This week we are pleased to feature a post by graduate student Kelly Fleming. Kelly is a Ph.D. candidate in English and a curatorial assistant in Special Collections. She writes for us here about her first solo exhibition.

The word “feminist” is lit up in bright lights these days, and not just thanks to Beyoncé. Celebrities use their place in the spotlight to complain about the gender wage gap. Young women wear t-shirts with a crowned Ruth Bader Ginsburg, emblazoned with the words “Notorious RBG.” Students, unprompted, use the word “intersectional” in my classroom, deploying a piece of feminist terminology that was coined the year I was born.

Fifty years ago, in 1966, when Betty Friedan and other feminists formed the National Organization of Women (NOW), their statement of purpose declared, “The purpose of NOW is to take action to bring women into full participation in the mainstream of American society now, exercising all the privileges and responsibilities thereof in truly equal partnership with men.” While we still need to work toward a “truly equal partnership” in this country, feminism has become mainstream. In fact, it has hit mainstream society with such force and such flare that there is debate about the rise of a new wave, as well as new names: “pop feminism” and “marketplace feminism.” At least in part, we are living out Friedan’s dream in this very moment.

Yet in this moment, we are at risk of forgetting the women who wore the word “feminist” like a medal of honor into battle. Perhaps because they did not want to be part of “mainstream” American society, the achievements and work of radical feminists are the most often forgotten. “Sisters of the Press: Radical Feminist Literature, 1967–1977” is an attempt to shed light on this particular history of feminism.

Radical feminists took the second-wave feminist mantra—the personal is political— and made it into a lifestyle. Because they believed that American society was underpinned by a patriarchal system stretching back centuries, they sought to destroy its institutions, hierarchies, and beliefs. To work within the system was to be complicit in the oppression of all American women by men, a fact that the “mainstream” feminist movement, epitomized by NOW, would not formally acknowledge. As a result of this conviction, radical feminists did more than just join consciousness-raising groups. They formed collectives, they lived in non-hierarchical all-female communities, and they dispensed plastic speculums for personal use. But more than anything else, they wrote. They penned scathing critiques in easily disseminated materials, such as manifestos, periodicals, pamphlets, petitions, and flyers, that circulated to sisters nationwide and that provided the basis for radical action.

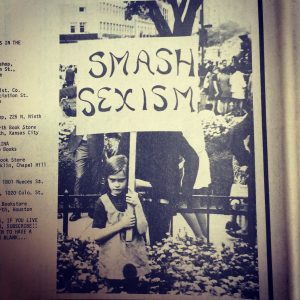

Detail from the February/March 1973 issue of the radical feminist periodical, Off Our Backs. (HQ1101. O34 v.3 no.6)

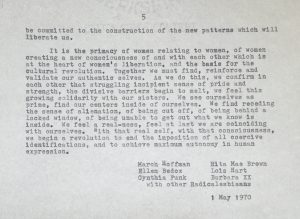

While these radical feminists texts may not be as famous as Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (1949), or Betty Friedan’s The Feminist Mystique (1963), their clear, concise messages still inspire change today. I am not alone in having read the Radicalesbian’s essay, “Woman-Identified Woman,” during my undergraduate studies, and imagine my excitement (which was effusive), when I found that we had Rita Mae Brown’s personal copy, complete with editorial marks, in the archives.

Shown here is last page of the essay, with the signatures of co-founder Rita Mae Brown and other members of the Radicalesbians. (MSS 12019)

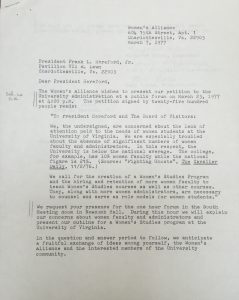

Another item in the exhibition that I know has impacted women today, and women at UVA in particular, is a letter from a feminist group called the Women’s Alliance. UVA did not admit female undergraduates until 1970 and only did so then because it was court mandated. In response to the “traditional sex stereotyping” female students continued to see in UVA classrooms, the Women’s Alliance demanded in 1977 that the university hire more female faculty members and create a women studies’ program. Even though radical feminists wanted to tear down institutions, their arguments did transform one institution, the university, from within. The UVA Women’s Center and the Women, Gender & Sexuality Program are the result of their efforts.

The letter the Women’s Alliance sent to UVA President Hereford, regarding their petition for a women studies program, which reached nearly 3,000 signatures. (RG-2/1/2.791)

“Sisters of the Press” may not be as powerful as Beyoncé standing in front of the word “feminist” at her concert, but it will remind of us of the women who were feminist before it was cool.

“Sisters of the Press” is on view through August 31st in the First Floor Gallery of the Harrison/Small Building. Come take a look!

Ms. Fleming,

Belatedly saw your posting and wanted to call something to your attention that you might find amusing (or maybe appalling). In November, 1953, the Virginia Spectator published a “Co-ed Go Home Issue,” with all sorts of sexist poems and cartoons. It was pretty funny at the time, maybe not so much now. Anyway, you ought to take a look at it. I’m sure it’s in the files there. I’ve still got my copy.

Incidentally, I knew Michael McWhinney and he was a good guy. Really.

Randy Pendleton