Artists’ books are an important collecting focus here at Special Collections, and the biggest challenge I face in acquiring them is simply, how do I select from the large number of exciting works I see each year? I am always amazed at how many artists find new ways to interrogate the nature and limits of the book and other forms of mass communication, such as newspapers and magazines.

I am always particularly excited when I see an artist’s book that engages with a topic, historical event, or material type in which we have strong holdings and a large research community. Recently, my curiosity was piqued when I heard about artist Bethany Collins’s 2017 book, America: A Hymnal, published by Chicago’s Patron Gallery. Once I learned more, I knew that a copy needed to come here to UVA.

On her website, Collins describes the book as follows:

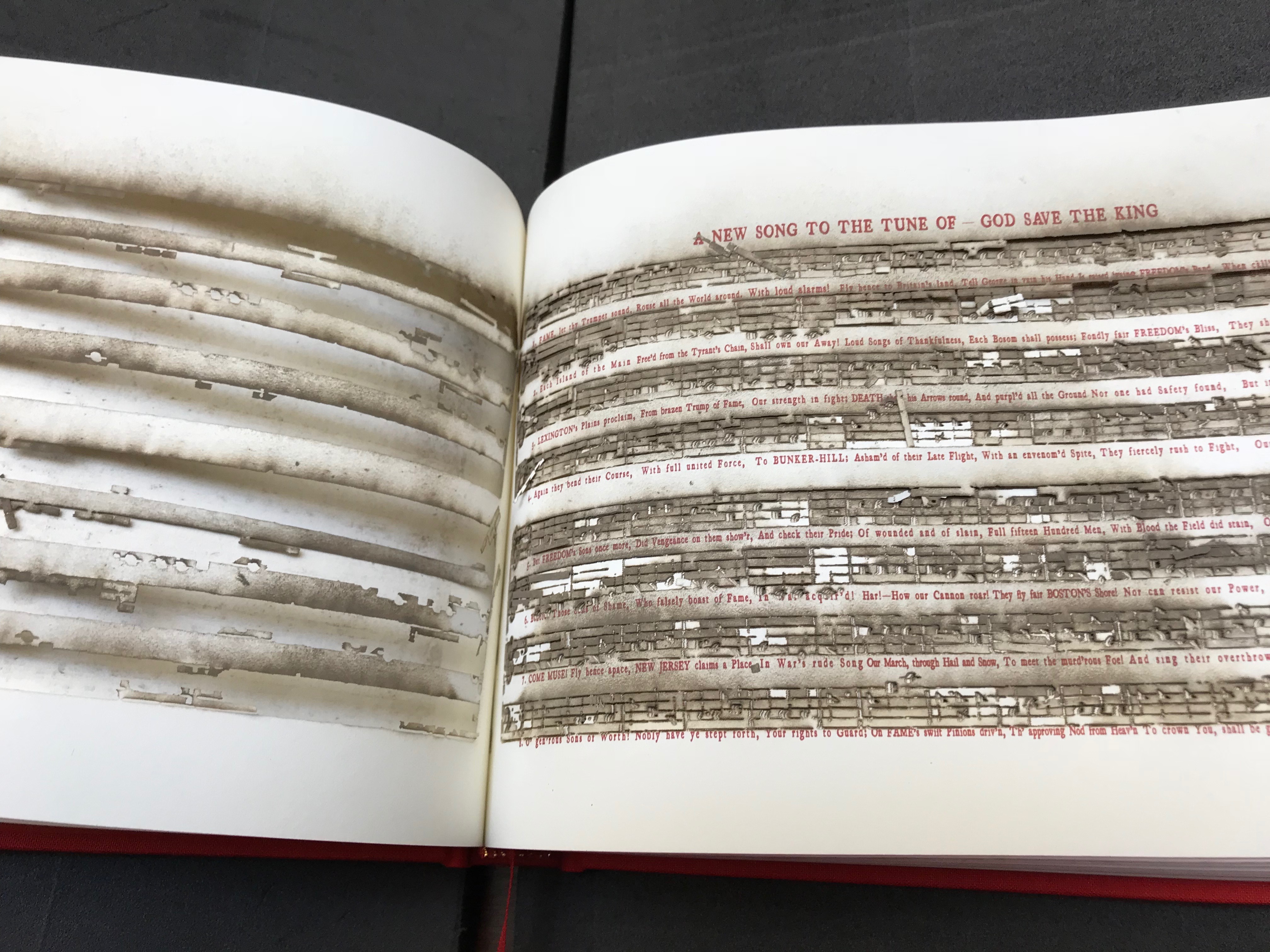

America: A Hymnal is made up of 100 versions of My Country ‘Tis of Thee written from the 18th-20th c. Each re-writing in support of a passionately held cause—from temperance and suffrage to abolition and even the Confederacy— articulates a version of what it means to be American. While the differing lyrics remain legible, the hymnal’s unifying tune has been burned and etched away. Bound and executed in the likeness of a shape note hymnal, in its many lyrical variations, “America: A Hymnal” is a chronological retelling of American history, politics and culture through one song.

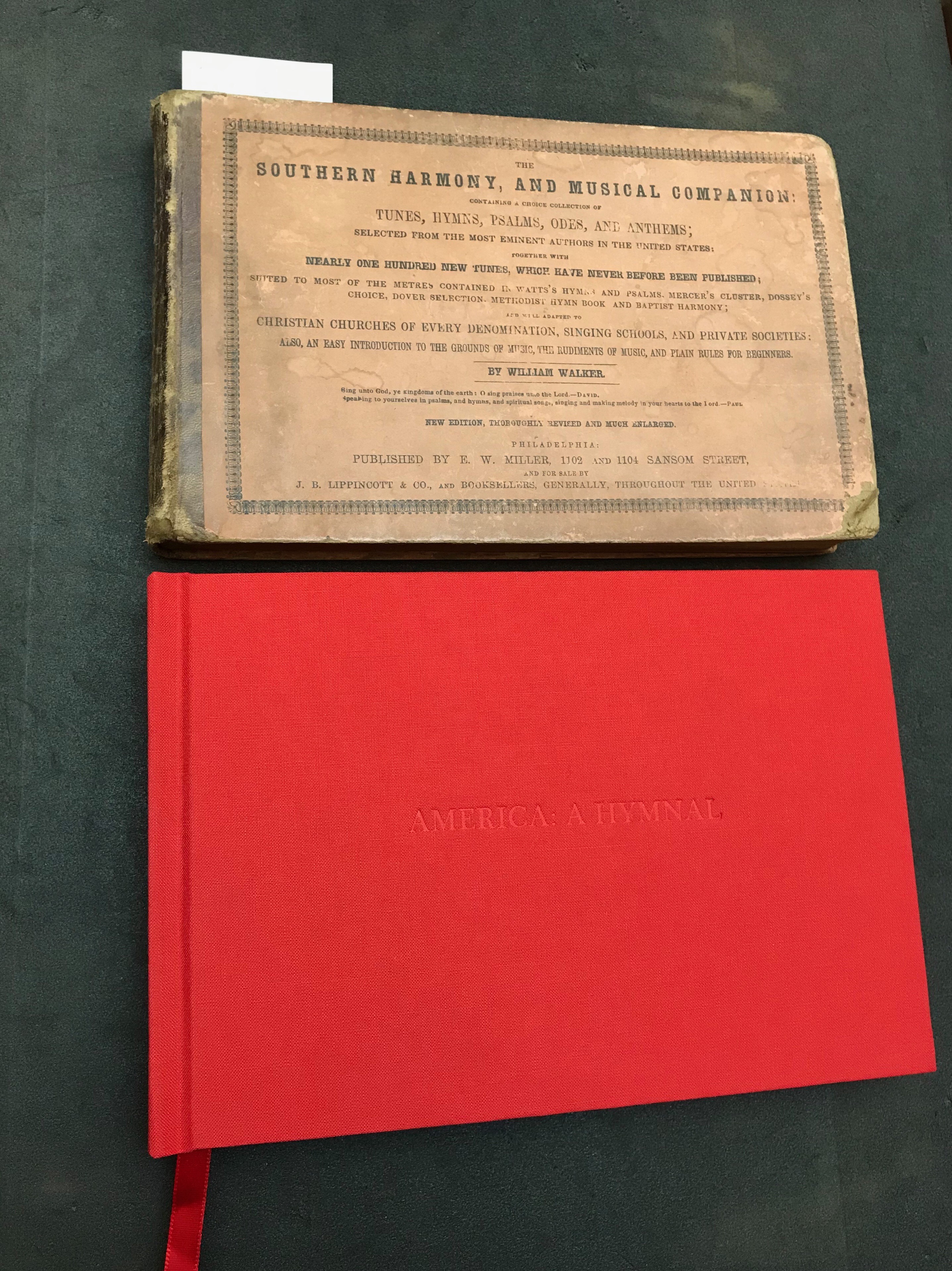

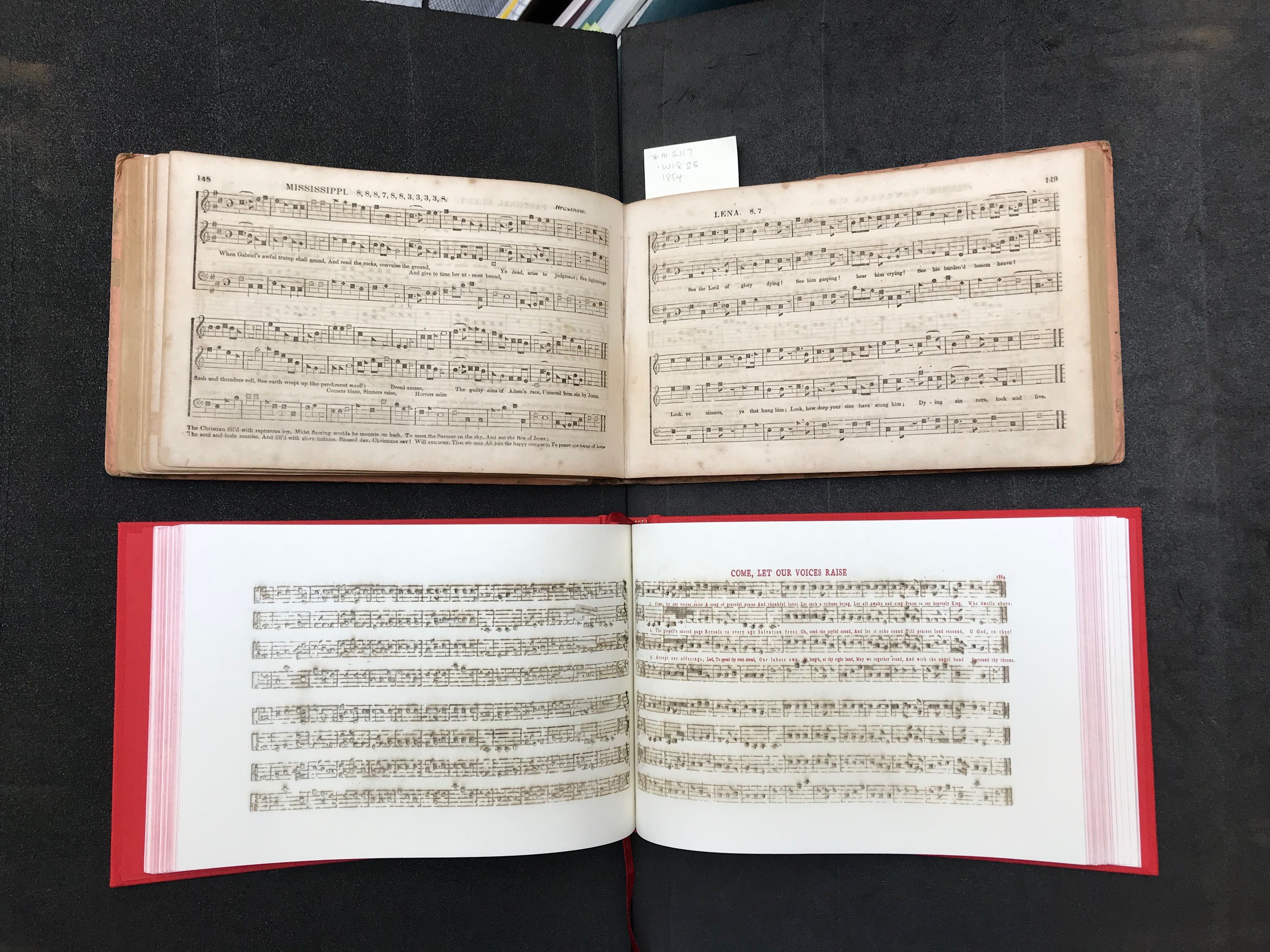

An 1854 “shape note” hymnal from our large collection of such volumes, paired with “America: A Hymnal”. They are about the same size and thickness. (M2117 .W18 S5 1854)

The two books open. A close look reveals that the ink in our 1854 volume has burned lightly into the page, leaving marks somewhat similar to those that Collins achieves with a laser.

One of the things I look for in an artist’s book is a harmony between concept and object. Collins is interested in how the song she represents has changed over time, beginning with its non-American origins as “God Save the King/Queen,” and following with its appropriation in support of the not just the idea of America, but American troops at war, the anti-slavery cause, the temperance movement, women’s rights, and more. The versions are set into the book in chronological order, the date of each appearing at the top right corner of the page. The first time I paged through the book–at the reference desk, so I could share the experience with other Special Collections staff–we all watched with a mix of horror and fascination as the book itself changed over the course of even this first reading.

Just as different generations experienced the tune in the book differently, each reader of this book encounters a different artifact, one changed inherently by the very fact of the encounter. Like a tune, the book is transformed by each “performance.”

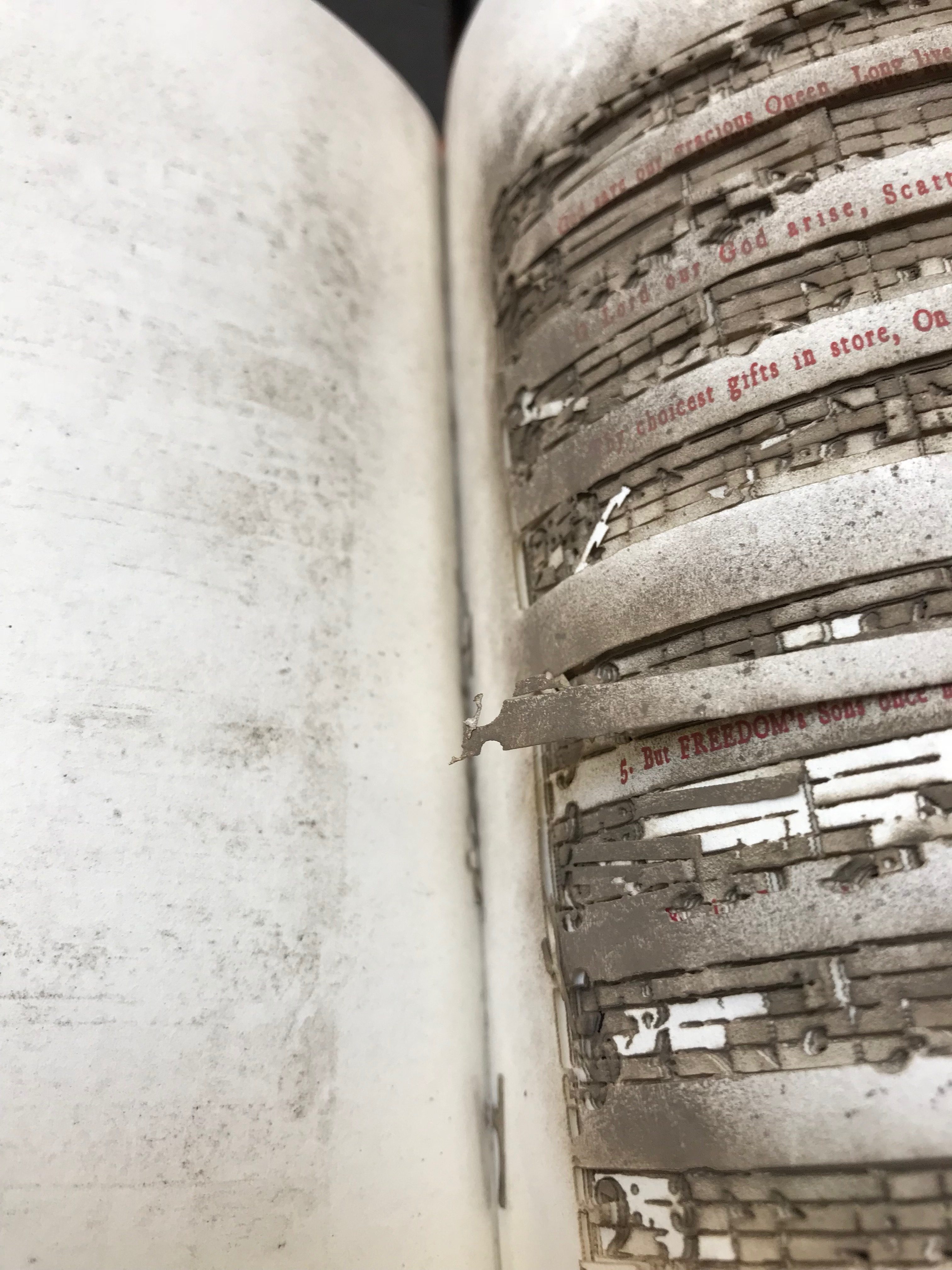

And it is here that the book’s terrifying premise becomes clear. The book–a limited edition of 25, all to be acquired by collectors, museums, and rare books libraries–is very likely be experienced in a rarified environment where preservation of the artifact is paramount. The innocent reader of this book, likely dedicated to these high principles, turns a page only to discover that in doing so, he has caused a bit of singed paper to fall, altering the artifact. To experience the book is to transform the book. Not only is it impossible to preserve this book, its destruction is built in, and the reader becomes accountable for taking it one step further towards an unknowable future condition. And how far does that future go? Will the book eventually become an empty shell, the music gone entirely and only the words remaining?

It is here that the interpretive implications explode outward, providing the opportunities for reflection and a new kind of self-awareness. If the book is a metaphor for America, as its title implies, how does the performance of the book carry out that metaphor? I find myself inclined to a dark interpretation, considering our current political climate: I ask, does this book say we are all implicated in our nation’s destruction, in the hollowing out of our country’s identity, the replacement of our national history with a loss of memory, a collapse of coherence? Even if we do not intend destruction, we each have enacted violence on our national future: we transform it, we rip it apart, the chance weaknesses in the nation’s material responding to our gestures in ways we cannot anticipate. Over time, if the music literally falls away, and all that is left is a set of heavy-handed lyrics, could one extrapolate to say that our nation, over time, is losing its soul, leaving only ideology?

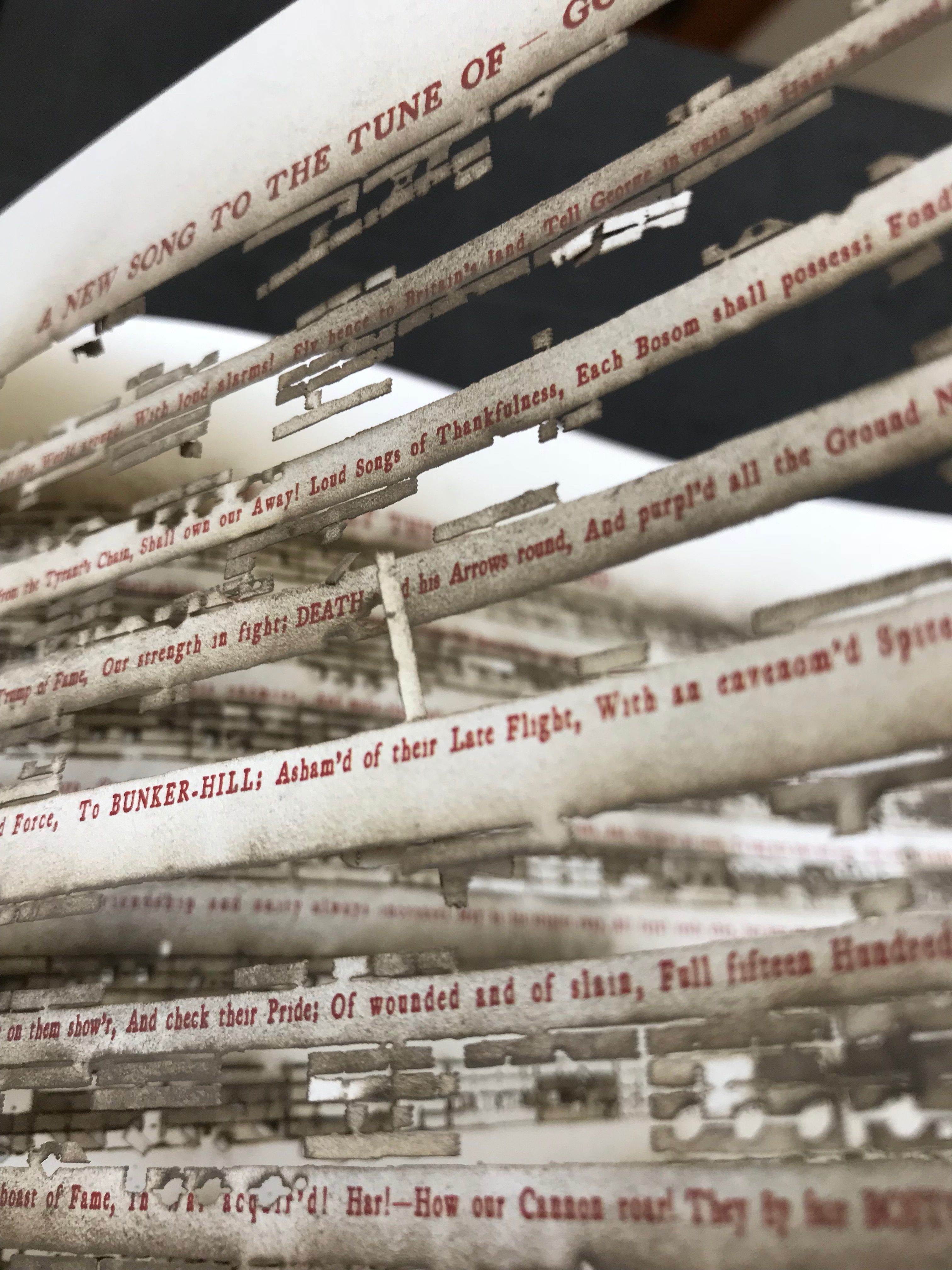

Small lines of paper are about to fall from the page. They are the bits of paper between lasered lines of musical notation.

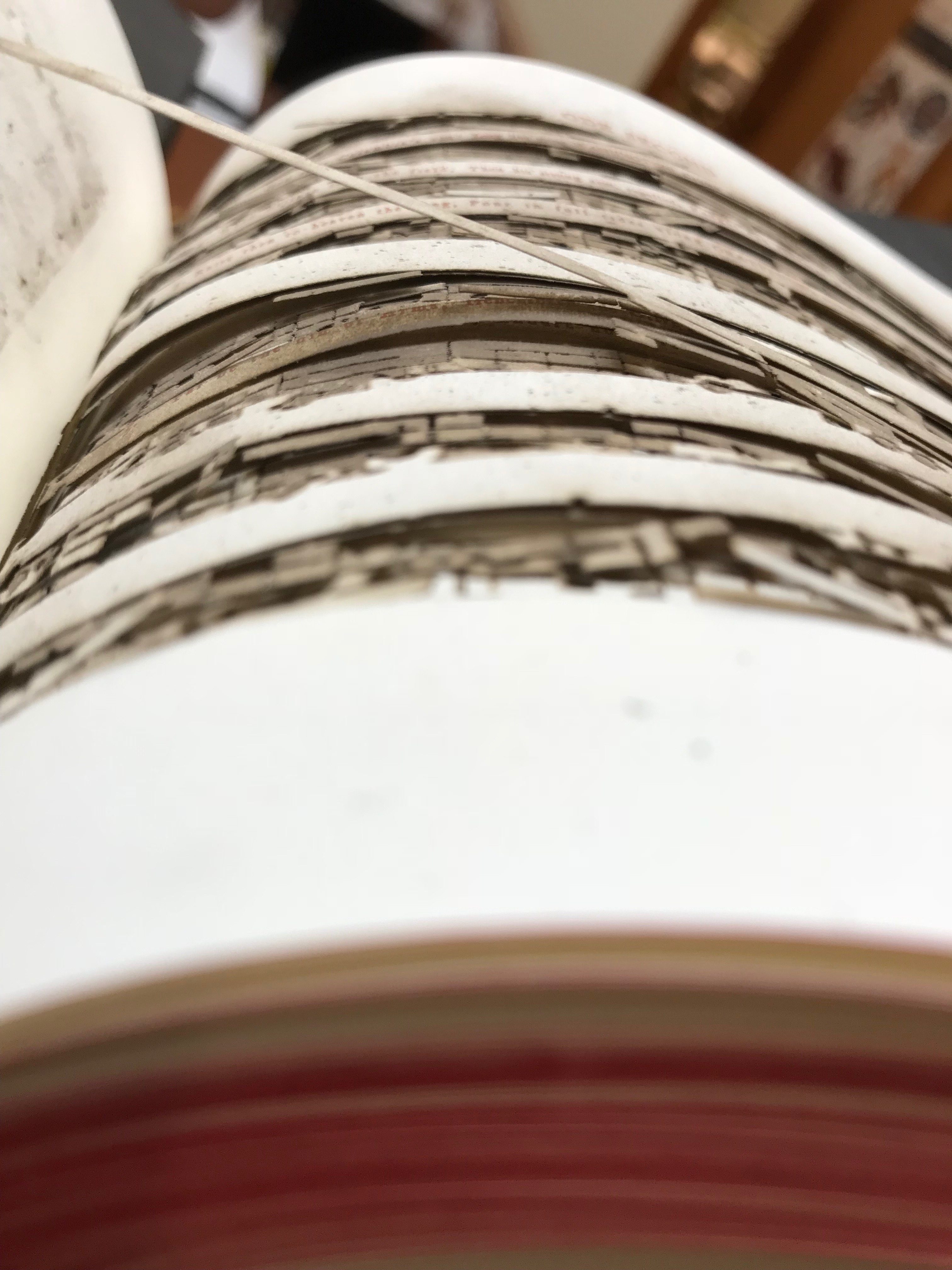

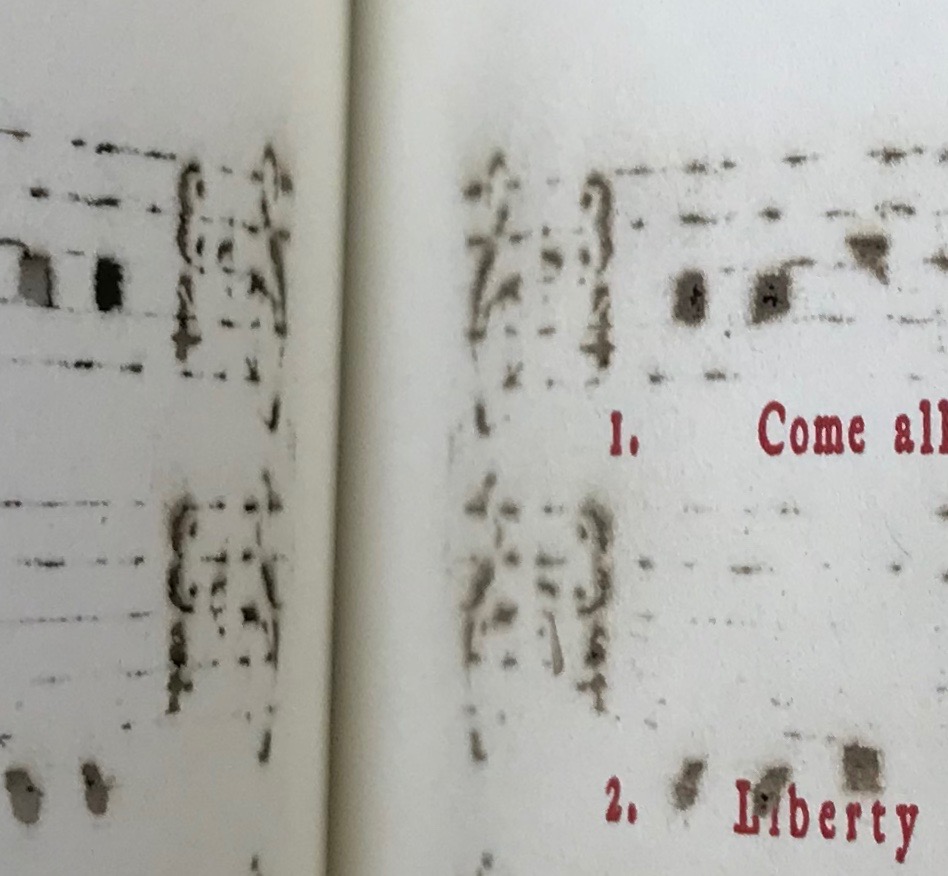

While destruction is inevitable in the future of this entire book as an object, my bleak interpretation is contradicted by the book’s narrative structure, which does not support the idea of a forward movement towards destruction through history. The pages are not all destroyed through the laser-burning. They have been lasered a group at a time, each stack bound in as a group, showing the weakening of the laser’s burn as it burrows through they layers of paper. The video below shows this progression: each page that follows the first is less damaged, eventually leading to a page that looks almost “normal.” There tune is readable, and in many cases, the laser has only left a light burn on the surface of the paper, leaving what almost looks like a printed text.

The verso of this page spread has been burned through, while the recto is intact, though singed.

If the story of the object is that it will deteriorate over time, the story told in its pages is one of repeated rebirth. What begins as violence on the page transforms bit by bit into substance, into clarity, into a song with notes and lyrics. Taking the opening pages as an example (as seen in the video), we see a potent shift. “God Save the King” (1745) has no recognizable music and the page is a landscape littered with damaged bits of paper, the gutter holding scraps that have fallen each time the page is turned. From there, the damage lessens as the laser burn weakens, as follows, tracking the revolution in song:

“A new song to the tune of God Save the King (1777)

Fame let thy trumpet sound (1777)

God Save the Thirteen States (1780)

Washington’s Birthday (1784)

The violence begins anew with a fresh lasering on the next page:

“Ode Second” (1789)

A series of messages appear to emerge through book’s rhythmic sets of pages, from destruction to rebirth over and again, beginning pointedly in this first lasered set with the move from the burned-out king to “Washington’s Birthday.” Whether Collins selected the groupings in order to create small narratives of this kind, or whether they occurred by chance in the combination of the laser’s strength and the musical versions available to Collins, we do not know, and she does not include an explanation for the ordering of the pages beyond their chronology. The reader is left to go back over and again, destroying the pages a bit more each time as she tries to find meaning in the pages’ order, in what is destroyed and what still communicates a complete song.

Inevitable destruction, and a cycle of perpetual rebirth, the music of the nation printed, not with ink, but with the heat and light of a very modern piece of technology. Collins’s book leaves the reader breathless–or holding her breath a bit, afraid both to send fragments flying and to sniff too much of the book’s acrid odor.

A light dust of ash coats the paper and is offset onto the verso of the previous page. Bits of fallen paper rest in the gutter and will be joined by more over time.

For me, this book’s significance is personal as much as it is intellectual. As a child born too late to know the violence and fear of Vietnam, the cynicism of Watergate, I am stunned by the new world we live in today, the unprecedented (for me) state of corruption in our political environment, and corrosion of our national discourse. Yet I am also stunned by the power of activism over the last year. A year ago, I marched in the Women’s March in Atlanta and was buoyed when marchers began singing “This Land is Our Land,” its lyrics botched and then replaced as marchers sought to revive the power of our communal voice. On August 15, 2017, I stood with thousands of members of Charlottesville’s community, who gathered on UVA’s lawn on a sultry night and sang together, quietly, gently, over and over again, “We shall overcome.” We held candles as we sang, thousands of tiny, lovely fairy lights, where days earlier, nasty, ugly, tacky torches had burned, accompanied by chants with no melody. I suppose that one of the things that drew me towards Collins’s book, and one of the reasons that I knew we needed it here in this library, is that we are ourselves in need of art that interprets our current condition, and that urges us to work through it, especially in the moments when we truly feel our nation is falling apart.

As this book falls apart, it opens the reader’s mind to new ways of thinking about its contents and its form. I will end my own reflections there, and hope that other readers–especially musicians, musicologists, and scholars of American religion–will come to the library to page gingerly through this remarkable book, and to reflect on its implications. And I’m looking forward to seeing what America: A Hymnal looks like a year from today, after these readers have transformed it, and when our nation is in a state we cannot yet know.