This week we are pleased to present a guest post by English PhD student Annyston Pennington, who works as a curatorial assistant here in Special Collections. Annyston assists with many incoming collections, and we asked them to share their perspective on this fantastic new acquisition after spending several hours unpacking and inventorying its delicate contents. Thanks, Annyston!

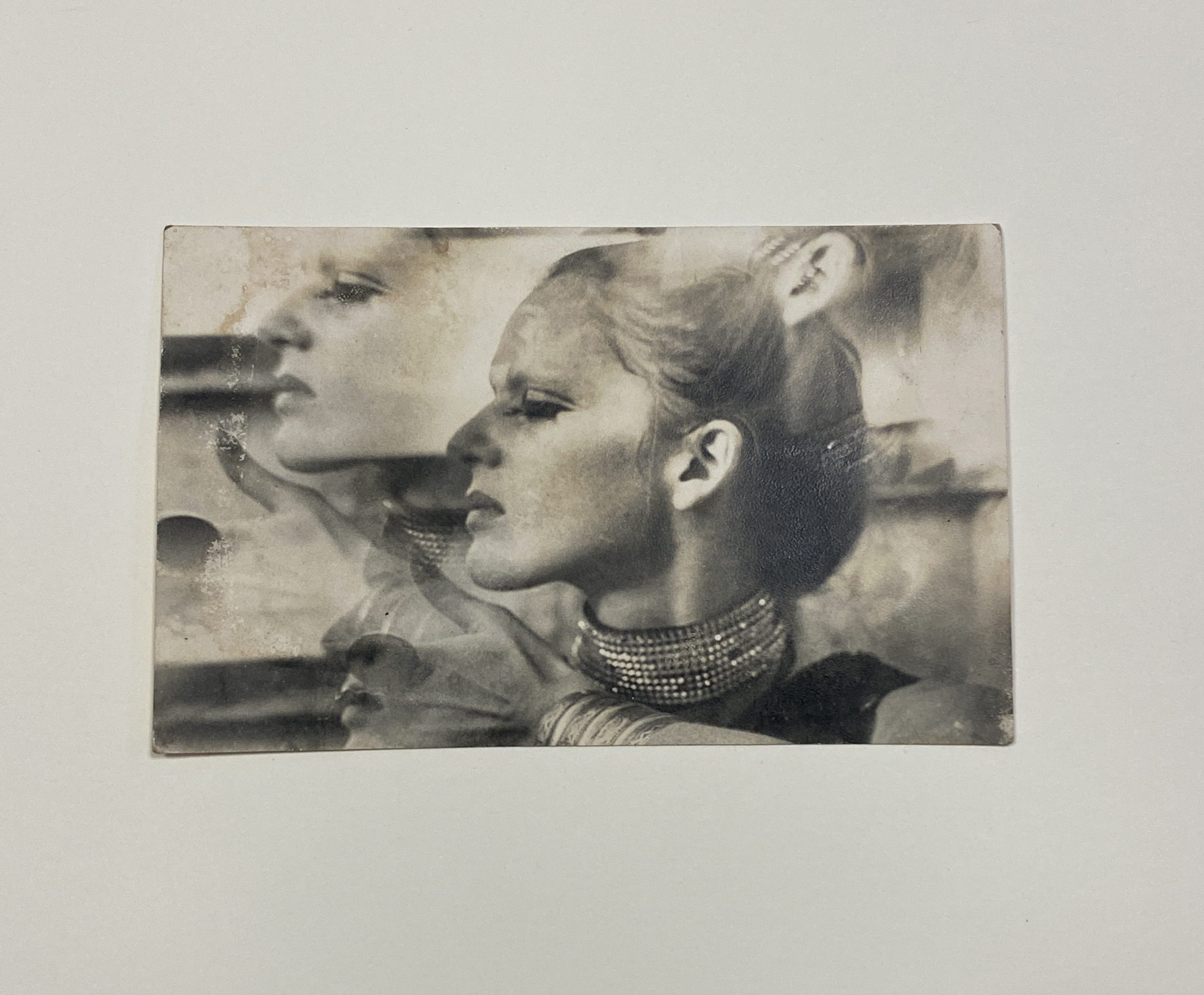

Mylar photograph of Petra Vogt by Ira Cohen, ca. 1970-1979. As a performance artist, Vogt contributed to Cohen’s body of work not as a passive subject but as a multimedia collaborator. MSS 16480, Box 6.2-3

Cracking open a binder of photographs, you meet a cool gaze, her sleek center-part and graphic eye-liner placing the portrait somewhere between 1970s fashion editorials and the beauty influencers of your Instagram feed. Her image emerges amid snapshots of skulls and children on the streets of Kathmandu, as if the world were a stage set for the dark, the fanciful, and the extreme. She is the proto-goth girl of your dreams. Within this recently acquired collection, Petra Vogt peers out, unflinching, from a time at once alien to and rhymed with our own.

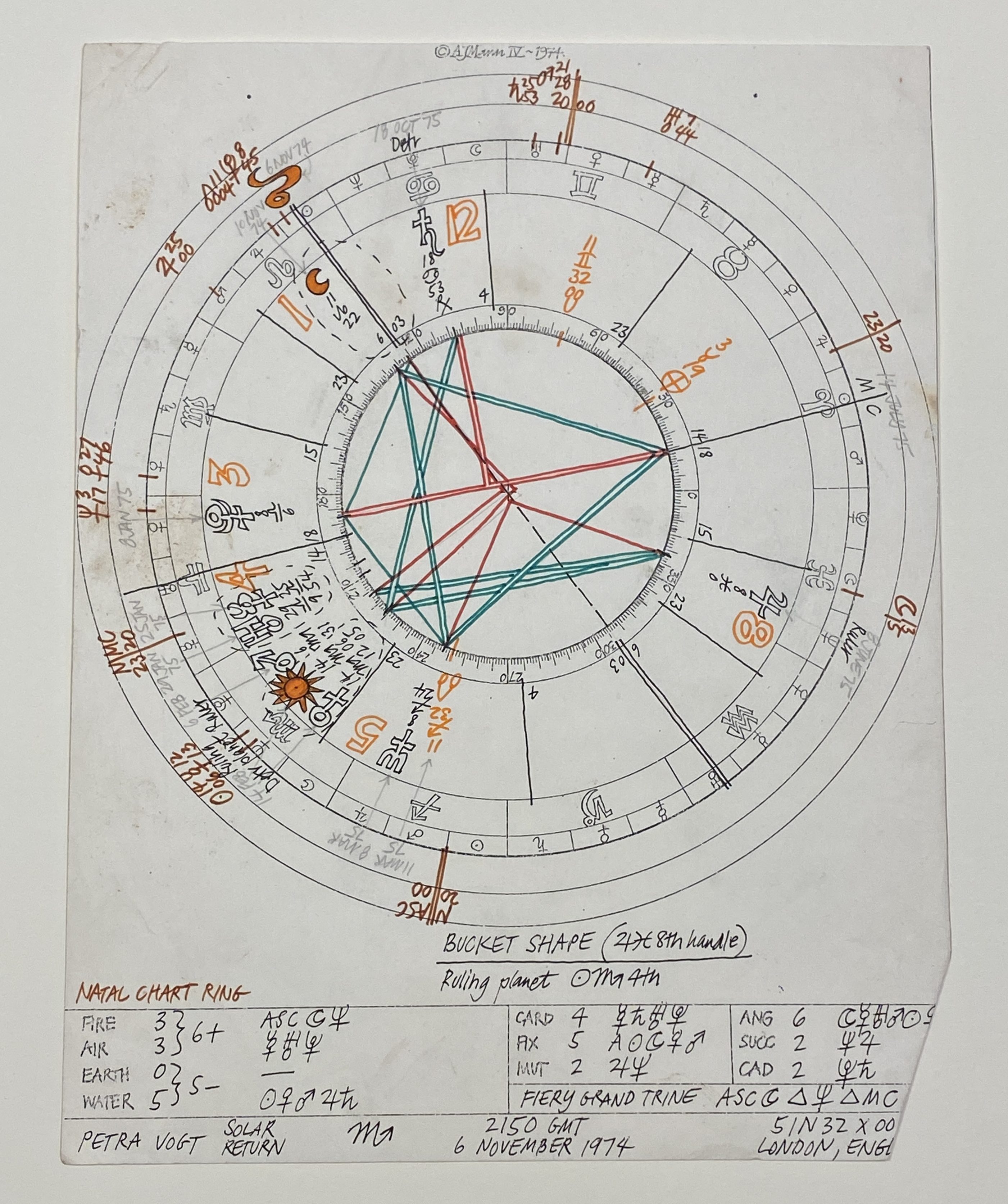

Astrological chart for Petra Vogt by Alden Taylor Mann, 1974. A detailed manuscript explanation of Vogt’s alignments accompanies the chart. MSS 16480, Box 4.6

The personal archive of Petra Vogt, which covers the years 1966-1978 and was acquired during the summer of 2020, is now processed and prepared for researchers to explore. The UVA Library boasts impressive holdings in the poetry and poetics that arose in the post-war era, particularly in the voluminous Marvin Tatum Collection of Contemporary Literature. Vogt’s papers, however, shed new light on the Beat Generation from the perspective of a multidisciplinary, female interlocutor.

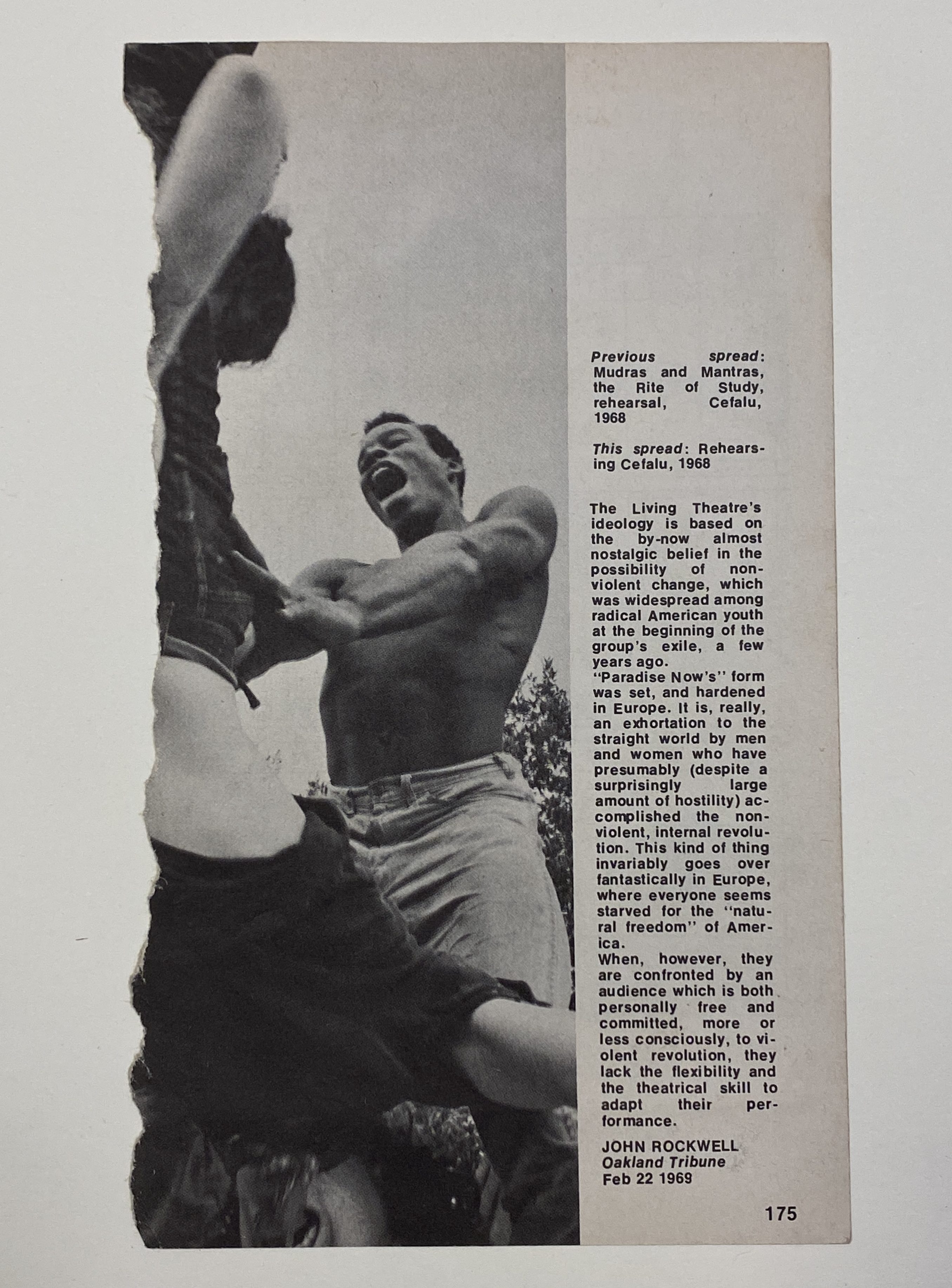

Vogt came of age in Berlin, Germany, developing an artistic and spiritual practice in a world effulgent with the violence, transnational movement, and creative experimentation that mark our contemporary understanding of the twentieth century. In 1962, Vogt joined The Living Theatre, an experimental theatre company, based in New York City, that performed for both American and international audiences. While touring in the United States with The Living Theatre for their performance of “Paradise Now,” Vogt met poet, photographer, and publisher Ira Cohen. One might say, the rest is history, but the papers of Petra Vogt communicate less a traceable narrative than they provide a tantalizing glimpse into the life and mind of an unsung contributor to late-Modernist art.

Magazine clipping featuring review of The Living Theatre’s production of “Paradise Now,” 1969. Petra Vogt performed in the 1968 productions of this play, which Ira Cohen attended. MSS 16480, Box 5.1

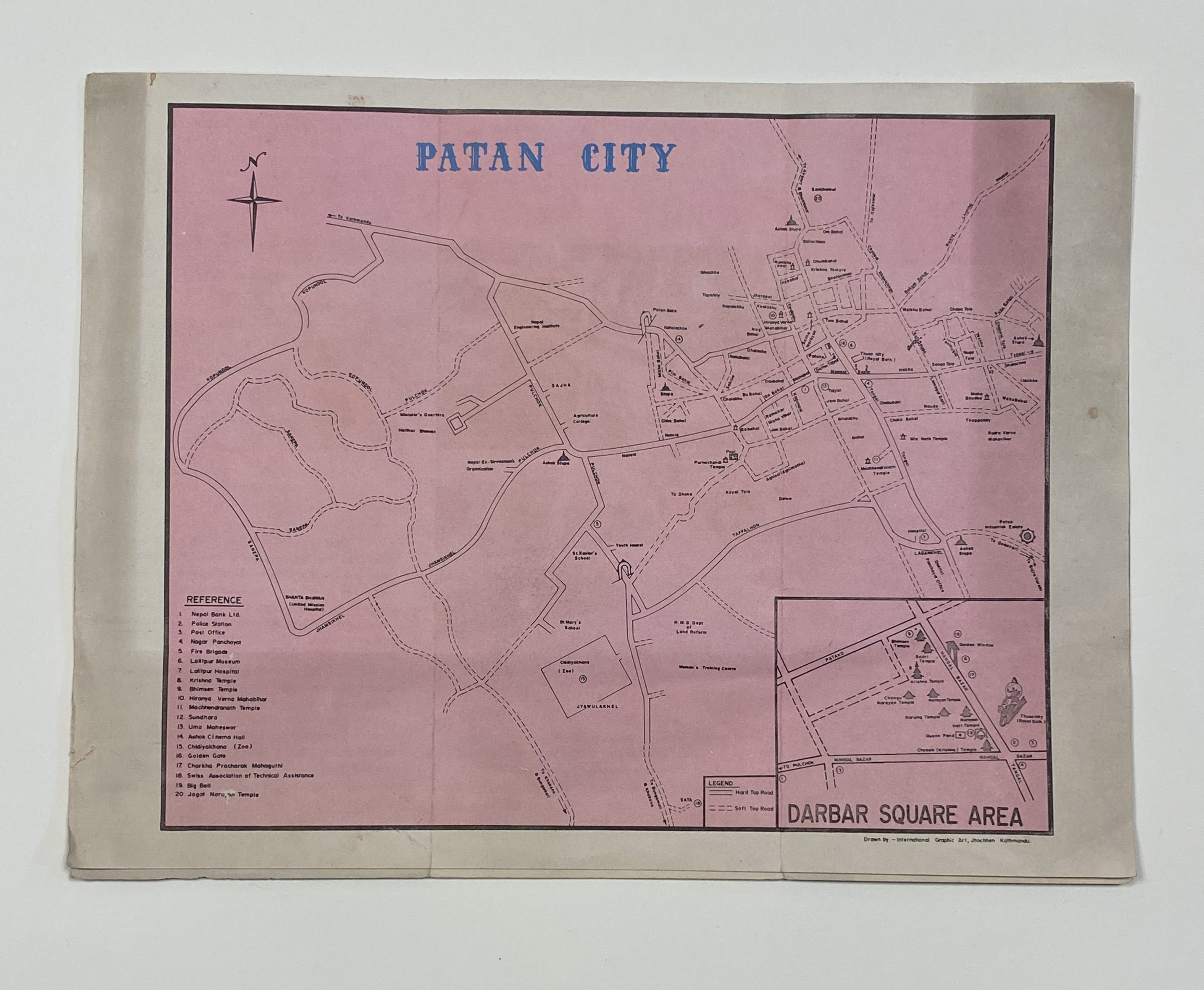

In the early 1970s, Vogt immigrated with Cohen to Nepal, where the pair linked up with other creatives and wanderers, such as Nepalese hippies Jimmy Thapa (born Saraj Prakash Thapa), Trilochan Shrestha, and other notable visitors to “Freak Street,” or Jhocchen Tole, a street in Kathmandu dubbed so for its hippie population. While in Nepal, Vogt expanded her artistic horizons from performance art into literature, visual art, and print material. While often footnoted as a “muse” for Cohen, Petra Vogt was, undoubtedly, a maker.

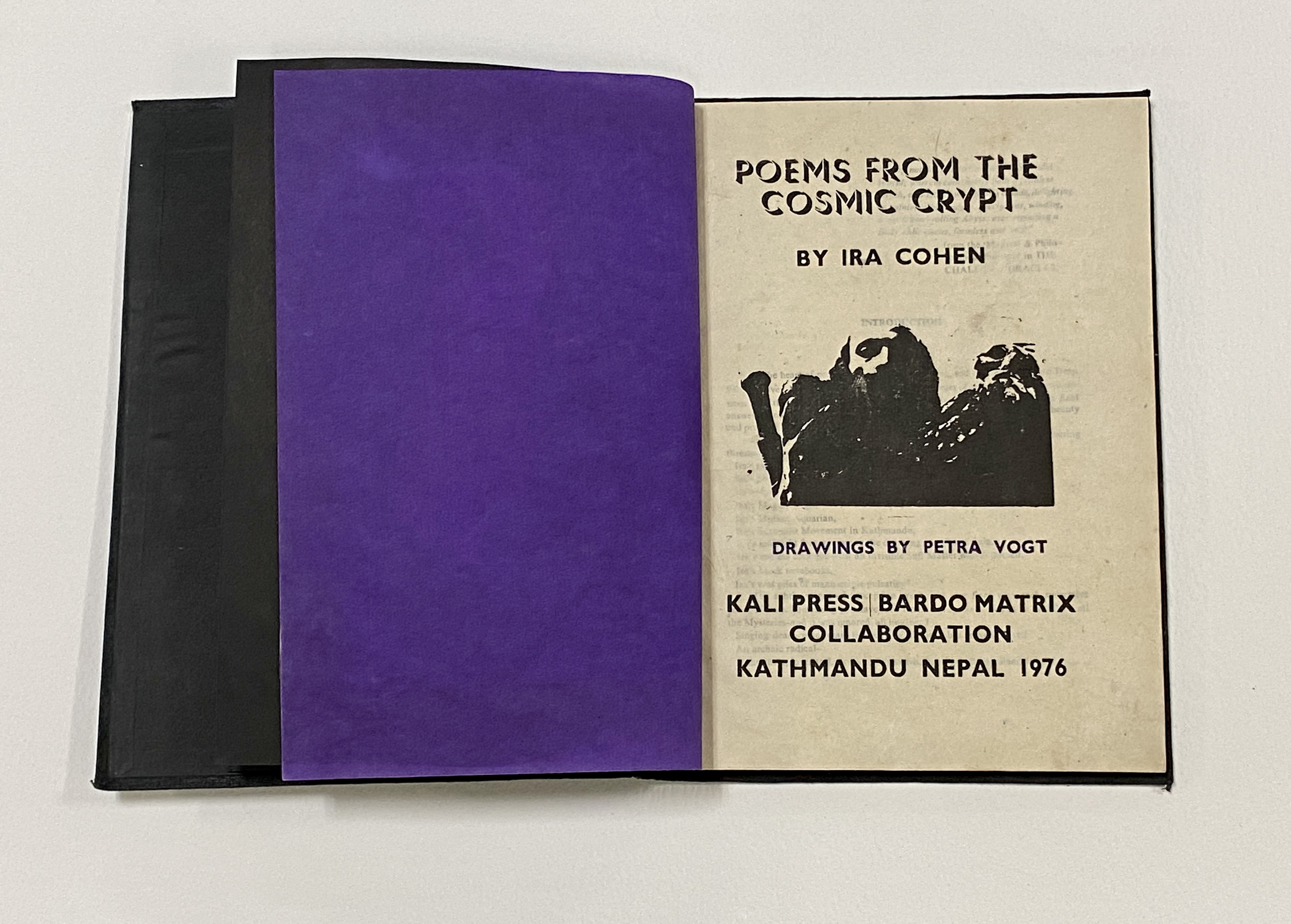

Title spread from “Poems from the Cosmic Crypt,” a Bardo Matrix title, which features black and white illustrations by Vogt, 1976. Cataloging in process: record XX(8890369.1)

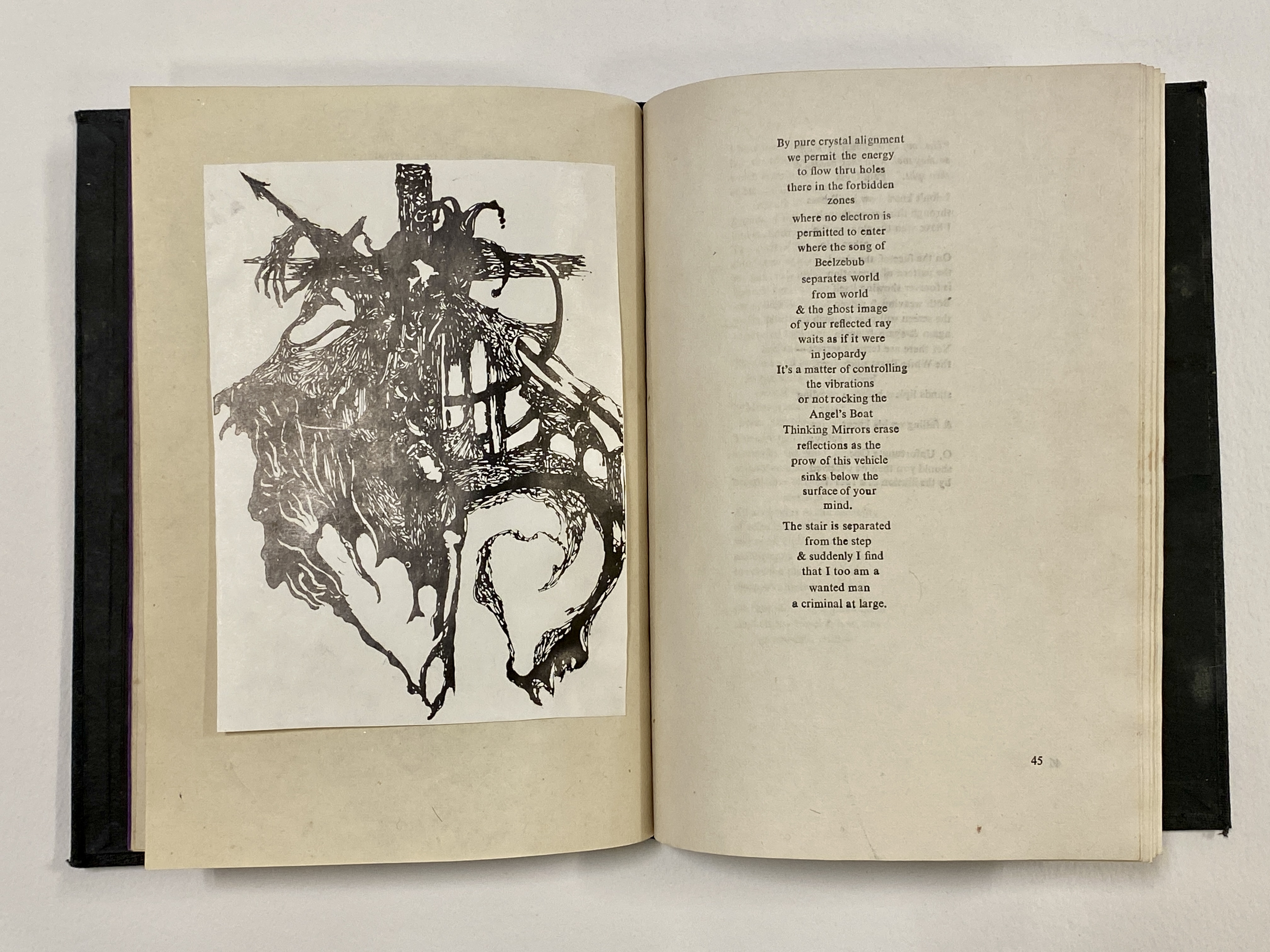

An interior page spread from “Tales from the Cosmic Crypt.”

In her eleven-box archive, drawings, paintings, and collages by Vogt mingle with hand-made scrapbooks and artists’ books, modified commercial texts, and Bardo Matrix Press woodblock prints. In addition to manuscript items, Vogt’s archive includes select Bardo Matrix titles, such as Poems from the Cosmic Crypt, for which she provided pen illustrations to accompany Cohen’s poetry.

Map of “Patan City,” featuring the Darbar Square area, in a tourist brochure for Patan, 1974. “Freak Street,” a hub for artists and hippies during Vogt’s time, falls south of Darbar Square. MSS 16480, Box 5.13

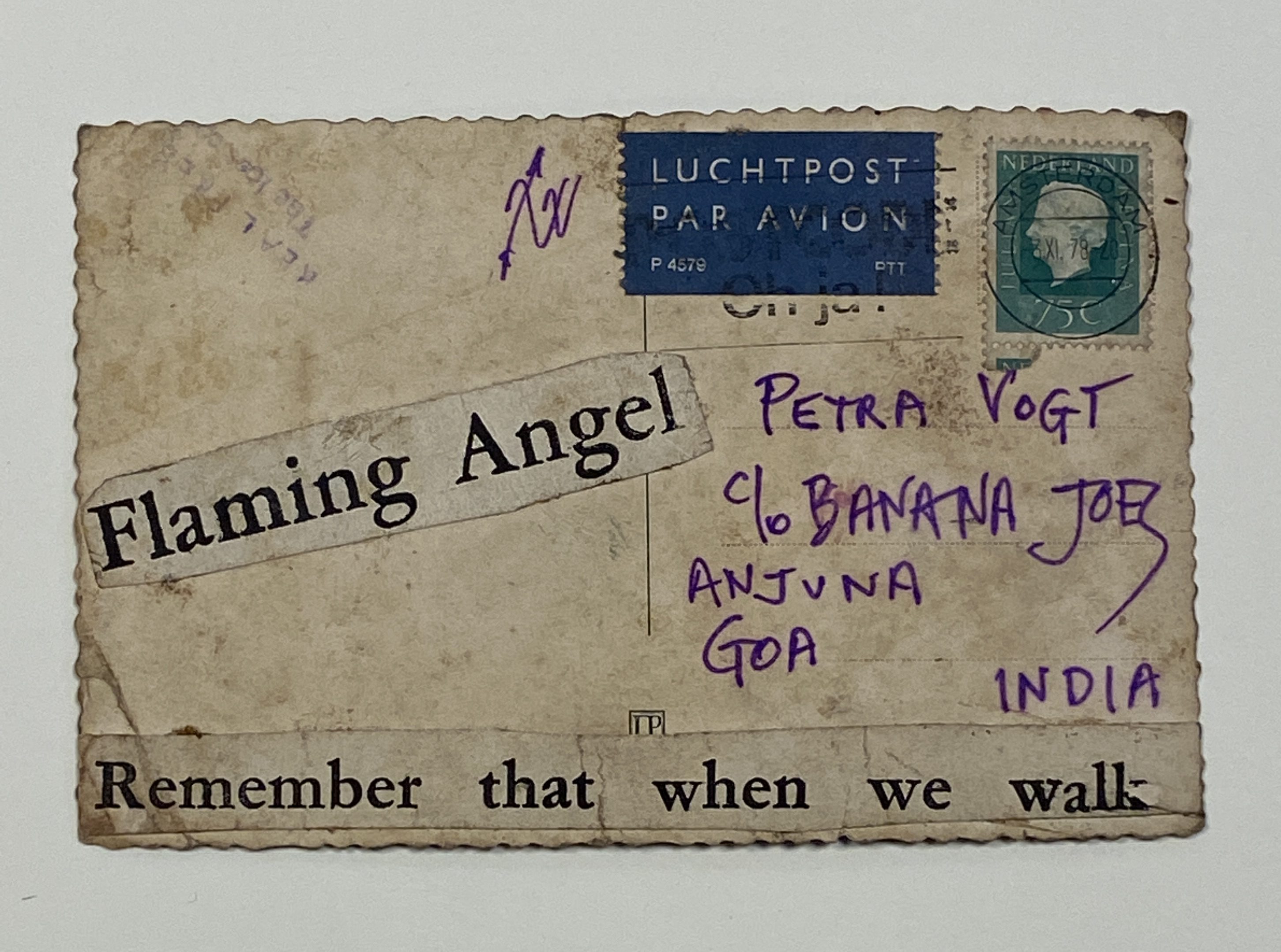

Vogt and Cohen’s lives in Nepal are documented in romantic grayscale and occasional lush color, if the term “document” can encompass both Cohen’s hallucinogenic Mylar photographs and snapshots of the local community’s domestic, public, and funerary rituals. Her papers are aesthetically shocking, even dark, with images of death and the occult filling almost every folder. But human intimacy and tenderness peek through: affectionate notes penned on the backs of polaroids; postcards conveying enigmatic epigrams and well-wishes; hand-made scrapbooks of jewel tone tissue paper hold pages self-adhered with silver leaf; torn-out magazine pages of 70s fashion and fetish gear; and even casual group portraits (with one shot guest-starring Mick Jagger). Candid and staged, curated and altered, Vogt’s archive pays homage to the oddity and beauty of the bohemian everyday, be it newspaper clippings, lotka paper prints, or pictures of Nepalese market stalls. In these papers, we see her artistic impulse to highlight the sensuality latent in such materials.

Petra Vogt’s presence persists, radiant, in her papers. The eccentricity of her biography alone makes the material worth exploring, but it is the collision of the ephemera of an individual life, lived on the outskirts and in constant motion, with the residue of conflicting identities and politics that produces a collection greater than the sum of its parts.

Postcard addressed to Vogt in India, sent care of Banana Joes, 1978. Features Ira Cohen’s glyph in upper-center and reads “Flaming Angel Remember that when we walk” in cut-out print text. MSS 16480 Box 5.9

Note: Thank you to archival processor Sharon Defibaugh of Special Collections Technical Services, who processed and housed the collection and created the magnificent finding aid, all during a pandemic. To see more of the collection, we encourage you to visit our reading room or submit a reference request.