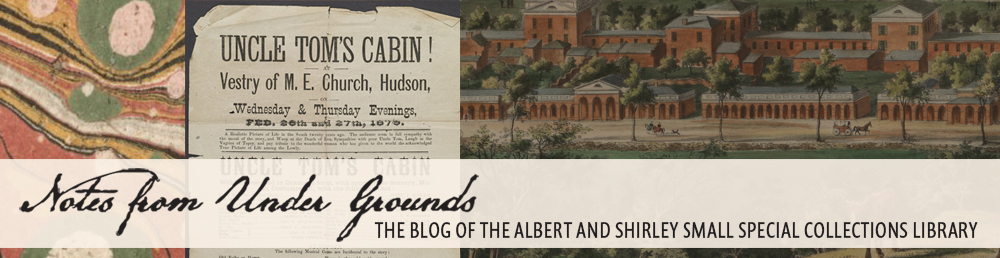

We are back with fore-edge paintings, Margaret Fuller, and that infamous word that starts with the letter:

F is for Fancy Roman, which is one of 75 alphabets represented in Frank H. Atkinson’s Atkinson Sign Painting up to Now: A Complete Manual of Sign Painting. Chicago: Frederick J. Drake & Co., 1915 (not yet catalogued. Gift of Nicholas Curtis. (Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

F is for the “F” word

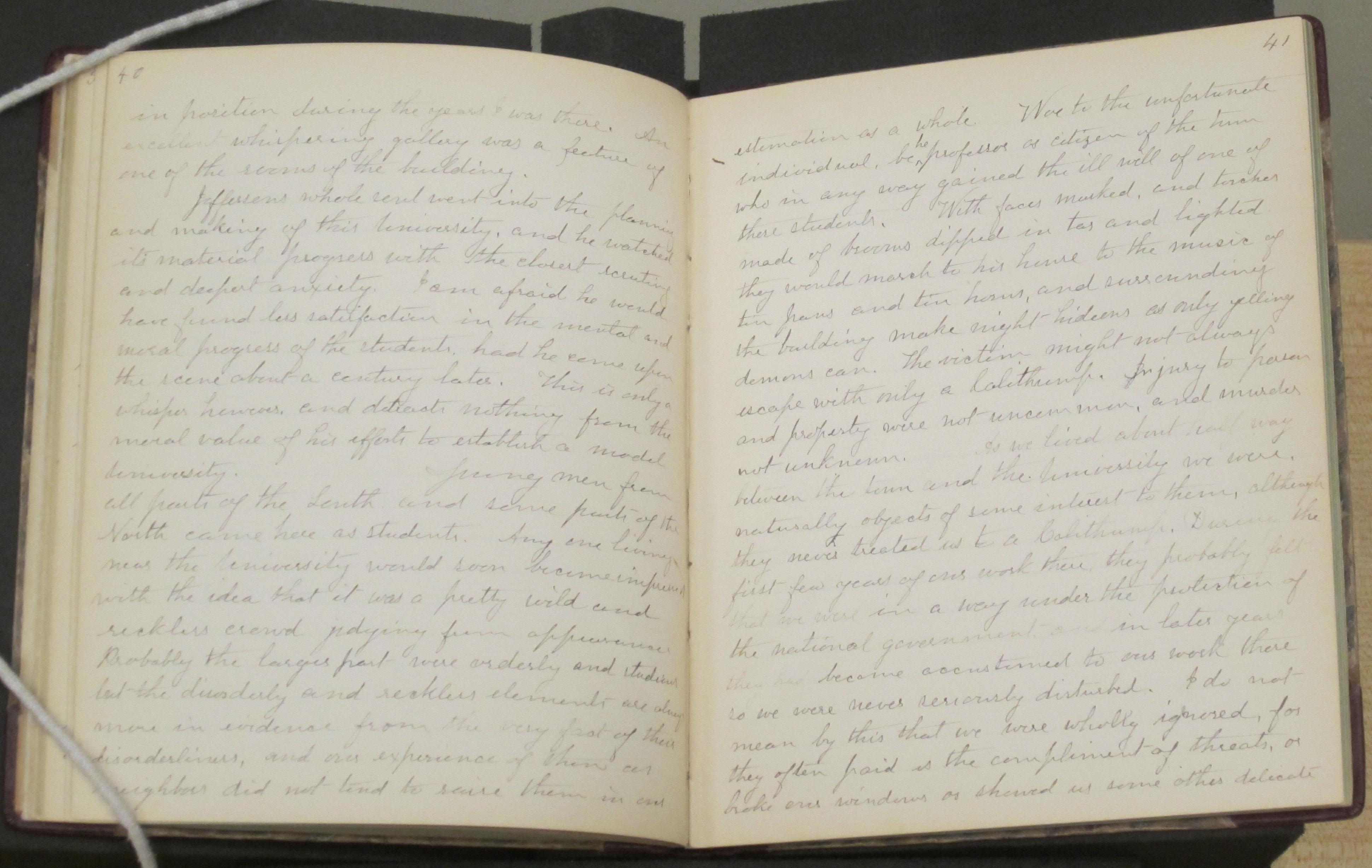

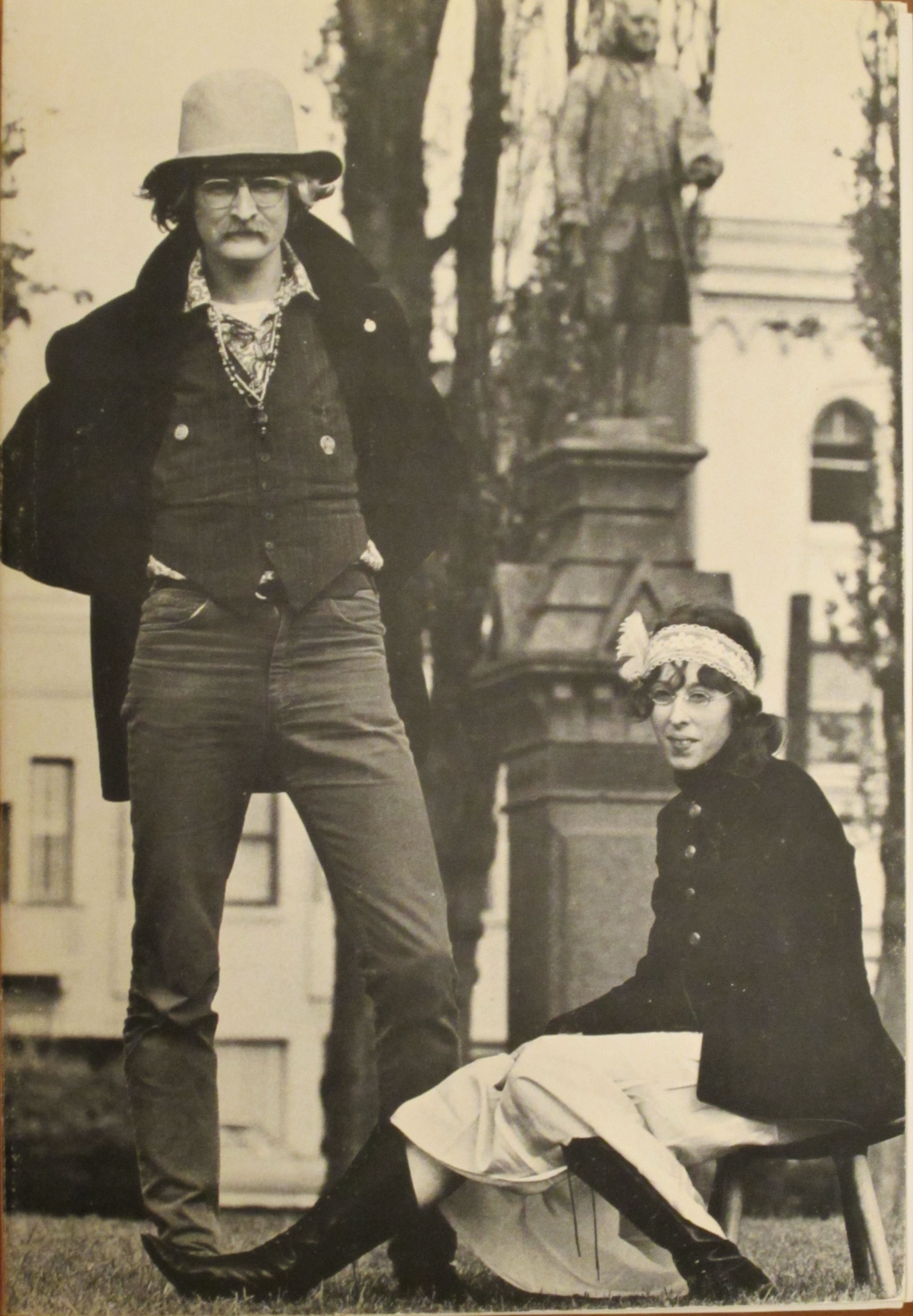

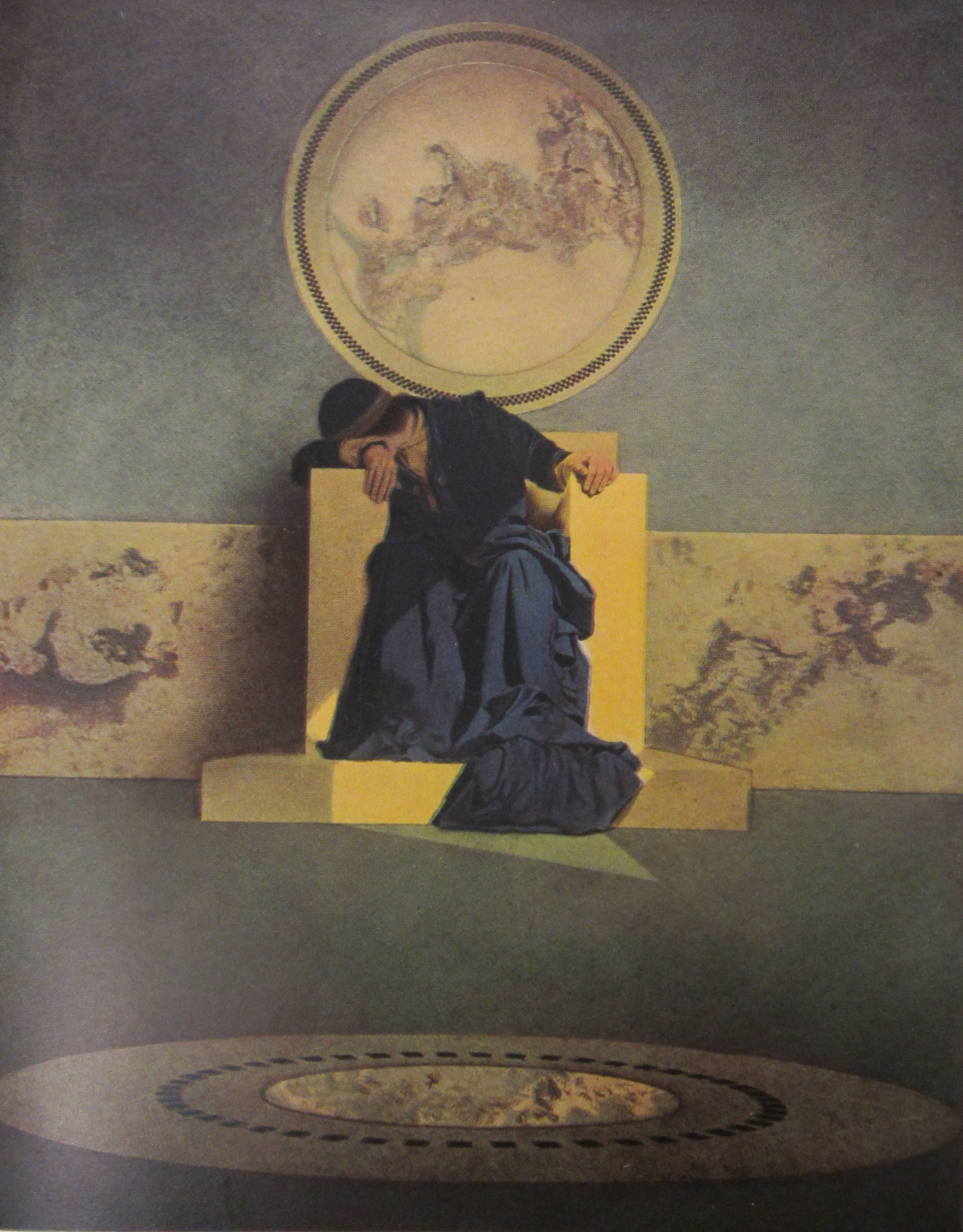

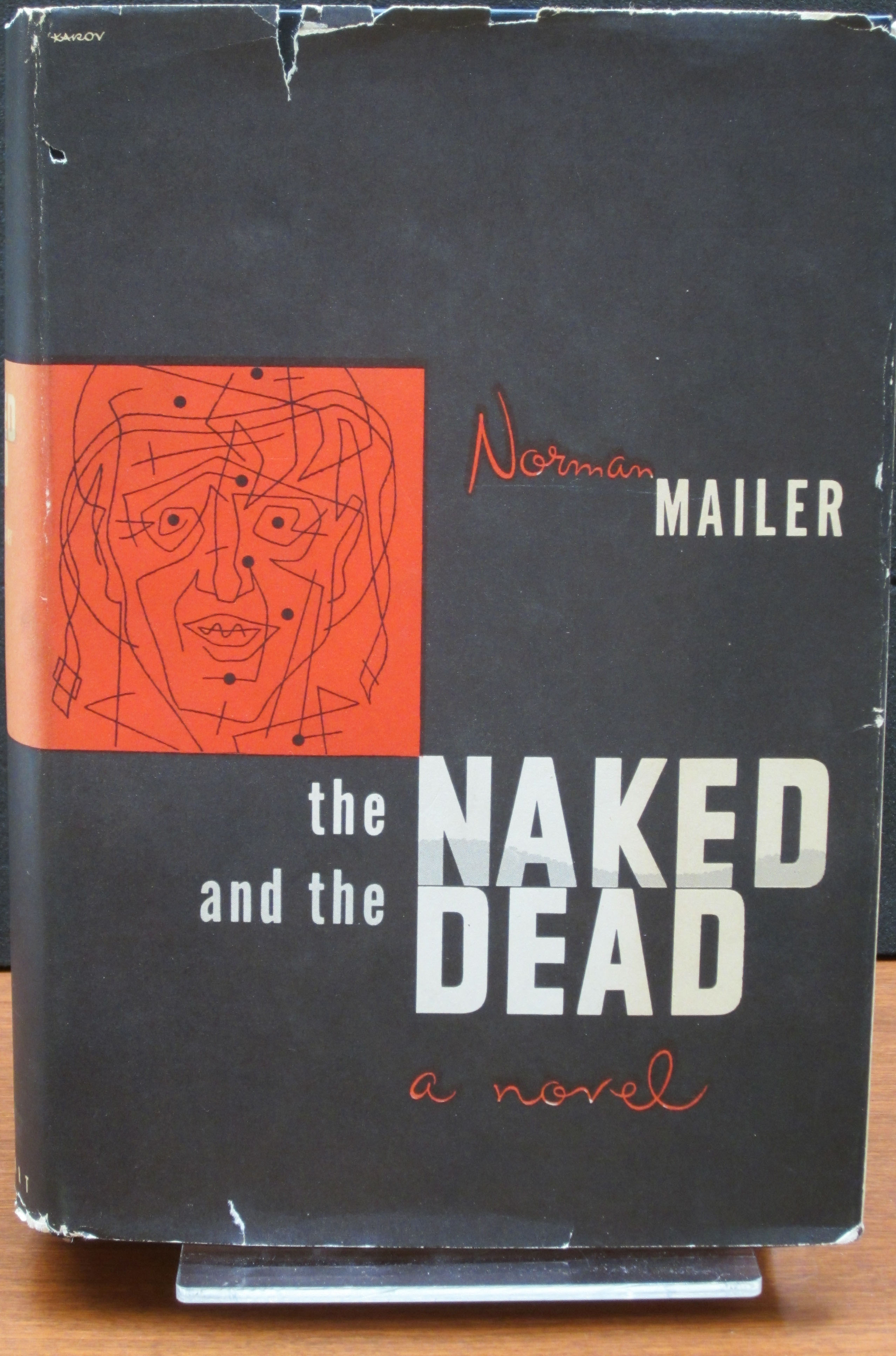

Widely considered the most offensive word in English, f*** has been a part of the language since at least the 15th-century and remained virtually unprintable until the late 20th-century. Norman Mailer famously created the euphemism “fug” in The Naked and the Dead and was subsequently teased as “the young man who doesn’t know how to spell ‘f**k.’” By the 1960s, the taboos against it were relaxing and the counterculture used it enthusiastically in poems, magazines, and even naming a publishing operation The F*** You Press.

Contributed by Edward Gaynor, Head of Description and Specialist for Virginiana and University Archives

Cover of Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead, 1948. The jacket design is by Karov. (PS 3525 .A4152 N3. Photograph by Petrina Jackson.)

Front and back covers of Fuck You: A Magazine for the Arts, number 4 (Aug. 1962) and number 5, volume 5 (Dec. 1963), respectively. The magazine was published, printed, and edited by Ed Sanders. (AP2 .F96. Marvin Tatum Collection of Contemporary Prose and Poetry. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

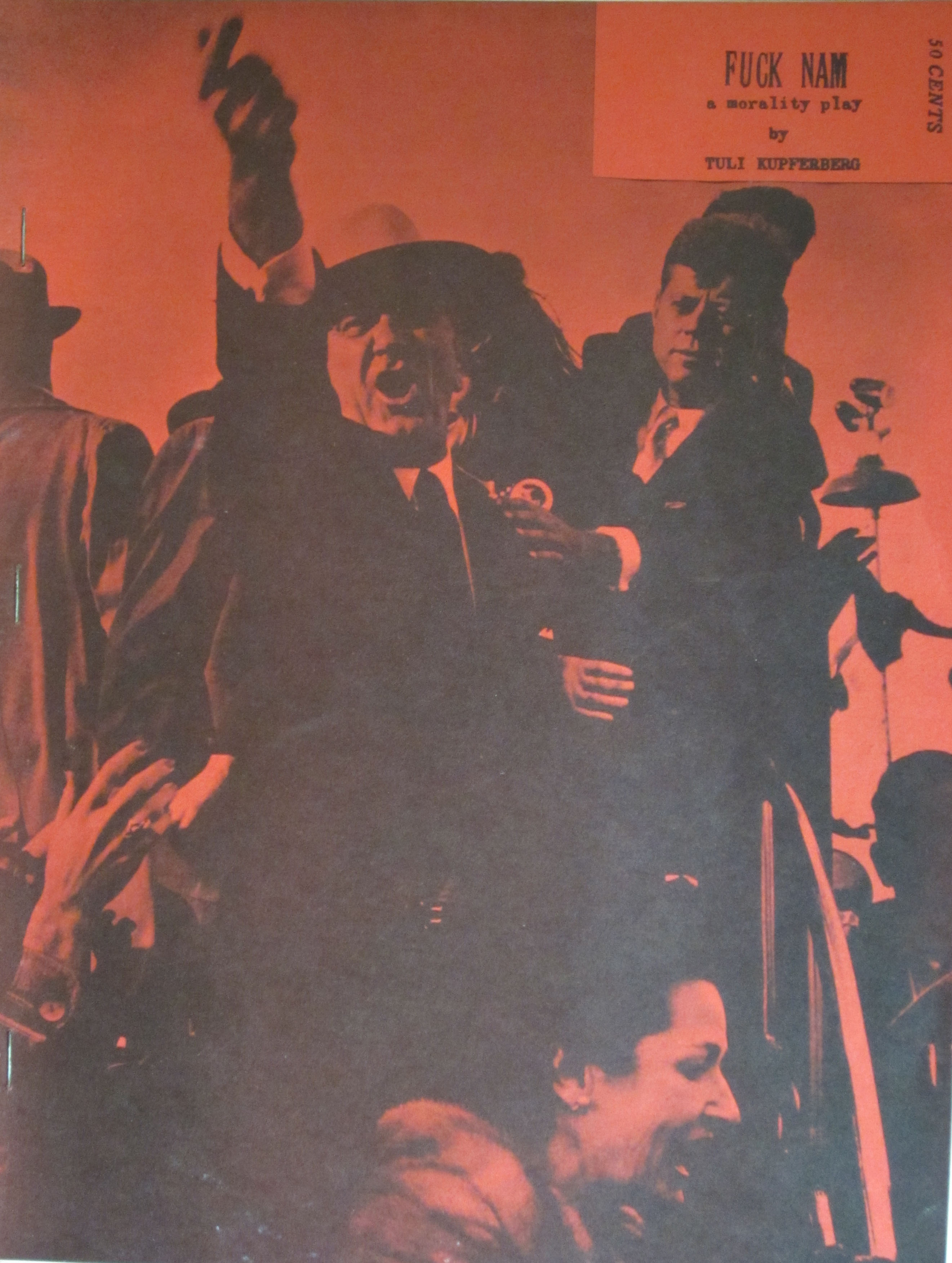

Cover of Fuck Nam: A Morality Play by Tuli Kupferberg, 1967. (PS3561 .U63 F8 1967. The Marvin Tatum Collection of Contemporary Prose and Poetry. Photograph by Petrina Jackson).

F is for Fore-Edge Painting

You can’t judge a book by its cover. You may, however, judge it by its fore-edge painting. The Merriam Webster dictionary defines fore-edge painting as “the method or act of painting a picture on the fore edge [or the front outer edge of a book] so that the picture is visible only when the pages are slightly fanned.” This method of enhancing the edges of books with paintings has wowed bibliophiles as far back as the 10th-century.

Contributed by Regina Rush, Reference Coordinator

Fore-edge of Thoughts on Hunting: in a Series of Familiar Letters to a Friend. (SK 285 .B39. 1820. Bequeathed to the School of Medicine of the University of Virginia by the Moyston Estate. Placed on indefinite loan in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

This is the first image of a double fore-edge painting from Thoughts on Hunting: in a Series of Familiar Letters to a Friend. (SK 285 .B39. 1820. Bequeathed to the School of Medicine of the University of Virginia by the Moyston Estate. Placed on indefinite loan in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

This is the second image from the double fore-edge painting from Thoughts on Hunting, which can be seen by fanning the text block the opposite way of the first image. (SK 285 .B39. 1820. Bequeathed to the School of Medicine of the University of Virginia by the Moyston Estate. Placed on indefinite loan in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

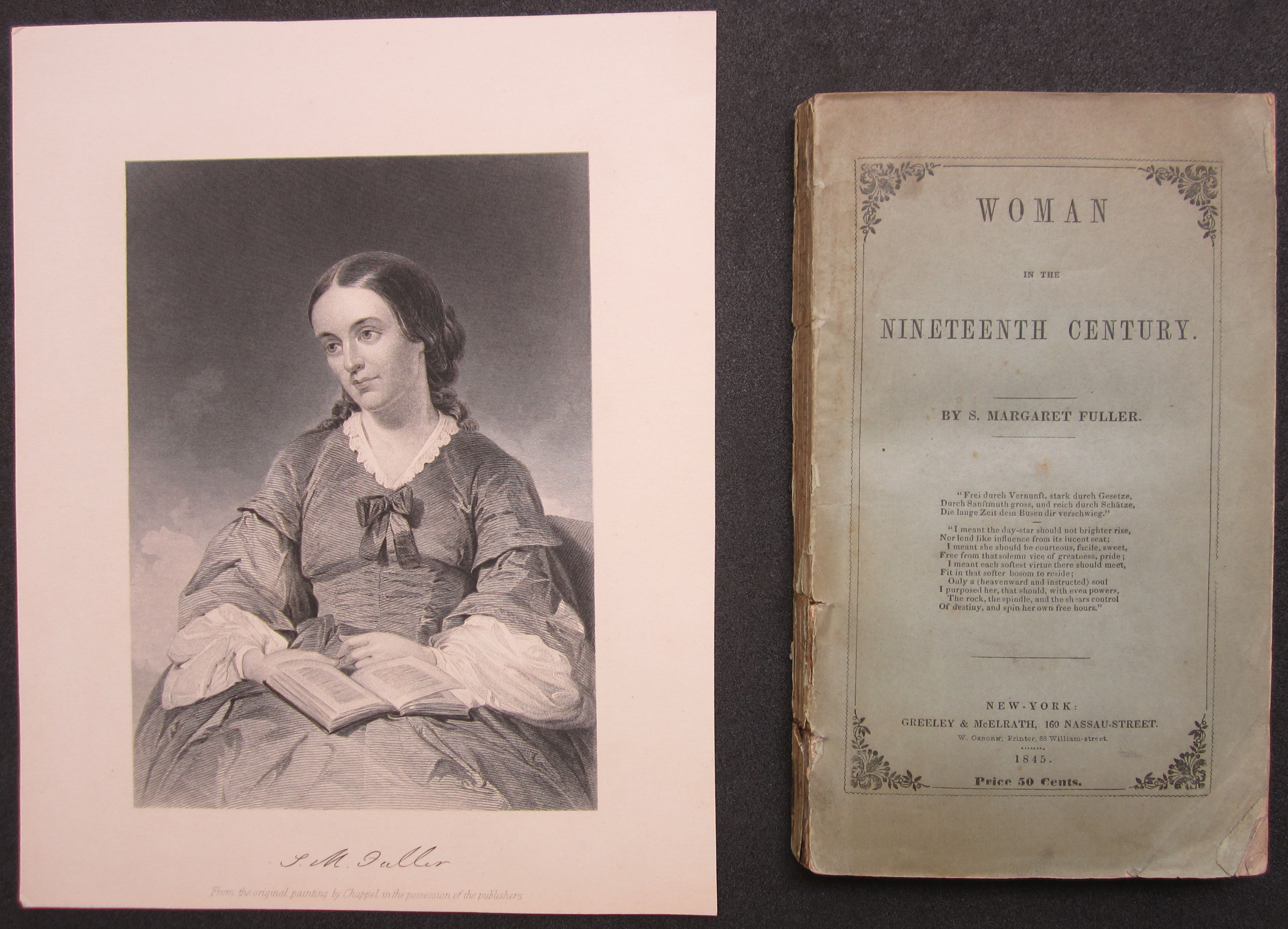

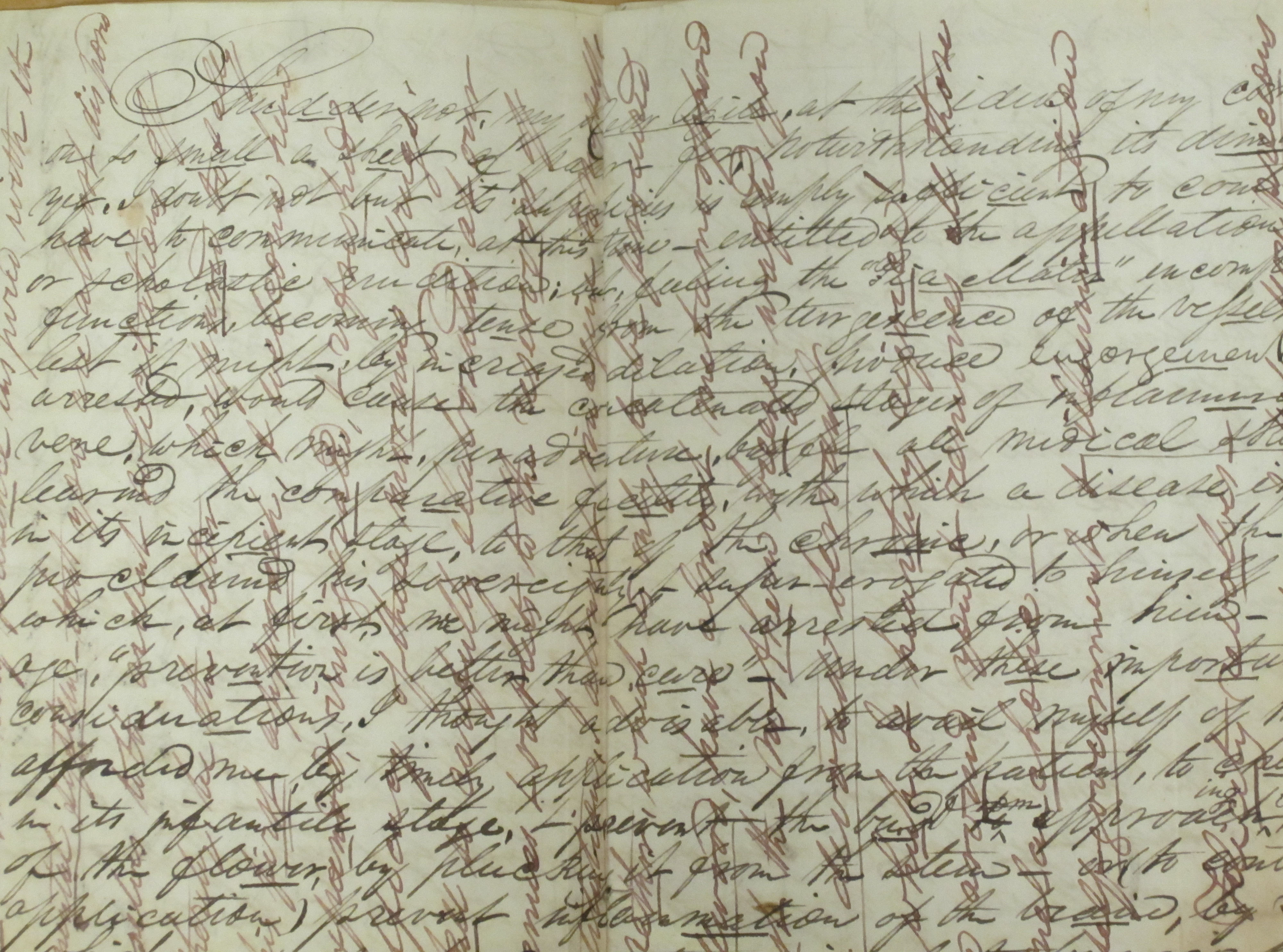

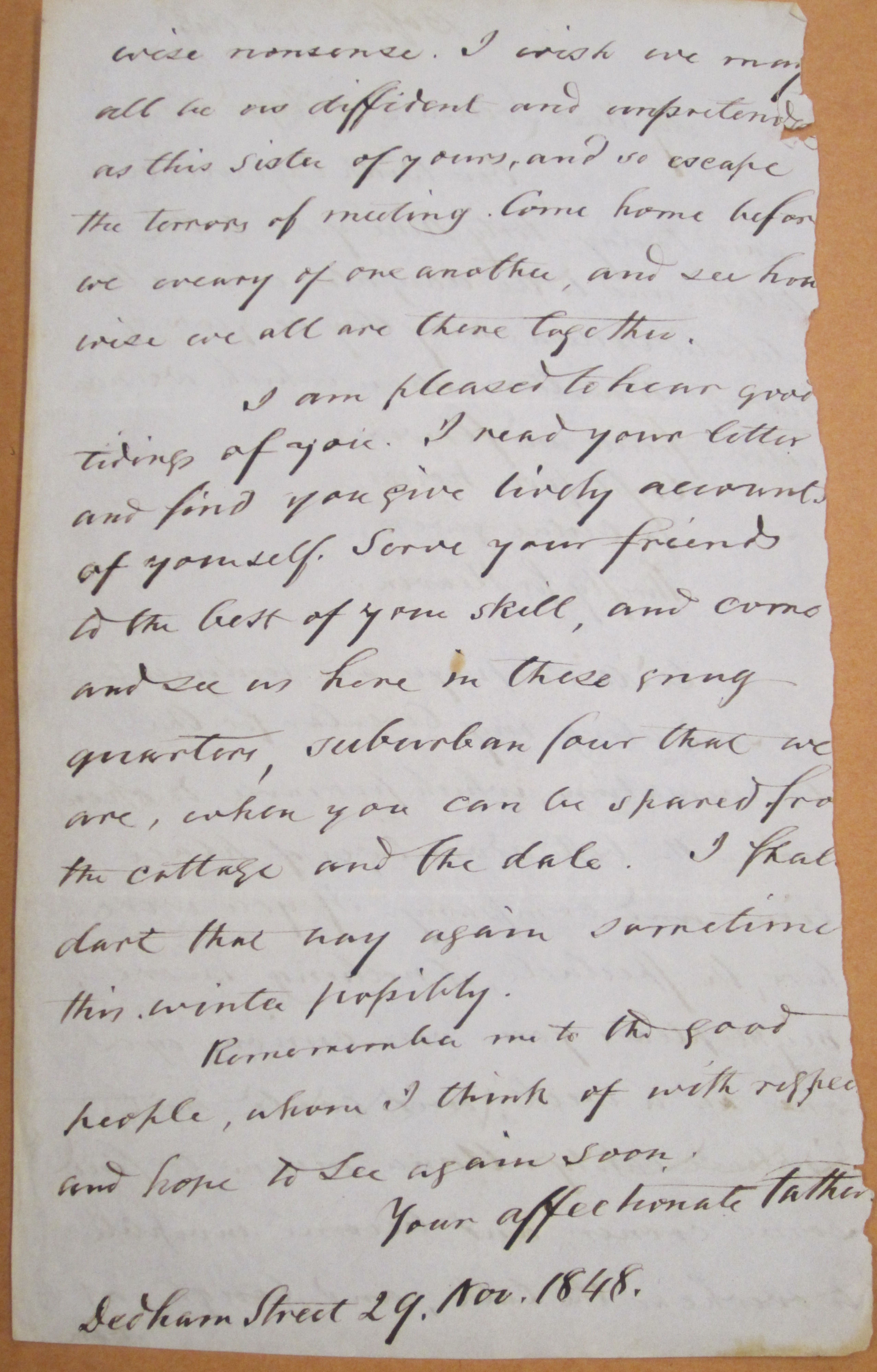

F is for Margaret Fuller

One of the most prominent members of the Transcendentalist Movement, Margaret Fuller embraced reform in the 19th-century as a tireless promoter for women’s rights, the abolition of slavery, as well as for education and prison reform. She was editor of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s journal, The Dial during its first two years of existence, and her book, Woman in the Nineteenth Century, was a groundbreaking work promoting a woman’s right to education and employment. A search of Virgo shows 21 records relating to Margaret Fuller, including printed and manuscript material.

Contributed by George Riser, Collections and Instruction Assistant