This post was contributed by Manuscript and Archives Processor Ellen Welch.

Introduction to the Herbert Friedman Holocaust Materials (MSS 16906)

The collection featured in this article, Herbert Friedman Holocaust Materials (MSS 16906), was donated by Herbert Friedman’s son, University of Virginia alumnus Mark Friedman, to the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library in 2024. The collection is centered on Herbert Friedman and his family in occupied Vienna before World War II. It includes family letters with descriptions of their life living apart, and in fear, with pleas for financial help and affidavits to help them leave Austria, as well as newspaper articles depicting Hitler’s greed and ephemera from their experiences. (The title of this blog post, “Lieber Herbert!”, comes from the salutation written on many letters from Herbert’s mother and other family and friends to thirteen-year-old Herbert after their family was separated.) The collection documents the desperation of one family under Nazi occupation from 1938 to 1940.

On March 12, 1938, German troops crossed the Austrian border unopposed, and, the following day, Austria was officially incorporated into Nazi Germany, including Vienna, the Friedmans’ hometown where they resided as Polish and Jewish immigrants. The Friedman family included Nusyn David Frdman/Friedman; his wife, Ida Muszkatblit Friedman; and their three children, Bernhard, Herbert and Lilli; along with Ida’s mother Golda Blatter Muszkatblit and Ida’s brother Bencjan Muszkatblit. After Vienna came under the Nazi rule, the Friedmans realized they were no longer safe in their home. By November 1938, the persecution of Jewish populations in Germany, Austria, and Poland forced the Friedman family’s exit from Vienna to scatter across France, Italy, Israel, Poland, England, and the United States to avoid arrest and deportation to a concentration camp.

David Friedman (Vater) and his eldest son, Bernhard, left Vienna on December 18, 1938, for America by borrowing money to travel by ship and live in Baltimore, Maryland, where they had relatives.Their hope was to bring the rest of the family over as soon as they could afford to send money and documentation. Shortly before the invasion, young Herbert, age 13, and his friend Ernst Fleisher, age 15, had jumped into the river in Vienna to save a drowning woman who tried to commit suicide. This brave action was reported by several Jewish newspapers and led to Herbert becoming a candidate for passage to England. He was one of the children slated for Kindertransport, a pre-World War II rescue mission (1938-1940) that brought nearly 10,000 predominantly Jewish children from Nazi-controlled territories to safety in Great Britain. He sailed with the children on December 10, 1938. None of his family were allowed to see him off, which, according to Herbert, was a terrifying experience that he remembered his entire life. During his two years in England, he attended numerous schools near and outside London, where he may have also resided; the majority were soon closed due to bombing by the German Luftwaffe.

Herbert’s life changed, and his childhood came to an end as he left his home to live in a foreign country that was bombed during World War II. His focus was on his own survival as well as helping his mother and younger sister escape Vienna. His grandmother (Omam) Golda Blatter Muszkatblit fled to France where she was briefly arrested and lived in Paris with other family members. Herbert’s mother, Ida Friedman, was left stranded in Vienna with her youngest daughter, Lilli. Ida tried for almost a year to join her husband David and eldest son Bernhard, who were learning English and working low paying jobs as tailors and shoemakers in Baltimore. They hardly made enough money to bring Ida or anyone else to America, and Ida could not get an affidavit or money to leave. She was frantic that, after barely surviving the First World War, she would be left alone in Austria during another war and would not be able to survive it. For eight terrifying months, no one could help her to get the right paperwork to leave. She was feeling desperate to get herself and Lilli to safety in the United States before the Gestapo could knock on her door and deport them to a concentration camp, at any moment, day or night.

With the help of many benefactors including Dr. Alvin and Fannie Thalheimer, Julie Myers Strauss, the National Refugee Service, the Baltimore Section National Council of Jewish Women, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, and the Refugee Children’s Movement, Herbert sailed from England to New York and joined his family in Baltimore on November 14, 1940.

Despite his early traumatic years, Herbert Friedman became a successful pharmacist and lived with his wife and sons in Norfolk, Virginia. Throughout his life, he traveled and shared his experiences with many people so that they could know the terror of living in a totalitarian state under Adolph Hitler and the Nazi party, a dictatorship that dismantled democracy, enforced a rigid cult of personality, and used terror via the Gestapo and SS (Schutzstaffel). It controlled all aspects of public and private life, pushing a racist, expansionist ideology, based on racial purity (Aryan supremacy) and anti-semitism. It led to the systematic genocide of six million Jewish people—in addition to many Roma and Sinti people, Polish and Soviet civilians, political opponents, Blacks, gays, people with disabilities, and others.

The Herbert Friedman Holocaust Materials have been digitized so that even more people can have access to his story.

Selected Letters

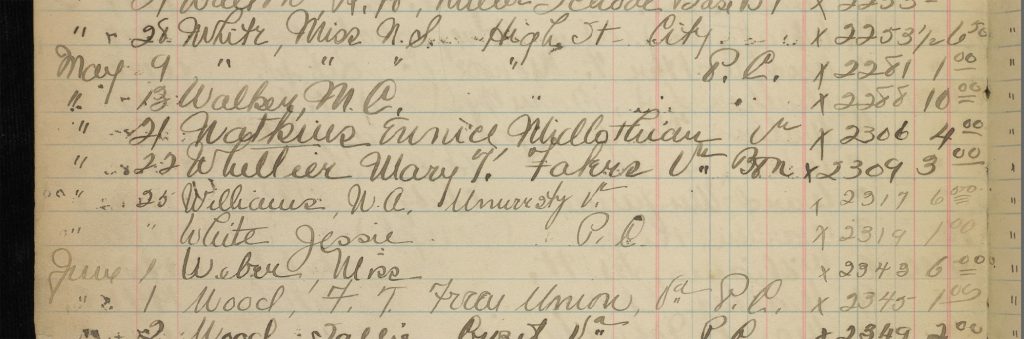

Ida Friedman letter (digitized) to her son Herbert Friedman at school in England about her efforts to get safely out of Vienna and envelope with Deutsch Reich stamp, February 22, 1939. Herbert Friedman Holocaust Materials (MSS 16906)

English translation

Dear Herbert,

I received your letter yesterday and have read it with joy. I was glad to hear how you pass the day. We thank you for your concern about us. It is for us high time to get out of this hell. Many days I am without hope. I have such longing for you and the others and start to cry when I think how dispursed we are. It is not a bad idea from you that Lilly and I should come to England. But as you say I don’t know if I could last as a domestic. I have heard that to be a maid in England is not so easy. I am unable to know what is the best advise for us to do. Vater left Dec. 18 and so far I haven’t seen a penny. For the time being Uncle Carl hasn’t sent anything and if things go on like this we’ll be in sad shape. Vater himself has nothing and he would feel ashamed to ask Uncle. So far as I see it’s going to be a long wait before I can go to America. As you write Vater and Bernhard are going to school. The Messiah is likely to come before Vater is going to be able to help us. Just imagine first they have to earn some money and only then will Uncle Carl help to bring us to America.

Now dear child be careful do not write to Uncle, Vater or Bernhard what I write to you. Vater wrote me that Uncle Carl has quite an ego, is very reach [rich] and demands respect. When you write to them you will have to consider at least times whatever you say. You must always write a thoughtful and thankful letter. G-d forbid do not ask for anything and do not complain. You wrote that Uncle Carl wrote to you to be a brave English man. You could reply that your duty is to be a good son, to help your parents have a new home and that you have great worry about your mother and sister having been left behind in such hell in the hands off such an evil. Do not write to Uncle that you are trying to get us to England as domestics. He will then think let them go to England and I won’t have to bother myself.

Now dear Herbert you ask if you should become a farmer, I would advise you to learn a good trade you could always go to farming. It would be better if you would endeavor to be with a nice family. I have heard that only after two years they will teach you a trade. I absolutely do not want you to become a tailor or shoemaker. Write how you are doing. Be brave of good behavior and diligent in learning English. Uncle Bencjan is still with us here. I suppose he waits for the glass eyed Messiah. I already wrote to Omama all about you. I enclose the picture you asked for.

This is all the news, be well and happy with heartiest regards and kisses- Mamma and Lilli, Benjan, Frau Wadichka, Wahs, Baumgarten, Schneider, Frau Krumenacher, Family Kupfer, Family Rojach and especially Fritzl and Bertie.

Post script: Dear Herbert- I am happy to hear all is well with you. You know how it is with us. I now go to Wahringer school. The Malzgasse school is shut down. I have to travel a long way to go to school. A teacher comes to the house to teach me English. Lilli

English translation

April 23, 1939

Dear Herbert:

Write to Uncle Carl and tell him that you have no peace thinking about us. That your worries will make you sick. You can’t eat or sleep thinking about us and for him to have pity to send an affidavit for us quickly. He should not take his time because each day something could happen. Beg him and write nicely. Write to him as I am telling you. From father we have not gotten anything and I don’t know when they’ll do anything and when they do it may be too late. Father is already five months in America and still has done nothing. He writes I should ask for a visa. Instead of letters I would have had our medical exam at the Consul if they had sent an affidavit. I’m sick of worrying. We hear so many things. If G’d forbid something terrible breaks out, (war) we will not live through it. I have suffered through one war already and am still sick and weak from those times. The American people don’t know what it’s like and Father thinks that they won’t do anything to women. So write to Uncle Carl and inform him that your mother suffered through one war already and then she was still young. I will not last through a second war and you write the same to Father.

This is all, stay well, your mother.

Write to me what answer you receive to your letter.

English translation

Baltimore, October 24, 1939 (Ida to Herbert)

Dear Herbert,

This is my first letter to you from Baltimore. You probably will be surprised to learn that I was even able to get out of Vienna at this time. I can’t describe to you what ordeal we underwent before departure. Once again in Vienna we suffered another repeat of Nov. 10, 1938. Some 6,000 Jews were arrested and taken to Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps. Among the unlucky to be arrested was the father of Hershel Halperin, they kept him for two weeks and then let him go. He is a very sick man. When you see Hershel tell him about his father and let him know his parents send their regards. You can tell him how lucky he is to be in England for if he had been in Vienna he would have been among those arrested. All Stateless and Polish citizens were forced out and taken away. Dear child, I can’t imagine that I succeeded in saving myself from such criminals. I was able to leave on an Italian ship and spent 10 days at sea. I was seasick the whole time and couldn’t eat anything. Vater awaited us in New York and we then spent three days with Vater’s cousins in NY Today is our first day in Baltimore and we’re staying with the Goldberg’s.

For the time being we don’t have our own place where to stay. Uncle Carl will be in Baltimore within 8 to 10 days. In the meantime I wander around and don’t miss Hitler and Wiener Schnitzel. write how you are. I think about you and am always anxious as to how you are especially since we could not write to you. I have no news from Paris. Even before we left from Vienna we were forced out of our apartment. Alex and Berti came one Sunday and just put out our bedroom furniture and we were left with no place and no money. It was lucky for us that there was an Italian ship going to America otherwise it would have been our demise. Vater sent us two ship tickets which cost $400.00. In Vienna the ship agency would not accept German Marks. As soon as I got the ship tickets I left everything behind and just ran. You cannot imagine what life is like now in Vienna for Jews. There is much hunger for Jewish people, for 4 weeks we lived on bread and tea. The Gestapo confiscated all assets from the Kultusgemeinde. Since the Kutusgemeinde has no money and one can be sent in from abroad and all borders are closed it is impossible to leave. Tell all the people in England to take an interest on the unfortunate persecuted Jews in Austria

This is all the news, stay health. The next time I”ll write more. Many regards and kisses from your Mama.

Dear Herbert, Now I am in America and I can write you that I am sorry because I have left Hitler alone. I fear he won’t last since I left him behind. The poor Hitler I feel sorry for him. (This is said as a joke.) Now to substance, I had a good journey. I liked Genoa in Italy and the Italian people. I did not get seasick on the ship but Mama was very sick. The captain of ship and waiter spoke with me in English and I understood very well. They were very friendly. I like New York but it can’t be compared to Vienna. I like Baltimore with single homes much more. Because I don’t know what else to write I shut the letter with many regards and kisses from your sister. Lilli Many regards and Kisses from Vater.

English translation

Baltimore, November 22, 1939

Dear Herbert,

We received your dear letter and were glad to hear from you. Now we are able to write all about us. However, not in English, you have slightly overestimated our acquaintance with English. We are responding in German lest you forget it. Now, I’ll tell you everything from the beginning.

As you may know, we were supposed to leave Austria via a German shipt the “Bremen” sailing from Cherbourg, France to the US. With the outbreak of war all sailing of passenger ships were canceled. We had lost all hope of ever leaving the prison we felt to be in. We indeed had nothing to eat and generally what little seemed available went to Aryans. If this wasn’t enough for us we also forced from our apartment. We had no news from anyone and in a desperate situation. Then, with G’ds help we learned that Dutch and Italian ships still sailed. However, a fortune in money was required to book a fare. In addition there was a new requirement that all payments had to be in US dollars. Payment in German marks was not accepted. Dutch and Italian shiplines were able to sail because their country was neutral. How could Jews in the German Reich have US dollars? Nobody had it. We sent a cable to Vater asking to get us two tickets for an Italian ship. Cable messages sent back and forth and three long weeks passed before with luck we received the tickets. Now the circumstance was that many people had visas and some had ship tickets yet were unable to leave because the ships were fully booked for months in advance. We had lost all hope when the Germans passed a new Law that all persons who wanted to ravel out of Germany had to have also an exit visa and that was only available to German citizens. Stateless and Polish Jews were not allowed to leave this was followed by another terrible act in that non-citizen men were then arrested and taken to Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps, no longer to return. Thereby, many people who had ship tickets were unable to leave and ship space was again available. We left at once, within four days of our booking. We took a train for Genoa, Italy. Surely, you know that Uncle Bencjan had gone to Italy before us. In the beginning he stayed in Milan and he was being helped by the Jewish Relief Committee but it was shut down and he was left with nothing. When walking out from the Committee building he was taken into custody by the Italian police. Since he had no proof of any source of income he was ordered out of Italy. He was on his way back to Vienna when reconsidered and decided to to go to Genoa which is another city in Italy. By coincidence our ship left from Genoa and thus we were able to spend two days together. He met us at the train station and he looked in a terrible state. He had no money. there is no relief help, each night he sleeps somewhere else. We thought we could give him the 8 dollars we had with us but couldn’t give him much since we had to pay for 2 nights stay and to eat. You can imagine the sadness and how he cried as we embarked our ship. He has nothing to wear. He had sent all things to Paris thinking of crossing the border into France and now he has nothing. We brought him a few things, but I tell you he is in terrible shape. His only hope is for us to get him an affidavit.

Now as to our ship, the first 3 days of sailing were very nice. We did not even feel we were on an ocean. On the 4th day the problems began. We were on route to Algiers in French Africa when the ship was ordered to halt by a French warship. After a long back and forth discussion and just as we thought they would let us go, the French in contact with the British issued an order that all men with German passports and between the ages of 18 to 50 would be removed for internment in Algiers. You can well imagine the upset and crying that went on among their families. If Vater had been with us then he too would now be interned in French Africa. The following day the sea became very rough and many people became very seasick and stayed in bed. Just a few it seemed were alright. Mama could not eat anything. vomited the whole time and stayed in bed. I however felt fine and enjoyed the ship the rougher the ocean got to be. I organized my time and always found something to do. If I stopped by to see Mama she told me to leave the cabin lest I too get sick. I went to explore the 1st and 2nd class of ship and went to the cinema. Though, I don’t understand Italian I could understand those in English a little bit. When I really had nothing to do, I conversed with the Captain, waiters and sailors and understood them very well since I had studied English for six months. It took 10 days for the ship to arrive in NY. Vater, an Aunt and cousin from Vater’s side of relatives met us. We stayed in NY for 3 days. Mama was weak and this allowed her to rest before proceeding to Baltimore. We arrived here at night with no place of our own to stay. Vater and Mama stayed in a room and I went to stay with a family who were friends of Vater. The next day we were invited to dinner at cousin Goldbergs and I have stayed with till now. While in NY we called Uncle Muszkat and he told us he would shortly see us in Baltimore. So far 4 weeks have passed and we haven’t seen him. The 600.00 $ we had have been spent. The ship tickets cost 400.00$ the rest was for Bernhard at 10.00$ per week, a dentist and cables. In short the $600.00 is gone.

The relatives don’t want to do anything for us. I have no good wishes for Uncle Yitzchak and wife. In particular his wife who was against helping our family to come her. Not even once has he come to see us and has no interest in us. Whenever we need help he stands to the side. As it is. G’d has punished him for his wife’s bad behavior as his wife needs to be hospitalized. On our own we found a place to stay and now have 2 rooms and a kitchen for $ 23.00/month which includes heat and light. Not a cent has been contributed by our relatives. We have a place where to stay but no furniture. Every little item we gave away in Vienna we now have to buy anew. Vater hasn’t had much work but now it is a little better. Bernhard works but so far hasn’t given us anything. He lives by himself and pays for his own upkeep. He is going to live with us and hope that he will contribute in paying the rent.

We received a letter from Uncle Carl and he wrote that he won’t come this month but the next. He also tells us to go to Uncle Yitzchak and ask to give us $50.00 which he will refund and that Yitzchak should on his own add something as well as cousin Goldberg. to enable us to buy some furniture. Yitzchak old us to ask Uncle Carl to send us a check, he is not giving us anything. He is a bad person. Mama sent a letter to Uncle Carl who is now in New York.

As for me, as yet I’m not going to school because of where I live. I’m staying with cousins Goldberg and twice a week go to English clas. I would like to write more but my hand is beginning to hurt. I’m amazed to see I’ve written 8 pages. I conclude this letter with many regards and kisses from Vater, Mama and Bernhard. I have a picture of you of where you went with a family for tea and am not satisfied as to how you look. You should eat more and not worry so much. A wait a long letter from you. Your loving sister.

English translation

Baltimore, October 8, 1940

Dear Herbert,

You cannot imagine the joy we felt upon receiving your last letter. For almost four weeks we had not heard from you. You had promised us to write every week and you have not kept your promise. We know that all is going on in London and the tragic sinking by the Nazis of a ship with 83 children aboard. We cried day and night. When I think that you too will go by ship my heart beats with freight [fright]. When you sail do not sleep at night for the first few days and always wear your life preserver belt.

We wish for the moment of your arrival in New York. Take good care of all your things as I know you are very forgetful. From whom did you get the $10.00 for the Visa? Your ship’s ticket of $137.00 was paid by the person who sponsored the affidavit and was sent to the American Consul. Don’t forget to bring with you a small gift for Mrs. Strauss of the Hias Committee. She did a lot for you. Also, bring something for the man who gave the affidavit, something like a lighter for cigarettes. If you don’t have the money then borough a few dollars and I will reimburse with great appreciation. Do not bring me any stockings. You don’t know what kind I could use because I have small feet. Do not forget your ring and watch. Many people already await your coming with great impatience. When you arrive in New York a member of the Committee will meet you and if they inquire if you have any money, say no and they’ll give you the busfare to Baltimore. Perhaps we’ll be at the port when your ship docks.

This is all the news. We are in good health. We hope you have received all the letters we mailed to you. We greet and kiss you and eagerly await the moment of your arrival.

Your parents

Interesting quotes and information from letters in the archive:

Ida wrote to Herbert, “You know dear child, how we are now all dispersed in a different land. Therefore, you must try to bring the family together again. You know very well that I am helpless about our situation.” (December 21, 1938)

Ida wrote to Herbert that children were required to change their names to Jewish first names. She and Lilli were called Sarah. Her brother, Benjcan was called Israel. Ida advised Herbert that he was too young to go to Palestine. “You must be 15 or 16 years old or be part of Zionist organizations to go to Palestine.” (December 26, 1938)

Ida wrote to Herbert that it was better for him to be in England, “Be thankful to be free of the murderer’s hands. I am desperate and still in this hell of life. Don’t be homesick; you have no home. Try to live with a family in England and learn a trade.” (December 30, 1938)

Ida wrote to Herbert, “I wanted to send 10 Reichsmark to Grandfather in Poland but this is not allowed. It is against the law to send any money out of the country.” (January 3, 1939)

Ida mentioned a newspaper article about a new Nazi requirement. “We have to turn in all jewelry. I don’t know what to do with my pearls, Lilli’s watch and other things. Now they are taking away whatever we have.” Ida also wrote that she was waiting for an affidavit from the American Embassy. Herbert wanted her to come to England. She was conflicted about it. “In Vienna it costs 52 Reich Marks for 2 visas. In England it is 20 US dollars. Where am I going to get that money. Who would give it to me? Now I don’t know what I should do. If I could be sure we could leave in a short time we would stay here… but I fear it may be a long time before we can leave.” (March 7, 1939)

Bernhard Friedman wrote to his brother Herbert, “The newspapers here are full of news about Hitler and what he is doing in Germany. Last Sunday 70,000 people demonstrated against Hitler. They demolished the German Consulate and German businesses, in short, it was a riot and took place in New York.” (March 27, 1939)

David Friedman wrote to his son, Herbert that he was trying to get an affidavit from Uncle Carl Muskavit so Ida could come to the United States. “It is very nice that you are trying to help Mama through your Refugee Committee. However I want her soon to come to America rather than England. I am doing everything I can for Mama.” (March 27, 1939)

Bernhard Friedman wrote to Herbert, “It is bitter that Mama has been thrown out of her home. I believe Vater cannot get a weekly income statement because his job is not permanent. You must understand we can only do so much.” (April 7, 1939)

Ida wrote to Herbert about her concern for her Omama (mother) and her brother Bencjan. “Omama has not written for a long time. Her permit to stay in Paris expired on May 10th. I don’t know what will happen next. Later Herbert added notes to the letters explaining that Omama (Golda Muzskotlblit) died in Paris shortly after her arrest and Bencjan hid in Italy where he was arrested and deported to Austria. He escaped to France and was arrested again. He died at the concentration camp, Auschwitz. (May 28, 1939)

Ida wrote to Herbert “The newspapers announced yesterday that Jewish people who became Austrian citizens within the past eighteen years will be stripped of their citizenship.” (July 17, 1939) She also wrote, “I read in the papers today that entry into the United States will be closing for five years.” “Write to Vater and ask him what he has done.” “Everyone is leaving and I am still here. Only for me is such a sad fate.” (July 18, 1939)

In a letter to Herbert, from his cousin Marthe Rozencwadj, she referred to French film star Francoise Rosay, who was awarded the French Legion of Honour for her radio broadcasts against Nazi Germany. Marthe quoted Rosay as saying on Radio Algiers, “I wish that for all times (forever) the regimes of dictatorships such as Hitler’s be abolished; That the whole world touch hands; we are all human beings; we all have a home, children, a family.” (October 5, 1939)

Ida wrote to Herbert, “Once again in Vienna we suffered through another repeat of November 10, 1938. Some 6000 Jews were arrested and taken to Dachau and Buechenwald concentration camps. (October 24, 1939)

At the height of her despair, Ida received good news: “Now dear child I can report with great joy that I received notification to come to the America Consulate…for our physical exam.” (July 26, 1939) On October 24, 1939 she was able to write Herbert, “Dear child, I can’t imagine that I succeeded in saving myself from such criminals. I was able to leave on an Italian ship R.M.S. Samaria and spent 10 days at sea.”

For more information about Herbert Friedman:

Rasmussen, Frederick N. “Herbert Friedman, who escaped the Holocaust and later became a successful pharmacist, dies.” Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, IN), October 10, 2020.