Earlier this spring semester, about 40 undergraduates from Allison Wright’s media studies course Sports, Media, & Society came to Special Collections Library for an orientation on finding primary sources. They were preparing for an assignment that required them to select a primary source and write a paper analyzing its sociohistoric context and relationship to topics covered in class. Out of the class, six of the student papers rose to the top, so we are featuring them to show their great work!

You may ask, what separated their papers from the rest? According to Dr. Wright, who is also the Assistant Editor of the Virginia Quarterly Review, it was their level of analysis and application of good investigative journalism that made these papers strong ones. She emphasized that they did good hands-on research, but also clearly integrated primary sources with quality secondary sources. They went beyond the basic class framework and requirement of the assignment and applied critical thinking skills especially well.

Now check out these fabulous students!

Allison Wright and her students Chris Wood, E.P. Stonehill, Robbie Kemp, and Patrick Schuler (left to right). April 8, 2013 (Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Students Charlotte Clarke and Kayleigh Hentges pictured with their instructor Allison Wright (on the left) round out the group with superior essays.

Let’s take a closer look at their work.

Chris Wood’s “The End of Black Jockeys”

Not all primary sources are accessible on paper: many of them have been provided in a digital format. That is the case with Fourth-Year student Chris Wood’s choice of Goodwin’s Official Turf Guide, a publication for those interested in horse racing, particularly jockeys and racing associations in the U.S. and Canada. Wood’s selection is not from the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, but it is an example of how these types of materials can be accessible via the Internet. In this case, it is accessible via the HathiTrust Digital Library.

Chris Wood, Fourth-Year student, displays Goodwin’s Annual Turf Guide. (Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Excerpt from Chris Wood’s “The End of Black Jockeys”:

Close examination of Goodwin’s Official Turf Guide displays a lack of African American jockeys in the early twentieth century. Goodwin’s Official Turf Guide was the most respected guide to horse racing during this time period and contains information regarding jockey mounts, horse deaths, weight limit rules, gambling guidelines, and other horse racing information from the period. It was published semi-annually, with the second volume always containing the full information from the past year. Comparing the names of jockey mounts from 1905-1908, I found that only the 1907 guide lists more than one black jockey (Goodwin’s). The only two African American jockeys whose names are included in Goodwin’s are Dale Austin and Jimmy Lee (Goodwin’s). Considering that in the first Kentucky Derby, fourteen out of fifteen riders were black and that fifteen of the first twenty-eight Kentucky Derbies were won by African Americans, there must be a reason for the lack of black jockeys listed in these four years of Goodwin’s Official Turf Guide.

E.P. Stonehill’s Whitewashed Columns

Elizabeth (E.P.) Stonehill, Fourth-Year student, selected an editorial column from a 1968 Cavalier Daily (student newspaper of the University of Virginia) to explore the University’s resistance to black athletes after the end of segregation. The column she used was part two of an editorial/article by Bob Cullen in “The Sports Scene” titled “Orange, Blue, and Lily White II.”

E.P. Stonehill, Fourth-Year student, pictured with Special Collections’ bound copy of the 1968 Cavalier Daily. (Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

The central piece of Stonehill’s essay is Bob Cullen’s article from the Cavalier Daily, entitled “Orange, Blue, and Lily-White.” November 5, 1968. (Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Excerpt from E.P. Stonehill’s “Whitewashed Columns”:

In 1968, the Olympic Project for Human Rights [OPHR] threatened to boycott the Mexico City Olympics as a denunciation of racism within sports and society. Specifically, OPHR focused on the plight of the black athlete. Print journalism, in publications such as Life and Sports Illustrated, featured the issue prominently and thus garnered it international attention. Nearly 2,500 miles away in Charlottesville, Virginia, issues surrounding the black athlete took on a salient position–or, technically, a lack thereof. Indeed, The Cavalier Daily, the University of Virginia’s student newspaper, ran a two-part series entitled “Orange, Blue, and Lily-White” in its Sports section between November 4 and 5, 1968. The articles, written by Bob Cullen for his column “The Sports Scene,” criticize the University’s systemic racism and espouse the need to recruit black football players and coaches. Although comprising only two columns of text, Cullen’s articles reflect the national focus, particularly within print journalism on black athletes. By framing black athletes within the whole university culture, Cullen’s articles additionally highlight the inherent inability to separate politics from sport and the gradual nature of athletic integration.

Robbie Kemp’s “Sampson’s Lasting Legacy”

Fourth-Year student Robbie Kemp chose two Sports Illustrated articles to examine U.Va. alumnus and basketball great Ralph Sampson’s role as an athlete and a college student. Kemp stated that this assignment exposed him to paper sources again, instead of relying so heavily on databases and proxies as he had become accustomed to doing.

Robbie Kemp, Fourth-Year student, pictured with two of the Sports Illustrated that featured Ralph Sampson as an undergraduate athlete at the University of Virginia. (Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Sports Illustrated article, “His Future is Up in the Air,” by Larry Keith. December 17, 1979. (GV885 .43 .V57 K45 1979. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Excerpt of Robbie Kemp’s “Sampson’s Lasting Legacy”:

Sports Illustrated featured Ralph Sampson in a variety of articles starting with his first season at the University of Virginia in 1979. The analysis of my sources results from a combination of two specific articles: “His Future Is Up in the Air” by Larry Keith and “Hello, America, We Came Back” by Curry Kirkpatrick. Together, these articles explain both the stellar athletic talents Sampson possessed along with the passion to excel academically. Sports Illustrated reaches a national audience and is considered the premier weekly sports magazine in the country. When Larry Keith first published his article in 1979, he was revealing Sampson to an audience that had likely never heard of his accolades in an era before information was spread easily and widely. By the time Kirkpatrick published his article profiling Sampson’s return to U.Va., it is safe to assume that even the casual basketball fan had been introduced to Sampson. However, it is important to note that Kirkpatrick’s article does not emphasize the importance of Sampson’s decision as setting a precedent for extremely talented college athletes; perhaps it is with the benefit of hindsight that the lack of this emphasis is glaringly missing. Ralph Sampson could have easily turned to the NBA after his second season at the University, a move that would have earned him a six-figure salary. Although earlier quotes alluded to the criticism Sampson received, some NBA general managers approved of the move at the time as Bob Ferry of the Bullets stated, “All kids benefit from four years in college…maybe not basketballwise, but lifewise. They all benefit” (Kirkpatrick 37). Ferry’s opinion is mirrored today by the NBA’s decision to enforce a mandatory one-year waiting period after high school before being draft-eligible, although basketball at the collegiate level is not required.

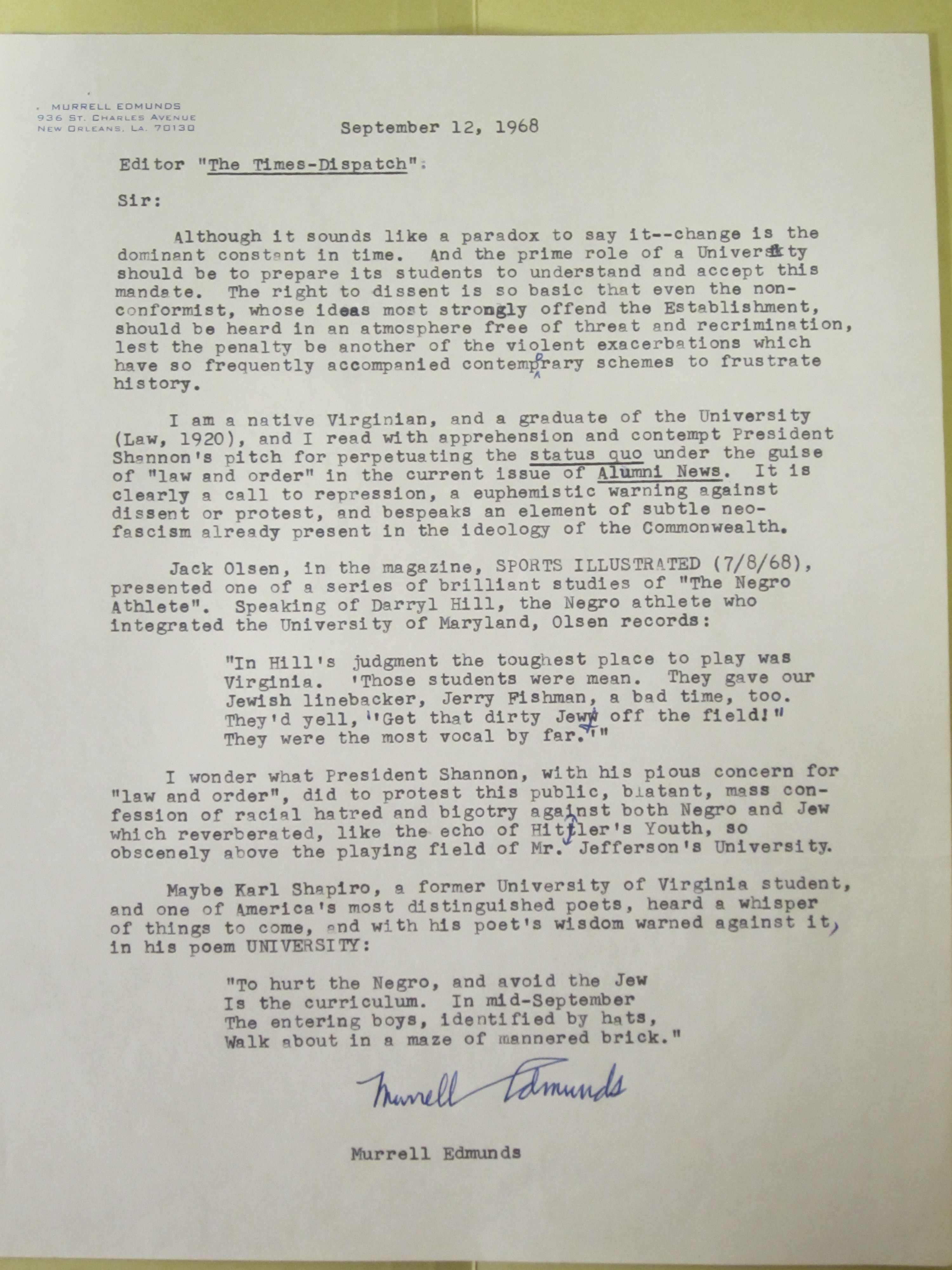

Patrick Schuler’s Untitled Essay Analyzing Murrell Edmunds’ Letter

Fourth-Year student Patrick Schuler selected a letter from the Papers of Murrell Edmunds for his assignment. Murrell Edmunds was a poet, novelist, and U.Va. alum, who wrote and spoke out against segregation and the mistreatment of African Americans during the Jim Crow era. The 1968 letter is from Edmunds to the Editor of the Richmond Times-Dispatch. In it, he uses examples of incidents in football to admonish University administration for its lack of action against mistreatment of black and Jewish students.

Patrick Schuler, Fourth-Year student, pictured with two letters written by alum Murrell Edmunds BA 1917, Law 1920, regarding the treatment of black athletes at the University of Virginia during the 1960s. Hook em! (Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Letter from Murrell Edmunds, U.Va. Class of 1917, to Virginius Dabney, Editor of the Richmond Times-Dispatch, September 12, 1968. (MSS 5989-x. Published Permission of the Estate of Murrell Edmunds. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Excerpt from Patrick Schuler’s essay:

While the University administration allowed this behavior to continue, the student body was active in promoting racial equality in other areas on life on Grounds. The “University finally actively embraced the ideals of a changing world”, calling for equality throughout the state (100 Years on the Lawn). A flier from February 17, 1969 from the University community calls the Governor and Board of Visitors to address “the affront to the black community posed by the presence on the Board of Visitors of representatives of the segregationist Massive Resistance Movement” and the lack of involvement in improving the lives of African American members of the Charlottesville community (Fliers Concerning Racism at the University of Virginia). The Student Council also declared segregated businesses off-limits to university student organizations. However, as Edmunds argues, the one thing absent from any of the University’s efforts to rid the institution of racism was the treatment of black football players. Racism survived at UVA for quite some time after Harrison Davis, Kent Merritt, Stanley Land, and John Rainey took the field for the first time. The University’s inaction on the football team contradicted their apparent commitment to ridding the community of racism on other fronts, reinforcing the perception that football was a way to maintain the Southern institution of racism.

When we look at the race of today’s best college football players or the roster of the team here at UVA, it is hard to imagine that this was the reality of college football 40 years ago. Murrell Edmund’s letter is a perfect depiction of how football was used as a vehicle to maintain the prejudiced treatment of blacks in the South during the decade following the end of legal segregation. Discrimination against black players did not end when they were allowed to play for Southern universities. While formalized acts of racism were no longer tolerated, college football provided a venue to re-assert the self-perceived superiority of white southerners, as black players were harassed on and off the field. The University of Virginia and other institutions in the South turned a blind eye to their football stadiums to maintain “tradition.”

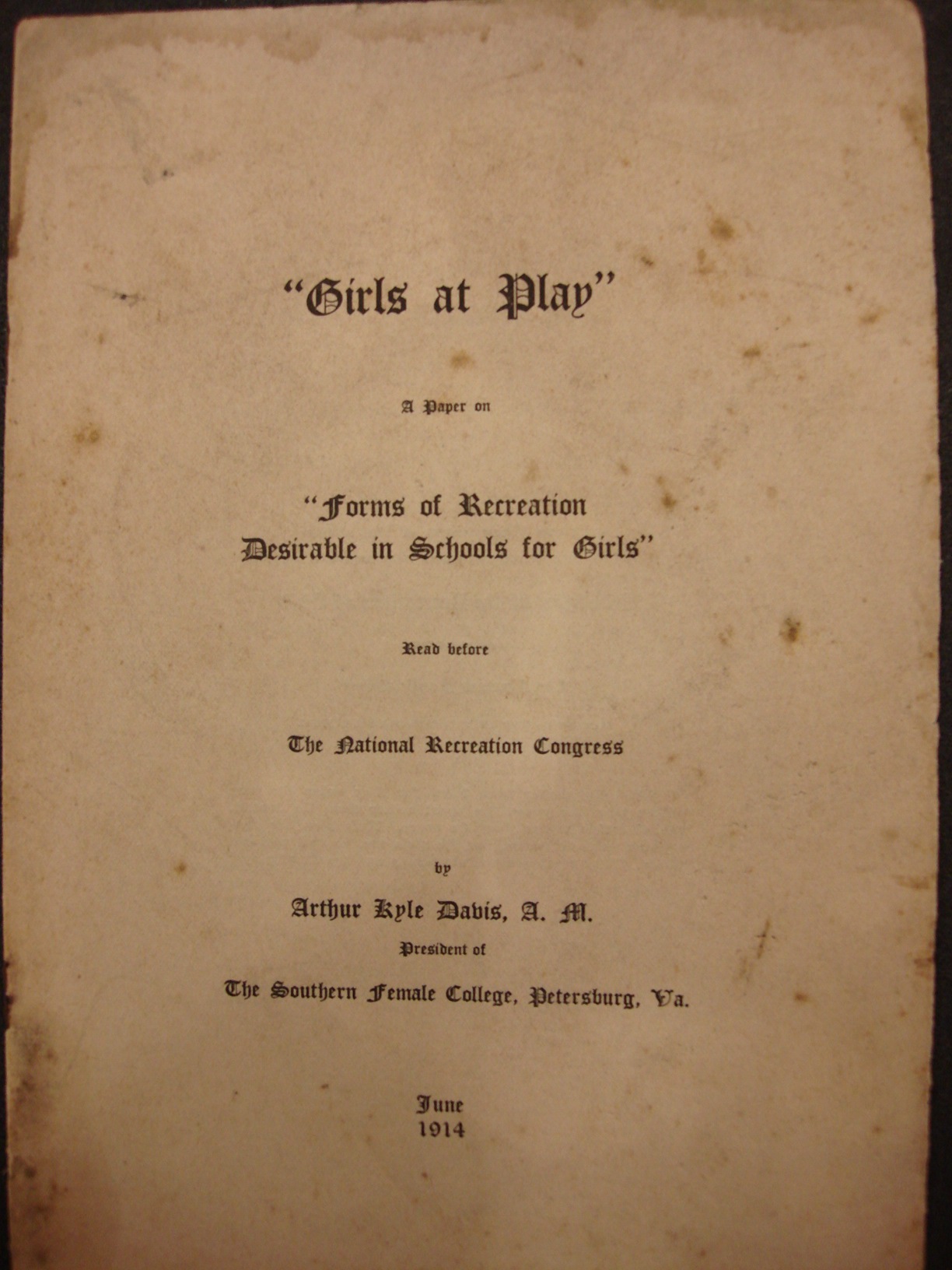

Charlotte Clarke’s” Fighting the Feminine Ideal: Social Constructs of Gender and Their Impact on How We Perceive Women in Sport”

Third-Year student Charlotte Clarke chose and analyzed the 1914 published paper, “Girls at Play” by Arthur Kyle Davis. In her paper, she explores what Davis deemed acceptable behavior and qualities for women participating in sports during the 1910s.

Charlotte Clarke, Third-Year student, photographed with “Girls at Play,” the centerpiece of her essay. (Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

“Girls at Play: A Paper on ‘Forms of Recreation Desirable in Schools for Girls'” by Arthur Kyle Davis, 1914. (LB3608 .D3 1914. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Excerpt from Charlotte Clarke’s “Fighting the Feminine Ideal”:

How female athletes are perceived by society is a topic that has been hotly contested and analyzed in recent years. Through the analysis of the paper “Girls at Play”, which was read before the National Recreation Congress in June of 1914 by Arthur Kyle Davis, A.M., his beliefs and recommendations as to the appropriate and desirable forms of recreation for girls in the early 1900’s are outlined. This paper compares the opinions expressed by Davis in 1914 to the beliefs held in today’s society in regards to women’s participation and success in sport. Through these analyses and comparisons, it will be shown that despite massive gains in equality achieved by women in many areas of society, including sport, there still persists today a perception that sport is a male dominated arena. This paper also explores how and why these beliefs are capable of infiltrating into society, and able to become established and accepted as societal norms.

Arthur Kyle Davis was the president of the Southern Female College in Petersburg VA. His father William Thomas Davis founded the college in 1863 and it ran until 1938. Davis presented his paper during an era that was socially extremely different to that of today. Women were subject to discrimination in all areas of their lives and at the time of his reading, women in America did not have the right to vote. At this time, men’s colleges did not accept female students and so between the 1860s and the 1930s, women’s colleges were founded to provide their students with the means to achieve an education that would assist them in their “female duties” as mothers and teachers. In order to demonstrate their respectability, women’s colleges placed many social restrictions on their students, and southern colleges, such as the Southern Female College, were exclusively white until the civil rights era. Society was typically male dominated and women were considered and expected to be more reserved, placid and peaceful in nature.

Kayleigh Hentges’s “Pinpointing Prejudice”

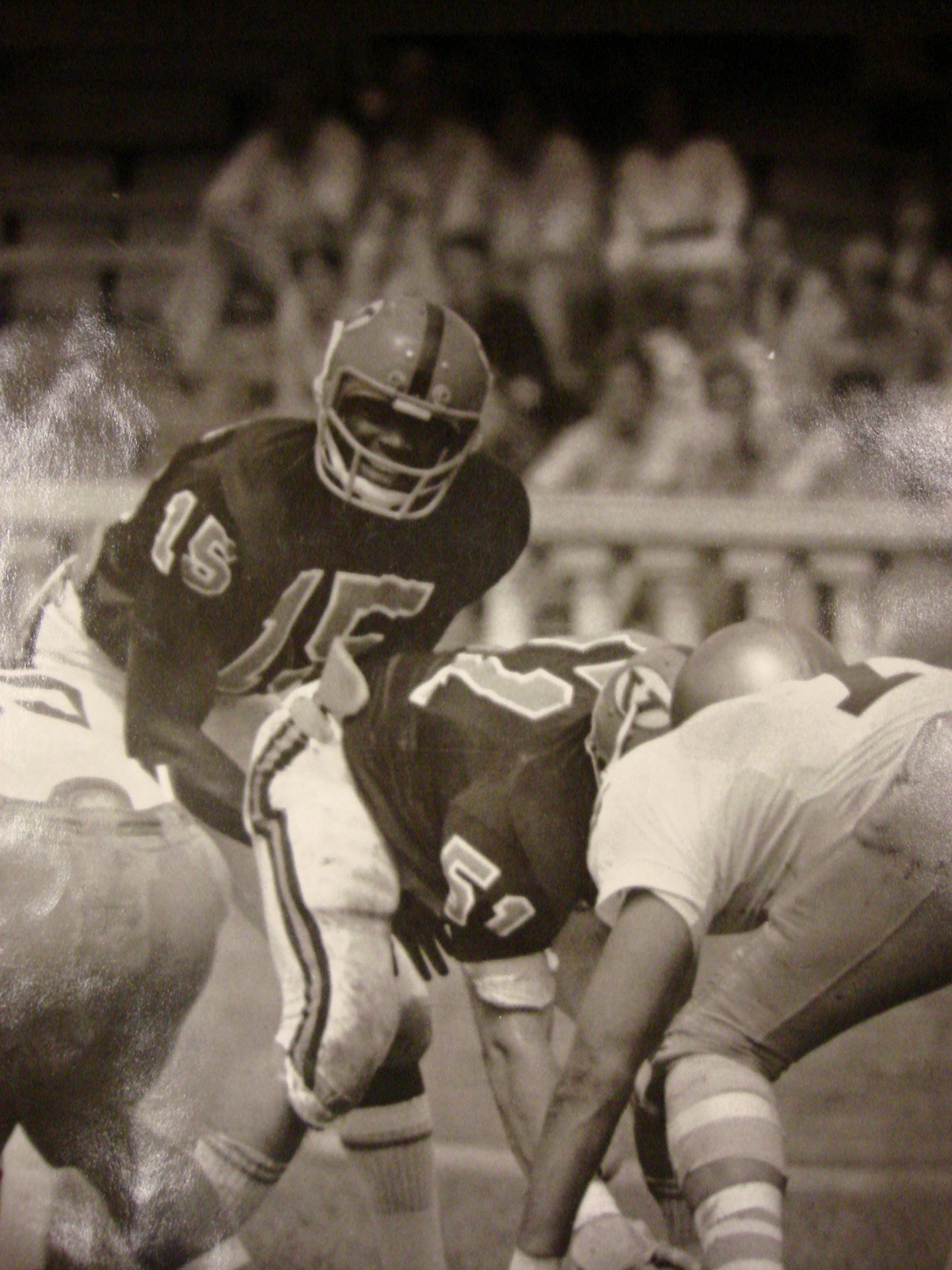

Fourth-Year student Kayleigh Hentges focused her assignment on a 1971 photograph of U.Va. quarterback Harrison Davis, which served as a starting point for discussing the difficulties and major opposition African American football players faced from fellow students and teammates when they integrated the U.Va. football team in 1970.

Fourth-Year Student Kayleigh Hentges pictured with photograph of Harrison Davis, U.Va. quarterback during the 1971 season. (Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

#15 Harrison Davis, U.Va. quarterback, from the Corks and Curls Photograph Archives. 1971 Football Season. (RG-23/48/1.841. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Excerpt from Kayleigh Hentges’s “Pinpointing Prejudices”:

As Harrison Davis took the field in 1971 in the position of starting quarterback for the University of Virginia, his reception was less than enthusiastic, and he realized his college football years wouldn’t be the idealistic football experience that most college football starters envision. The quarterback he replaced was none other than George Allen, a future politician who had transferred from University of California at Los Angeles (Phillips). The unenthusiastic reception, from both fans and students of Davis, along with three other signees- Stanley Land, Kent Merritt and John Rainey, stemmed not from a lack of talent but from their skin color. These four players were the first African Americans to be integrated into the football program at the University of Virginia (“All the Hoos in Hooville..”). Fans and students used even the smallest of mistakes that Davis made on the field as a scapegoat for their dissatisfaction with integration and the replacement of white players. Even his own white teammates would throw the “n-word” out around the four new additions to the team (Scherer). The racism that Davis experienced stands out amongst the others, however, because he was chastised not only for being black but also for his position as a black quarterback. Although the situation has improved today, white quarterbacks still largely outweigh the number of black quarterbacks, with only 6 black quarterbacks in the starting position as of 2011 (Gray). I charge that without the inconclusive scientific studies on the African American body in relation to athletic ability beginning in the 1930’s, the assumptions that “White quarterbacks are smart but not athletic, Black quarterbacks are athletic but not smart” would not have prevailed and a more equal representation between the two races at the quarterback position could exist (Buffington).

Conclusion

We don’t usually get to see the finished product of the work done here by students. We watch them learn to find, request, and handle materials, and then they disappear. Thank you to Dr. Allison Wright, her Sports, Media, and Society class, and especially Chris Wood, EP Stonehill, Robbie Kemp, Patrick Schuler, Charlotte Clarke, and Kayleigh Hentges for sharing with us these wonderful results!