The Philadelphia printer John Dunlap (1747-1812) is best known for having printed the so-called “Dunlap Broadside”—the first printing of the Declaration of Independence—of which the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library is privileged to possess two of the 26 known copies. Less well known is Dunlap’s distinction as the person responsible for bringing printing to Charlottesville, Virginia, in 1781. On the eve of July 4th, and in celebration of having acquired our very first John Dunlap Charlottesville imprint, here is the story of Dunlap’s brief career as Charlottesville’s pioneer printer.

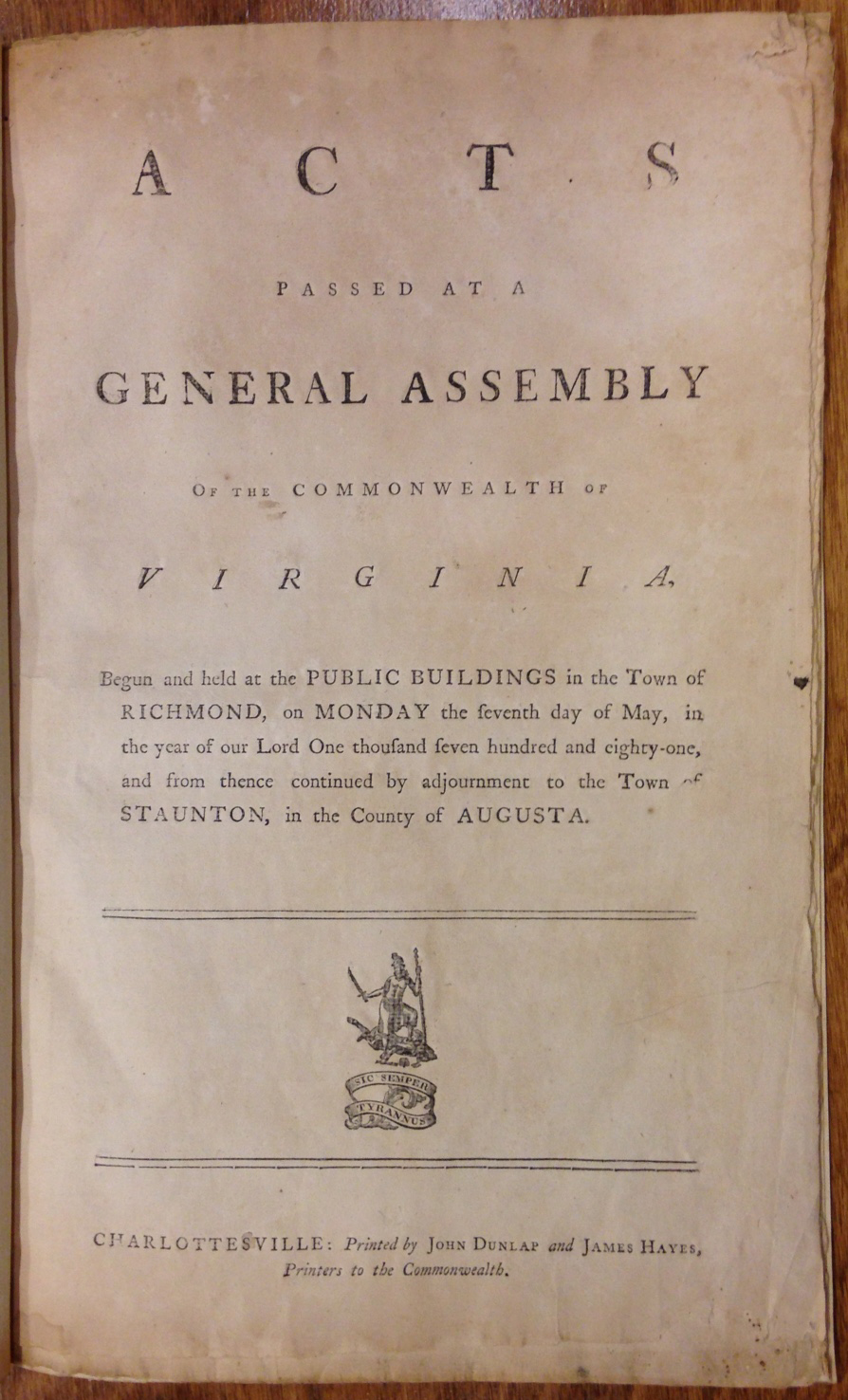

Title page of U.Va.’s newly acquired 1781 Charlottesville imprint, the first and only item from Charlottesville’s first press to have entered the U.Va. Library collections.

Eighteenth-century American printers were eager for significant business and steady cash flow, which were more easily obtained through newspaper publishing and government printing contracts than through other printing work. John Dunlap did well on both accounts. He immigrated from Ireland to Philadelphia in 1757 and, after serving an apprenticeship in his uncle’s printing establishment, took over the business. In 1771 Dunlap launched the weekly Pennsylvania Packet, or the General Advertiser. Taking advantage of his Philadelphia location and the urgent need for public printing during the American Revolution, Dunlap secured printing contracts not only for the state of Pennsylvania, but also for the Continental Congress.

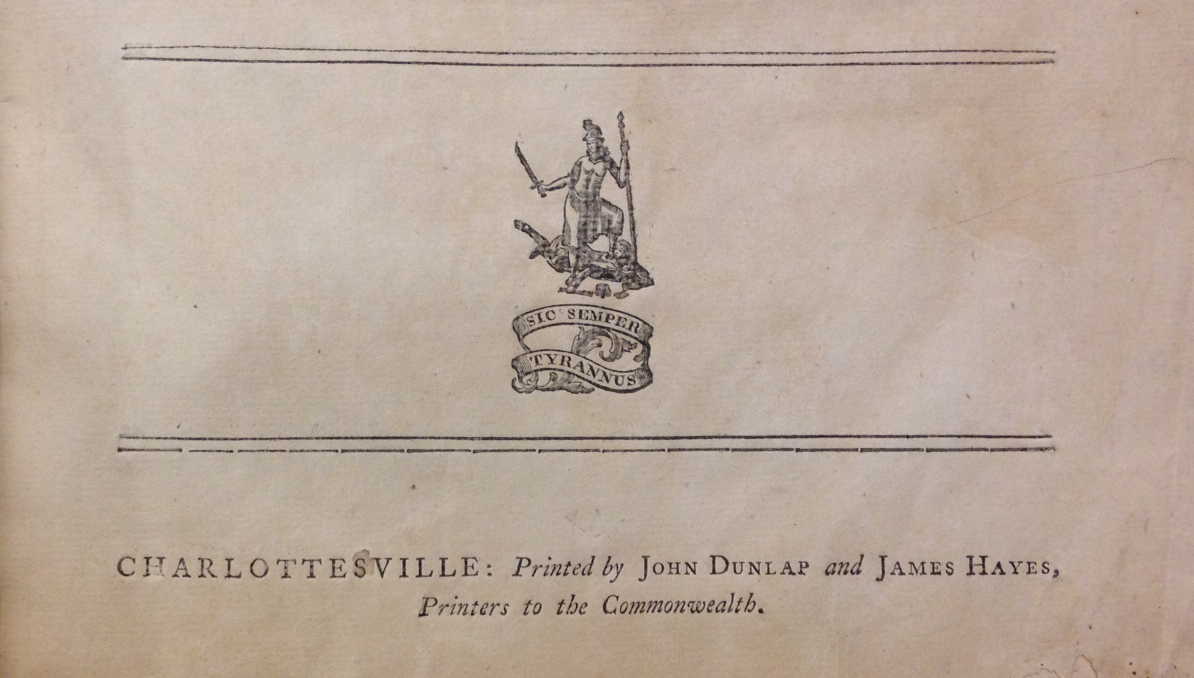

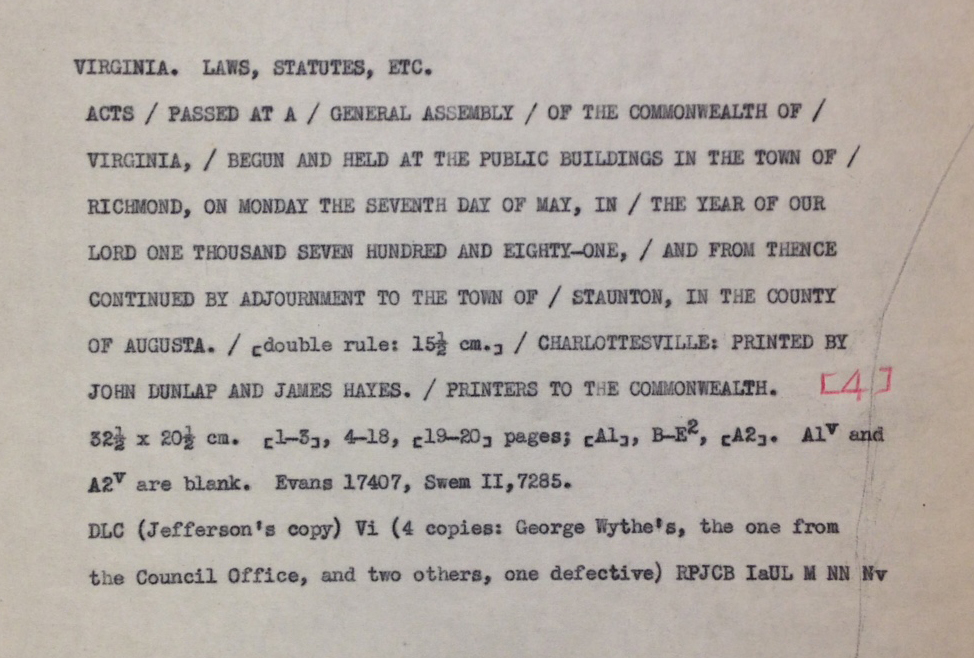

The two-line imprint crediting John Dunlap and James Hayes as Charlottesville’s first printers. Although undated, this work was printed during September and October of 1781.

In August of 1780, Dunlap expanded his public printing portfolio to Virginia. Directed by Virginia’s House of Delegates to engage a public printer, then-Governor Thomas Jefferson recommended acceptance of the proposal submitted by Dunlap and his business partner (and former apprentice) James Hayes. That fall a press and supply of printing types was dispatched to Richmond, where Hayes was to establish and manage a printing office. But its opening was delayed when the shipment fell into British hands. A second press was sent from Philadelphia to Richmond, and Hayes was at long last able to begin printing in April 1781.

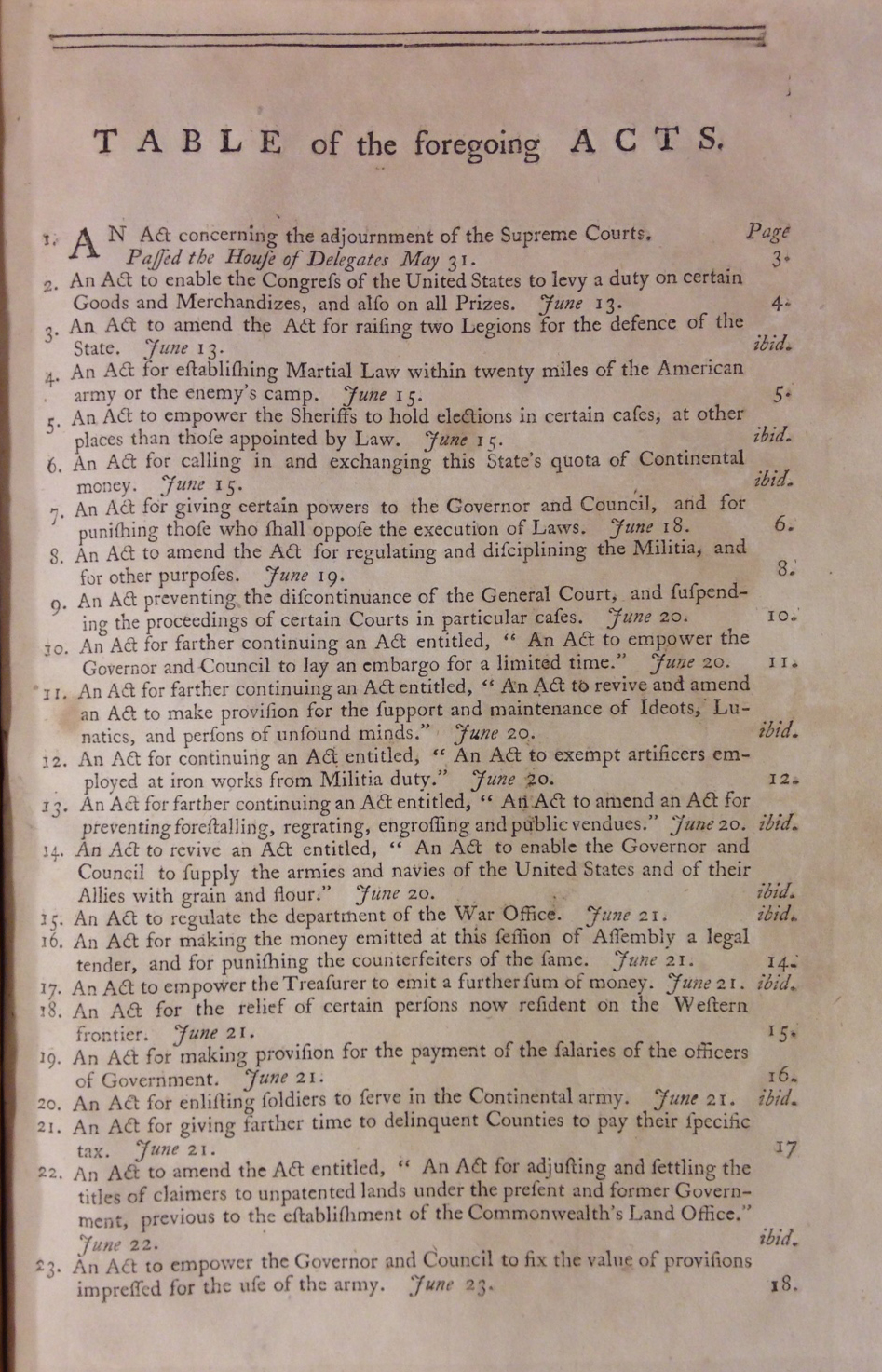

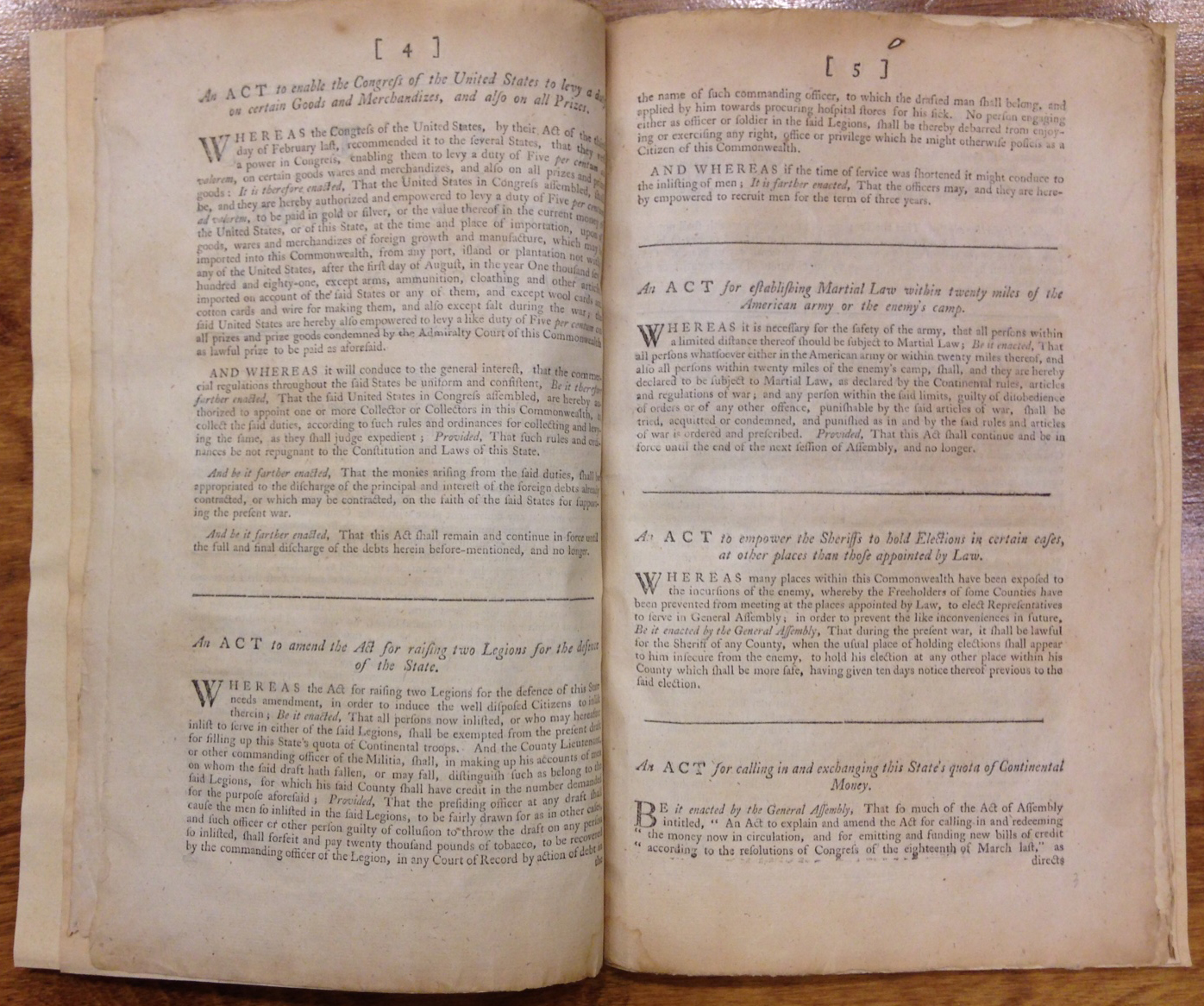

A two-page opening from the Acts Passed at a General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia (Charlottesville, 1781).

The following month, however, the arrival of British forces under General Cornwallis prompted Virginia’s state government to flee Richmond, first to Charlottesville, and then to Staunton. Hayes packed up his printing equipment and followed. But in late June, near Charlottesville on his way back from Staunton, Hayes was captured by the British and then released on condition that he not print “until properly exchanged.” This was soon arranged, and in July 1781 Hayes set up his press in Charlottesville. It remained in operation into October, but by early December Hayes had relocated the press to Richmond. All the while Dunlap remained in Philadelphia.

In its three months of operation, the first Charlottesville press is known to have printed at least four items: two broadsides, the 52-page Journal of the House of Delegates of Virginia for 1781, and the 1781 Virginia session laws. It is a copy of this last publication—a 20-page folio publication titled Acts Passed at a General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia—that has now been acquired by U.Va. Given the constraints under which Hayes is known to have operated, it is tolerably well printed, bearing the Virginia seal on its title page above the two-line imprint: CHARLOTTESVILLE: Printed by John Dunlap and James Hayes, Printers to the Commonwealth.

John Cook Wyllie’s bibliographical description of the 1781 Virginia session laws (Charlottesville, 1781) with (at bottom) a census of copies known ca. 1960.

All four known 1781 Charlottesville imprints were printed by Hayes in his role as public printer, and all are very rare. It is likely, however, that Hayes printed a few other items, e.g., broadsides, printed forms, and other jobbing work, during his Charlottesville sojourn. Some day we may be able to identify these through careful typographical analysis. The history of Charlottesville’s first press has yet to be written–this précis is based on unpublished research by former U.Va. Librarian John Cook Wyllie, which is available for consultation in the Small Special Collections Library.

Following Hayes’ departure, Charlottesville would remain without a printing press for another four decades, until Clement P. and J.H. McKennie established a newspaper, The Central Gazette, in 1820.