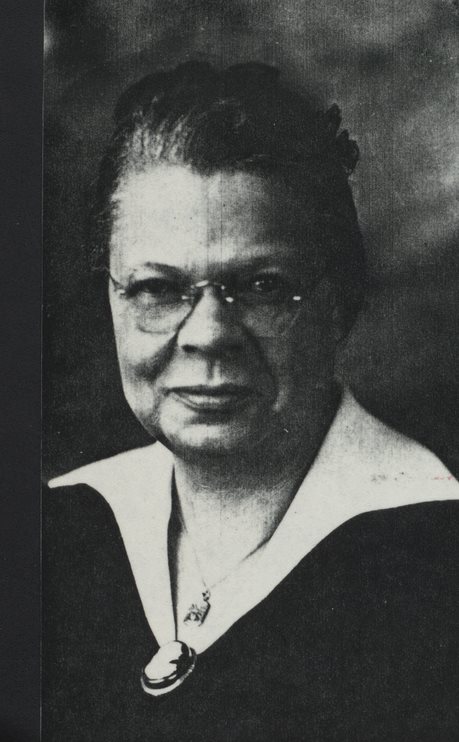

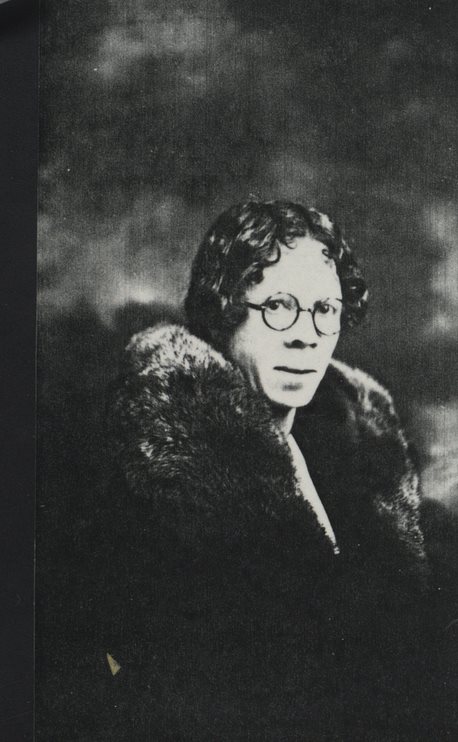

This post is contributed by Carlyn Ferrari, a William A. Elwood fellow in Civil Rights and African American Studies at the University of Virginia. She is an Assistant Professor of English at Seattle University and holds a PhD in Afro-American Studies. She specializes in twentieth-century African American literature and culture with a particular interest in Black women’s literary studies. In her research, she is interested in how Black women theorize the natural world and explores the relationship between Black feminist thought and literary ecocriticism. Her recent monograph about poet and civil rights activist Anne Spencer is entitled Do Not Separate Her from Her Garden and was published by the University of Virginia Press. After studying the Anne Spencer collection which is housed at the Small Special Collections Library, Ferrari writes about how she discovered more about the internal life of Anne Spencer, and her close association with the natural world.

I thought I knew who Anne Spencer (1882-1975) was before I visited the Papers of Anne Spencer and the Spencer Family. I knew she kept a literary salon during the New Negro Renaissance, and I wanted to write a cultural history about it. Like her fellow salon-keepers Georgia Douglas Johnson and A’Lelia Walker in Washington D.C. and Harlem, New York, respectively, Spencer’s salon-keeping is a form of Black women’s unrecognized, “invisible” labor, and I wanted to highlight this work. I approached her archival materials with a specific set of questions in mind: Who attended this salon? What took place during these gatherings? How often did people meet? What did people talk about?

I expected to find the answers to my questions, and I had tunnel vision.

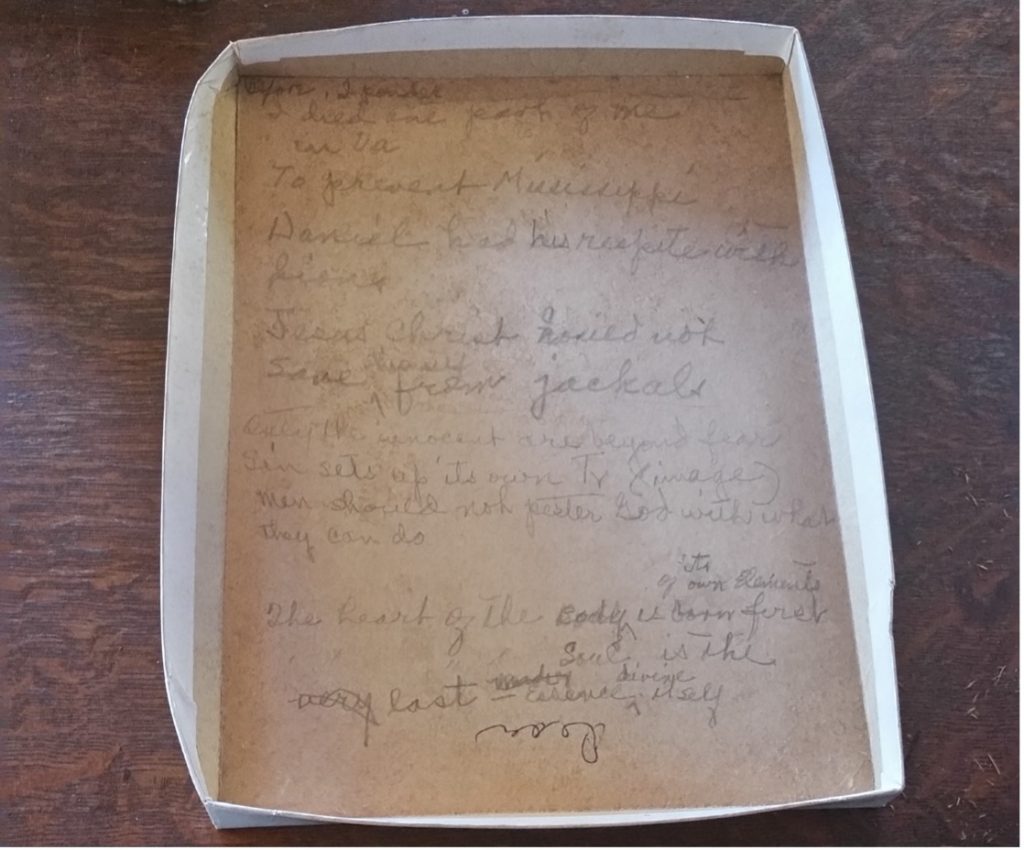

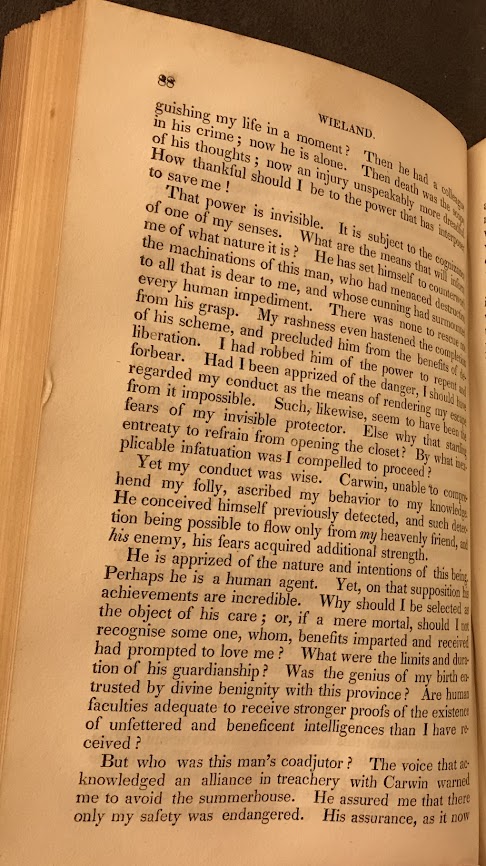

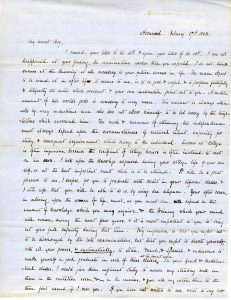

Once I started working with Spencer’s papers, everything I thought I knew, I quickly had to abandon. I did not find details about the innerworkings of her salon. (Although, thank-you letters from grateful houseguests confirmed that Spencer regularly entertained.) What I encountered were what I initially described as “scribblings”— drafted letters, notes, and poems written on scraps of paper and other surfaces, most of which were undated.

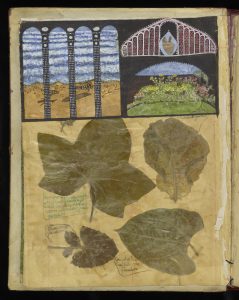

Spencer was quite innovative and found “homes” for her writings in the unlikeliest of spaces. This shoebox top is one of many examples of her creativity. (Personal photo taken at The Anne Spencer House & Garden Museum.)

And, initially, I was disappointed that I did not find what I was looking for.

I called my mother after a particularly frustrating day. OK, but what is there? She asked. Focus on that instead.

When I began to focus on what was present in her archival materials, I was immediately reminded of the questions that Alice Walker poses in In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens: “What did it mean for a Black woman to be an artist in our grandmothers’ time? In our great-grandmothers’ day?”[i]

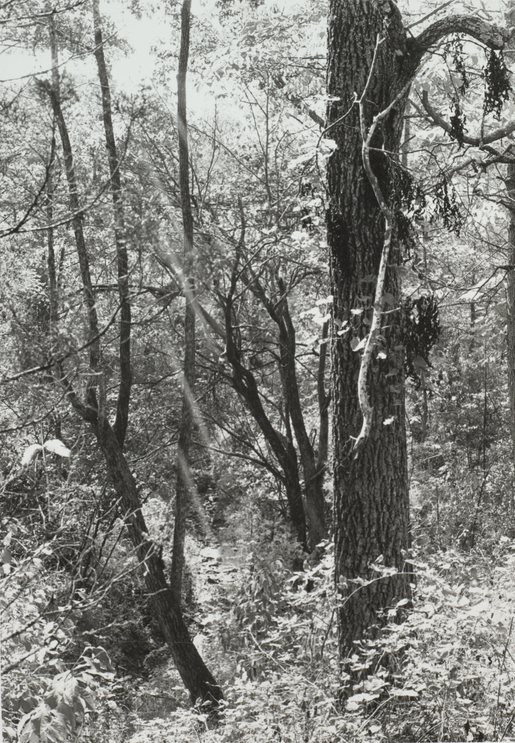

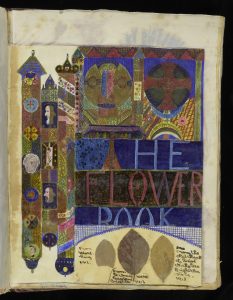

I came to understand that what I initially dismissed as meaningless “scribblings” were a part of Spencer’s artistry. Her writing on ephemera and other objects is her deliberate world-making, and I overlooked its significance. Afterall, she was a Black woman living in the Jim Crow South only one generation removed from slavery. Her unconventional writing practice is part of how she maintained what Alice Walker calls a “creative spark.”[ii] She wrote for herself, and publication was not the goal, which is understandable because critics often criticized her poetry for being raceless and apolitical because she often wrote about the natural world. But she did not change.

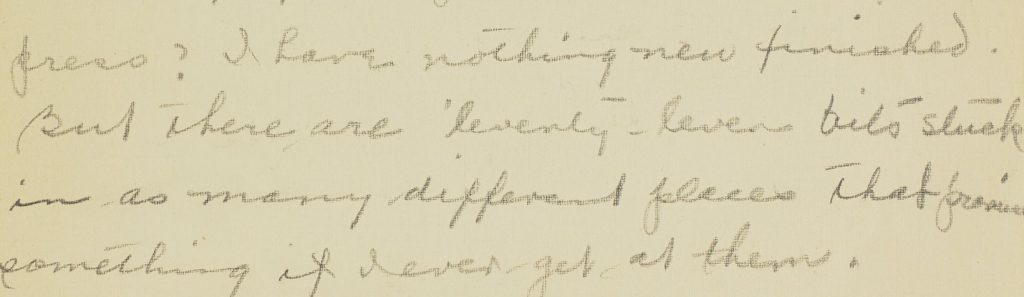

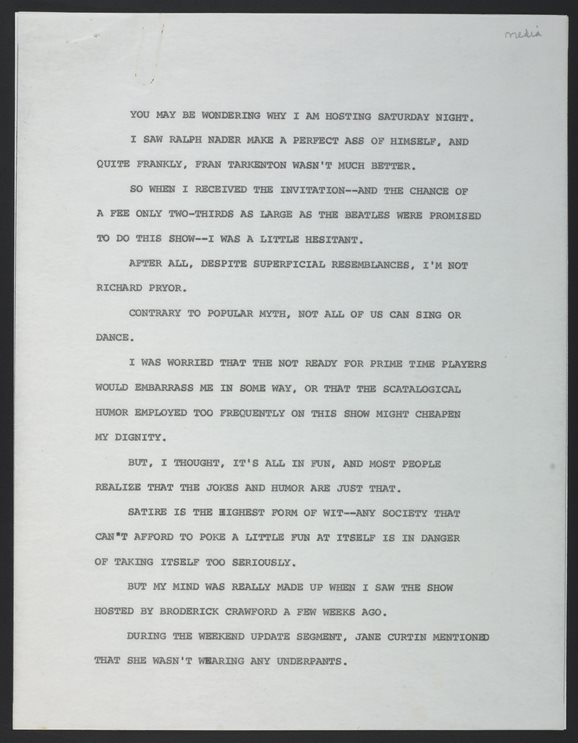

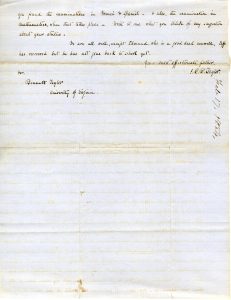

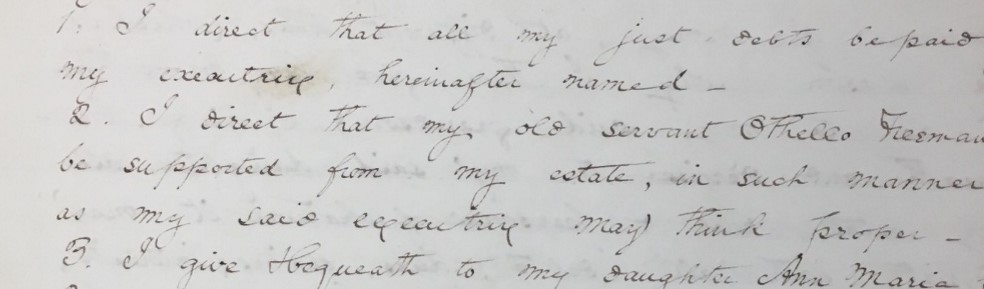

In this drafted letter to her friend, James Weldon Johnson, Spencer acknowledges her unique writing process, noting she has “‘leventy leven bits stuck in as many different places.” (Anne Spencer to James Weldon Johnson, October 20, 1921, on the back of a Johnson letter dated September 24, box 4, folder 7, Papers of Anne Spencer and the Spencer Family, 1829, 1864–2007, #14204, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville.)

In retrospect, I realize that I was treating Spencer’s archival materials like a phonebook directory: I expected to simply look up the information that I wanted and move on. But I am glad that they didn’t give me what I wanted because I learned more about Spencer than I anticipated, and I confronted the limitations of my narrow thinking. More importantly, I am glad that Spencer didn’t change and instead cultivated her artistry—her “creative spark”—in her own way.

[i] Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens, 233.

[ii] Walker, 240. Walker describes Black women’s creative spark as, “the seed of the flower they themselves never hoped to see: or like the sealed letter they could not plainly read.”

Cited Works

Walker, Alice. In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens. Orlando: Harcourt, 1983.

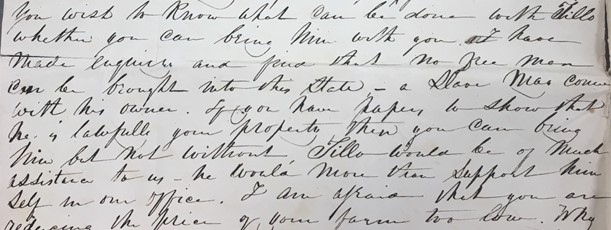

![Letter from William, who drove the carriage for Mr. Chalmers, to Anna Maria Mead Chalmers after Mr. Chalmers’s death. May 2, [1875]](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/William.jpg)