This week, we are pleased to feature a guest post by Cori Field of the Women, Gender & Sexuality Program. Cori is an exceptional colleague who really “gets” what an exhibition can do for her students. We are so lucky to have worked with her on the exhibition described below.

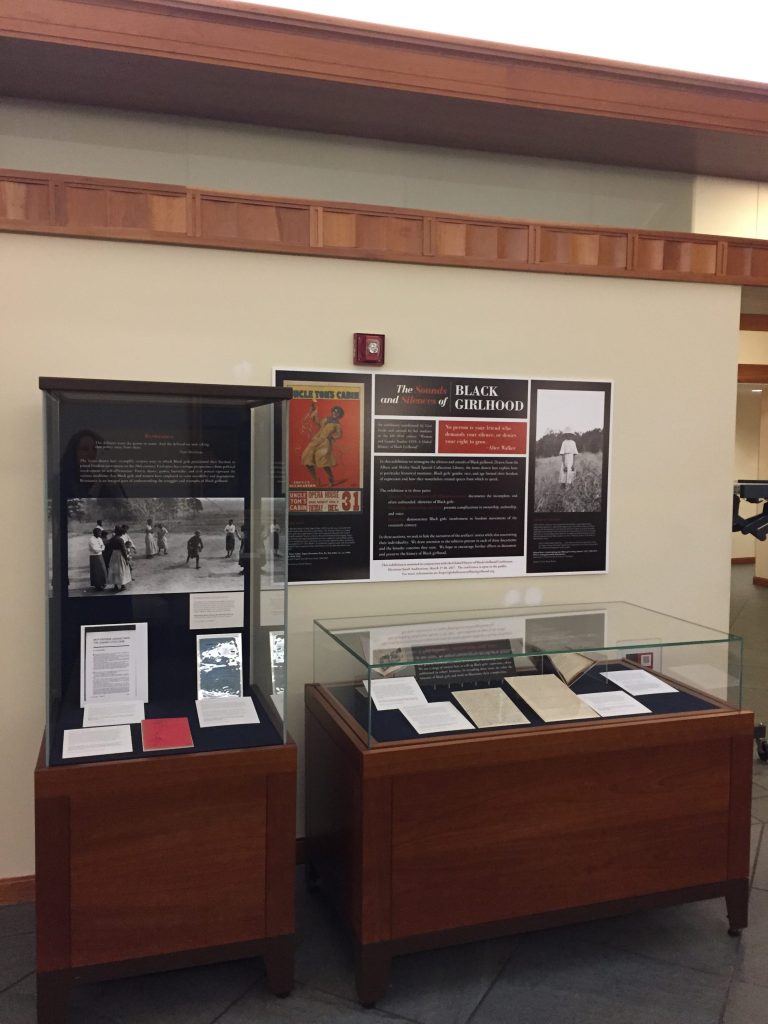

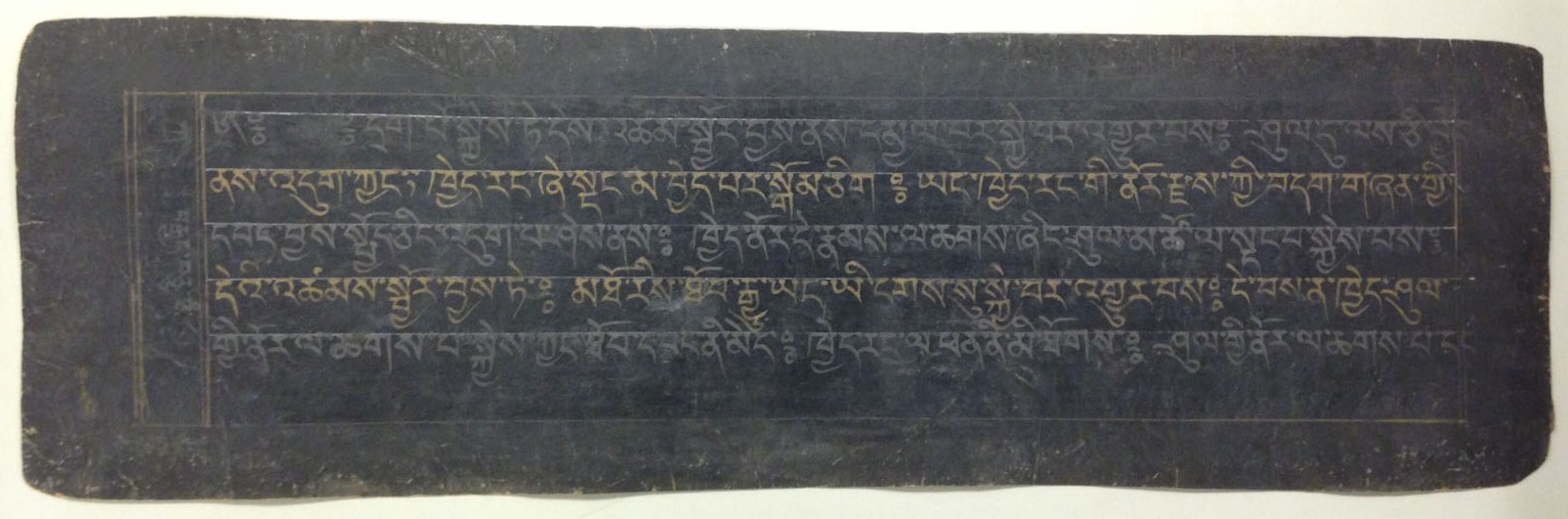

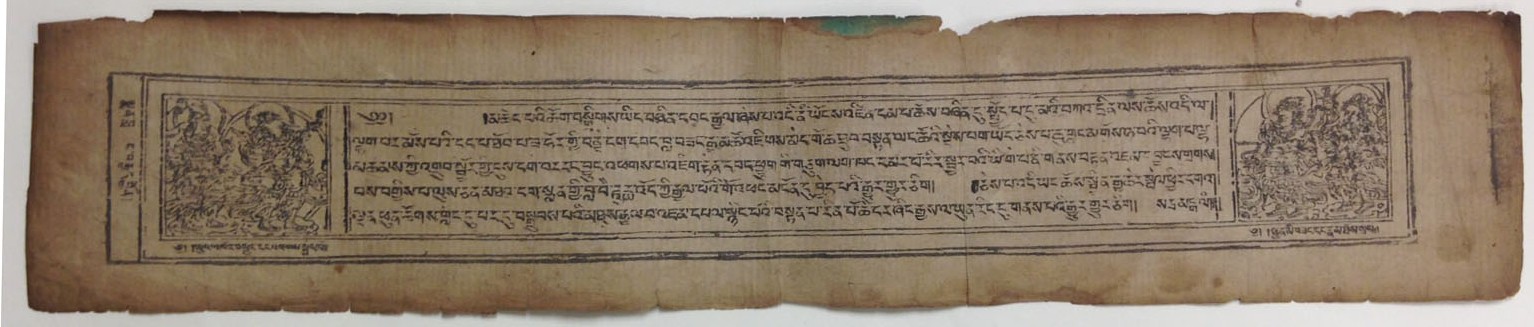

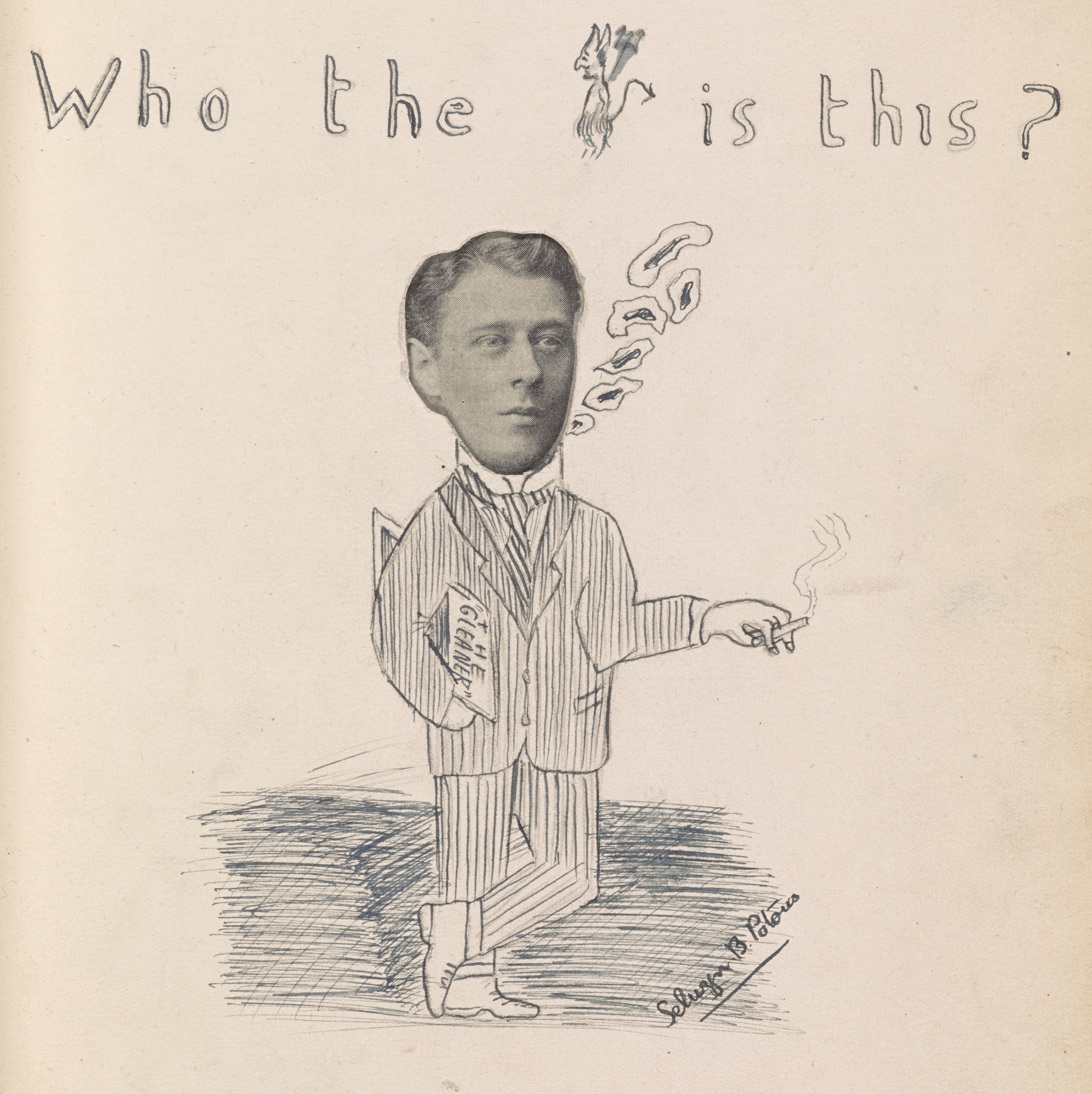

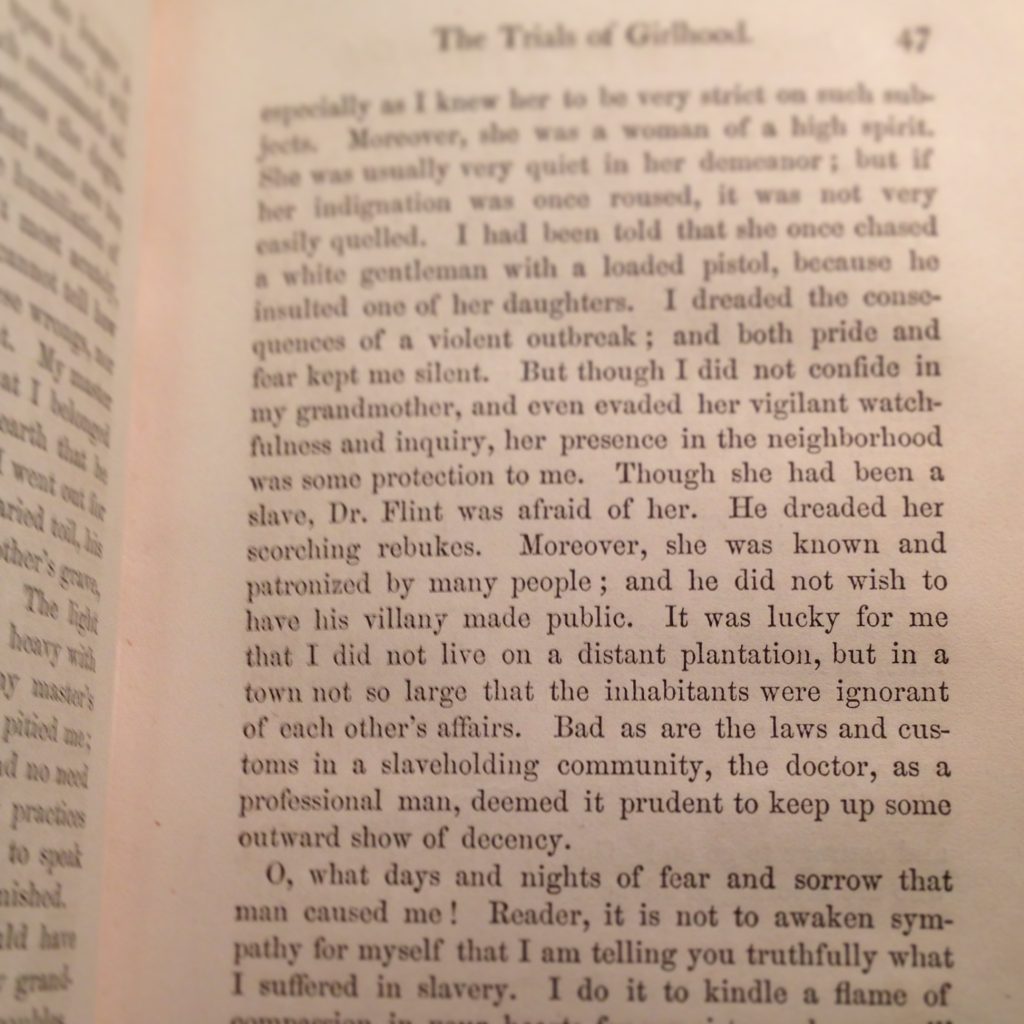

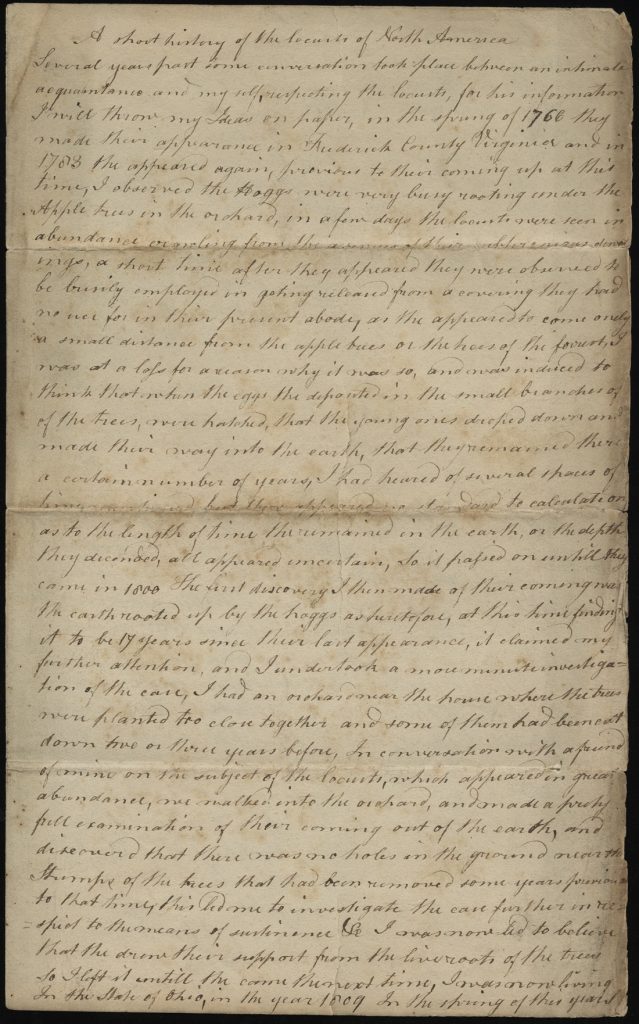

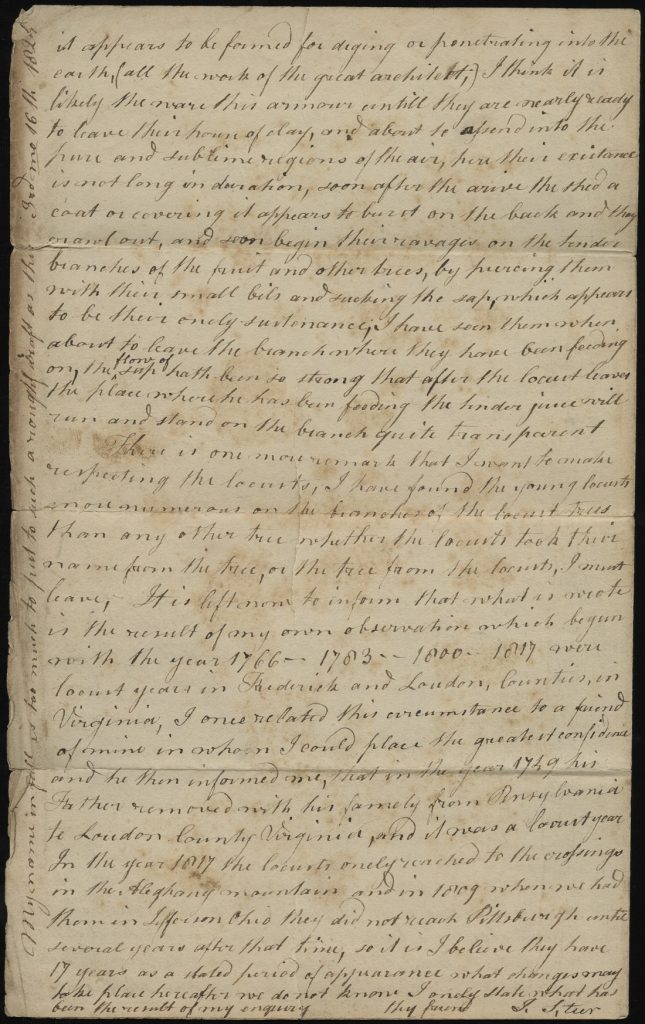

The “Sounds and Silences of Black Girlhood” exhibition resulted from a remarkable collaboration between undergraduates in the Women, Gender & Sexuality Program and Library staff. Finding archival sources by and about black girls is difficult even for professional historians because most collections are organized around the concerns of white adults. Undaunted, UVA students eagerly stepped up to the challenge. With the help of Molly Schwartzburg, Holly Robertson, and Erin Pappas, they identified a wide range of materials in Special Collections related to the global history of black girlhood, researched the significance of those items, and designed a compelling exhibit focused around the core themes of identity, resistance, and voice. In addition to curating the exhibit, they wrote longer articles about each item.

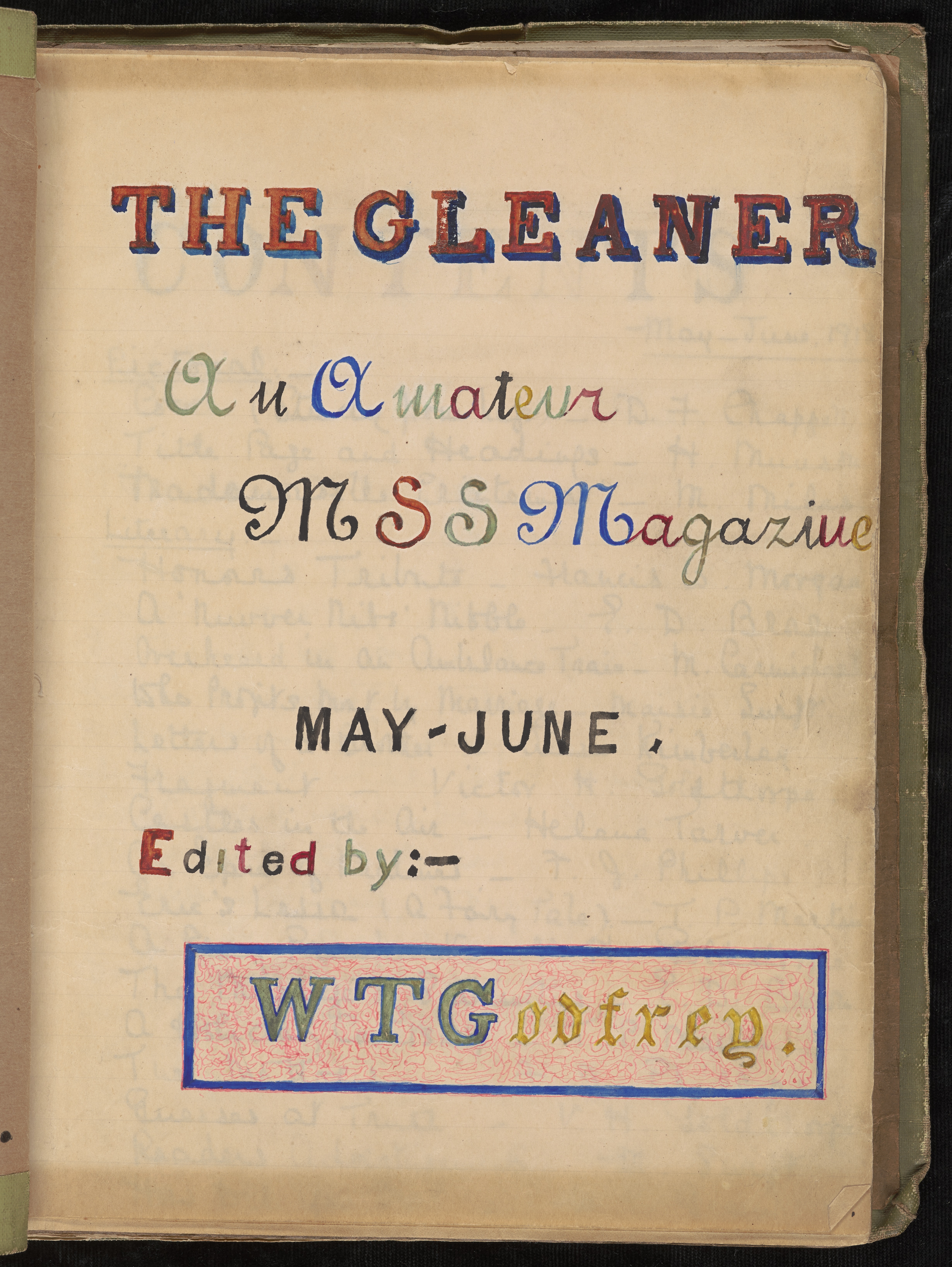

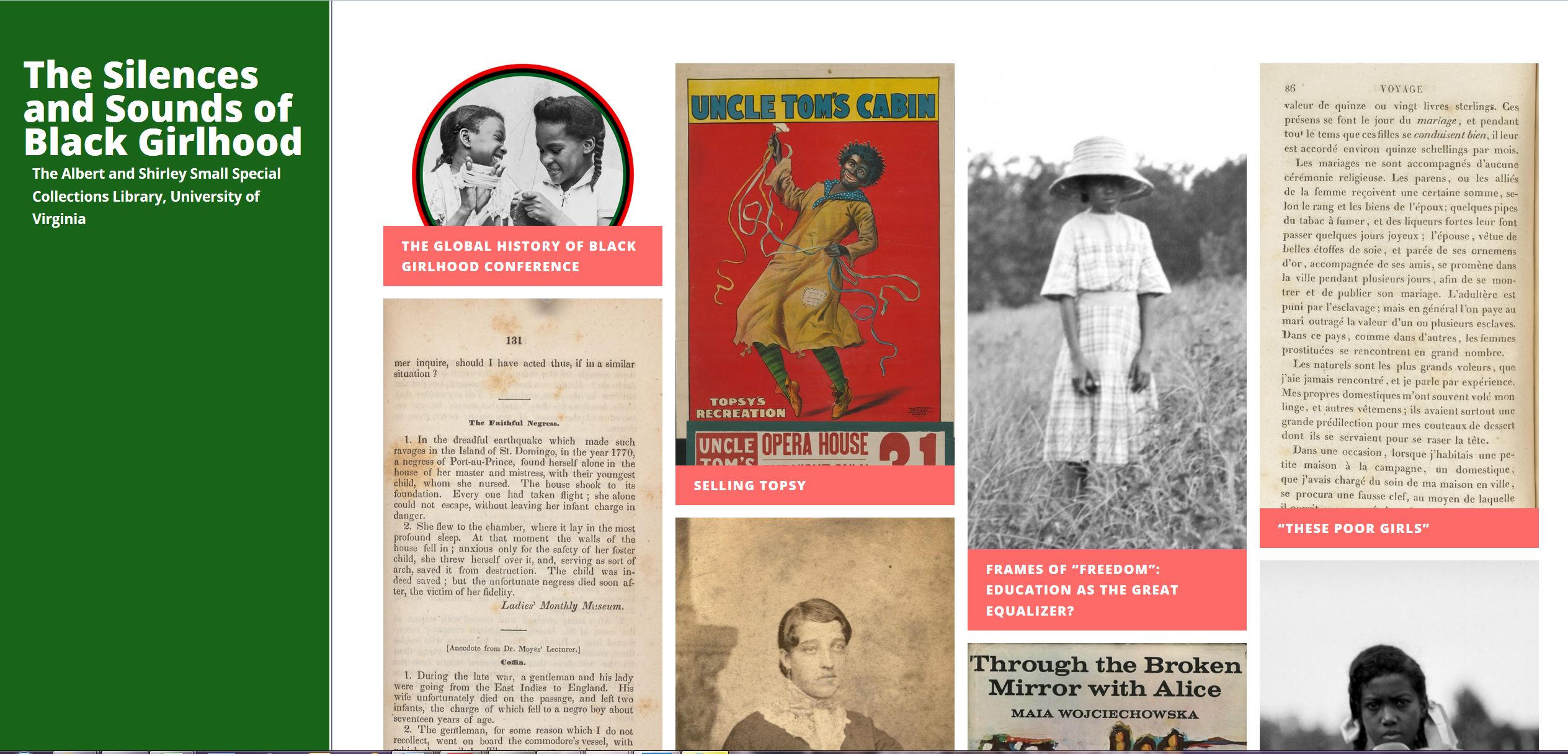

A screenshot of the blog that accompanies the exhibition. We encourage visitors to check it out to see the students’ hard work.

The key to this project was advanced planning. When I first decided to teach an advanced undergraduate seminar on the “Global History of Black Girlhood,” I met with Molly Schwartzburg to ask if it would be possible to produce a public history project from materials in Special Collections. Molly eagerly embraced the idea, volunteered her time, and most importantly, advised me on how to structure assignments so that students could complete the separate components of an exhibit on time. This early consultation enabled me to write an effective syllabus structured around the final project.

Because WGS is an interdisciplinary program, I knew most students in the seminar would not be historians and would likely be unfamiliar with archival research. To further complicate matters, sources on black girls are often hidden in larger collections and difficult to locate. It was therefore essential to provide students with some preliminary guide to relevant sources. The best resource was the expertise of Molly, Edward Gaynor, and other staff who pointed to numerous collections with promising material. Over the summer, Angel Nash, a Ph.D. student in the Curry School, worked with Edward and Molly to identify more sources and construct a bibliography of archival holdings at UVA related to black girlhood. By handing out this bibliography on the first day of class, I was able to give students the information they needed to hit the ground running.

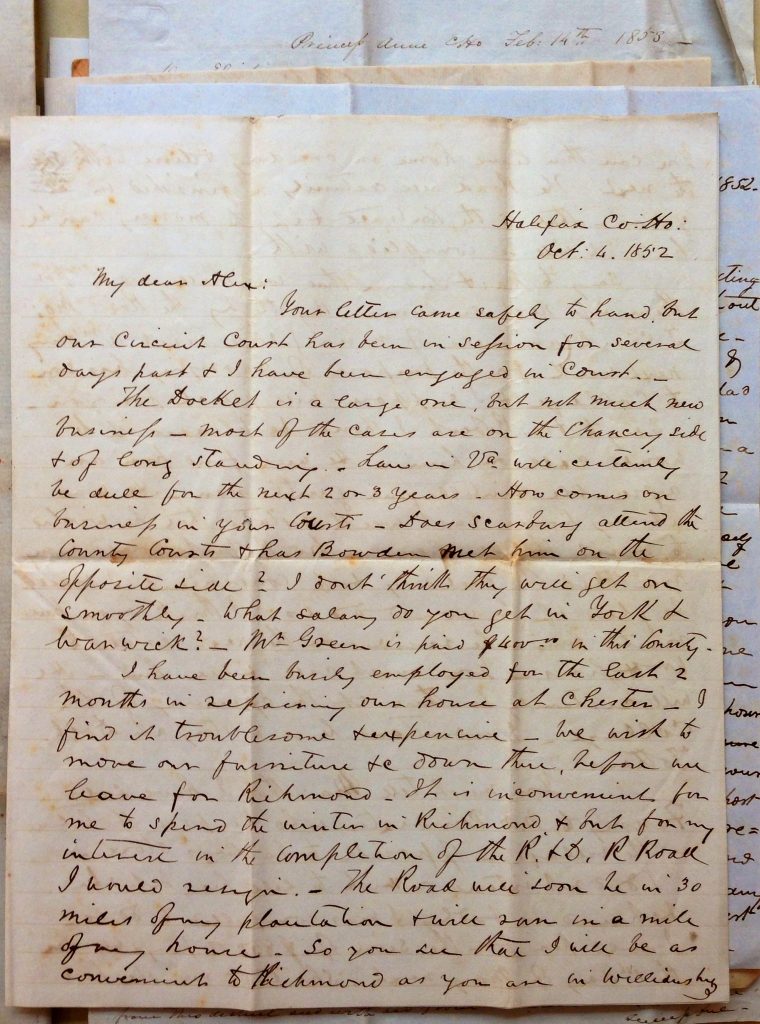

Molly then met with class to discuss strategies for locating other types of sources. This became a history lesson in itself as students discussed the changing language of race and the complications of searching for people categorized variously as African, Negro, colored, African American, or black. Molly helped students to think about how different types of sources—for example, eighteenth-century travelogues, nineteenth-century wills, or early twentieth-century photographs—might prompt different types of research questions. Finally, she helped students figure out how to pursue their own interests by studying the past.

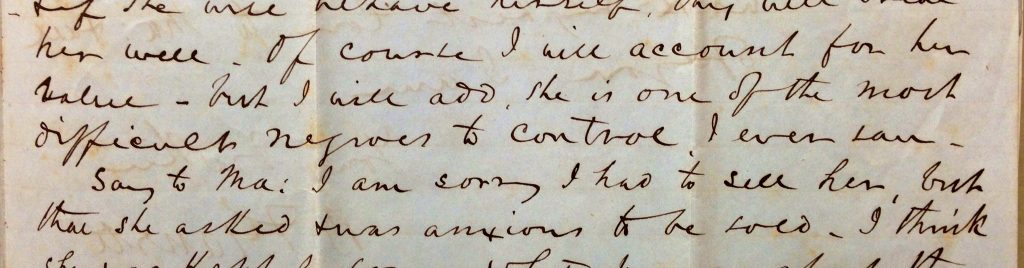

The best part came next as students went into Special Collections. Within two weeks, everyone in the class had identified a primary source that interested them and developed a plan for further research. The range of sources was amazing. For example, Nodjimadji Stringfellow found a 1820 memoir by a British official stationed on the Gold Coast. Dhanya Chittaranjan located a deed from a planter who presented his young granddaughter with the gift of an enslaved girl—”Martha Jane about six years old.” Diana Wilson, Emma McCallie, and Ivory Ibuaka all picked very different photographs from the Jackson Davis Collection. Lucas Dvorscak focused on a 1972 children’s book that retold the story of Alice in Wonderland with a black protagonist. Samantha Josey-Borden found an original edition of Ntozake Shange, for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf. Other students found sources exploring black girls’ labor; resistance to sexual violence; creativity; and political organizing.

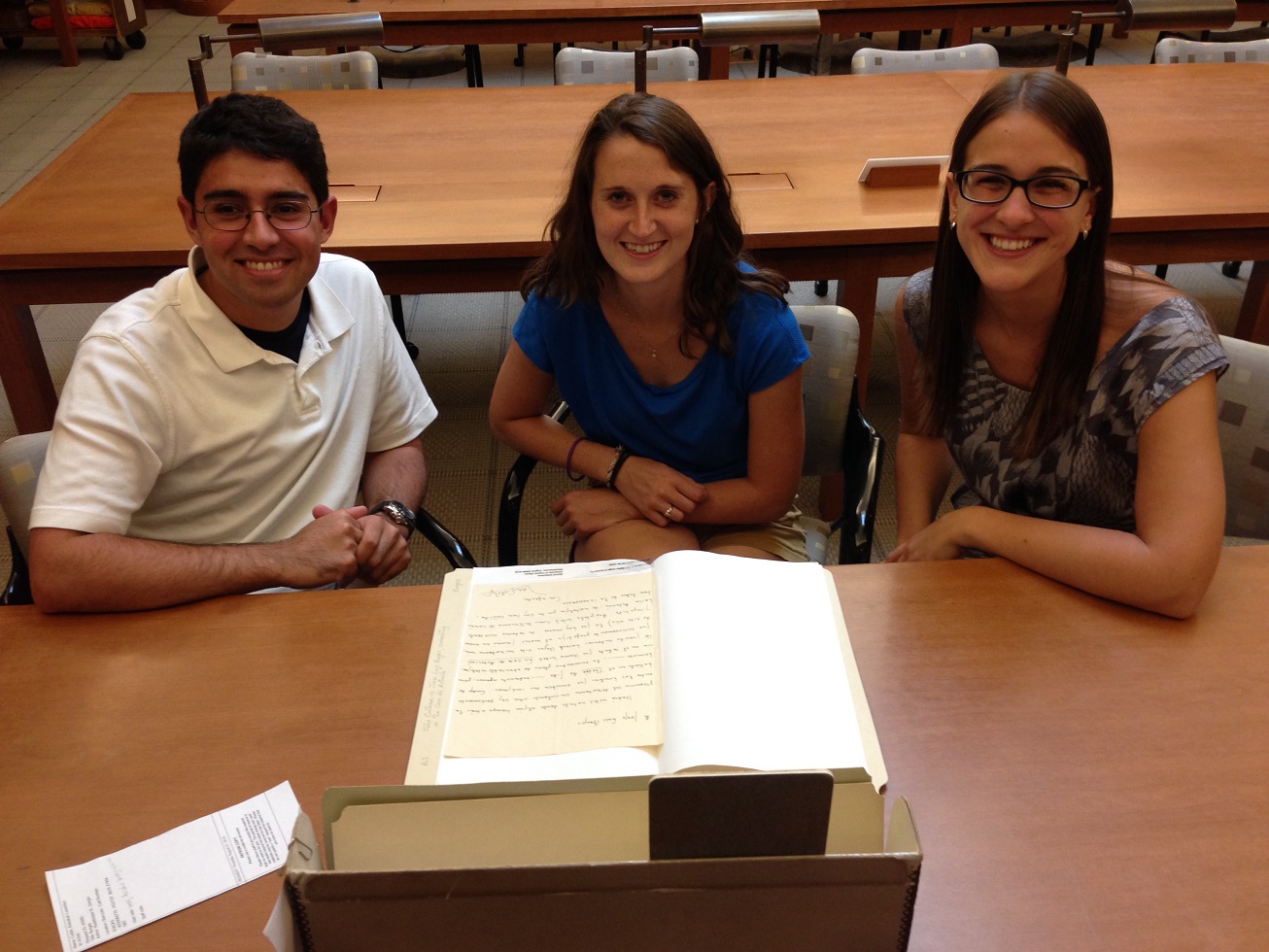

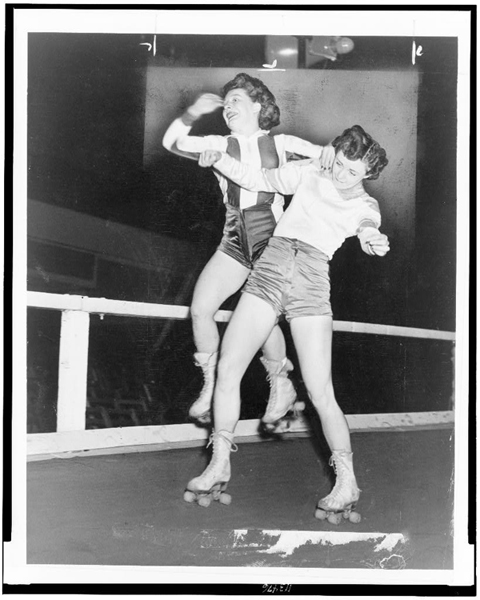

Some of the curators of the exhibition at the opening celebration with their instructor, Cori Field (far right).

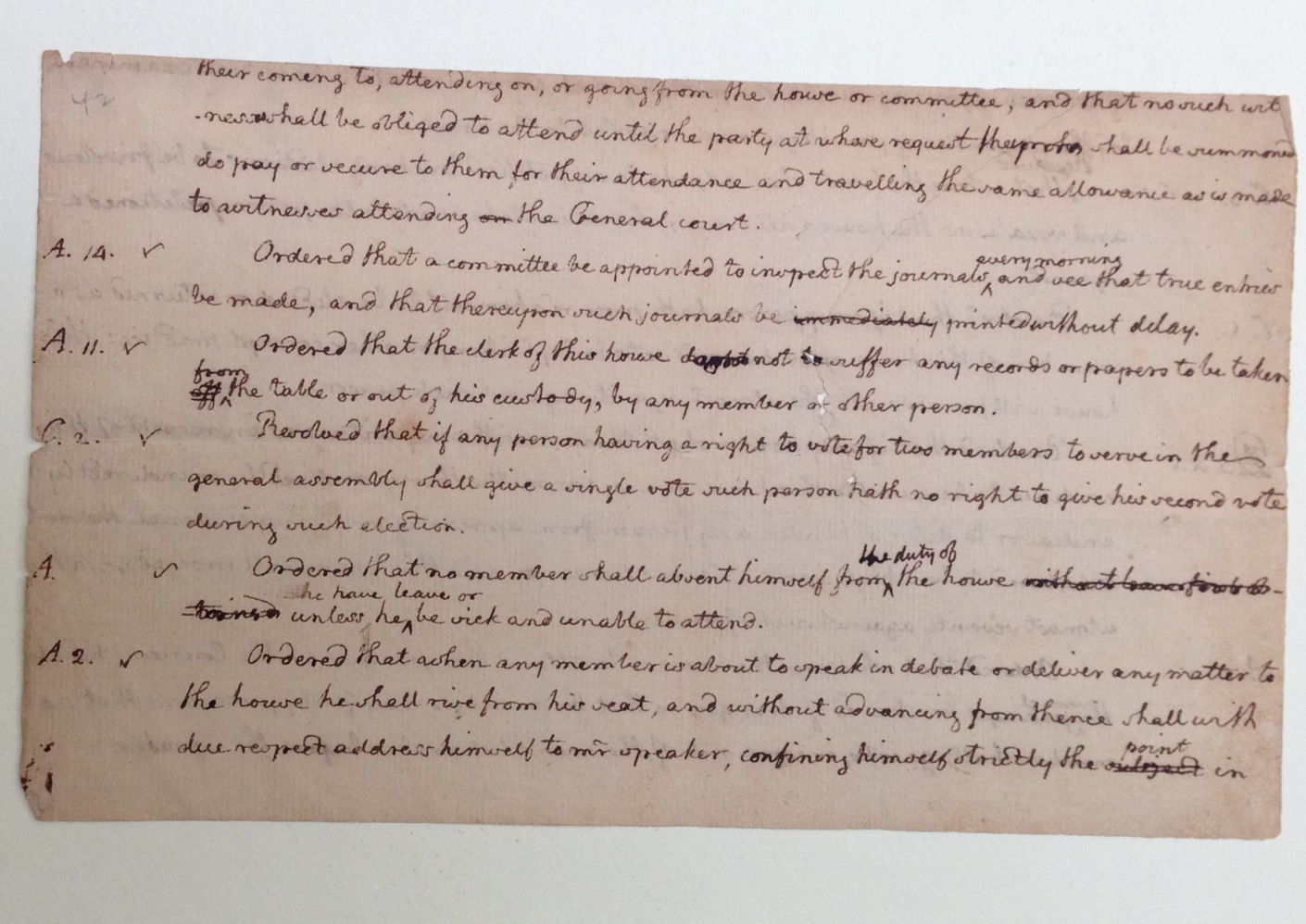

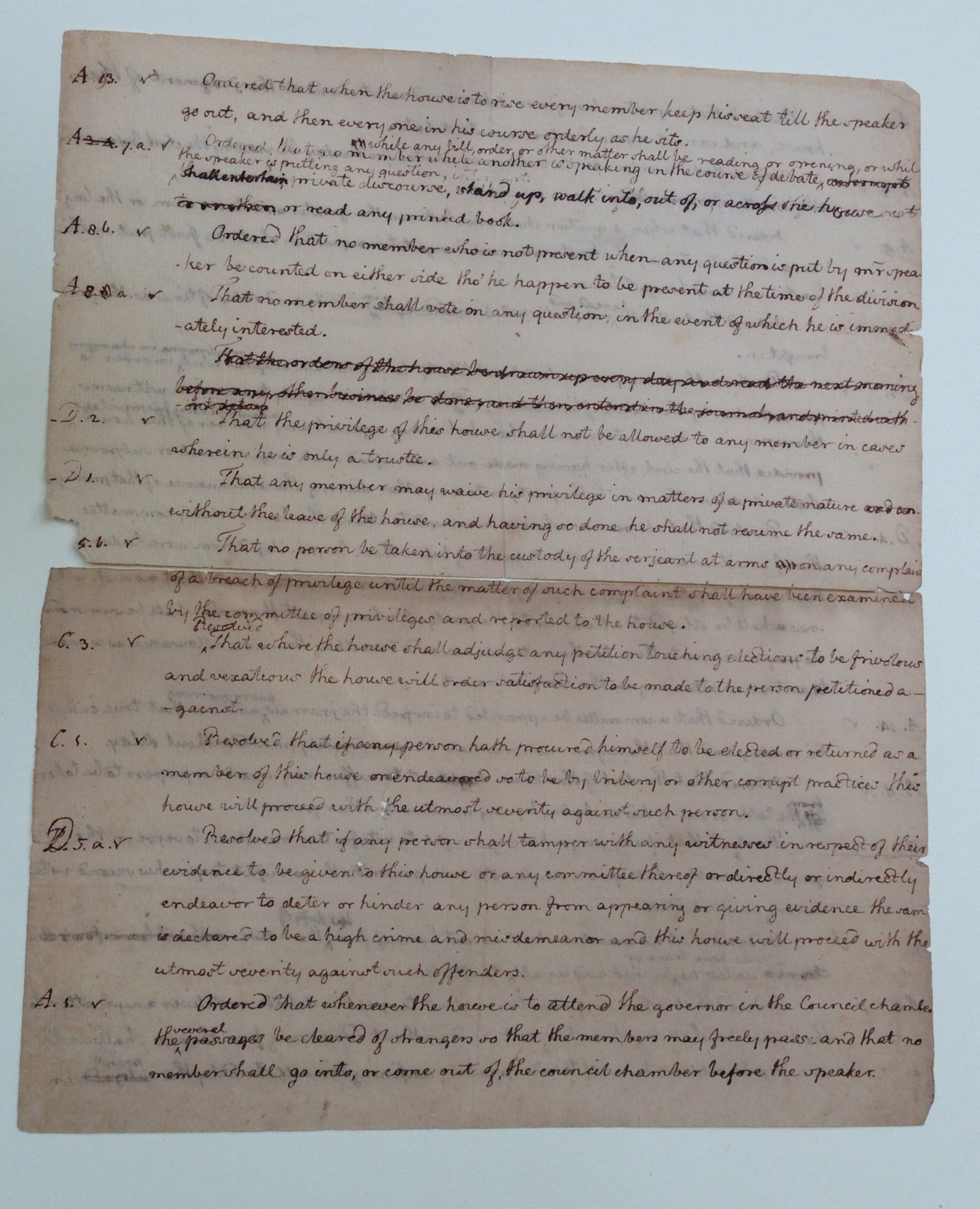

The next challenge was to combine these materials into a coherent exhibit. Once again, Molly provided guidance, encouraging students to begin with the exhibition space. We went to the exhibition hall, looked at the cases, and talked about how different items might fit. We then returned to the seminar room and discussed organizational strategies. Students quickly rejected a geographical or chronological approach and decided to organize the exhibit around key themes—but what themes? Together, students brainstormed ideas, eliminated some, voted for others and grouped their items into three broad categories of identity, resistance, and voice. They also thought about the physical properties of the items themselves and came up with the idea of enlarging two particularly striking images and hanging these on the wall as the entry to the exhibit.

The next challenge was locating secondary sources that would provide some historical context for every student. The subjet liaison for WGS, Erin Pappas, consulted with the whole class and then worked with individual students facing particularly difficult challenges. Some students who initially thought they couldn’t find any relevant information experienced the thrill of locating material, as when Erin helped Emily Breeding find information about the Lynchburg NAACP at Emory University. A quick call to Emory produced the information Emily needed for her article.

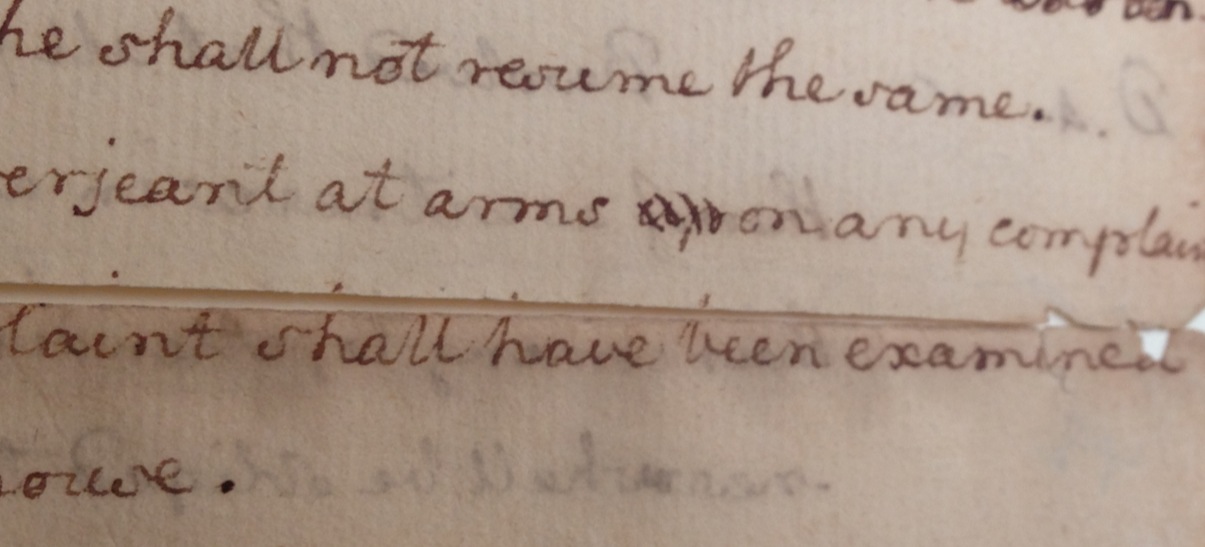

Condensing all of the information students had found into succinct labels was the greatest challenge of the course. Students were shocked to realize how little can be said in 150 words. Through multiple drafts, rigorous peer editing, and feedback from Molly and Holly, students all succeeded in crafting labels that draw the viewer in to the exhibit without providing too much detail. Writing longer articles enabled students to develop their insights in more detail for the accompanying blog.

Throughout this course, the students worked incredibly hard both on their own projects and on their thoughtful contributions to the collective project. I have never seen undergraduates edit each other’s work with such care and insight. The knowledge that this work mattered, that the exhibit would be available to the general public and visiting scholars, inspired a level of commitment and mutual support that is truly rare—in undergraduate seminars and in workplaces more generally. The students learned important skills in managing a complex project, working with others, and contributing to a shared product. At moments, they got incredibly frustrated, but then pulled together and took the project to a higher level. It was a true joy to be involved in this project.

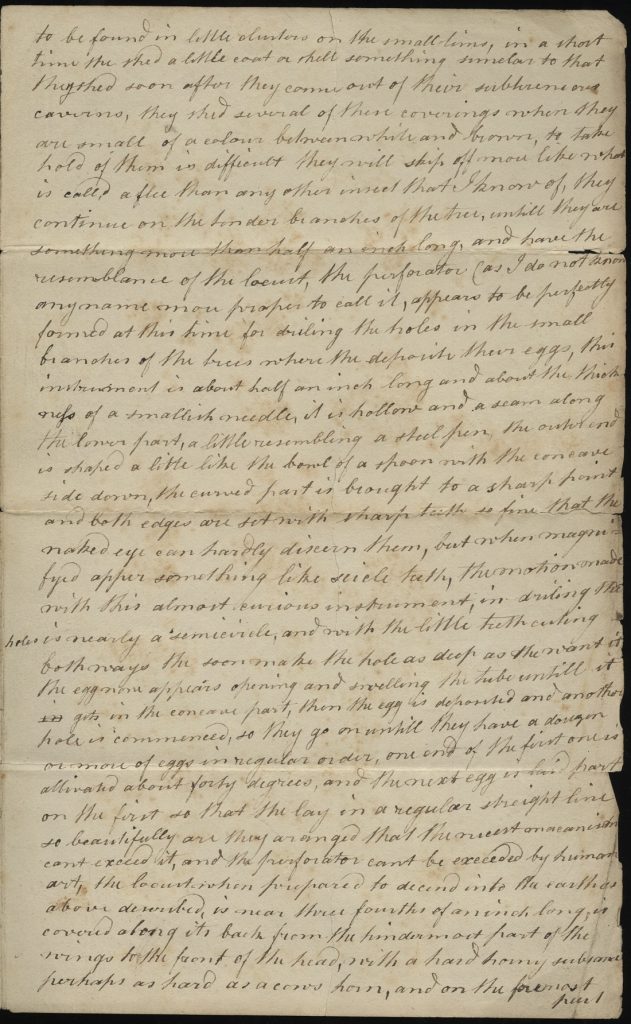

Visitors interact with the blog on an iPad and peruse the artifacts on display during the exhibition opening party.

“The Sounds and Silences of Black Girlhood” will be on view in the first floor gallery at the Harrison-Small building through March 24, 2017.