This week we are pleased to feature a guest post by curatorial student assistant Elizabeth Ott, who has written an in-depth account of just one of the many wonderful books in our recently acquired Hobo Collection. Hats off to rare book cataloger Gayle Cooper, who brought to our attention the discrepancy between the two copies discussed here.

Visitors to the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library may find themselves pricking up their ears to catch the far-off, lonesome whistle of a nighttime freight train. The occasion for these phantom whispers is the recent acquisition of the Hobo Collection, comprising 73 books and approximately 40 items of ephemera related to vagrancy, tramping, migrant workers, and hobo life in nineteenth and twentieth-century America.

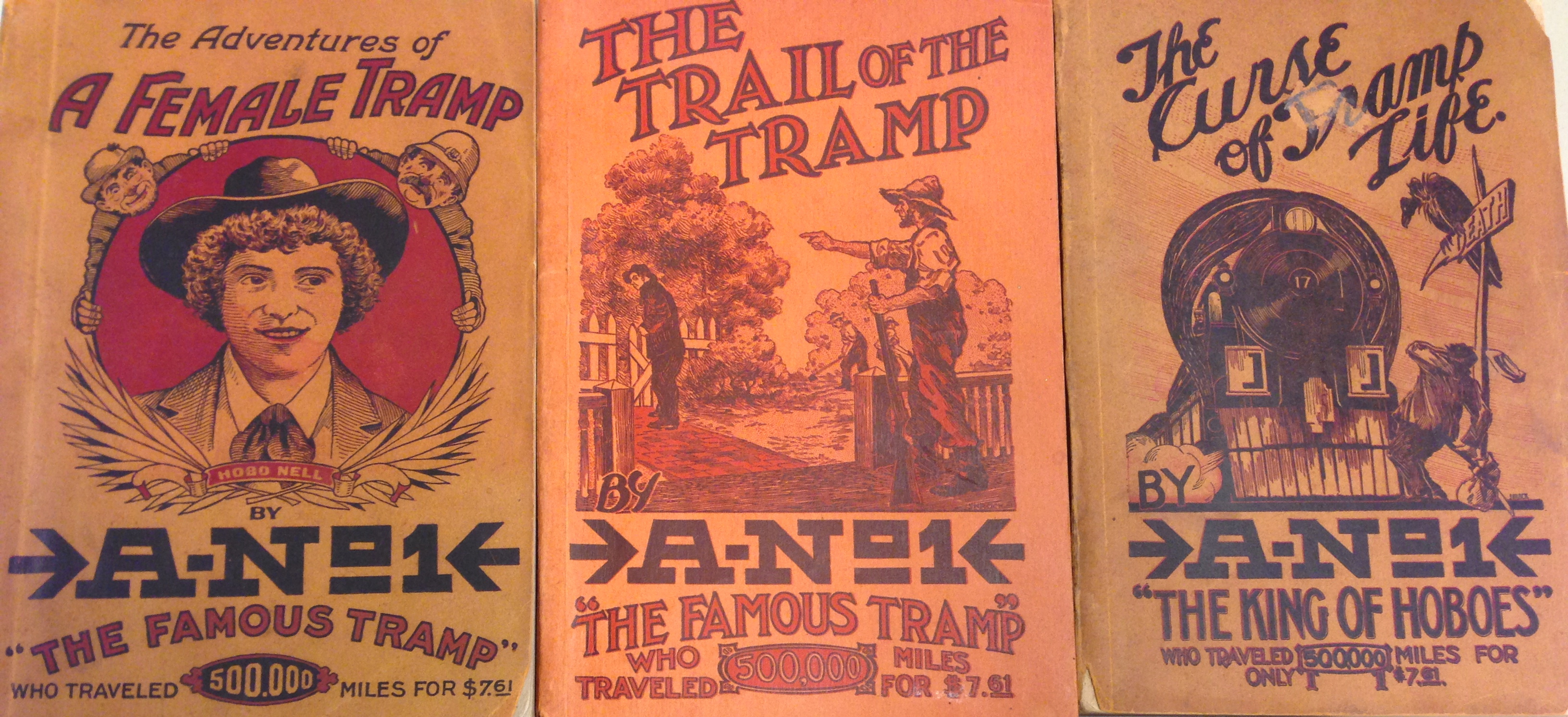

The collection spans more than 150 years and includes fiction, autobiography, pamphlets, periodicals, photographs, songbooks, and even cookbooks. Some of the highlights of the collection include early issues of the Hobo News, a first edition of Woody Guthrie’s fictionalized autobiography Bound for Glory (1943), and a run of the “A-no.1” series written by famous hobo “Rambler” Leon Ray Livingston.

Three issues of the A-No.1 series of tales of hobo life (HV 4505 .L58 B66, Associates Endowment Fund. Photo by Elizabeth Ott)

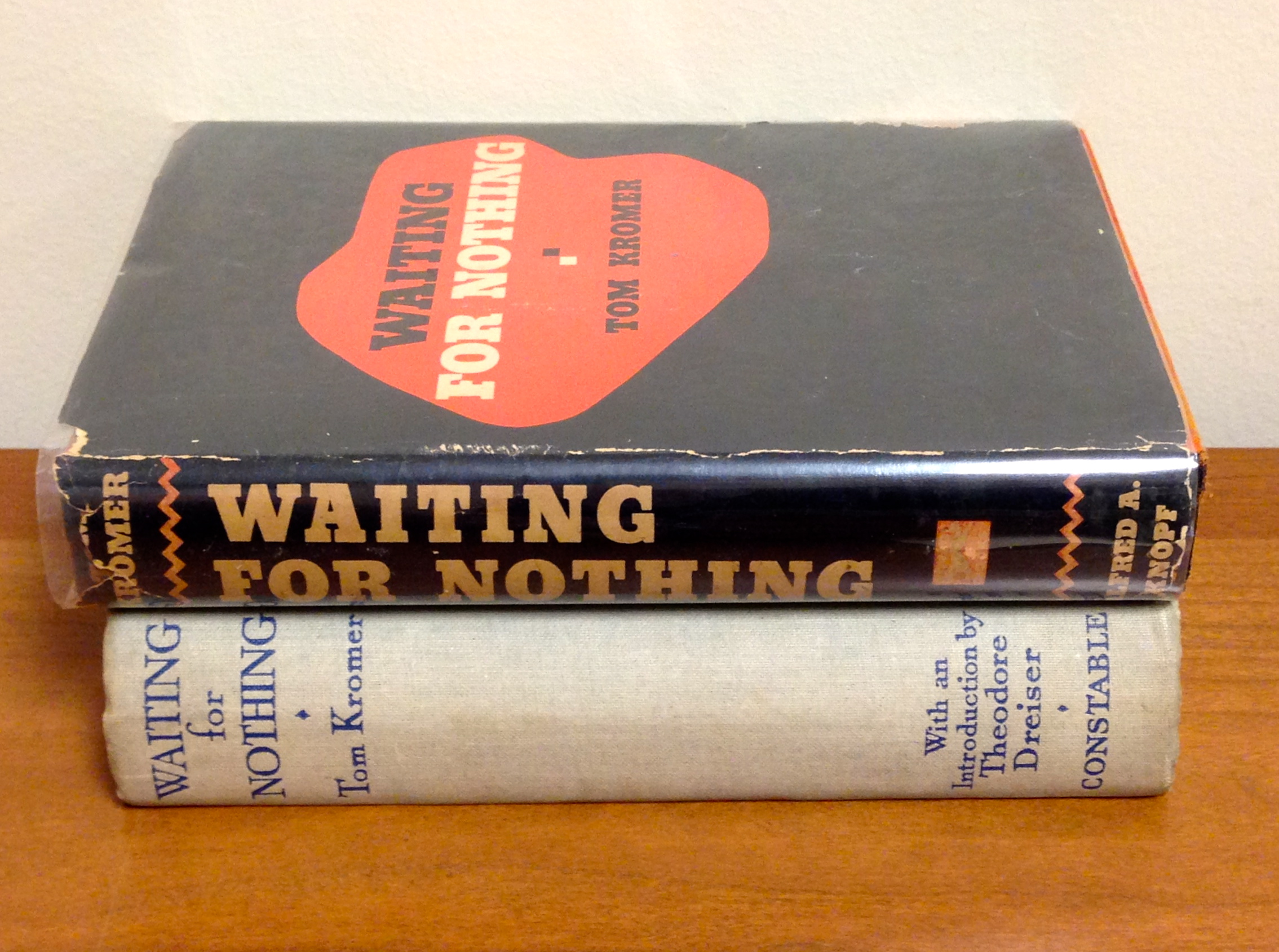

Among the many noteworthy items in this rich collection is a copy of the first American edition of West Virginia writer Tom Kromer’s 1935 novel-memoir Waiting for Nothing. Though never a runaway bestseller, Kromer’s hardboiled account of his years as a migrant laborer and itinerant bum was widely lauded for presenting a compelling and unsentimental portrait of hobo life during the Great Depression. Kromer wrote the bulk of the novel in 1933 while working for the Civilian Conservation Corps at Camp Murphy in Jupiter, Florida. He initially struggled to interest a publisher in his manuscript, but gained the attention of the prominent journalist Lincoln Steffens, who encouraged him to pursue Max Lieber as a literary agent. Lieber quickly secured Alfred A. Knopf as publisher.

Kromer became something of a critical darling. His clipped style and aggressive use of slang gained him a reputation as a street-smart Hemingway. Among those who championed the novel was Theodore Dreiser, whose novels Sister Carrie and Jennie Gerhardt, amongst others, explore similar themes of poverty, labor, and class relations. Dreiser was so taken with Kromer’s tale that he convinced his British publisher, Constable & Co., to undertake a British edition and agreed to write an introduction for it.

For many years, this British edition has been the only copy of Waiting for Nothing in Special Collections at U.Va. because of its association with Dreiser, a writer heavily represented in the Barrett Library of American Literature. Now that it is joined by its American counterpart, researchers will have a much more complete picture of the novel’s cultural significance. For while the American edition lacks the preface written by Dreiser, the British edition lacks the book’s entire fourth chapter.

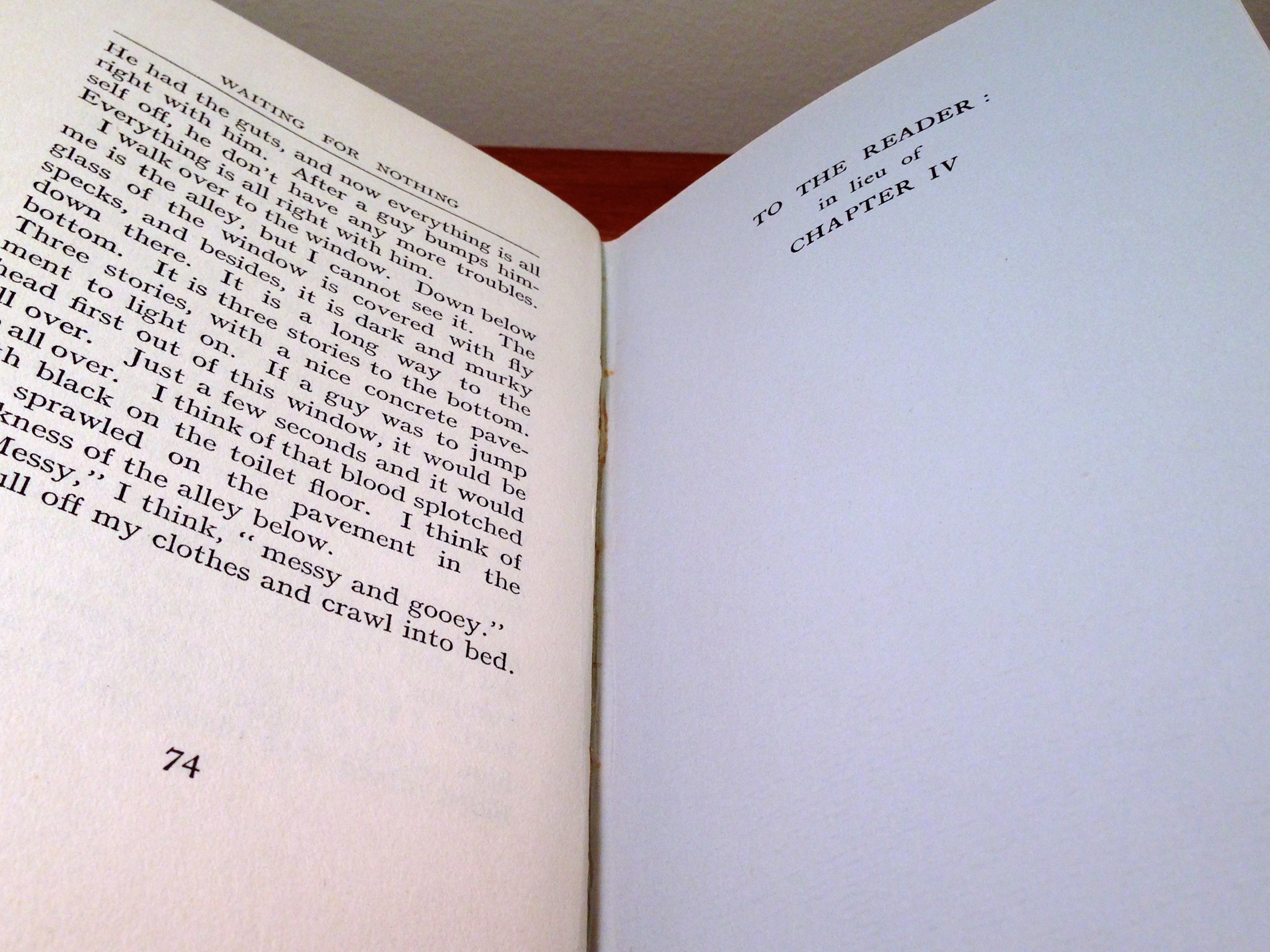

The page opening where chapter 4 is meant to appear in the first British printing of Waiting for Nothing (PS 3507 .R55 A165 .K7 1935, Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature, Theodore Dreiser Collection. Photograph by Elizabeth Ott).

Where the fourth chapter should appear in its pages is instead an eight-page insert about the nature of censorship on blue paper titled “To the Reader: in lieu of Chapter IV.” The decision to replace chapter four seems to have been last minute, as described in the appendix of to a 1977 scholarly edition of the novel:

Constable originally seems to have seen nothing especially objectionable in this fourth chapter; the text was typeset and printed with the other chapters in the first impression. Bibliographical evidence indicates that the sheets of this impression were folded and ready for stitching and binding when Constable decided not to risk publication of chapter 4. Pages 75-94 of the unstitched gatherings (all of chapter 4) were cancelled—that is, were razored out—and in their place was inserted an eight-page gathering…

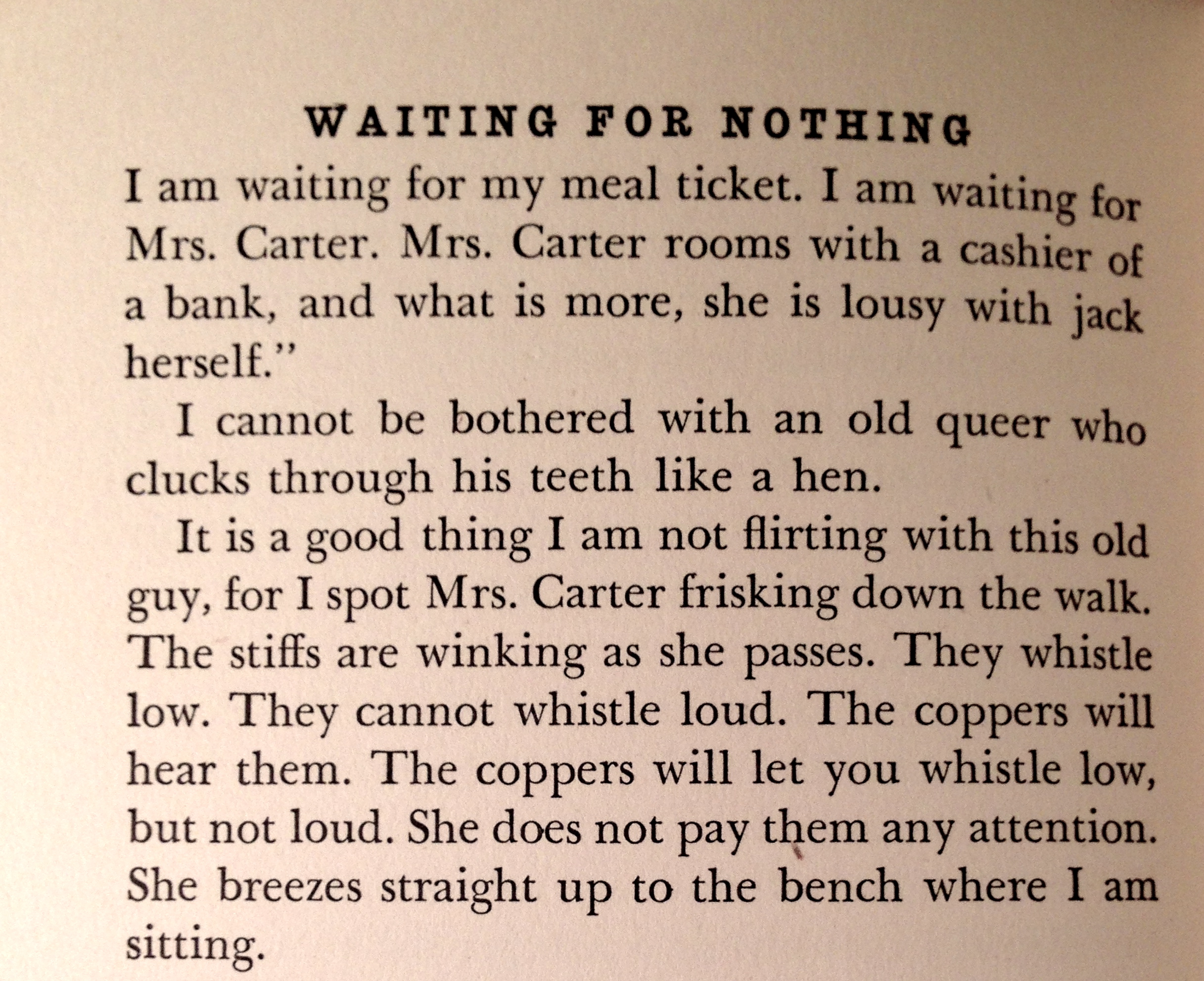

Our newly acquired American edition allows us to finally get a peek at what salacious happenings occur in this objectionable fourth chapter:

“How do you eat?”

He knows how I eat, but we are playing a game.

The selling point of Waiting for Nothing is that it illuminates the unsavory aspects of tramping—desperate men, degenerate women, seedy flophouses and near escapes from brutal coppers—without appearing sensational. It’s tricky to strike this balance; the material must contain calculated shocks without tipping over into sentiment and all the while the narrator must remain sympathetic, above the dirt and grime even as he wades through it.

A passage from chapter 4, which appear in full in the American edition of Waiting for Nothing (PS 3521 .R57 W3 1935, Associates Endowment Fund. Photograph by Elizabeth Ott).

Nowhere is this tenuous balance more on display than in the controversial Chapter Four, where Kromer meets and “makes” a transgendered woman, Mrs. Carter, in a park. Kromer flirts with her and obtains money to buy dinner, repeatedly reminding the reader that “we are playing a game.” The two agree to meet later to go to a show together, though we are to understand that the real arrangement is that payment for the meal will be sex. The chapter ends with the fulfillment of this promise: “You can always depend on a stiff having to pay for what he gets. I pull off my clothes and crawl into bed.”

The balance of Kromer’s matter-of-fact admission of prostitution is his insistence on his own revulsion: “A pansy like this, with his plucked eyebrows and his rouged lips, is like a snake to me. I am afraid of him. Why I am afraid of this fruit with his spindly legs and his flat chest, I do not know.” Kromer’s desire to distance himself from Mrs. Carter paradoxically calls attention to his own outsider status, odd in a narrative that theoretically offers an insider’s view of being down-and-out. Rarely at a loss for the right slang to describe his adventures, Kromer here fumbles to correctly categorize Mrs. Carter, identifying her with male pronouns consistently until he is confronted by a local:

“Did you make her?” This skinny stiff next to me at the counter says.

“Make who?”

“Mrs. Carter,” he says. “I see you talkin’ to her in the park.”

When Kromer asks about Mrs. Carter’s roommate, the correction is even more palpable:

“He queer, too,” I say.

“Sure, she’s queer,” he says, “but you will not have a chance with her.”

In the blue paper insert for the British edition, the publishers dither about where the line may be drawn about which “horrors to which helpless vagrants are exposed” can be represented in print. Kromer’s narrative in the chapter, though, insists that he and Mrs. Carter are playing a game in which he is the victor, the one on the make. It is perhaps this, more than any other element of the chapter, that opens it up to censure and moralizing. Unable to subordinate himself to Mrs. Carter, Kromer steps out of the role of helpless vagrant; after all, “A guy has got to eat, and what is more, he has got to flop.”

Kromer’s book is just one example of how the items in this collection will spark new conversations about life on the skids in the twentieth century.