This is the last in a series of four posts, spotlighting the mini-exhibitions of students from USEM 1570: Researching History.

Tales from Under Grounds, Auditorium of the Harrison Institute/Small Special Collections, November 19, 2013. (Photograph by Sanjay Suchak.)

***

Laura McCarthy, Second-Year Student

Laura McCarthy introduces herself at Tales from Under Grounds, November 19, 2013. (Photograph by Sanjay Suchak.)

Martha Jefferson Randolph: Her Time in the Spotlight

Martha Jefferson Randolph was born to Thomas Jefferson and Martha Wayles Skelton in the fall of 1772. As the only child to outlive Thomas Jefferson, Martha Randolph was endowed with the task of continuing her father’s esteemed legacy. During her lifetime, Randolph went above and beyond the duties assigned to the typical southern lady. As a mother of eleven, first lady, alumna of an exclusive Parisian school, and head of the Monticello estate, Randolph lived a life full of ambition, grace, and fortitude.

Draft of Martha Jefferson Randolph’s Will, 1834, from the Papers of the Randolph Family of Edgehill. In 1834, two years before her death, Martha Jefferson Randolph drafted a copy of her will, delineating the recipients of the property she planned to leave behind. These recipients include, but are not limited to, her five daughters, Mr. Coolidge (her son-in-law) and George Randolph (her son). She divides up her funds and other prized possessions, such as her father’s clock and includes her intentions for the futures of her slaves. For example, she states, “To Betsy Hemmings, Sally and Wormley, I wish my children to give their time.” By this, Randolph is indicating that she wishes for these enslaved people to have an informal emancipation which allows them to stay in the state of Virginia, instead of having to leave in one year as in the case of those formally emancipated. (MSS 1397. Image by Petrina Jackson)

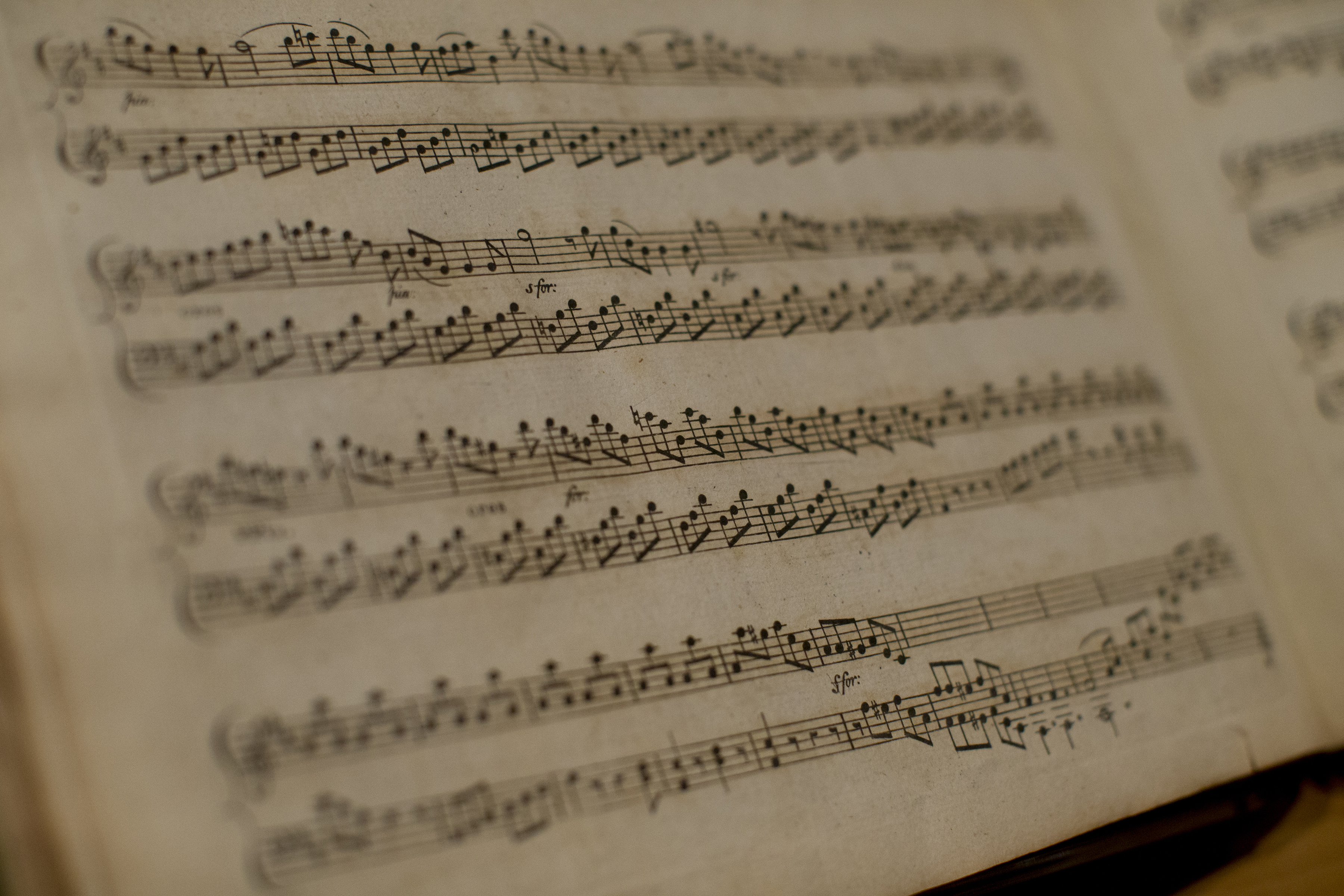

Martha Jefferson Randolph’s Music Book. Monticello Music Collection. Music was an important aspect of the Jefferson family household. Both Thomas Jefferson and his wife Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson were keen on music. For example, while the two were in courtship, Thomas Jefferson presented a pianoforte to Martha Wayles Skelton as a gift. Undoubtedly, the Jefferson’s raised their daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph to respect music in much the same way as they did. Martha Randolph started practicing music when she was 11, and, in 1784, went to Paris to study music along with drawing and literature. This music book owned by Martha Jefferson Randolph contains six Sonatas by Bach and one trio by Mozart. (MSS 3177-a. On Deposit from the Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Photograph by Sanjay Suchak.)

***

Elvera Santos, First-Year Student

Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: You Decide

Displaying several historical resources, this exhibition about the 38-year liaison between Thomas Jefferson and his slave mistress, Sally Hemings, provides an eye opening experience to a debate that has been going on since the late 18th-century. The writings of Jefferson contemporaries and family members, such as Dumas Malone and, Ellen Wayles Randolph discount the relationship. On the other hand, the accounts of other contemporaries, like John Carpenter, John Hartwell Cocke, and John Rutledge support the relationship.

Sally Hemings was the half-sister of Thomas Jefferson’s late wife, Martha Wayles Jefferson. The relationship is believed to have begun in France when Sally Hemings served as the maid to Thomas Jefferson’s daughter. Many say Thomas Jefferson fathered Sally Hemings’s five children who lived past childhood. Whether or not you choose to believe is for you to decide.

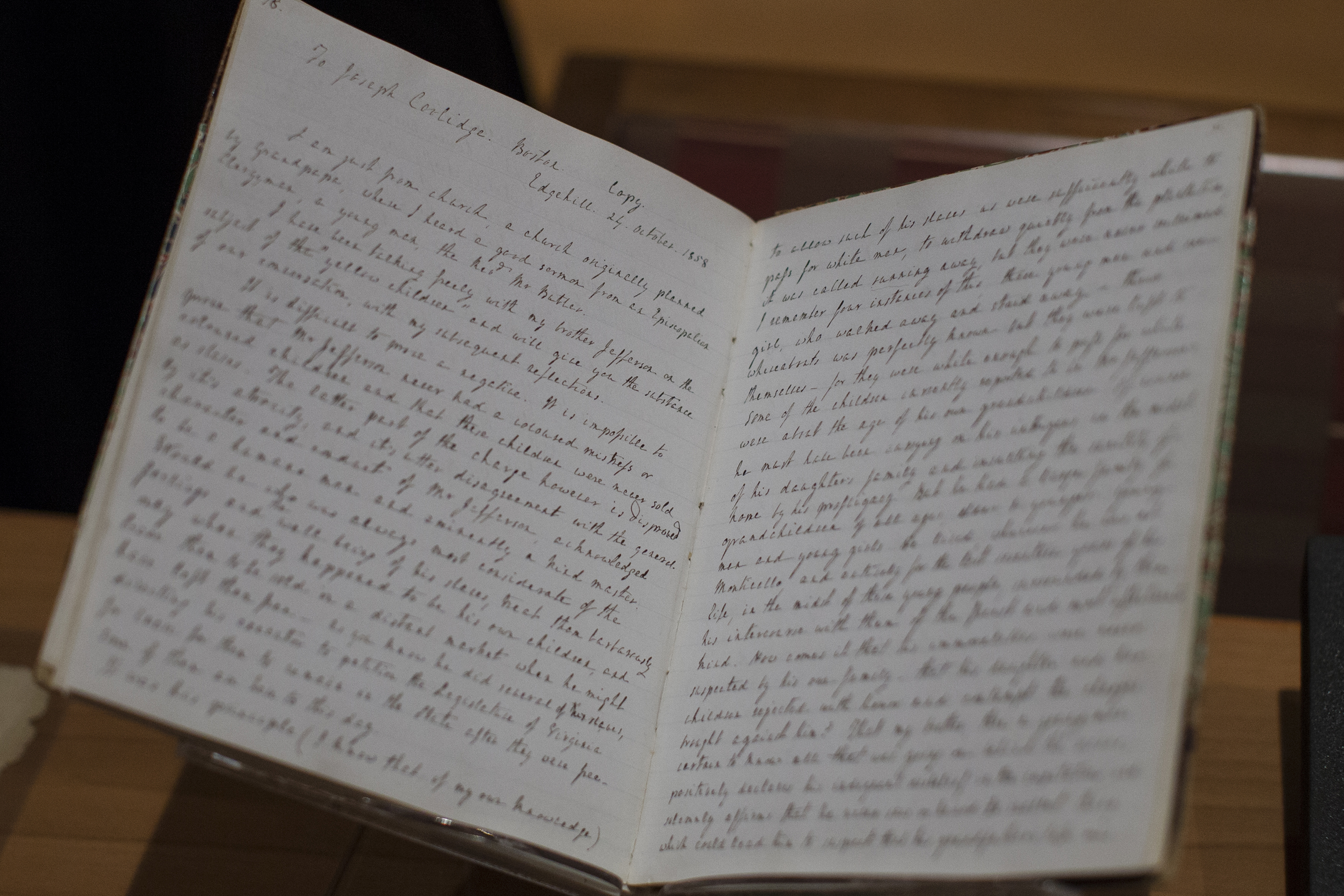

Ellen W. Randolph Coolidge Letter to Joseph Coolidge (her husband). October, 24, 1858. Ellen Wayles Randolph Coolidge was the grand-daughter of Thomas Jefferson. In her letter to her husband, she defends Jefferson against the allegations that he kept a mistress. She calls on the evidence of his character as proof against the allegations. She, furthermore, presents an alternative for explaining Sally Hemings’s children’s’ striking resemblance to Mr. Jefferson, claiming that it was Colonel Carr (a cousin) that fathered Sally Hemings’s children. (MSS 9090. Purchase and Gift. Photograph by Sanjay Suchak.)

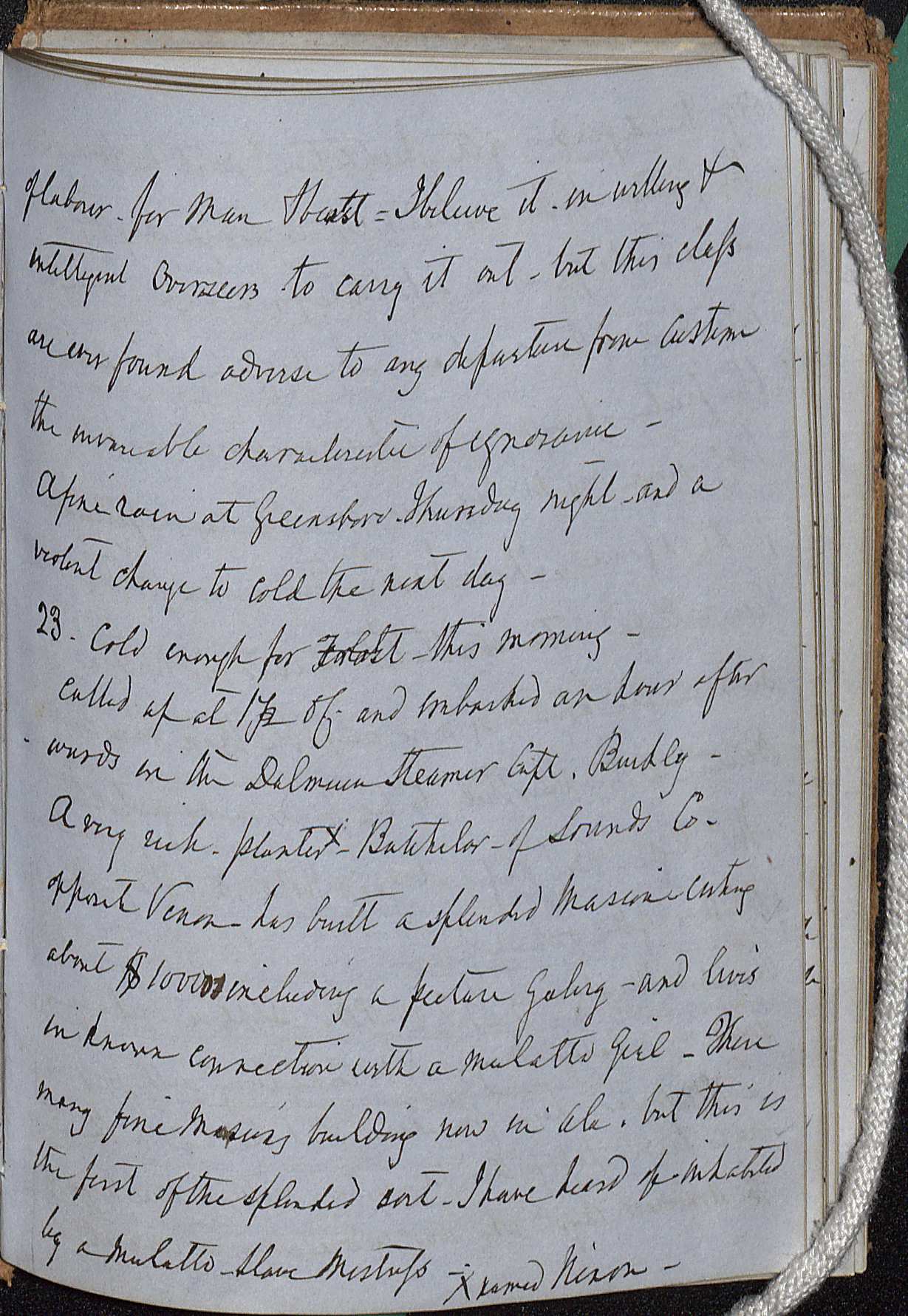

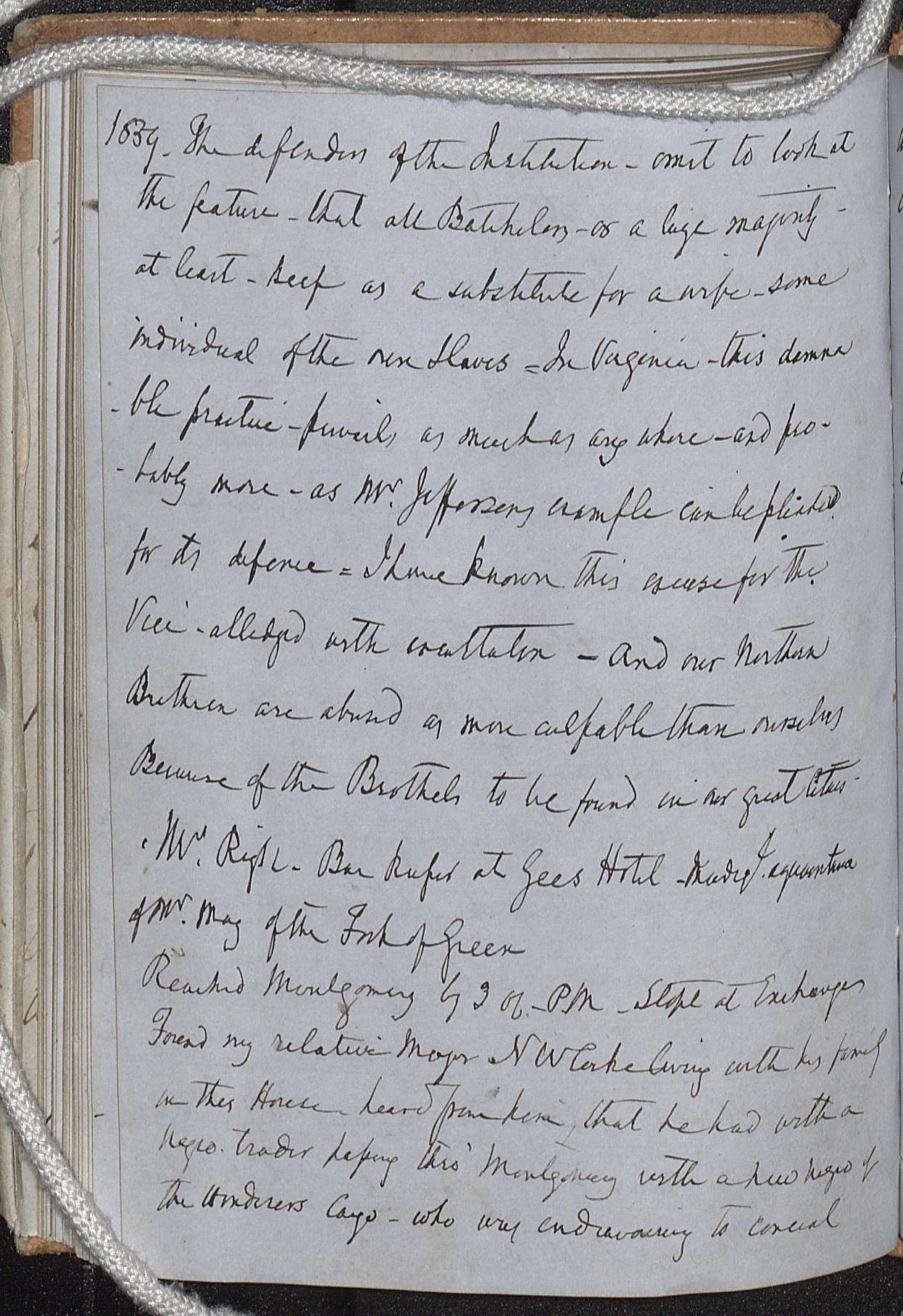

John Hartwell Cocke diary, 23 April 1859. In this entry, John Hartwell Cocke mentions a relationship between Thomas Jefferson and a mulatto, mixed race, slave. He treats the situation as a common and accepted occurrence in Virginia. It is worth noting that the journal entry was recorded 30 years after Thomas Jefferson’s death, so the events mentioned are recollections. (MSS 640. Image by Petrina Jackson.)

John Hartwell Cocke diary, April 23, 1859. In his diary, he writes, “Mr. Jefferson’s notorious example is considered,” in reference to the practice of slave owners taking their female slaves as mistresses. He continued, “In Virginia, this damnable practice prevails as much as anywhere—probably more—as Mr. Jefferson’s example can be pleaded for its defense.” (MSS 640. Image by Petrina Jackson)

***

Chad Hogan, First-Year Student

The Founding of the University of Virginia

In 1817, Thomas Jefferson assembled the first meeting of the Central College Board of Visitors. At this first meeting, Jefferson and the Board passed the new rules and procedures for the College as they pursued the opportunity to create a new University for the state of Virginia. While the University changed its name to the University of Virginia in 1819, Jefferson and the Board continued to create the foundation of the University. The University officially opened on March 7th, 1825 and featured eight different schools for its students to attend. Since its opening, the University of Virginia has used that foundation to continue its growth and attract students to Charlottesville.

This mini-exhibition shows some of the University’s earliest documents and their significance to the opening of the University. It starts with the first minute book of the University of Virginia Board of Visitors, in which Jefferson documents the Board’s first meetings, and ends with the official opening of the University in 1825.

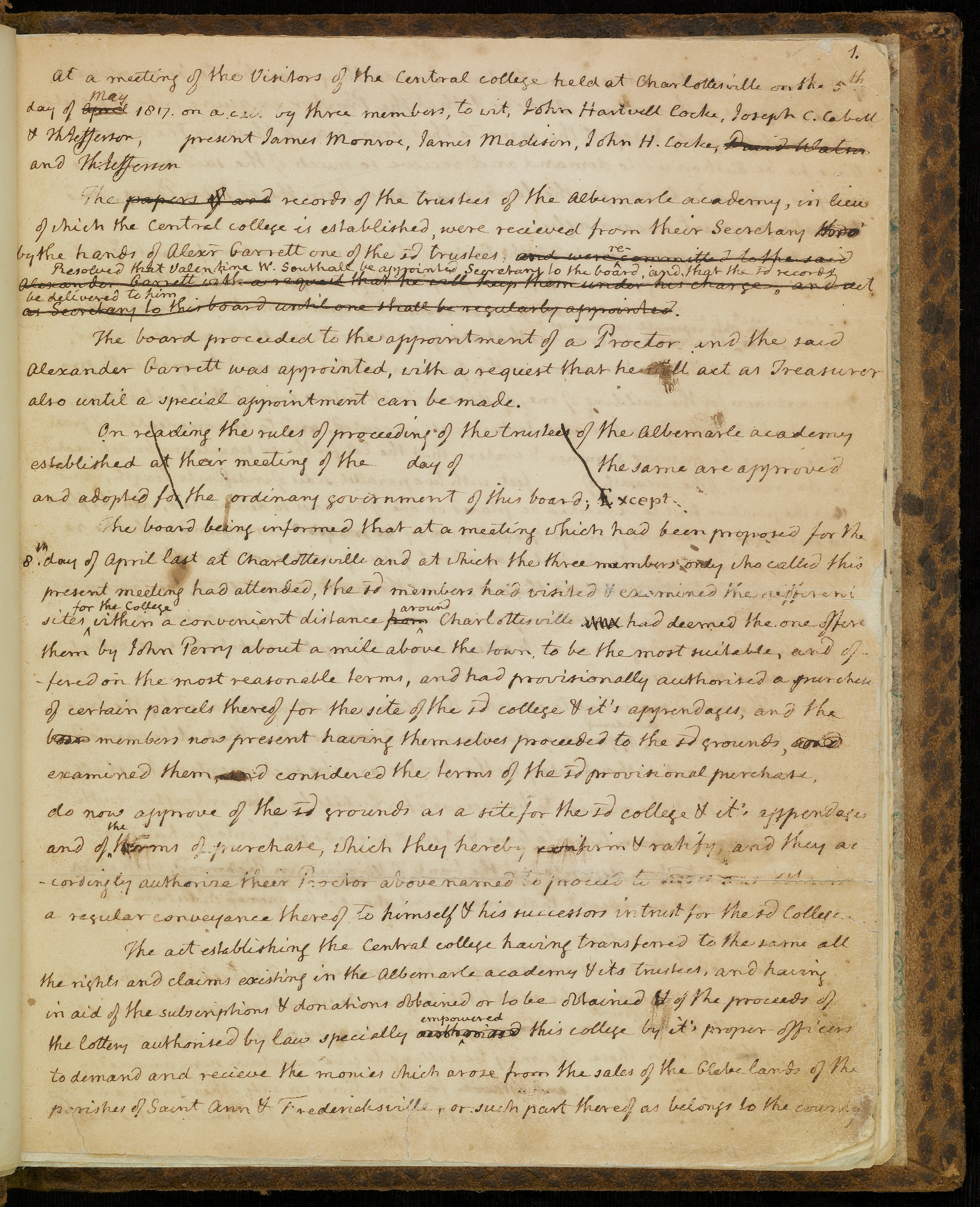

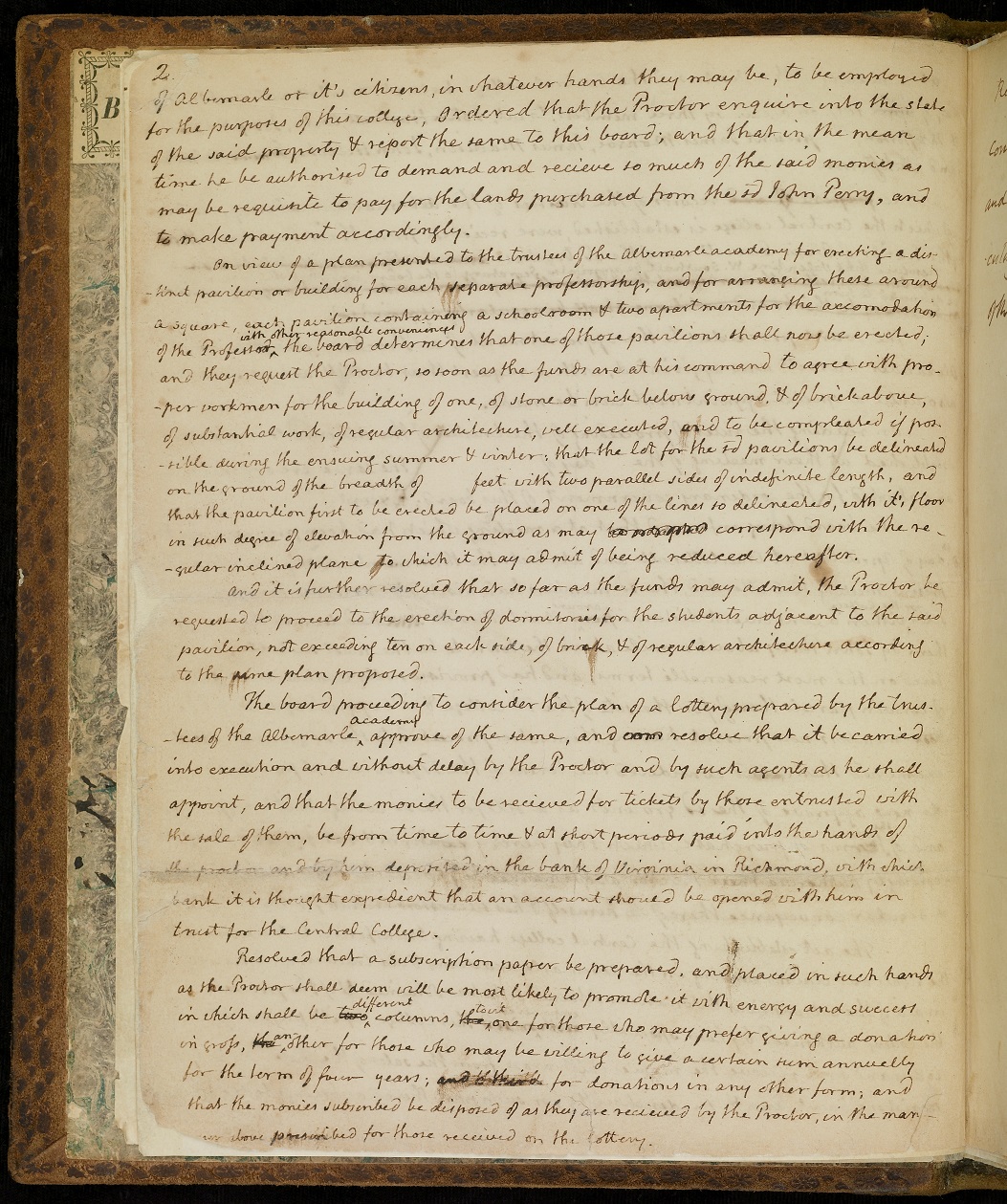

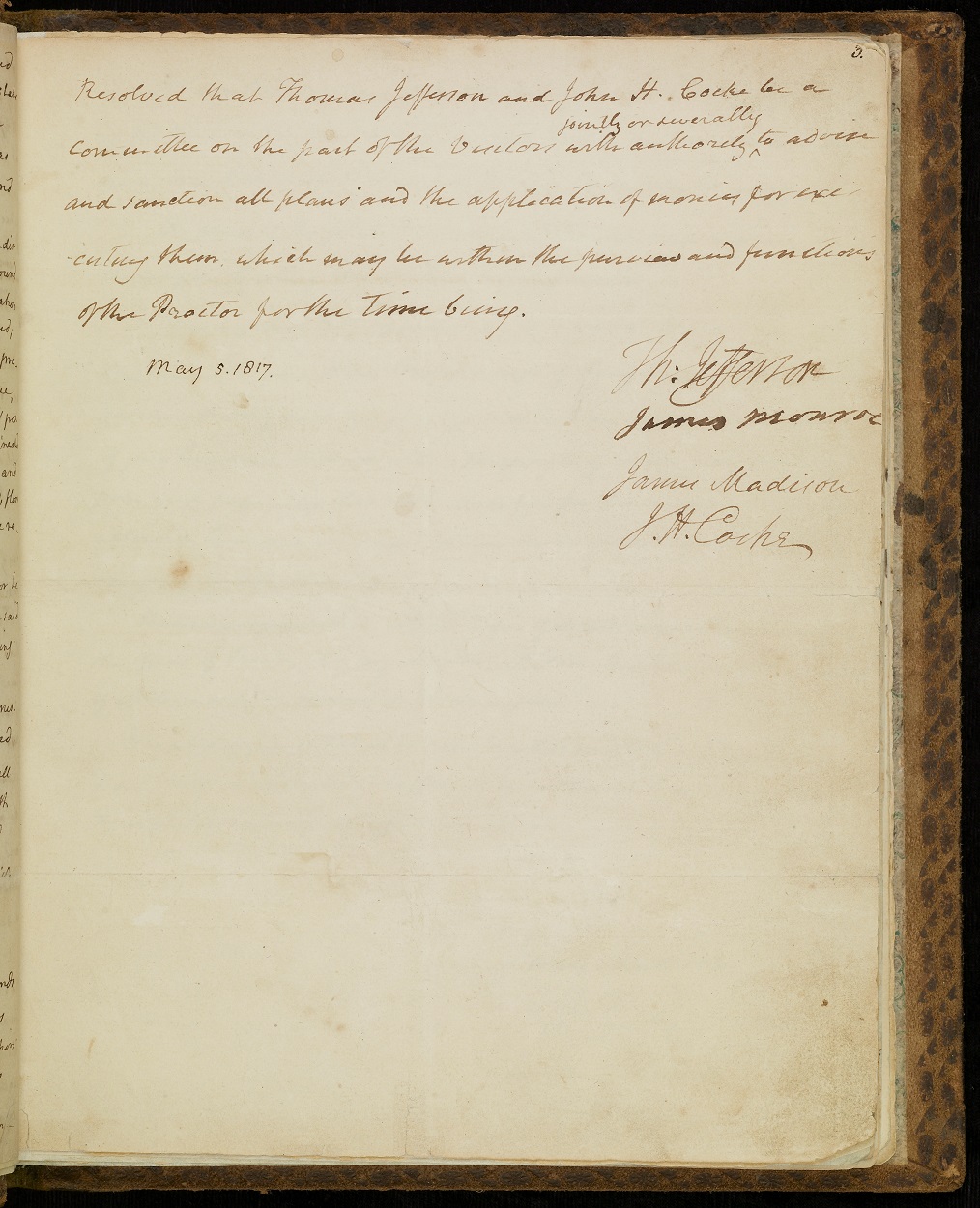

Minute Book of the University of Virginia Board of Visitors, 1817-1828. The Minute Book of the University of Virginia Board of Visitors is a record of the first meetings of the University’s Board of Visitors from 1817-1828. The book, written mostly by Thomas Jefferson, documents the history of the University from its formation as Central College in 1817 to its early years as the University of Virginia in 1828. The book also outlines all of the rules and procedures of the Board and includes the costs of building the University. While the book has been copied to create many facsimiles for the University, Special Collections still owns the original book. (RG-1/1/1.101. University of Virginia Archives. Image by Digitization Services.)

Page two of the Minute Book of the Board of Visitors, written in Thomas Jefferson’s hand, May 5, 1817. (RG-1/1/1.101. University of Virginia Archives. Image by Digitization Services.)

Page three of the Minute Book of the Board of Visitors, written in Jefferson’s hand and signed by Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, James Madison, and John H. Cocke, May 5, 1817. (RG-1/1/1.101. University of Virginia Archives. Image by Digitization Services.)

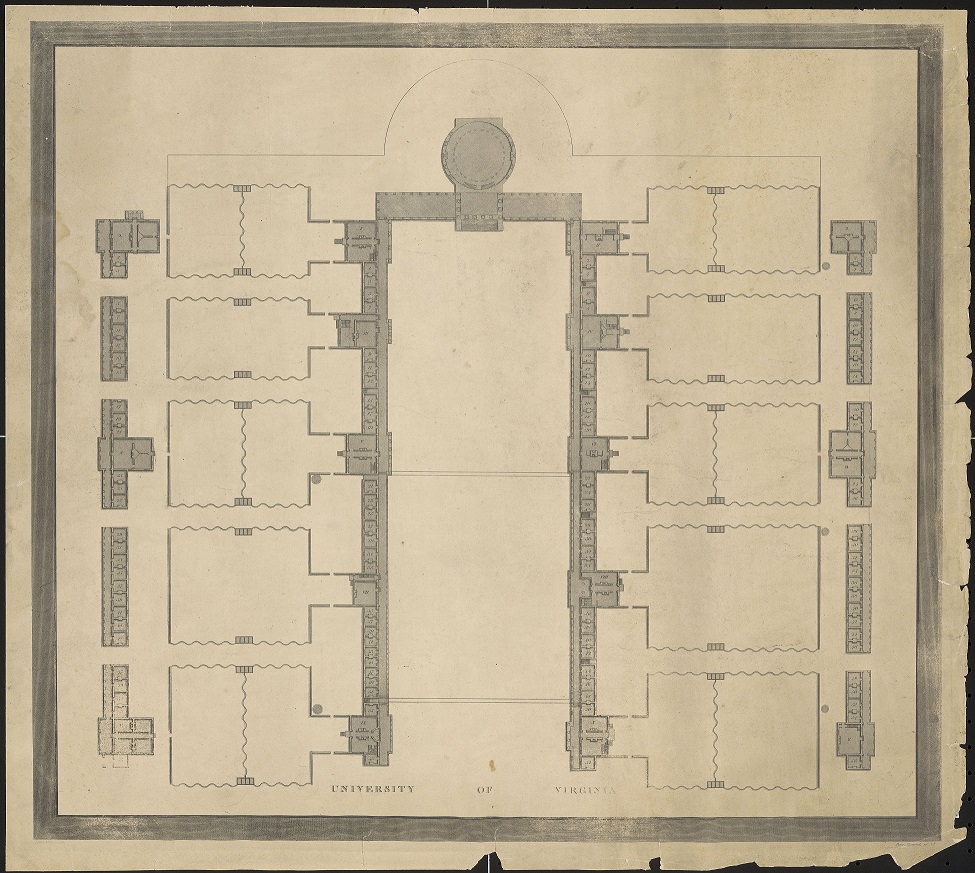

Maverick Plan Engraving of the University of Virginia, 1825. In this 1825 engraving, Peter Maverick outlines one of the final designs for the Academical Village before the opening of the University. The engraving includes a detailed drawing of the Rotunda as well as a hand-written description of all the pavilions. The engraving also displays the layout for student housing. (MSS 171. Image by Digitization Services)

***

Corey Bothwell, First-Year Student

The Civil War Soldiers from the University of Virginia

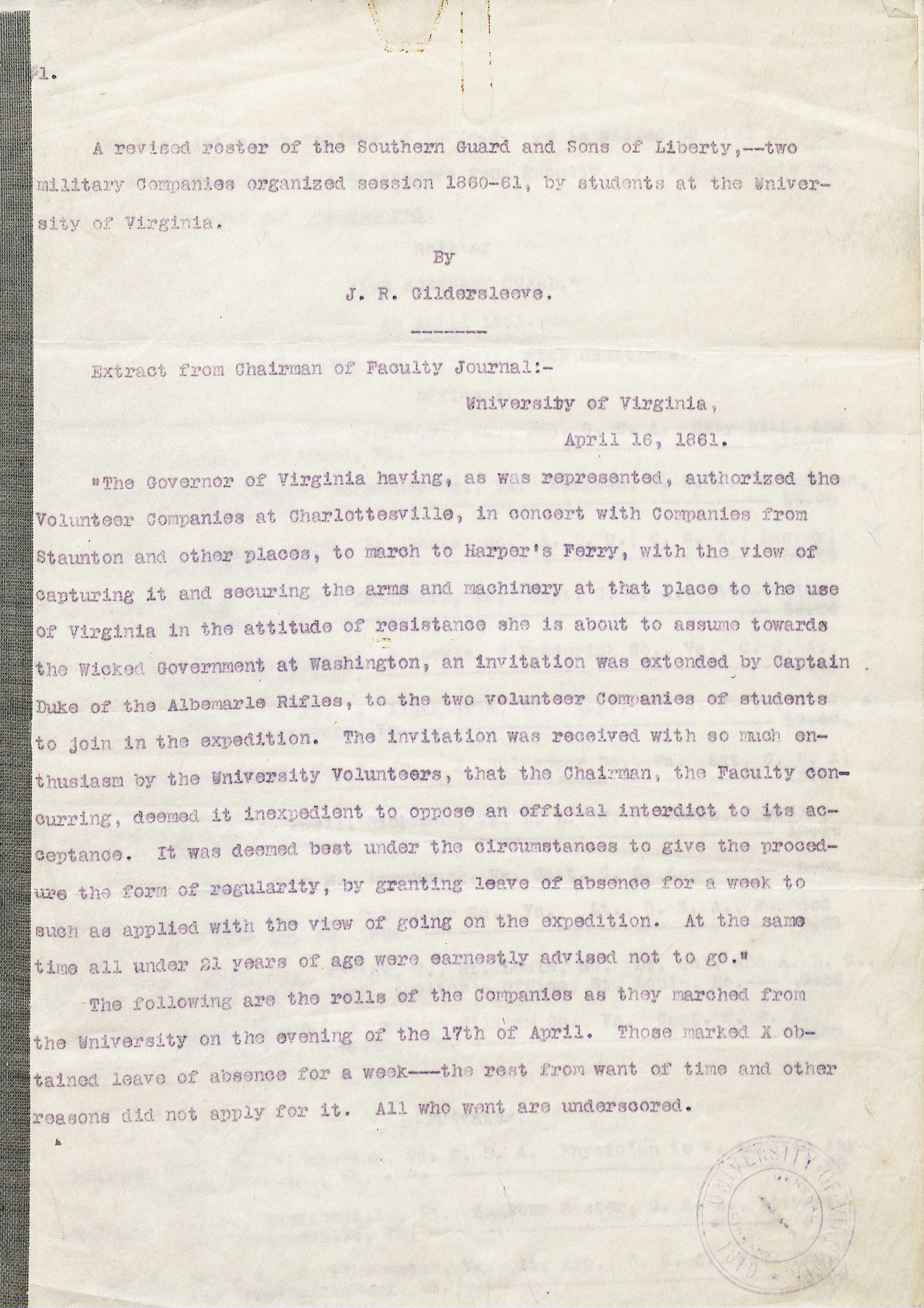

The Civil War, the all-encompassing, defining war of 19th-century America, did not spare its toll on Charlottesville. Regiments of men willing to lay down their lives for the Confederate States of America sprang up in Charlottesville and across the greater Albemarle county area to defend their stake in their hometown and in their land. The University’s own students and faculty were willing to take the risks associated with warfare in order to resist the “Wicked Government at Washington.”

This exhibition highlights a portion of these students and attempts to paint a small portrait of their short time as soldiers. The majority marched on to Harper’s Ferry to attempt to secure the arms held there. They were then ordered back to the University by the governor, as he refused their entrance into state service on account of “too much talent in one body.” Many students did end up making it into state service, and many of these University soldiers would give their lives for what they believed in.

Gildersleeve, J. R. Revised Roster of the Southern Guard and Sons of Liberty, 1911. This roster lists the names of students organized for two military companies during 1860-1861 term – “The Sons of Liberty” and “The Southern Guard”. These “University Volunteers” would join with local Charlottesville forces and other local Confederate companies and march on to Harper’s Ferry where they would attempt to seize control of it. An excerpt from the faculty journal explains how the aim of this raid is to secure advantage for Virginia “in the attitude of resistance she is about to assume towards the Wicked Government at Washington.” (MSS 38-388. Image by Digitization Services)

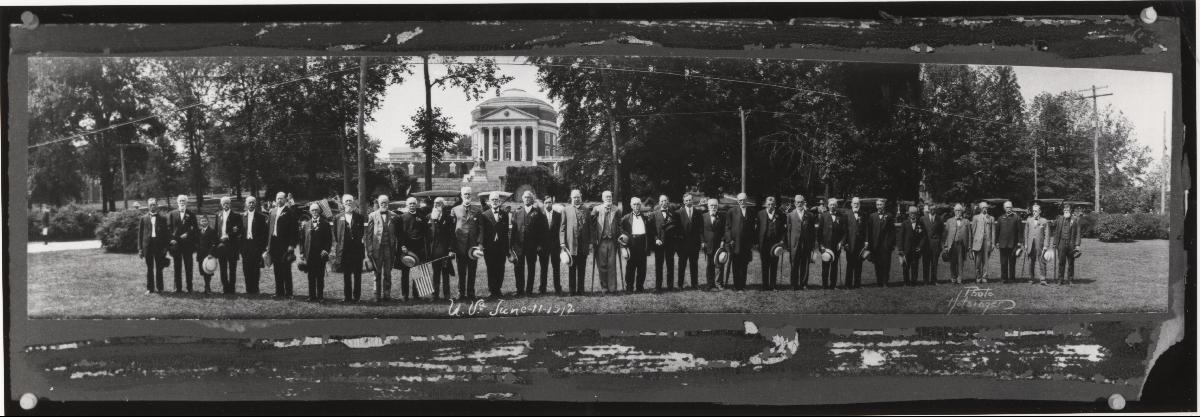

Photograph of a Reunion of University of Virginia Confederate Veterans by Holsinger Studio, June 11, 1912. Pictured here are 28 veterans of the 118 invited to attend a reunion of surviving Confederate Alumni from the years between 1860 and 1865. Note the confederate flag on the car in the background. (RG-30/1/1.801. University of Virginia Visual History Collection. Image by Digitization Services.)