We are delighted to present to you, the letter:

D is for “Detroit” Single Stroke Antique, which is one of 75 alphabets represented in Frank H. Atkinson’s Atkinson Sign Painting up to Now: A Complete Manual of Sign Painting. Chicago: Frederick J. Drake & Co., 1915 (not yet catalogued. Gift of Nicholas Curtis. Photograph by Petrina Jackson

D is for Darwin

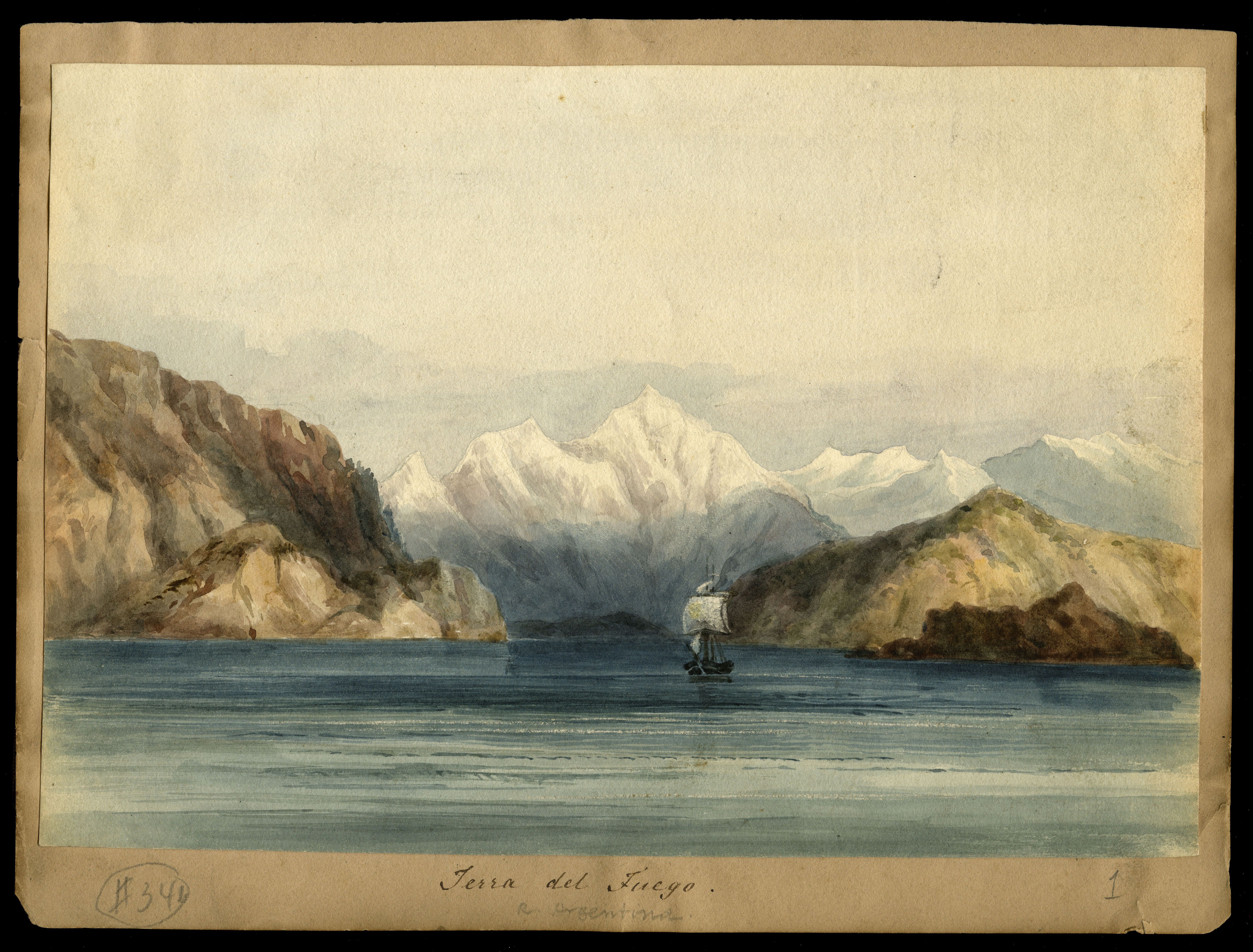

As a medical student in London, Paul Victorius began collecting rare books and manuscripts, focusing primarily on Charles Darwin and the theory of evolution. Victorius returned to the United States in 1940 and in 1949 the University of Virginia acquired his collection. The Victorius Evolution Collection consists of over 800 books and 150 manuscripts relating to Darwin’s (and his contemporaries’) discoveries. Two highlights of the collection are watercolors of the H.M.S. Beagle by Conrad Martens.

Contributed by Edward Gaynor, Head of Description and Specialist for Virginiana and University Archives

Portrait of Charles Darwin, 1860. (MSS 3314. Paul Victorius Evolution Collection. Image by U.Va. Library Digitization Services)

H.M.S. Beagle, “Terra del Fuego,” watercolor by Conrad Martens, ca.1832. (MSS 3314. Paul Victorius Evolution Collection. Image by U.Va. Library Digitization Services.)

H.M.S. Beagle, “Mount Sarmiento in Terra del Fuego,” watercolor by Conrad Martens, ca.1832. (MSS 3314. Paul Victorius Evolution Collection. Image by U.Va. Library Digitization Services.)

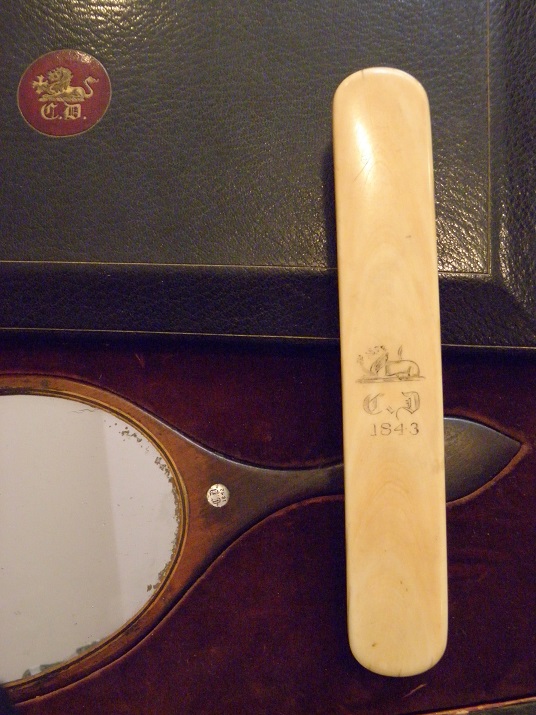

D is for Desk of Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens embarked from Liverpool aboard the RMS Britannia on January 3, 1842, landing in Boston, on a tour of approximately 17 U.S. cities, including Richmond, Virginia. What would a prolific writer of novels, poetry and plays require for such a journey? A pearl inlaid travel desk, complete with quill pen, ink well, hat brush, ivory watch stand, and wooden match-case. Sensibly, in preparation against the winter winds of the northeastern States, a glass liquor flask accompanied the writer as well. In October of the same year, his book American Notes for General Circulation was published in England.

Contributed by Donna Stapley, Assistant to the Director

Portrait of Charles Dickens, photographed by George Herbert Watkins, 1858. (Image from Wikimedia Commons.)

Charles Dickens’ desk, quill pen, album, and manuscript letter. (MSS 10562. Photograph by Donna Stapley.)

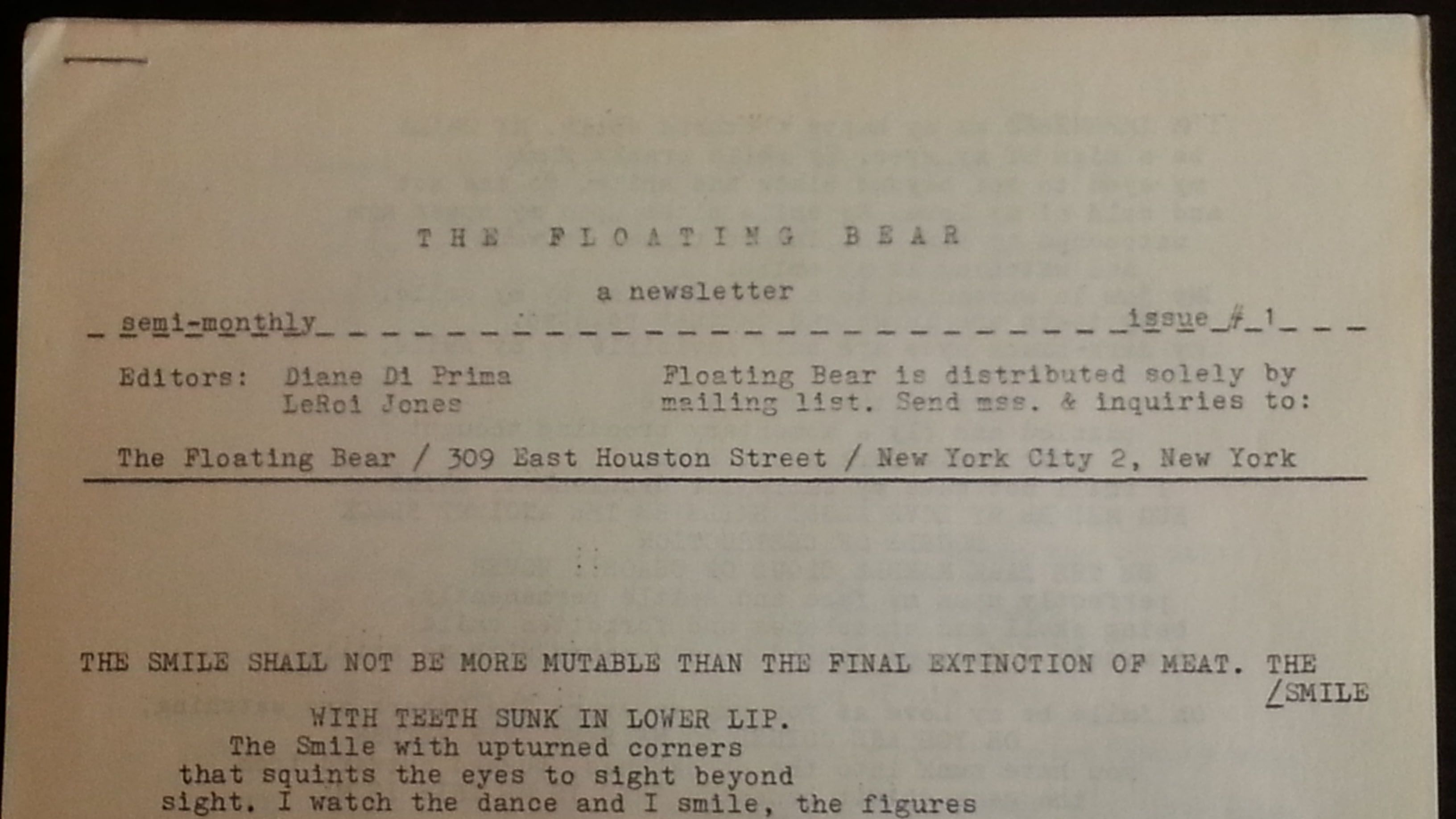

D is for Diane Di Prima

Often thought of as a poet who bridged the aesthetics of the Beats and the Hippie Movements, Diane Di Prima grew up in Brooklyn, and became a seminal figure in the early days of the Beat Movement. With Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones), she founded the influential Beat magazine, The Floating Bear, and was friends and colleagues with Allen Ginsberg, Timothy Leary, William Burroughs, and Gregory Corso, among others. A search of our Library’s catalog shows 54 records related to Diane Di Prima.

Contributed by George Riser, Collections and Instruction Assistant

Cover of Diane Di Prima’s This Kind of Bird Flies Backward, 1958. (PS3507.I68 T48 1958. Gift of Marvin Tatum. Photograph by Petrina Jackson).

Detail of the first Issue of Floating Bear, edited by Diane Di Prima and LeRoi Jones (aka Amiri Baraka). This issue includes poems by Michael McClure, Charles Olson, Max Finstein, and Robin Blaser. (PS3552 .U75 F562 1973. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

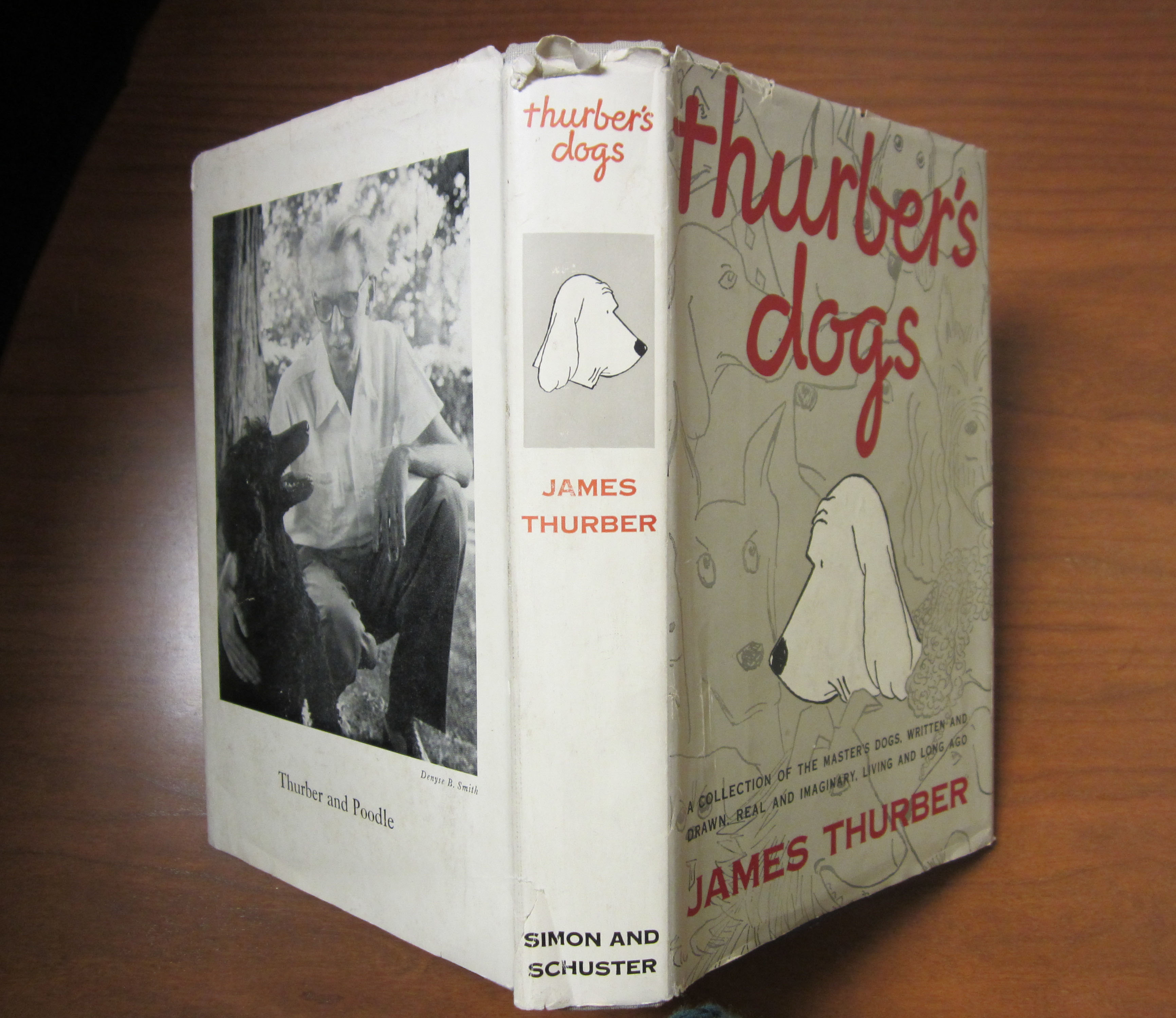

D is for Dog – the Thurber Dog

The humor of James Thurber came across abundantly in his writing, cartoons, and work as editor for The New Yorker magazine. Thurber’s prolific output of writings included The Middle-Aged Man on the Flying Trapeze (1935), Thurber’s Dogs (1955), and many more. Thurber loved dogs, owned and showed dogs, and delighted in drawing dogs. His cartoons of dogs in The New Yorker were renowned for their simplicity and the humor that they conveyed. By the late 1940s, Thurber had lost his eyesight. His drawings were of necessity large and done in crayon.

Contributed by Margaret Hrabe, Reference Coordinator

Thurber’s Dogs: A Collection of the Master’s Dogs, Written and Drawn, Real and Imaginary, Living and Long Ago, 1955. (PS3539 .H94 T54 1955. Gift of Mr. Charles Barham, Jr. Photograph by Donna Stapley.)

Well, D is done! We look forward to meeting you again in two weeks with the letter “E.”