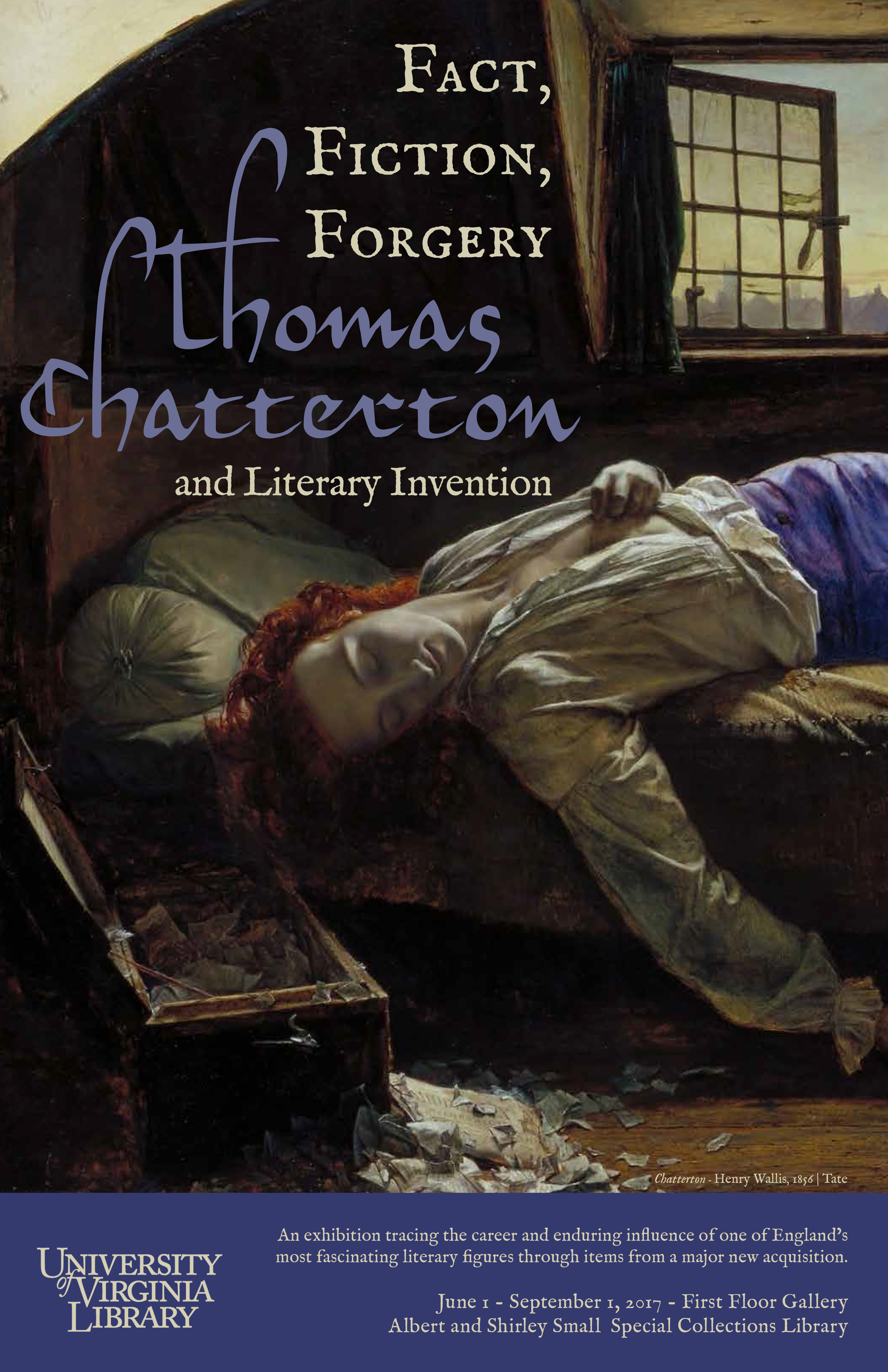

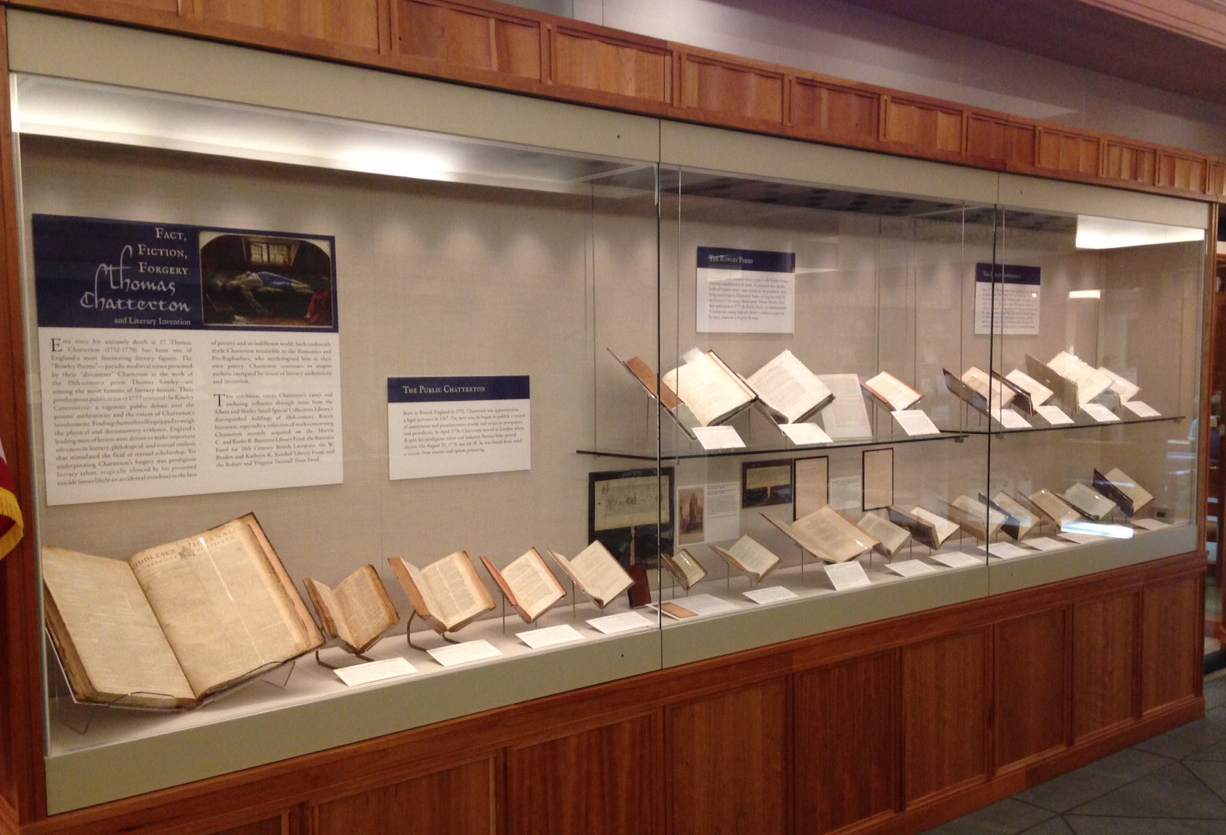

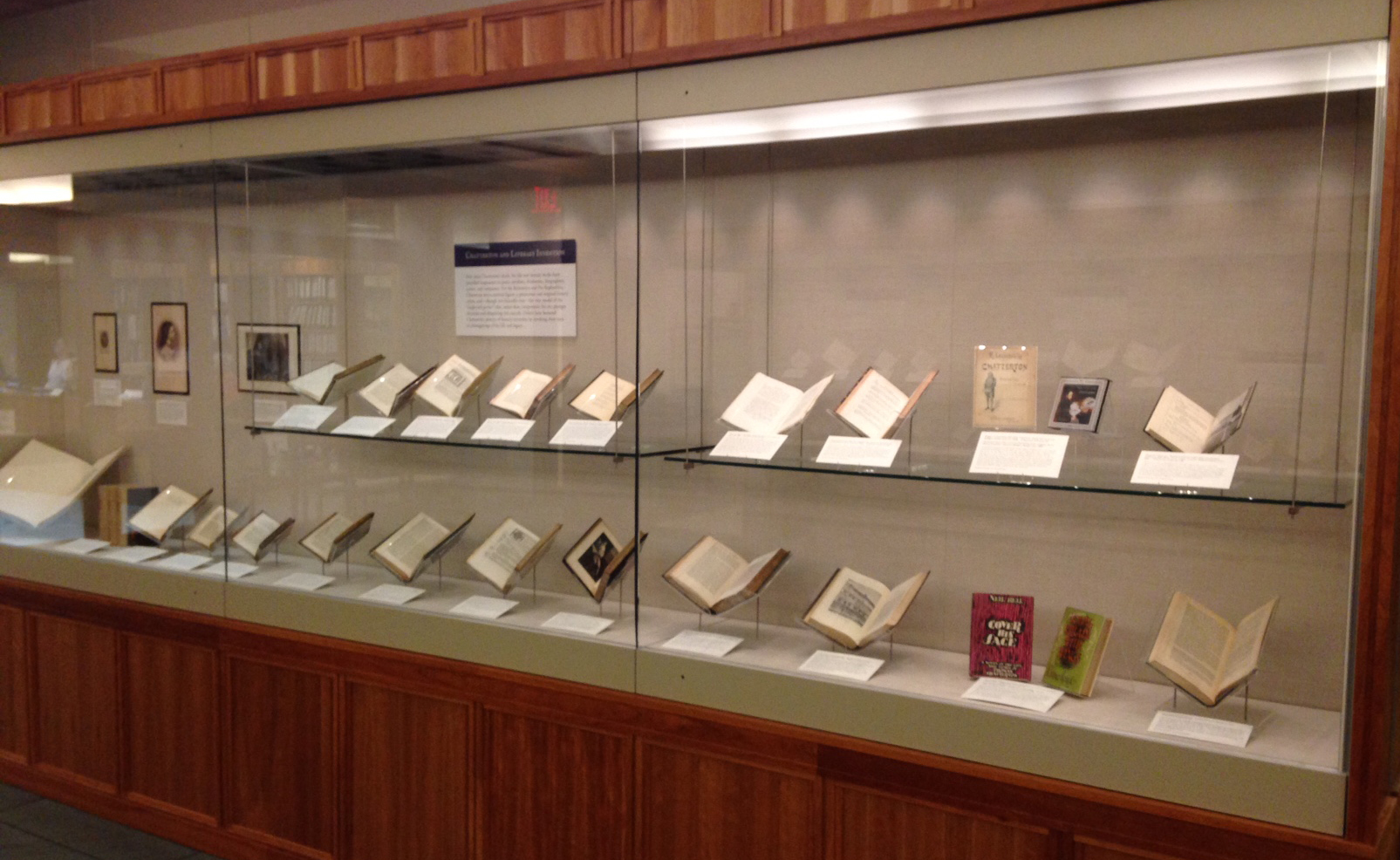

We are pleased to announce the opening of our latest First Floor Gallery exhibition, “Fact, Fiction, Forgery: Thomas Chatterton and Literary Invention,” which will remain on view through September 1, 2017. This exhibition, curated by David Whitesell, traces Chatterton’s career and enduring influence through books and manuscripts from U.Va.’s distinguished holdings of 18th-century British literature, in particular an important collection of works concerning Chatterton recently acquired on the Martin C. and Ruthe R. Battestin Library Fund, the Battestin Fund for 18th Century British Literature, the W. Braden and Kathryn K. Kerchof Library Fund, and the Robert and Virginia Tunstall Trust Fund.

We are pleased to announce the opening of our latest First Floor Gallery exhibition, “Fact, Fiction, Forgery: Thomas Chatterton and Literary Invention,” which will remain on view through September 1, 2017. This exhibition, curated by David Whitesell, traces Chatterton’s career and enduring influence through books and manuscripts from U.Va.’s distinguished holdings of 18th-century British literature, in particular an important collection of works concerning Chatterton recently acquired on the Martin C. and Ruthe R. Battestin Library Fund, the Battestin Fund for 18th Century British Literature, the W. Braden and Kathryn K. Kerchof Library Fund, and the Robert and Virginia Tunstall Trust Fund.

Ever since his untimely death at 17, Thomas Chatterton (1752-1770) has been one of England’s most fascinating literary figures. The “Rowley Poems”—pseudo-medieval verses presented by their “discoverer” Chatterton as the work of the 15th-century priest Thomas Rowley—are among the most famous of literary hoaxes. Their posthumous publication in 1777 initiated the Rowley Controversy: a vigorous public debate over the poems’ authenticity and the extent of Chatterton’s involvement. Finding themselves ill equipped to weigh the physical and documentary evidence, England’s leading men of letters were driven to make important advances in literary, philological, and textual analysis that stimulated the field of textual scholarship. Yet underpinning Chatterton’s forgery was prodigious literary talent, tragically silenced by his presumed suicide (more likely an accidental overdose) in the face of poverty and an indifferent world. Such credentials made Chatterton irresistible to the Romantics and Pre-Raphaelites, who mythologized him in their own poetry. Chatterton continues to inspire authors intrigued by issues of literary authenticity and invention.

Ever since his untimely death at 17, Thomas Chatterton (1752-1770) has been one of England’s most fascinating literary figures. The “Rowley Poems”—pseudo-medieval verses presented by their “discoverer” Chatterton as the work of the 15th-century priest Thomas Rowley—are among the most famous of literary hoaxes. Their posthumous publication in 1777 initiated the Rowley Controversy: a vigorous public debate over the poems’ authenticity and the extent of Chatterton’s involvement. Finding themselves ill equipped to weigh the physical and documentary evidence, England’s leading men of letters were driven to make important advances in literary, philological, and textual analysis that stimulated the field of textual scholarship. Yet underpinning Chatterton’s forgery was prodigious literary talent, tragically silenced by his presumed suicide (more likely an accidental overdose) in the face of poverty and an indifferent world. Such credentials made Chatterton irresistible to the Romantics and Pre-Raphaelites, who mythologized him in their own poetry. Chatterton continues to inspire authors intrigued by issues of literary authenticity and invention.

Born in Bristol, England in 1752, Chatterton was apprenticed as a legal scrivener in 1767. The next year he began to publish a torrent of anonymous and pseudonymous poems and essays in newspapers and periodicals. In April 1770 Chatterton moved to London where, despite his prodigious talent and industry, literary fame proved elusive. On August 25, 1770, not yet 18, he was found dead, ruled a suicide from arsenic and opium poisoning.

Born in Bristol, England in 1752, Chatterton was apprenticed as a legal scrivener in 1767. The next year he began to publish a torrent of anonymous and pseudonymous poems and essays in newspapers and periodicals. In April 1770 Chatterton moved to London where, despite his prodigious talent and industry, literary fame proved elusive. On August 25, 1770, not yet 18, he was found dead, ruled a suicide from arsenic and opium poisoning.

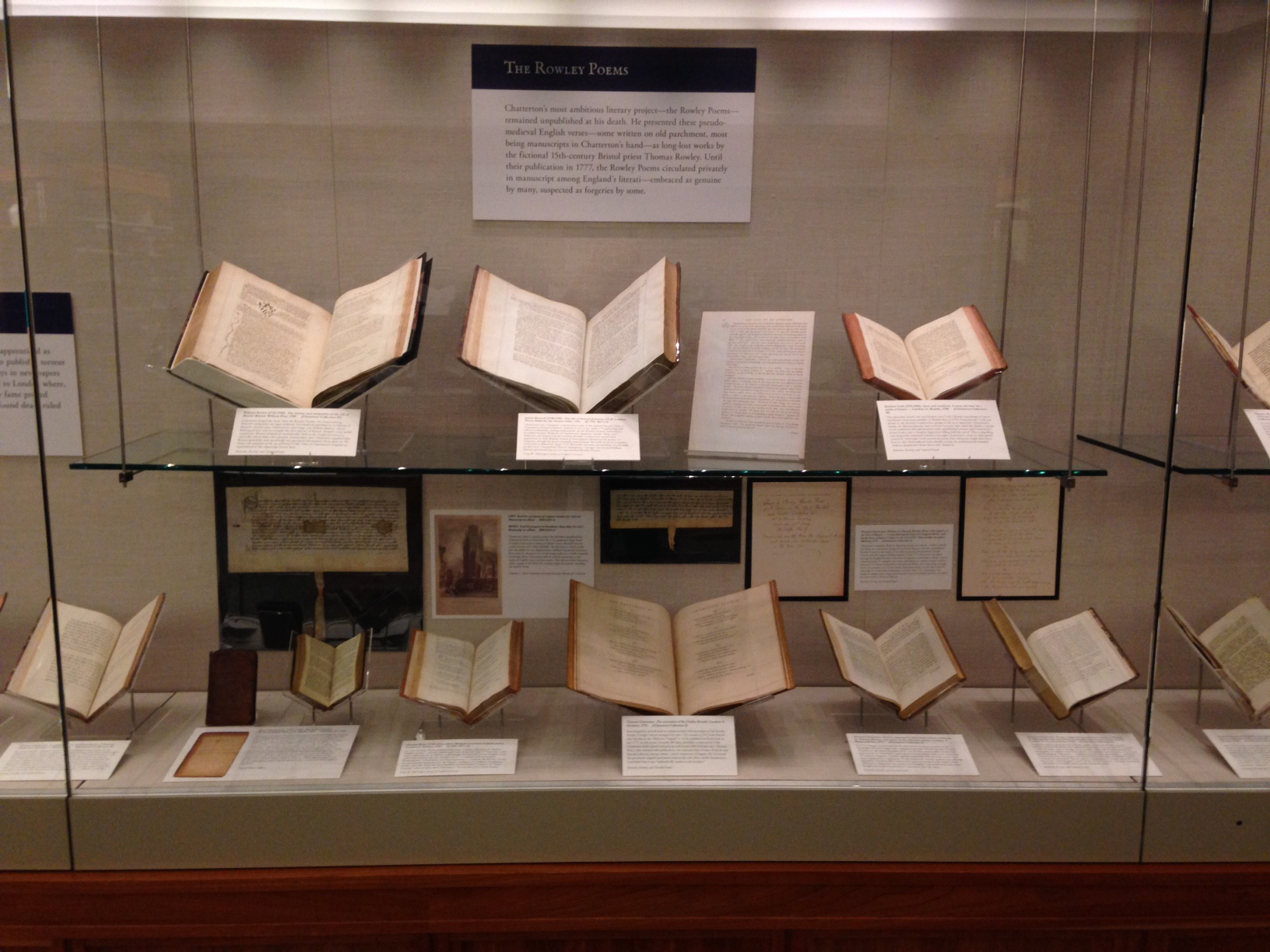

Chatterton’s most ambitious literary project—the Rowley Poems—remained unpublished at his death. He presented these mock-medieval English verses—some written on old parchment, most being manuscripts in Chatterton’s hand—as long-lost works by the fictional 15th-century Bristol priest Thomas Rowley. Until their publication in 1777, the Rowley Poems circulated privately in manuscript among England’s literati—embraced as genuine by many, suspected as forgeries by some.

Chatterton’s most ambitious literary project—the Rowley Poems—remained unpublished at his death. He presented these mock-medieval English verses—some written on old parchment, most being manuscripts in Chatterton’s hand—as long-lost works by the fictional 15th-century Bristol priest Thomas Rowley. Until their publication in 1777, the Rowley Poems circulated privately in manuscript among England’s literati—embraced as genuine by many, suspected as forgeries by some.

From 1777 to 1782 the Rowley Poems’ authenticity was vigorously debated in print. Their literary merit was undisputed. But could the poems, written in stilted “Rowleian dialect” in a diversity of styles, be genuine 15th-century works? If forgeries, could they truly be creations of a teenage apprentice? Stoking the debate were the tragic circumstances of Chatterton’s death, personal rivalries, the differing perspectives of antiquaries and scholars, and the inability of existing scholarly methods to settle the matter. The controversy prompted significant advances in textual scholarship.

From 1777 to 1782 the Rowley Poems’ authenticity was vigorously debated in print. Their literary merit was undisputed. But could the poems, written in stilted “Rowleian dialect” in a diversity of styles, be genuine 15th-century works? If forgeries, could they truly be creations of a teenage apprentice? Stoking the debate were the tragic circumstances of Chatterton’s death, personal rivalries, the differing perspectives of antiquaries and scholars, and the inability of existing scholarly methods to settle the matter. The controversy prompted significant advances in textual scholarship.

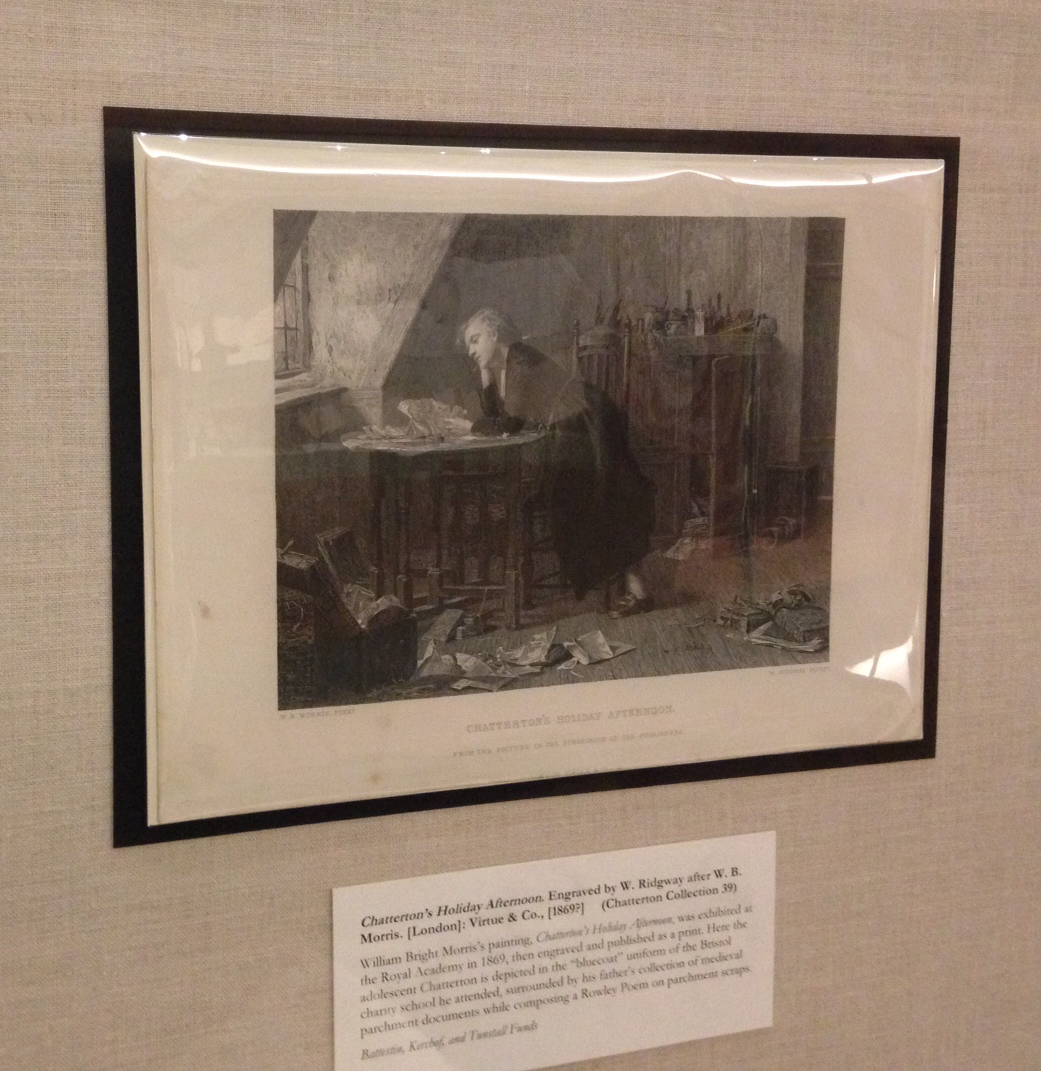

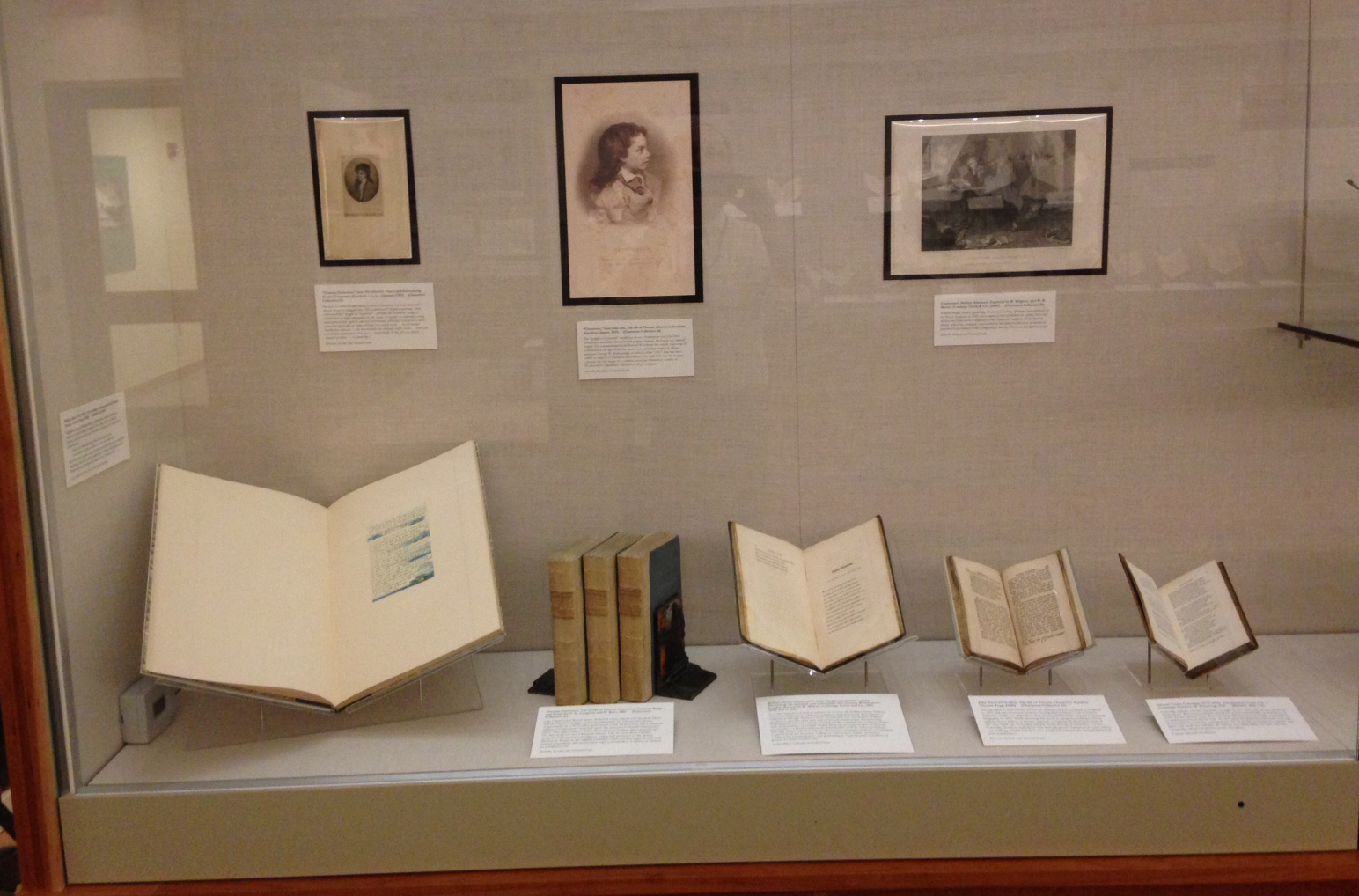

Ever since Chatterton’s death, his life and literary works have provided inspiration to poets, novelists, dramatists, biographers, artists, and composers. For the Romantics and Pre-Raphaelites, Chatterton was a seminal figure: a precocious and original literary talent, and—though not factually true—the very model of the “neglected genius” who, rather than compromise his art, plunges destitute and despairing into suicide. Others have honored Chatterton’s powers of literary invention by invoking their own in reimaginings of his life and legacy.

Ever since Chatterton’s death, his life and literary works have provided inspiration to poets, novelists, dramatists, biographers, artists, and composers. For the Romantics and Pre-Raphaelites, Chatterton was a seminal figure: a precocious and original literary talent, and—though not factually true—the very model of the “neglected genius” who, rather than compromise his art, plunges destitute and despairing into suicide. Others have honored Chatterton’s powers of literary invention by invoking their own in reimaginings of his life and legacy.