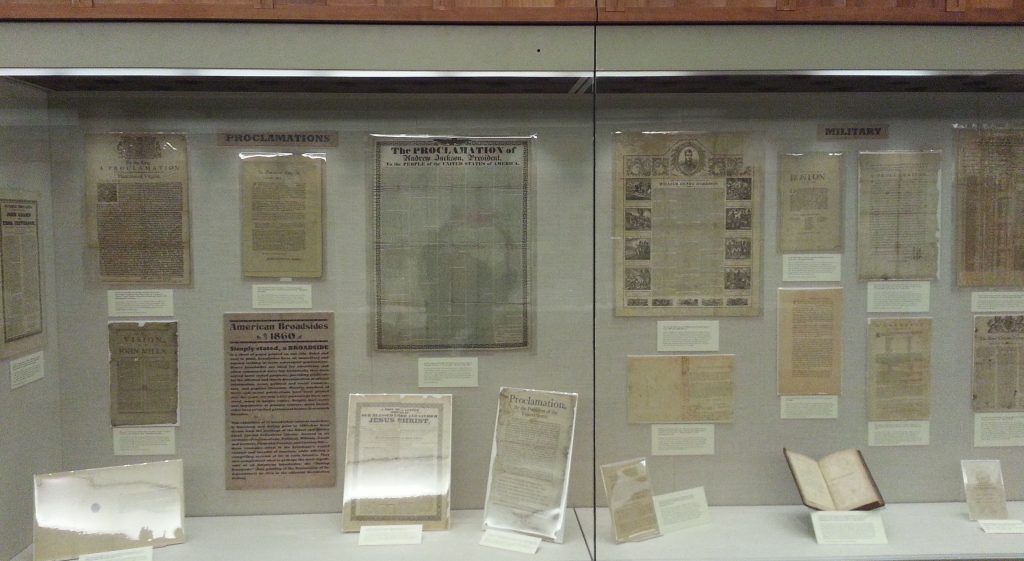

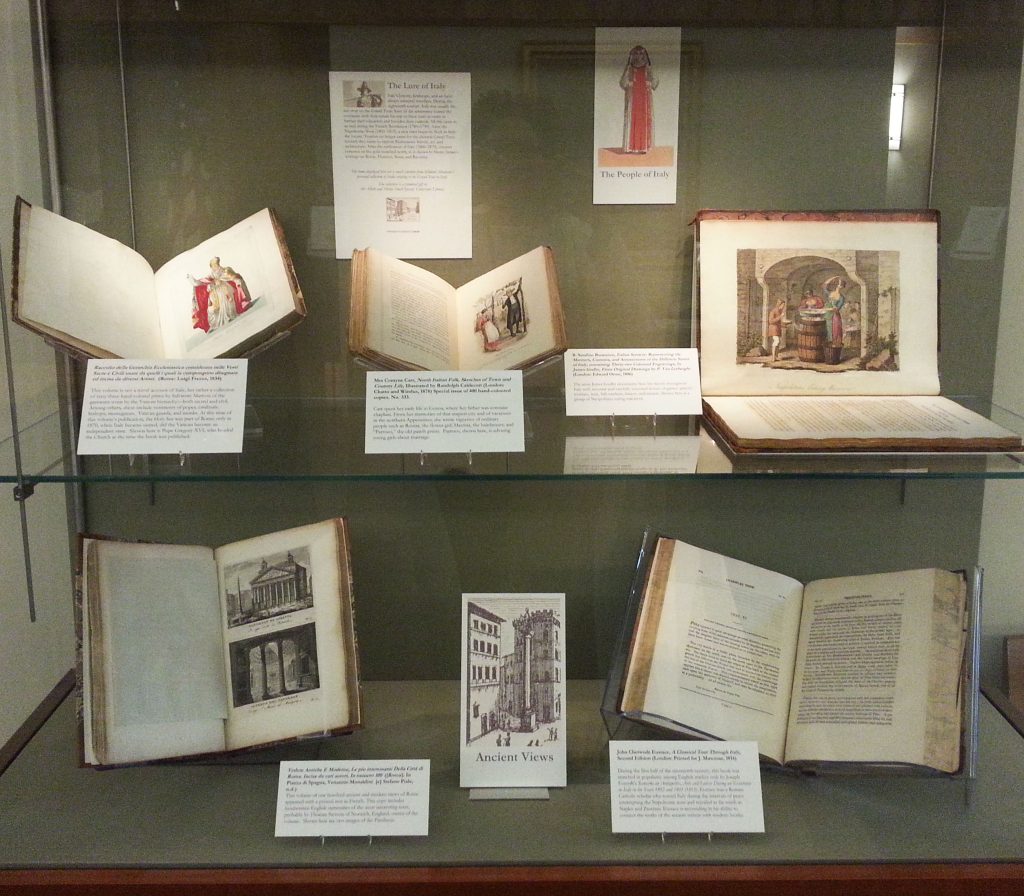

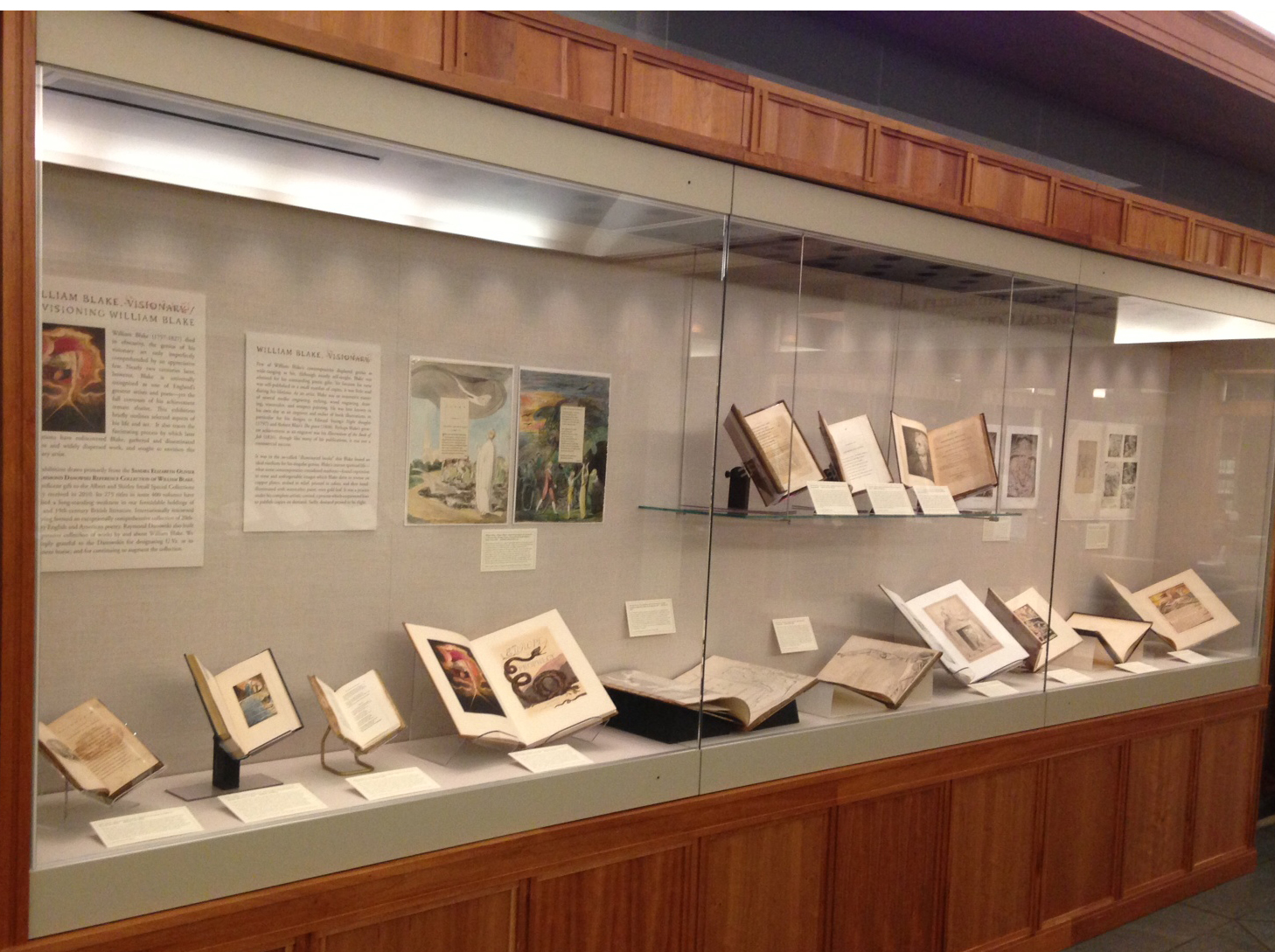

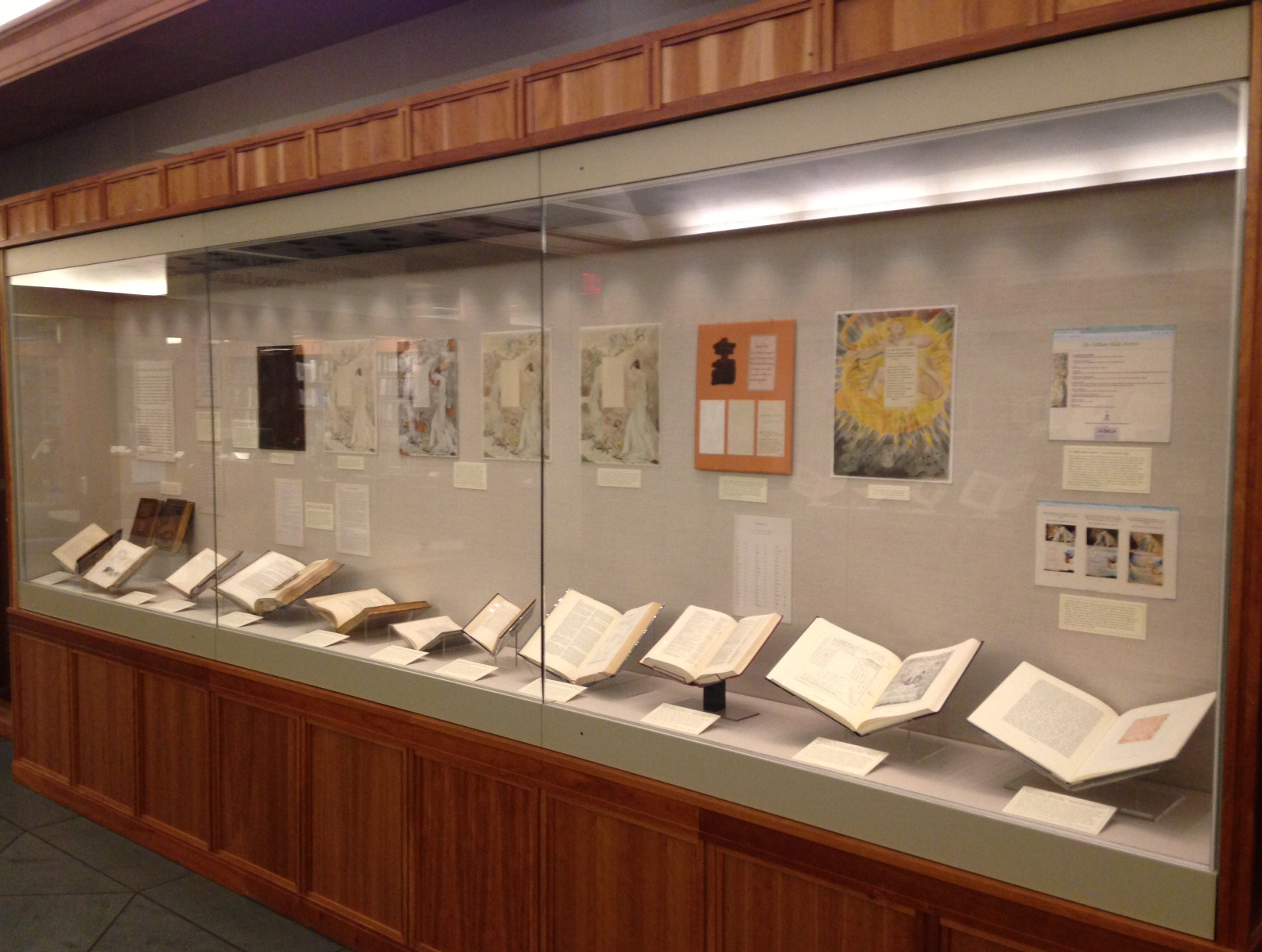

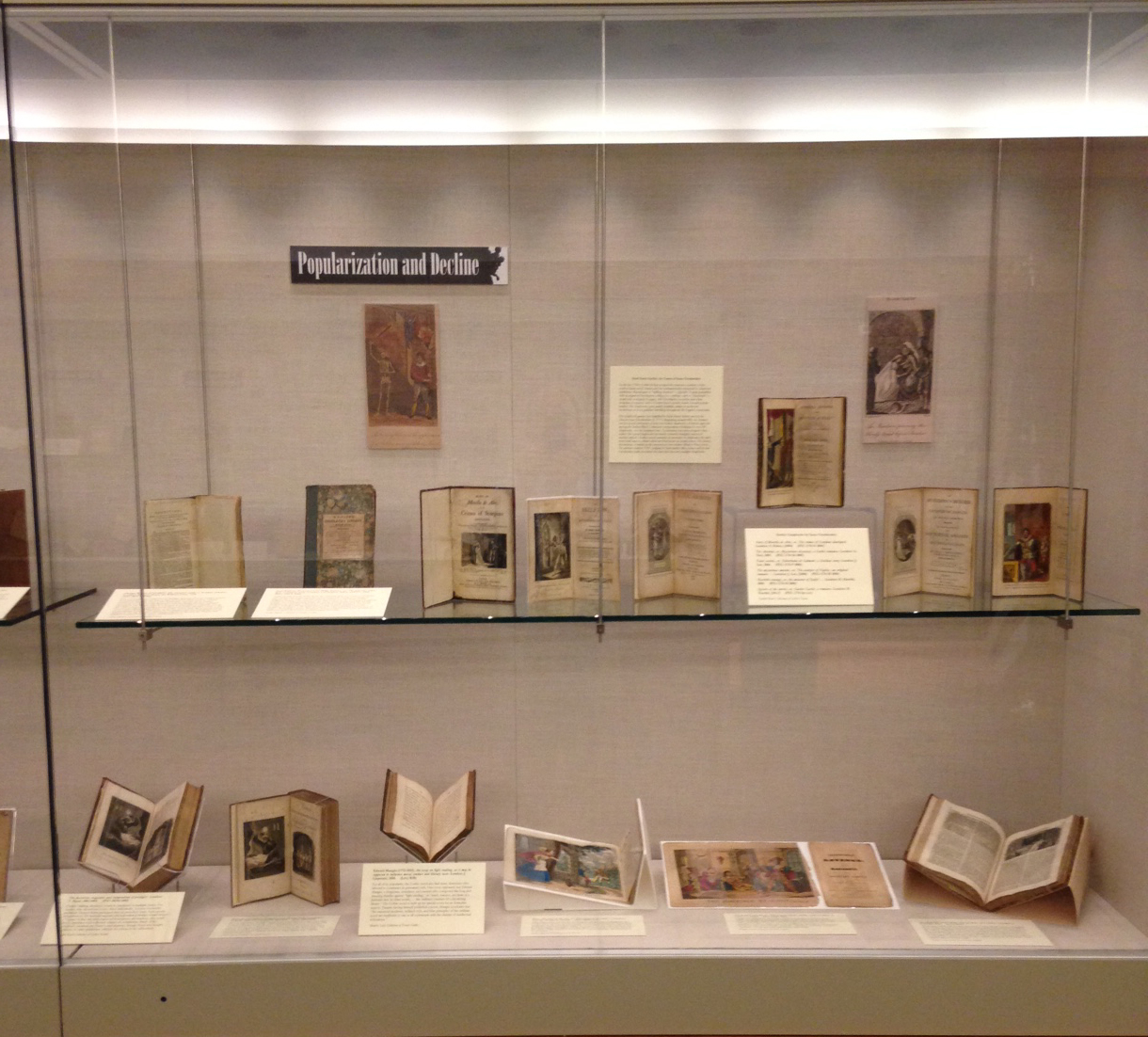

A portion of the exhibition, “Fearsome Ink: The English Gothic Novel to 1830,” on view through May 28.

Some readers will know that the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library possesses what is considered the world’s finest collection of English Gothic novels. From approximately 1765 to 1830 English readers eagerly embraced a new genre of “Gothic” fiction: typically set in medieval times, imbued with Gothic sensibilities, and frequently invoking the supernatural, its passionate and vividly delineated characters endured untold horrors of the imagination and scourges of the flesh. Ever since, this profusion of what one might term “fearsome ink” has profoundly influenced the world’s literary and popular culture.

A Gothic precursor and Shakespeare source: Matteo Bandello’s tale of the ill-fated lovers of Verona, Romeo and Juliet, in French translation. Matteo Bandello, Histoires tragiques. Paris: Gilles Robinot, 1559. (Gordon 1559 .B3)

The nucleus of U.Va.’s collection was formed by British bibliographer Michael Sadleir and enlarged by U.Va. graduate student Robert K. Black, who donated the Sadleir-Black Collection of Gothic Fiction to U.Va. in 1942. Since then the collection has grown steadily through purchase and gift. In 2012 the French scholar Maurice Lévy—who five decades earlier had mined the Sadleir-Black Collection for his dissertation—generously gave to U.Va. a superb collection of Gothic fiction in French translation: the Maurice Lévy Collection of French Gothic. Highlights from these two collections are now on view in the exhibition “Fearsome Ink: the English Gothic Novel to 1830.”

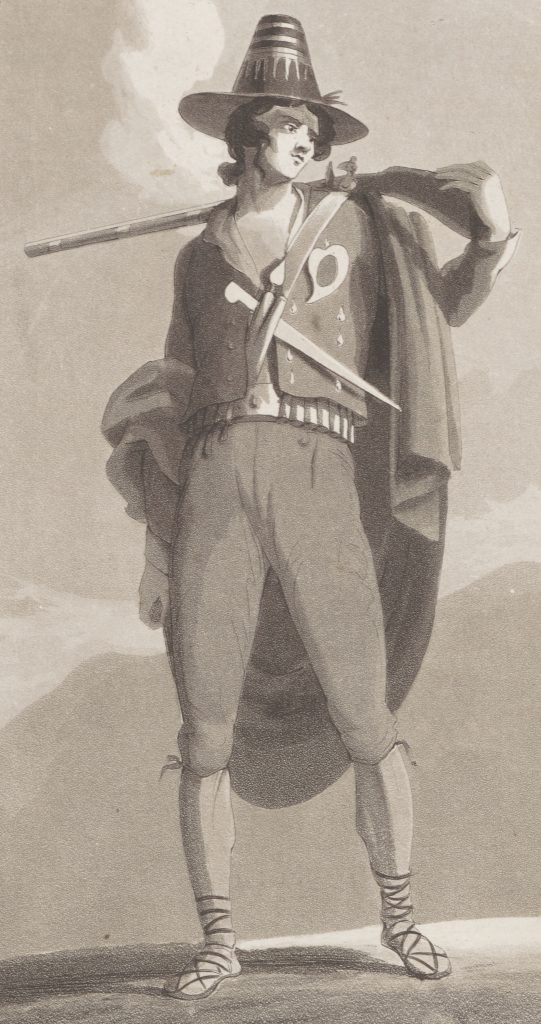

Oh, the horror! A hand-colored, engraved frontispiece to an early 19th-century “shilling shocker,” or chapbook adaptation of a Gothic novel.

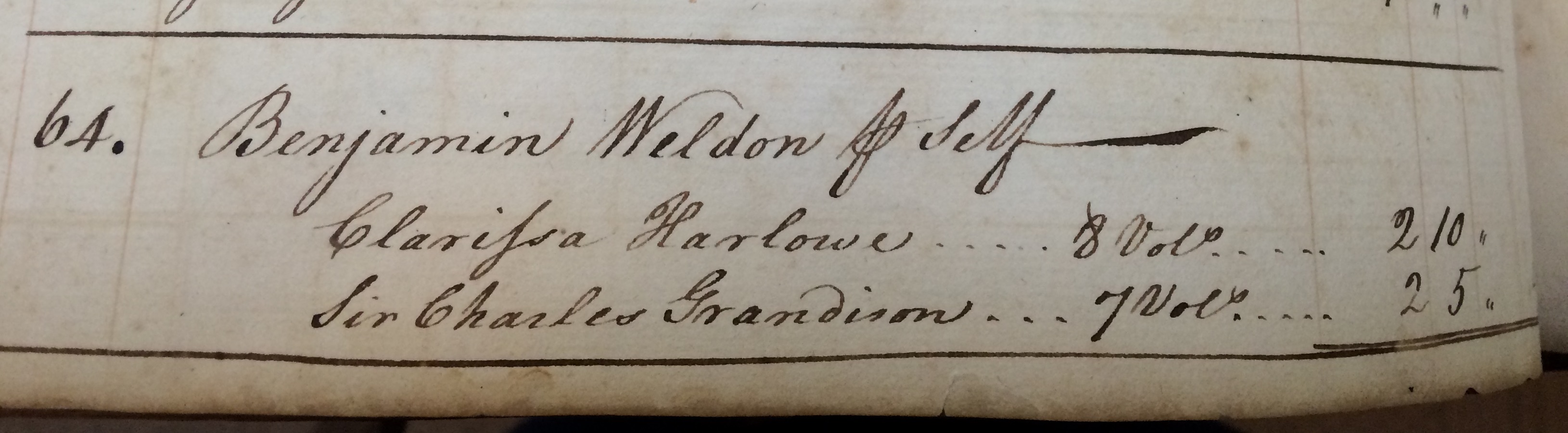

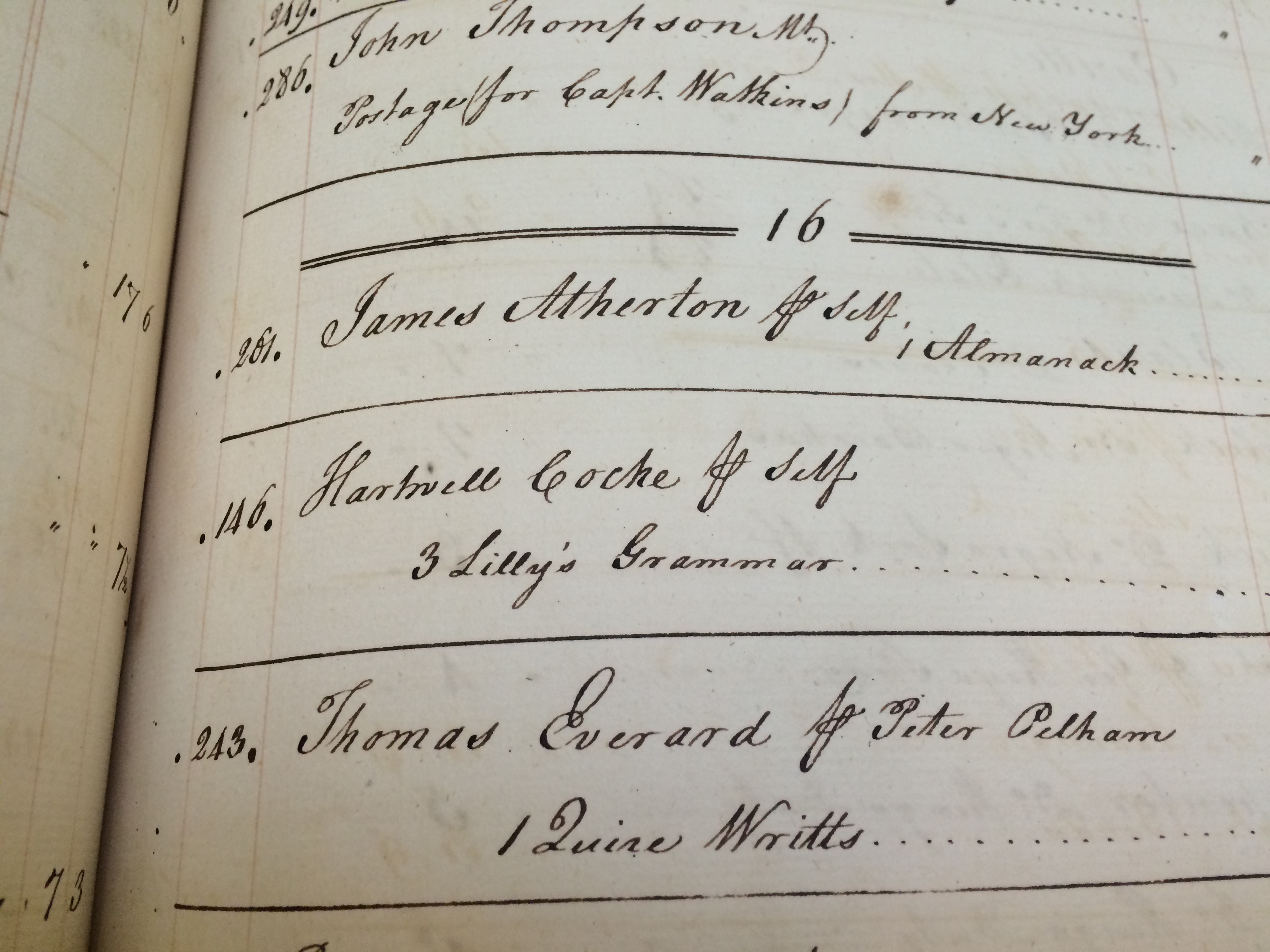

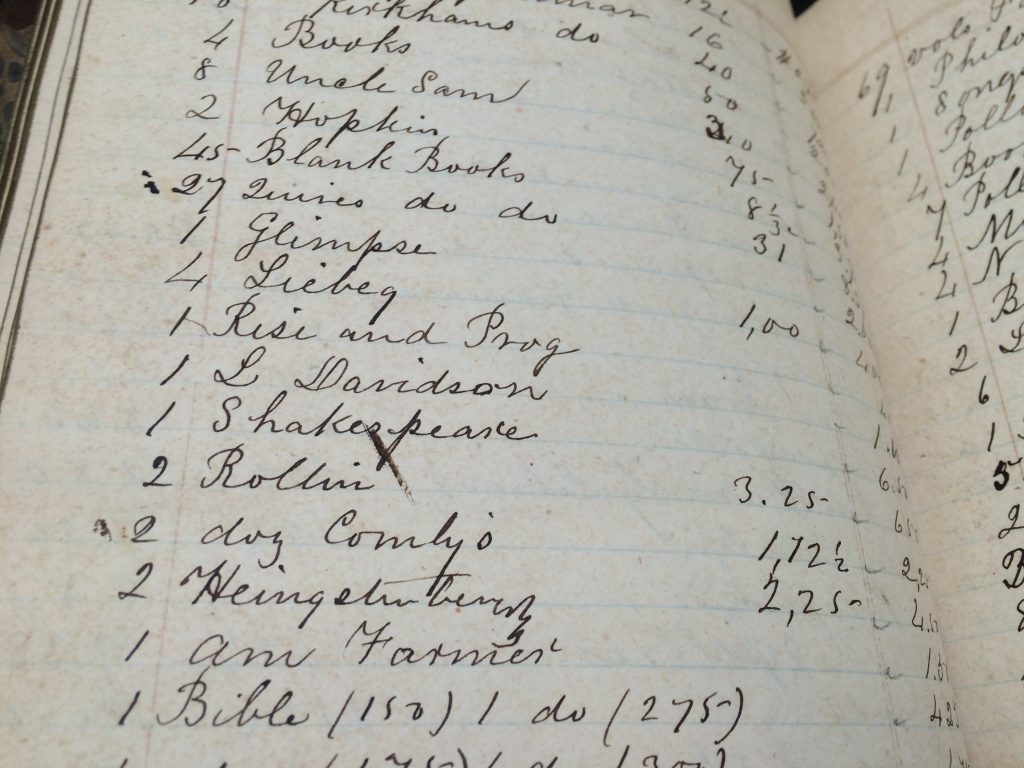

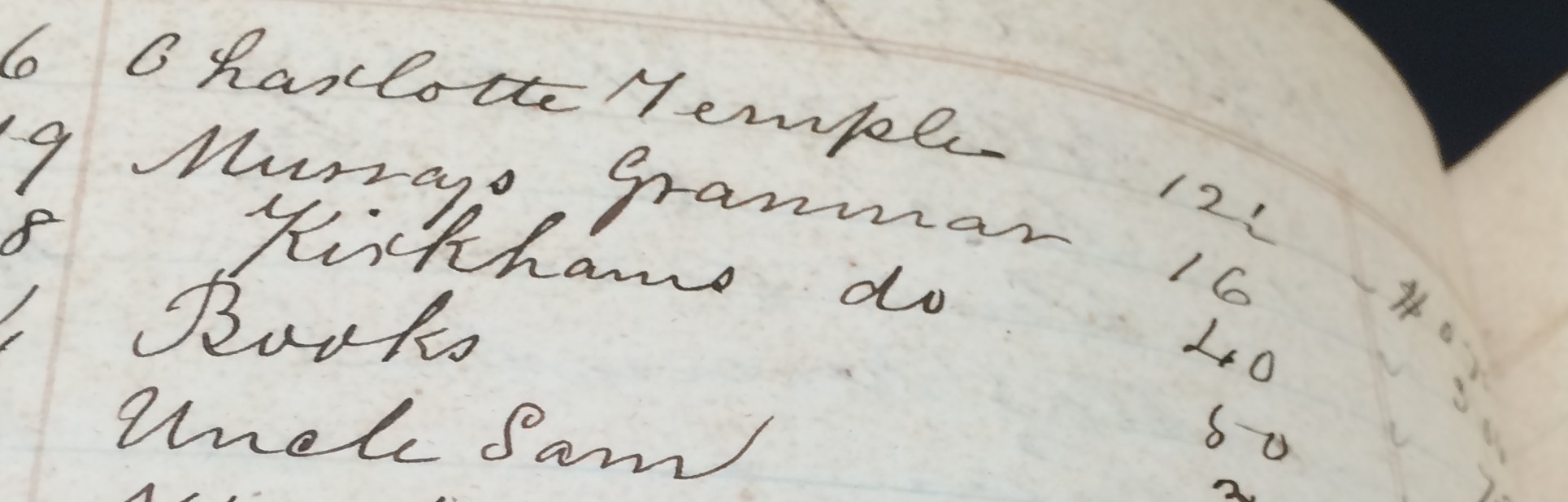

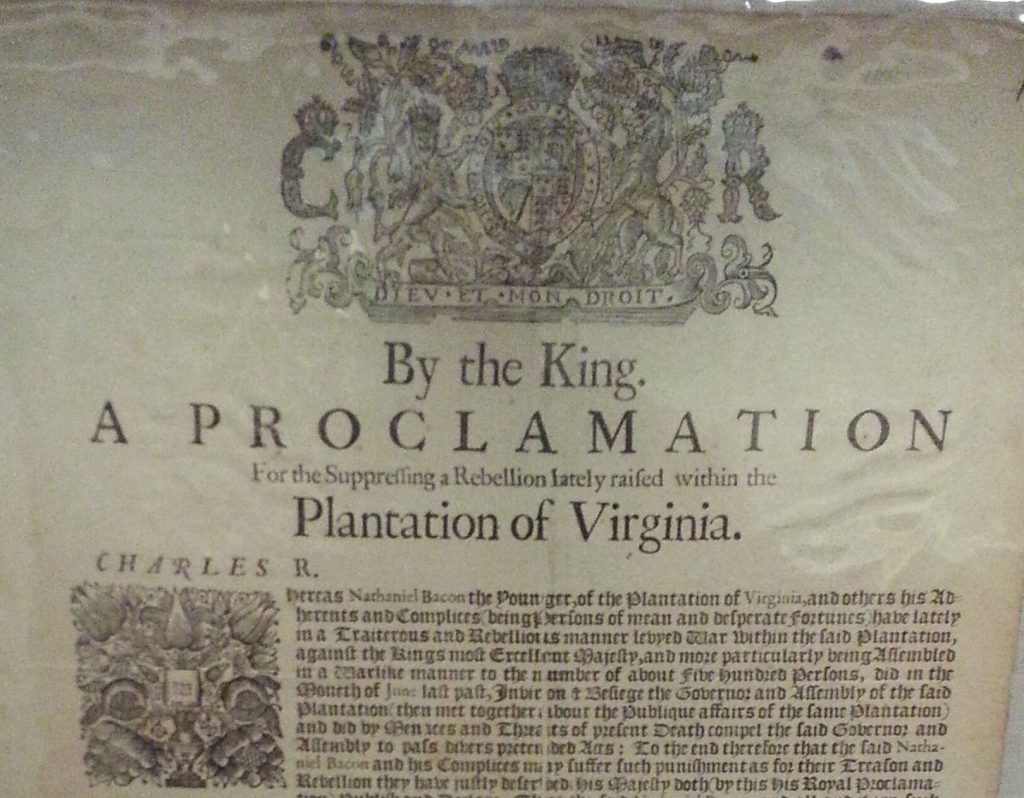

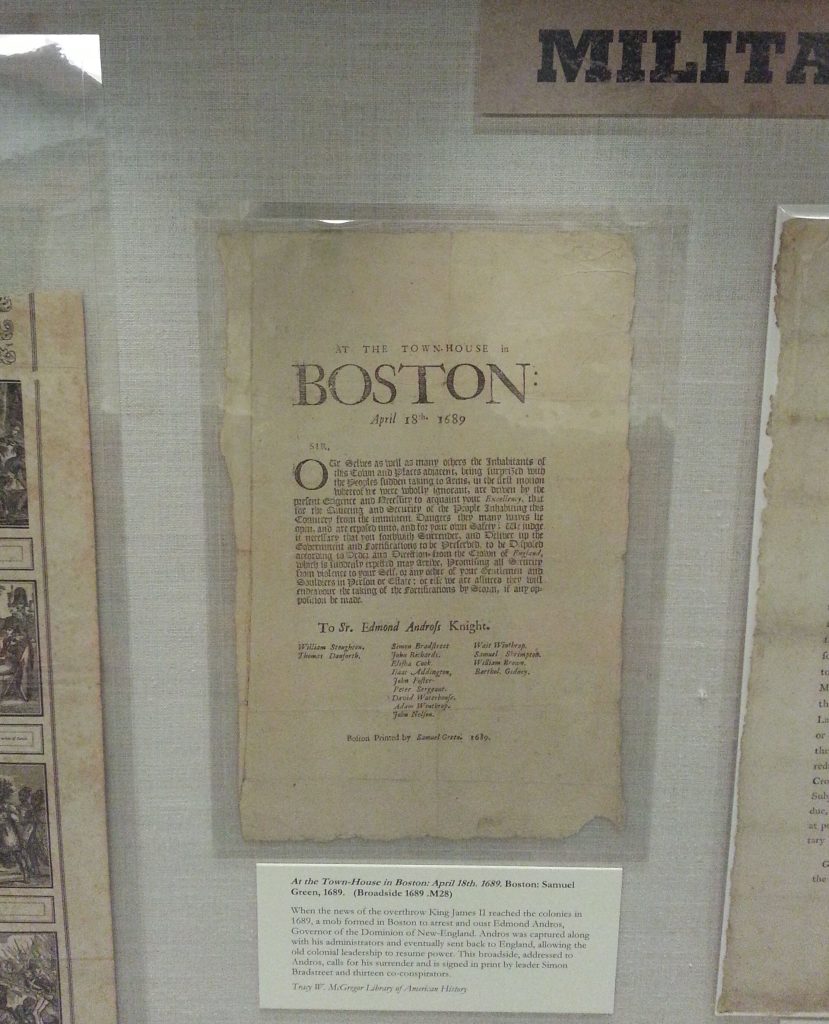

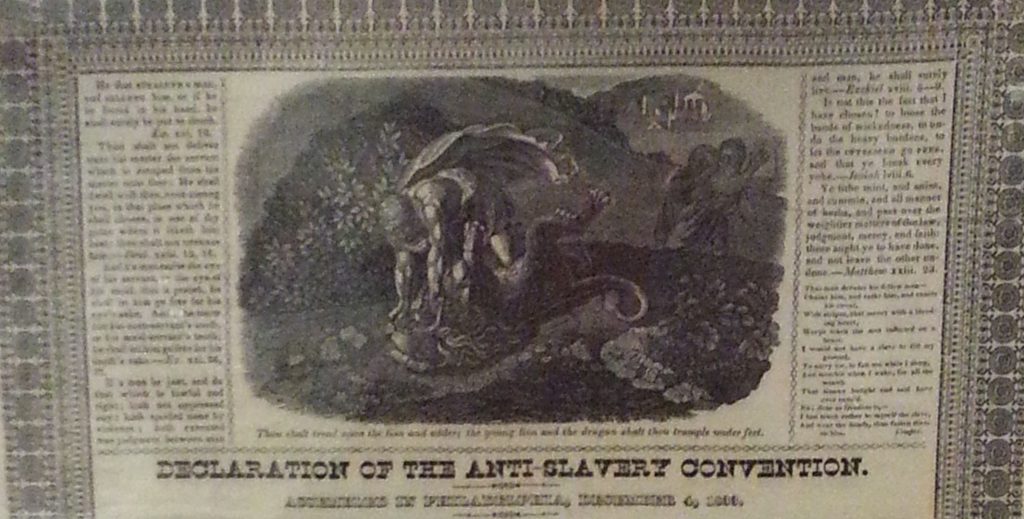

“Fearsome Ink” explores the English Gothic novel as a publishing phenomenon as well as a literary genre. It seeks to situate the English Gothic novel in international context; probe its potential for research in such areas as literary history, the history of publishing and reading, and book illustration; and profile the collectors responsible for building U.Va.’s magisterial holdings. Highlights include 16th– and 17th-century precursors of Gothic literature; contemporary German “shudder novels”; French translations of English Gothic novels; early American attempts to write Gothic fiction suited to American audiences; parodies of Gothic fiction; strikingly illustrated popular chapbook versions of Gothic novels; copies owned (and presumably read) by “persons of quality”; and battered circulating library copies read by the majority of contemporary readers.

Original manuscript contract, signed by Ann Radcliffe, for her bestselling novel, The Mysteries of Udolpho (London: G.G. and J. Robinson, 1794). Radcliffe’s novel commanded the princely sum of 500 British pounds from publisher George Robinson. (MSS 1625)

On March 25-26, U.Va.’s Department of French is sponsoring a related conference, “The Dark Thread: From histoires tragiques to Gothic Tales.”

“Fearsome Ink” will remain on view through May 28 in the first floor gallery of the Small Special Collections Library.

“Fearsome Ink” will remain on view through May 28 in the first floor gallery of the Small Special Collections Library.

![Joseph Hutchings purchased 8 volumes of of Shakespeare "for [his] self" (MSS 467).](https://smallnotes.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/theobalds_shakespeare.jpg)