The teletype printout of the UPI broadcast wire from Jacksonville, Florida, from just before the first report of Kennedy’s shooting to the end of the day. (MSS 15678, Gift of Randolph Pendleton. Photo by Molly Schwartzburg)

Special Collections recently received an unusual–and remarkable–gift: a roll of paper, over forty feet long, which plunges its reader into the hours following John F. Kennedy’s assassination. It is a teletype machine printout of wire reports received by the United Press International bureau in Jacksonville, Florida, following the shooting, from which local radio stations–and others across the nation–communicated the news to rapt regional audiences.

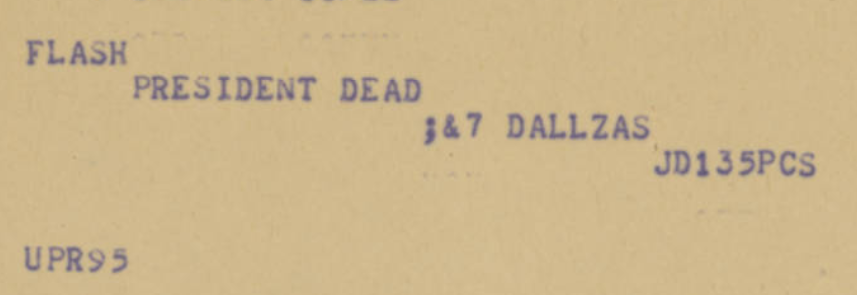

This section of the scroll reveals the moment at which radio-station employees learned that Kennedy had not survived. (Image by U.Va. Library Digitization Services)

The printout was rescued for posterity on November 22, 1963, by UPI’s Jacksonville bureau manager Randolph Pendleton, who now lives in Charlottesville. Mr. Pendleton has kept the printout all these years. With the anniversary drawing near, he decided to donate it to Special Collections so it could be seen by all who are interested. We were thrilled to oblige. The library’s Digital Curation Services division rushed to produce a high-resolution digital facsimile of the entire scroll, which is now available to read in full. This Friday, on the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination, you can follow the broadcasts in real time on twitter at @uvadigserv.

Mr. Pendleton contributed a summary of the broadcast’s transmission:

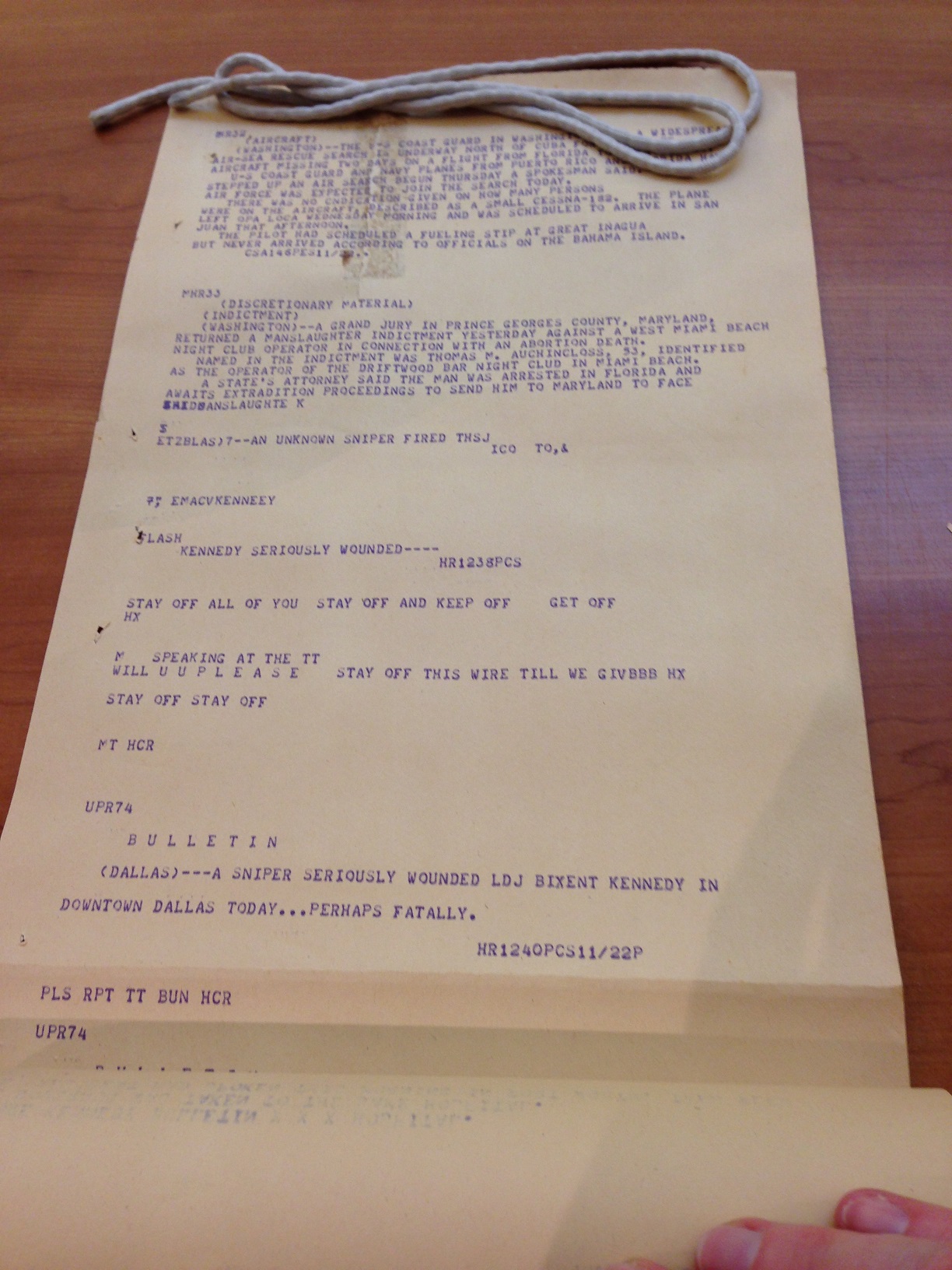

“The broadcast wire, designated 7551 and usually referred to as the radio wire, went to hundreds of radio and television stations across the United States. It was rewritten in broadcast style from the A-wire, which was the main newspaper wire, and thus ran a few seconds behind. It was filed by the Chicago bureau, (call letters HX) and was split for twenty minutes every hour on the half-hour so that local bureaus could file state and local copy. Because this was a teletype in Florida, it was running Florida stories filed by the Miami bureau (call letters MH) when Chicago broke in to reclaim the wire and file the flash, a rarely used priority that is accompanied by ten bells. The Chicago bureau then sought to keep the wire clear by warning bureaus to stay off. This flash was the first word of the shooting that broadcast stations across the country received.

The first news of the shooting appeared in flashes, whose text was sometimes garbled due to the efforts of multiple bureaus to file at once. (Image by Molly Schwartzburg)

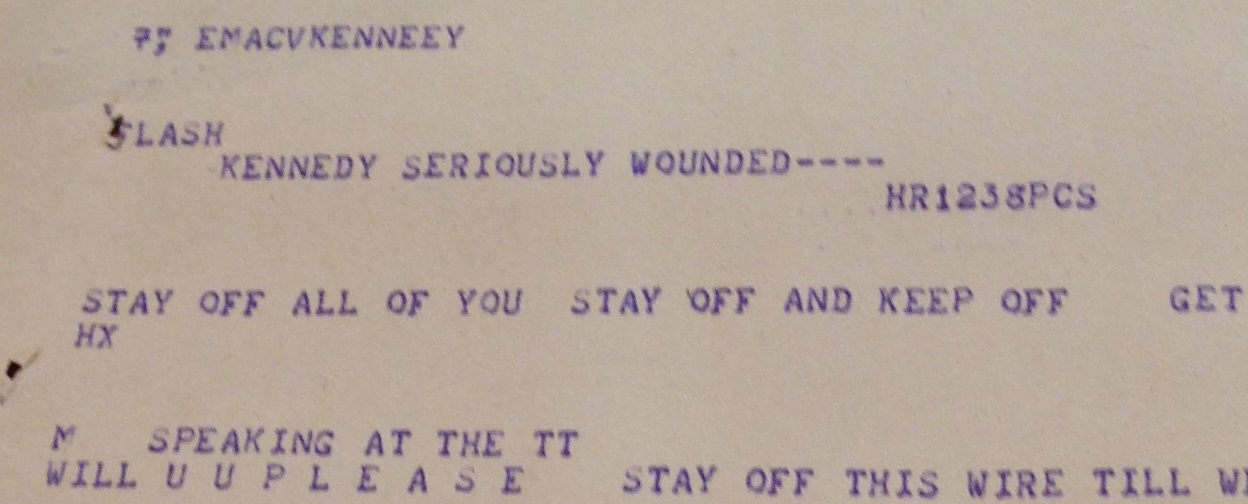

Repeated requests from the Chicago bureau for clear lines, in the first moments of the news breaking. (Image by Molly Schwartzburg)

“The reporting came from Merriman Smith, the UPI White House reporter and dean of the White House press corps, who was in the front seat of the wire service pool car, riding six cars behind the president’s convertible. He grabbed the car’s phone when he heard three shots and began dictating to the Dallas bureau, fending off attempts by Associated Press reporter Jack Bell to get the phone away from him. On arrival at Parkland Hospital, Smith (who won the Pulitzer Prize for his coverage) was able to grab a Secret Service agent and get confirmation that Kennedy was seriously wounded and then find another phone amid the chaos in the hospital to call in the flash. The bulletin filed from the pool car had said only that three shots had been fired at the motorcade. This ran on the A-wire but came through garbled on the first broadcast wire because Chicago had trouble getting some of the state bureaus to stop filing. The first bulletin after the flash was also garbled and the Los Angeles bureau, (call letters HC) asked for a repeat.

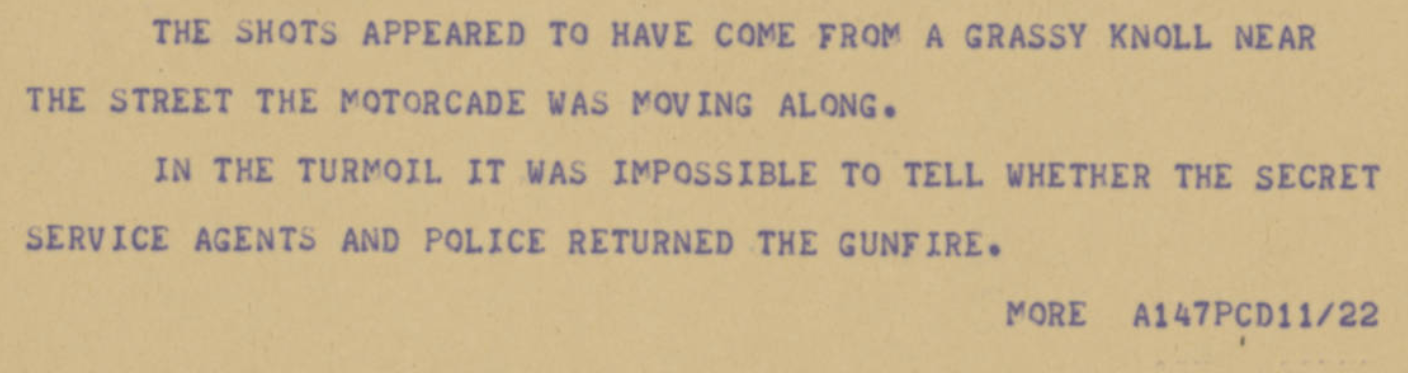

“After that, the story unfolded quickly and within minutes there was a reference to the famous ‘grassy knoll.'”

The broadcast wire’s first use of the phrase “grassy knoll.” Time stamps at the end of each posting are Central Standard, because the wire was being filed from Chicago. (Image by U.Va. Digitization Services)

Thanks to Mr. Pendleton for his generous donation and summary. And thanks also to Digitial Curation Services for the magnificent digital facsimile, which will allow many readers to experience this unique artifact.

We encourage readers to share their memories–particularly if they heard the news on the radio. For more background on the Chicago bureau’s role in the day’s events, see this recent article in the Chicago Sun Times.

My late husband was working at a radio station in SC and I have an original copy of this Bulletin. Do you know of anyone who might have an interest in this?

I also have another Bulletin about Racism and Riots.

Sincerely,

Cathryn Lennon

FLASH(done in all caps) The scariest word to come over the wire. When you get one something VERY VERY bad has more than lily happened or something that is historic it needs the highest level. And it always tersely worded