This post contributed by Elizabeth Nosari, Nau Project Archivist at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. Her work involves processing the John L. Nau III Civil War History Collection, which includes correspondence, diaries, photographs, military records, currency, and printed materials relating to the American Civil War (1861–65).

The Confederates took Fort Sumter following a brief and remarkably bloodless bombardment, April 12–13, 1861, that signaled the beginning of the American Civil War (1861–65). In the aftermath, on April 15, President Lincoln’s call to defend the capital was met by the First Defenders, a group of five volunteer troops from Pennsylvania.1 Among them were the Washington Artillerists from Pottsville, Pennsylvania, which included sixty-five-year-old Nicholas “Nick” Biddle (ca. 1796–1876), who served as the orderly to commanding officer Captain James Wren.2 En route to Washington, D.C., the company arrived in the city of Baltimore in Maryland, a border state, on April 18, 1861. The unarmed soldiers were met by a violent pro-Confederate mob of 2,000 that attacked them with fists, stones, bottles, and “whatever else [the mob] could reach.”3 Biddle was targeted for being a Black man in uniform, and he was reported to have been the first and most violently wounded of the First Defenders.4

When [the mob] saw Nicholas Biddle, an African American in uniform who was treated as an equal by his white comrades…. The mob closed in like “wild wolves,” Captain James Wren, Biddle’s commander, later recorded…. Salvos of bricks pried loose from the streets began to fly through the air. One struck Biddle in the head, knocking him to the ground and leaving a wound that reportedly exposed bone.5

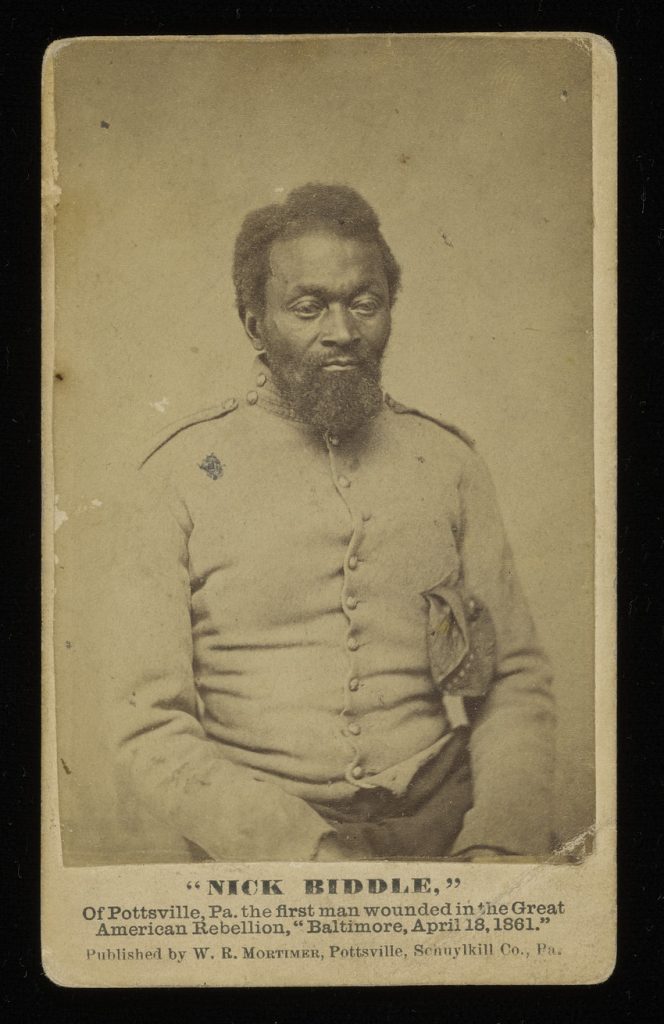

According to historian John D. Hoptak, “Many of the Pennsylvanians present that day believed Biddle was the first man to be struck down by an enemy combatant in the Civil War.”6 Most significantly, however, Biddle, a formerly enslaved person, claimed this distinction for himself and memorialized it by commissioning a carte de visite portrait with W. R. Mortimer (Schuylkill Co., Pa.) in his hometown of Pottsville, Pennsylvania. One of these original photographs, pictured above, is held in the Small Special Collection Library’s John L. Nau III Civil War History Collection. This half-length portrait shows a relatively close-up view of Biddle seated and wearing the uniform of the Washington Artillerists with his kepi hat removed and tucked under his arm. Beneath the image, is the caption, “‘Nick Biddle,’ Of Pottsville, Pa., the first man wounded in the Great American Rebellion, ‘Baltimore, April 18, 1861.” Biddle’s portrait in uniform was radical in many ways—not least because Black men were not legally allowed to enlist in the United States military at the time it was taken in 1861.7

Like many Americans during the Civil War, Biddle chose the carte de visite to make his mark. The advent of photography in the 1840s ushered in the democratization of portraiture, removing it from the sole purview of the elite and the academy. However, early formats like the daguerreotype and ambrotype were still prohibitively expensive for most Americans and limited to a single image developed directly onto a fragile glass plate.8 In contrast, the carte de visite was an accessible, affordable, portable, and easily reproducible aide-mémoire.9 Developed in France by Adolphe-Eugene Disdéri in the 1850s, the format featured an albumen print mounted on a heavier paper the size of a standard business or visiting card.10 By 1860, “cardomania” had arrived and “3,154 Americans earned their living as photographers … [with] at least one in nearly every city and town.”11 Customers, who could purchase multiple prints at a time relatively inexpensively, needed a means of managing and displaying their collections. By 1861, photograph albums also became wildly popular and were filled with portraits of family and friends as well as “mass-produced pictures of … famous people.”12

Americans like Biddle were, for the first time, able to self-consciously create their own identities through photography, “no matter rank or race.”13 As Isidora Stankovic notes, “A single photographic image could reflect an individual’s personality, social standing, intellect—in sum; one’s being—all through the tools of pose, expression, and props.”14 The simple medium of the carte de visite was capable of conveying deeply personal intentions and values, but it was also a form of social currency and a means of commemoration and memory making meant for public consumption, something that, by Stankovic’s account, Biddle seems to have been keenly aware of:

Biddle sold copies of his image at the Great Central Fair in Philadelphia to Americans eager to add his picture to their albums, which were filled with images of the famous and their families. Indeed, a veteran recalled that “‘A photographic album [was] not considered complete in Pottsville without the picture of the man whose blood was first spilled in the beginning of the war.15

The collective importance of photographic images in the nineteenth-century public consciousness cannot be underestimated; and portraits of Black Americans were highly influential, marking a shift in the visual and political culture of the United States. Leading abolitionist and intellectual Frederick Douglass (ca. 1817–1895), a contemporary of Biddle’s, was a forerunner in his use of photographic portraiture to support the abolition movement. Douglass wrote extensively about the democratizing power of photography, and he arguably “defined himself as a free man and citizen as much through his portraits as his words.”16 As Maurice O. Wallace observes, uplifting photographic portraits in the public sphere led the way in introducing Black Americans as a “new national subject” and part of the “imagined body politic.”17 Within this wider trend, according to Wallace, Black soldiering and “the popularity and proliferation of black soldier portraits” like Biddle’s played a key role in “the genesis of African American manhood as a coherent category of civil identity and experience.”18

1 Wikipedia, s.v., “Pennsylvania First Defenders,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pennsylvania_First_Defenders, accessed October 11, 2022.

2 John D. Hoptak, “Nicholas Biddle: The Civil War’s First Blood,” HISTORYNET, October 3, 2008, https://www.historynet.com/nicholas-biddle-first-blood/, accessed October 11, 2022.

3 Hoptak, “Nicholas Biddle.”

4 Hoptak, “Nicholas Biddle.”

5 Hoptak, “Nicholas Biddle.”

6 Hoptak, “Nicholas Biddle.”

7 It was not until the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and subsequent creation of the segregated United States Colored Troops (USCT) regiments that Black men were legally allowed to fight in the Civil War. See Wikipedia, s.v., “United States Colored Troops,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Colored_Troops#The_Confiscation_Act.

8 Michael Fellman, “Foreword,” in Ronald S. Coddington, Faces of the Civil War: An Album of Union Soldiers and Their Stories (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), x.

9 My emphasis. Fellman, “Foreword,” xiii.

10 Wikipedia, s.v., “Carte de Visite,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carte_de_visite, accessed October 11, 2022.

11 Fellman, “Foreword,” xi.

12 Fellman, “Foreword,” xi.

13 My emphasis. Isidora Stankovic, “Tintype Stares and Regal Airs: Civil War Portrait Photography and Soldier Memorialization,” Military Images 33, no. 4 (Autumn 2015): 55, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24864426.

14 Stankovic, “Tintype Stares and Regal Airs,” 54.

15 Stankovic, “Tintype Stares and Regal Airs,” 56.

16 John Stauffer, “Frederick Douglass, Photography, and Imagination,” in Traveling Traditions: Nineteenth-Century Cultural Concepts and Transatlantic Intellectual Networks, ed., Erik Redling (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, Inc., 2016), 115.

17 Maurice O. Wallace, “Framing the Black Soldier: Image, Uplift, and the Duplicity of Pictures,” in Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity, eds. Maurice O. Wallace and Shawn Michelle Smith (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2012), 245.

18 My emphasis. Wallace, “Framing the Black Soldier,” 246.

Works Cited

Fellman, Michael. “Foreword.” In Ronald S. Coddington, Faces of the Civil War: An Album of Union Soldiers and Their Stories, ix–xvi. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

Hoptak, John D. “Nicholas Biddle: The Civil War’s First Blood,” HISTORYNET, October 3, 2008.

Stankovic, Isidora. “Tintype Stares and Regal Airs: Civil War Portrait Photography and Soldier Memorialization.” Military Images 33, no. 4 (Autumn 2015): 53–57. .

Stauffer, John. “Frederick Douglass, Photography, and Imagination.” In Traveling Traditions:

Nineteenth-Century Cultural Concepts and Transatlantic Intellectual Networks, edited by Erik Redling, 113–137. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, Inc., 2016.

Wallace, Maurice O. “Framing the Black Soldier: Image, Uplift, and the Duplicity of Pictures.” In Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity, edited by Maurice O. Wallace and Shawn Michelle Smith, 244–266. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2012.

Wikipedia, s.v., “Carte de Visite.”

Wikipedia, s.v., “Pennsylvania First Defenders.”

Wikipedia, s.v., “United States Colored Troops.”

I have one of these original photos