This week, we feature a guest post from Special Collections staff member George Riser:

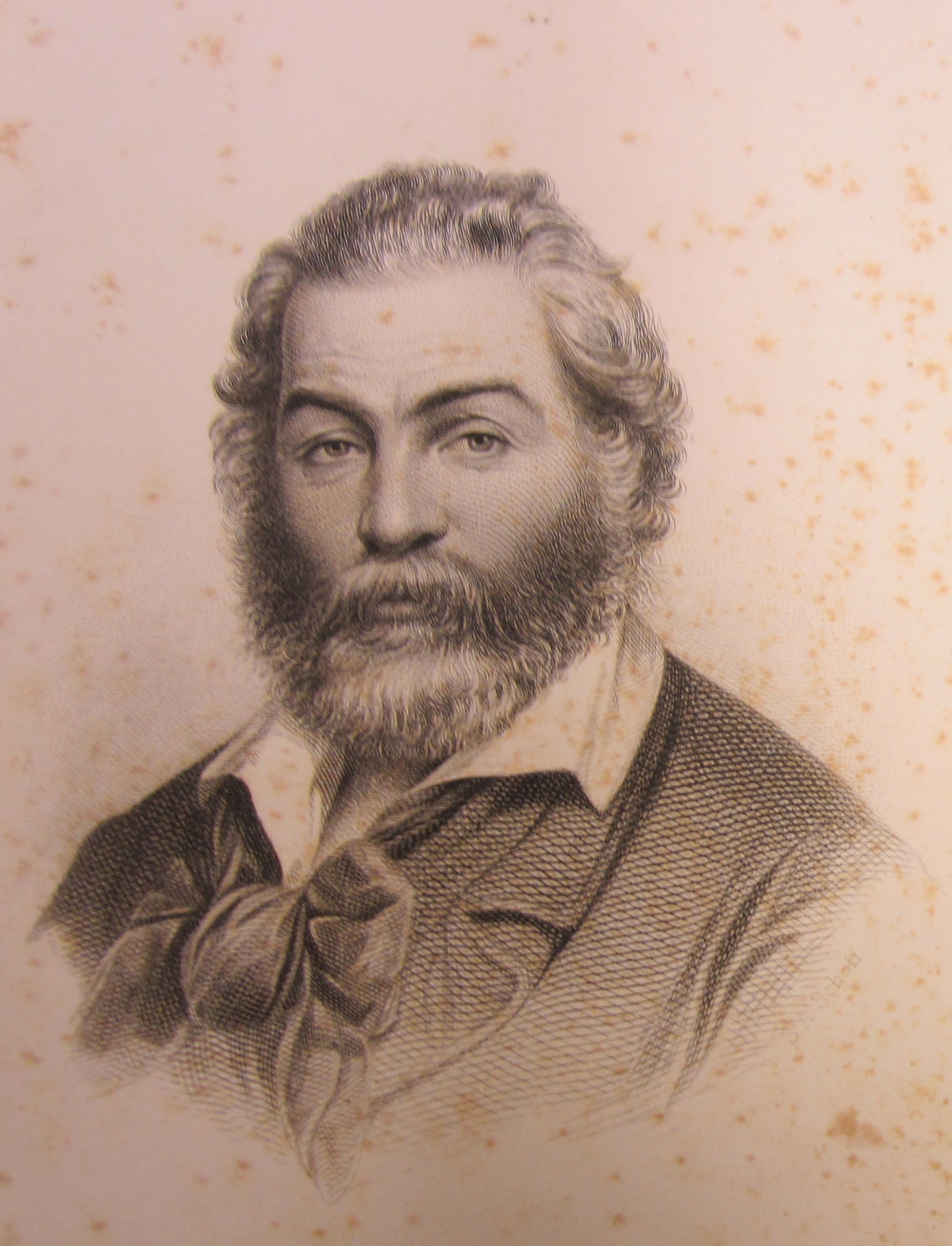

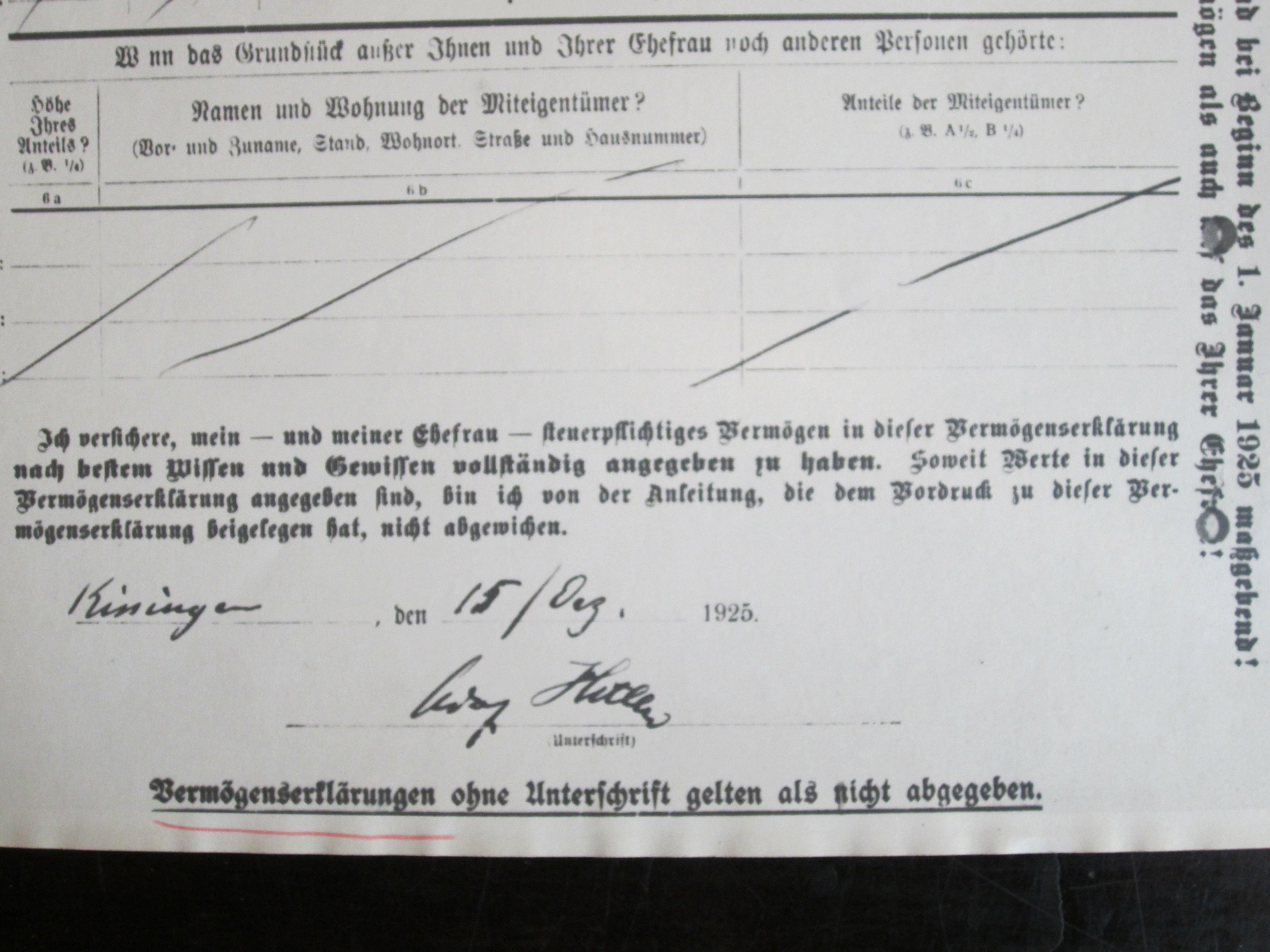

When Walt Whitman released his ‘idiomatic book of my land’ in 1855, he was thirty-six years old. Leaves of Grass, then twelve untitled poems in free style verse, was fully the work of an author who financed the printing, assisted in the typesetting, designed the extravagant cover, and acted as publisher and salesman. Though praised by Ralph Waldo Emerson in a private letter–“I greet you at the beginning of a great career”–the poems initially bewildered or shocked most early readers, not only in their lack of conventional rhyme and meter, but also in their use “of language and subject matter so coarse and crude as to be not fit for a mixed audience” (Charles Eliot Norton, Putnam’s Monthly: A Magazine of Literature, Science, and Arts, 6 September 1855). Not all of the critics were so kind. Rufus Griswold in his review in Criterion in November 1855 wrote, “as to the volume itself…it is impossible to imagine how any man’s fancy could have conceived such a mass of stupid filth unless he were possessed of the soul of a sentimental donkey that had died of disappointed love” (Oddly, one of our Library’s copies of the first printings is a presentation to Rufus Griswold). Charles A. Dana, writing in the July issue of The New York Daily Tribune, notes “the poems certainly original in their external form, have been shaped on no pre-existent model out of the author’s own brain. Indeed, his independence often becomes coarse and defiant. His language is too frequently reckless and indecent.”

Can a work of art as original as Leaves of Grass spring out of “no pre-existent model,” simply from “the author’s own brain?” Our library holds twenty-five items that pre-date the first printing of Leaves of Grass in 1855. A look at this publication history can give, in many cases, insight into the genesis of the wild, innovative poems that formed the then revolutionary book of poems.

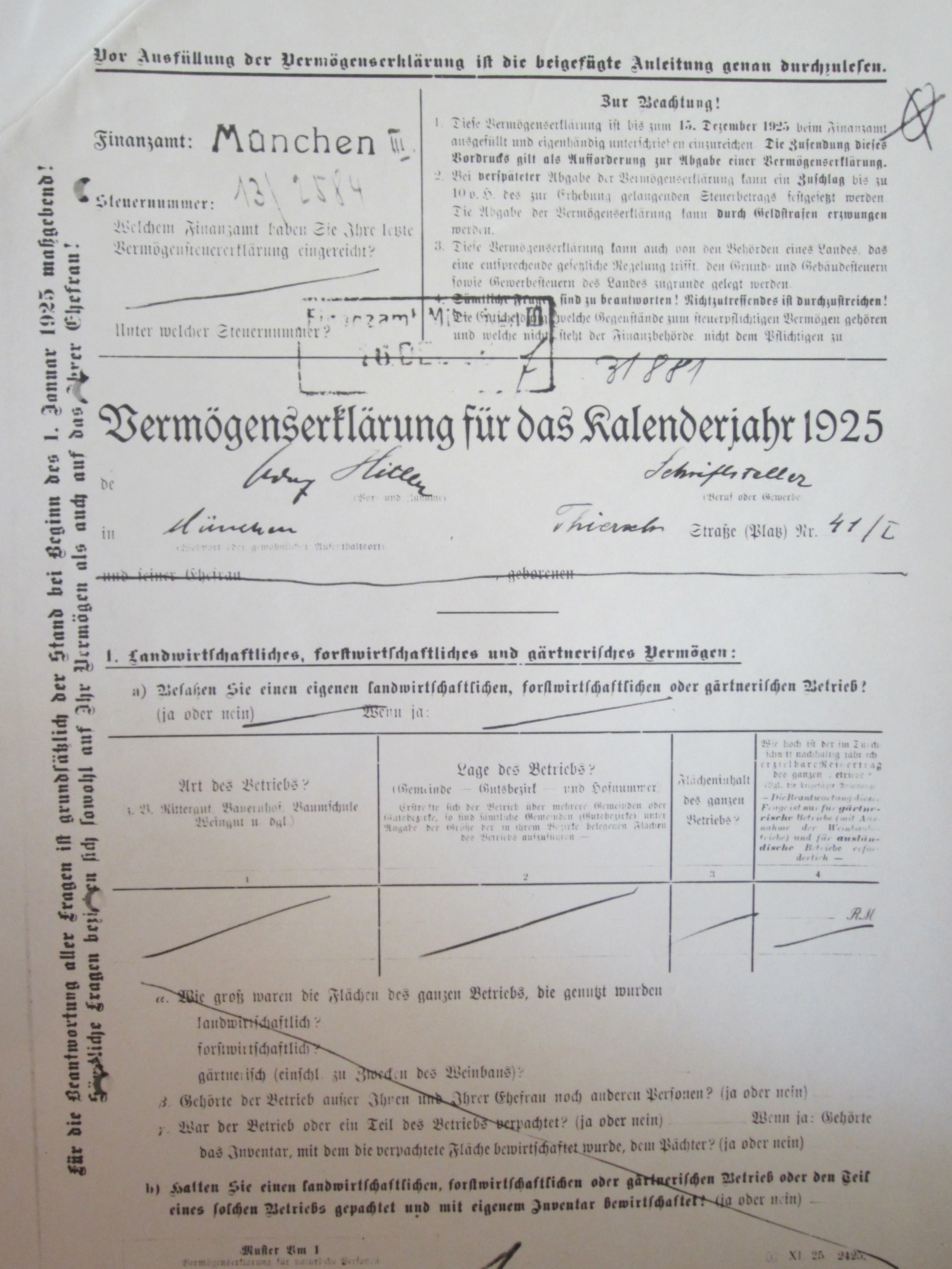

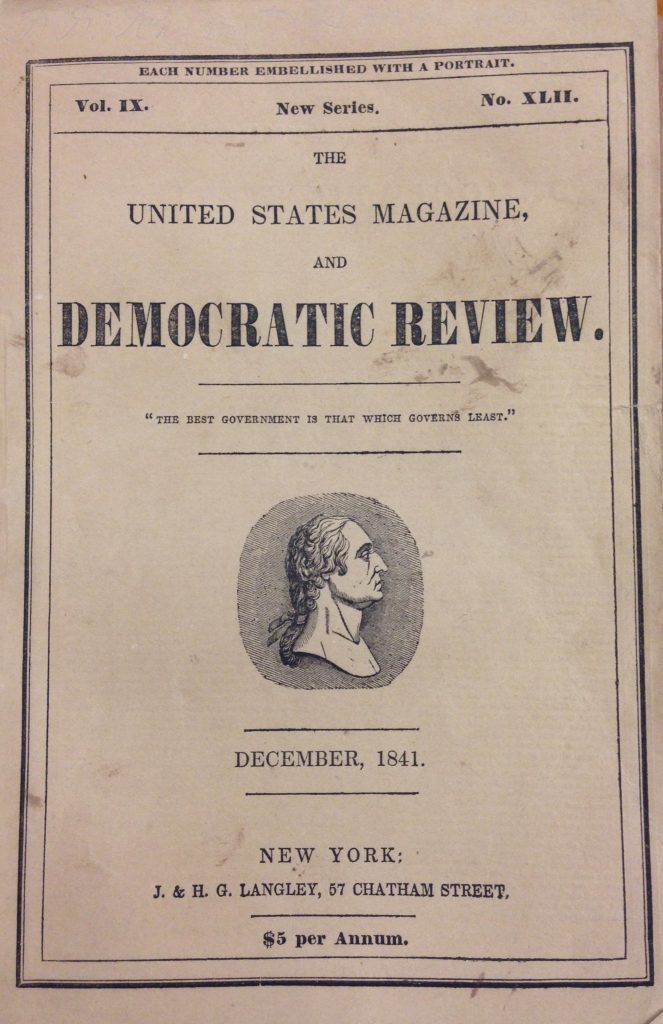

Whitman’s first published piece, “Death in the School-Room” appeared in The Democratic Review in August 1841. Written when Whitman was 21, the story drew on his experience as an itinerant teacher and was an indictment of what he called “the old-fashioned school-masters with their reliance on discipline and corporal punishment.”

Front cover of The United States Magazine and Democratic Review, (December 1841), which featured Whitman’s story “Bervance: or, Father and Son.” (PS3222 .B47 1841, Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature. Photo by Molly Schwartzburg.)

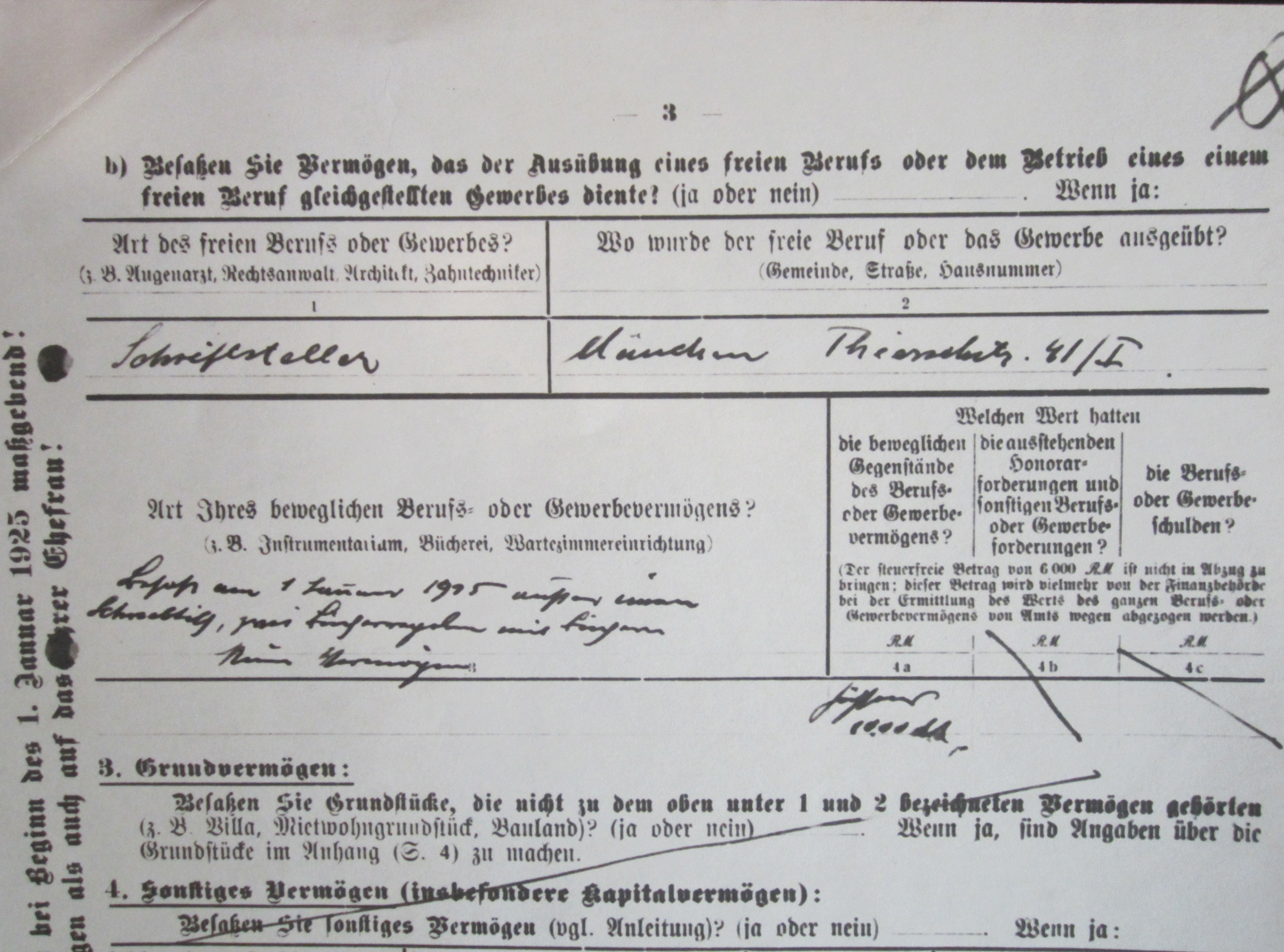

An early poem, “Death of the Nature-Lover,” appearing in Brother Jonathan in March 1843, and attributed to Walter Whitman, uses a strict meter and rhyme, though it employs Whitmanesque themes:

Not in a gorgeous hall of pride

Where tears fall thick, and loved ones sigh,

Wished he, when the dark hour approached

To drop his veil of flesh and die.

The title page from Brother Jonathan, (New York, N.Y.: March 11, 1843) featuring Whitman’s poem, “Death of the Nature-Lover.” (PS3222 .D45 1843, Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature. Photo by Molly Schwartzburg.)

Whitman worked for many of the serial publications that printed his early work, usually as compositor, pressman, or editor, including a stint with John Neal, publisher of Brother Jonathan. Neal, a popular novelist of the time, wrote in his 1823 novel, Randolph, “I do, in my heart, believe we shall live to see poetry done away with–the poetry of form I mean–of rhyme, measure, and cadence.…poetry will disencumber itself of rhyme and measure and talk in prose–with a sort of rhythm, I admit,” lines that Whitman seemingly took to heart.

Whitman’s “Death of the Nature-Lover” as it appeared in Brother Jonathan, above. (Photo by Molly Schwartzburg.)

Ralph Waldo Emerson contributed to many of the same publications as Whitman, and called upon American writers to “strike an original relation with the universe.’”Whitman took heed, writing, ‘”I was simmering, simmering, simmering; Emerson brought me to a boil.”

Whitman also worked for and contributed to The Broadway Journal at the time it was owned and edited by Edgar Allan Poe. The 29 November 1845 issue features a piece by Whitman, “Art-singing and Heart-singing,” that gives credit to a popular, though low, American singing style. In the November 20 issue of the same year, Poe responding to criticisms of a recent poetry reading, takes issue with a number of critics (to one: “we advise her to get drunk, too, and as soon as possible—for when sober she is a disgrace to her sex—on account of being so awfully stupid”), and ends with “a note to correspondents – ‘Many thanks to W.W.’” Whitman may have learned a lesson in withstanding critical condemnation from Poe, who spent his editorial career inviting invective.

The opening lines of Whitman’s essay, “Art-Singing and Heart-Singing,” printed in The Broadway Journal, (November 29, 1845). This issue was edited by Edgar Allen Poe. (PS3222 .A7 1845, Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature. Photo by Molly Schwartzburg.)

Poe thanks correspondents for their assistance in his “Editorial Miscellany,’ for The Broadway Journal issue, (November 22, 1845), including ‘W.W.,’ purportedly Walt Whitman. (PS3222 .A7 1845, Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature. Photo by Molly Schwartzburg.)

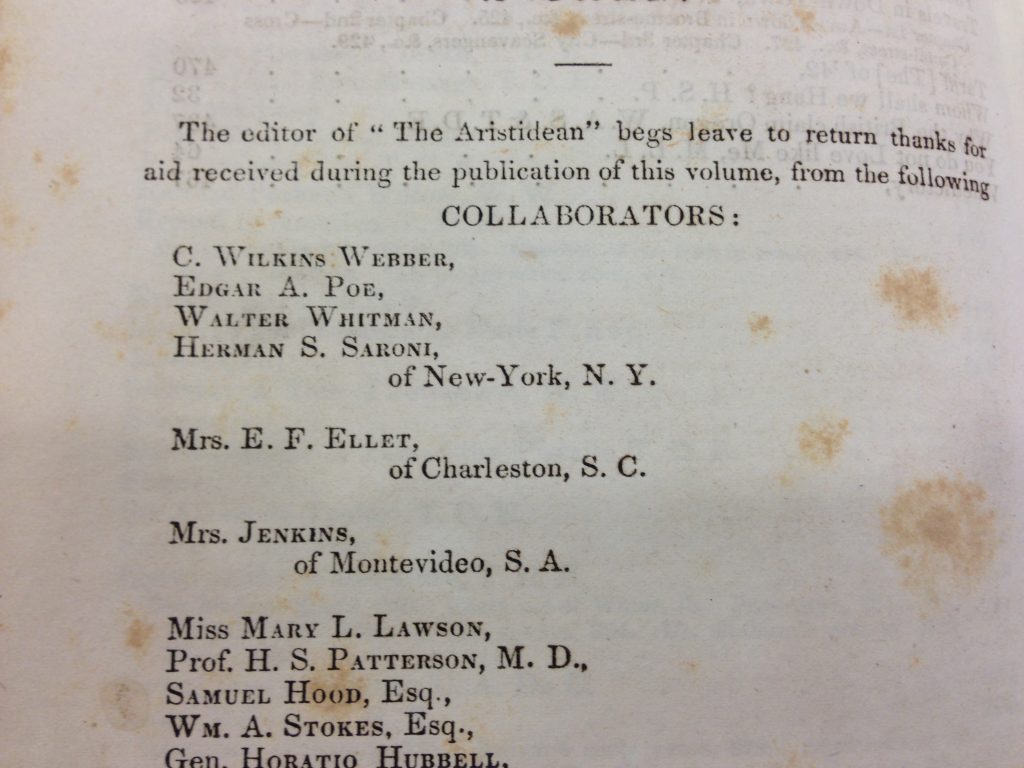

Poe and Whitman were linked more than once in professional publications. In this image, we see editor Thomas Dunn English thank collaborators, including Edgar A. Poe and Walter Whitman, in the opening pages of the March 1845 issue of The Aristidean. (A 1846 .A75, Tracy W. McGregor Library of American History. Photo by Molly Schwartzburg.)

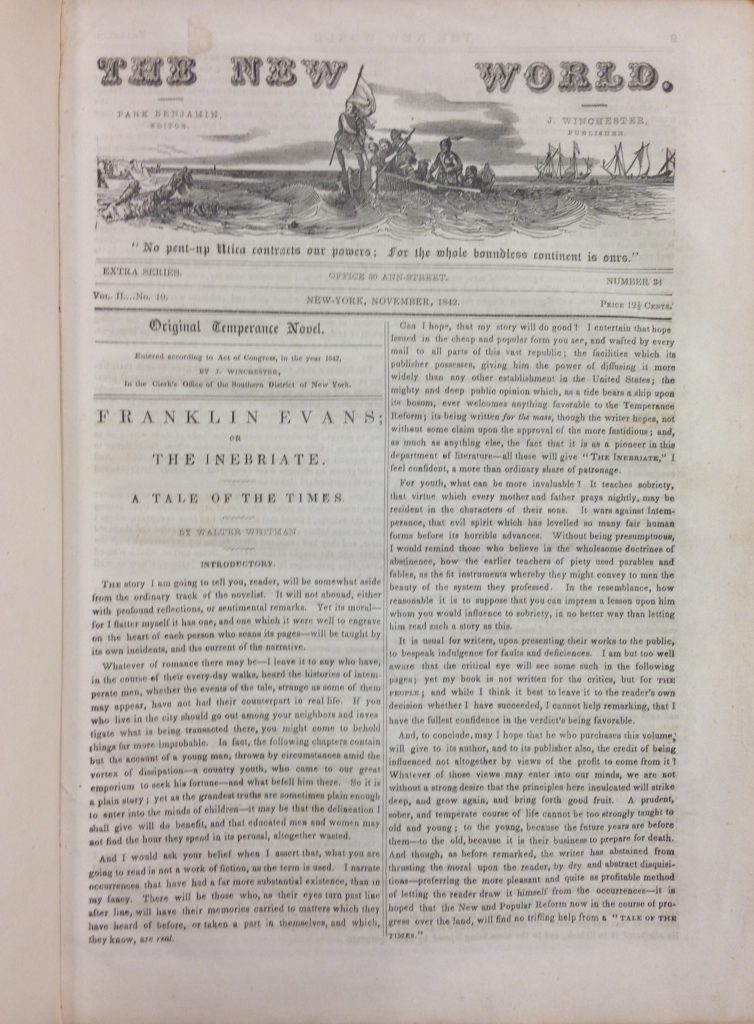

In 1942, Whitman published his only full length novel, Franklin Evans or The Inebriate: A Tale of the Times in Park Benjamin’s paper, The New World. Franklin Evans was a novel of temperance that was an embarrassment to Whitman in his old age, but reflected an early concern for alcoholism, which may have affected his father and his brother-in-law. It is also a theme that appears in later editions of Leaves of Grass, though lacking the sensationalist style popular at that time.

The front cover of The New World (New York, N.Y.: 1842) featuring the first printing of Walt Whitman’s Franklin Evans; or, The Inebriate. A Tale of the Times. (PS3222 .F7 1842, Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature. Photo by Molly Schwartzburg.)

These are but a few examples of Whitman’s early writings that can give insight into the origins of the remarkable book of poems, Leaves of Grass.

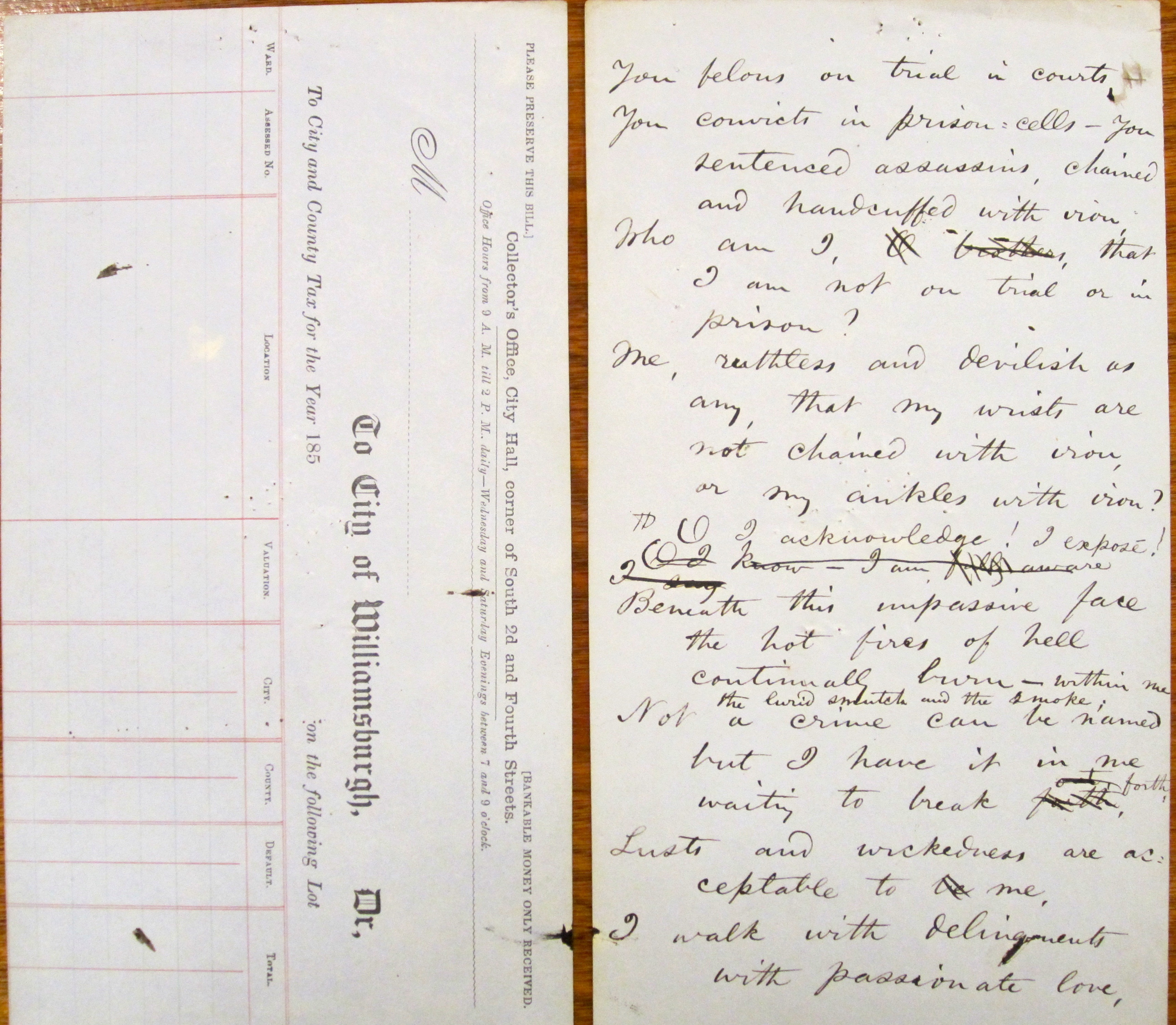

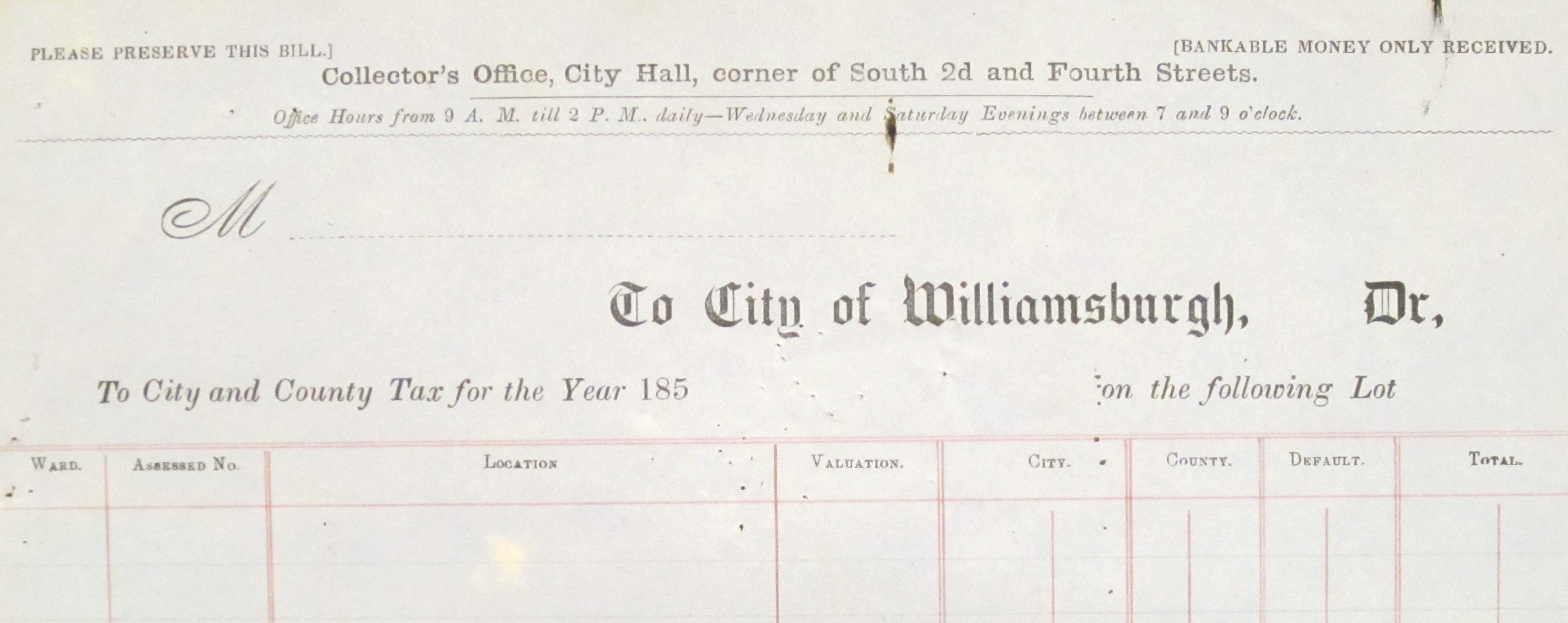

In closing, we include a passage from that volume’s first edition, and one last contemporary commentary:

Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos, disorderly, fleshly, and sensual, no sentimentalist, no stander above men or women or apart from them, no more modest than immodest…

–Leaves of Grass

Walt Whitman is a printer by trade, whose punctuation is as loose as his morality, and who no more minds his ems than his p’s and q’s.

–Anonymous from The Washington Daily National Intelligencer, (18 February 1856)