Tax records are probably the last thing you would think that Special Collections libraries possess. However, along with our many books, photographs, letters, drawings, and more, the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library has financial records, such as tax materials, in its many collections documenting the life and work of people and their businesses. These records document how citizens pay the government for services and benefits, and as such reveal much about those citizens’ work, but they also serve a secondary use: for instance, a tax form close at hand might become the surface for a draft of a literary work. This post shows both utilities of these most ubiquitous records through their use by the famous–and infamous.

Imagining Thomas Jefferson’s Debt and Wealth Through Sheriff Ledgers

In colonial Albemarle County, Virginia, as in some other Virginia counties, the sheriff collected taxes. Thomas Jefferson, as a major plantation and slave owner, was, of course, not exempt from these taxes.

Image of Thomas Jefferson, engraved by T. Johnson from the painting by Gilbert Stuart. (MSS 5845. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

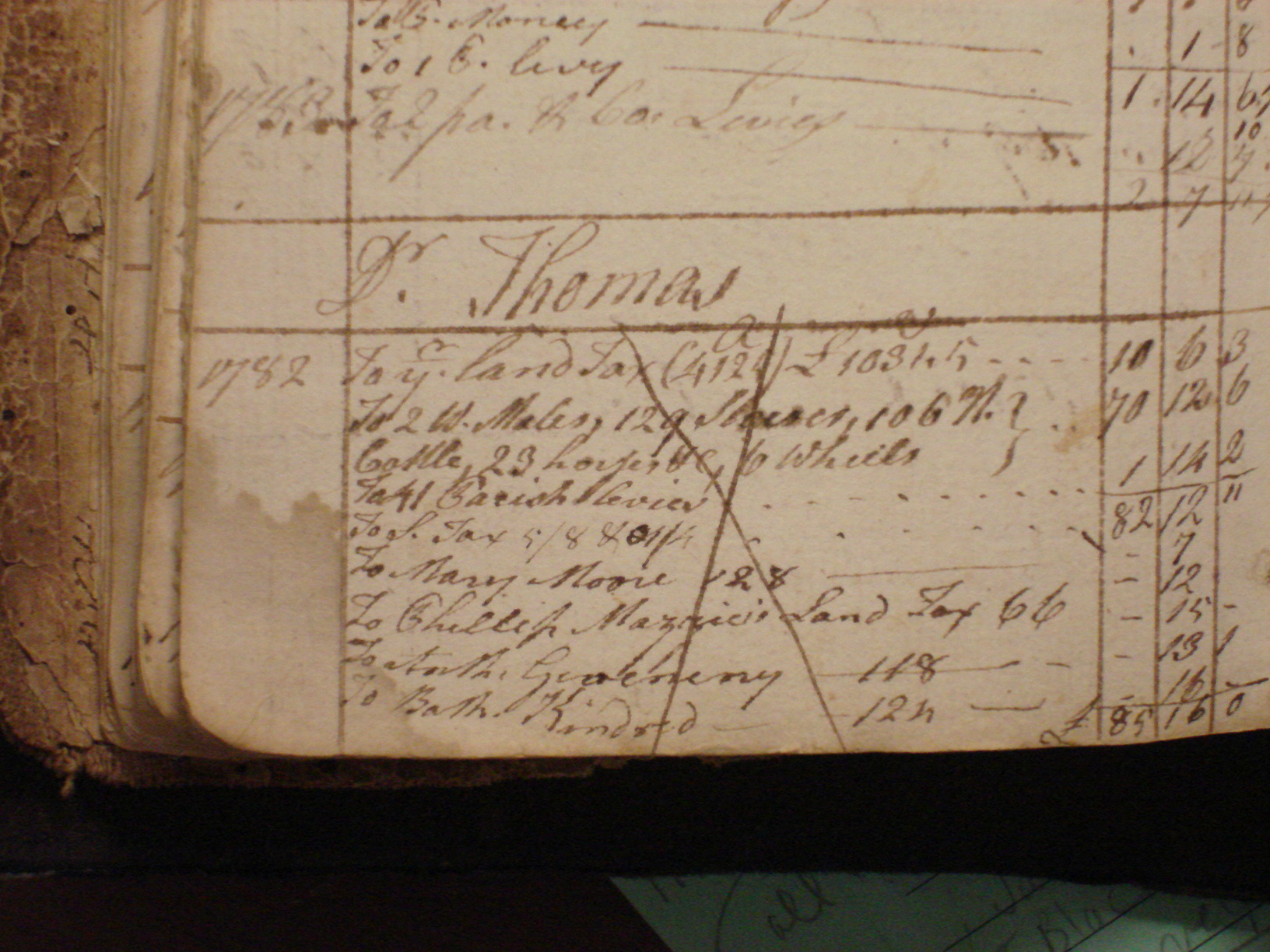

During the American Revolutionary War, Nicholas Hamner was the Sheriff of Albemarle County. As a duty of his office, he kept a ledger of all of the citizens who owed and paid taxes in the county. We hold one of those ledgers, dated from 1782-1783, the last two years of the Revolutionary War. Shown here is the tax assessment for Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson was taxed on his land and moveable property, including his slaves and cattle. He also had to pay a parish levy, which covers ministers’ salaries, church upkeep, and aid to the poor and orphans:

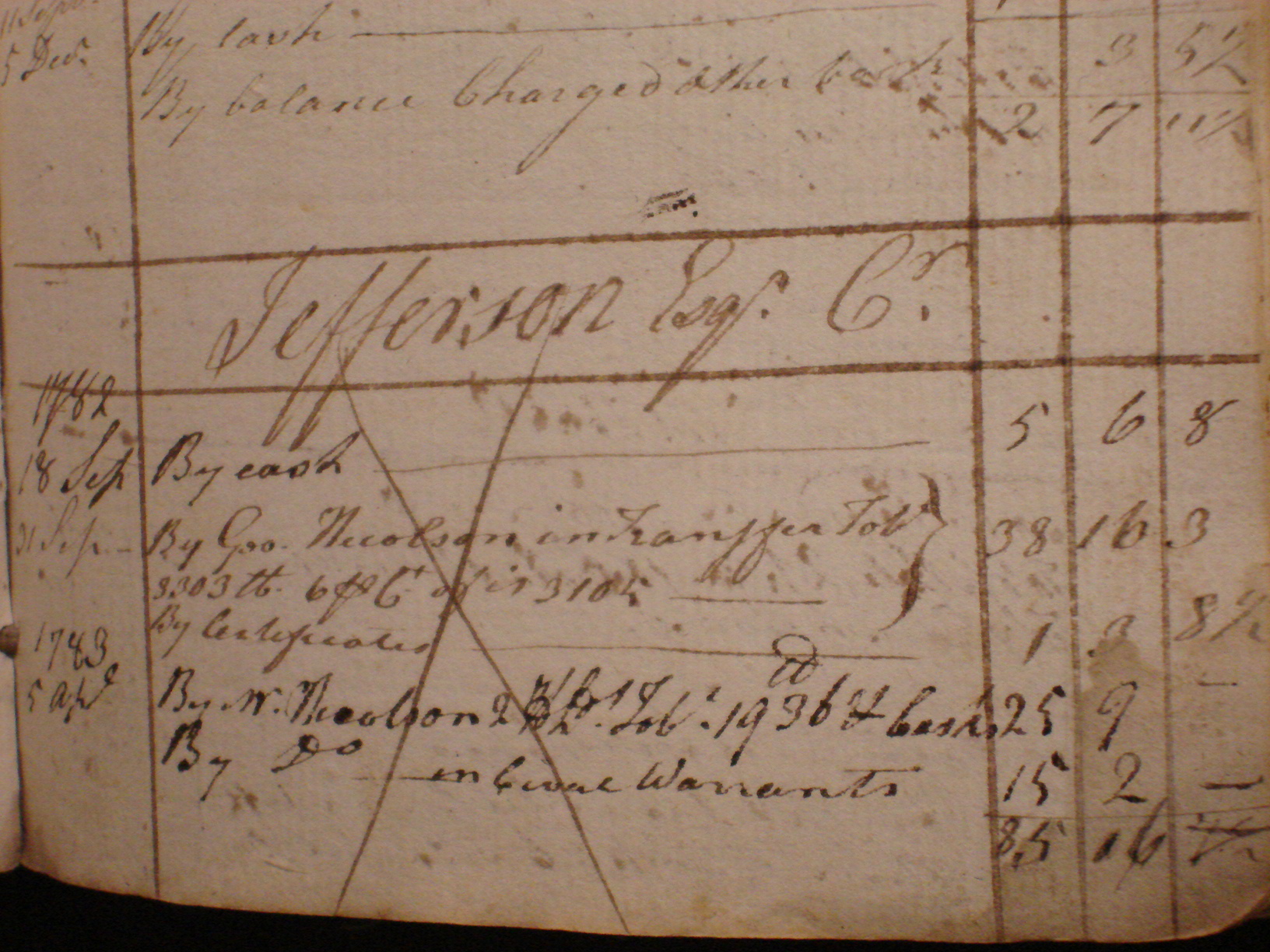

Nicholas Hamner’s Sheriff’s Ledger for the assessment of taxes in Albemarle County, Va. for the year 1782, opened to the page spread numbered 49. The last entry on the spread is Thomas Jefferson. On the verso (left) is the list of debts/taxes he has to pay, while on the recto (right) is the list of tax credits/payments he has made. (MSS 3455. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Detail of Jefferson’s debt or taxes owed for the year 1782. The taxes were all assessed in British Pounds. Here you can see that Jefferson has to pay a land tax, a poll tax for two white males, a property tax on 129 slaves, 23 horses and six wheels. He also has to pay parish levies, which defrays the cost of ministers, upkeep of the churches, and aid to the poor and orphans. Further research might explain how or why he was assessed for the named people on the list, such as Mary Moore. (MSS 3455. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Detail of Jefferson’s credits or payment of his taxes for 1782. On September 18, 1782, 12 days after the death of his wife Martha, Jefferson paid part of his taxes by cash. He also paid by way of George Nicolson and W. Nicolson; a tax historian might be able to explain this detail. Jefferson has a zero balance by April of the following year 1783.

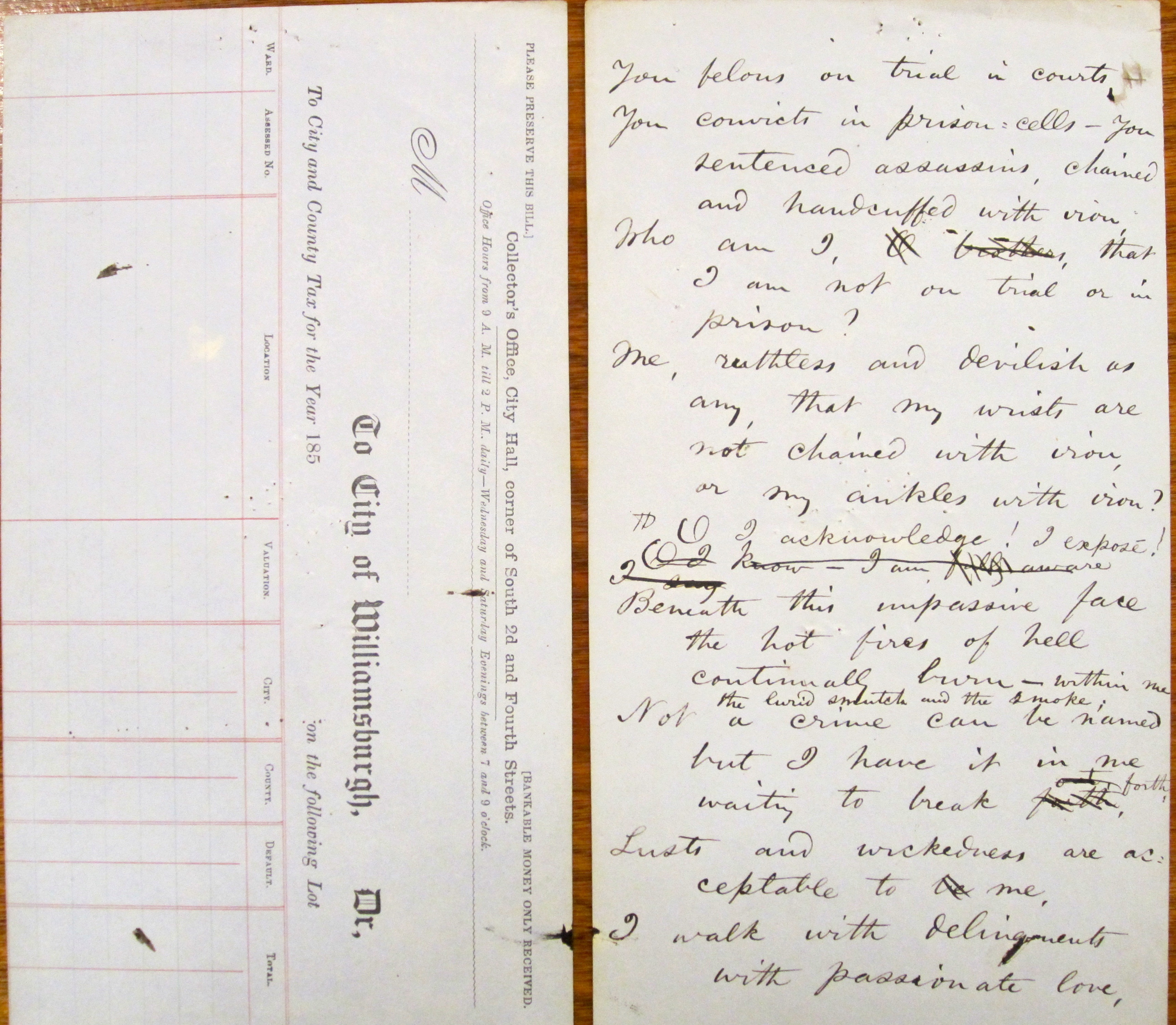

Seeing the Evolution of Walt Whitman’s Poetry Through His Chosen Surface: Tax Forms

Poet Walt Whitman lived, worked as a journalist, and wrote poetry in New York during the 1840s and 1850s. It is here that he composed his poems for the third edition of Leaves of Grass. He wrote his poems on scraps of paper. Some of the paper were melon-colored, while others were plain, and still more were actual tax forms from the city of Williamsburgh (Brooklyn). Whitman worked in a print shop as well as at the Brooklyn Times, so it is likely the paper was produced as part of a job printing at one of his places of employment. The Special Collections Library holds a number of handwritten poetry drafts on these particular tax forms, as part of the massive fragmentary draft for the third edition of Leaves of Grass, one of the cornerstones of the Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature. Fredson Bowers, bibliographer and professor of English at the University of Virginia from 1938 to 1975, used all manner of physical evidence available to him in these artifacts to reconstruct the manuscript’s likely original order.

Engraving of Walt Whitman from the frontispiece of the third edition, first issue of Leaves of Grass (PS 3201. 1860 copy 4, Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

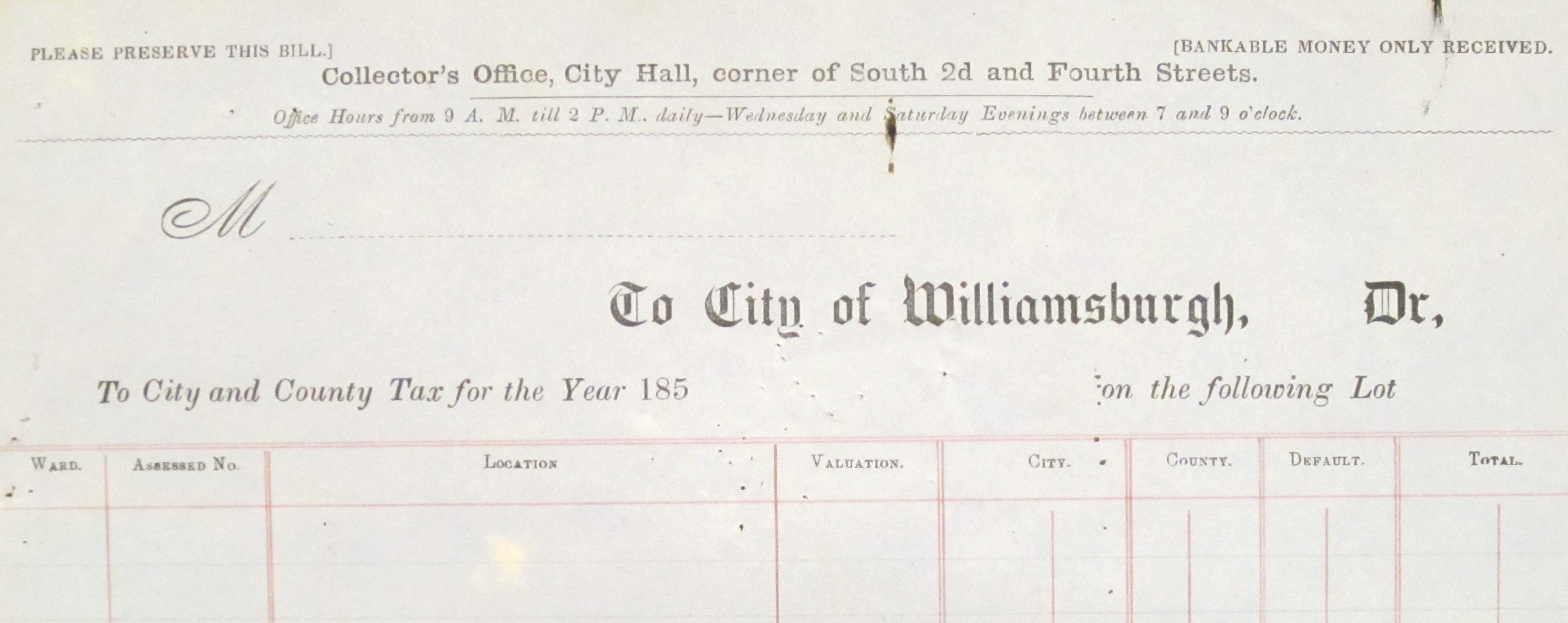

Whitman drafted his poems on all different scraps of paper, including the backs of tax forms from the City of Williamsburgh [Brooklyn, NY]. During the 1850s, Whitman worked at a printing shop and the Brooklyn Times newspaper, where it is likely that they did many job printings, including these tax forms. This featured manuscript copy of a poem, written on the back of the tax form, would later become part of the third edition of Leaves of Grass. (MSS 3829, Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Detail of tax form on which Whitman wrote some of his poems for the third edition of Leaves of Grass. (MSS 3829, Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Reading Hitler’s Rise Through His Falling Taxes

Oron Hale was an historian, University of Virginia professor, U.S. Army Major with the Intelligence Division of the War Department during World War II, and Commissioner for Bavaria with the U.S. High Commissioner for Germany. During his government service in Germany, he witnessed first-hand the rise of Hitler and National Socialism in Europe; after the war he took part in a special mission of the U.S. War Department’s Historical (Shuster) Commission in Germany, interrogating the surviving defeated leaders of the Third Reich, including Hermann Göring, Wilhelm Keitel, Karl Dönitz, and Joachim von Ribbentrop among others.

The Oron Hale Papers at the Special Collections Library include his personal and office correspondence, manuscripts of his published writings, records relating to his academic activities and government service in Germany, and declassified intelligence reports. One unexpected, and fascinating component of the collection is the set of contemporary photostats of Adolf Hitler’s tax returns from 1925 through 1935, which were among the documents seized by the Allies during the war.

Photograph of Oron J. Hale, ca. 1942. At the time of this photograph, Hale was a U.S. Major, serving with the Intelligence Division of the War Department General Staff in Washington. (MSS 12800-a. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Hitler’s taxes show his metamorphosis from struggling writer to powerful–and financially well-off–dictator in a relatively short amount of time.

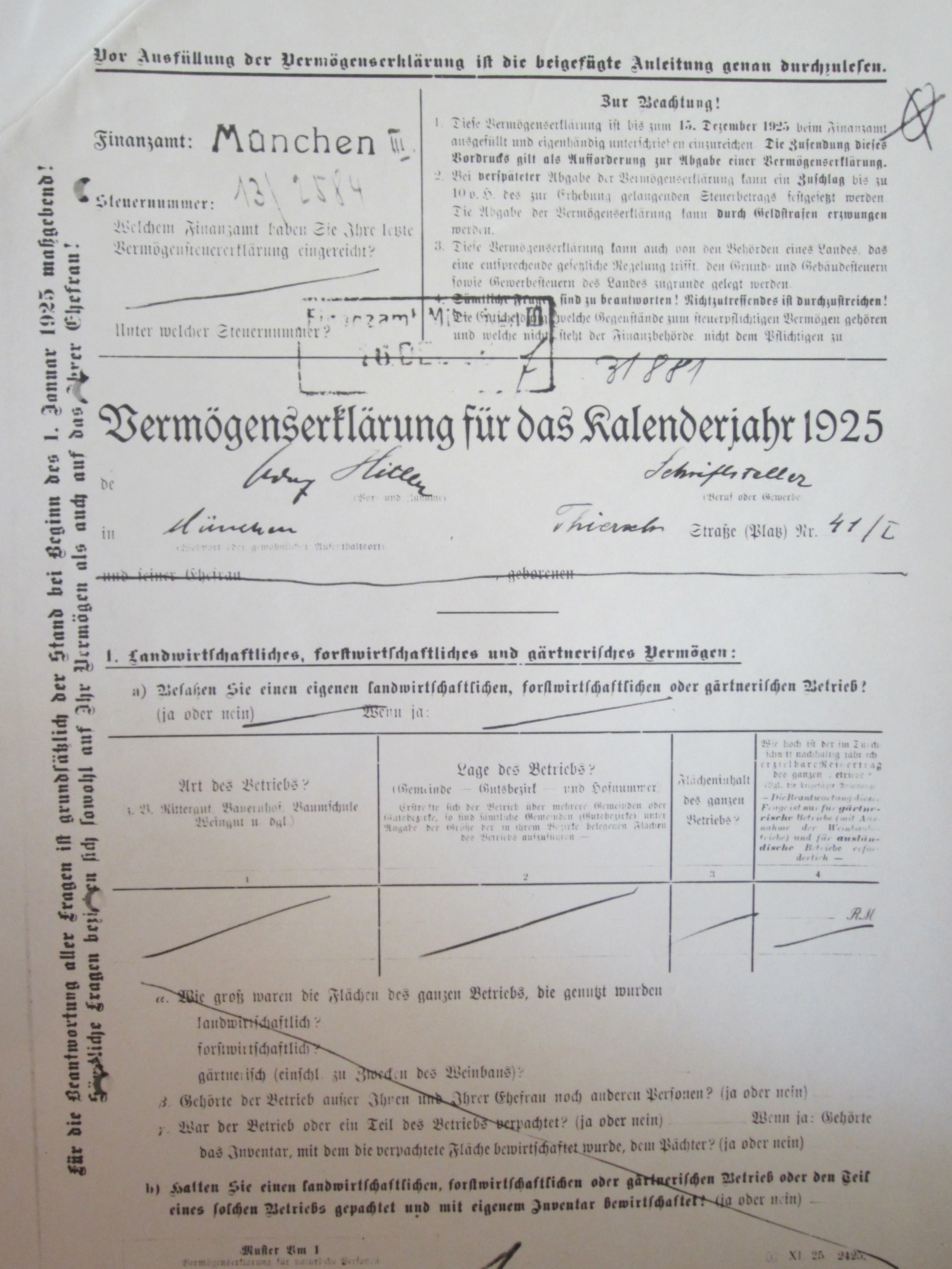

First page of Hitler’s completed 1925 tax forms. Here you can see his signature and the statement of his profession as writer (Schriftsteller) from Munich (München). He owns no real estate property. (MSS 12800-a. Photograph by Petrina Jackson.)

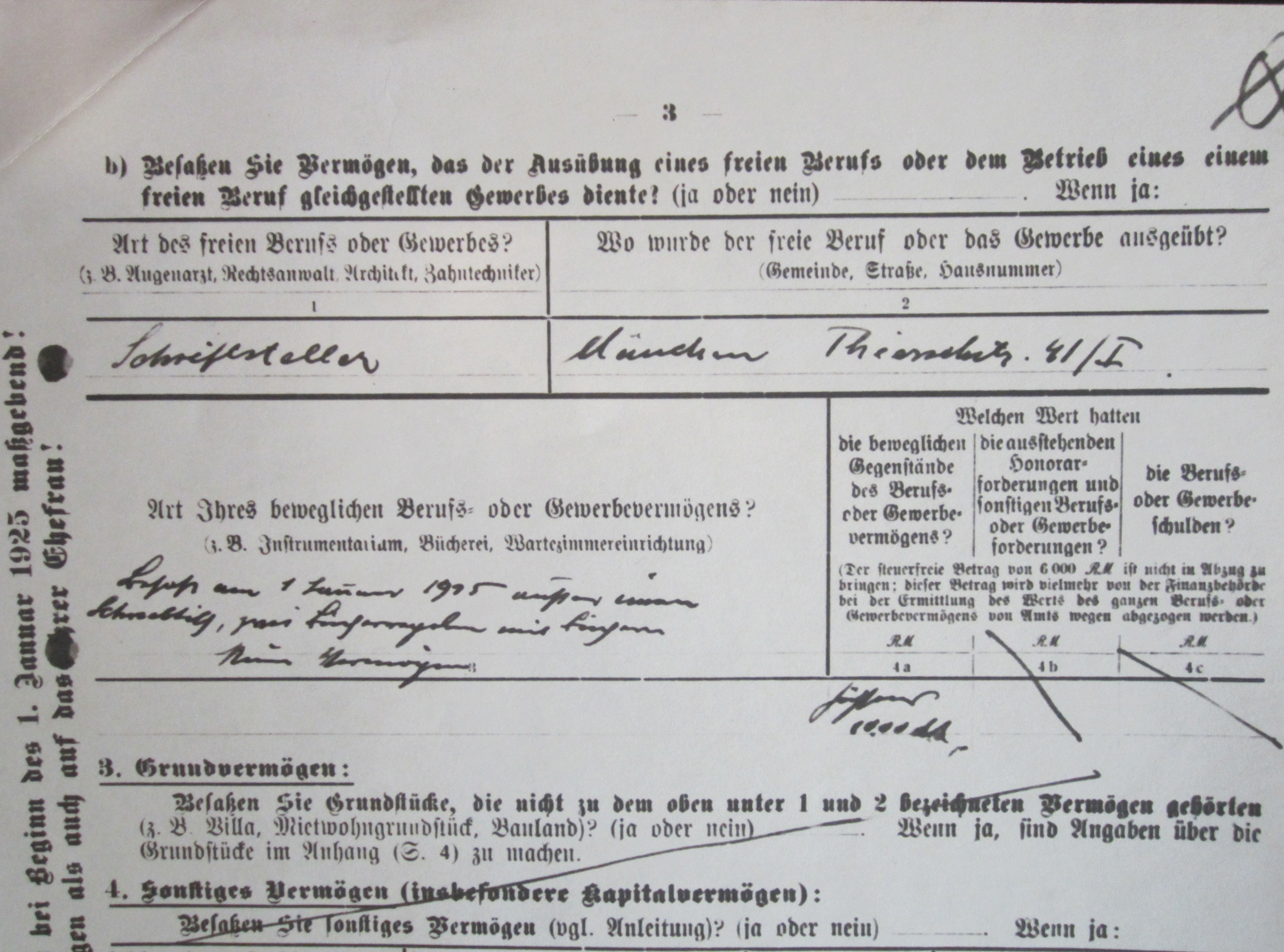

On page 3 of Hitler’s 1925 tax form, Hitler’s property tax declaration is limited to one writing desk and two bookshelves with books. The combined cost of those items was 1000 Reichsmark. (MSS 12800-a. Photograph by Petrina Jackson)

Here are some other points of interest in his tax files found in notes, translated by Hale, from Hitler’s tax files:

In 1925, Hitler buys a motor-car II A 6699 in February 1925 for 20.000 Reichsmark (RM), but must explain to the tax office where he got the money for this purchase. He responds that he borrows it from a bank. In this year he also asks for an extension to pay his taxes by installments.

In 1933, the Minister of Finance makes a decision that Hitler is not to pay any income tax on his fees as Reichskanzler (chancellor of the empire).

In 1934, The Reichsminister of Finance decides that Hitler may deduct 50% of his income as propaganda costs.

The final translated note is from Dr. Lizius (senior finance government official and manager of finances for Munich-West), and it reads: “On Febr. 25, 1935 President Mirre called me by telephone and said, that Staatssekretär Reinhardt had informed the Führer of the apprehension concerning his exemption from taxation as Head of the State and that the Führer dealt the opinion of Herr Mirre and Reinhardt. The order, that the Führer should be tax-free, thereby would be final. Upon that I withdrew all records of the Führer from the ordinary business performance and put them under lock.”

These documents–and those of Thomas Jefferson and Walt Whitman–are a very particular kind of historical evidence, and our collections are replete with other fascinating examples. Who knew tax records weren’t just mundane frustrations we are happy to file away as quickly as possible each year? And who knows what stories our own tax forms might tell someday?

***

I would like to extend a special thanks to Chad Wellmon, assistant professor of Germanic languages and literatures for helping me by translating into English the German tax documents.

I would also like to give a special thanks to my colleagues Heather Riser, Special Collections’ head of reference and research services, and Donna Stapley, Assistant to the Special Collections director, for their research help with interpreting the 1782 Sheriff’s ledger.