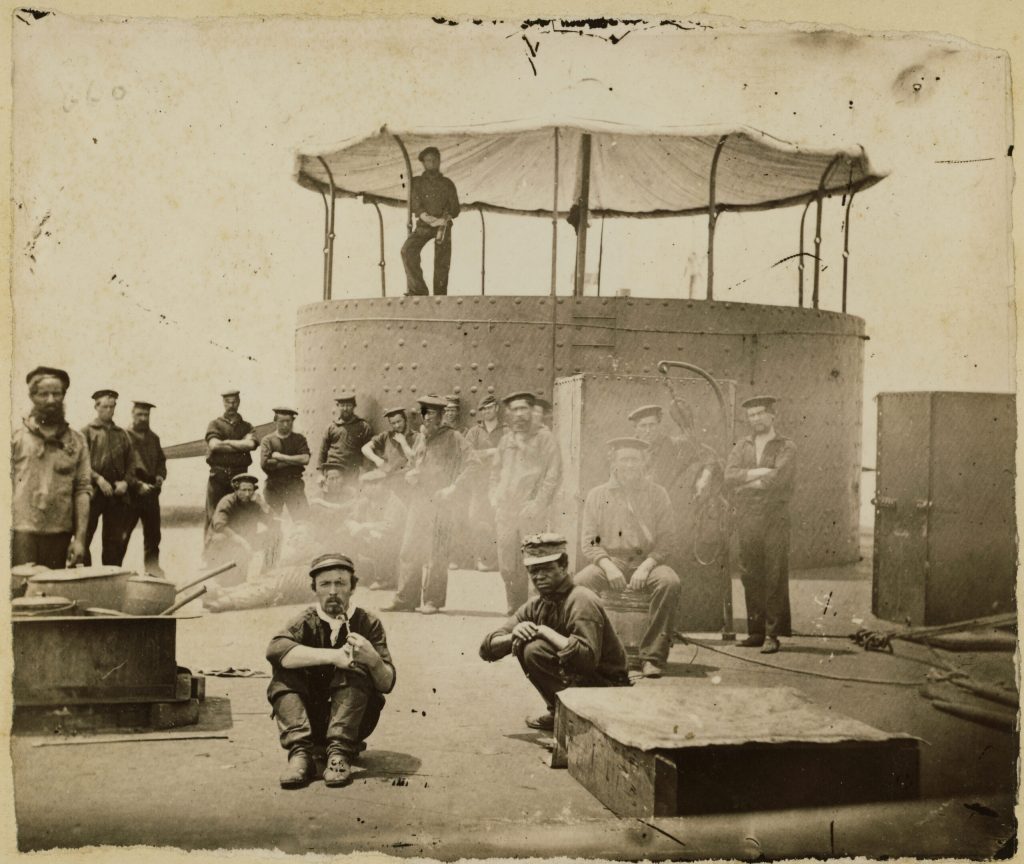

“Negro Gunners” transcription

Negro Gunners fought in what was one of the most celebrated naval battles of all times—that between the Confederate ship, “Merrimac” and the Union “Monitor” in the Civil War… This was the first clash between iron-clad vessels in history…These expert Negro gunners are shown on the deck of the monitor with its battle-scarred turrets… (This sketch was made from a reproduction of a navy photograph of that time…)

“Les Pionieers Noirs” transcription

Les Pionniers Noirs, or Black pioneers, was one of Napoleon’s crack Negro regiments… They fought in the great battles of the Napoleonic Wars. In Italy they served under Victor Hugo’sfather and captured Fra Diavolo… Another famous regiment was Corps d’ Afrique, which was mounted … Negro soldiers were also in the white regiments as privates and officers, the most famous of which was General Dumas, commander of all cavalry, white and Black … ( Sketched from a drawing of a Black pioneer in a print dated 1803.)

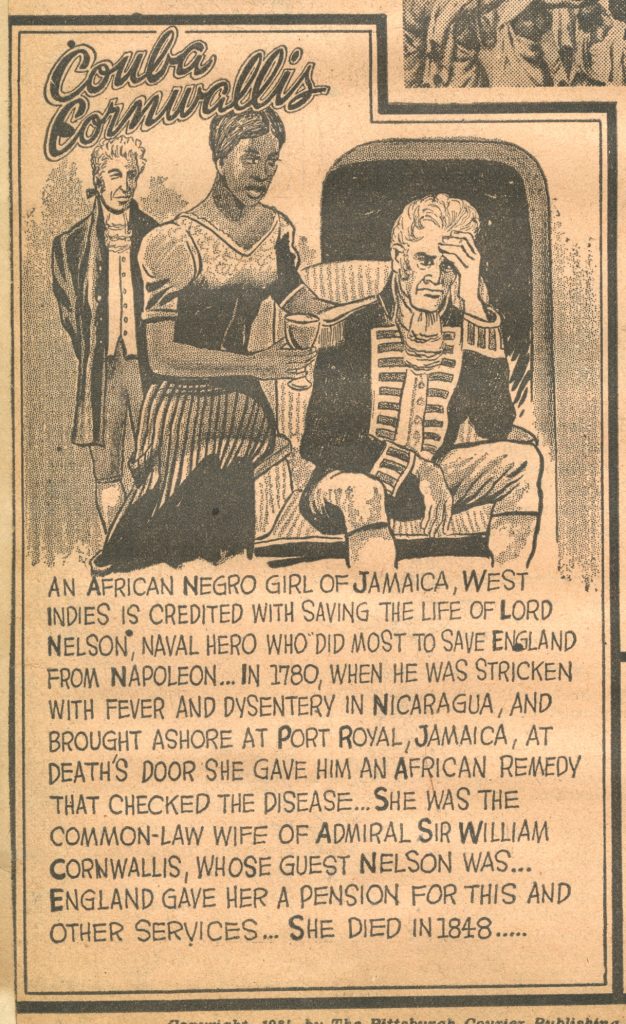

“Couba Cornwallis” transcription

An African Negro girl of Jamaica, West Indies is credited with saving the life of Lord Nelson, naval hero who did most to save England from Napoleon… In 1780, when he was stricken with fever and dysentery in Nicaragua, and brought ashore at Port Royal, Jamaica, at death’s door she gave him an African remedy that checked the disease… She was the common-law wife of Admiral Sir William Cornwallis, whose guest Nelson was…England gave her a pension for this and other services… She died in 1848…

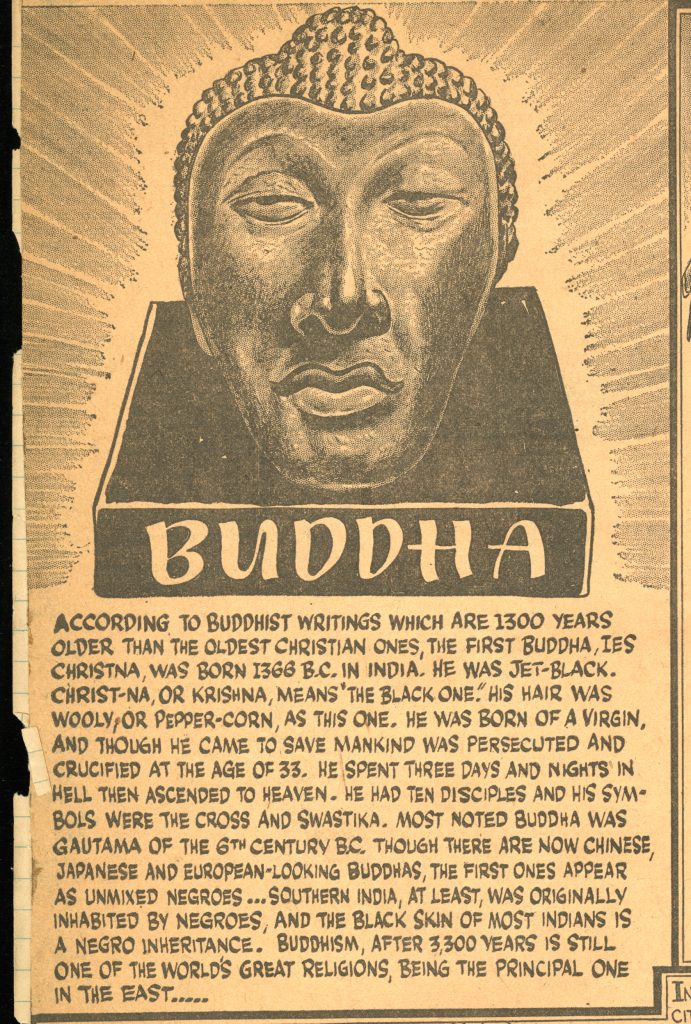

“Buddha” transcription

According to Buddhist writings which are 1300 years older than the oldest Christian ones, the first Buddha, Ies Christna, was born 1366 B.C. in India. He was jet-Black. Christ-na, or Krishna, means “the Black one.” His hair was woolly, or peppercorn, like this one. He was born of a virgin, and though he came to save mankind, he was persecuted and crucified at the age of 33. He spent three days and nights in hell then ascended to heaven. He had ten disciples, and his symbols were the cross and swastika. Most noted Buddha was Gautama of the 6th century B.C. Though there are now Chinese, Japanese and European-looking Buddhas, the first ones appear as unmixed negroes … Southern India, at least, was originally inhabited by Negroes, and the black skin of most Indians is a Negro inheritance. Buddhism, after 3,300 years is still one of the world’s great religions, being the principal one in the East….

“Balthasar” transcription

Transcription: Balthasar, one of the Three Wise Men from the East said to have been at the “Birth of Christ.” The wise men not only came from the East,but the legend originated there … The first Christ was born in India about 1366 B.C. He is described as “coal black, wooly haired.” ……. A later Indian Christ born 1330 B.C. was also coal-black, wooly-haired, and worshipped by wise men. He was crucified in his 33rd year. All Christs were Black, including the one worshipped by the West, until the whites rose to power and painted him as being white. The New World also had its Black Christs long before Columbus, the most famous being in Guatemala, which is still worshipped by the Indians … Originally there were probably no whites among the Wise Men, but white European painters made two of them white. Anatole France noted French writer [,] has a story in which a white queen falls in love with Balthasar. The legend of Christ throughout the Ages is intended to make man kindlier to his fellowman…… The subjects who posed for Balthasar were usually Negro favorites of kings, queens and great lords of Europe. These characters were sketched from a reproduction of a painting by Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516), the famous Flemish painter ….

“Slave” transcription

The word “slave” was originally applied to white people. It comes from “Slav” a Russian people captured by the Germans. —Milai—

Sources:

- Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross. Public Broadcasting Service 2013. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/j-a-rogers100-amazing-facts-about-the-negro/

- Rashedi, Runoko. “Critical Assessment of Joel Augustus Rogers” Global Presence 002 https://www.knarrative.com/gap002

- Gates, Henry, Louis, Jr. “Who Was Joel A. Rogers?” The Root. November 17, 2014. https://www.theroot.com/who-was-joel-a-rogers-1790877731

- Rogers, J.A. “J.A Rogers: Selected Writings” Edited by Louis J. Parascandola. The University of Tennessee Press. 2023. JSTOR https://www.jstor.org/stable/jj.9669490

- Cilli, Adam Lee. “The Pittsburgh Courier’s Discursive Power, 1910-1940” Black Perspective. African American Intellectual History Society. September 8, 2021. https://www.aaihs.org/the-pittsburgh-couriers-discursive-power-1910-1940/#fnref-234057-3

- Freeman, Jude. “Who Was Queen of Kingston Cubah Cornwallis?” Black History Month. October 25, 2018. https://iambirmingham.co.uk/2018/10/25/who-was-the-queen-of-kingston-cubah-cornwallis/

- Kramer, Kyra Cornelius. “The Amazing Life of Cuba Cornwallis” February 13, 2020. https://www.kyrackramer.com/2020/02/13/the-amazing-life-of-cuba-cornwallis/

- “Slave” Merriam Webster dictionary. Accessed 9/23/25. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/slave#:~:text=Slavic%20people%20were%20so%20frequently,then%20slave%20in%20Modern%20English.

- “Sainte Dominque” Wikipedia (Napoleon and Toussant L’Ouverture https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint-Domingue_expedition

- “3rd United States Colored Cavalry Regiment” Wikipedia. Accessed 9/23/25 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/3rd_United_States_Colored_Cavalry_Regiment

- Hubbell, John T. “Abraham Lincoln and the Recruitment of Black Soldiers” Volume 2, Issue 1, 1980 pp. 6-21. Journal of Abraham Lincoln Association. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/j/jala/2629860.0002.103/–abraham-lincoln-and-the-recruitment-of-black-soldiers?rgn=main;view=fulltext

- Main, Edwin M. “The Story of the Marches, Battles, and Incidents of the Third U.S. Colored Cavalry- A Fighting Regiment in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865″ Volume 2 1837. Free Download. Internet Archive. Louisville, Kentucky. Globe Print Company. 1908 https://archive.org/details/storyofmarchesba02main/page/38/mode/2up

- Fleming, Hannah. “Meet (a few) Monitor Crew” February 15, 2017. The Mariners Museum and Park. https://www.marinersmuseum.org/2017/02/meet-monitor-crew/

- Reidy, Joseph. “Black Men in Navy Blue During the Civil War” Fall 2001, Volume 33, No. 3. Prologue Magazine. National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2001/fall/black-sailors

- “Elizabeth Keckley” National Women’s History Museum. 2021 https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/elizabeth-keckley

- O’Gan, Patri. “Duty, Honor, Country: Breaking Racial Barriers at WestPoint and Beyond” National Museum of African American History & Culture. Smithsonian. https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/west-point

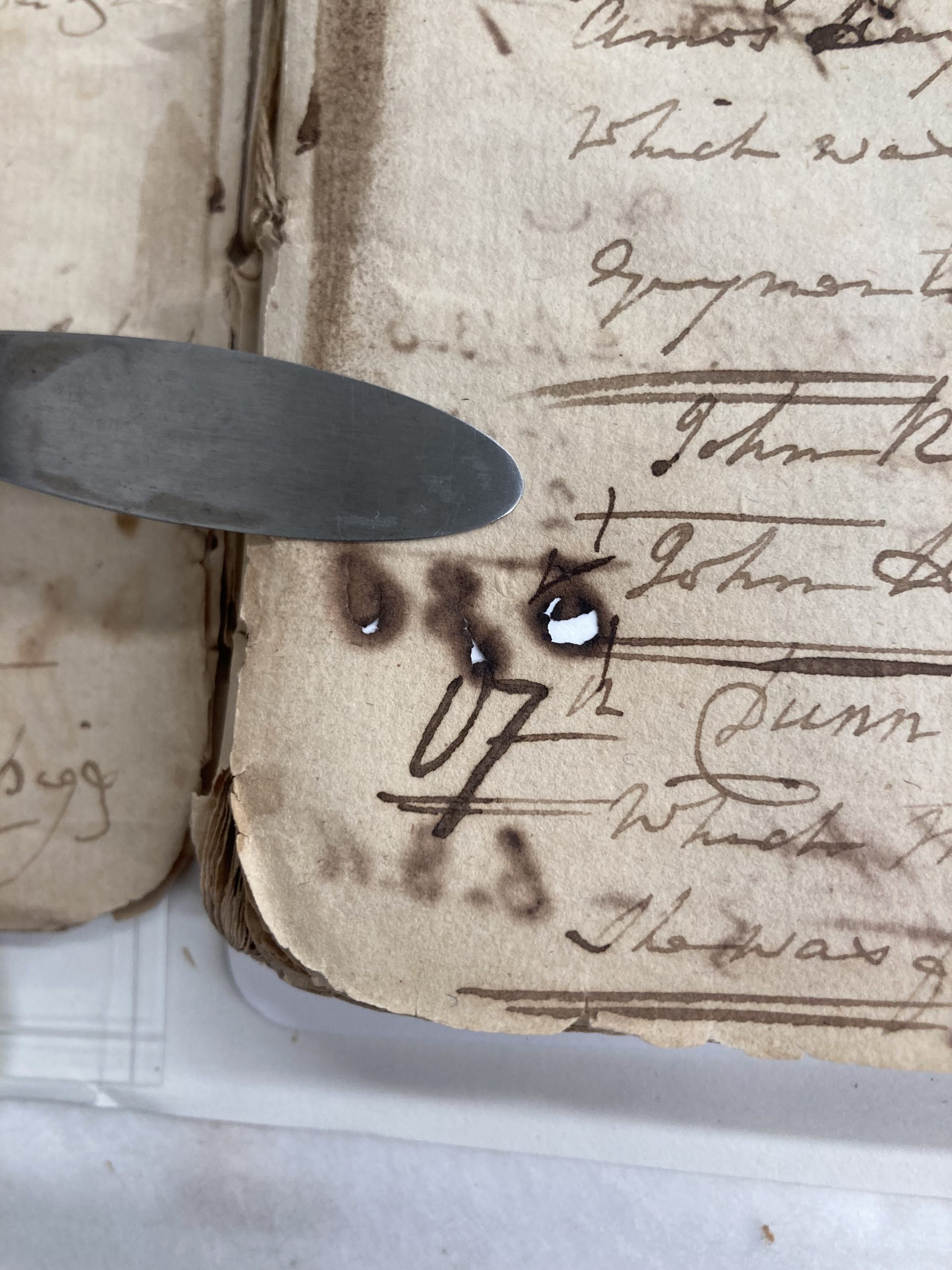

![March 17 and 18 diary entries with “Work[,] school[,] dull" written for each day.](https://smallnotes.library.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/000060287_0002-193x300.jpg)