Regular readers will know of our fondness for the English Gothic novel, and our pride in the recent bequest of the Maurice Lévy Collection of French Gothic (described in two recent blog posts). We have now acquired a key edition—the rare first edition in French (Lausanne, 1787) of William Beckford’s Vathek—which nicely links the Lévy Collection with its progenitor, the unparalleled Sadleir-Black Gothic Novel Collection housed under Grounds in the Small Special Collections Library.

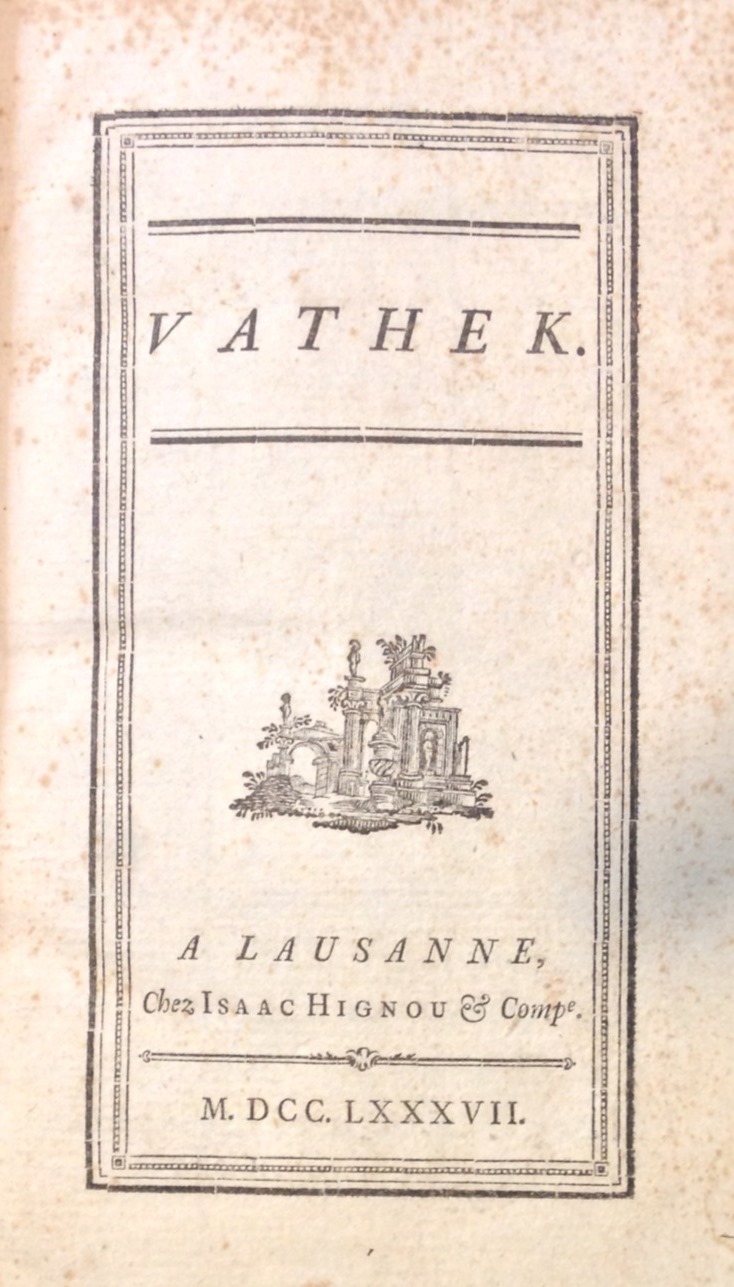

Title page of the second published edition (and the first printing of the original French text) of William Beckford’s Vathek. Lausanne: Isaac Hignou, 1787. (PR4091 .V39 1787)

One of the earliest, and now one of the most widely read English Gothic novels, Vathek has a complicated textual history. In a very important sense it is not even an English novel, for when Beckford composed the text in 1782, he did so in French! Indeed, Beckford never prepared an English translation of his best known work. Rather, most readers have encountered Vathek in the English translation (or in translations of this translation) prepared by the Rev. Samuel Henley, sometime professor at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia.

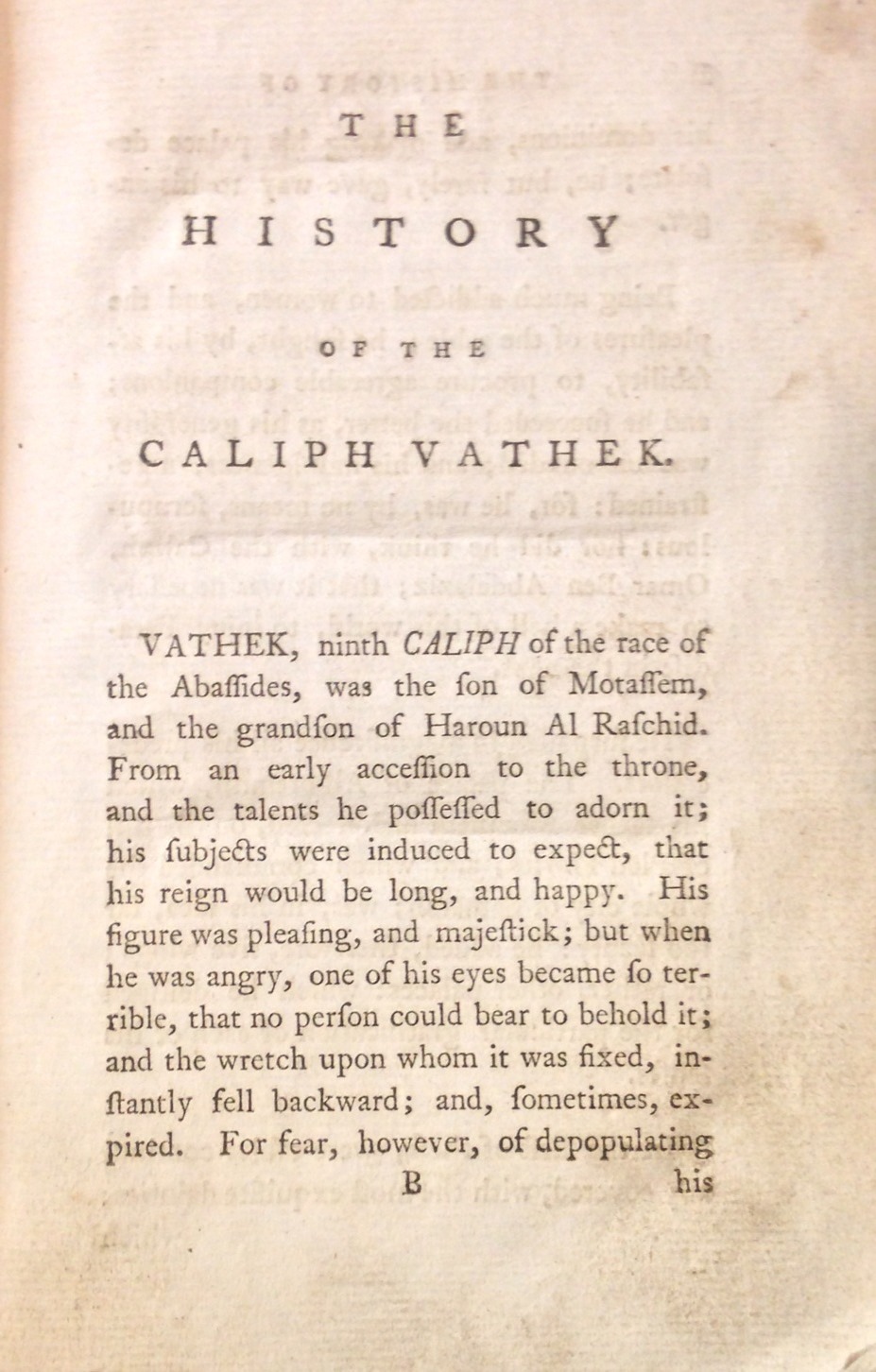

The first page of the Rev. Samuel Henley’s translation, from the first edition of Vathek, published under the title, An Arabian Tale. London: J. Johnson, 1786. (PR 4091 .V4 1786)

Born in 1745 in Devon, Henley was recruited in 1770 for the faculty of William and Mary, where he taught moral philosophy. Popular with his students—who included James Madison and James Monroe—Henley also formed strong friendships with prominent Virginians such as George Wythe and Thomas Jefferson. The looming clouds of war prompted Henley’s return to England in 1775, where he accepted a teaching position at Harrow School. By 1783 Henley had entered the intellectual circle of William Beckford, who entrusted him with translating the as yet unpublished Vathek into English. But Beckford, distracted in part by a scandal which necessitated an extended sojourn in Switzerland, insisted that Henley’s version remain unpublished until he saw fit to publish the original French text.

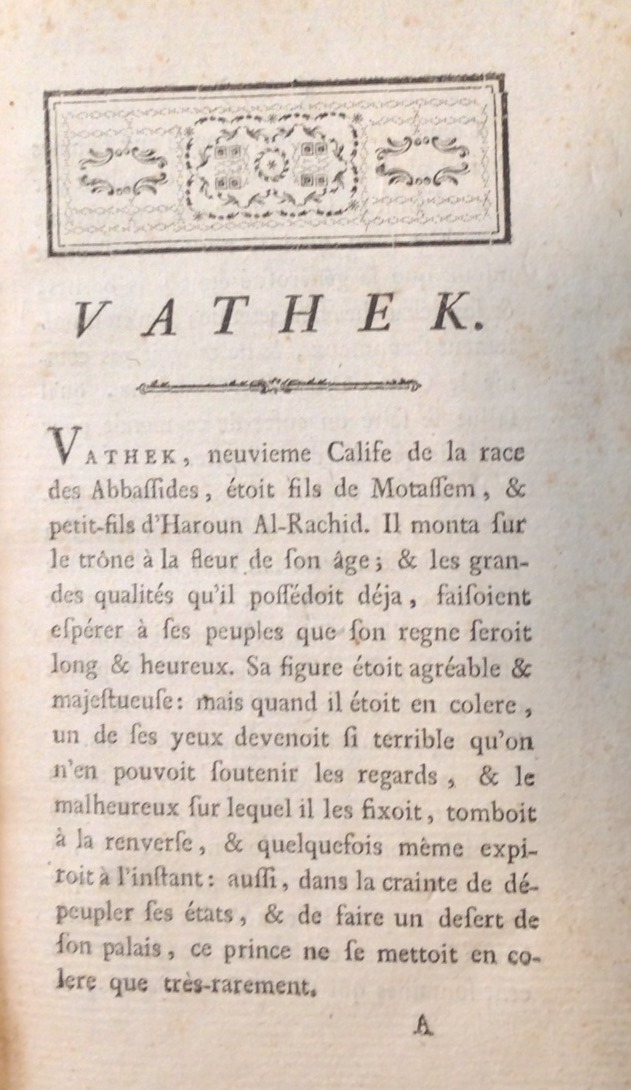

And for comparison, the first page of Beckford’s French text, as it appeared in the Lausanne, 1787 edition.

Disobeying Beckford’s wishes, Henley instead sent his translation to the press. Published in London in 1786 as An Arabian tale, Henley not only concealed Beckford’s authorship but pretended that the work was translated from an “Arabick” source. When the news reached Beckford in Lausanne, he was furious. Placing the original manuscript in the hands of a Swiss friend, Beckford directed that his French be corrected where necessary and the text rushed into print. The latter request was easier to meet than the former: the novel was published early in 1787 at Lausanne as Vathek, but with Beckford’s faulty French little improved. Today the Lausanne edition is very rare and, because Beckford’s manuscript no longer survives, remains our closest witness to the text as originally written. In subsequent editions, Beckford continued to tinker with both the French text and Henley’s translation, creating an interesting challenge for the textual editor.

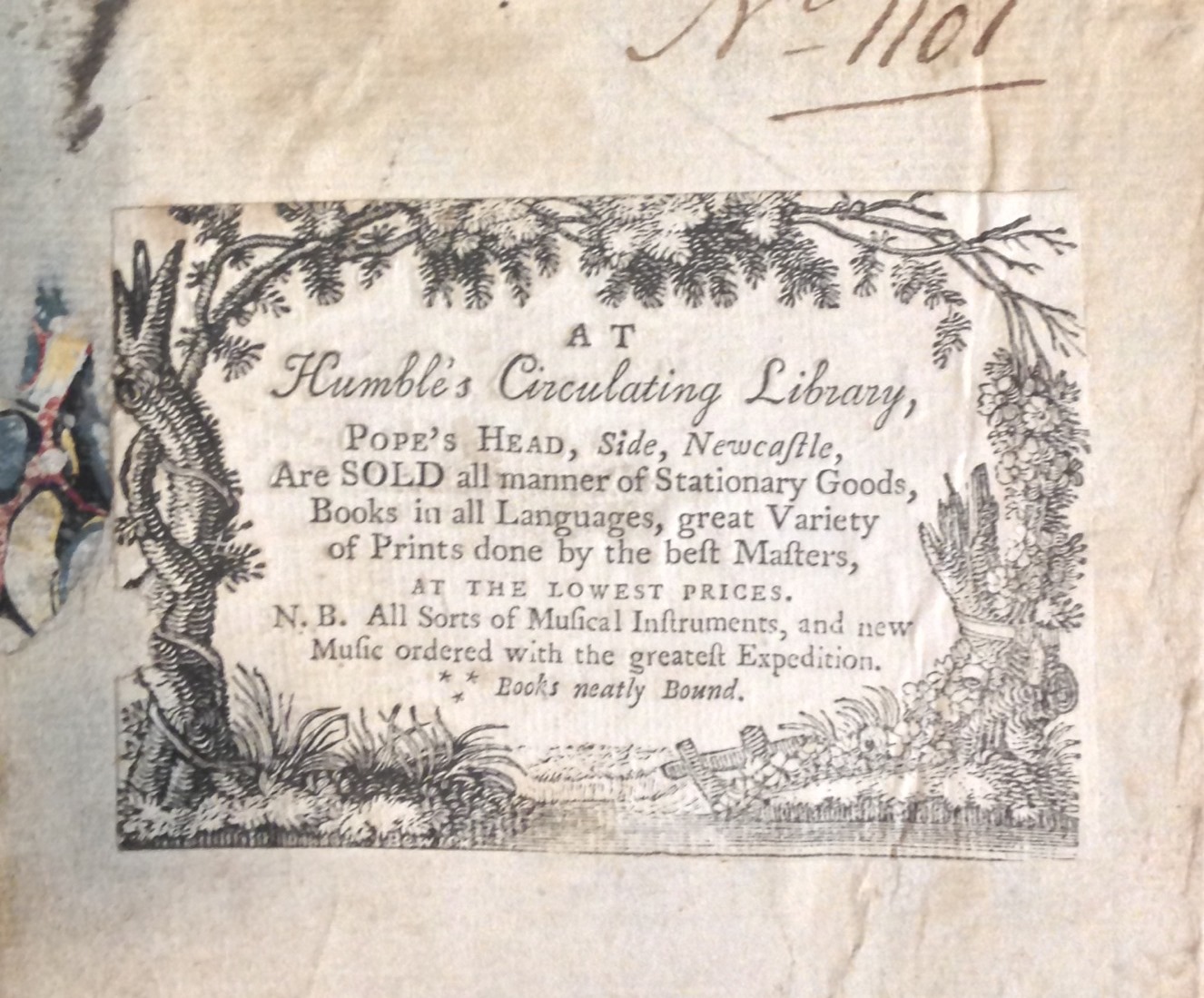

The Small Special Collections Library possesses two copies of the London, 1786 edition. One is in a fine binding with distinguished provenance. Despite its rather shabby appearance, the other copy is even more interesting, for it bears the contemporary wood-engraved label–by Thomas Bewick, no less!–of Humble’s Circulating Library in Newcastle.