This week we are pleased to feature a guest post from Harrison Fellow Lauren LaFauci.

Dr. LaFauci spent several weeks in Special Collections this spring as an Elwood Fellow at the Harrison Institute for American History, Literature, and Culture. She was researching for her current book project, entitled Peculiar Natures: Slavery, Environment, and Nationalism in the Southern States, 1789-1865. She teaches at the University of Tulsa.

A tireless researcher who dug deep into our collections, LaFauci generously shared her most interesting finds with the Reading Room staff. She agreed to write for Notes from Under Grounds about one item in particular: a letter from a slave-owner describing how he came to sell his his slave Fanny. As LaFauci points out, we can only get so far in recovering the circumstances of this sale since this letter is our only source.

***

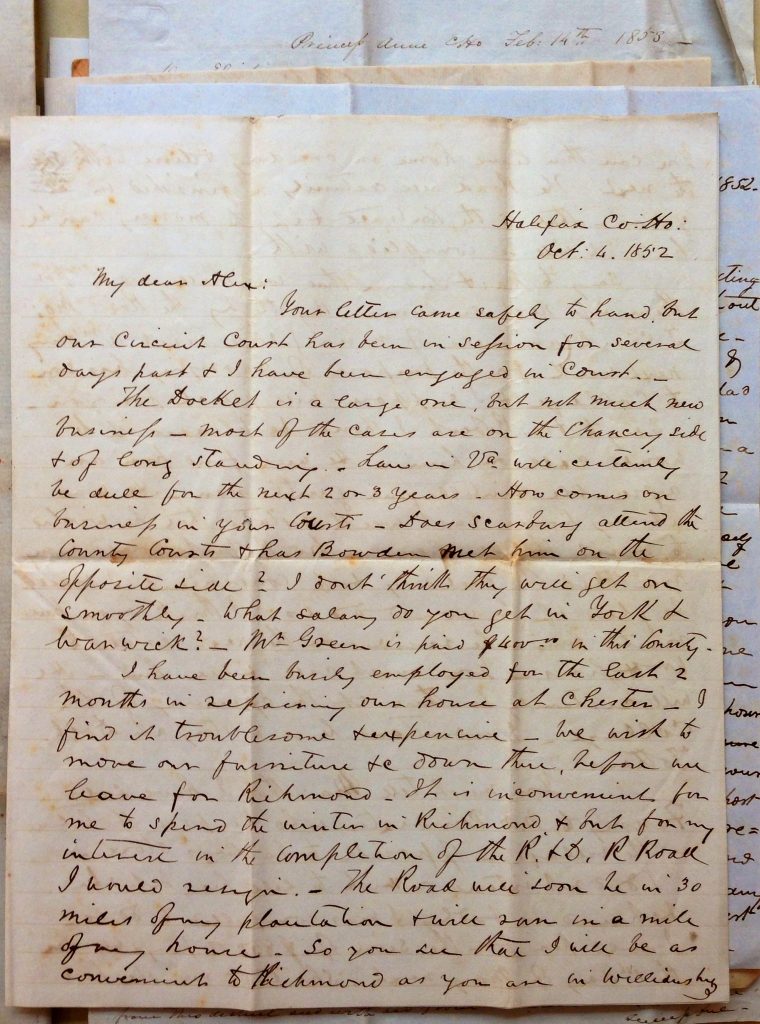

Writing from Halifax Court House, Virginia to his brother Alex in Williamsburg on October 4, 1852, Ben Garrett closed his letter with the following important news:

You must tell Ma : that I have sold Fanny to Mr Poindexter who Keeps a Hotel in the village – opposite to Easley’s store – I did not intend or wish to sell her, but she behaved so badly I was compelled to do so – I sold her for the sum of $850.00 payable on the 1st day of May next –

Such a note—while always jarring to 21st-century readers, even to those of us reading about and studying slavery—communicates nothing unusual to its recipient. Citing what he perceived as Fanny’s bad behavior, Ben told Alex that he “was compelled to [sell her],” which was a common punishment. However, the rest of the letter communicates something highly unusual, at least for those stories preserved in the archive:

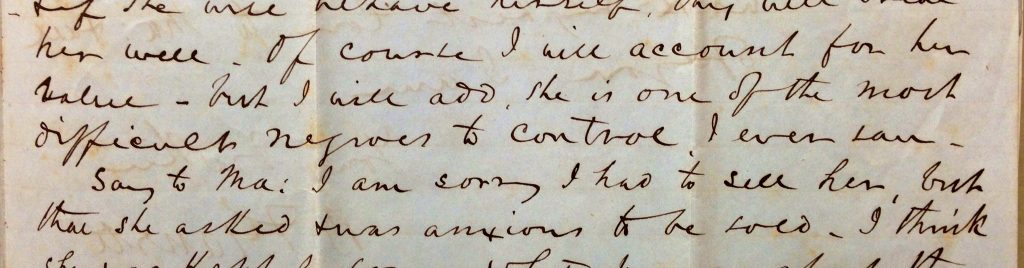

She told me, she had rather be sold than to go back to Williamsburg You know I disposed of my home & lot at the Co: House & determined to remove to my plantation sometime in November next. She was opposed to living in the Country – not wishing to leave the Village I told her to go to the plantation, whereupon she ran off from me & was gone a week. – When she came home, she said, she wanted to be sold & that “arrangements” were made the night before she returned home for her to get off to a free State or out of the State, but that she preferred being sold in the Village – I have had a deal of trouble with her – more than all the rest together for it was almost impossible to control her. She exhibited no signs of penitence & asked me to sell her. Poindexter offered me a large price & I determined to let her go – I understand that he & his wife are pleased with her & if she will behave herself, they will treat her well – Of course I will account for her value – but I will add, she is one of the most difficult negroes to control I ever saw –

Say to Ma : I am sorry I had to sell her, but that she asked & was anxious to be sold – I think she was Kept by some white persons about the Village, which was the cause of her conduct. I saw her to-day & she seemed to be satisfied with her new home from her appearance — I know that she was treated well at our house & there was no excuse for her behaviour & then to have the impudence to run away from me & stay out a week. If it was not that she was aunt Lucy’s child (who has been so faithful) I should have no pity for her – [. . .]

This story presents a number of thorny questions. If we take Ben’s communication of the events at face value—a large “if,” and more on that below—then Fanny took distinct and savvy actions to achieve her desired outcome. First, she resisted Ben’s orders to “go to the plantation” in the country by running away for one week; at that time, she may have been making the “arrangements” Ben alludes to. Such truancy would have signaled to Ben that she was willing to take drastic actions in order to get her way, while simultaneously giving her time and space to effect her own escape or sale. Second, she appears to have negotiated this sale; Ben notes that Fanny “asked & was anxious to be sold” and that she “was opposed to living in the Country” and would “rather be sold than to go back to Williamsburg.”

These lines from the third page of the letter reveal the extent of Fanny’s influence upon her owner. (Photo by Molly Schwartzburg)

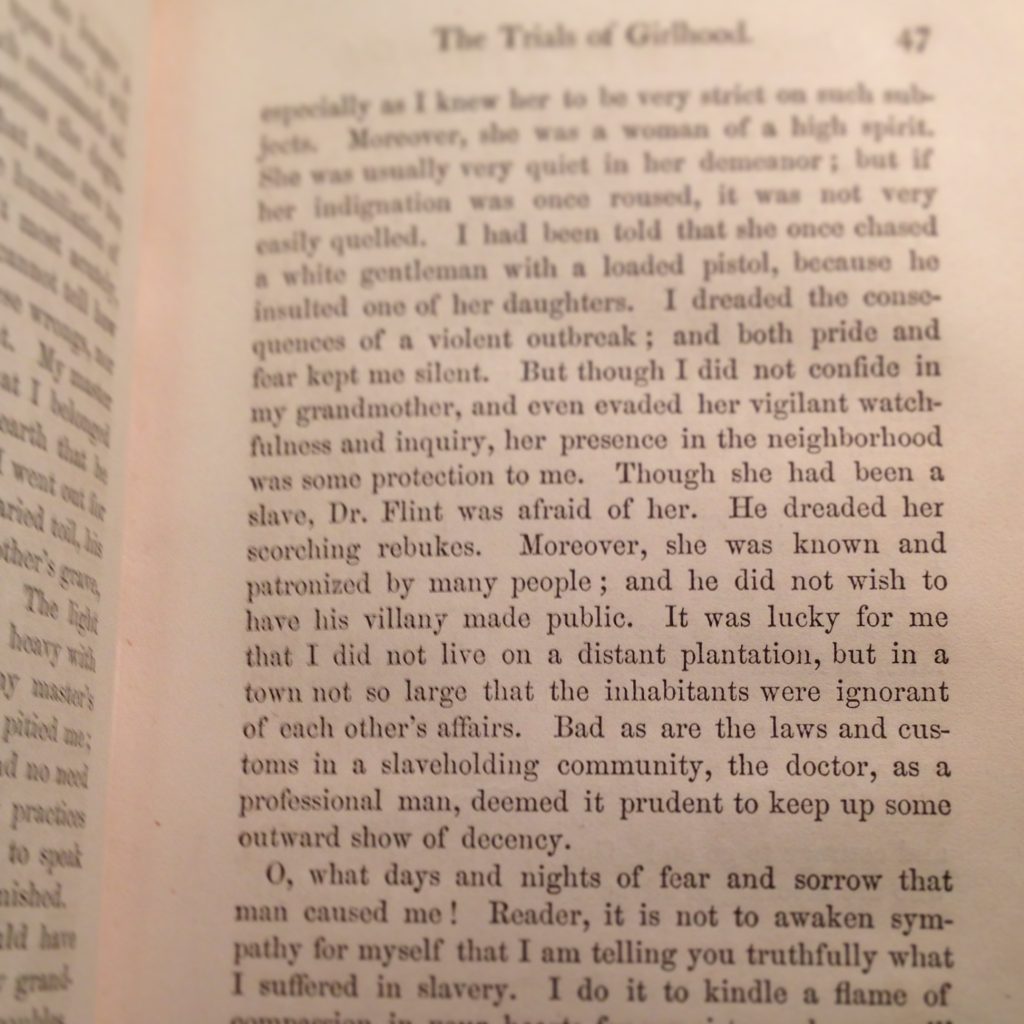

If we assume Ben’s version of events, Fanny told him that she preferred to be sold “in the Village” rather than relocating to his rural plantation. Such a preference raises an intriguing parallel to the narrative of Harriet Jacobs, who similarly desired to stay within the town of Edenton, North Carolina, where she gained some protection from the advances of her lecherous owner, James Norcom: “It was lucky for me that I did not live on a distant plantation,” she wrote, “but in a town not so large that the inhabitants were ignorant of each other’s affairs. Bad as are the laws and customs in a slaveholding community, [Norcom], as a professional man, deemed it prudent to keep up some outward show of decency” (47).** In another parallel with Jacobs, Fanny appears to have been on intimate terms with “some white persons about the Village”: readers of Jacobs will recall that she forms a relationship with Samuel Tredwell Sawyer, having two children with him, in order to protect herself from the sexual advances of Norcom. Both Fanny and Jacobs seem to engage in alternative relationships to gain increased power within a system designed to deny them such agency.

A page from Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, demonstrating compelling parallels with Fanny’s much more heavily mediated story. (PS 1293 .I54 1861. Photo by Molly Schwartzburg)

And now to that big “if” – to what extent can we take Ben’s account of this story as “the truth”? If Fanny was indeed seeking shelter from sexual advances, can we trust that she really “asked & was anxious to be sold”? Or was Ben trying to cover for himself, to provide a reason for the sale of an enslaved woman who was clearly important to the family?

These questions, among many others, make up the central problem for historians of slavery: most of the stories about enslaved people in the archive are mediated through the voices of the people who legally owned them. We attempt to ascertain the “true” course of events, but we must frequently do so through the words of those with the power to construct such stories however they wish, and for audiences with motivations similar to their own. In a time when enslaved people were prohibited by law from learning to read and write, any evidence of literacy would have been hidden from those with the power to preserve such words, leaving us with mere traces and glimpses. We work through several layers of meaning, only to emerge with more questions than we had at the start. How do you interpret Fanny’s story?