This week, we are pleased to feature a guest post from researcher Brenda Fredericks. Mrs. Fredericks is an independent scholar researching her family’s genealogy. She spent number of days studying the David Molloy Gannaway Papers.

My trip to the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library on October 22, 2015 was one of great anticipation. Six months prior, I did an internet search and found that this institution had in its holdings original letters of Burrell Gannaway, a former resident of Buckingham Count, VA. This man was the enslaver of my husband’s ancestors.

These ancestors are the family of celebrated African American Photographer, King Daniel Ganaway. My husband Tim is his great-grandson. Note: The spelling of the last name differs between the slave owners and the African Americans. The slave-holding family uses Gannaway, while the African American family members use Ganaway.

I was perplexed as to how or when we would be able to make the trip to the library. Most of my time off from work is used to care for Tim, who has been a bladder cancer patient for the last two years. After visiting the website and learning there were more than 1,000 documents on the Gannaway family held at this library, I knew we had to make the trip. These letters could possibly give us a window into the world of our ancestors.

On September 29th, I was among 300-plus employees who were laid off from my company. There was severance pay attached to the lay-off. While others fretted about their disposition, I smiled. We had just been given our opportunity to come to Virginia!

The Gannaway family settled in Albemarle and Buckingham Counties in the 1700’s. They were prominent in the communities where they lived and owned quite a number of slaves. John Gannaway III and Martha Woodson Gannaway were the parents of Burrell as well as six other children.

As I set at one of the tables in the library, I knew this would be a day I would never forget. Box after box was brought out to me, containing letters, accounting records and deeds, belonging to the Gannaway family. At first my hands shook as I picked up each one. What is the likelihood that an African American in 2015 would one day hold in her hands the original documents of her ancestors’ enslavers?

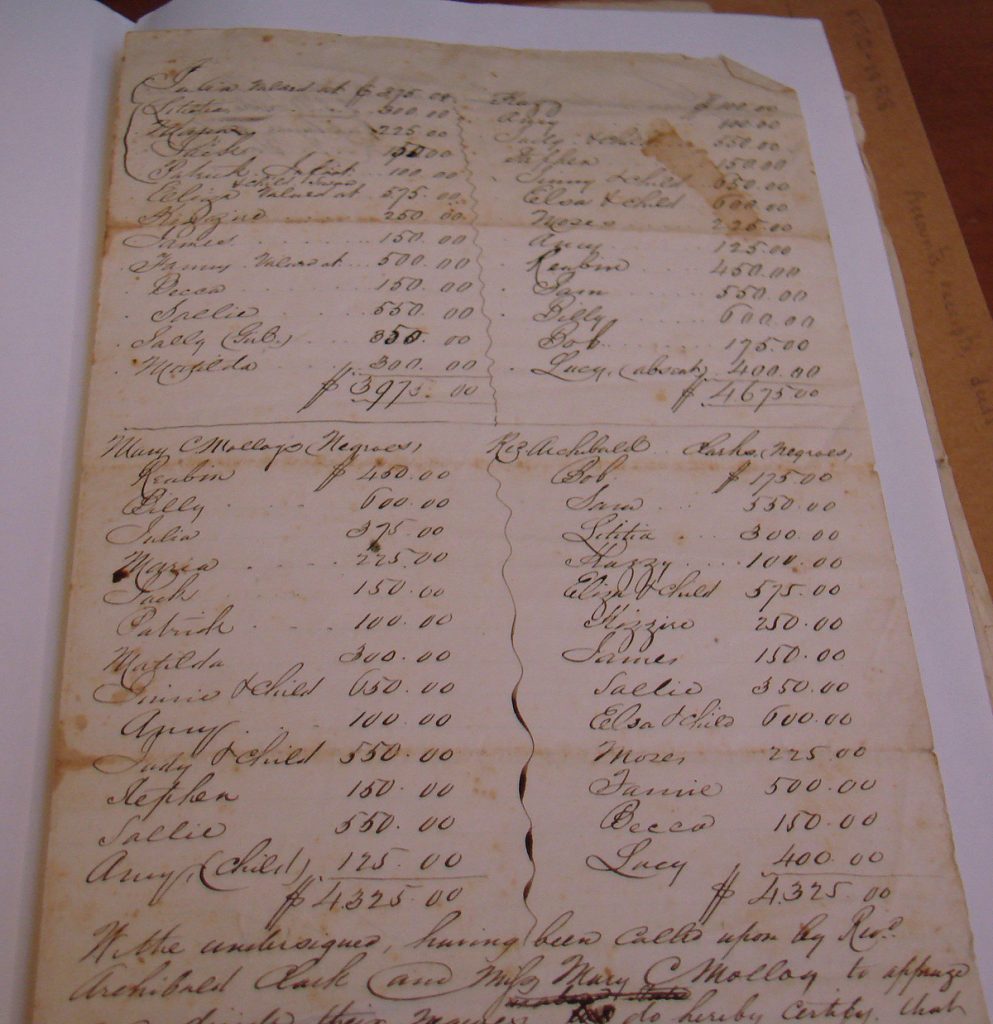

The first item that caught my attention was a list of slaves.

Here they were! These are our people and possibly other slaves who were related to them. Judy, America, Bob, Amy and Tom would ultimately make their way to Murfreesboro, TN where Burrell Gannaway and his married sister Mary Molloy relocated around 1814. The thought came to my mind that they were more than likely separated from family. This means that their descendants are still separated from our family to this day.

There was a value given to each slave. Although it was a reality during slavery to place a value on African Americans, my mind simply cannot process this information. Nevertheless, the names on this list were some of the same names found in Burrell Gannaway’s estate inventory when he died in 1853.

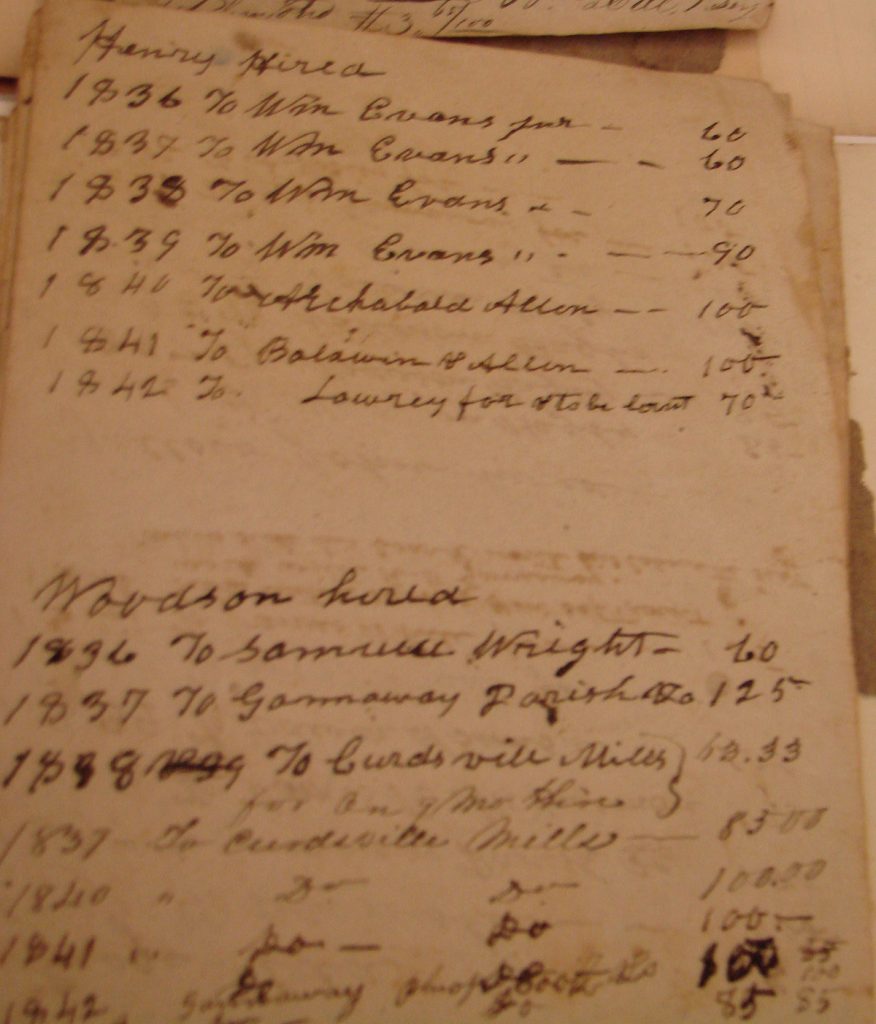

As I continued to browse through the documents, I came across accounting records that concerned a mill in Buckingham County referenced to as the Curdsville Mill. I knew about this mill from other historians’ research. Enslaved people likely supposedly built this mill, which is located on the Willis River.

Slave hire document, David Molloy Gannaway papers, ca. 1836-1840s. This document records the names of slaves being hired out to work at Curdsville Mill (MSS 3784). (Photo by Brenda Fredericks)

I also noted from this document that Woodson was also hired out to Gannaway and Parish Co. The name Parish was one I was familiar with. I knew from old newspaper articles that this family had been in business with the Gannaways in Virginia, and here was the proof.

My husband and I later drove to Curdsville and found the ruins of this mill!

Of course any letter that Burrell wrote is of keen interest to me. In a March 1834 letter, he explains his political views to his brother Theodorick (Gravel Hill):

“I am for measures best for the Republic and for myself on this subject I am pointed and my mind made up. I am in favor of our union and all and every measure calculated to perpetuate the union.”

This letter along with others found at the State Library in Richmond show a transformation from an ambitious southern planter to a man beaten by illness, disease, loss of family members and bad crop seasons. He ultimately turns to his faith in God which gives him peace and hope.

Burrell Gannaway had been dead for 12 years when the Civil War ended in 1865. However, he must have left an indelible mark on his friends and business associates because they gave assistance to his former slaves. Daniel Gannaway, the grandfather of King Ganaway, purchased a merchant bond in 1872 and opened a grocery store on the town square in Murfreesboro. Remember those old Virginia business partners by the name of Parrish? They sold land to our Ganaways near the family store. King Daniel’s father and grandfather built a large family home on this land that stood there until the 1950’s.

After the war, Burrell’s congregation, First Baptist Church of Murfreesboro, sold their old church building to the former slaves to start their own church. Some of these slaves were our Ganaways. They had attended services with Burrell where he was a founding members and one of the first deacons. King Daniel’s paternal and maternal grandmothers were Church Mothers of the African American First Baptist congregation.

By no means is Burrell Gannaway the hero of this story. The man I’ve come to know in his letters would not want that credit. It is the God who Burrell wrote about and his relative Annie M. Gannaway who preserved these letters and donated them to this institution who are heroes!