This week, we are pleased to feature a guest post from Stephanie Kingsley, a second-year Master’s student in the English Department at the University of Virginia. Ms. Kingsley specializes in colonial and 19th-century American literature, textual studies, and digital humanities. She plans to work in publishing and digital archives after her graduation in May 2014.

***

When I set out to find a literary work to edit for David Vander Meulen’s “Introduction to Scholarly Editing and Textual Criticism” course, I knew early on that I wanted to choose one which would allow me to utilize materials in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. I wanted to do an authoritative edition—an edition which established the author’s final intention for his or her work—and I knew that manuscript materials would be central to such a project. Little did I know that when I set this restriction on my choice, I would later be embarking on a full-blown bibliographical investigation.

I ultimately settled on Virginia author Ellen Glasgow. Many of Glasgow’s manuscripts, correspondence, and notes have come to reside in Special Collections, alongside those of many other Virginia writers; hence, I knew I would have wonderful resources at my fingertips in the course of the semester. After examining which works Special Collections had in manuscript, I selected In This Our Life, Glasgow’s final published novel, for my editorial project.

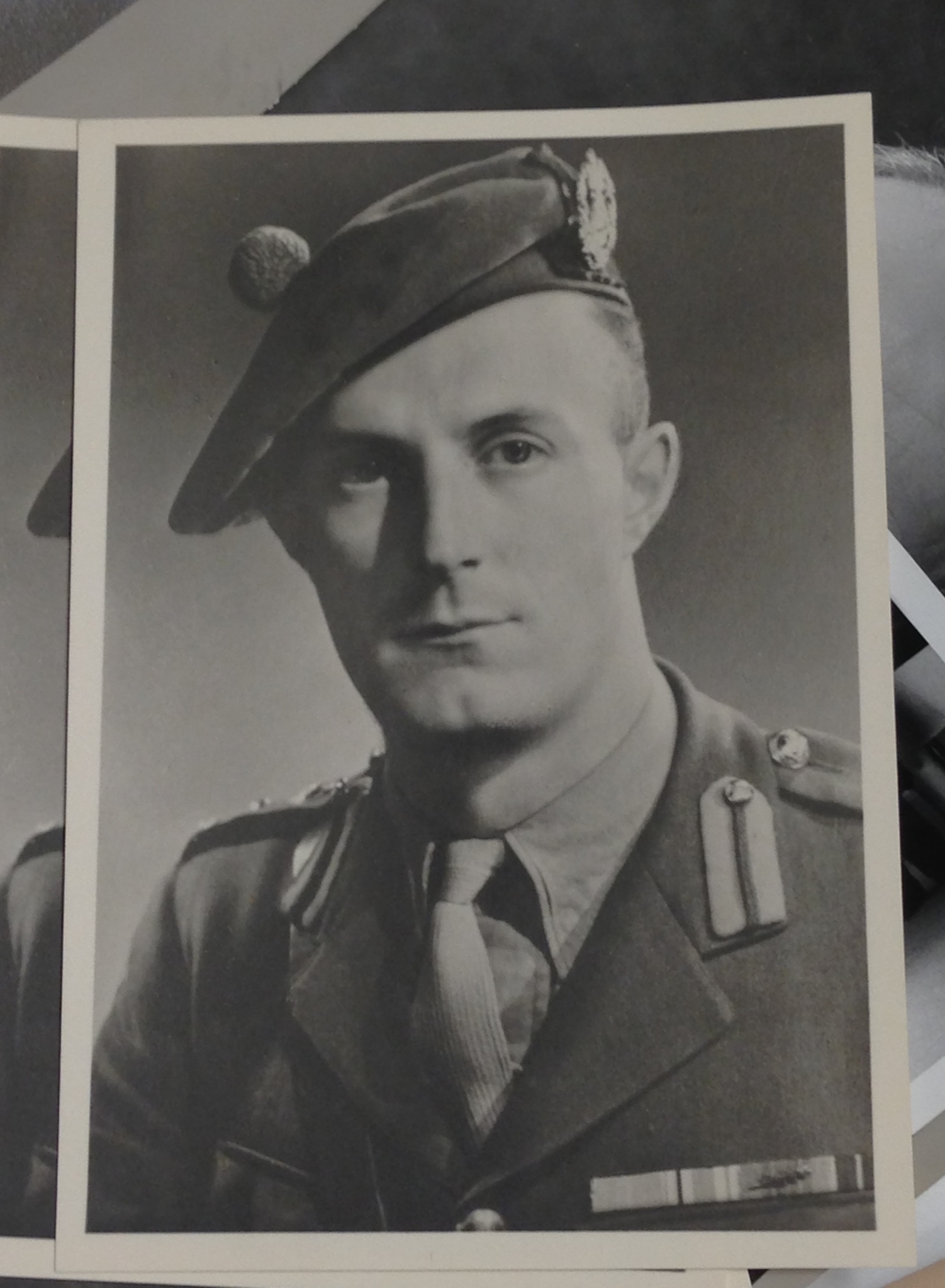

Photograph of Ellen Glasgow (1938) taken for her book The Woman Within (MSS 5060. Photograph by Petrina Jackson. Published with the Permission of the Ellen Glasgow Estate)

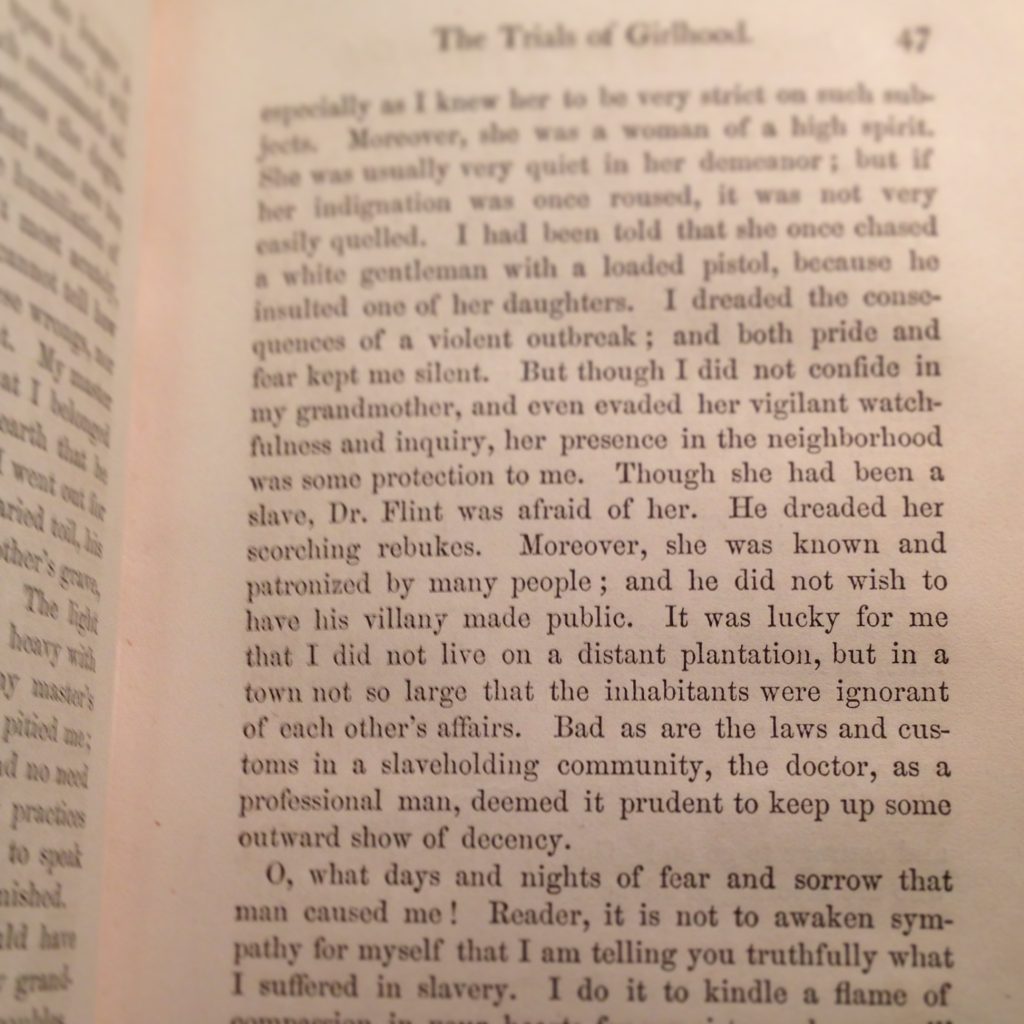

Ellen Glasgow was born in 1893, lived in Richmond all her life, and died in 1945. Glasgow is considered one of the most important Southern regionalist authors. Her novels address issues of class, gender, and race, hearkening back to the traditions of the agrarian Old South while acknowledging the advent of industrialism. Glasgow’s eighteenth and final novel, In This Our Life, focuses on a previously wealthy aristocratic family, the Timberlakes, as they sustain financial and family turmoil. For Glasgow, the family signifies both the changing times experienced by two distinct generations and man’s capacity never to accept defeat. Also prominent are issues of race, and special attention is given to the black Clay family serving the Timberlakes. In This Our Life garnered Glasgow the 1942 Pulitzer Prize for the Novel and was made into a film starring Bette Davis by Warner Brothers that same year. Belying these successes, the novel had a rocky beginning. Glasgow began planning it in 1935 and completed two drafts between 1939 and 1940, during which time she suffered a series of heart attacks. In her autobiography, Glasgow describes being able to write only 15 to 30 minutes a day during her illness, and in her preface to the novel, Glasgow laments not being able to complete a third draft as she usually did. Despite these hardships, Glasgow wrote, rewrote, and closely oversaw details of book design, jacket description, and publicity. In This Our Life was finally published in March 1941.

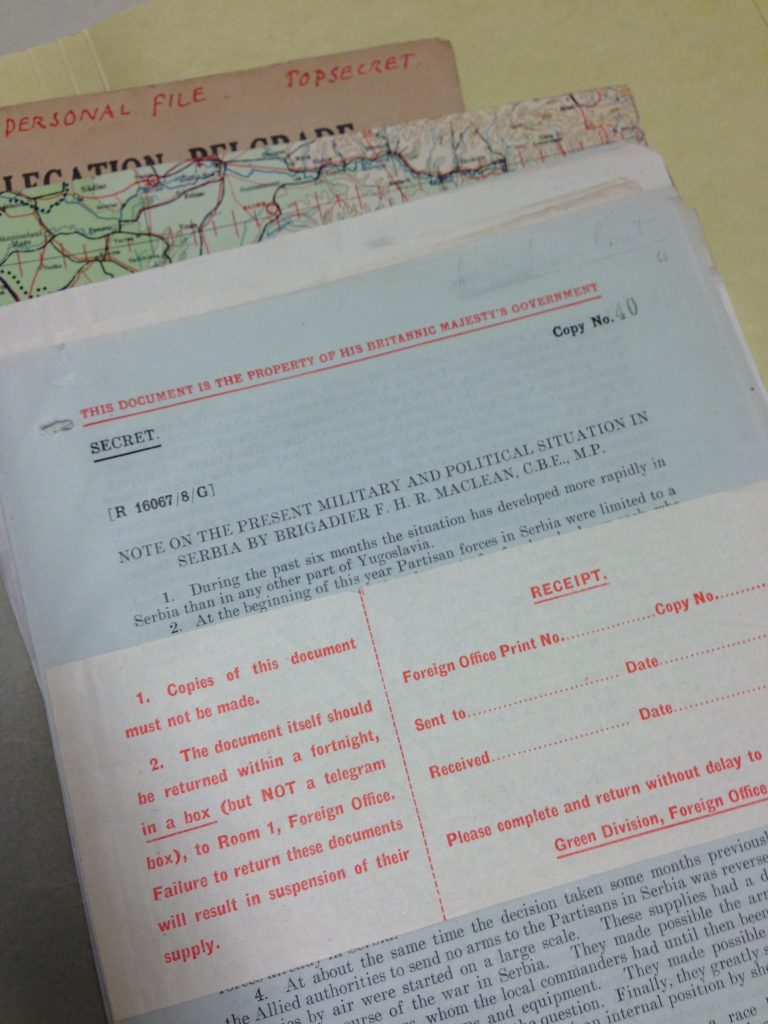

First Edition of In This Our Life, Harcourt Brace, 1941. (PS3513 .L34I5. Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature. Image by Petrina Jackson)

I felt that with such a fraught publication history, In This Our Life could surely use editorial work to determine whether Glasgow’s final intentions actually made it into the published novel. My first step was to consult the extensive Glasgow bibliography compiled by William W. Kelly in 1968 for the Bibliographical Society of Virginia. Kelly provides bibliographical descriptions of the early editions of Glasgow’s works, an in-depth history for each, and a list of manuscript materials available in Special Collections, many of which I would consult while preparing my edition.

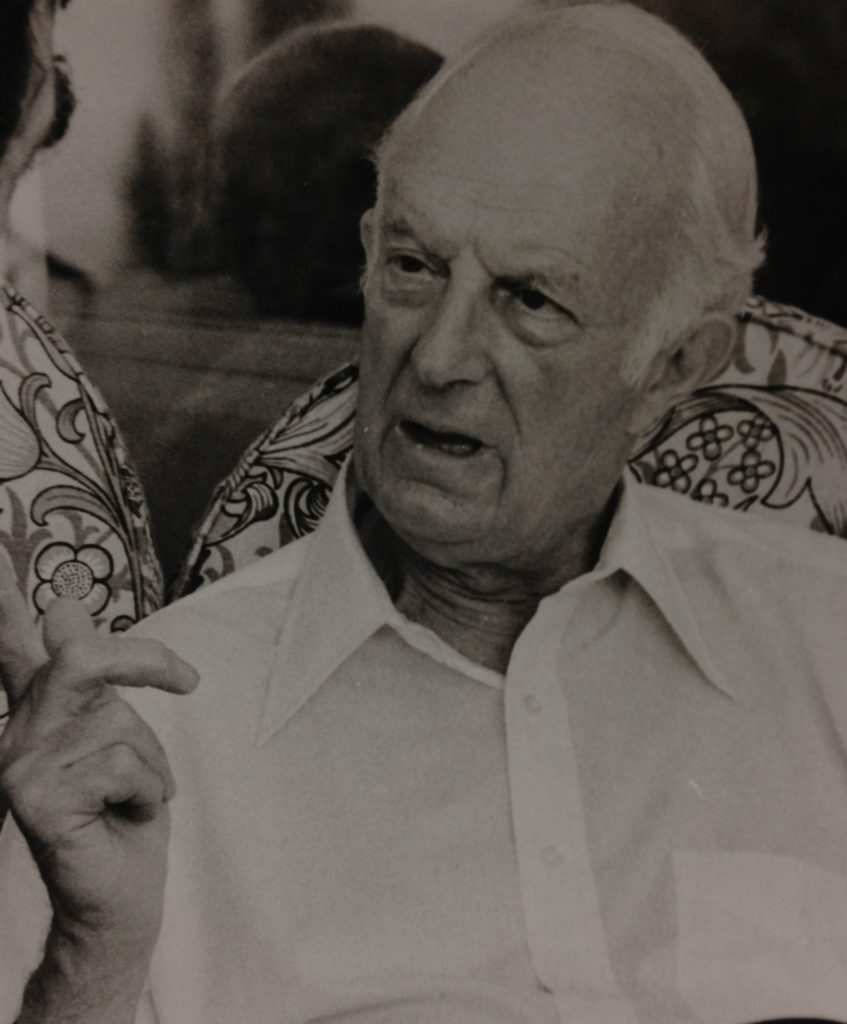

Portrait of James Branch Cabell, 1930. (RG-30/1/10.11) University of Virginia Visual History Collection. Online.

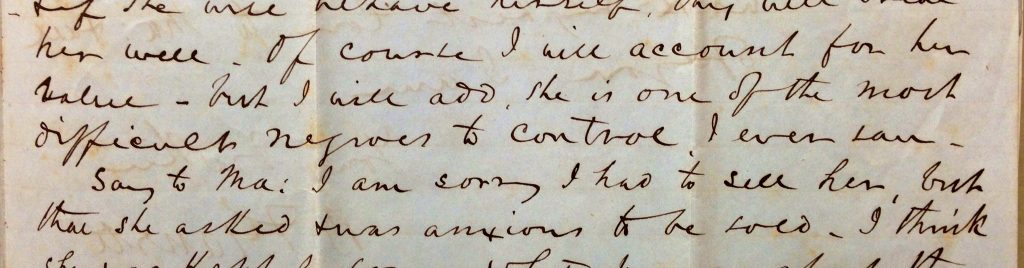

Kelly identifies an intriguing mystery in the publication history of In This Our Life. According to Glasgow’s close friend and fellow author James Branch Cabell, while she was ill during the late stages of writing In This Our Life, Cabell assisted by editing the typescript:

And now, upon the brink of triumph [winning the Pulitzer Prize], she was not bodily able to finish, or rather, to put into any acceptable shape, a final draft of the book which would ensure this distinction.

So I remedied affairs by doing this revising for her, in chief out of love and friendship and my honest sympathy, but in some part out of the derisive pleasure which I got from knowing that at long last I was completing a Pulitzer prize winner.

For this reasons then did I more than gladly give over some three or four months to In This Our Life, or to be more accurate, the afternoons of these months, because, in the mornings of them, I was drafting The First Gentleman of America….

…twice a week I would visit Ellen Glasgow’s sick chamber at about four o’clock in the afternoon, so as to show her what changes and slight amendments I was making in her text; and she, propped up in bed, wan and emaciated but as vigorous of mind as ever, would applaud them for the most part. She balked now and then, however, and as I thought ill-advisedly, over what she took to be a touch of the too frivolous or of the slightly risqué; for to my finding, this novel required a deal of animating; but meekly I would shrug and accept her mandates as to what, after all, was going to be her book, and not mine….

And after that, I would kiss her cheek and depart with a fresh batch of typescript for me to revise and to make tidy during the next three or four days. (Cabell, As I Remember It, 222-23)

Glasgow herself never mentions these revisions in either the preface to the novel or her autobiography. She recounts that Cabell spent hours by her bedside reading the typescript but says nothing of his editing. Furthermore, in the course of writing his bibliography, Kelly interviewed Glasgow’s secretary and companion, Anne Bennett, who called Cabell’s account a lie and said that he did not see the book until it was in page proofs. I decided to examine the typescript itself, over four hundred typewritten pages used by the printer to set the galleys, to see if it might offer any clues. And so my work Under Grounds began.

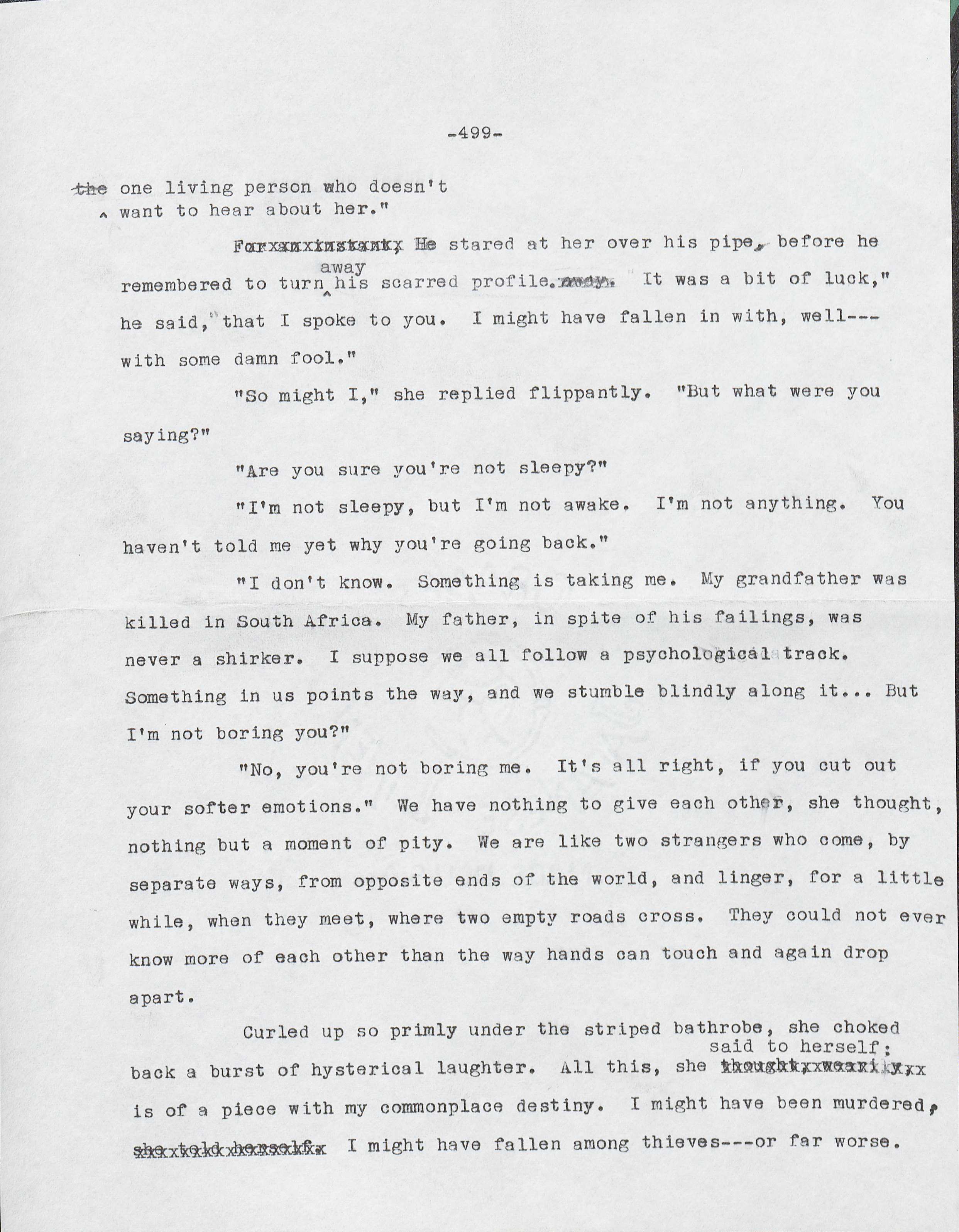

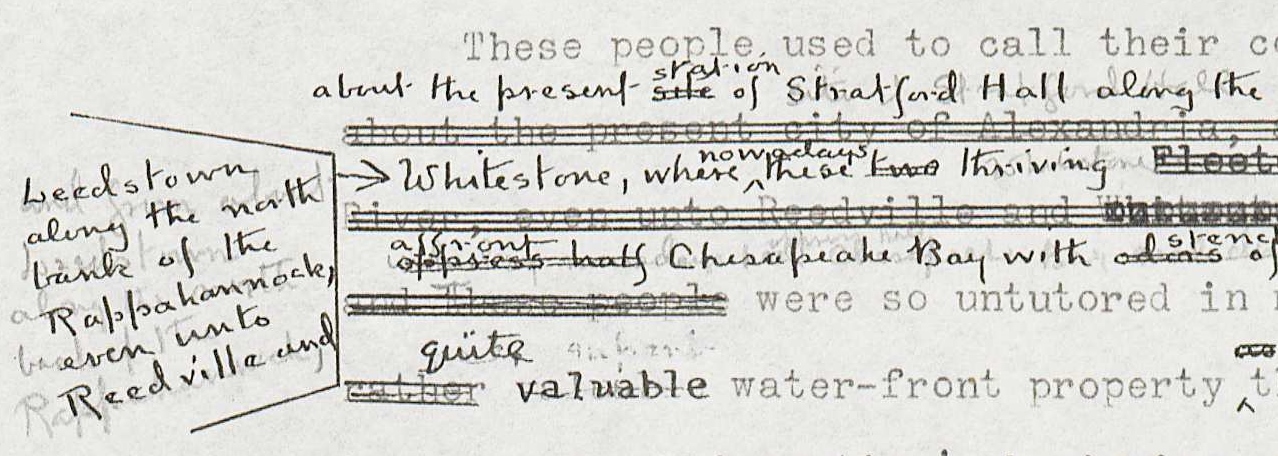

A sample leaf, page 499, from the typescript for In This Our Life (MSS 5060. Image by Petrina Jackson. Published with the Permission of the Ellen Glasgow Estate)

As the typescript was central to my editorial work, I set out to confirm that it and the revisions on it could be considered authoritative. Revisions included reworked passages in type and minor punctuation corrections in pencil. Because the most extensive edits were in type, I assumed that if Cabell did edit the typescript, he did so with his typewriter. At the recommendation of Professor Vander Meulen, I proceeded to compare types in hopes of identifying distinct typists.

The first problem with respect to typescript authority was the matter of who typed the typescript. In her letters, Glasgow describes it as a fair copy transcribed by Anne Bennett. By comparing the types of the running text and revisions to other Glasgow materials, such as pre-draft notes and earlier page states, I was able to identify two different typewriters involved: the one responsible for the running text was Bennett’s, and the revisions were by Glasgow’s.

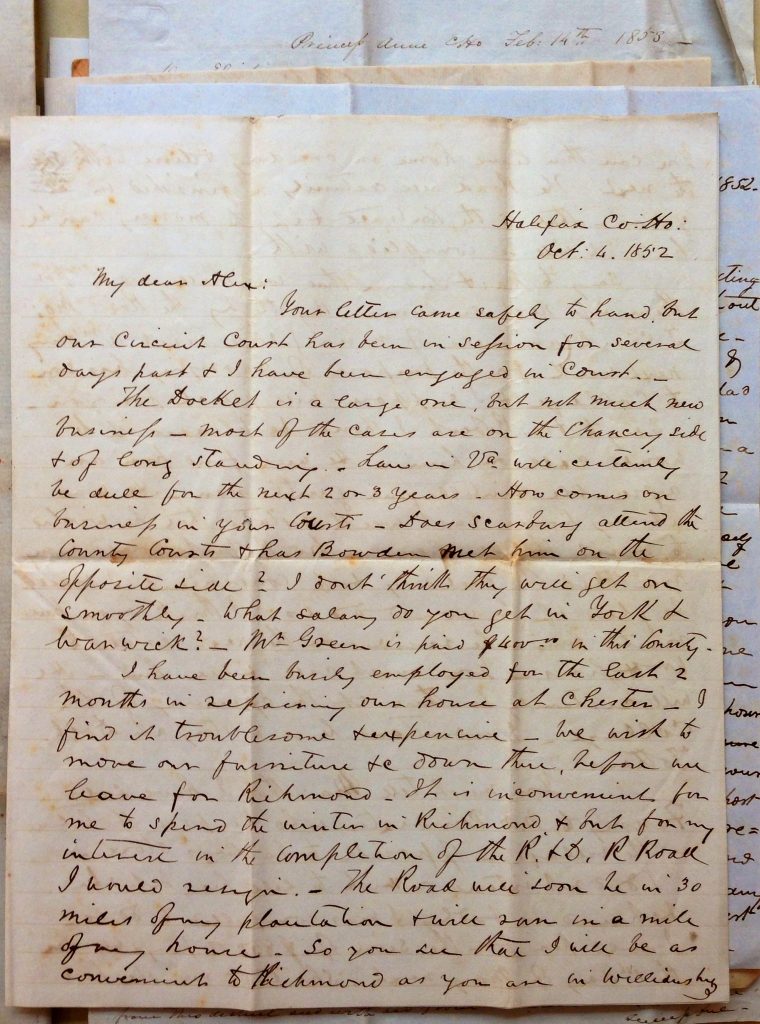

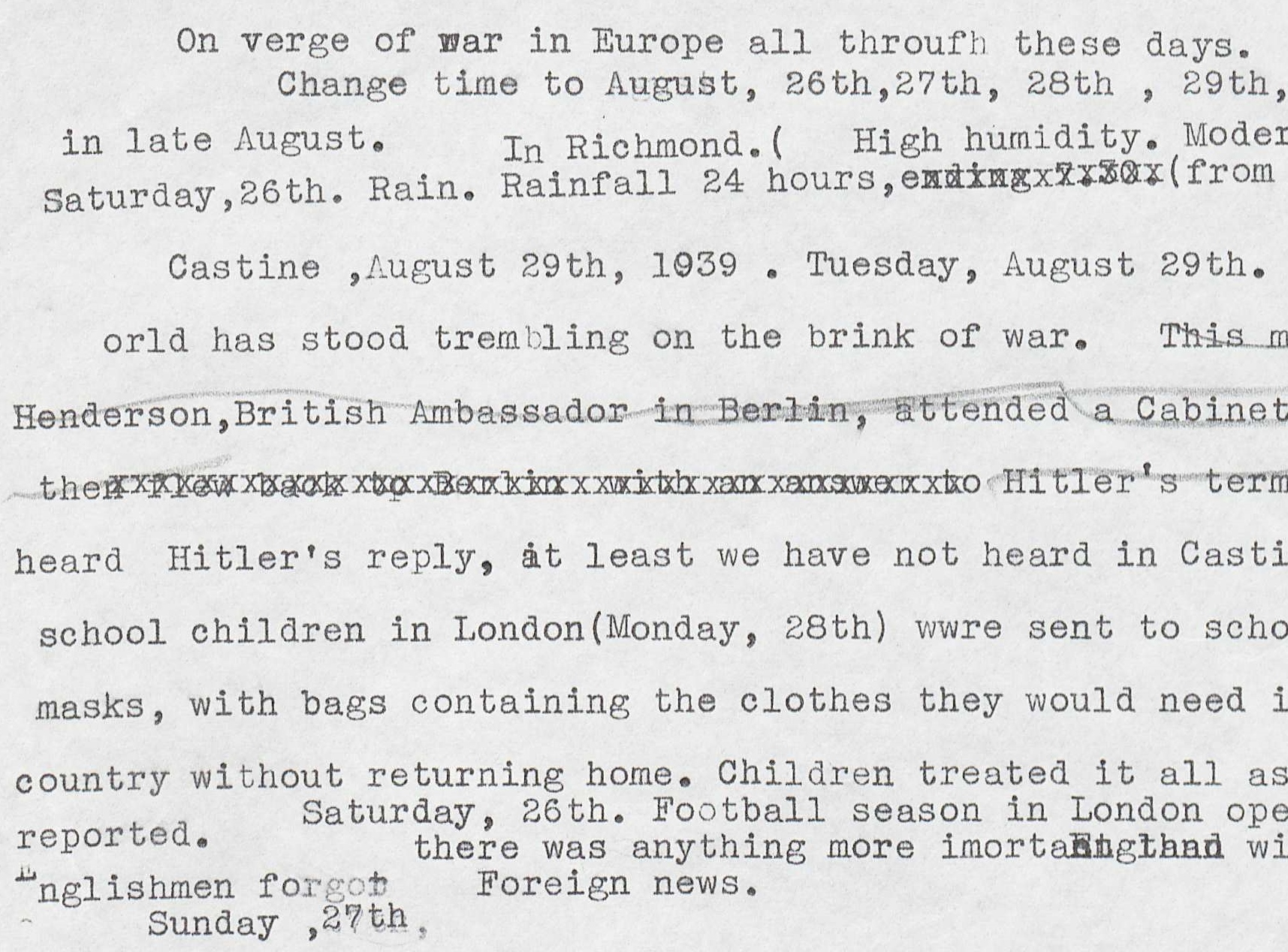

Detail of page 499 of In This Our Life’s final draft typescript. An example of type revisions made on Glasgow’s typewriter can be seen on the first line of the page. Notice how the “t” in “the” has a wider bottom than the “t” in “want” in the line of running text below. The wide “t” was a distinguishing feature of Glasgow’s typewriter, while the narrow “t” was characteristic of Bennett’s. It appears that the two women had the same sort of typewriter, but subtle variations in type such as these enabled me to differentiate. (MSS 5060. Image by Petrina Jackson. Published with the Permission of the Ellen Glasgow Estate)

Detail of leaf one of Glasgow’s pre-draft notes for In This Our Life. Notice how the “t’s” on Glasgow’s notes are wide. As Glasgow herself would have authored the notes, I compared types from them to the final draft typescript in order to identify Glasgow’s typewriter. (MSS 5060. Image by Petrina Jackson. Published with the Permission of the Ellen Glasgow Estate)

It appears that Glasgow’s habit was to type earlier drafts herself and then have Anne Bennett prepare fair copies for further revision. Thus, type comparison enabled me to reconstruct the process of Bennett’s transcription and Glasgow’s revision. I also could conclude that Cabell did not make these type revisions in his afternoon editing sessions at home. However, I was still not perfectly satisfied with respect to the Cabell editorial mystery. Nor could my findings account for the pencil markings occasionally deleting or inserting commas. Lastly, I still had utterly competing secondary accounts. I decided to describe the question as an open case in the introduction to my edition, and thus finish my project.

A few days before I was to turn in my edition, I found that—like any good student of bibliography—I was still perturbed by those pencil corrections. I felt that I was missing something, so I descended Under Grounds for another look. After several weeks away from the typescript, a fresh glance revealed that the minor pencil corrections were not the only handwriting on the typescript: remnants of erased handwriting could be discerned throughout, editing not only for punctuation and capitalization but also for wording. I was astounded. I had been assuming all along that Cabell had edited with a typewriter, if at all, and had never considered written corrections, simply because with the exception of a few commas and stray words, they had been utterly obliterated.

I knew what I had to do. Cabell mentioned working on The First Gentleman of America while editing In This Our Life, and as it turned out, Special Collections also had the typescript for this work—with written revisions in Cabell’s hand! The night before my edition was due, I was in Special Collections again examining the handwriting on the two typescripts, and after scouring the Glasgow pages for writing which was clear enough for comparison to Cabell’s hand, I concluded that the hand was indeed his. In the photographs below of the two authors’ typescripts, you’ll easily discern that the handwriting is from the same person.

Detail of page 382 of the final draft typescript of In This Our Life, page 382. (MSS 5060. Image by Petrina Jackson. Published with the Permission of the Ellen Glasgow Estate)

Detail of Cabell’s First Gentleman of America typescript, page 1. (MSS 5618. Image by Petrina Jackson)

It appears that Cabell revised the typescript in pencil; then after he, Glasgow and Harcourt-Brace had decided this draft was ready to go to the printer, Glasgow went back, reviewed and retyped Cabell’s revisions, and erased his handwriting—probably in an effort to make the revisions as clear as possible for the printer.

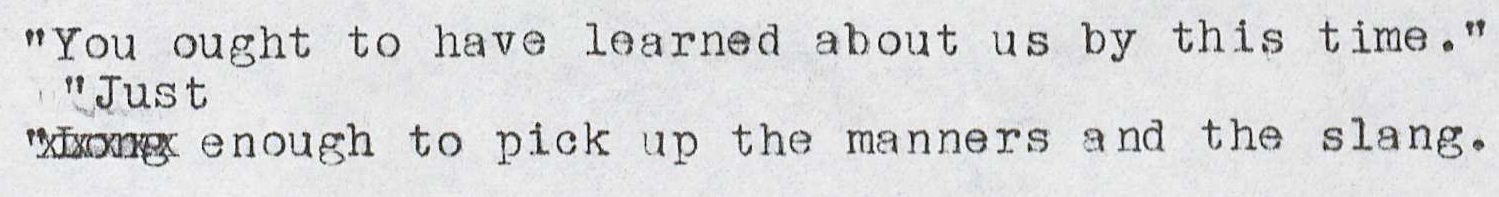

Page 489 of In This Our Life typescript. See how the word “Just” is handwritten, erased, and then typewritten. (MSS 5060. Image by Petrina Jackson. Published with the Permission of the Ellen Glasgow Estate)

From reading what little handwriting remains, it appears that Glasgow did approve and adopt most of Cabell’s revisions. She also added revisions of her own, apparently using preparation for the printer as an opportunity to do final revisions which she had not gotten to do before. Another possibility, however, is that Cabell sat by Glasgow’s bedside and, while reading his changes to her, typed over his handwriting with Glasgow’s typewriter for the same purpose: to make it clear for the printer. This part of the typescript’s history yet remains obscured, and a scholar of both Glasgow and Cabell’s literature would need to analyze the places where the type revisions deviate from the handwritten ones to judge whether they were more likely the result of the two authors’ collaboration or Glasgow’s emendations alone. This typescript has revealed much and may yet have more to say about the relationship of these two authors and their creative process. It simply takes an intrepid spirit sallying forth into Special Collections to make it speak!