This is the second in a series of four blog posts, spotlighting the mini-exhibitions of fall semester 2014 students from USEM 1570: Researching History. The following is the abridged version of the students’ final projects, featured at their outreach program, Tales from Under Grounds II.

***

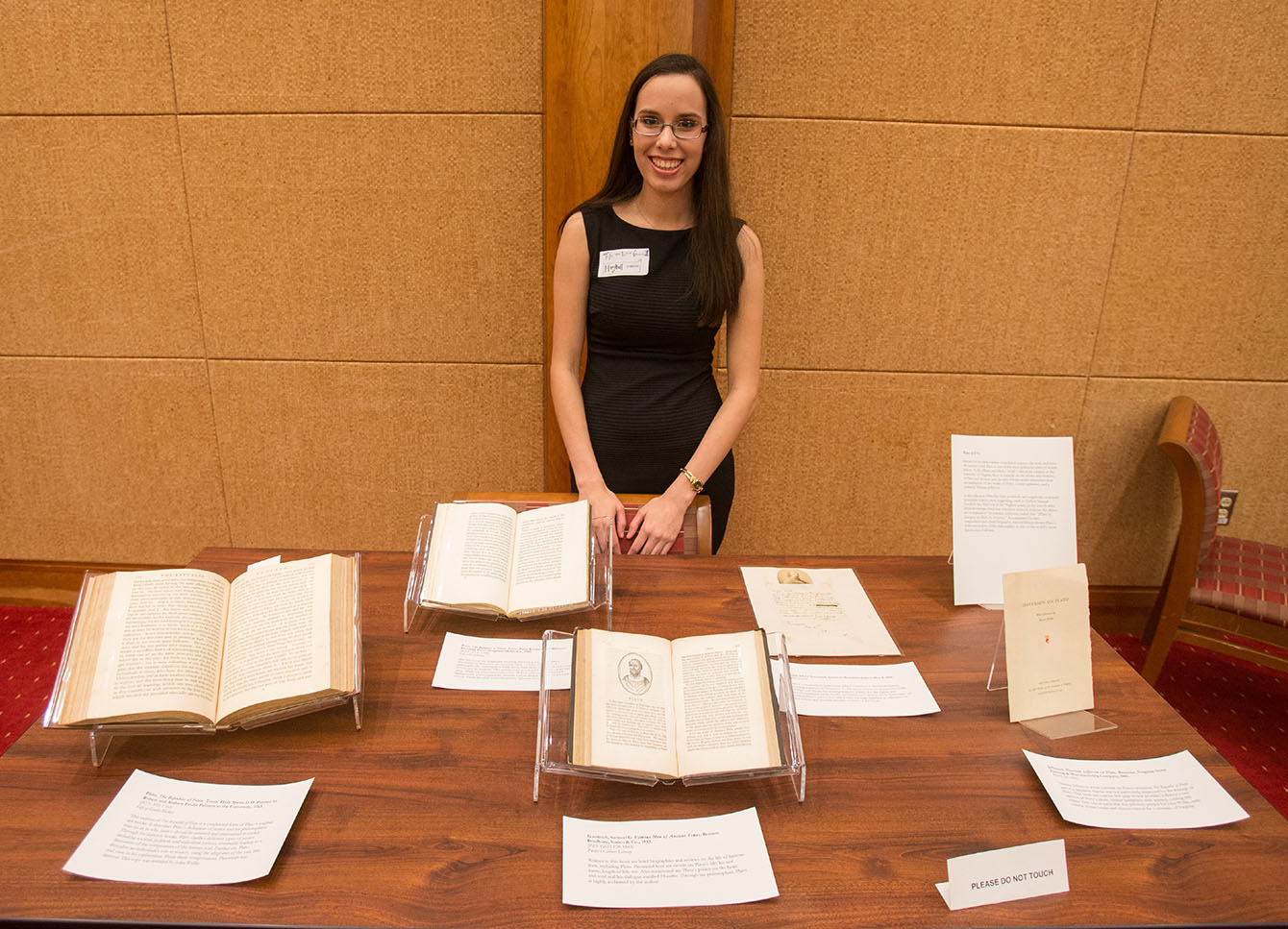

Regina Chung, First-Year Student

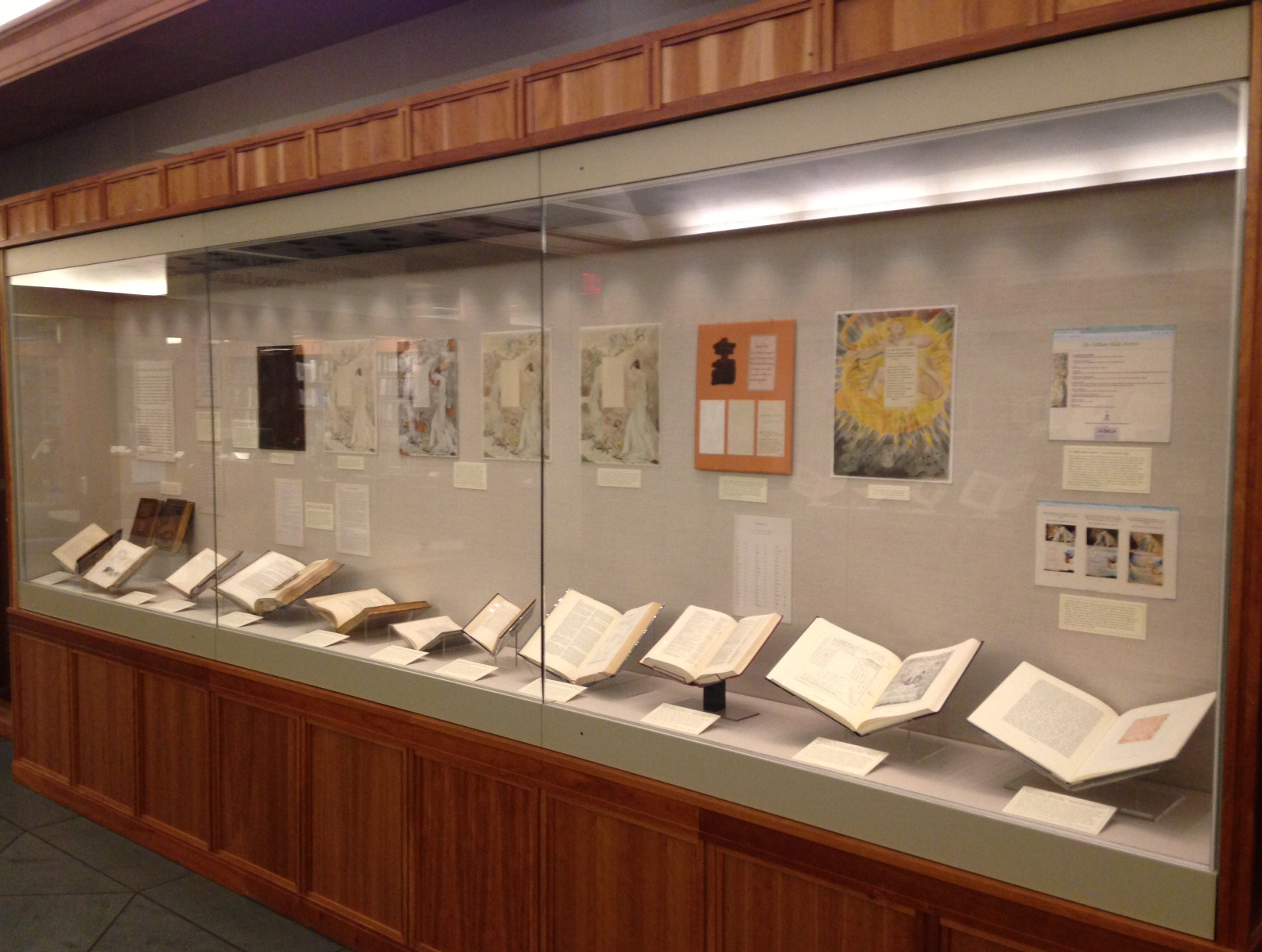

Monticello Music

Thomas Jefferson declared that music “is the favorite passion of my soul, and fortune has cast my lot in a country where it is in a state of deplorable barbarism.” Jefferson practiced the violin three hours a day and would later share his love for music with his wife, Martha, and then his daughters. He would not only spread this passion among his family, but also as a political tool that would lead to wide popularity with his lively campaign songs.

Using scrapbooks, notebooks, music programs, political campaign songs, and newsclippings, this exhibition displays the passion Jefferson held for music in his personal and work life.

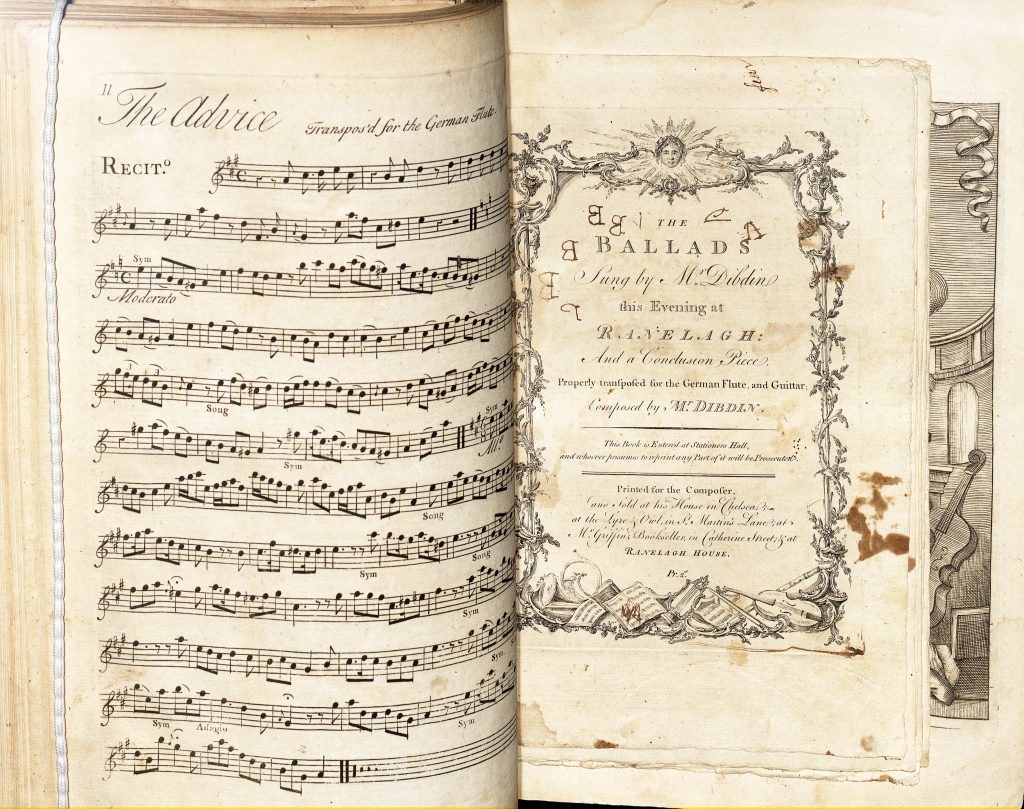

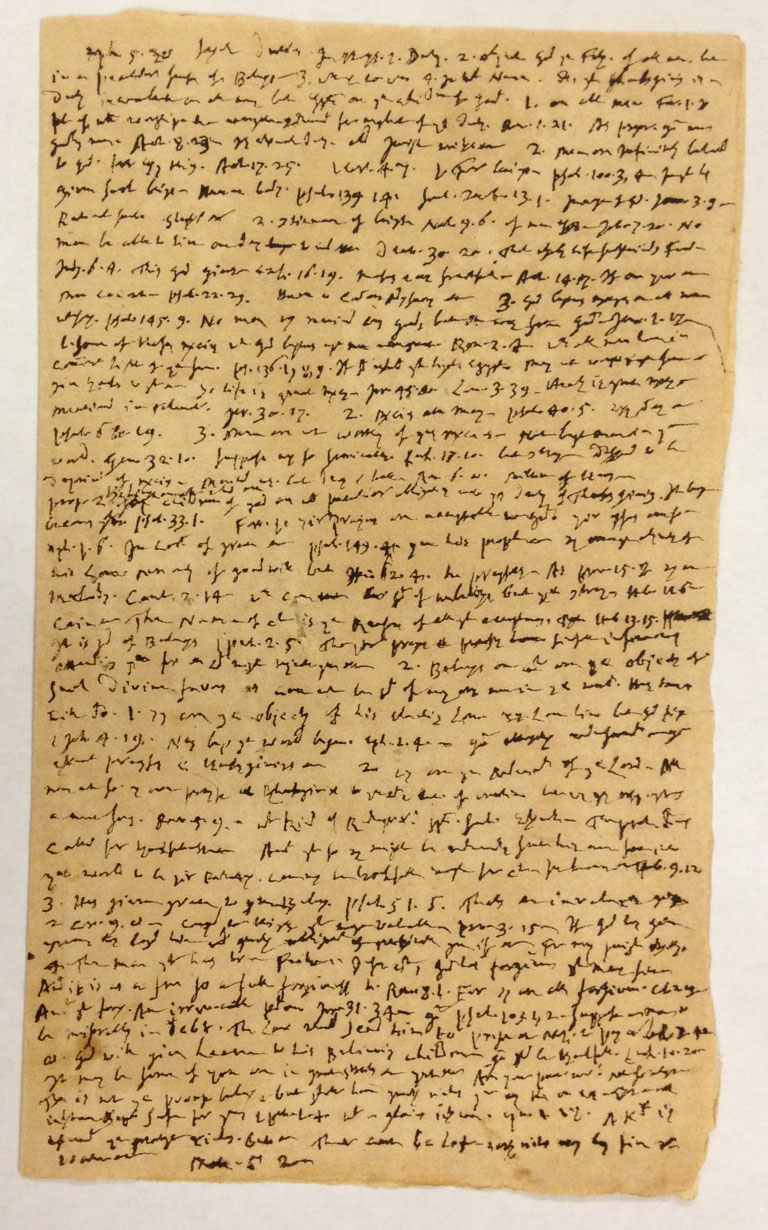

Thomas Jefferson’s Scrapbook of Sheet Music. This scrapbook of 18th century songs, ballads, and cantatas were collected by Thomas Jefferson and his family. There are 95 titles in this volume from Jefferson’s distinct music collection. (A 1723-90 .J4 no. 1. Tracy W. McGregor Library of American History)

Newsclipping of a letter written by Thomas Jefferson to his daughter Martha “Patsy” Jefferson, n.d. After Jefferson’s wife’s death, he strongly enforced music upon his eldest daughter, Martha (“Patsy”). In this reprinted letter, he encourages her to continue to learn new music. (MSS 6696. Thomas Jefferson Foundation)

***

Lily Davis

Nathaniel Hawthorne

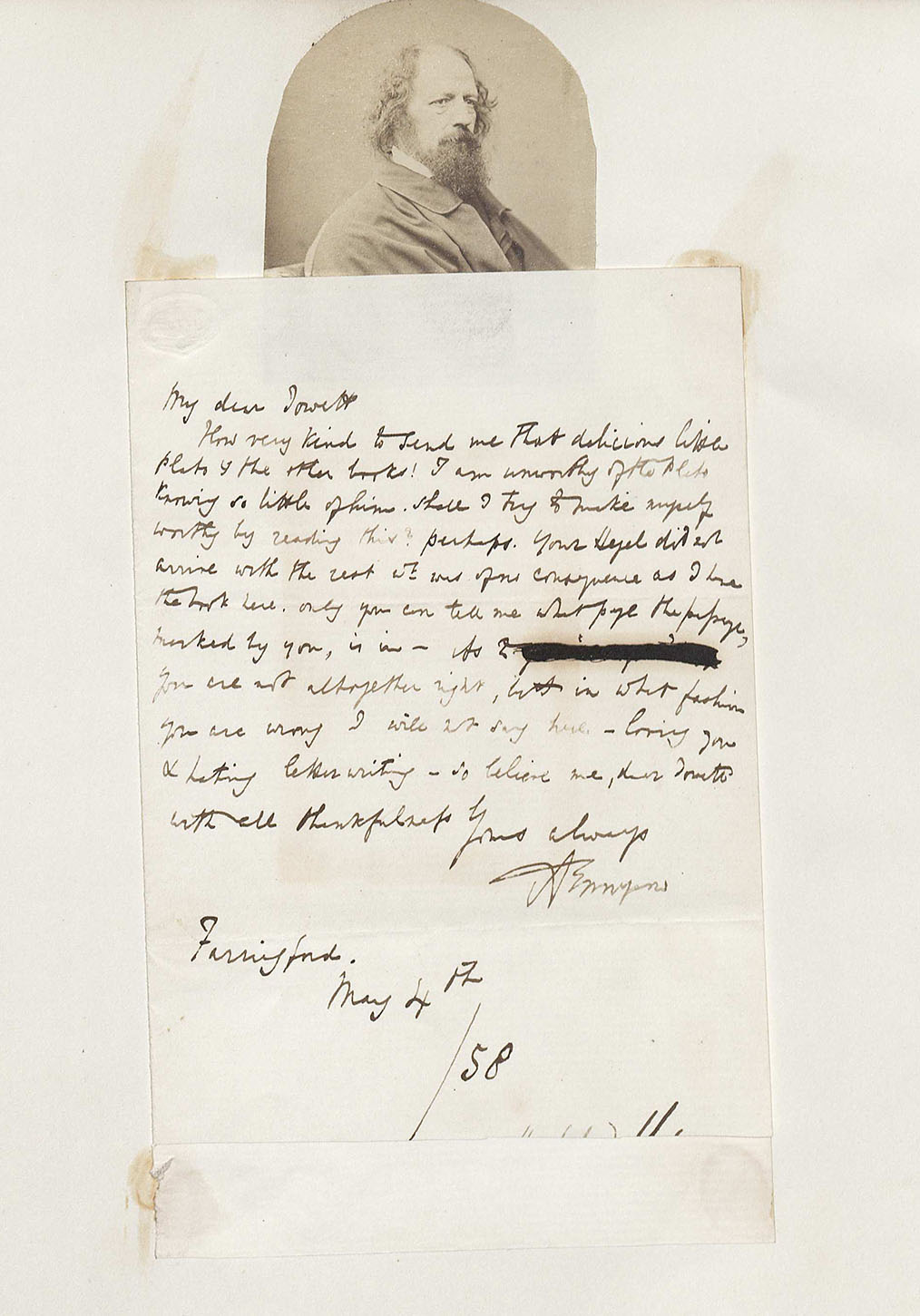

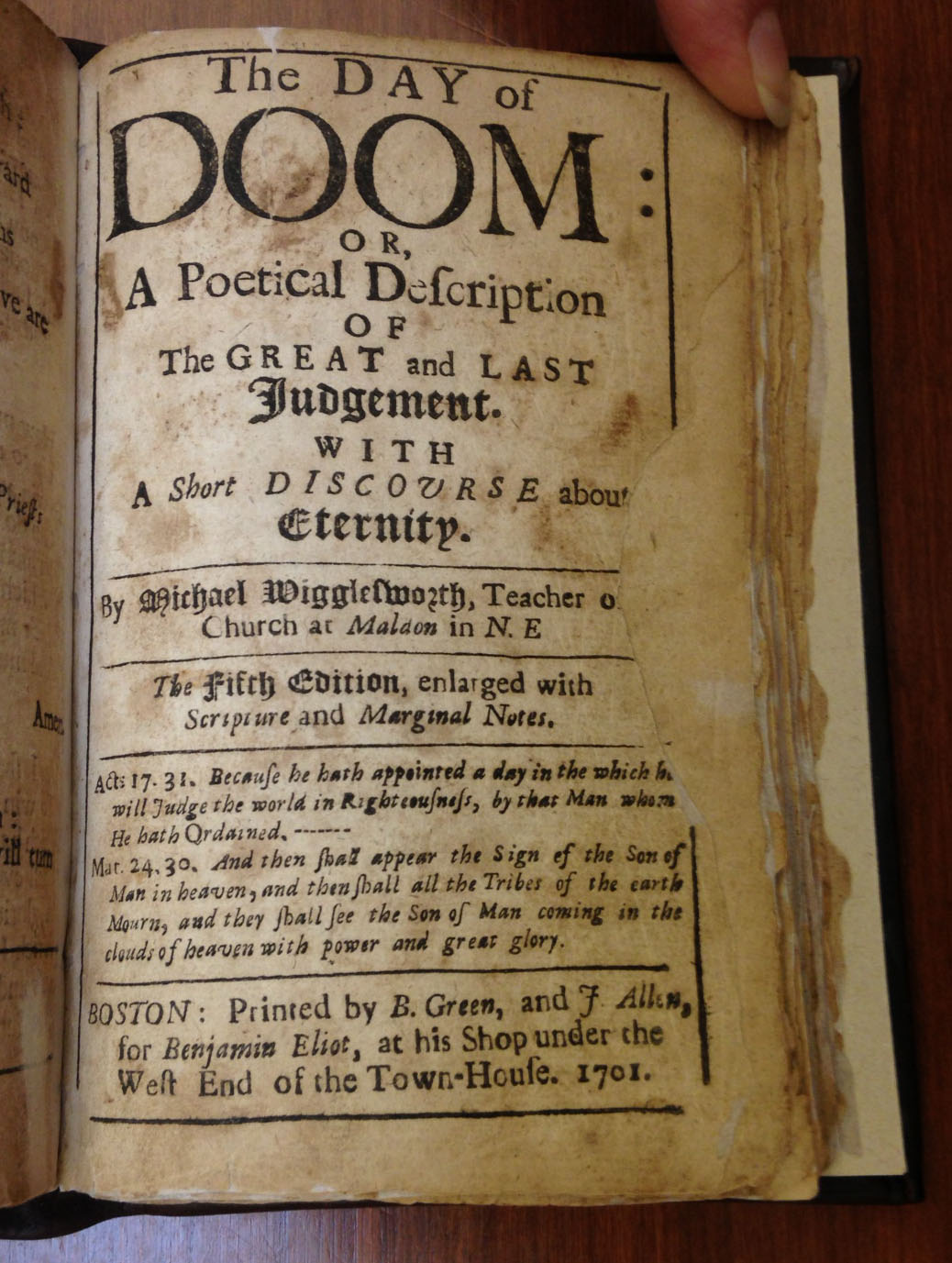

Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864) was a 19th-century American author. He is known as a “romancer,” examining the inner nature of man, and as a “realist,” using literature to articulate the flaws in American society. Many of his stories have a common theme of probing human nature and criticizing culture. In his books, he examines and scrutinizes Puritan society, which points back to his long line of Puritan ancestors.

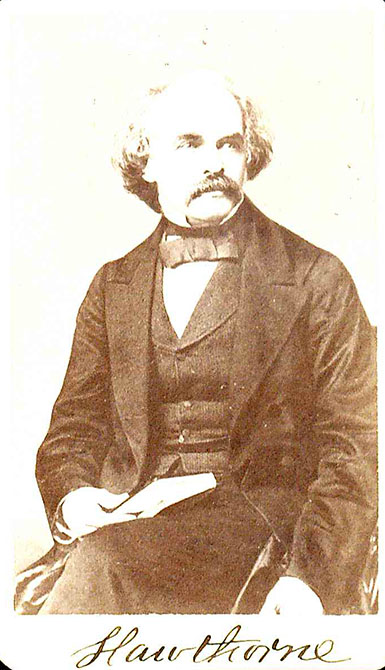

The photograph of Hawthorne with his signature across the bottom was taken around the time he wrote The Scarlet Letter and The House of Seven Gables, pieces of literature that are still read and loved today. The Scarlet Letter, probably Hawthorne’s most well-known book, provides insight to his Puritan background. The House of Seven Gables was published shortly after The Scarlet Letter and is also set in 19th century New England. Centuries later, Hawthorne is still considered a great American author.

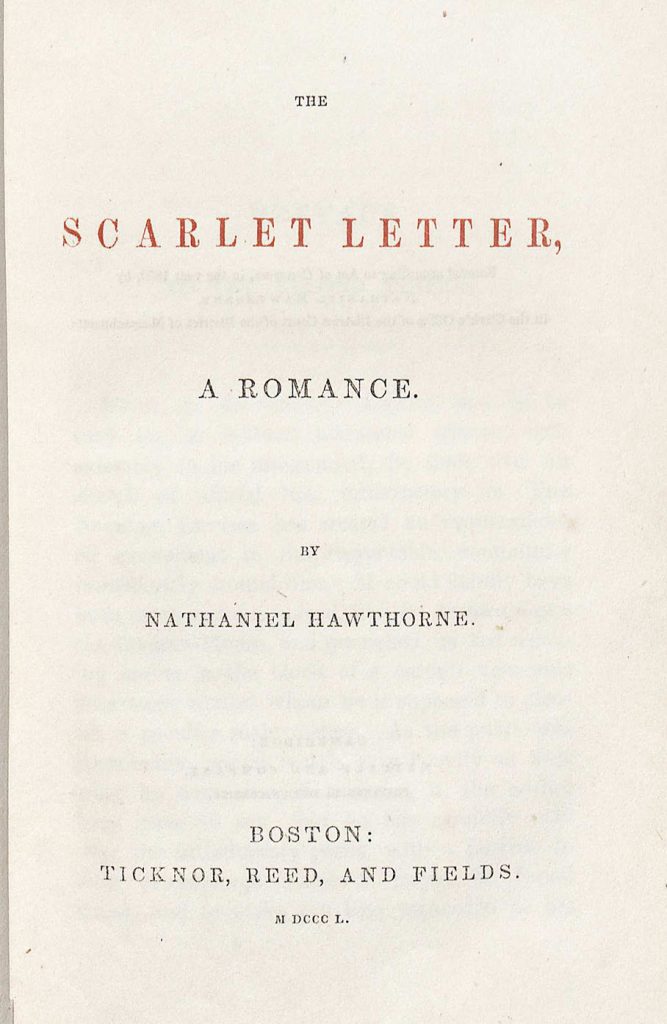

Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The Scarlet Letter. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1850. The Scarlet Letter, published in 1850, tells the story of Hester Prynne and her illegitimate child Pearl in Puritan society. This novel was inspired by Hawthorne’s strict Puritan background. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s great grandfather, John Hathorne (1641-1717), lived in Salem, Massachusetts and was a prominent judge in the Salem witch trials. Nathaniel Hawthorne eventually added the “w” in his true family name of “Hathorne” (changing it to “Hawthorne”) to distinguish himself from his ancestors. In reading the Scarlet Letter, it is obvious that his writing points to his background.(A 1850 H39 S3. Tracy W. McGregor Library of American History)

Signed Carte de Visite of Nathaniel Hawthorne, ca. 1850s. (MSS 6249. Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature)

***

Mary Elder, First-Year Student

Games of American Children in the Victorian Era

The Victorian Era is viewed as a time of rapid development and change, and it is easy to overlook the role of children in this era. Many of people’s ideas come from films such as A Christmas Carol, and characters such as the grandmother of American Girl’s Samantha, but much can be learned by looking at the toys and games that children enjoyed during this time.

Games and stories can often reveal the values of the time they were played, and Victorian Era games frequently had educational value, or intended to teach moral lessons. Other times, they were simply to keep children occupied quietly. Outdoor and recreational activities were also encouraged to allow children to run and play, but were sometimes limited to boys as many still held the belief that girls should be quiet and dainty.

These games can tell a story as they give us a glimpse into the lives of the younger generation in the late 19th-century. Many of the games and concepts might be familiar to people today and can show the continuity in children’s attitudes toward fun and perpetuity of childhood pleasures.

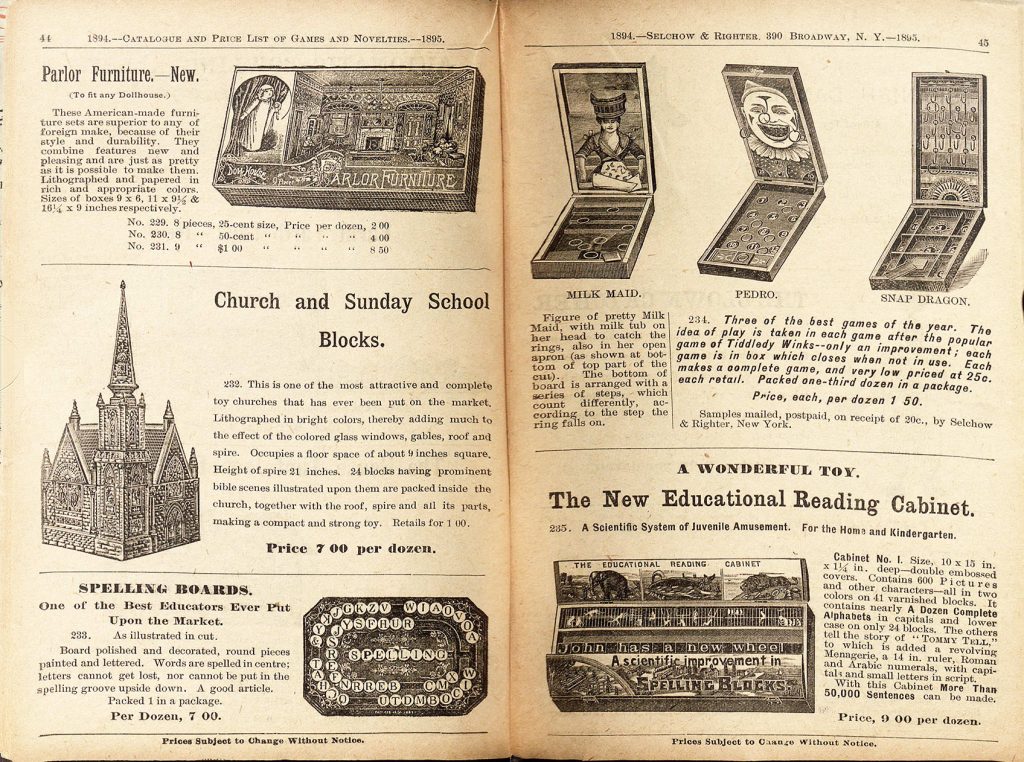

Selchow & Righter, New York, Manufacturers and Wholesale Dealers in Games and Toys, 1894-1895. This trade catalog for toys and games provides images, cost, and descriptions of the games. Frequently sold by dozens, costs vary greatly, but many are in the $7-$10 range. Many items, such as the church and blocks, have religious associations, while others, such as the Spelling Boards and reading cabinet, are educational. Many items, such as a ring toss, dolls, toy pianos, and air rifles, would be familiar to children today. (TS199 .A5 T62 no.16. Albert H. Small American Trade Catalogs Collection)

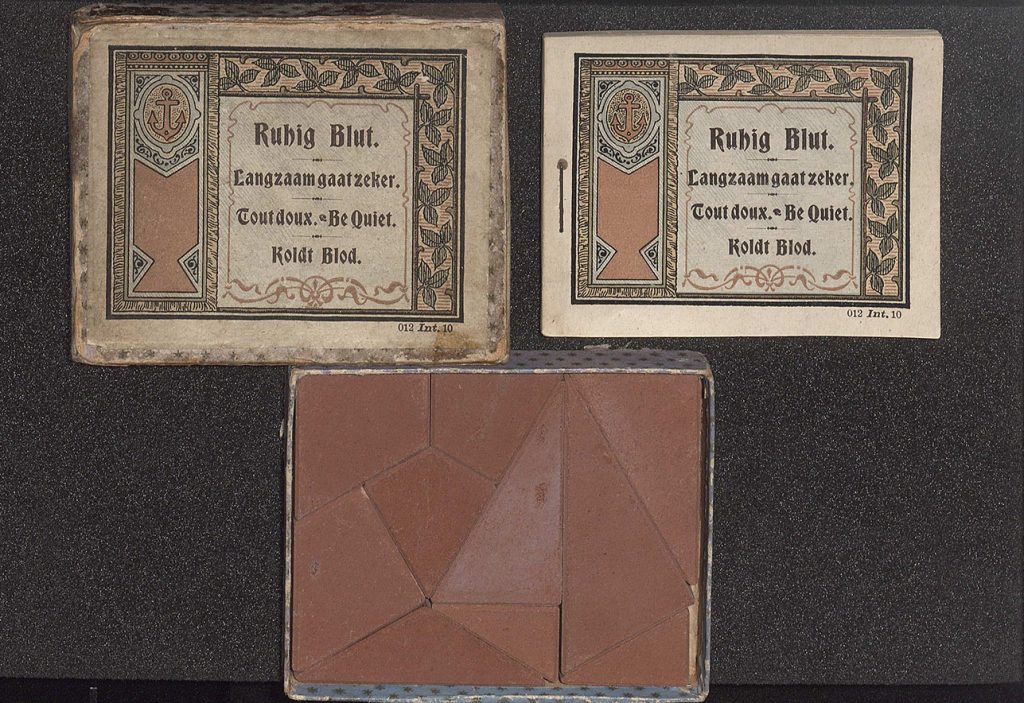

Ruhig Blut. New York: Dr. Richter’s Publishing House, 1899. This puzzle, whose name in English is “Be Quiet,” has instructions in German, English, and several other language. It resembles what is now known by many as a Tangram, and the small shaped masonry pieces could be combined in a variety of ways to create pictures. (Lindemann 05868. The McGehee Miniature Book Collection)

***

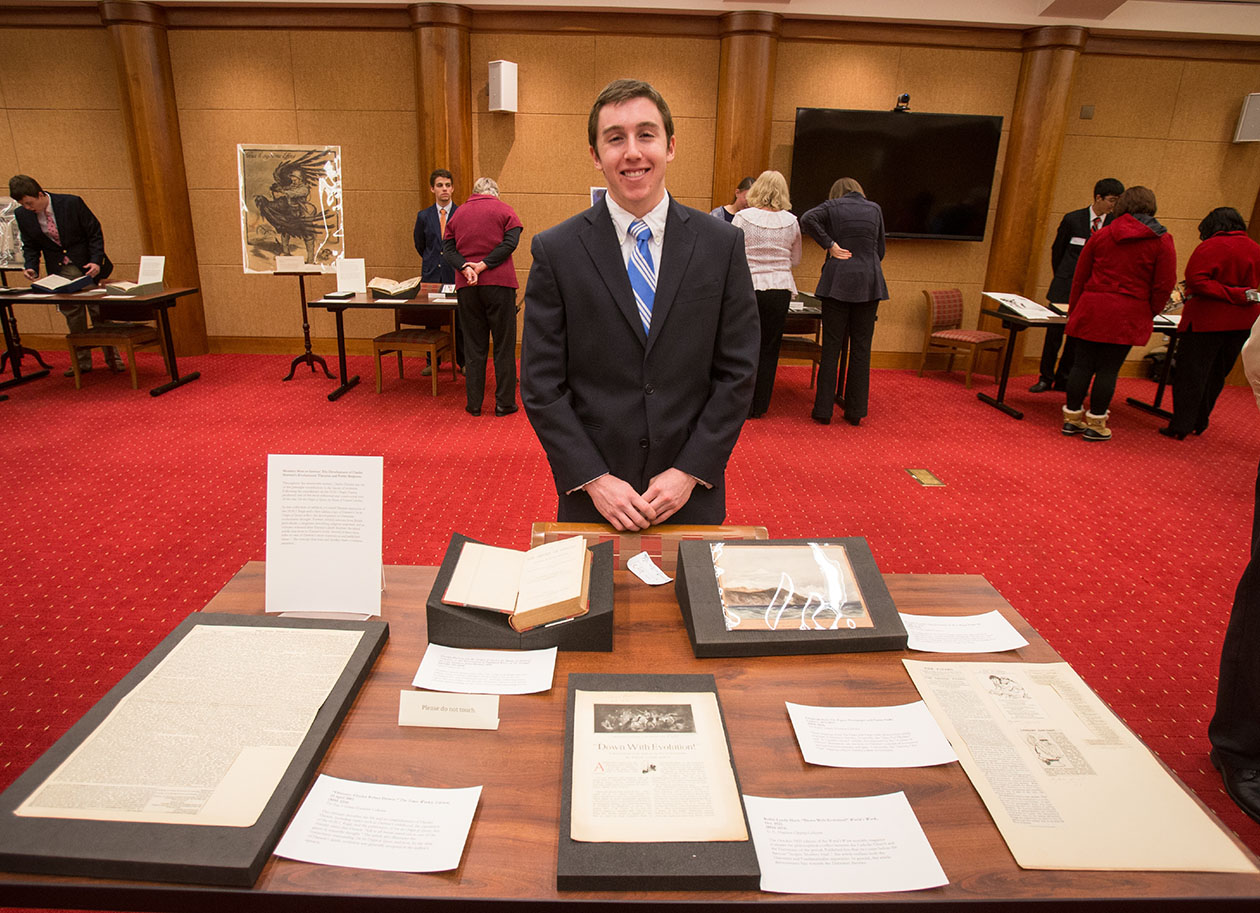

Grace Kim, First-Year Student

Grace Kim talks to Rare Book Cataloger Gayle Cooper about her exhibition, November 18, 2014. (Photograph by Sanjay Suchak)

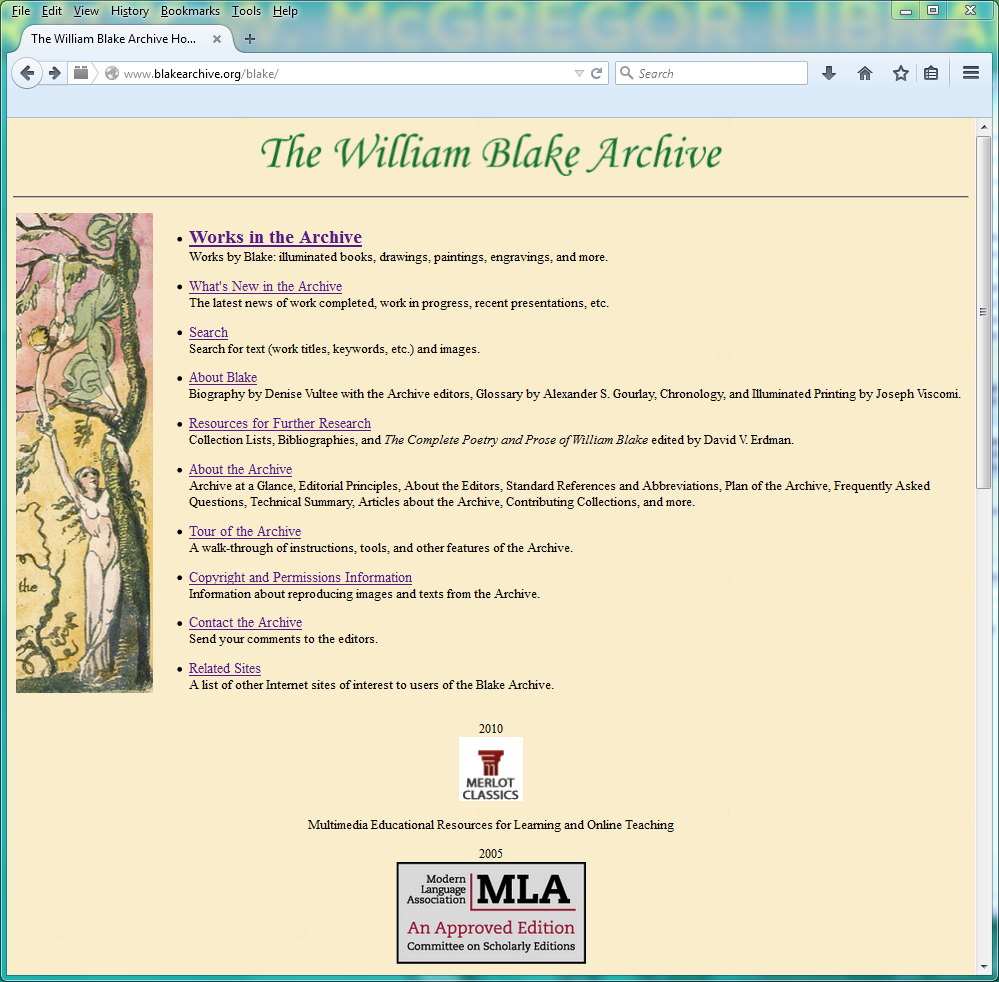

John Tenniel: An Illustrator with a Punch

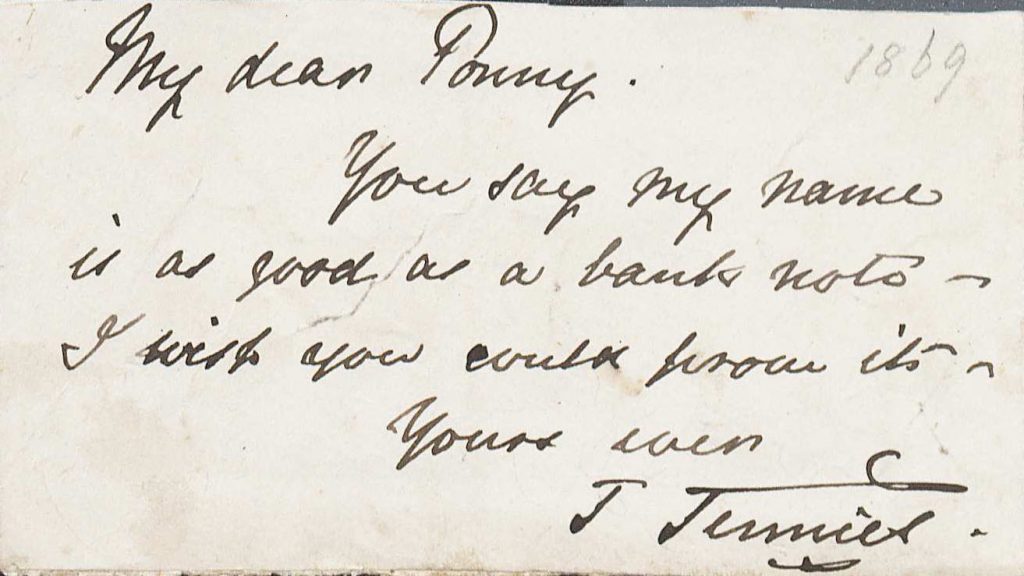

Originally, John Tenniel was a classic artist who created oil paintings for the Royal Academy. Dissatisfied, he left to join the illustration world. In 1850, he found a position at the British political magazine Punch, where he would work for fifty years. Citizens soon recognized his drawings, and his work at the magazine would soon allow for other illustrating opportunities. He drew for Thomas Moore’s oriental romance novel, Lalla Rookh, which was considered to contain his best illustrations. He was also the illustrator for The Arabian Nights edition, created by the engravers the Dalziel brothers. Tenniel would constantly go to the Dalziel brothers for the engraving of his drawings.

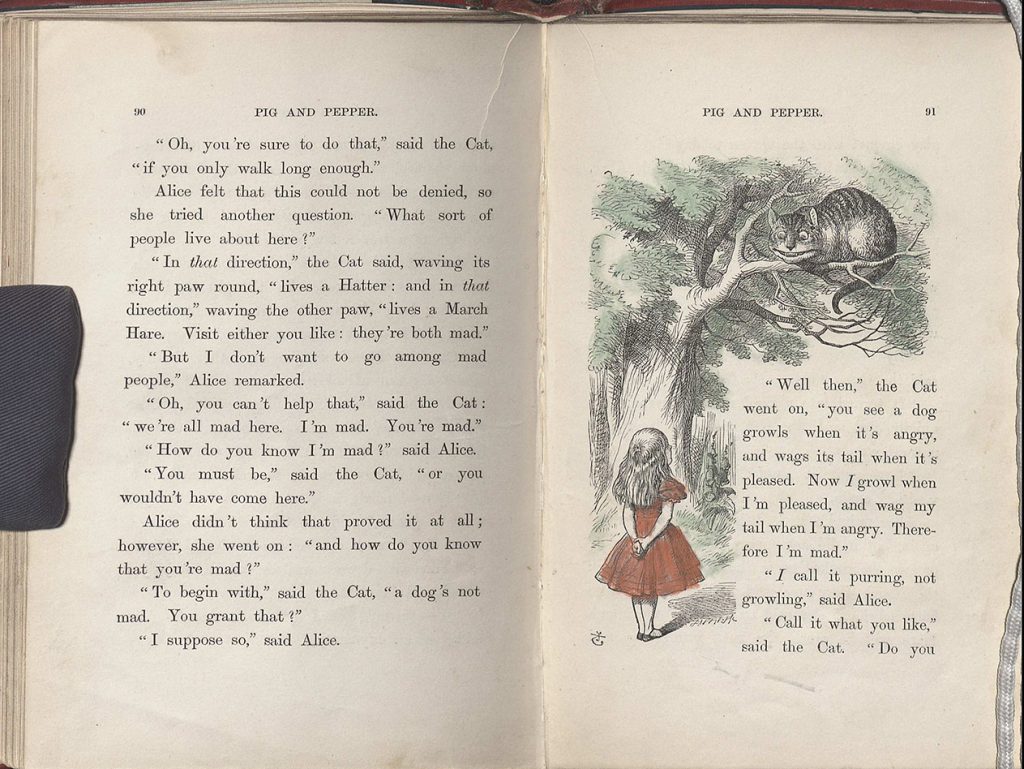

Tenniel preferred not to use real life models to help him form his illustrations. Instead, he claimed that he could draw anything through the use of memory. This may have helped him when he worked with Lewis Carroll, otherwise known as Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, to create Alice’s fantastical world.

In 1893, John Tenniel became knighted for his work in political cartoons and illustrations. After he retired from Punch about a decade later, he would not take on any other projects.

Lewis Carroll. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Illus. by John Tenniel. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1866. Most well known for his work with Lewis Carroll, Tenniel includes forty-two of his illustrations in this first American edition. Originally, Carroll wanted to draw the illustrations himself; however, a friend, Thomas Combe, suggested a professional illustrator instead. Lewis Carroll wanted no one other than John Tenniel. His work at Punch led the surreal author to become a big fan. In this particular book, the color marking comes from the original owner, Alice Huff Johnston. (PR4611 .A7 1866. Gift of Clement Dixon Johnston)

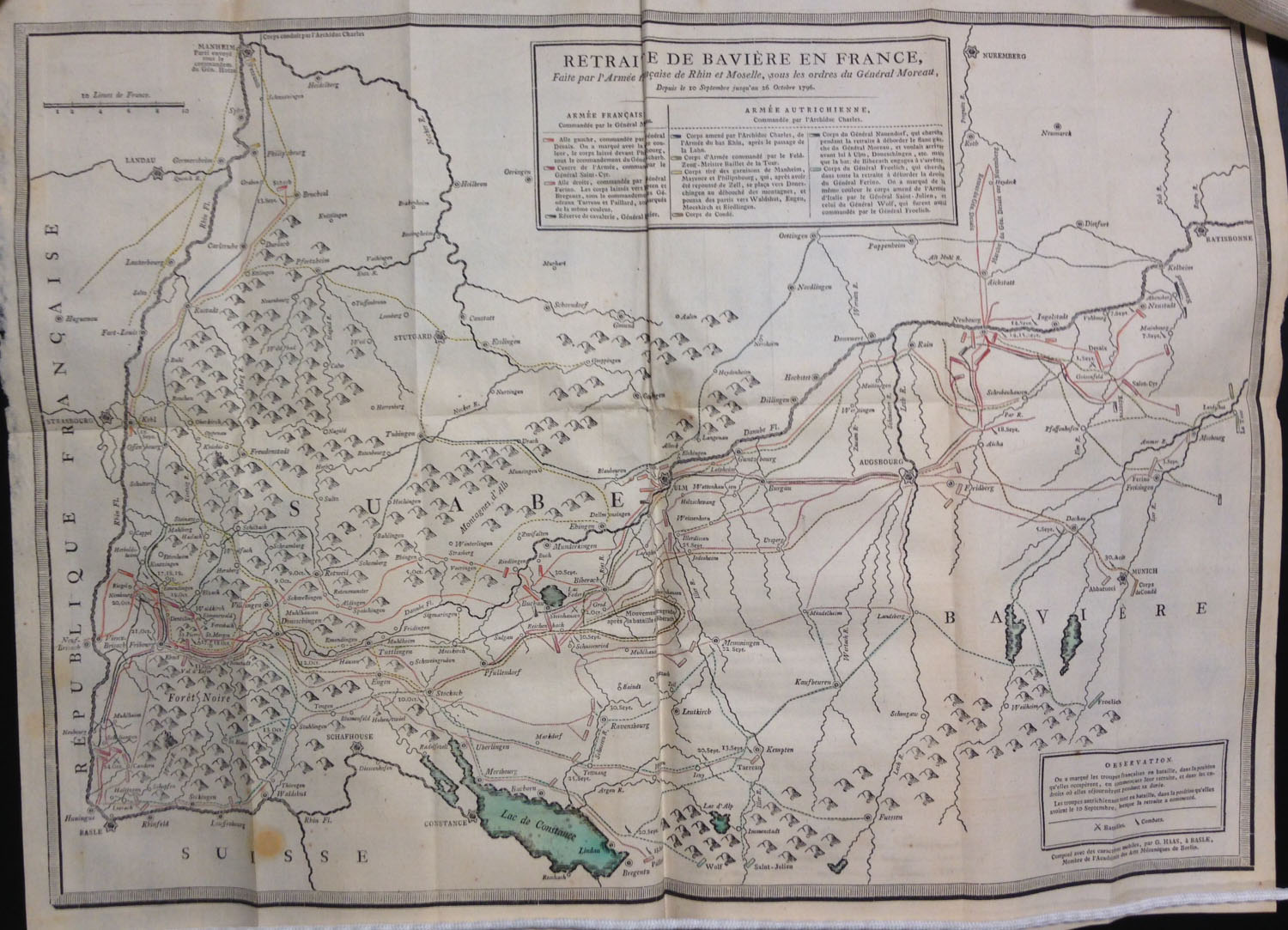

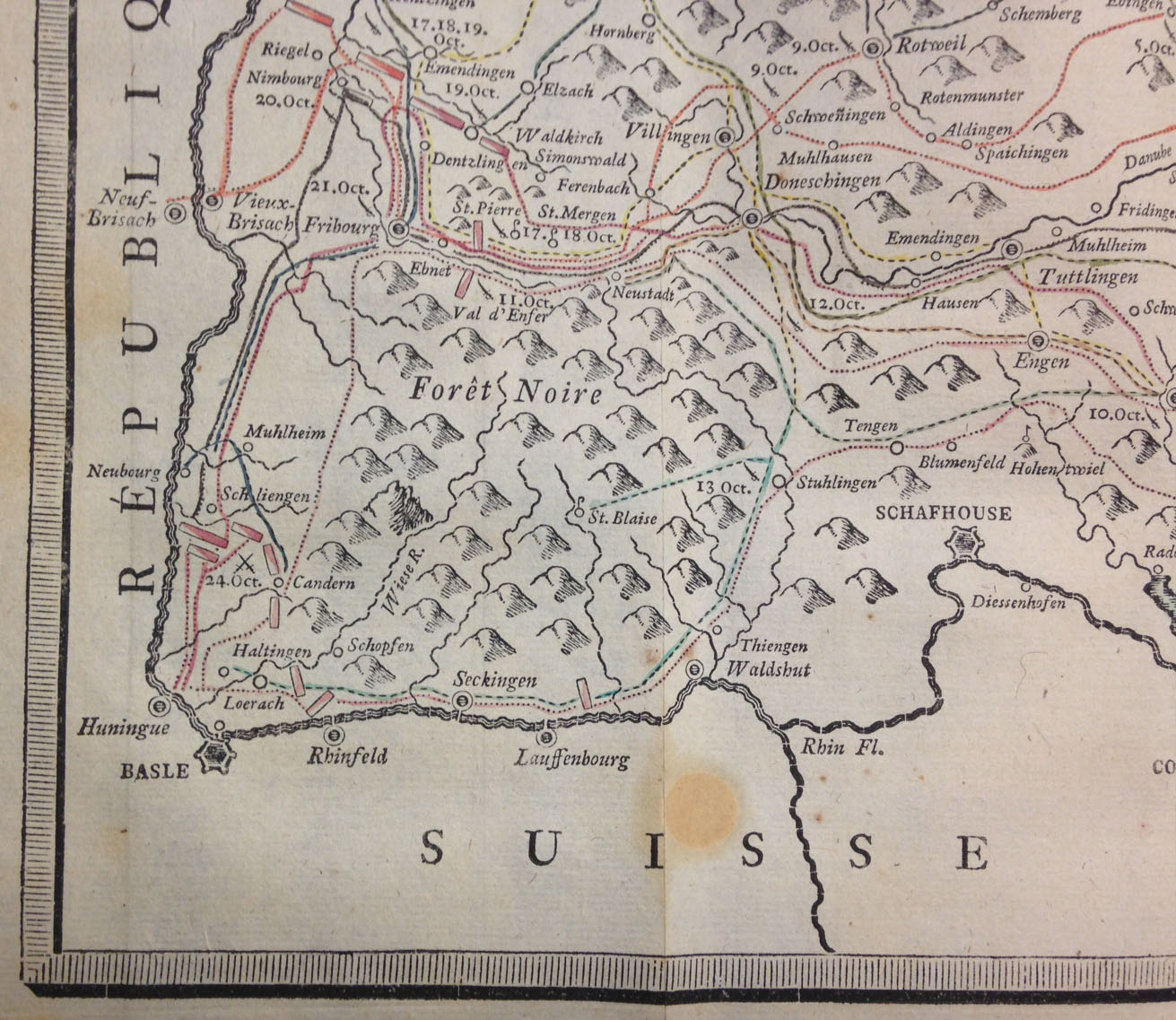

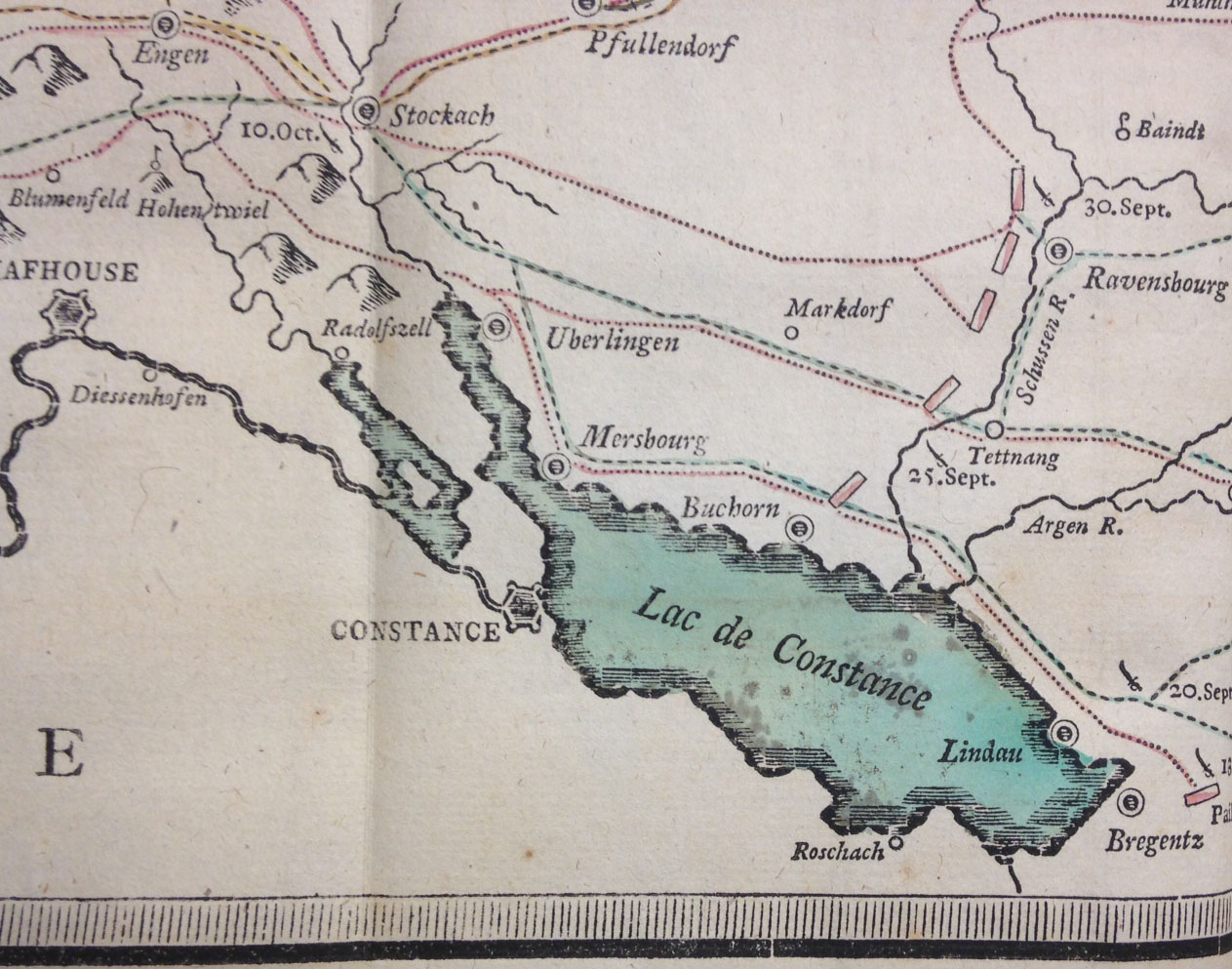

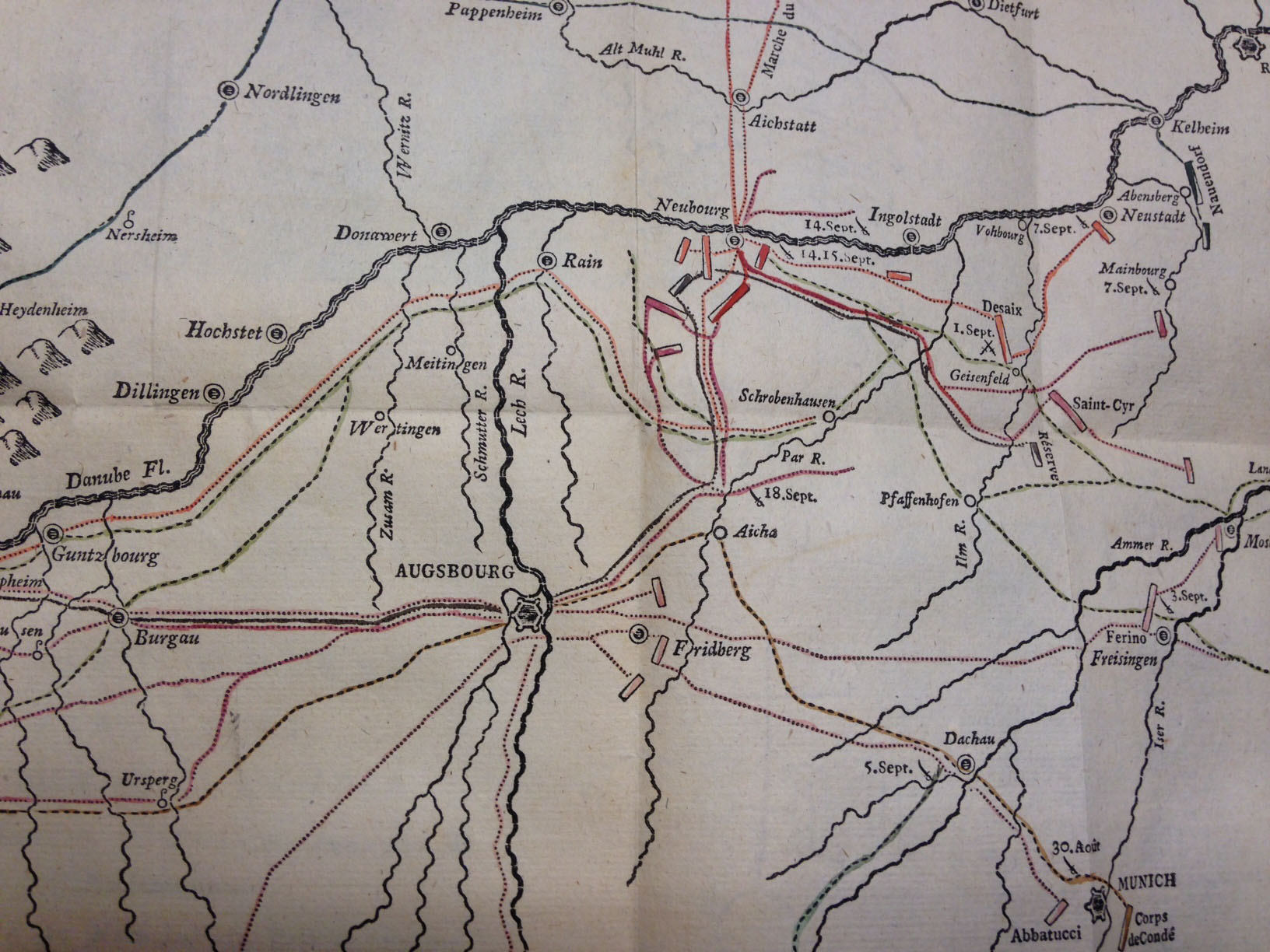

![The map, "composed with movable types," bears the imprint of G[uillaume, i.e. Wilhelm] Haas, the Basel [Switzerland] typefounder who cut and cast the special cartographic font.](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Map2.jpg)

![Public lands in Illinois: January 17, 1839 ... [Vandalia, Ill., 1839] (A 1839 .I55)](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/MG1.jpg)

![Augustus Q. Walton [i.e. Virgil Stewart], A history of the detection, conviction, life and designs of John A. Murel ... (New York, 1839) (A 1839 .W26)](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/MG2.jpg)

![The grant of the Venezuelian Emigration Company, with full explanation of their laudable object ... [St. Louis?, 1866] (A 1866 .G73)](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/MG4.jpg)