Right now U.Va.’s iconic Rotunda—the centerpiece of Thomas Jefferson’s “Academical Village” and the U.Va. Library’s original home—is undergoing a multi-year, $50 million restoration. These have been interesting times for sidewalk supervisors and armchair architects as the restoration work reveals hitherto unknown details about the Rotunda’s design and construction. It has also been an interesting time Under Grounds, for we have fortuitously acquired two early images of the Rotunda previously lacking from our collection. Although these images do not advance our understanding of the Rotunda’s architecture, they do enhance our knowledge of its early iconography.

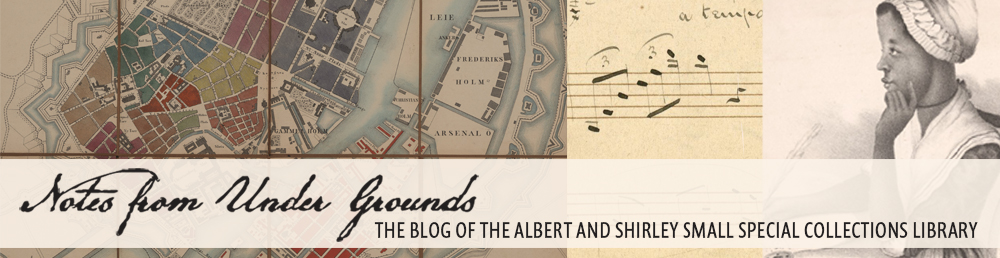

The Academical Village, as it appeared in Roux de Rochelle, Stati Uniti d’America (Venice, 1839) (E178 .R8216 1839).

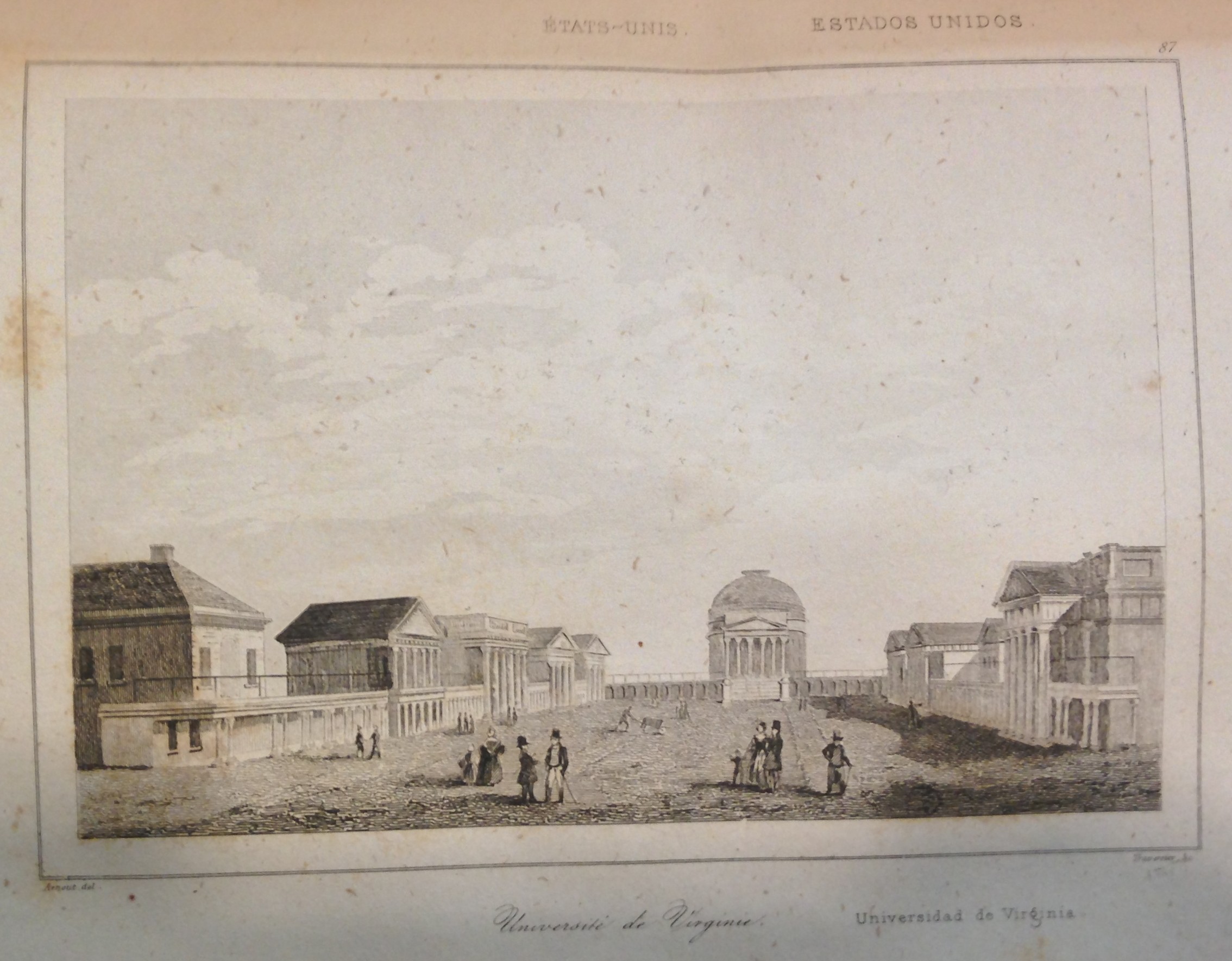

The two newly acquired images are engraved plates in the Italian (Venice, 1839) and Spanish (Barcelona, 1841) translations of Jean Baptiste Gaspard Roux de Rochelle’s États-Unis d’Amérique. This history and description of the United States, first issued in 1837 as part of the series, L’univers, histoire et description de tous les peuples, proved popular and was reprinted several times. Perhaps its major selling point was the 96 engraved plates depicting historical personages and events, as well as numerous contemporary American views. Plate 87 is of special interest, as it depicts U.Va.’s Academical Village as it looked in the mid-1820s, after the Rotunda, faculty pavilions, and student rooms had been completed.

U.Va. has long held copies of the Paris, 1837 and 1838 editions, and the Stuttgart, 1838 German translation. That we lacked the Italian and Spanish translations was brought to our attention this fall, when a collector offered to donate copies: “I should tell you that I’ve removed the U.Va. plates, but perhaps you could use the books anyway?” We politely declined the gift, choosing instead to purchase complete copies on the antiquarian market. To our knowledge, only the Mexico [City], 1841 Spanish edition still eludes our dragnet.

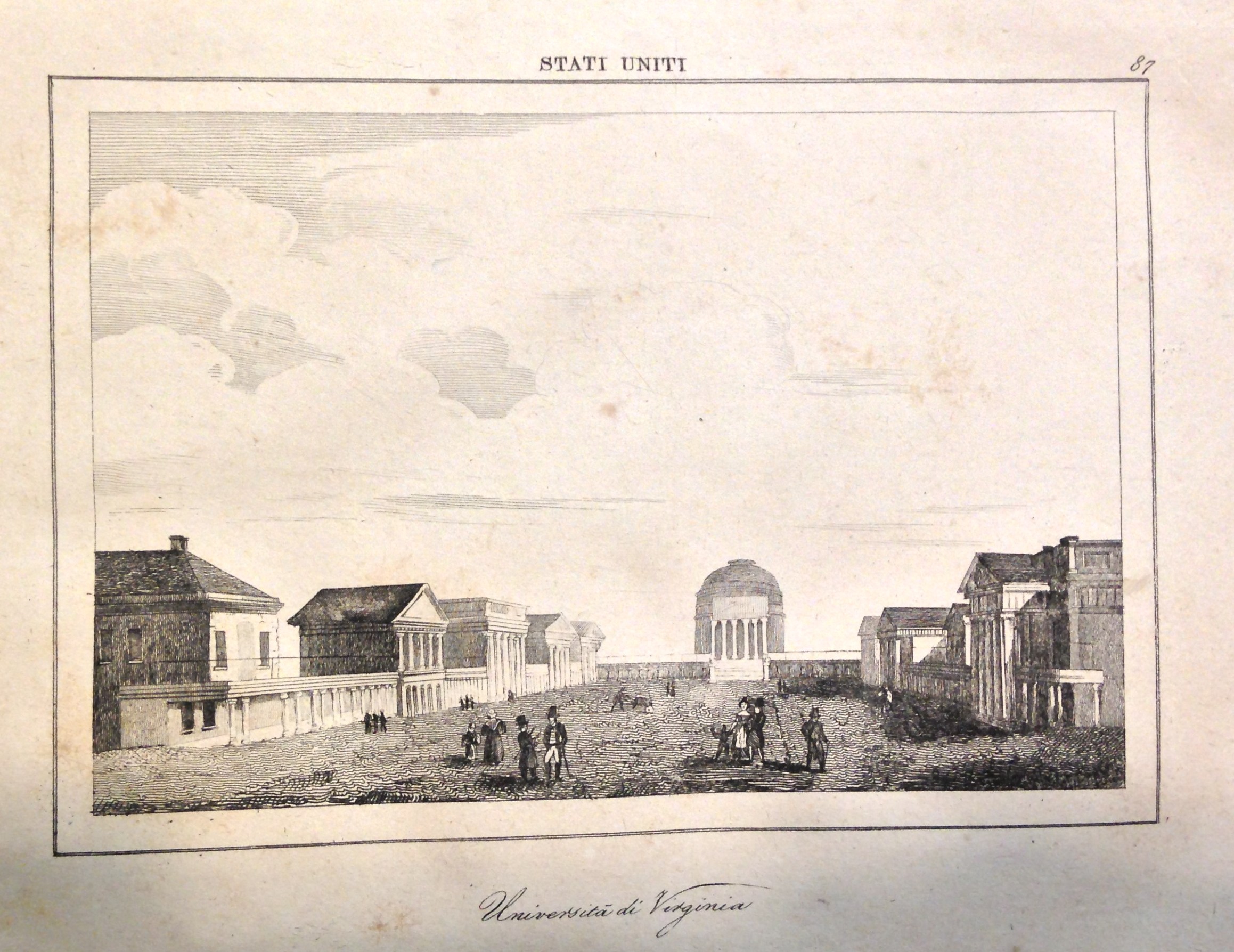

The Academical Village as it appeared in Roux de Rochelle, États-Unis de’Amérique (Paris, 1837) (E178 .R82 1837)

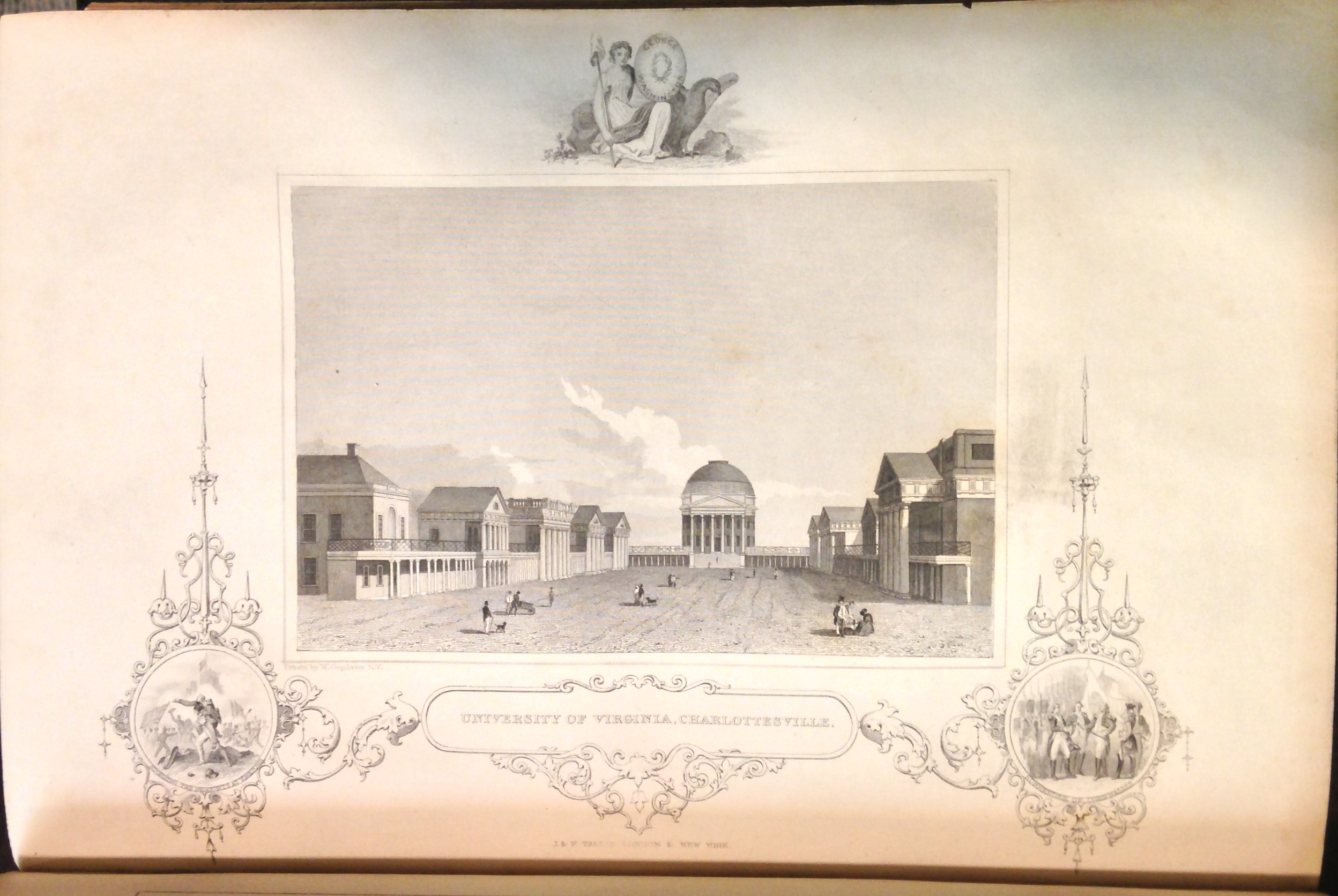

Although the text mentions U.Va. only in passing, it was through the engraving in Roux de Rochelle’s work that many Europeans first learned of U.Va. and its distinctive architecture. What few readers probably realized is that Roux de Rochelle’s knowledge of U.Va. was by no means first-hand. Born in 1762, Roux de Rochelle had served as French consul in New York during the early 1820s, returning as French Minister to the U.S. from 1830 to 1833. Perhaps it was then that he saw a copy of John Howard Hinton’s two-volume History and topography of the United States, published in London, New York, and Philadelphia from 1830-1832. Roux de Rochelle evidently decided to write a similar work for a French audience, and though the text is quite different, its many engraved plates are largely copies of those prepared for Hinton’s work. Indeed, Hinton’s plate 81 is an identical view of U.Va.’s Academical Village.

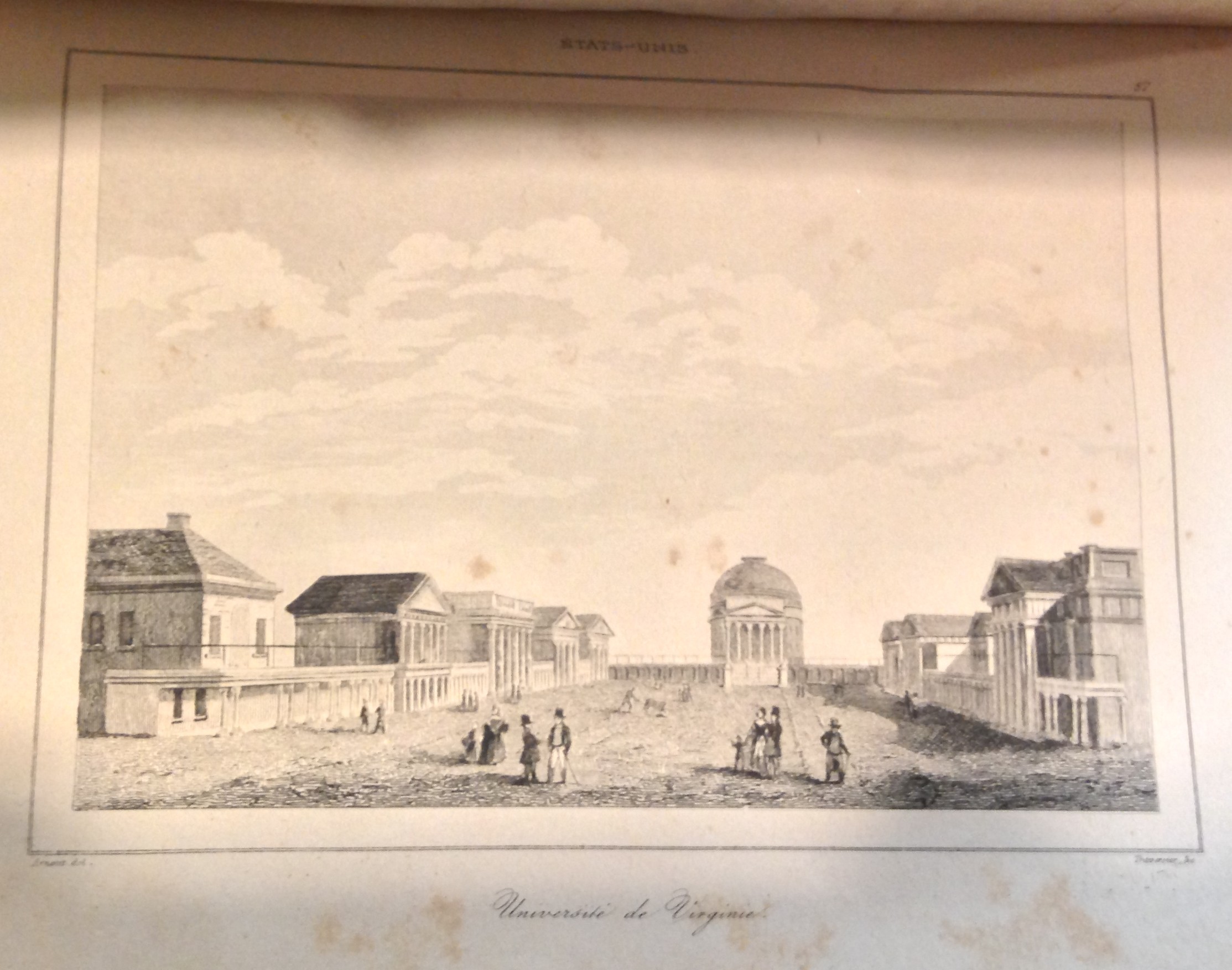

Plate 81 from John Howard Hinton, The history and topography of the United States (London & New York, 1830-1832) (E178 .H691 1830)

But even Hinton’s plate is derivative, for its immediate source was the highly detailed view of U.Va., engraved by Benjamin Tanner, that appears on the top left sheet of Herman Böÿe’s famous 1826 wall map of Virginia. For Hinton’s work, Tanner’s engraving was copied in New York by landscape artist William Goodacre, whose drawing was sent to London to be engraved on steel by artists in the employ of Fenner Sears & Co. The Hinton engraving is smaller in size and less detailed than Tanner’s view, though some effort was made to render the architectural elements relatively faithfully.

In preparing Roux de Rochelle’s work for the press, the Paris publisher commissioned 96 full-page engraved reproductions of existing artworks. Some of the sources are credited in the text, though the liberal copying of plates from Hinton’s work goes unmentioned. In the Roux de Rochelle plate—signed by “Arnoult” as designer [sic] and “Traversier” as engraver—the Hinton view is reduced still further in size and the architectural details muddied somewhat. One wonders whether the book’s European readers could derive from this view an informed appreciation of Jefferson’s architectural vision.

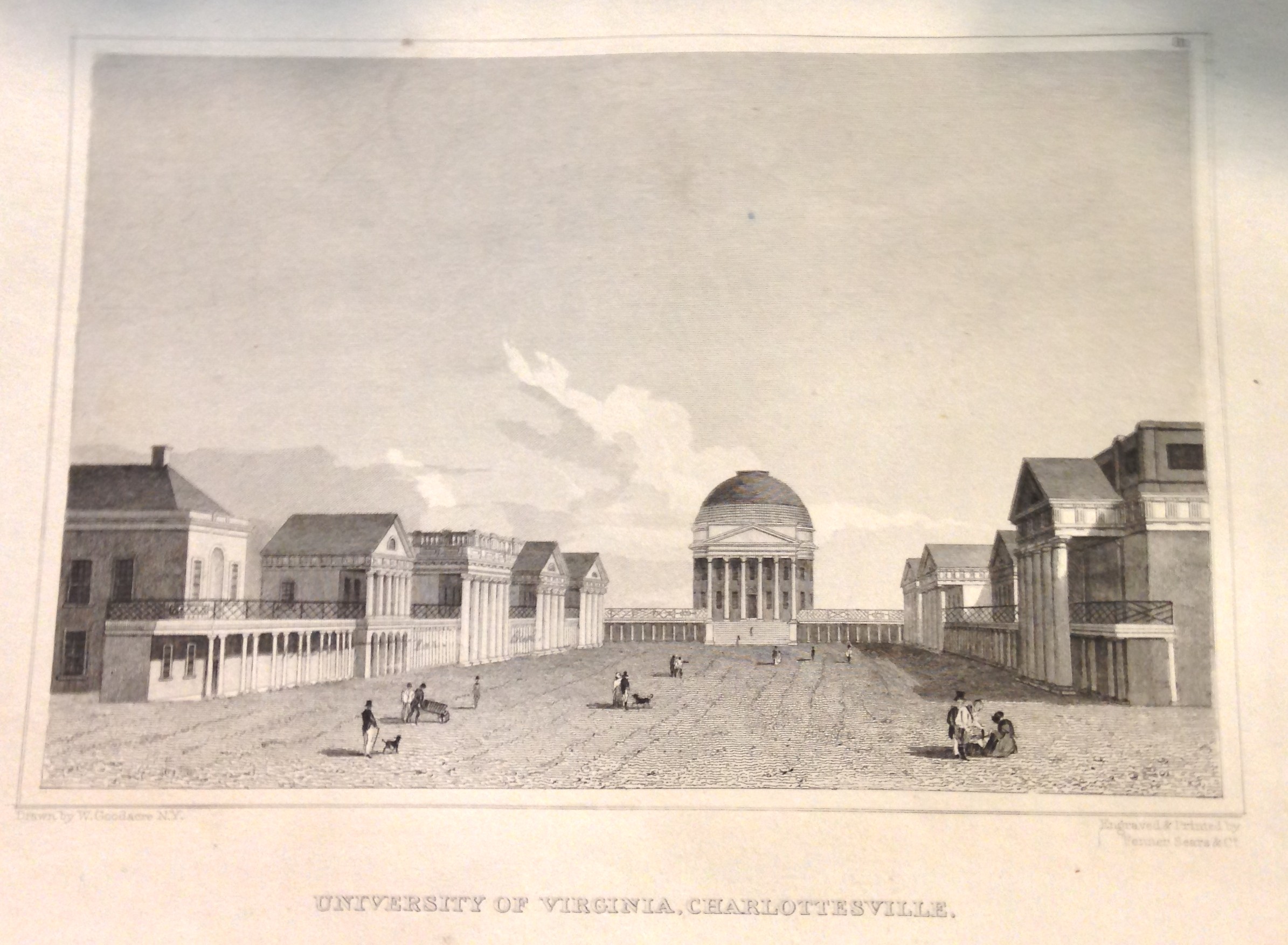

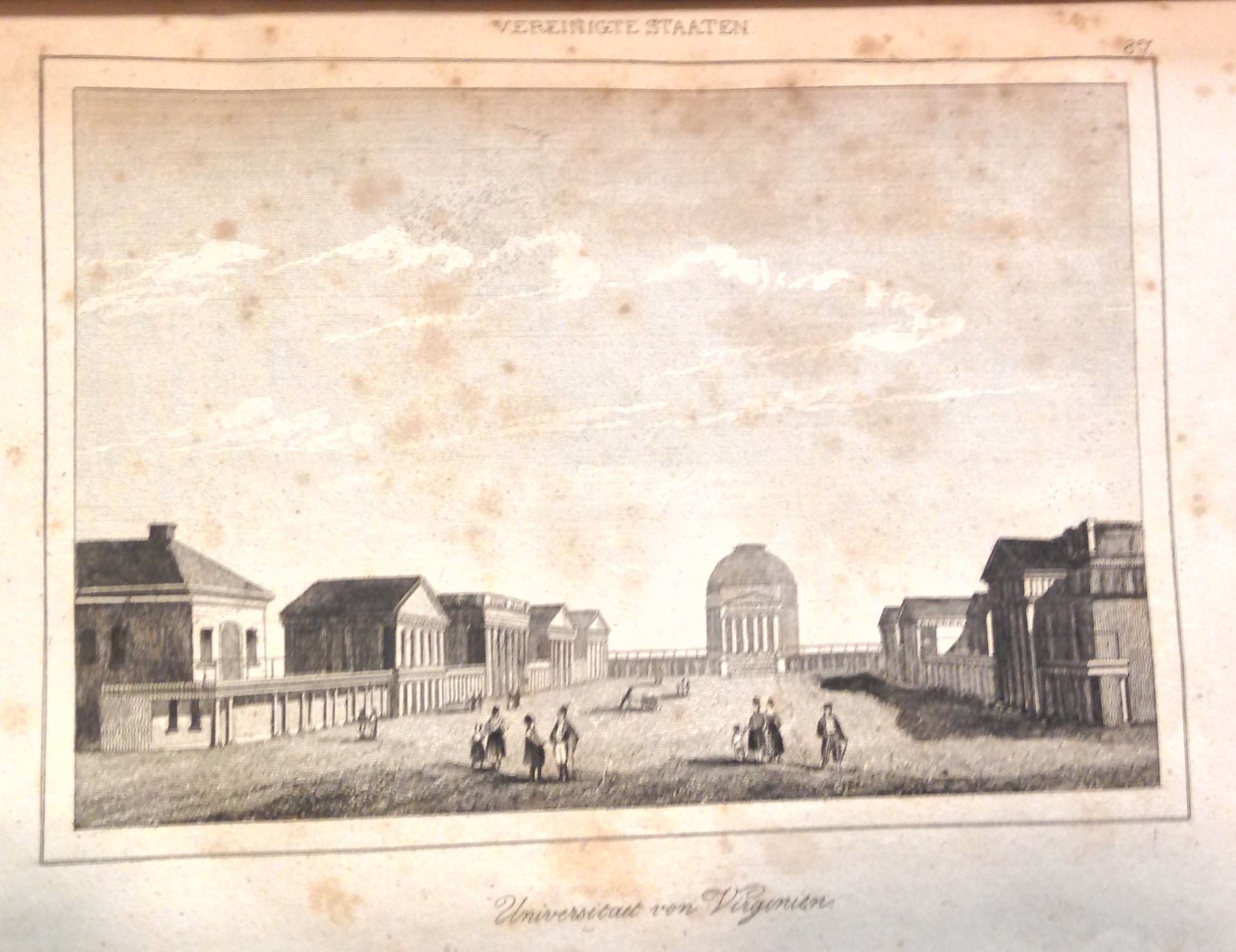

The Academical Village reinterpreted for the German translation of Roux de Rochelle: Vereinigte Staaten von Nord-Amerika (Stuttgart, 1838) (G115 .W4 1838)

A year after Roux de Rochelle’s work first appeared in Paris, a German translation was published in Stuttgart. The Stuttgart publisher did not have access to the engraved plates used for the Paris edition—indeed, per the custom of these pre-copyright days, he likely did not bother to obtain permission to translate and republish the work—so it was necessary to commission German artists to re-engrave the 96 plates. The U.Va. view is a very close copy, albeit a less careful rendering; and while the engraver dutifully reproduced the buildings, he took a bit of artistic license with the human figures on the Lawn.

The following year, the Venice publisher of the Italian translation faced an identical problem and solved it in the same way, by commissioning copies of the 96 plates. And once again, various architectural details have been lost or distorted when re-engraved, and minor liberties taken with the human figures.

The French plate reused, with added captions in Spanish, in Roux de Rochelle, Historia de los Estados-Unidos de América (Barcelona, 1841) (E178 .R8218 1841)

Not so with the Spanish translation published in Barcelona in 1841, however. Here the publisher evidently sought and obtained permission to illustrate the edition with the Paris engravings, to which an additional caption in Spanish has been added. (Presumably the Mexico City edition is a reissue of the Barcelona printing and also contains the Paris engravings, but perhaps not.)

The Hinton plate reappeared in the 4th edition of The history and topography of the United States of America (London & New York, 1850?) with an added decorative border (E178 .H691 1850)

And what, finally, of the Hinton plate? Although absent from the second edition of Hinton’s work (Boston, 1846), it reappears in the third and fourth editions (London and New York, 1849 and [1850?]), but with a new caption and an added decorative border.