The holidays are upon us! As we watch the students head home, the weather cool (well…not as much as we might like), and twinkling lights appear all over town, we are adding to the holiday mood with a special post from Reference Coordinator Regina “Ms. Claus” Rush. Enjoy, and be sure to check our website for holiday hours in the next couple of weeks. Thanks for the movie recommendation, Regina!

Inquire of any of my colleagues at Special Collections Library and they will attest that I govern my life by the Golden Rule. No, not that Golden Rule. I follow the Golden Rule according to Ebenezer Scrooge. Allow me to clarify further: not the Bah-Humbug Scrooge, but the kinder-gentler-post-three-ghostly-visitations Scrooge. His Golden Rule reads, “I will honour Christmas in my heart and try to keep it all year!”

Throughout the year, my colleagues can count on me to daily mention a Christmas movie, sing a verse or two from a favorite Christmas carol, or contemplate my plans for the coming year’s Christmas tree themes for my home. These are ways that I keep the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Future at bay. So when asked by my colleague Molly Schwartzburg to write a post highlighting an item from our collection pertaining to Christmas, quicker than “Jack Frost can nibble at your nose,” I. WAS. ON. IT!

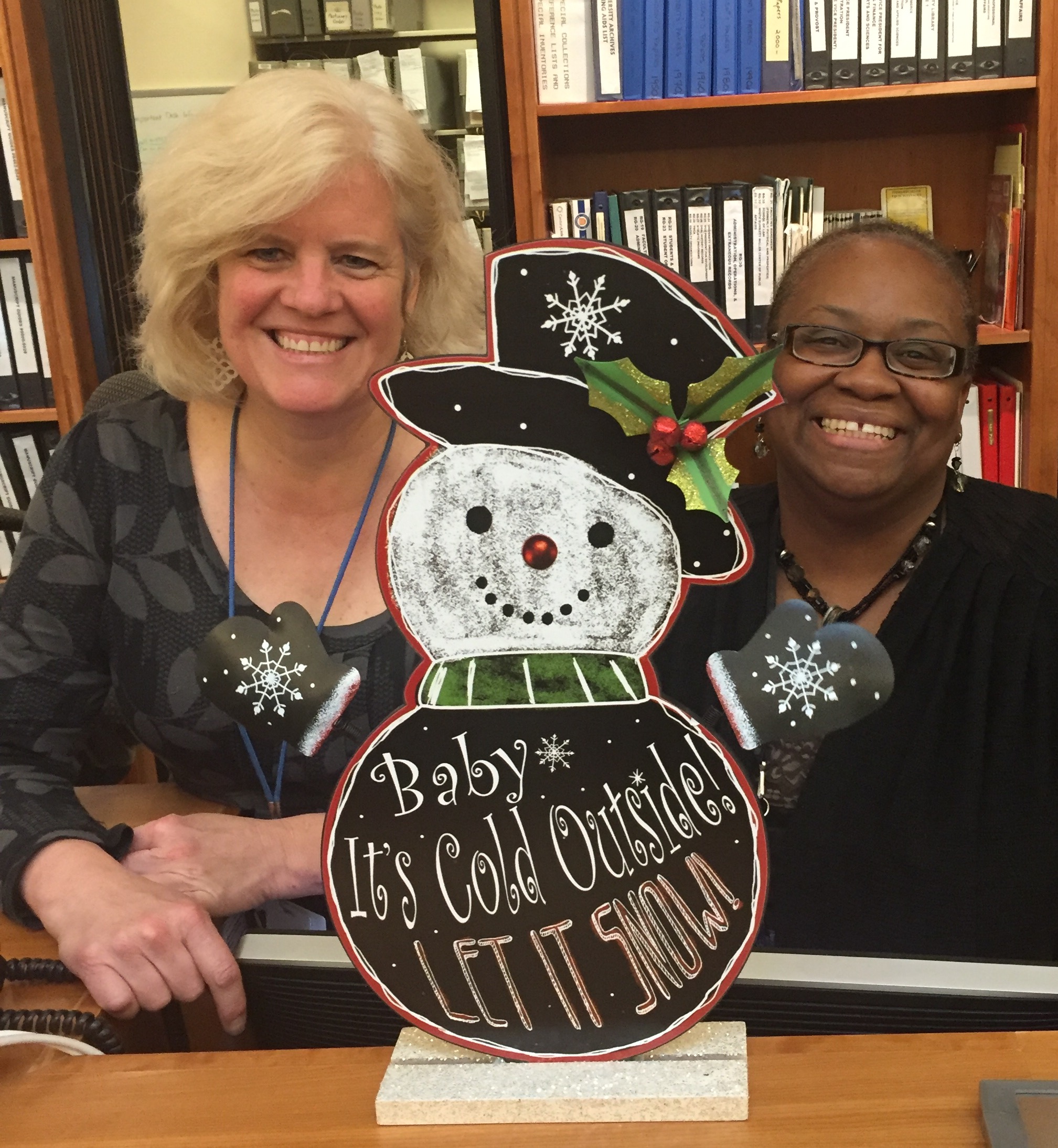

Regina, at right, with fellow snow fan and Reference Coordinator Anne Causey. They both wish that the claim made on this Reading Room holiday decoration was TRUE!

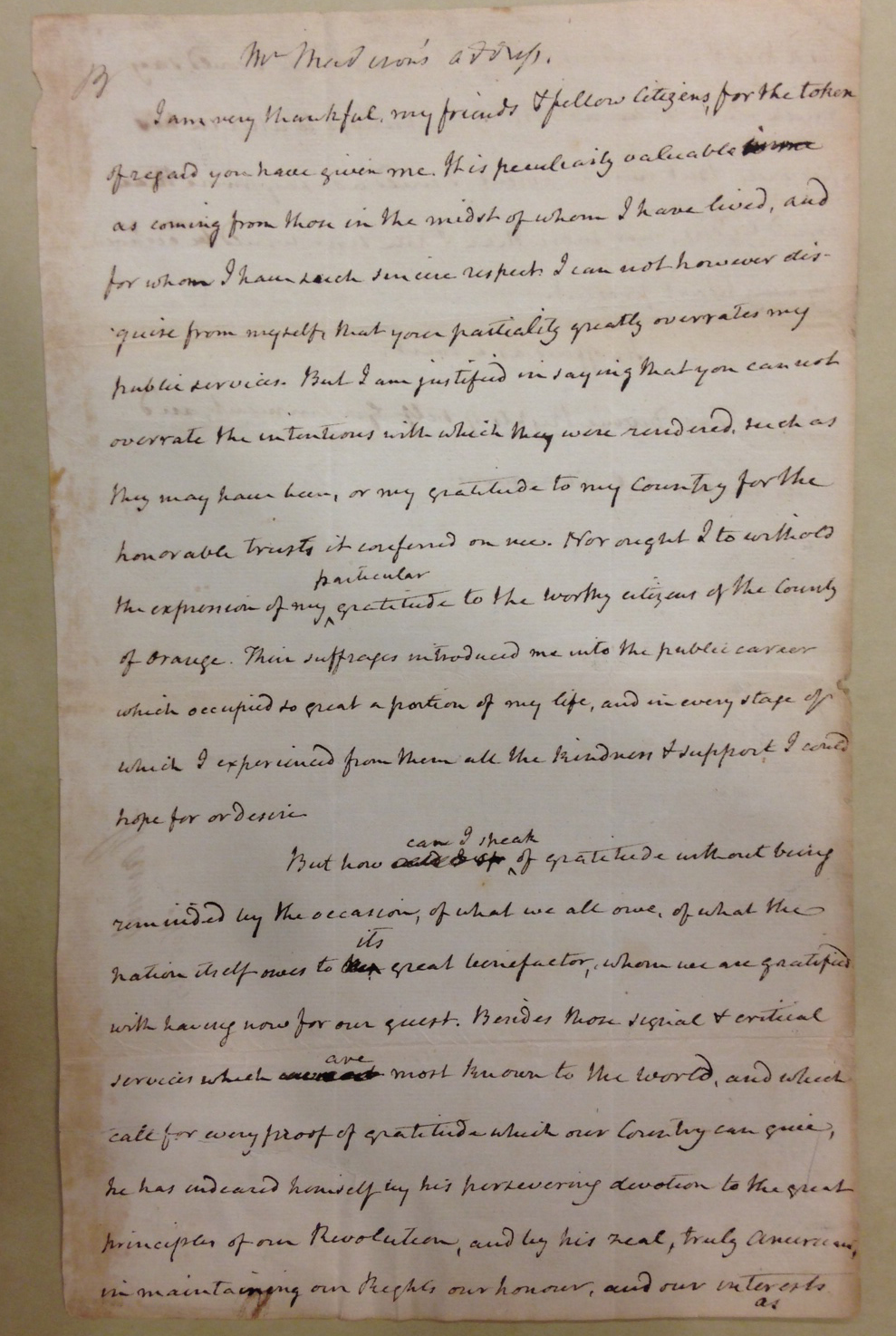

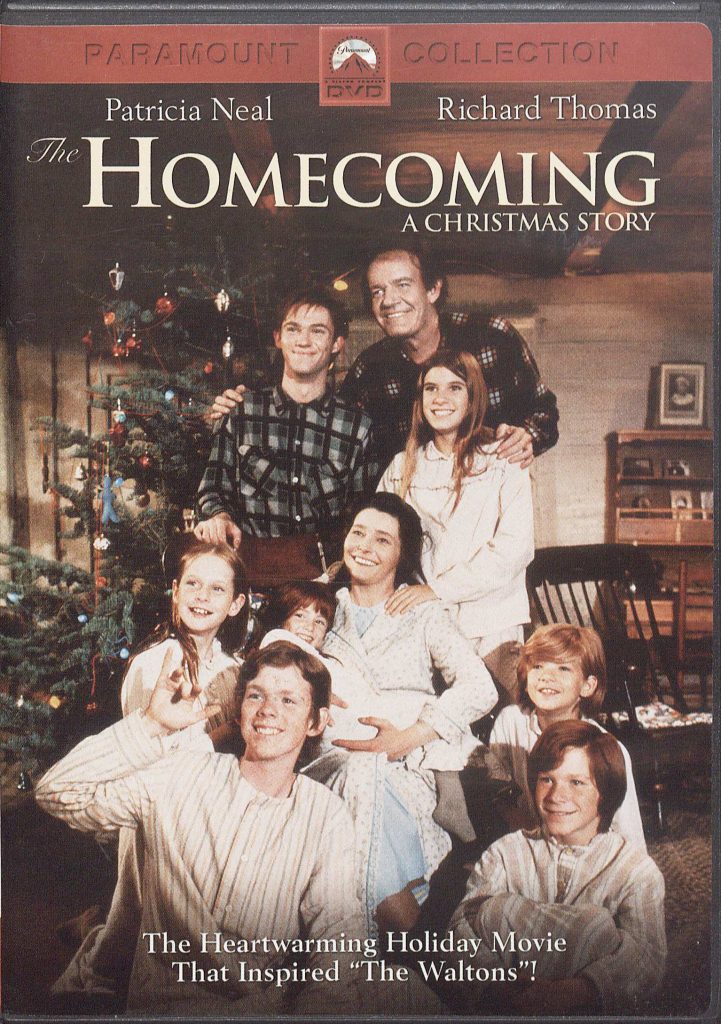

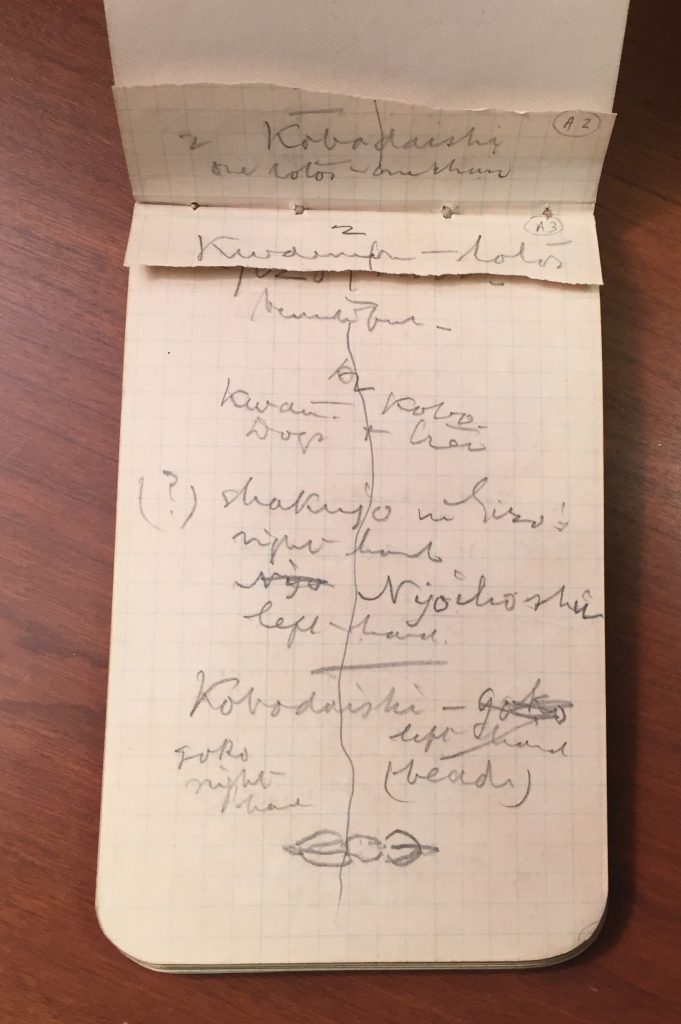

Shortly after I began looking into the Small Library’s treasure troves, I was delighted to discover that we hold a small but rich collection of Virginia native Earl Hamner Jr., an Emmy-winning television writer and director during the 1970’s and 80’s. The collection includes a first edition of Hamner’s 1970 novel, The Homecoming: A Novel about Spencer’s Mountain, the final shooting script for the 1971 film The Homecoming: A Christmas Story and television scripts for three mid-1970s episodes of The Waltons.

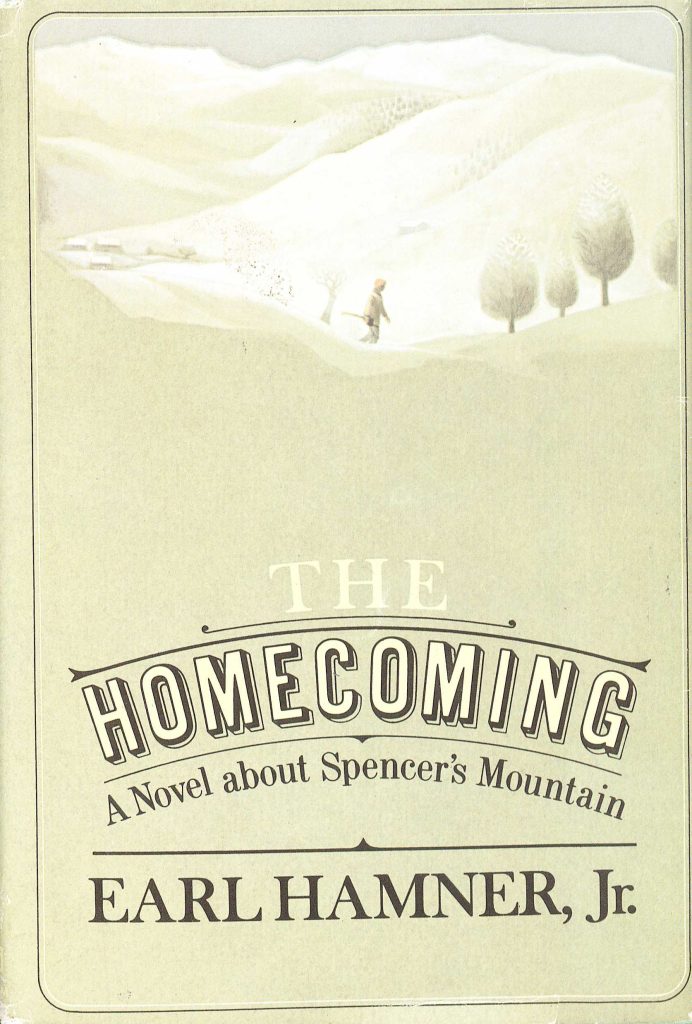

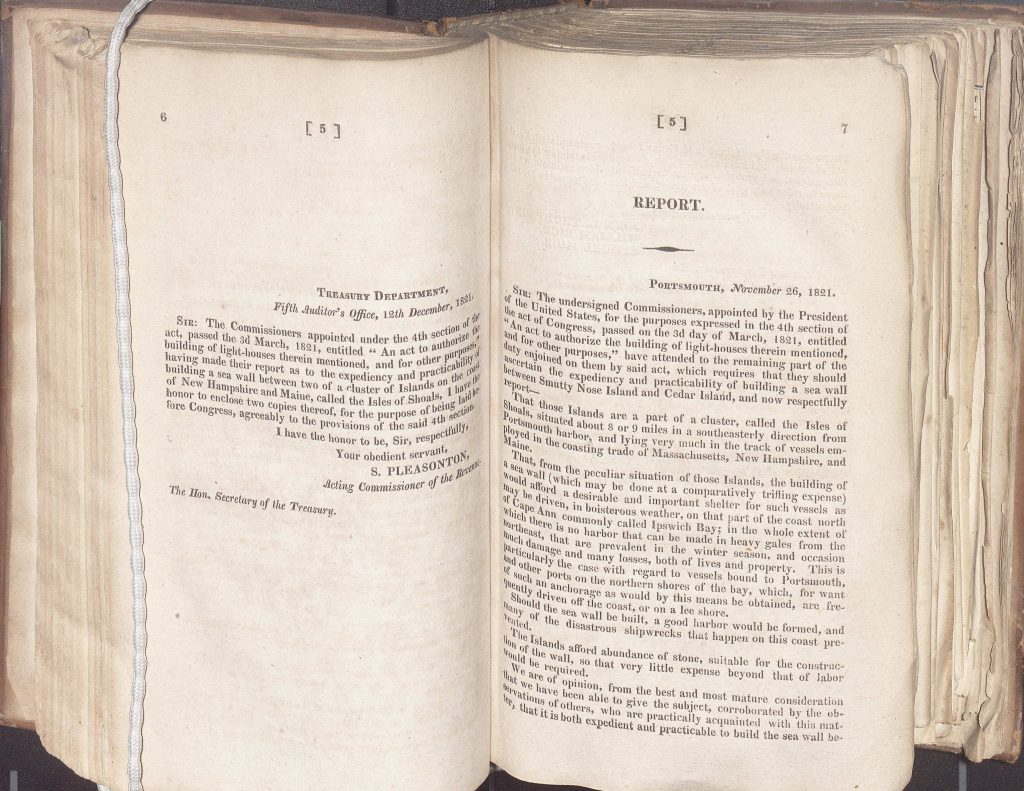

Earl Hamner, Jr. The Homecoming: A Novel about Spencer’s Mountain. (PS3558 .A456 H6 1970). The novel’s epigraph reads, “It is remembered in my family that Christmas Eve of 1933 my father was late arriving home. That, along with the love he and my mother bestowed upon their eight red-headed offspring, is fact. The rest is fiction.”

The novel, drawn from Hamner’s childhood experiences growing up in Schuyler, Virginia during the Great Depression, was the impetus for the film. Originally aired on CBS on December 19, 1971, the movie was so popular that it spun off a series, “The Waltons’, which aired on CBS in September 1972 and became wildly popular, lasting nine seasons.

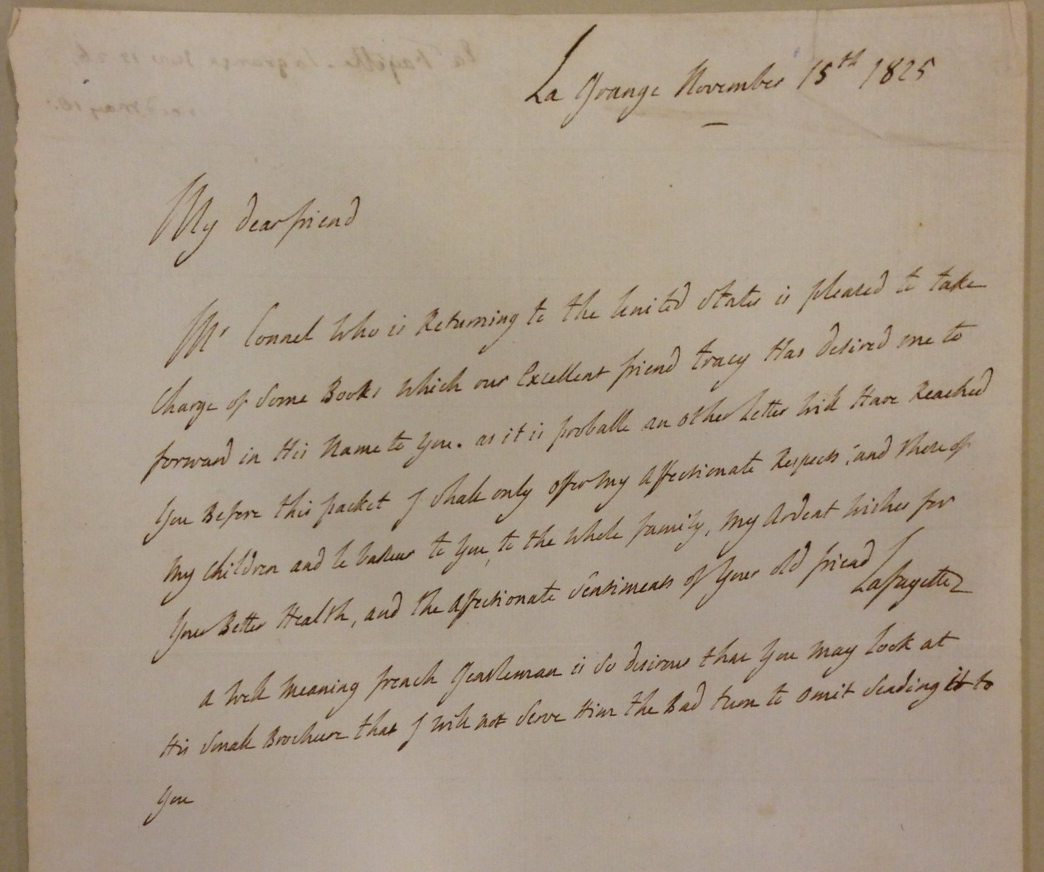

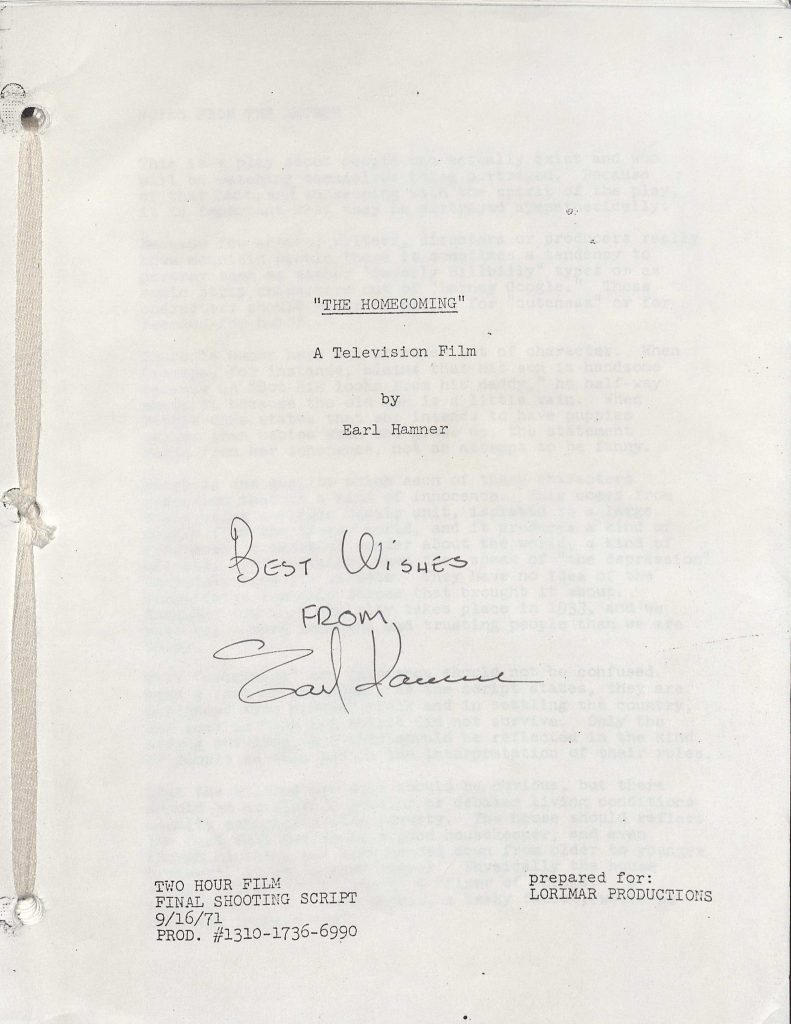

Cover of the Final Shooting Script for the Lorimar Productions film “The Homecoming” (MSS 10380,-a,-b)

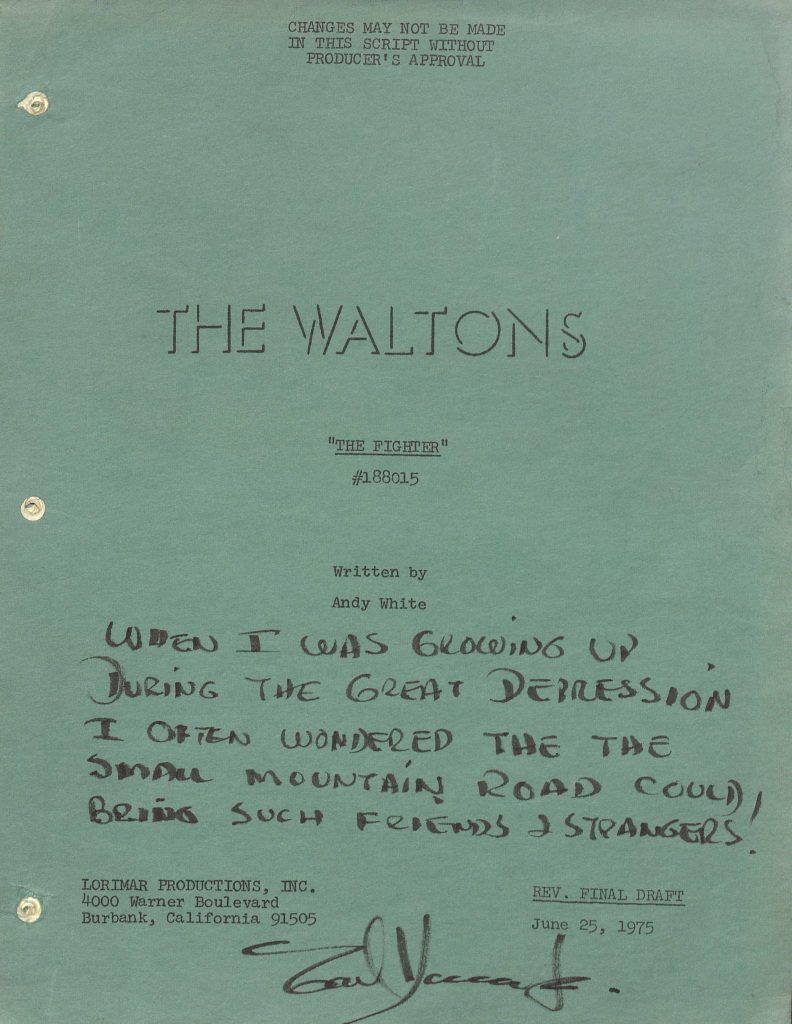

Cover of the television script for an episode of “The Waltons.” This is the revised final draft of episode #188015, “The Fighter” by Andy White (MSS 10380,-a,-b)

Christmas fans like myself know that the film that started the Waltons’ phenomenon is a holiday must-see. Included in the final script of the 1971 film ‘The Homecoming’ is a section entitled “Notes from the Author”:

[The] Christmas Season and Christmas has become a nightmare for most people. The packed stores, the enraged crowds, the stalled traffic and money worries that are common to our audience for the most part produce a national insanity. Yet underneath there is a pathetic wish that they can really experience something, maybe “The Christmas Spirit” something that no other time provides.

This holiday classic is a great start toward achieving that “Something.” So, shut out the madness of the holiday hustle and bustle. Pour yourself a BIG glass of egg-nog, get comfortable in your favorite chair and lose yourself in this wonderful coming-of-age Christmas classic. By the film’s end, I guarantee you will feel all warm and fuzzy inside (though that BIG glass of rum-infused egg nog may be partly responsible!). Wishing my colleagues and all the loyal readers of ‘Notes from Under Grounds’ a very safe and happy Holiday!

“Good Night, Penny”

“Good Night, Edward”

Good Night, David”

“Good Night, Heather and Gayle”

“Good Night George, Petrina, and Molly”

“Good Night E.J., Sharon, Ellen, Barbara, Jane…………”

Good Night, “Notes from Under Grounds” Readers!

![Joseph Hutchings purchased 8 volumes of of Shakespeare "for [his] self" (MSS 467).](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/theobalds_shakespeare.jpg)